Boggs S. Principles of Sedimentology and Stratigraphy

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

276

Chapter 8 I Continental (Terrestrial) Environments

8.5 GLACIAL SYSTEMS

Introduction

I have placed glacial systems last in this discussion of continental environments

because the glacial environment, in a broad sense, is a composite environment

that includes fluvial, eolian, and lacustrine environments. It may also include

parts of the shallow-marine environment. Glacial deposits make up only a rela

tively minor part of the rock record as a whole, although glaciation was locally im

portant at several times in the geologic past, particularly during the late

Precambrian, late Ordovician, Carboniferous/Permian, and Pleistocene (Eyles

and Eyles, 1992). Glaciers presently cover about 10 percent of Earth's surface,

mainly at high latitudes. They exist primarily as large ice masses on Antarctica

( �86 percent of the world's glaciated area) and Greenland ( � 11 percent of the

world's glaciated area) and as smaller masses on Iceland, Baffin Island, and Spits

bergen. Small mountain glaciers occur at high elevations in all latitudes of the

world. About SO percent of the world's fresh water is tied up in glacial ice, of

which most is in Antarctica (Hambrey, 1994, p. 31). By contrast to their present dis

tribution, ice sheets covered about 30 percent of Earth during maximum expan

sion of glaciers in the Pleistocene and extended into much lower latitudes and

elevations than those currently affected by continental glaciation.

The glacial environment is confined specifically to those areas where

more or less permanent accumulations of snow and ice exist. Such environ

ments are present in high latitudes at all elevations (continental glaciers) and

at low latitudes (mountain or valley glaciers) above the snowline-the eleva

tion above which snow does not melt in summer. Mountain glaciers form

above the snowline by accumulation of snow. They move downslope below

the snowline only if rates of accumulation of snow above the snowline exceed

rates of melting of ice below. The factors affecting glacier movement and the

mechanisms of ice flow (e.g., Martini et a!., 2001; Menzies, 1995) are not of pri

mary interest here. Our concerns are the sediment transport and depositional

processes associated with glacial movement and melting and the sediments

deposited by glaciers.

Environmental Setting

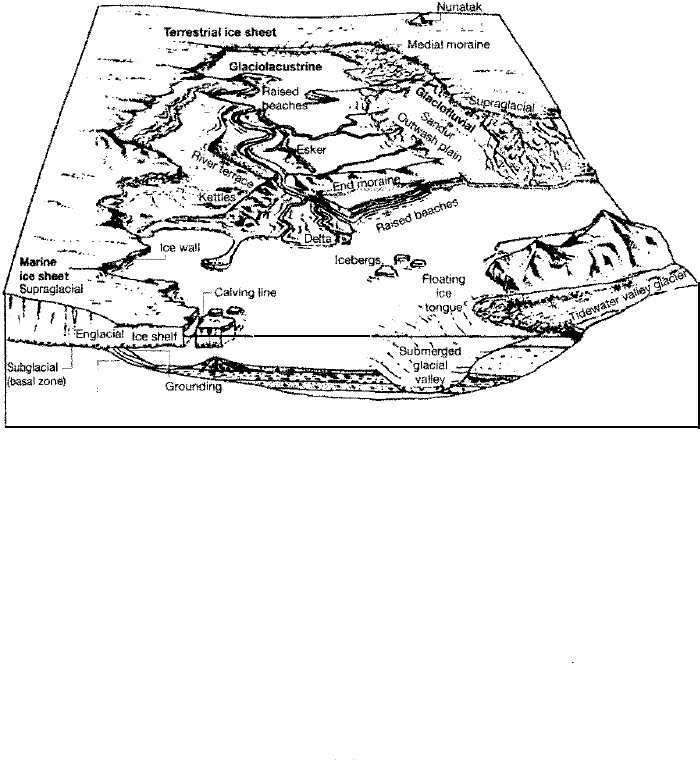

The glacial environment proper is defined as all those areas in direct contact

with glacial ice. It is divided into the following zones: (1) the basal or subglacial

zone, influenced by contact with the bed, (2) the supraglacial zone, which is

the upper surface of the glacier, (3) the ice-contact zone around the margin of

the glacier, and (4) the englacial zone within the glacier interior. Depositional

environments around the margins of the glacier are influenced by melting ice

but are not in direct contact with the ice. These environments make up the

proglacial environment, which includes glaciofluvial, glaciolacustrine, and

glaciomarine (where glaciers extend into the ocean) settings (Fig. 8.27). The

area extending beyond and overlapping the proglacial environment is the

periglacial environment.

The basal zone of a glacier is characterized by erosion and plucking of the

underlying bed. Debris removed by erosion is incorporated into the bed of the

glacier. This debris causes increased friction with the bed as the glacier moves and

thus aids in abrasion and erosion of the bed. The supraglacial and ice-contact

zones are zones of melting or ablation where englacial debris carried by the glaci

er accumulates as the glacier melts. The glaciofluvial environment is situated

downslope from the glacier front and is characterized by fluctuating meltwater

8.5 Glacial Systems

277

Subueous line

outwash

Giomari

Bedrock

ow and abundant coarse engladal debris that is available for fluvial transport.

e glaciofluvial environment is one of the characteristic environments in which

braided streams develop. Extensive outwash plains or aprons may also be present

along the margins of outwash glaciers. Lakes are very common proglacial fea

tures, created by ice damming or damming by glacially deposited sediments.

Meltwater streams draining into these lakes may create large coarse-grained

deltas along the lake edge, while finer sediment is carried outward in the lake by

sussion or as a density underow (Fig. 8.23). Glaciers that extend

out to sea

create an important environment of glaciomarine sedimentation where sediments

are

deposited close to shore by melting of the glacier in contact with the ocean or

farther out on the shelf or slope by melting of ice blocks, or icebergs.

The glacial environment may range in size from very small to very large.

Valley glaciers are relatively small ice masses confined whin valley walls of a

mountain. Piedmont glaciers are larger masses or sheets of ice formed at the base

of a mounta front where mountain glaciers have debouched from several val

leys and coalesced. Ice sheets, or continental glaciers, are huge sheets of ice that

spread over large continental areas or plateaus.

ansport and Deposition in Glacial Environments

Transport of sediment by ice is a kind of fluid-flow transport, although ice flows

very slowly as a high-viscosity, non-Newtonian pseudoplastic. Glaciers can ow

at

rates as high as 80 m per day during sporadic surges; however, typical flow

rates are on the order of centimeters per day (Martini et al., 2001, p. 50). In A Tramp

Abroad, Mark Tw ain describes his (fictitious) disappointment, after pitching camp

on an alpine glacier in expectation of a free ride down the valley, to find that the

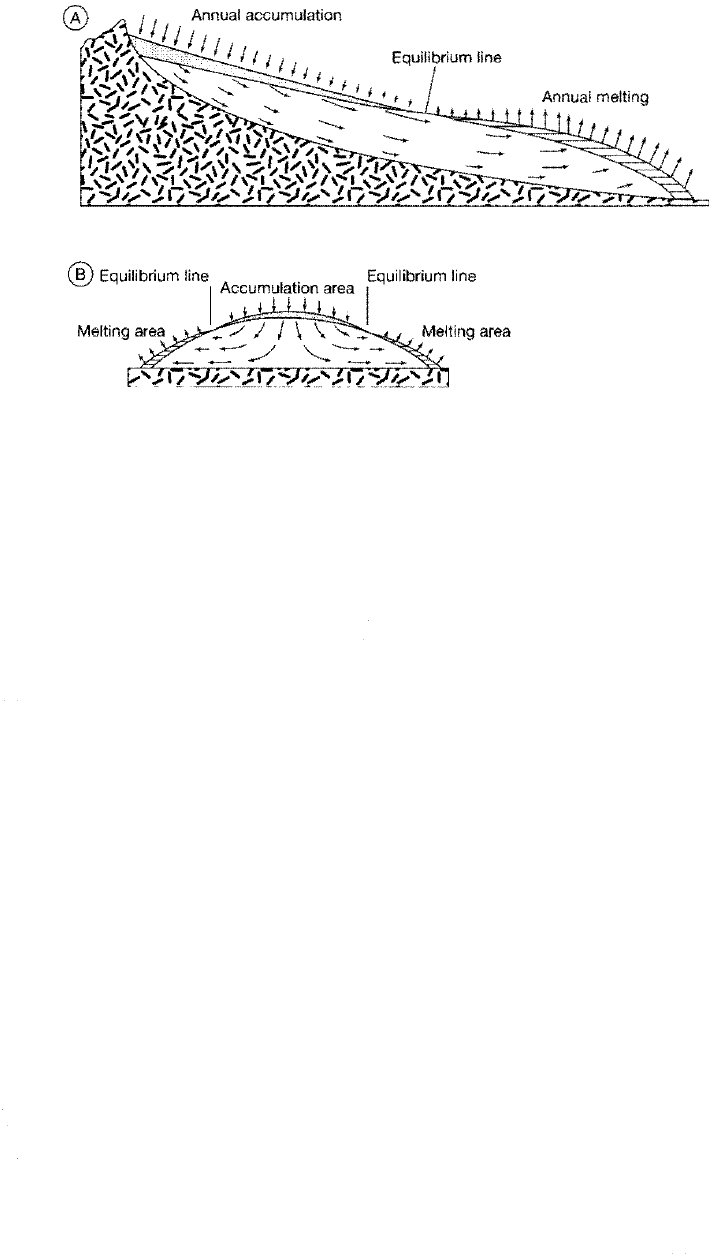

view from his camp remained the same day after day. Glaciers advance if the rate

of

accumulation of snow in the upper reaches (head) of the glacier exceeds the rate

of ablation (melting) of ice in the lower reaches (snout). The balance behveen ac

cumulation and melting is illustrated in Figure 8.28. Ice must !low internally

om the head of the glacier to replace that lost by melting at the snout. Flow of

e is laminar, and !low velocity is greatest near the top and center of the glacier.

Ve locity decreases toward the walls and tloor, alough not necessarily to zero.

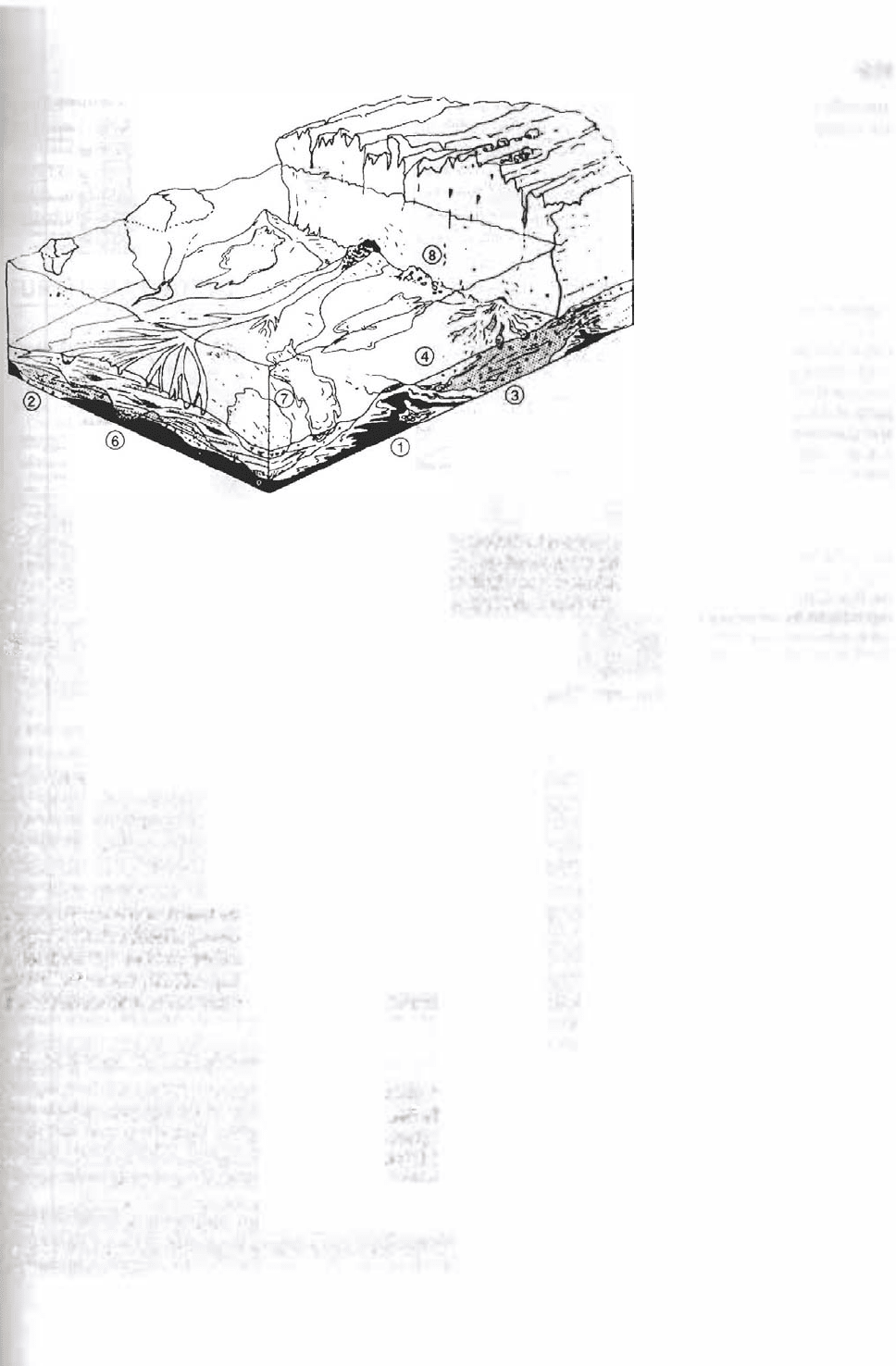

Figure 8.27

Glacial and associated

proglacial environments.

[After Edwards, M. B., 1986,

Glacial environments, in

Reading, H. G. (ed.), Sedi

mentary environments and

facies, 2nd ., Fig. 13.2, p.

448, reproduced by permis

sion of Elsevier Science Pub

lishers, Amsterdam.]

278

Chapter 8 I Continental e estrial) Environments

Fire 8.28

Diagrammatic two-dimensional illus

tration of the balance between glac

ier accumulation and melting and

the movement of ice within a glaci

er. A. Valley glacier. B. Ice sheet. [(A)

after Sharp, R. P. , 1988, living ice

Understanding glaciers and glacia

tion: Cambridge University Press,

Fig. 3.5, p. 58, and Fig. 3.6, p. 59,

reproduced by permission; (B) based

on

Sugden and john, 1976.]

Glaciers retreat if the rate of melting exceeds the rate of accumulation. They reach

a state of equilibrium, neither retreating nor advancing, when rates of melting and

accumulation are equal, although inteal movement of ice continues.

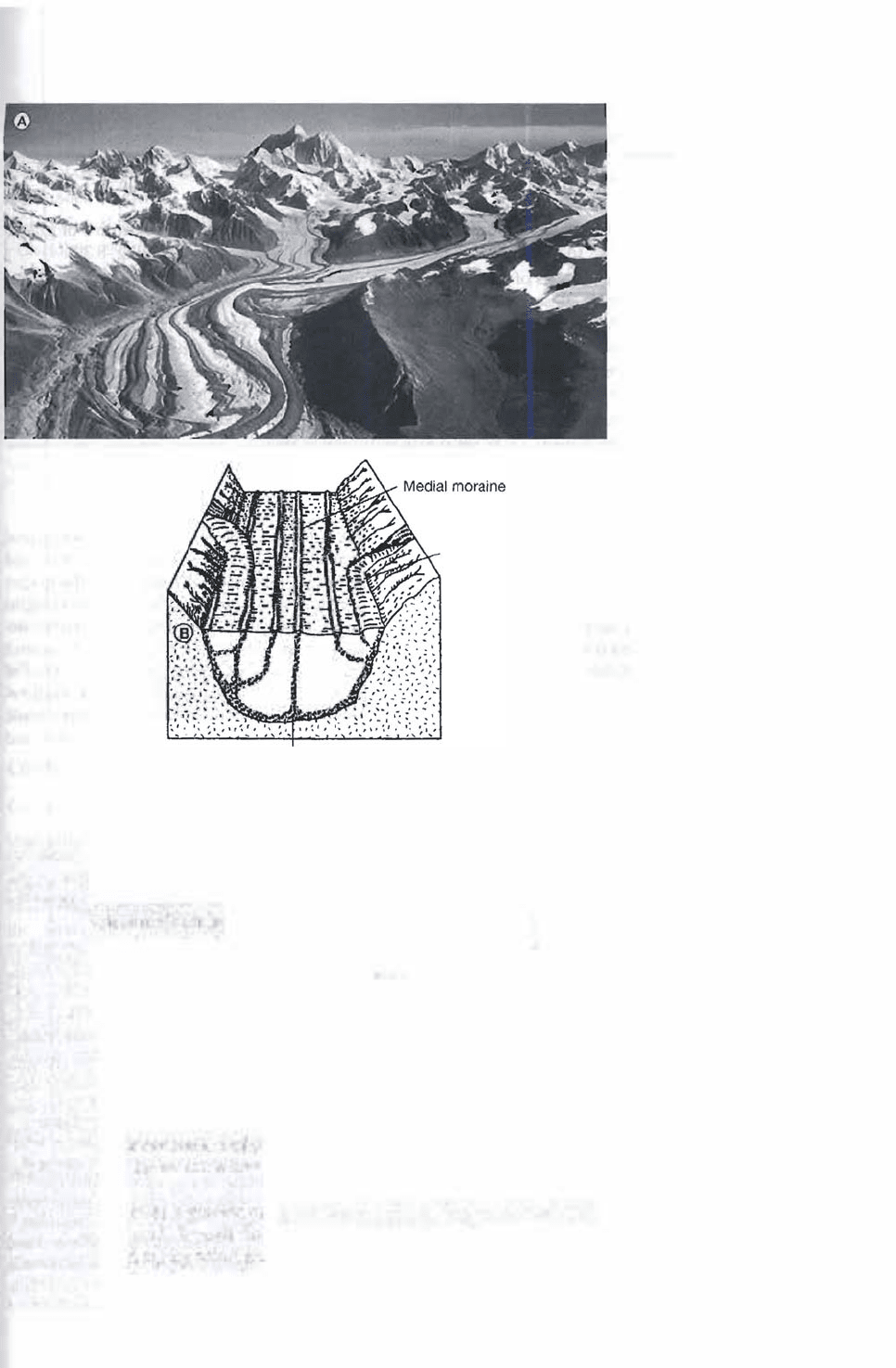

Sediment is entrained by glaciers by quarrying and abrasion by ice as the

glacier erodes its bed and by falling or sliding of material from the valley

walls. Some of this sediment is transported in contact with the valley walls

and floors and is responsible for much of the abrasion. Part of the remaining

load is carried on the upper surface of the glacier and part is carried within.

The internal load is derived either from the joining of ice streams from two or

more valleys or by the washing or falling of material from the surface into

crevasses (Fig. 8.29A). Much of the sediment transported by glaciers is carried

along the bottom and sides, as illustrated in Figure 8.298. The entrained sedi

ment load includes large and small blocks of rock as well as extremely fine

sediment, called rock flour, produced by grinding of the rock-studded glacier

base over bedrock. Thus, the glacier sediment load typically consists of an ex

tremely heterogeneous assortment of particles ranging from day-size grains to

meter-size boulders. Glaciers never become overloaded with debris to the

point that they become immobilized. As glacial ice melts, however, the sedi

ment load is dropped to form various kinds of glacial moraines. See Kirkbride

(1995) for details of sediment transport by glaciers.

As glaciers move downslope below the snowline, they eventually reach

an elevation where the rate of melting at the front of the glacier equals or ex

ceeds the rate of new snow accumulation above the snowline. If the rate of

melting approximately equals the rate of accumulation, the glacier achieves a

state of equilibrium in which it neither advances nor retreats. Within such an

equilibrium glacier, internal movement of ice continues to carry the rock load

along and supply rock debris to the melting snout of the glacier. This process

causes a ridge of unsorted sediment, called an end moraine or terminal

moraine, to accumulate in front of e glacier. Lateral moraines, or marginal

moraines, can accumulate from concentrations of debris carried along the

edges of the glacier where ice is in contact with the valley wall. Medial moraines

may form where the lateral moraines of two glaciers join (Fig. 8.29). When the

rate of melting at the snout of a glacier exceeds the rate of new snow accumula

tion above the snow line, the glacier retreats back up the valley. If a glacier re

treats steadily, it drops its load of rock debris as lateral moraines, medial

Lateral moraine

Ground moraine

8.5 Glacial Systems

279

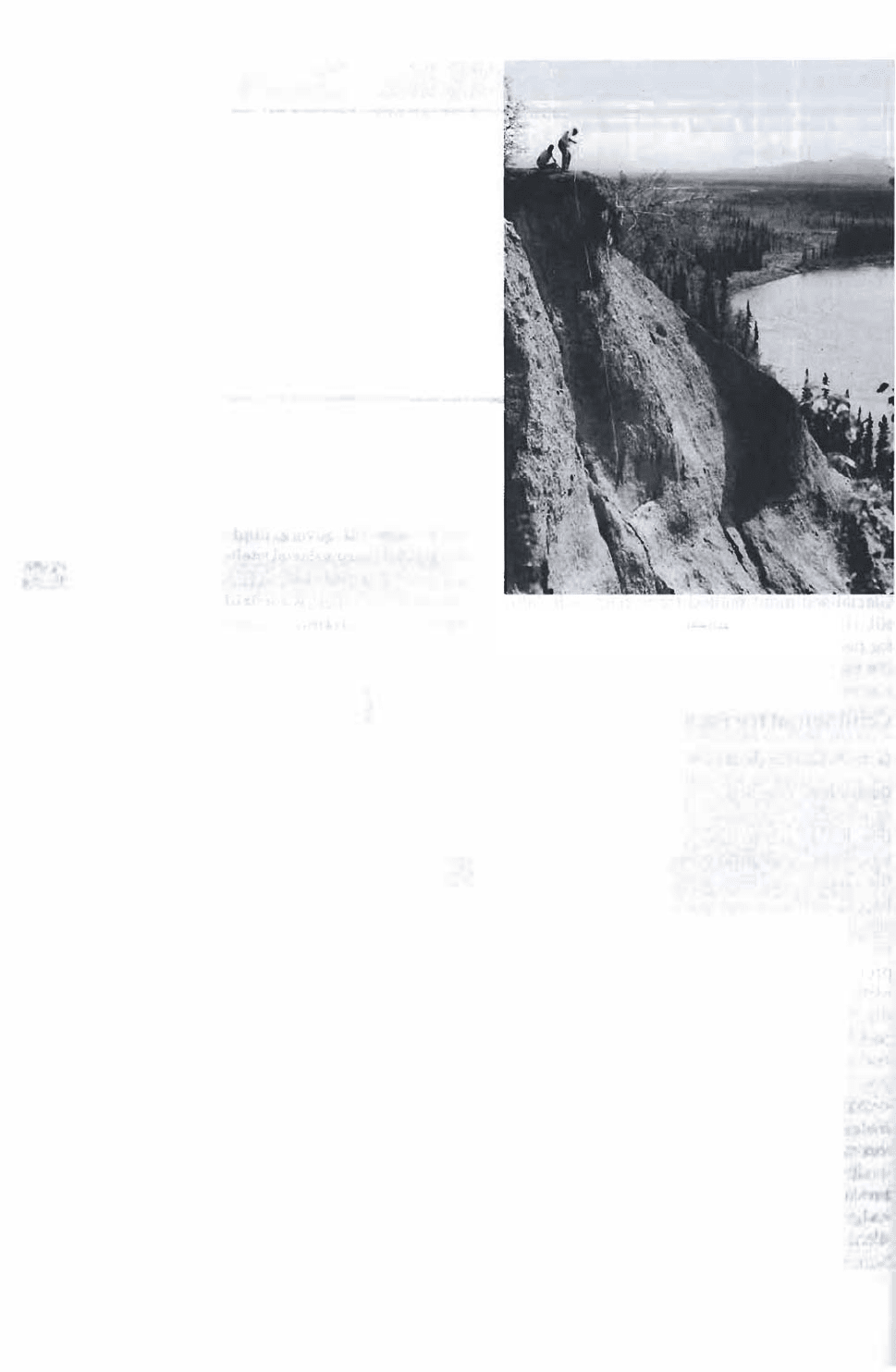

Figure 8.29

A. Susitna Glacier, eastern Alaska

Range, Alaska. The dark stripes are

sediments acquired by joining of ice

streams from the various valleys. [A.

Photograph by Austin Post, Ameri

can Geographic Society Collection

archived at the National Snow and

Ice Data Center, University of Col

orado, Boulder, and obtained from

the Internet at http:/ /-nsidc.col

orado.edu, downloaded Dec. 9,

1998]. B. Schematic representation

of sediment transport paths within

a glacier and the various kinds of

glacial moraines; compare with Fig.

A. [After Sharp, R. P., 1988, Living

ice-Understanding glaciers and

glaciation: Cambridge University

Press, Fig. 2.5, p. 30, reproduced

by permission.)

moraines, and a more or less evenly distributed sheet of ground moraine. If

the glacier retreats in pulses, it leaves a succession of end moraines, called

recessional moraines.

As glaciers melt on land, large quantities of water run along the margins, be

neath, and out from the front of the glacier to create a meltwater stream. Such

stams flow with high but variable discharge in response to seasonal and daily

temperature variations. Near the glacier front, the meltwater quickly becomes

choked with suspended sediment and loose bedload sand and gravel, leading to

for mation of branching and anastomosing braided-stream channels. Streams that

discharge into glacial lakes tend to build prograding delta systems into the lakes

with steeply inclined foresets that grade downward to gently inclined bottomset

beds (Edwards, 1986). Ve ry fine sediment discharged into the lake from streams

may be dispersed basin ward in suspension by wd-driven waves or currents. If a

large enough concentration f sediment is present in suspension to create a densi

ty difference in the water, a density underflow or turbidity current will result that

c carry sediment along the lake bottom into the middle of the basin. Strong

winds blowing over a glacier or an ice sheet pick up fine sand from exposed, dry

outwash plains and deposit the sand downwind in nearby areas as sand dunes.

Fine dust picked up by Wind can be kept in suspension and transported long dis

nces before being deposited as loess in the periglacial environment or as pelagic

sediment the ocean.

280

Chapter 8 I Continental errestrial) Environments

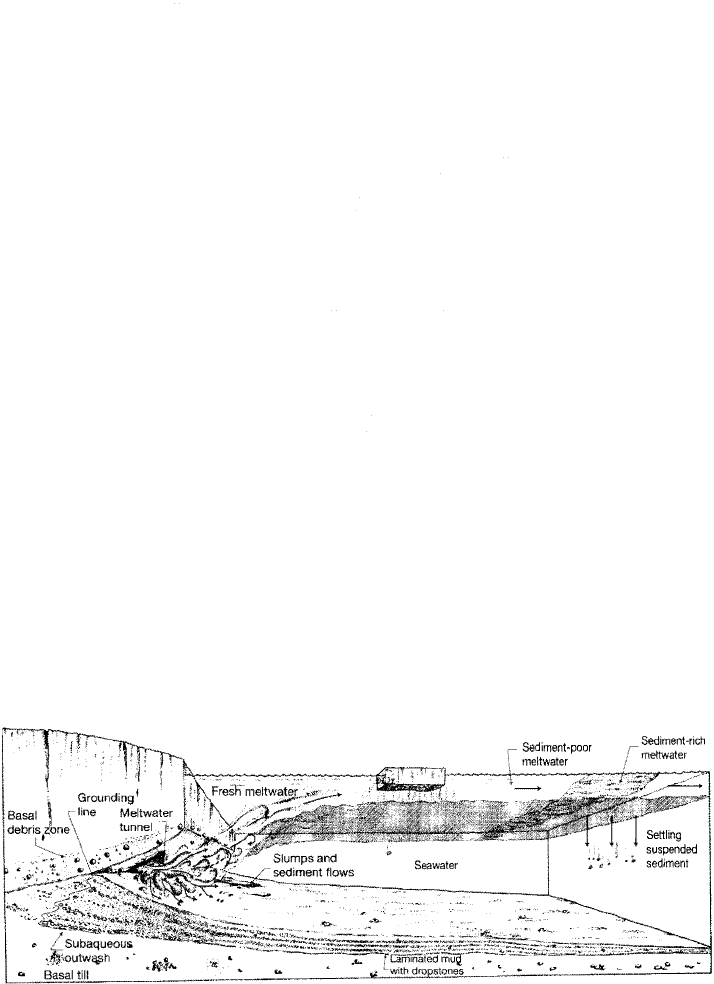

Where glaciers extend beyond the mouths of river valleys to enter the sea,

their sediment load is dumped into the ocean to form glacial-marine sedi

ments. Sedimentation under these circumstances may take place in four differ

ent ways:

1.

Melting beneath the terminus of the glacier allows large quantities of glacial

debris to be released onto the seaoor with little reworking (Fig. 8.30).

2. Large blocks of ice calve off from the front of the glacier and float away as ice

bergs. ese icebergs gradually melt, allowg their sediment load to drop

onto the seafloor, either on the shelf or in deeper water.

3. Fresh glacial meltwater charged with fine sediment can rise to the surface to

form a low-density overflow above denser saline water. Silt and flocculated

clays then gradually settle out of suspension from this freshwater plume.

4. Mixing of fresh meltwater and seawater may produce a high-density under

flow that can carry sand-size sediment seaward.

Glacial Fades

Because the broad glacial environment encompasses the proglacial and periglacial

environments as well as the glacial environment proper, it is necessary, to avoid

confusion, to distinguish between glacial facies deposited directly from the glacier

and facies transported and reworked by processes operating beyond the margins

of glaciers. Furthermore, it is desirable to distinguish between glacial facies de

posited on land and those deposited on the seafloor. Ta ble 8.1 illustrates the range

of sedimentary facies that are affected some way by glacial processes. Many of

these facies are subtypes of facies deposited in fluvial, lacustrine, eolian, shallow

marine, and deep-marine environmen, which are treated elsewhere in this book

Therefore, we focus our discussion here primarily on grounded-ice facies and

proximal marine-glacial facies.

Figure 8.30

Model for glaciomarine sedimentation in front of a wet-based tidewater glacier. Rapid

mixing of fresh water and seawater adjacent to tunnel mouths may produce a high-densi

ty underflow capable of transporting sand-grade sediment and possibly coarser material.

Much

of the fresh glacial meltwater rises to the surface of the sea as a low-density over

flow layer; as this layer mixes with seawater, silt and flocculated clay gradually settle from

suspension. Note also the settling of dropstones from melting ice blocks. [After Edwards,

M. B., 1986, Glacial environments, in Reading, H. G. (ed.), Sedimentary environments and

facies, 2nd ed., Fig. 13.5, p. 453, reproduced by permission of Elsevier Science Publishers,

Amsterdam.]

Facies of continental glacial environments

Gunded ice facies

Glaciouvial facies

Glaciolacusine facies

Facies of proglacial lakes

Facies of periglacial lakes

Cold-climate periglacial facies

Facies of marine glacial environment

Proximal facies

Continental shelf facies

Deep-water facies

8.5 Glacial Systems

281

ur: Eyles, N,, and A. D. Mia I!, 19, Glacial facies, in R G. Walker (ed.), Facies models, 2nd ed : Gtsdence Cana

Reprint r. 1, p. 1-38.

Sediment deposited directly from glaciers on land is called till. Several kinds

of till are recognized, including basal melt-out till, ablation till (supraglacial melt

out

till), and lodent till, deposited under a sliding glacier (Martini et al., 2001 ).

Glacial sediment melted from glaciers in lakes or e ocean is called waterlaid

till. If direct deposition from a glacier cannot be proved, the term diamict is used

for poorly sorted, unconsolidated glacial deposits; the term diamicton is used for

their consolidated equivalents.

Continental lee Fa cies

Grounded Ice Fa cies

Unstratified Diami. Till deposited directly from ice on land in various kinds

of moraines consists of unstratified, unsorted pebbles, cobbles, and boulders

(Fig. 8.31) with an interstitial matrix of sand, silt, and clay. They are thus charac

terized by a bimodal particle-size distribution in which pebbles predominate in

the coarser fraction, with cobbles and boulders scattered throughout (Easter

brook, 1982). Some pebbles are rounded, indicating that they are probably

stream pebbles entrained by the ice. Others may be faceted, striated, or polished

owing to glacial abrasion. Elongated pebbles and cobbles tend to show some

preferred orientation, commonly with their long dimensions parallel to the di

rection of glacial advance. They may also be crudely imbricated, with long axes

dipping upstream. Pebble composition can be highly diverse and may include

rock types derived from bedrock located hundreds of kilometers distant. Sands

d silts are commonly angular or subangular. Much of the silt in glacial de

posits is produced by glacial abrasion and grinding.

Stratified Diami. In addition to deposition directly from melting ice, glacial

debris can be deposited from meltwaters flowing upon (supraglacial), within

(glacial), underneath (subglacial), or marginal to the glacier. The deposits of

these meltwaters form on, against, or beneath the ice and thus are commonly

own as ice-contact sediments. They are reworked to some degree by meltwater

and thus exhibit some stratication. They are also better sorted than sediments

282

Chapter 8 I Continental (Terrestrial) Environments

Figure 8.31

Thiok, poorly stratified, poorly sorted glacial diamict (Quater

nary), Alaska. [Photograph courtesy of Gail M. Ashley.]

deposited directly from ice, commonly lack the characteristic bimodal size distri

bution of direct deposits, and may contain pebbles rounded by meltwater trans

port. These stratified deposits can accumulate in channels or as mounds or ridges

known as kames, kame terraces, or eskers. Kames are small mound-shaped accu

mula

tions of sand or gravel that form in pockets or crevasses in the ice. Kame ter

races are similar accumulations deposited as terraces along the margins of valley

glaciers. Eskers are narrow, sinuous ridges of sediment oriented parallel to the

direction of glacial advance. They are the deposits of meltwater streams that

probably flowed through tunnels within the glacier. The deposits were then let

down onto the subglacial surface after the ice melted. Stratified diamicts are

commonly characterized by slump or ice collapse features, including contorted

bedding and small gravity faults. Stratified glacial facies can include gravels,

sands, and silts, some of which may be extremely well stratified, as illustrated

in Figure 8.32.

Facies of Proglacial and Periglacial Environments

As discussed, meltvvaters issuing from glaciers transport large quantities of glacial

debris downslope and deposit it as glaciofluvial sediment in braided streams or

as glaciolacustrine sediment in glacial lakes, formed by ice damming or moraine

damming. These transported and reworked deposits take on the typical charaoter

istics of the environment which they are deposited; however, they may retain

some characteristics that identify them as glacially derived materials. For exam

ple, the large daily to seasonal fluctuations in meltwater discharge may be reect

ed in abrupt changes in particle size of sediments deposited in meltwater streams

or lacustrine deltas. Sediments deposited in streams or lakes very close to the glac

ier front may also display various slump deformation structures caused by me1t

ing of supporting ice. As mentioned in the discussion of lakes, one of the most

10m

8m

6m

2m

A

Gardner Lake

Stion 10

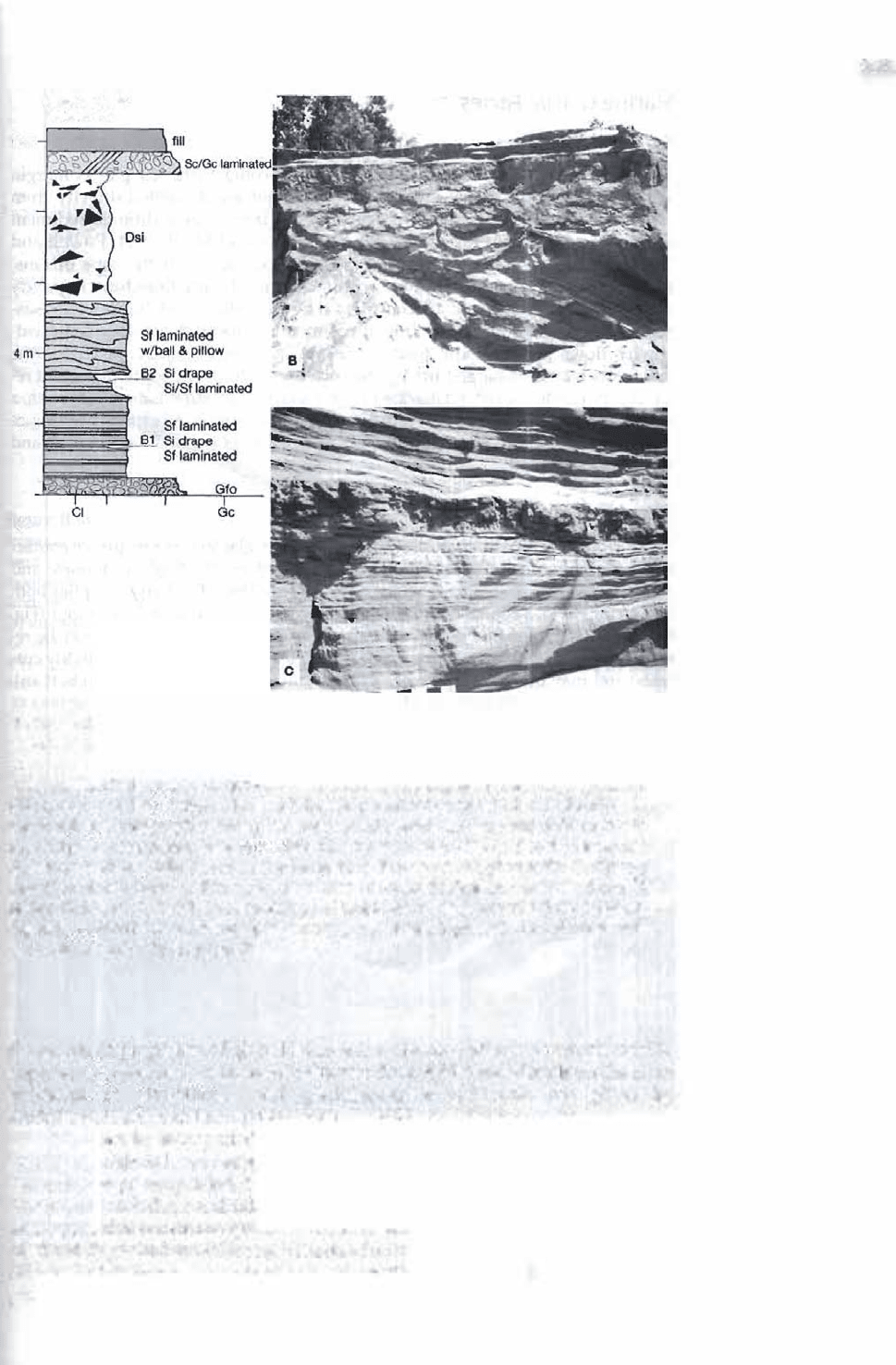

Flgure 8.32

8.5 Glacial Systems

283

A. Ve rtical stratigraphic profile of glacial sediments deposited in an esker system. The envi

ronment is interpreted as ice-tunnel gravel overlain by laminated, marine fan sand and di

amictite.

Lithoacies code: G, gr.ael; S, sand; Si, si

lt

; Dsi, silty diamictite; Cl, clay. Grain

size: c, coarse; f, fine. Other: Bl and 82, bedding surfaces .upon whic dip of surface fan

measured. B. Photograph showing laminated sand overlain by fine and deformed into

ball and pillow structures, In turn overlain by a assive diami(tite {5.S to 9 m interval in

A), interpreted as a debris now on tile fan surface. Person on left gives cale. C. Close-up

vi of laminated sand within a thin diamictite interbed. Scae increments are 5 em. [After

Ashley, C. M., et al., 1991 , Sedimentology of ate Pleistocene (Laurentide) deglacial-phase

deposits, eastem Maine: An example of a temperate marioe grounded ice-sheet margin:

Gl, S. America Spec. paper l61 , Fig. 5, p. 113.]

characteristic properties of glaiat lakes is the pesence of varves, which form in

response to seasonal variations in meltwater flow. Additional details on the har

acteristics of glaciofluvial and glaciolacustrine sediments are given by

Brzikowski and van Loon (11), Maizels (1995), and Ashley (1995).

Sand can ransponted by wind from outwash plains and deposited as

dunes periglacial areas adjacent to glaciers (e.g., Derbyshire and Owen, 1996);

however, the primary wind deposits in many periglacial environments are silts.

Deflation of rk flour and other fine sediment from outwash plains and alluvial

plains provies enormous quantities f silt-size sediment that is transported by

wind and deposited as widespread sheets of fine, well-sorted loess. Because of the

even size of its gras, lss typically lacks well-defined stratification. It is com

sed dominantly of angular grains of quartz but may also contain some clays.

284

C

hapter 8 I Continental (Terrestrial) Environments

Marine Glacial Facies

Proximal Fa cies

In environments where marine water i in direct contact wih the glacier margin

(e.g., Fig 8.33), substantial quantities f sediment are deposited directly from

meltwater conduits or tunnels into subaqueous ans, with addHional sediment

suppied by melting of rafted ice (Fig. 8.34; Eyles and Miall, 1984; Powell and

mack, 1995). Coarse cobbfes and gravels accllmlllate at the tops of fans,

and sands and gravels accumulate within channels owing to sediment gravity

underflows. Mud and sand are contributed by ice melting and "rain-out" of sus

pended sediment. Some reworking vf sediment curs by downslope sediment

gravity flows and episodic traction-current activity. Proximal glacial-marine

sediments may thus range from poorly sorted, prly stratified diamicts that re

semble those deposited on land to coar-grained stratified diamicts, with a

muddy sandy matrix, that may display current-produced stmctures. Melting of

buried ice masses can cause surface subsidence and assodated deformation and

fa ulting of sediment.

Distal Fa cies

Away from the proximal environment in which glaciers are in direct contact

with marine water, glacial sediment is supplied by floating ice masses, and

deposition is dominated by marine processes. Melting of icebergs supplies both

fine sediment and coarse debris to the ocean floor by "rain-out," or faout (Fig.

8.30 and 8.34). Ice-rafted debris deposited on the continental shelves may be re

worked to some degree by marine waves and currents (and possibly turbidity cur

rents) and may be affected by iceberg gunding (where icebergs touch bottom).

In deeper water on the continental shelf, the debris fa llout from floating ice may or

may not be retransported by turbidity currents to deeper water. Ice-rafted debris

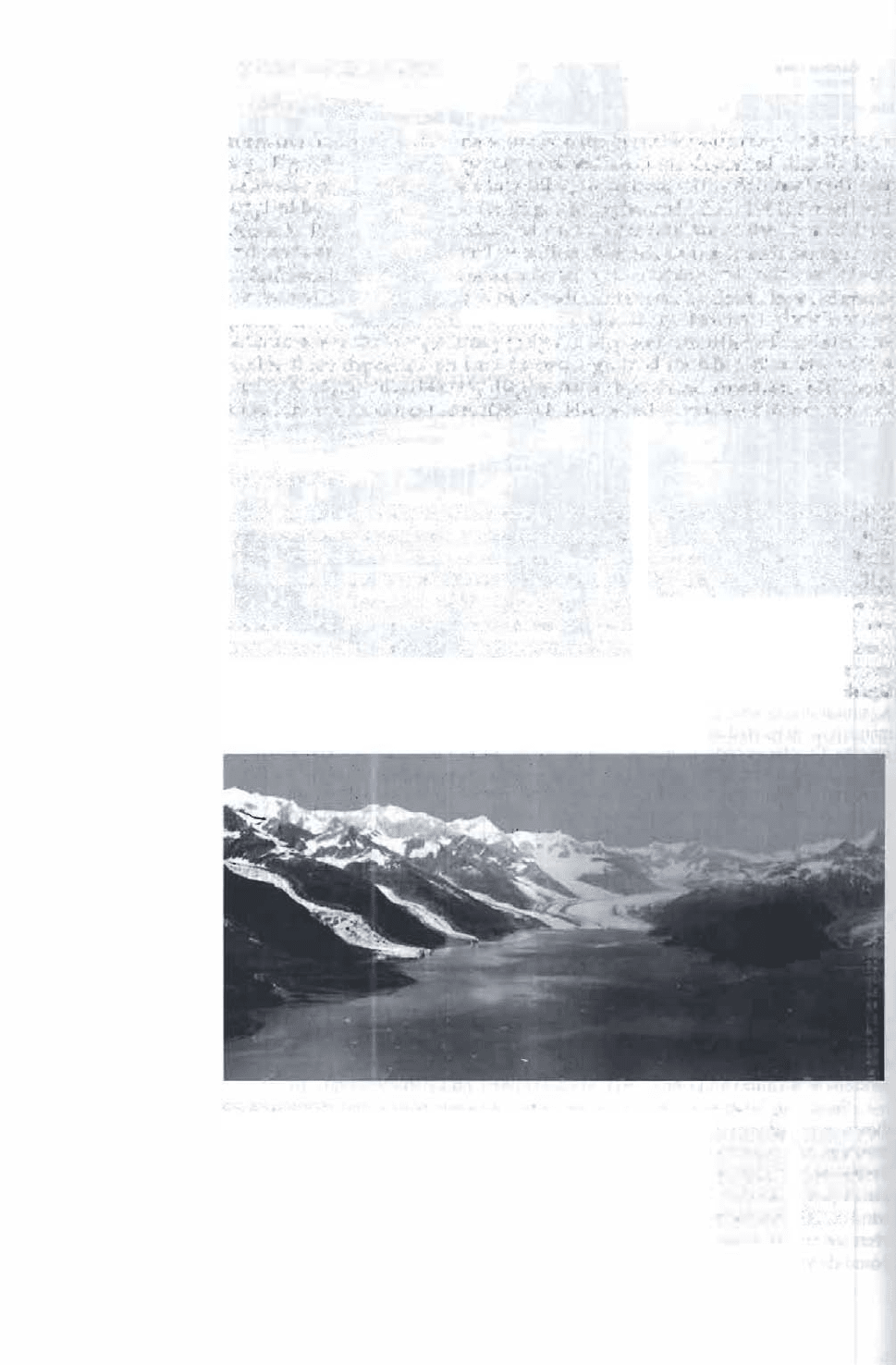

Figure 8.33

Tidewater glaciers flowing into the ocean. Note the nearshore plume of sediment derived

from the melting glaciers and the many small blocks of floating ice. College Fiord Glacier,

Chugach Mountains, southeastern Alaska. [U.S. Navy photog raph, American Geographic

Society Collection archived at the National Snow and Ice Data Center, University of Col

orado, Boulder, and obtained from the Internet at http:/ /-nsidc.colorado.edu, down

loaded Dec. 9, 1998.]

Flgure8.34

8.5 Glacial Systems

285

®

®

Proximal subaqueous sedimentation from glaciers: (1) glacially tectonized marine sedi

ment, (2) lensate lodged diamict units, (3) coarse-grained stratified diamicts, (4) pelagic

muds and diamicts, (5) coarse-grained proximal outwash, (6) interchannel cross-st,atified

sands with channel gravels, (7) resedimented facies (debris flows, slides, turbidites), and

(8) supraglacial debris. Sediment deformation results from ice advances, melt of buried

ice, and ice-turbation. [From Eyles, N., and A. D. Miall, 1984, Glacial facies, in R. G. Walk

er (ed .), Facies models: Geoscience Canada Reprint Ser. 1, Fig. 8, p. 20, reprinted by per

mission of Geological Association of Canada.]

that settles to the deep ocean floor is probably little modified by further deposi

tional processes, except for deposition of a mantle of hemipelagic or pelagic

sediment. In general, glacial-marine sediments are distinguished from ground

ed glacial diamicts by the presence of some stratification and from all on-land

glacial

diamicts by the presence of marine fossils and dropstones. Dropstones

are scattered cobbles or boulders that drop to the seafloor from melting ice

blocks or iebeFgs. FossH evidence that particularly suggests a glacial-marine

origin includes fossils preseFved in growth position as whole shells (i.e., fossils

enfombed by fallout sediment); marine molluscs or barnacles attached to

glacially faceted pebbles; preservation of delicate ornamentation on shells; and

the presence of forams and diatoms in the matri material (Easterbrook, 1982).

Veical Facies Successions

Successive advances and retreats of valley glaciers and ice sheets produce com

plex vertical successions of facies as ice progressivety overrides proglacial envi

nments during glacial advance, and conversely as direct ice deposits and

ice-contact deposits are reworked in the proglacial environment as a glacier re

treats. These facies are much too varied and complex to attempt description here;

however, Figure 8.35 illustrates some typical vertical profiles that might develop

different parts of a glacial environment during a single phase of glacier advance

d retreat. e also Brodzikowski and van Loon (1991, Chapter 9) and Edwards

(1986, p. 46566).