Arsenault Raymond. Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

426 Freedom Riders

all the good news they could muster during the next three days. Tensions

related to a perceived power grab by the national staff reinforced the sense of

crisis as the convention’s 160 delegates considered a series of resolutions

crafted to deal with the legal and financial ramifications of direct action. At

several points during the weekend it appeared that the staff might lose con-

trol of the situation. In the end, however, Farmer’s growing stature as a move-

ment hero prevailed.

Moments after the conference’s closing on Monday, a beaming Farmer

told reporters that CORE was not only alive and well but ready to expand the

struggle for freedom. After confirming CORE’s plan to withdraw the Free-

dom Rider appeals and after urging all of the defendants to return to Missis-

sippi to serve the remainder of their sentences, he called for a series of new

nonviolent initiatives. “It would be easy for us to get bogged down in litiga-

tion,” he explained, “and that is just what the state of Mississippi would like

to see. We have resolved to resume direct nonviolent action instead.” Not

only would there be new Freedom Rides, but squads of “Freedom Dwellers”

would soon fan out across the country to combat racial discrimination in the

housing industry. “Negro motorcades” would be sent to housing develop-

ments to ensure that “open houses” were truly open; real estate offices refus-

ing to serve blacks could expect sit-ins; and developers who enforced restrictive

covenants would be picketed. At the same time, CORE’s existing campaign

against employment discrimination by chain stores would receive new em-

phasis. In particular, CORE planned to target the retail giant Sears Roebuck,

which generally restricted its black employees to menial positions. Finally, in

a gesture that did not go unnoticed at the Justice Department, Farmer also

announced an expansion of CORE’s involvement in voter registration.

4

Designed to restore momentum, Farmer’s press briefing reflected

CORE’s continuing commitment to direct action and the Freedom Rides,

but it remained to be seen whether the embattled organization could put any

of its ambitious plans into operation. Even within the movement there was

widespread skepticism about CORE’s capacity to sustain a broad program of

direct action; and back in Mississippi many local and state officials dismissed

Farmer’s declarations as empty bluster. Noting that five hundred dollars in

bail money would be returned to each Freedom Rider who decided to serve

out his or her sentence, one assistant city prosecutor claimed that CORE’s

decision to drop the appeals was a desperate gambit “to get their hands on

the appeal bond money.” In Jackson, CORE’s change in tactics was widely

interpreted as a sign of weakness and impending defeat. “Mississippians are

beginning to feel they have licked the ‘Freedom Rider’ movement,” an Asso-

ciated Press story in the Jackson Daily News reported on Wednesday, Sep-

tember 6. Quoting unnamed local observers, the story suggested that the

Freedom Riders’ “prolonged attack” on Mississippi had “backfired.” The

American public, one observer insisted, had concluded that outside agitators

Oh, Freedom 427

“were taking unfair advantage” of a state that had “bent over backward being

fair to them, within the framework of segregation.”

5

Farmer and other movement leaders were quick to dispute this assess-

ment of public opinion, but in the days following the CORE convention

they could not deny that the movement’s image was in need of restoration. If

the Freedom Riders’ association with Robert Williams and the Monroe fugi-

tives was not enough to worry about, there was also renewed violence in

southwestern Mississippi. When Bob Moses and Travis Britt accompanied

four local blacks to the Liberty courthouse on Tuesday morning, September

5, they were intercepted by an angry crowd of white protesters. While the

four applicants were inside trying to register, Britt was assaulted by an en-

raged white man who kept shouting “Why don’t you hit me, nigger?” Refus-

ing to fight back, the veteran Freedom Rider and NAG activist was nearly

unconscious after being slammed to the ground, but with Moses’s help he

managed to stagger to their car and escape serious injury.

Both Moses and Britt were safely back in McComb before nightfall, but

more movement-related violence occurred on Wednesday, this time in a

highly unlikely setting. When nonviolent leaders learned that a riot had bro-

ken out at the annual convention of the nation’s largest association of black

Baptists, some were convinced that a hex had been placed on the move-

ment. Meeting in Kansas City, Missouri, the leaders of the National Bap-

tist Convention, including Martin Luther King, allowed a tense September

6 plenary session to turn into a brawl that sent several delegates to the

hospital. One prominent minister, the Reverend A. G. Wright of Detroit,

suffered a fractured skull and a brain hemorrhage, and when Wright died two

days later King and the entire nonviolent movement shared the shame and

embarrassment.

6

As damaging as Wright’s death was for the overall image of the move-

ment, CORE had even more pressing concerns to address. On Tuesday, the

day before the brawl in Kansas City, two white Freedom Riders, Elizabeth

Adler and Peter Ackerberg, elected to go ahead with their appeals. Con-

victed and released on a fifteen-hundred-dollar bond, they were joined on

Wednesday morning by the Minnesota Freedom Rider Zev Aelony, who

became the fifth defendant to go to trial. Coming on the heels of Farmer’s

press conference, the three appeals called CORE’s influence into question.

To add to the confusion, the defendant scheduled for trial on Wednesday

afternoon—Alex Anderson, a thirty-three-year-old black Methodist minis-

ter from Nashville—tried to withdraw his appeal at the last minute but was

told he could not do so. Sustaining an objection by Jack Travis, Judge Moore

ruled that Mississippi law did not allow for the withdrawal of an appeal fol-

lowing arraignment. A defendant could change his plea, Moore later advised,

but dropping the appeal altogether was not an option. Although Jack Young

pointed out that several defendants had already done so, Moore refused to

alter his interpretation of state law.

428 Freedom Riders

Shocked by this sudden turn of events, Young soon turned to the only

viable option left open to him—counseling his clients to plead nolo conten-

dere. On Friday, Frank Ashford, a twenty-two-year-old black student from

Chicago, became the first Freedom Rider to enter such a plea, and Judge

Moore responded by assessing a two-hundred-dollar fine and a four-month

suspended sentence. Later in the day, Tom Armstrong, a nineteen-year-old

Tougaloo student, adopted a different strategy and entered a not guilty plea,

but after he was convicted by the jury, Moore pronounced a punitive sen-

tence, including release on a fifteen-hundred-dollar bond. This sent a clear

signal to financially strapped CORE officials, who advised Young and other

movement attorneys to encourage their clients to follow Ashford’s lead. Al-

though worthless as a basis for appeal to a higher court, a mass of no contest

pleas would save CORE and the Freedom Riders a great deal of money over

the coming weeks.

7

While CORE leaders were mulling over their limited options, the struggle

over voting rights in Pike and surrounding counties took a new turn. On

Thursday, the day after Judge Moore’s ruling, John Hardy’s attempt to reg-

ister two black voters at the Walthall County courthouse in Tylertown led to

a beating at the hands of the county registrar, John Wood. Accompanied by

MacArthur Cotton, a Tougaloo student who had been helping him run a

voter registration school for Walthall’s black farmers, Hardy stood quietly

outside Wood’s office until it became clear that neither of the applicants

would be allowed to register. After inquiring about the situation, the Nash-

ville SNCC activist caught the full fury of Wood’s ire. “What right do you

have coming down here messing in these people’s business? Why don’t you

go back where you came from?” the registrar asked, before pulling a pistol

out of a drawer and pointing it at Hardy. Frightened, Hardy turned to leave

but was struck on the back of the head with the pistol butt before he could

get out the door. Staggering into the street, he soon encountered Sheriff Ed

Kraft, who all but laughed at his request that the registrar be arrested for

assault. Instead, Sheriff Kraft hauled Hardy off to the Tylertown jail, charg-

ing him with resisting arrest and inciting a riot. After several hours of inter-

rogation by local prosecuting attorneys, Hardy was told that he was being

transferred to the Magnolia jail for his “own protection”; and by nine o’clock

that evening he found himself in the same cell block that had housed Bob

Moses three weeks earlier.

After Hardy was released on bond the next morning, Moses phoned John

Doar to see if the Justice Department was willing to follow through with the

promise to protect the rights of voter registration activists. Following his call

to Doar from the Magnolia jail in mid-August, Moses had sensed that the

man who witnessed the attack on the Freedom Riders in Montgomery was a

cut above the normal Justice Department bureaucrat, but he was still sur-

prised when Doar actually dispatched two staff attorneys to Mississippi to

investigate Hardy’s confrontation with John Wood. Even more surprising

Oh, Freedom 429

was the Justice Department’s effort to block Hardy’s prosecution by Missis-

sippi authorities. With Burke Marshall’s approval, Doar sought a temporary

restraining order that would delay a scheduled September 22 trial. Citing a

provision of the 1957 Civil Rights Act prohibiting intimidation of voters on

racial grounds, Justice Department attorneys pleaded their case before Dis-

trict Judge Cox but came away with nothing but a judicial scolding from the

segregationist stalwart. Undaunted, Doar immediately flew to Montgomery

to make a personal appeal to Circuit Judge Richard Rives, who agreed to

convene a three-judge Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals panel. When the panel

met in Montgomery later in the month, Marshall himself argued the

government’s case in U.S. v. Wood, and by a vote of two to one the court

granted his request to overrule Cox, setting an important legal precedent for

federal intervention in voting rights cases.

Although Marshall’s successful appeal to the Fifth Circuit was good news

for Hardy, Justice Department leaders had no intention of asserting such

authority when issues other than voting rights were involved. Within the

Civil Rights Division, there was considerable sympathy and growing admira-

tion for the Freedom Riders and other student activists challenging the sta-

tus quo in the Deep South, but in the political context of 1961 these sentiments

did not lead to broad-based or sustained legal intervention. Beginning with

the first arrests in Jackson in late May, the intimidation of Freedom Riders

by state and local officials had drawn little public comment from federal offi-

cials. And, despite the civil rights rhetoric that animated the attorney general’s

ICC petition, there was no indication that the events of the late summer had

altered the administration’s essentially neutral position on the prosecution of

nonviolent dissenters. Detecting little or no political pressure to intervene

on behalf of the Freedom Riders and judging public opinion to be sharply

divided on the issue, administration leaders from the president on down were

unwilling to undertake risky or radical initiatives that might endanger exist-

ing political arrangements.

8

Aside from a few maverick politicians and left-leaning commentators,

those who spoke out most forcefully for the right to agitate were either the

Freedom Riders themselves, student activists on college campuses, or liberal

religious leaders. During the late summer and early fall of 1961, recent vet-

erans of the Freedom Rides delivered lectures and testimonials at scores of

churches and colleges across the nation. Virtually all of the original CORE

Riders participated in this makeshift speakers bureau, and Ed Blankenheim,

Hank Thomas, and Ben Cox—all of whom had joined the CORE staff—

were especially active as recruiters and fund-raisers. Almost all of this activity

took place in carefully selected venues where a sympathetic audience was

guaranteed, namely college lecture halls and chapels. While the vast major-

ity of students and faculty at predominantly white institutions Sremained too

conservative to embrace the Freedom Rides, movement lecturers attracted

significant attention and support on campuses from Cornell to UCLA. Even

430 Freedom Riders

in the South there were signs that at least some white students harbored

sympathy for the Riders. One notable expression of support surfaced on Sep-

tember 8, when several dozen students gathered at the Tennessee state capi-

tol in Nashville to protest the expulsion of fourteen Freedom Riders from

Tennessee State. While an interracial group of twenty-five picketed outside

the capitol, eleven others, including John Lewis, formed a double line in

front of Governor Buford Ellington’s office. Although Ellington managed to

scurry out a side door without confronting the protesters, the boldness of the

students’ action did not go unnoticed in a nation unaccustomed to such as-

sertive behavior. The sit-ins and the Freedom Rides had involved private

businesses and a few public terminals, but now the student invasion had spread

to a seat of state government.

9

Most of the students involved in the Tennessee capitol protest were black,

and much of the student movement resided on black campuses in the South.

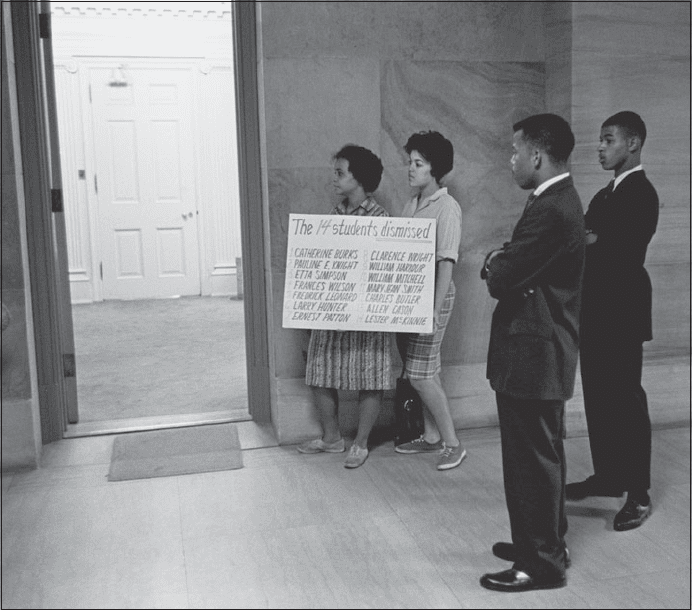

John Lewis (second from right) and other student activists stand at the entrance to

Tennessee governor Buford Ellington’s office to protest the expulsion of fourteen

Tennessee State University Freedom Riders, September 8, 1961. (Courtesy of

Nashville Tennessean)

Oh, Freedom 431

As Martin Luther King pointed out in a timely essay published in the New

York Times Magazine on September 10, the new contrasting symbols of the

civil rights struggle were the black student activist—“college-bred, Ivy League-

clad, youthful, articulate and resolute”—and the segregationist “hoodlum

stomping the bleeding face of a Freedom Rider.” Quoting the novelist Victor

Hugo’s assertion that “there is no greater power on earth than an idea whose

time has come,” King credited the black student vanguard with delivering

the message that “the time for freedom for the Negro has come.” “The young

Negro is not in revolt, as some have suggested, against a single pattern of

timid, fumbling, conservative leadership,” King insisted. “Nor is his conduct

to be explained in terms of youth’s excesses. He is carrying forward a revolu-

tionary destiny of a whole people consciously and deliberately. Hence the

extraordinary willingness to fill the jails as if they were honors classes and the

boldness to absorb brutality, even to the point of death, and remain nonvio-

lent.” While acknowledging that “not long ago the Negro collegian imitated

the white collegian,” he proclaimed: “Today the imitation has ceased. The

Negro collegian now initiates. Groping for unique forms of protest, he cre-

ated the sit-ins and Freedom Rides. Overnight his white fellow students be-

gan to imitate him.”

Such claims were more than enough to set most American parents on

edge, but King went on to expose the international roots of student activism.

“Many of the students, when pressed to express their inner feelings, identify

themselves with students in Africa, Asia, and South America,” he reported.

“The liberation struggle in Africa has been the greatest single international

influence on American Negro students. Frequently I hear them say that if

their African brothers can break the bonds of colonialism, surely the Ameri-

can Negro can break Jim Crow.” The students, King warned, were “not after

‘mere tokens’ of integration.” “Theirs is a revolt against the whole system of

Jim Crow,” he declared, “and they are prepared to sit-in, kneel-in, wade-in

and stand-in until every waiting room, rest room, theatre and other facility

throughout the nation that is supposedly open to the public is in fact open to

Negroes, Mexicans, Indians, Jews or what-have-you. Theirs is a total com-

mitment to this goal of equality and dignity. And for this achievement they

are prepared to pay the costs—whatever they are—in suffering and hardship

as long as may be necessary.”

King expressed the hope that the students’ spirit of commitment and

sacrifice would soon spread to other segments of the American population.

“These students are not struggling for themselves alone,” he reminded his

readers. “They are seeking to save the soul of America. They are taking our

whole nation back to those great wells of democracy which were dug deep by

the Founding Fathers in the formulation of the Constitution and the Declara-

tion of Independence. In sitting down at the lunch counters, they are in real-

ity standing up for the best in the American dream.” Predicting that “one day

historians will record this student movement as one of the most significant

432 Freedom Riders

epics of our heritage,” he asked plaintively if it made any sense for the rest of

the nation to “sit by as spectators when the social unrest seethes.” Since “most

of us recognize that the Jim Crow system is doomed . . . ,” he reasoned, “would

it not be the wise and human thing to abolish the system surely and swiftly?

This would not be difficult, if our national Government would exercise its full

powers to enforce Federal laws and court decisions and do so on a scale com-

mensurate with the problems and with an unmistakable decisiveness.”

10

DESIGNED TO PRICK THE CONSCIENCE of the American intellectual and politi-

cal elite, King’s essay appeared at a critical moment in the Freedom Rider

saga. Despite the essay’s declarative title—“The Time for Freedom Has

Come”—in reality the timing of freedom’s arrival in the Jim Crow South was

still very much in doubt. To bring the Freedom Rides to a successful and

timely conclusion, movement leaders would need every influential ally they

could muster, especially in the legal arena. On Monday, September 11, the

arraignment of seventy-eight additional Freedom Rider defendants in Jack-

son intensified the legal and financial pressure bearing down on CORE. Af-

ter each defendant pleaded not guilty, the Hinds County court scheduled

appellate trials for the spring of 1962, ensuring that the legal struggle in

Mississippi would continue for at least nine more months. The movement’s

prospects for a quick legal victory were no more promising in Alabama, where

white officials announced on Tuesday that the U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of

Appeals had upheld Judge Frank Johnson’s ruling that William Sloane Cof-

fin, Wyatt Tee Walker, Fred Shuttlesworth, Ralph Abernathy, and six other

Freedom Riders must stand trial on the breach-of-peace charges filed on

May 25. This and other recent developments drew cheers that evening at a

raucous White Citizens’ Council rally in Montgomery. As more than 800 WCC

members looked on, the special guest speaker, Governor Ross Barnett, re-

ported that the “ruthless actions” of the Freedom Riders, the NAACP, and

meddlers such as Chief Justice Earl Warren had backfired. Outside agitators

were on the run, Barnett declared, and even in the North the integrationist

cause was losing ground. Back in Jackson, according to the governor, the Free-

dom Riders were finally learning the full meaning of Mississippi justice.

11

On Wednesday morning Barnett’s words took on added weight when

Jim Bevel went on trial for contributing to the delinquency of a minor.

Charged with enticing four local high school students to demonstrate in sup-

port of the Freedom Rides, Bevel refused Judge Russel Moore’s offer of a

light sentence in exchange for a no-contest plea. Acting as his own counsel,

the twenty-four-year-old minister was eloquent in defending the young stu-

dents’ right to bear witness against the evil of Jim Crow, but not even Bevel,

the most mystical of the Nashville Freedom Riders, could make any headway

against the flow of racial tradition. Following a swift conviction, Moore is-

sued the maximum sentence of two thousand dollars in fines and six months

Oh, Freedom 433

in jail. Bevel, who for the time being chose not to appeal, was behind bars by

early afternoon. And he was not alone. Earlier in the day, while Bevel was

standing trial, the Jackson police had arrested fifteen new Freedom Riders at

the Trailways terminal.

12

All of those arrested—twelve whites and three blacks—were Episcopal

priests affiliated with the Episcopal Society for Cultural and Racial Unity, an

Atlanta-based group of racially liberal clergymen and lay leaders. Led by the

Reverend John B. Morris of Atlanta, they were part of a twenty-eight-member

“prayer pilgrimage” that had originated in New Orleans on Tuesday. Travel-

ing to Jackson via Vicksburg by chartered bus, all twenty-eight spent Tues-

day night at Tougaloo College, to the consternation of the Reverend John

Allin, the bishop of the Mississippi Episcopal Diocese. Informed that the

pilgrims were headed for Detroit, where the sixtieth General Convention of

the Episcopal Church was scheduled to open on Thursday, Allin urged them

to move on in “a quiet and orderly manner” without disrupting the social

peace of Mississippi. While he saw “no value” in the strategy of nonviolent

resistance, fifteen of the priests felt otherwise. Piling into three black taxi-

cabs, the interracial band of brothers rode to the Trailways terminal with the

intention of desegregating the white waiting room. Intercepted by Captain

Ray and two other policemen, the priests became the thirty-seventh group of

Freedom Riders arrested in Jackson. Since six weeks had passed since the last

round of arrests on July 31, the priests’ arrival at the city jail caused quite a

stir, especially after the police and the press discovered that one of the ar-

rested Freedom Riders was Robert L. Pierson, the thirty-five-year-old son-

in-law of Nelson Rockefeller, the liberal Republican governor of New York.

While Pierson and his colleagues were being processed at the jail, the

other participants in the pilgrimage sent a telegram to Robert Kennedy. “In

view of your request to American clergymen to exert leadership in these ar-

eas,” the message read, “we urge you immediately to apply your influence to

resolve problems of interstate travel for Americans.” The clergymen also

“called upon the nation to say special prayers for their fifteen colleagues and

the cause of integration daily at 7 a.m., noon, and 7 p.m.” Speaking for the

entire group, the Reverend Malcolm Boyd, an Episcopal chaplain at Wayne

State University in Detroit, vowed that the pilgrimage would continue; and

on Thursday he and five other priests made good on the promise by travel-

ing to Sewanee, Tennessee, home of the partially desegregated University of

the South. While the Episcopal seminary at the University was racially inte-

grated, the staunchly traditional undergraduate student body remained all

white. Encouraged by the interracialism of the nearby Highlander Folk

School, local seminarians had been pressing for a full desegregation of the

campus for several years, but university and church officials had refused to

confront the issue, including a strict color bar at a popular on-campus restau-

rant leased to a local segregationist. As soon as Boyd and the other pilgrims

arrived on campus and discovered that the restaurant remained segregated,

434 Freedom Riders

he announced plans for a sit-in and a hunger strike. By Friday morning, how-

ever, Boyd had received assurances from church and campus officials that all

of the university’s facilities would be desegregated in the near future. After

the presiding Episcopal bishop of the United States, the Right Reverend

Arthur C. Lichtenberger, issued a strong public statement endorsing the

prayer pilgrimage and condemning racial discrimination, Boyd and his col-

leagues canceled the planned protests and departed for the convention in

Detroit.

Several other Episcopal leaders—including the bishop of Rhode Island,

who wired five hundred dollars of bail money to one of the jailed priests—

spoke out in defense of the prayer pilgrimage. But such support had no dis-

cernible effect on the situation in Jackson. On Friday, after two nights in jail,

the fifteen defendants went on trial in the municipal court of Judge James

Spencer. A lifelong Episcopalian, Spencer felt an obligation to scold the way-

ward priests on religious as well as legal grounds. Unmoved by Carl Rachlin’s

impassioned defense of the priests’ actions, Spencer explained his special re-

sponsibility to discipline the defendants. “As a judge of Episcopal faith,” he

declared, “I find my position especially grievous and as I read the articles of

religion of my faith and what I reasoned to be their faith, I find in Article 37

. . . the short paragraph which says—‘and we hold it to be the duty of all men

who are professors of the Gospel to pay respectful obedience to the civil

authority.’ I find my duty clear as a judge. I believe these definitely have

violated the laws of the State of Mississippi as well as those of the Episcopal

law of the articles of religion as I read them.” Accordingly, he sentenced each

defendant to a two-hundred-dollar fine and four months in jail.

The next morning the press reported that the fifteen clergymen were

back in the city jail praying “for the segregationists whose policies had led to

their imprisonment.” In Detroit, where the national Episcopal convention

was still in session, and in many other Northern cities, there were signs of

sympathy for the jailed priests. Locally, any feelings of remorse were tem-

pered by a wire service story detailing a pretrial conversation between Mayor

Allen Thompson and the Reverend Lee Belford of New York. According to

Thompson, Belford told him that the prayer pilgrimage “would have been

worth it” even if it had led to violence. “Our church has a history of martyr-

dom,” Belford proudly explained.

13

The wide philosophical gulf between white Christian segregationists and

social gospel activists such as Belford became increasingly clear in the fall of

1961, as segregationist officials demonstrated their willingness to mete out

harsh punishment to clergymen who violated the South’s racial mores. On

September 15, the same day that the fifteen priests faced Judge Spencer in

Jackson, the Reverend William Sloane Coffin and nine other ministerial Free-

dom Riders charged with breaching the peace were assessed hundred-dollar

fines and sentenced to jail terms ranging from ten to fifteen days by Mont-

gomery County Judge Alex Marks. The two local defendants, Ralph Abernathy

Oh, Freedom 435

and Bernard Lee, received ten-day sentences, but all the others, including

Shuttlesworth, received fifteen days. An eleventh defendant, Wyatt Tee Walker,

was actually acquitted on the breach-of-peace charge, but conviction on a

related charge of unlawful assembly resulted in a ninety-day sentence. Ex-

plaining the severity of Walker’s sentence, Judge Marks reasoned that the

SCLC executive director’s role as a liaison to the press made him especially

dangerous. “There would have been very little trouble in Montgomery if

there hadn’t been so much publicity,” Marks insisted. All of the defendants,

including Walker, filed immediate appeals and accepted bail, but as they left

the courthouse they could not help wondering how far Alabama officials were

willing to go in their effort to ensnare the movement in a tangle of legal

prosecutions.

14

For Shuttlesworth, who had faced the hard edge of the Alabama legal

system more times than he could count, the question was particularly trou-

bling. A year earlier almost to the day, W. W. Rayburn, a juvenile court

judge in Gadsden, had placed Shuttlesworth’s three teenaged children—

Patricia, Ricky, and Fred Jr.—on indefinite probation after they occupied

the front seats on a Greyhound bus traveling from Chattanooga to Birming-

ham. Returning from an interracial nonviolence workshop at Highlander,

they tried to act out the principles that they had learned but were thwarted

by a vigilant bus driver and a police officer who later claimed that he arrested

them “for their own protection.” After hearing someone in a crowd outside

the bus yell, “Get those damned niggers off the bus, or we’ll throw them

off!” the officer carted the children off to jail, where they encountered more

threats from their guards. By the time Shuttlesworth arrived to retrieve his

children, Fred Jr. had been roughed up by a guard who put him in a choke

hold, and all three had been warned that their “cotton-pickin’ nigger” father

was unwelcome in Gadsden. After several hours of tense negotiation,

Shuttlesworth managed to free his children, and three days later Judge

Rayburn put them on probation. But the mean-spirited prosecution in

Gadsden elicited cries of outrage from the NAACP and SCLC, both of which

called for a Justice Department investigation. When the brief FBI investiga-

tion that followed went nowhere, Shuttlesworth filed a $9 million damage

suit in federal court alleging that the Southeastern Greyhound driver had

provoked an incident leading to false arrest and imprisonment. Originally

filed in Atlanta, the suit was eventually transferred to the U.S. District Court

in Birmingham, where it was still pending in September 1961.

15

Shuttlesworth’s effort to extract justice from the federal courts suggested

a measure of faith in American democracy. For more than a decade the Bir-

mingham minister had served as a model of assertive citizenship—a black

man undeterred by bombs, beatings, and legal harassment. Encouraged by

the Brown decision and the promise of a Second Reconstruction, he preached

and practiced a gospel of rising expectations for black Americans. During the

first eight months of the Kennedy presidency, the expansive rhetoric of the