Bogucki P., Crabtree P. Ancient Europe 8000 B.C.-A.D. 1000: Encyclopedia of the Barbarian World. Volume 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

at times complex combinations of compass-drawn

curves, most often filled with incised basketry. Not

all are of the highest technical quality, but the best

of them, such as that from Desborough in North-

amptonshire (fig. 3), are products of exceptional

craftsmanship. There are other insular innova-

tions—on both islands—such as bronze horse bits,

often with elaborate cast decoration; finely made

spun-bronze vessels; and the late, specifically British

developments in scabbard decoration. An impor-

tant artistic creation of this period is a magnificent

horned helmet of bronze, also from the Thames,

which has enameled ornament and raised curvilinear

designs reminiscent of those on some of the Snet-

tisham torcs.

The Roman occupation of much of Britain dur-

ing the middle of the first century

A.D. precipitated

a decline in Celtic artistic traditions. In Ireland,

however, these traditions continued, eventually re-

ceiving new life and vigor through the work of the

monastic craftsmen who devoted much of their skill

to the glory of God. Metalworking reached new

heights of technical and artistic perfection, and the

same outstanding skills are displayed in the great il-

luminated manuscripts and the finely carved high

crosses. New motifs were introduced, especially in-

terlacing decoration and animals of many forms, en-

tirely alien to the original Celtic artificer. There

were many new mediums, such as millefiori glass

and polychrome enamel. By the eighth century Irish

craftsmanship had risen to astonishing heights of

technical skill and artistic sophistication never again

to be achieved.

See also Hochdorf (vol. 1, part 1); Irish Bronze Age

Goldwork (vol. 2, part 5); Celts (vol. 2, part 6);

Hallstatt (vol. 2, part 6); La Tène (vol. 2, part 6);

The Heuneburg (vol. 2, part 6).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Megaw, M. Ruth, and J. V. S. Megaw. Celtic Art: From Its

Beginnings to the Book of Kells. Rev. ed. New York:

Thames and Hudson, 2001.

Moscati, Sabatino, et al., eds. The Celts. New York: Rizzoli,

1991.

Raftery, Barry, ed. (with Paul-Marie Durval et al.) Celtic Art.

Paris: UNESCO, Flammarion, 1990.

B

ARRY RAFTERY

6: THE EUROPEAN IRON AGE, C. 800 B.C.– A.D. 400

190

ANCIENT EUROPE

THE EUROPEAN IRON AGE, C. 800 B.C.– A.D. 400

IRON AGE SOCIAL ORGANIZATION

■

The Iron Age in temperate Europe, inland from the

Mediterranean basin, lasted for some eight hundred

years. Its start is marked by the local adoption of

iron to manufacture edge tools, such as axes and

swords; there may have been contemporary social

changes related to the near collapse of exchange

patterns provoked by the declining importance of

tin and copper. It ended over much of the Conti-

nent with the expansion of the late Roman Republic

and, subsequently, the early Roman Empire during

the last two centuries

B.C. and the first century A.D.

In more northerly areas, for instance, Ireland, the

influence of Rome was very muted, if never entirely

absent. There, many characteristics of the Iron Age

either continued into or reasserted themselves dur-

ing the first millennium

A.D. In a real sense, in such

areas the Iron Age effectively lasted for several more

centuries. Elsewhere, as in southern Germany, the

last century

B.C. is marked by the arrival of another

new population, the Germans, whose appearance

broadly coincided with marked changes in the Iron

Age archaeological record.

For the period between c. 800

B.C. and the

beginning of

A.D. 1, the evidence provided by ar-

chaeology is complemented by information drawn

from other sources. Of very great importance are

surviving texts from the classical world. The earliest

of them contain scant, almost tantalizing informa-

tion about conditions in the middle of the first mil-

lennium

B.C.; written sources thereafter became

more numerous, especially from the first century

B.C. These texts outline some of the customs and

conduct of the peoples with whom the Greek

and Latin authors, or their sources, came into con-

tact. Given that they represent more or less contem-

porary accounts of the Iron Age communities, these

accounts have great value, but they cannot be con-

sidered dispassionate, unbiased perspectives. On the

one hand, they are outsiders’ views—descriptions of

what anthropologists sometimes term “the

Other”—on occasion composed by authors with a

vested interest in political affairs within the societies

they are describing. The accounts thus display a ten-

dency to focus on characteristics their original read-

ership would have found puzzling, if not unaccept-

able, thus justifying Roman intervention.

Julius Caesar’s description of his conquest of

Gaul (corresponding in extent more or less to pres-

ent-day francophone Europe) is one of the fullest

such accounts. Some historians have considered his

De bello Gallico the unembellished narrative of a

straightforward military man, recounting his actual

experiences; others argue that it is a consciously lit-

erary work that in some respects is simply propagan-

da. The dominant view sits between these two ex-

tremes but would not envisage Caesar’s text as

“value free.” Furthermore, these texts were com-

posed according to the intellectual conventions of

their day. Unacknowledged copying of earlier au-

thors was an acceptable practice, allowing for the

possibility that descriptions of native societies may

have been out of date by the time they were repeat-

ed. Far from being attempts at objective ethnogra-

phy or history, texts were framed within contempo-

rary philosophical perspectives.

ANCIENT EUROPE

191

A noteworthy example is Agricola, the history

of Agricola, the governor of Britain, written by his

son-in-law, the Roman historian Tacitus. Tacitus

recounts the lead-in to his father-in-law’s crushing

defeat of the Caledonii in Scotland, using simply the

auxiliary forces at his command, in the late first cen-

tury

A.D. The speech Tacitus puts into the mouth of

the native war leader is not a dispatch from the bat-

tlefield but rather an Italian intellectual author’s

view of what the native leader Calgacus ought to

have said: in effect the perspective of an imagined

“noble savage.” By contrast, the Roman historian

Livy’s account in The History of Rome of the arrival

of the Celts in Italy is prefaced by the story of a king

in central France, Ambigatus, who instructs his

nephew to lead the people southward. Is this an in-

dication of fosterage—the often forcible taking in of

the children of people of dependent status—among

the elite, a practice later recorded in early historic

Ireland? Or is it the pattern of succession? One can-

not be sure, for nothing more is known of Ambiga-

tus’s family circumstances. As the key individuals in

this story are a king and his two nephews (the other

being told to lead a portion of the tribe into central

Europe) rather than members of a nuclear family,

speculations on the relationship between the two

generations are possible.

Although literacy made a late appearance in the

Iron Age of temperate Europe (which is known, for

example, from the evidence of graffiti scratched on

ceramics and legends on coins), no contemporary

documents from the late pre-Roman barbarian so-

cieties of temperate Europe north of the Alps or

Pyrenees survive. The archaeological record thus is

protohistoric in the sense that it is “text aided”

uniquely through external, classical accounts. Be-

cause the Roman takeover of temperate Europe was

not complete, it has been suggested that more mod-

ern literature, eventually written down in early

Christian Ireland in the late first millennium

A.D.,

includes elements transmitted orally from much ear-

lier times, in effect providing a window on the Iron

Age. Later commentators note, however, that de-

tailed study indicates that this view gives rise to

problems, as conscious changes typically are intro-

duced during the transmission process. For this rea-

son, scholars are increasingly cautious about using

the Irish evidence to illuminate circumstances—

including social conditions—within pre-Roman

Iron Age continental Europe and Britain.

Another strand of evidence consists of lan-

guage, as contained essentially in place, tribal, per-

sonal, and similar names as well as in brief inscrip-

tions. This evidence is recorded in Greek or Latin

scripts or in local variants of these scripts, as, for ex-

ample, in the Iberian area of Mediterranean Spain.

Many of these western and central European

sources indicate languages conventionally ascribed

to the Celtic family, beginning with Lepontic in

northern Italy and stretching west to Celtiberian in

Spain. In the later centuries

B.C., such records, once

very rare, became more common.

PEOPLES: CELTS AND OTHERS

It has been conventional practice to label the best-

fit evidence of material culture with the same name

as the language group and, where it is known, the

classical term for the people in that area. In this way,

the material culture of the Iron Age in west-central

Europe attributable to the end of the first Iron Age

(or Hallstatt period) and its second Iron Age succes-

sor (La Tène culture, from the middle of the fifth

century

B.C.) have been termed “Celtic.” The art of

that period, much of it produced for elite patrons

and some of it magico-religious in character, is la-

beled “early Celtic art.”

Another, more questionable practice has been

to use the classical, or the later Irish, historical

sources or the two in combination to provide de-

scriptions of Celtic society as a complement to the

evidence furnished by field archaeology. Such social

generalizations are idealized: they disregard the real

differences through time and from region to region

visible in the archaeological record during the sever-

al centuries of the Iron Age, and thus they carry in-

herent dangers. The correlation of a set of material

culture with an assumed linguistic affiliation—and

beyond that automatically to an ethnic label—often

is insecure. To say this is not, however, to deny that

there were groups within temperate Europe that

their neighbors called Celts or Gauls as well as Iberi-

ans, Scythians, and Germans. It is equally unreliable

to assume that groups so named also automatically

subscribed to a particular ethnically defined form of

society, unchanging through the several centuries of

the Iron Age.

6: THE EUROPEAN IRON AGE, C. 800 B.C.– A.D. 400

192

ANCIENT EUROPE

CHANGES THROUGH TIME AND

THEIR SIGNIFICANCE

By the end of the Iron Age (La Tène D, from the

later second century

B.C.), the various sources com-

bine to indicate the presence of socially and politi-

cally elaborate societies, witnessed, in particular, by

the appearance of settlement sites of a scale and

complexity not previously encountered. Termed op-

pida, these sites have a strong claim to having been

the first indigenous temperate European towns. It

would be incorrect, however, to envisage the Iron

Age as a straightforward evolutionary sequence

from simpler toward increasingly complex societies,

numbers of which had crossed or were close to the

threshold for definition as a state by the time of the

Roman conquest. Most later models of Iron Age

evolution suggest that periods and regions marked

by increasing complexity were offset by local or re-

gional collapses or reversions. In other areas—parts

of northern Britain are a case in point—there is dis-

tinctly less evidence for social hierarchies in the

available evidence for the later first millennium

B.C.

than can be gleaned for other areas, such as central

France or southwestern Germany. Generally, the

rhythm and periodicity of apparent changes and

their general scale are matters of debate, as are the

mechanisms—internal to temperate European so-

cieties or external to them—that lay behind these

oscillations.

In most explanations, the nature and scale of

contacts between the heartland of the Continent

and the civilizations colonizing the Mediterranean

(and Black Sea) littorals offer a key driving force un-

derpinning assumed social, political, and economic

changes during the Iron Age. Archaeological finds

suggest economic contacts, which then can be used

to account for social and political developments per-

ceived in that record or in contemporary historical

sources. Seaborne colonization by the Greeks, con-

temporary with the establishment of their leading

western colony at Massalia (on the site of present-

day Marseilles in southern France) in 600

B.C., is a

case in point. Their equivalent establishment of set-

tlements along the northern fringe of the Black Sea

and in the Crimea is another example. Also impor-

tant is Phoenician and subsequent Carthaginian ac-

tivity, especially in Iberia, which resulted not only

in contact with native societies in that area but also

in the blocking of Greek access to Iberian metal ores

from Galicia and elsewhere. In due course, Roman

conflict with the Carthaginians drew them into mili-

tary activity in Iberia in late Republican times and

set in train their northward expansion from the

Mediterranean basin. Another important current

was Etruscan colonization of the Po Valley of north-

ern Italy and the head of the Adriatic Sea, which

brought them to the ends of the Alpine passes lead-

ing from the Continental heartland.

Commodities manufactured in the Mediterra-

nean civilizations appear in autochthonous con-

texts, including richly accompanied burials that are

redolent of high status, for example, in southwest-

ern Germany. It seems excessive, however, to attri-

bute exclusively to these southern contacts the

motor for social change in the Continental heart-

land. Such a perspective implicitly assumes that the

constitution of a society necessarily realigns itself on

that of an expansive neighbor perceived to be cul-

turally more developed—thus that Hellenization

(emulation of Greek traits), like Romanization in

subsequent centuries, effectively would be irresist-

ible. The anthropological literature contains many

cases that show that in such circumstances the adop-

tion of traits and influences can be highly selective,

if they are not entirely rejected.

A refinement of this perspective envisages later

prehistoric temperate Europe as a periphery strong-

ly influenced by, if not dependent on, a core area in

the Mediterranean civilizations. This application of

world systems theory effectively transfers back into

the ancient world characteristic patterns that have

been recognized in modern times since the great pe-

riod of European expansion across the world. Given

the very different socioeconomic conditions of an-

cient times, let alone the much more rudimentary

nature of transport networks, it is a moot point

whether or not such a perspective is realistic for the

middle of the first millennium

B.C. In any case, a

problem of the world systems approach is that it re-

duces elite decision makers on the assumed periph-

ery to the status of bit actors, puppets on strings

pulled from the south, and thus too readily elimi-

nates them as knowing agents in establishing their

own destinies.

If this type of approach has any validity, it is

most likely to be for the last two centuries

B.C.,

when the archaeological evidence, in particular, in-

dicates that for some regions the scale and frequen-

cy of southern contacts were much greater than they

IRON AGE SOCIAL ORGANIZATION

ANCIENT EUROPE

193

were previously. In sum, the change is from ex-

change dominated by the infrequent arrival of indi-

vidual high-status items manufactured in the cities

of Etruria or in the Greek colonies (a pattern charac-

teristic of the centuries in the middle of the first mil-

lennium

B.C.) to the arrival of mass-produced goods

of distinctly less-elevated status during the century

or so before Caesar’s campaigns in the 50s

B.C.

WINE, FEASTING, AND HORSES AS

INDICATORS OF SOCIAL CHANGE

This change is best seen in the accoutrements of al-

cohol consumption, in particular, the drinking of

wine. For much of the temperate European Iron

Age (things began to change from about the second

century

B.C.), wine was essentially an Italian product

and the strongest—and probably the most readily

storable—drink available. In Late Hallstatt and

Early La Tène contexts, in both high-status burials

and settlements, fine vessels associated with the con-

sumption of wine occur in small numbers. Direct

evidence of the wine itself, in the form of transport

amphorae, is rare in areas away from the immediate

hinterland of the Mediterranean. By contrast, from

the second century

B.C. (in La Tène C and D peri-

ods), the dominant finds in the archaeological

record from some sites and areas of temperate Eu-

rope are Italic (made in Italy but not by Italians)

wine amphorae. The quantities of discarded exam-

ples (each would have held some 25 liters of wine)

suggest a level of commercial interaction not previ-

ously seen, as well as the much wider role of this ex-

otic commodity in lubricating social and political re-

lationships in inland Europe.

In some cases, the numbers of amphorae, the

manner of their discarding, or their association with

prolific quantities of animal bones strongly suggest

large-scale feasting, a significant activity in cement-

ing social and political obligations in the Iron Age

world. There clearly was a major change in the

quantities of wine that were accessible and in the so-

cial ways this commodity was employed. As ever,

the nuances of such differences need to be recog-

nized: both archaeological finds and historical ac-

counts make it plain that southern merchants bring-

ing wine freely traded in certain regions (e.g.,

marginal to present-day Belgium) while other re-

gions received modest to plentiful quantities.

Other factors profoundly influenced the nature

of Iron Age social organization on a wider scale.

Since the Neolithic, the products of agricultural sys-

tems had underpinned all communities. In the Iron

Age, there is evidence from numerous regions of

considerable agricultural diversification as well as

the storage of agricultural surpluses, using several

different technologies and to an extent not previ-

ously encountered in temperate Europe. Such evi-

dence underscores the likelihood of rising popula-

tions and of larger aggregations of people resident

on some settlement sites than had previously been

the case, again with implications concerning the

form and operation of society.

In the case of livestock, particular attention

needs to be paid to the horse. Westward of the Eu-

ropean steppes, evidence for horses is much more

widespread in the Iron Age record than in earlier

times. One piece of evidence is horse equipment,

notably a wide range of horse bits, suggesting subtle

control over the ridden horse. There are also bones

of the animals themselves and iconographic repre-

sentations of horses, for example, on high-status

decorated metalwork, including appliqué panels

and small axes, from certain graves in the cemetery

at Hallstatt (in the Salzkammergut, Austria). Both

four- and two-wheeled vehicles also are present, as

inclusions in elite graves and in more prosaic set-

tings. The ridden horse, horse-drawn chariots and

carts, and subsequently, the development of cavalry

provided opportunities for a rapidity of overland

movement not previously available, and they facili-

tated the ready exercise of direct political and social

control over more extensive territories. Folk migra-

tion was an accessible method for social and political

change and one to which the classical sources testi-

fy, even if some archaeologists believe it was rarely

undertaken. Equally, evidence from some areas in-

dicates the emergence of hunting from horseback as

an elite sport, unconnected with satisfying subsis-

tence needs.

THE FORM OF SOCIETY—ELITES

There are plentiful indications that European Iron

Age societies were hierarchical, although the depth

of elaboration of that hierarchy seems to have varied

across time and space. For much of the period, the

social and political elite groups conformed to what

would be anticipated in complex chiefdoms, with

succession to important office being determined by

real or imagined kinship links. Archaeological evi-

6: THE EUROPEAN IRON AGE, C. 800 B.C.– A.D. 400

194

ANCIENT EUROPE

dence suggests that such societies used several

methods, including redistribution and gift ex-

change, to formulate and maintain wider linkages.

By the La Tène D period (from the later second

century

B.C.), in some areas substantial changes had

occurred. For certain of the Continental tribal areas

(usually known by their Latin descriptor as civi-

tates), political command, and by extension, social

leadership had shifted from the king and his retinue

to an elected magistracy. (The chief of this magistra-

cy was termed a vergobretus, a Celtic loanword that

appears in Caesar’s text.) The magistracy was select-

ed annually from among the oligarchical group that

constituted the elite. Place of residence was begin-

ning to oust kinship links, assumed or real, in defin-

ing group membership. Caesar’s text strongly sug-

gests that both these systems continued during this

period, for his account includes plenty of individuals

accorded the Latin title rex, perhaps a fair reflection

of the fluidity of Iron Age political and social rela-

tions at this time in the face of powerful external

military aggression.

Magistrates appear to have been solely male,

whereas women could emerge as the leaders in

more conventionally organized societies, as was cer-

tainly the case in southern Britain during the first

century

A.D. That females could hold high rank also

is suggested in numerous contexts by the funerary

record, where variations in the quality and number

of grave goods equally points to subtle gradings

within sociopolitical ranks, perhaps akin to what lit-

erary texts indicate more particularly for Ireland in

the first millennium

A.D.

Elite female graves are recognizable from Hall-

statt C onward (the eighth century

B.C.); they gen-

erally are marked by ranges of grave goods in which

jewelry (and sometimes mirrors) form a significant

component, with weaponry rare or absent. Normal-

ly, wealthy female graves are attributed to the socio-

political elite, as in the rich female grave from Rein-

heim in Germany. In other instances, it is possible

that the wealth in the grave is indicative of a spiritual

rather than a political leader. Christopher Knüsel

has suggested, for example, that the grave at Vix in

Burgundy, dating to the fifth century

B.C. (Hallstatt

D), held the slightly deformed body of a middle-

aged woman whose local importance may have been

religious. She is accompanied by a dismantled

wagon, a high-quality gold necklet or torc (a rigid

penannular collar or neck ring), and a spectacular

imported bronze wine krater, or large vase—the

biggest surviving vase from the Greek world. In

other instances, grave goods suggest that brides

may have been exchanged over considerable dis-

tances in continental Europe. Female graves from

northeastern France (dating to the third century

B.C.) with paired anklets may well contain girls orig-

inally from the heartland of central Europe, where

this particular fashion was widespread.

The presence of grave goods in some of the rel-

atively rare children’s graves suggests that status in

the societies to which they belonged was ascribed

rather than attained. In some instances, children are

accompanied by smaller examples of adult grave

goods (e.g., bracelets), and in others their positions

within cemeteries or under barrows intimate their

significance within their community. As in many an-

cient societies, infants and young children are un-

derrepresented in the funerary record, but this may

be a reflection either of their status or of the use of

burial practices less susceptible to archaeological de-

tection. More generally, both inhumation and cre-

mation are encountered, sometimes in the same

cemetery (as at Hallstatt), and the change from one

to the other need not have any straightforward so-

cial significance.

The literary sources provide details of the signif-

icance of religious and educational specialists within

society, notably the druids. They make it clear, too,

that the activities of such elites could extend beyond

the polities in which they were based. From numer-

ous areas, archaeological evidence makes plain the

fact that many activities had a ritual dimension (in-

cluding such prosaic acts as the discarding of rub-

bish in disused underground storage pits within set-

tlements). On some sites—notably, the so-called

Picardy sanctuaries of northeastern France—

ritualized acts seem to have been key, to judge from

the clear patterns in the archaeological finds recov-

ered from them. Deliberately damaged equipment

and weaponry, animal bones, and human remains

showing a range of postmortem manipulations bear

witness to practices involving such religious practi-

tioners that can be gleaned only indirectly. The

most famous such locale is a small enclosure within

a settlement at Gournay-sur-Aronde, in the valley of

a tributary of the River Oise, to the north of Paris.

IRON AGE SOCIAL ORGANIZATION

ANCIENT EUROPE

195

OTHER GROUPS: WARRIORS,

SPECIALISTS, ARTISANS,

AND FARMERS

Among other groups prominent within society that

can be recognized from the written sources and

from the archaeological record are specialists of va-

rying degrees of skill. These people include musi-

cians and poets, craftspeople, and warriors. The ac-

companiments in male graves indicate that warriors

constituted a significant proportion of male adults

in some areas. The grave goods that typically identi-

fy them are swords (of iron, sometimes encased in

elaborate decorated bronze sheaths) and spear-

heads. Defensive equipment, which is rarer, is domi-

nated by metal shield fittings (usually for shields

made of organic materials that have rotted away)

and helmets, the latter including ornate examples

displaying the status of the wearer rather than sim-

ple protective military gear.

It is noteworthy that some of the most elabo-

rate examples of such equipment (for men and

sometimes their horses) come from the apparent

margins of the Celtic domain, if not beyond. Such

places include southern Italy, western France, Ro-

mania, and northern Britain, perhaps suggesting

that the insignia were of special importance in these

peripheral settings. Military protection appears to

have been a significant element in the glue that held

Celtic societies together, if indications from both

earlier Continental written sources and later insular

ones are considered. There are hints in the texts of

the importance of clientship—the formalization of

patron-client relations through the development of

mutual obligations. The provision of military pro-

tection seems to have been a key component of such

arrangements.

There also are signs of profound changes in the

nature of the social and political relationships that

lay behind the establishment of military forces dur-

ing the last half-millennium

B.C. For the Early Iron

Age, it is easy to envisage military service as arising

through real or assumed kinship links, clientship ob-

ligations, indebtedness, and similar causes and as

being both temporary and intermittent in character.

By the end of this period, however, there were sig-

nificant changes. In some instances, armies still had

to be called together at moments of crisis by hold-

ing a hosting (assembling an irregular army from di-

verse groups with the express purpose of battle), as

Caesar recounts. In other cases, standing armies

were associated with particular civitates (or perhaps

their constituent parts, the pagi), which could be

paid in coin, a practice initially learned in mercenary

service to the Hellenistic kings around the Aegean.

Unsurprisingly, military leadership seems to have

been a high-status responsibility and was main-

tained in Gaul, for example, after its defeat by

Rome. Cavalry units, in particular, kept their native

commanders and simply transferred their allegiance

to their new masters as auxiliary troops.

Specialists also seem to have had considerable,

but perhaps variable, status in society. Some are rec-

ognizable in death from the equipment placed in

their graves, as, for example, the medical doctor of

the La Tène C period identified from his instru-

ments at Obermenzing near Munich in Bavaria,

Germany. In other cases, tools have been found in

workshops or elsewhere on settlement sites. The

Late Iron Age toolkit found at Celles in central

France is appropriate to marquetry or similar deco-

rative work on furniture, and some of the finest

items of early Celtic art, such as the helmet from

Agris in western France and a few of the vehicles,

imply collaborations among several artisans skilled

in different materials or in different trades.

Localized distributions of certain artifacts, such

as certain varieties of Late Hallstatt brooches, sug-

gest that they may have been made directly for elite

patrons on particular sites. Other types of objects

(most particularly in La Tène D) are much more

standardized over wide areas of the Continent and

may betoken the work of independent craft work-

ers. At some sites, artisans engaged in the same craft

are clustered in limited sectors, as in the case of

enamel workers found inside the main gate at the La

Tène D oppidum of Mont Beuvray in Le Morvan,

France. Such groupings may be considered socially

significant. Overall, however, skilled specialists as

well as the general run of artisans must have consti-

tuted the dependent classes of later Iron Age socie-

ties, as described by Caesar: they probably would

have been substantially outnumbered by agricultur-

al laborers, peasants, and small farmers.

SLAVERY

Was slavery a component of Iron Age societies in

temperate Europe? For most areas and periods, the

evidence is either ambiguous or nonexistent, but

6: THE EUROPEAN IRON AGE, C. 800 B.C.– A.D. 400

196

ANCIENT EUROPE

there are exceptions. Toward the end of the Iron

Age, in western continental Europe and southern

Britain, chains and similar accoutrements of slavery

become more common in the record and probably

are indicative of long-distance movements of slave

labor. It often is suggested that captives taken in war

were traded down the line across the Continent to

the slave-based societies of the Mediterranean even

in earlier times. Such captives were exchanged for

the luxury products recovered from, for example,

rich Hallstatt graves, although the earlier classical

sources suggest that servile labor was obtained

nearer to hand.

Less certain is the extent to which later Iron Age

societies in temperate Europe were themselves slave

owning as opposed to exporters of prisoners. Analo-

gy with later Ireland might indicate that slavehold-

ing already was established, and it also is possible

that the development of large-scale extractive indus-

tries might have relied to some extent on slave

labor. Shoe sizes have been pointed to as evidence

that children were put to work extracting rock salt

at Dürrnberg in Austria, and the open-air gold

mines of Limousin in France might have been

worked by slave laborers. Overall, we can conclude

that in the Iron Age, as in later times, social struc-

tures and rates of social change in barbarian Europe

probably varied and did not conform closely to a

pan-Continental norm.

See also Celts (vol. 2, part 6); Hallstatt (vol. 2, part 6); La

Tène (vol. 2, part 6); Germans (vol. 2, part 6);

Oppida (vol. 2, part 6); Iron Age Feasting (vol. 2,

part 6); La Tène Art (vol. 2, part 6); Greek

Colonies in the West (vol. 2, part 6); Etruscan Italy

(vol. 2, part 6).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Arnold, Bettina, and D. Blair Gibson, eds. Celtic Chiefdom,

Celtic State: The Evolution of Complex Social Systems in

Prehistoric Europe. New Directions in Archaeology.

Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

Audouze, Françoise, and Olivier Buchsenschütz. Towns, Vil-

lages, and Countryside of Celtic Europe: From the Begin-

ning of the Second Millennium to the End of the First

Century

B.C. Translated by Henry Cleere. Blooming-

ton, Ind.: Batsford, 1991.

Bintliff, John. “Iron Age Europe in the Context of Social

Evolution from the Bronze Age through to Historic

Times.” In European Social Evolution: Archaeological

Perspectives. Edited by John Bintliff, pp. 157–225.

Bradford, U.K.: Bradford University, 1984.

Collis, John R. The European Iron Age. London: Routledge,

1995.

Cunliffe, Barry W. The Ancient Celts. Oxford: Oxford Uni-

versity Press, 1997.

———. Greeks, Romans, and Barbarians: Spheres of Interac-

tion. London: Batsford, 1988.

Dietler, Michael. “Feasts and Commensal Politics in the Po-

litical Economy: Food, Power, and Status in Prehistoric

Europe.” In Food and the Status Quest: An Interdisci-

plinary Perspective. Edited by Pauline Wilson Wiessner

and Wulf Schiefenhövel, pp. 87–125. Oxford: Berg-

hahn Books, 1996.

Fitzpatrick, Andrew. “‘Celtic’ Iron Age Europe: The Theo-

retical Basis.” In Cultural Identity and Archaeology: The

Construction of European Communities. Edited by Paul

Graves-Brown, Siân Jones, and Clive Gamble, pp. 238-

255. London: Routledge, 1996.

Gibson, D. Blair, and Michael N. Geselowitz, eds. Tribe and

Polity in Late Prehistoric Europe: Demography, Produc-

tion, and Exchange in the Evolution of Complex Social

Systems. New York: Plenum, 1988. (Includes Bettina

Arnold’s essay on slavery.)

Green, Miranda J. Exploring the World of the Druids. Lon-

don: Thames and Hudson, 1997.

Green, Miranda J., ed. The Celtic World. London: Rout-

ledge, 1995.

James, Simon. Exploring the World of the Celts. London:

Thames and Hudson, 1993.

Knüsel, Christopher. “More Circe Than Cassandra: The

Princess of Vix in Ritualised Social Context.” European

Journal of Archaeology 5, no. 3 (2002): 275–308. (The

status of the most important Hallstatt princess re-

evaluated.)

Kristiansen, Kristian. Europe before History. Cambridge,

U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Kruta, Venceslas. Les Celtes: Histoire et dictionnaire des ori-

gines à la romanisation et au christianisme. Paris: Rob-

ert Laffont, 2000. (Long introductory essay and useful

gazetteer.)

Megaw, M. Ruth, and J. Vincent S. Megaw. Celtic Art: From

Its Beginnings to the Book of Kells. Rev. ed. New York:

Thames and Hudson, 2001.

Moscati, Sabatino, ed. The Celts. New York: Rizzoli, 1999.

Sims-Williams, Patrick. “Genetics, Linguistics, and Prehisto-

ry: Thinking Big and Thinking Straight.” Antiquity 72

(1998): 505–527.

Wells, Peter S. Beyond Celts, Germans, and Scythians: Ar-

chaeology and Identity in Iron Age Europe. London:

Duckworth Academic, 2001.

I

AN RALSTON

IRON AGE SOCIAL ORGANIZATION

ANCIENT EUROPE

197

THE EUROPEAN IRON AGE, C. 800 B.C.– A.D. 400

GREEK COLONIES IN THE WEST

■

FOLLOWED BY FEATURE ESSAY ON:

Vix . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 205

■

Between 750 and 550 B.C. a number of Greek cities,

both in modern Greece and on the west coast of

modern Turkey, established daughter cities along

the shores of the Mediterranean, Adriatic, and Black

Seas. This process has become known as “Greek col-

onization.” In contrast to colonizing actions of

modern nation-states, however, this expansion of

individual Greek city-states was not centrally direct-

ed, and there was no single purpose. Among the

reasons for the establishment of particular towns

were overpopulation in the mother cities, need for

larger supplies of grain than were available in

Greece, and improvement of trade relations with

different peoples on and beyond the shores of the

Mediterranean Sea. Both Greek historical sources

and archaeological investigation provide informa-

tion about the founding and growth of the new

towns and about relations between them and other

peoples.

MASSALIA

The most important Greek town established in the

western Mediterranean was Massalia, on the site of

modern-day Marseille, France’s second-largest city.

Archaeological evidence from the lands around the

mouth of the Rhône River show that, during the

second half of the seventh century

B.C., merchants

from abroad were trading with the indigenous peo-

ples. Pottery, ceramic amphorae that had carried

wine, and bronze vessels from Greek and Etruscan

workshops appear on settlements and in burials after

about 630

B.C., indicating that this region was being

opened to seaborne trade by the Mediterranean

urban civilizations. It is not known precisely who

these early merchants were—probably the peoples

called Etruscans and Greeks. They traveled in rela-

tively small ships along the Mediterranean coasts,

trading in wine, ceramics, and other luxury goods.

Numerous shipwrecks in the shallow waters of the

Mediterranean coasts provide underwater archaeol-

ogists with rich information about boat technology

and about the character of their cargoes.

Around 600

B.C. Greeks from the city of Pho-

caea, a community in Ionian Greece, now located

on the west coast of Turkey, founded Massalia, the

first permanent Greek settlement known in the re-

gion. The settlers were attracted by the excellent

natural harbor, with its entrance protected from

Mediterranean storms; the hill to the north that

provided ideal settlement land; and the proximity to

the mouth of the Rhône River, the principal water-

way that linked interior regions of Europe with the

western Mediterranean. The site was close enough

to the river’s mouth to provide easy access and allow

control of the river but far enough away to avoid the

198

ANCIENT EUROPE

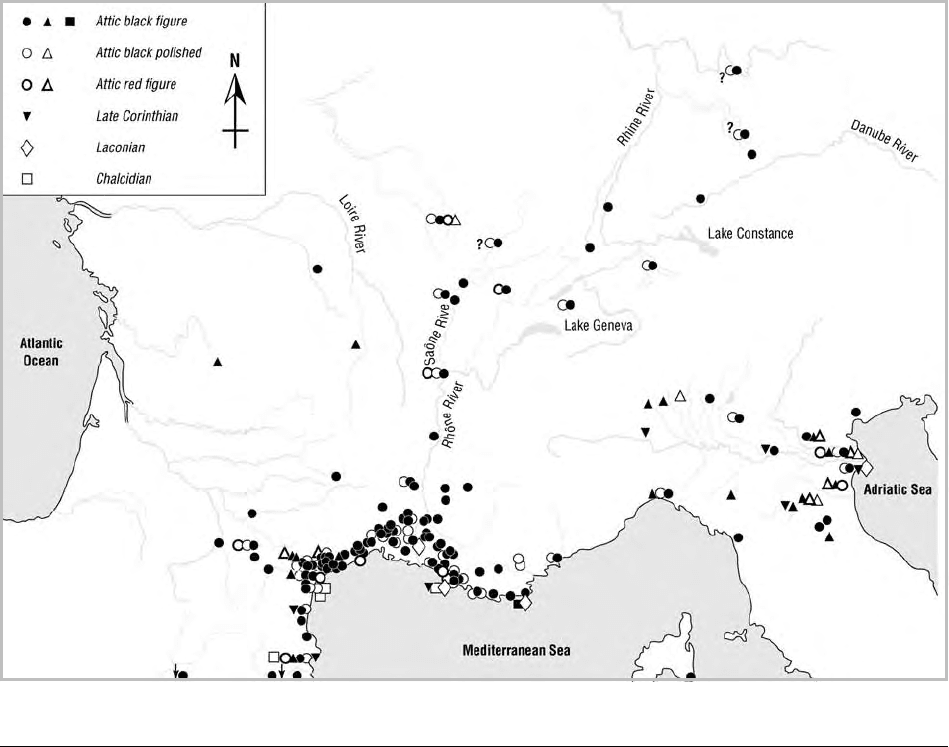

Distribution of Greek pottery of the fourth quarter of the sixth century B.C. (not including east Greek pottery). ADAPTED FROM KIMMIG

2000.

problem of its harbor silting up with riverborne sed-

iments.

Excavations in modern Marseille have yielded

abundant evidence of the Greek town, though ar-

chaeologists are limited in their investigations by

the modern city that overlies the ancient Greek one.

For well over a century archaeologists have noted

large quantities of ancient architectural remains,

pottery from Athens and elsewhere in the Greek

world, coins, and other materials from the early set-

tlement. Since the 1960s archaeologists have been

able to carry out systematic excavations in parts of

the harbor and in places under construction within

the ancient town itself. In the harbor they have dis-

covered at least nine ships from the first century of

the port’s existence as well as warehouses and docks

that formed parts of the harbor’s infrastructure.

Study of archaeological remains within the city of

Marseille indicates that this Greek town of the sixth

century

B.C. covered some 40 hectares of the hilly

land around the harbor and that the town was pro-

tected on its northern edge by a massive stone and

brick wall.

MASSALIA’S REGION AND

DAUGHTER TOWNS

Massalia grew in size and influence and became the

principal center along the southern coast of France,

from Barcelona to Nice. It dominated an extensive

landscape on both sides of the lower Rhône and had

an important impact far inland, north and east of the

headwaters of the Rhône in the interior of the Con-

tinent. French archaeologists have investigated

many settlement and cemetery sites in the lower

Rhône region northwest of Marseille and found ex-

tensive evidence of interaction with the Greek town.

Particularly abundant are sherds of ceramic am-

phorae that had been used to transport wine. Some

GREEK COLONIES IN THE WEST

ANCIENT EUROPE

199