Bogucki P., Crabtree P. Ancient Europe 8000 B.C.-A.D. 1000: Encyclopedia of the Barbarian World. Volume 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

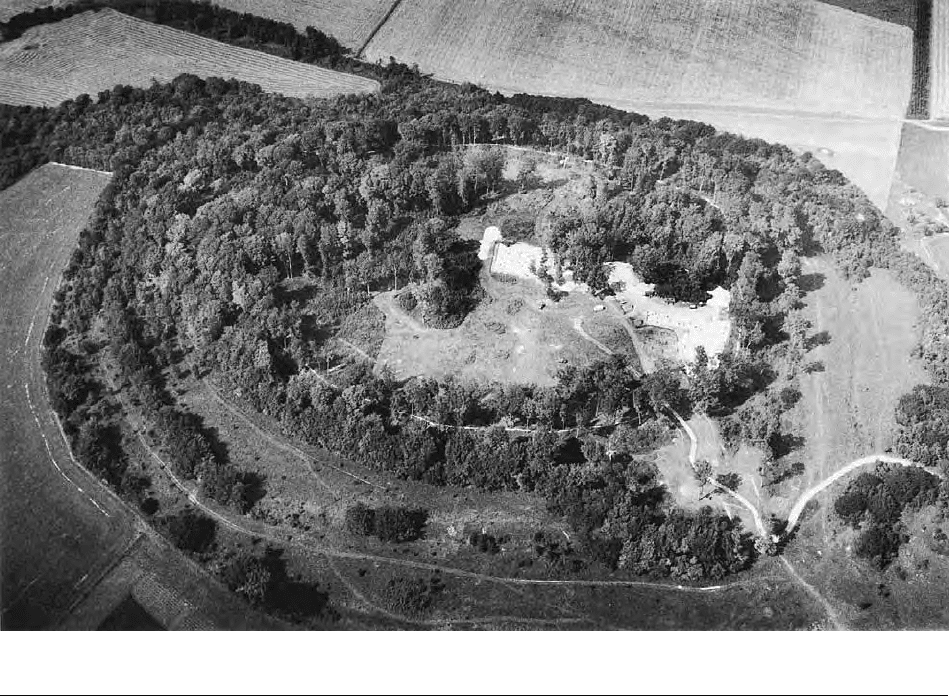

Fig. 1. Aerial of Danebury showing the 1978 excavations in progess. PHOTOGRAPH BY BARRY CUNLIFFE. COURTESY OF THE DANEBURY

TRUST. REPRODUCED BY PERMISSION.

dates to the Late Bronze Age (c. 1000–700 B.C.);

it is joined by a linear earthwork boundary that has

been traced eastward for several miles toward the

valley of the River Itchen.

Excavations at Danebury began in 1969 and

continued annually until 1988. During the twenty

seasons of work the entrances were examined, the

earthwork circuits were sectioned, and 57 percent

of the interior of the main fortified area was totally

excavated. This work established that within the

Late Bronze Age enclosure, defined by the outer

earthwork, the first defense, probably a palisaded

enclosure, was erected in the sixth century

B.C. This

first enclosure was replaced a century or so later by

the inner earthwork, built originally as a massive

timber-faced rampart fronted by a deep ditch. At

this stage there were two gates. The earthworks and

gates underwent various phases of modification, the

most significant coming around 300

B.C., when the

rampart was heightened and reconstructed to have

a steeply sloping outer face fronted by a deep V-

sectioned ditch. From the bottom of the ditch to

the top of the rampart measured about 6 meters (20

feet). At this stage the southwest entrance was

blocked, and the east entrance began to be massive-

ly extended. In this later stage of its life the hillfort

was intensively occupied. The end came some time

in the first half of the first century

B.C., when the

gate was destroyed by fire, and there is some evi-

dence to suggest the slaughter of the inhabitants.

After this the enclosure continued to be used for an-

other fifty years or so, but activity was at a low level

and may have been linked to the continued use of

a temple complex in the center of the old settle-

ment.

Throughout its life from c. 500 to c. 50

B.C. the

hillfort was occupied. From an early stage a system

of roads was established with a main axial street run-

ning between the two gates. Even after the south-

west gate was blocked the street remained the main

axis. Other streets branched out from just inside the

main entrance and ran roughly concentrically

6: THE EUROPEAN IRON AGE, C. 800 B.C.– A.D. 400

230

ANCIENT EUROPE

around the crest of the hill. Amid the streets were

arranged circular houses, rectangular post-built

storage buildings, and a large number of storage

pits. Toward the center of the site, occupying a

prominent position directly visible from the en-

trance, was a cluster of rectangular buildings that

were probably the main shrines of the settlement.

There is, throughout the occupation, a sense of

order in the layout of the various buildings and ac-

tivities. In the early stage, when both gates were in

use, the main occupation zone lay to the south of

the main street, whereas the area to the north was

used mainly for storage. After the southwest gate

was blocked the order was reversed, suggesting that

a major conceptual change had taken place.

In the last two centuries or so of the settle-

ment’s life a rigorous order seems to have been im-

posed. The rows of four- and six-post storage build-

ings arranged along the streets were rebuilt many

times over on the same plots, whereas immediately

behind the ramparts—where the stratigraphical evi-

dence is particularly well preserved and the circular

houses cluster—it is possible to distinguish six

major phases of rebuilding. In this area individual

building plots can be distinguished. Although each

had a different structural history, their discrete spa-

tial identities were maintained, suggesting continu-

ity of ownership over a long period of time. Ar-

rangements of this kind indicate a high level of

centralized control.

The most frequently occurring structures with-

in the fort were storage pits, of which more than

one thousand have been examined. For the most

part they were probably used for the storage of seed

grain in the period between harvest and the next

sowing. Experiments have shown that, so long as

the pits were properly sealed and airtight, the seed

remained fresh and fertile. Evidence from many of

the pits indicates that propitiatory offerings were

made once the grain was removed, presumably to

thank the chthonic (earth) deities for protecting the

seed and in anticipation of a fruitful harvest. The of-

ferings vary but include sets of tools, pots, animals

complete or in part, and human remains.

Activities carried out within the fort included

ironsmithing, bronze casting, carpentry, wattle

work and basketry, the weaving and spinning of

wool, and the milling of grain. Additional evidence

points to the existence of complex exchange systems

involving the importation and redistribution of

goods, including salt from the seacoast, iron ingots,

and shale bracelets. The presence of a large number

of carefully made stone weights is clear evidence

that a system of careful measurement was in opera-

tion. In all probability the hillfort, in its developed

state, was a place where the central functions of re-

distribution were carried out to serve people living

in a much wider territory.

The excavation of a number of Iron Age settle-

ments in the landscape around Danebury showed

that, although a number of farms existed during the

early phase of the fort’s existence, after the major re-

construction c. 300

B.C. farmsteads for some dis-

tance around were abandoned. This coincides with

an increase in the density and intensity of occupa-

tion within the fort, the implication being that the

rural population coalesced within the defenses. Al-

though this may have been a response to a period

of unrest, it could equally be explained as a feature

of socioeconomic change resulting in a greater de-

gree of centralization.

See also Hillforts (vol. 2, part 6).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cunliffe, Barry. Danebury Hillfort. Stroud, U.K.: Tempus,

2003.

———. Danebury: An Iron Age Hillfort in Hampshire. Vol.

6, A Hillfort Community in Perspective. Council for

British Archaeology Research Report 102. London:

Council for British Archaeology Research, 1995.

B

ARRY CUNLIFFE

DANEBURY

ANCIENT EUROPE

231

THE EUROPEAN IRON AGE, C. 800 B.C.– A.D. 400

IRON AGE IRELAND

■

FOLLOWED BY FEATURE ESSAY ON:

Irish Royal Sites . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 239

■

Iron Age Ireland suffers from a paucity of sites and

serious dating problems, which makes it difficult to

construct a coherent framework within which to at-

tempt interpretation. Thus, the Iron Age lingers in

the long shadow of medieval Ireland; the abundant

and varied medieval literature and the rich and pro-

lific material culture of the medieval period have

strongly affected the interpretation of Iron Age ar-

chaeology. Increasingly, however, Iron Age archae-

ological research is being generated by archaeolo-

gists, formulated in archaeological terms, and

conducted using an array of archaeological meth-

ods, including aerial photography, geophysical sur-

vey, and underwater and wetland (i.e., peat bog) ex-

ploration. These research agendas do not ignore

medieval textual and archaeological evidence; rath-

er, they reflect increasing confidence that a coherent

framework for Iron Age archaeology can be con-

structed.

CHRONOLOGY

To begin with a note about terminology, “medi-

eval” is used here to distinguish the period from the

fifth century to c. 1500. In Irish writing, archaeolo-

gists normally employ the terms “early Christian”

for the fifth century

A.D. to A.D. 800, “Hiberno-

Norse” or “Viking” for

A.D. 800–1169, and “medi-

eval” starting with the Anglo-Norman invasions of

A.D. 1169–1172. For our purposes, we can think

of the Iron Age in terms of three periods bounded

by the Late Bronze Age, which ended c. 700

B.C.,

and the early Christian period. There is almost no

available data for the Early Iron Age, which spanned

c. 700–300

B.C. The Middle Iron Age, or La Tène

Iron Age, lasted from 300

B.C. into the first century

A.D. It was a time that saw major construction at

many sites and the appearance and development of

La Tène art, which flourished into the early Chris-

tian period. In the Late Iron Age, or Roman Iron

Age, contacts with the Roman world, especially

with Britain, began, as indicated by imports of vari-

ous goods. The earliest evidence of writing dates to

this time. The period ends with the first recorded

Christian missions, about

A.D. 431/432.

Archaeologists still depend heavily on conven-

tional dating by stylistic analyses and comparisons,

so this discussion will start there. The closing phase

of the Late Bronze Age, the Dowris phase, ended

c. 700

B.C. The first subsequent datable object is an

imported gold torc (neck ring) from Knock, Coun-

ty Roscommon, decorated in La Tène style and with

close parallels in the Rhineland from c. 300

B.C. A

hoard from Broighter, County Derry, includes a

gold torc with spectacular La Tène decoration,

which is dated approximately by another item in the

same collection, a gold necklace of Mediterranean

232

ANCIENT EUROPE

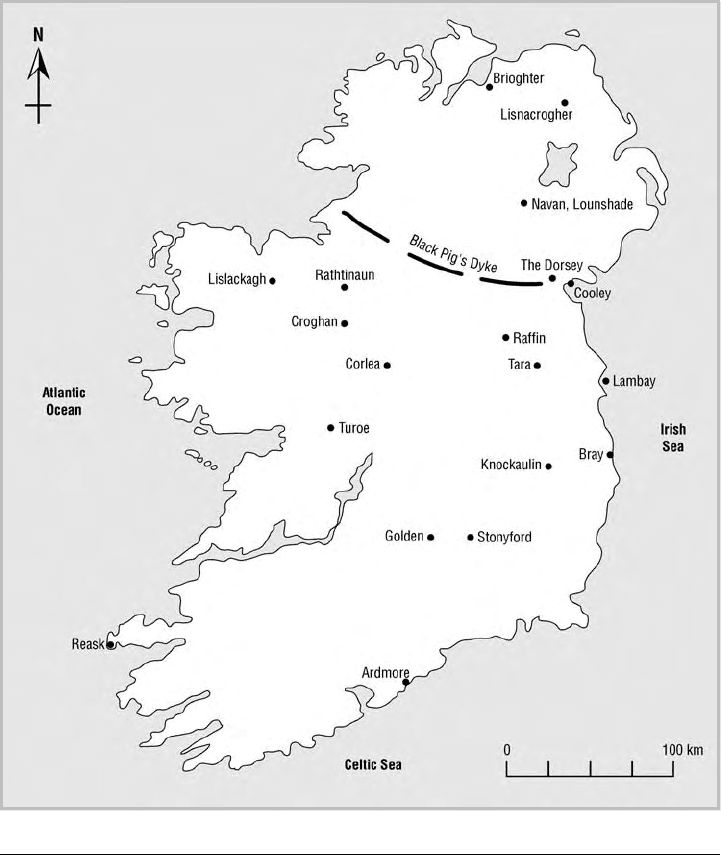

Selected sites in Iron Age Ireland.

origin from the first century B.C. or the first century

A.D. As the Roman Empire expanded into Gaul (in

the mid-first century

B.C.) and Britain (in mid-first

century

A.D.), increasing contact with the Roman

world resulted in the appearance in Ireland of well-

dated Roman goods, such as coins and pottery.

Coins are not plentiful, though, and most come

from isolated hoards, unrelated to sites, while

Roman pottery is rare.

Radiocarbon dating has been applied to the

Iron Age, of course, but for much of the period the

tree-ring samples used for calibration show little dif-

ference in amounts of residual radiocarbon over sev-

eral centuries. In consequence, dates are corre-

spondingly imprecise. Fortunately, however, the

dendrochronological sequence for Irish oak makes

it possible to date the felling of a tree accurately,

often to the exact year. The waterlogged conditions

necessary for the survival of wood, which are com-

mon in this region, make this technique applicable

to many Irish archaeological sites. The contrast in

precision between radiocarbon dating and dendro-

chronology is well illustrated at Navan, County Ar-

magh, where the base of a phase 4 central post has

survived. The radiocarbon date for this post is 380–

100

B.C., a range of 280 years. Dendrochronology

provided a felling date for this post of 95

B.C. (or

possibly early 94

B.C.).

IRON AGE IRELAND

ANCIENT EUROPE

233

SITE IDENTIFICATION

There are two major reasons why so few Iron Age

sites are known. The first, paradoxically, is the sheer

number of sites. The issue of ringforts, or raths, is

particularly important here, for there is hot debate

as to whether these enclosed farmsteads are all of

early medieval date or whether some may be of the

Iron Age. Of those that have been excavated and

that can be dated (many cannot), almost all are in-

deed early medieval. There are, however, some thir-

ty thousand ringforts, of which only about 1 percent

have been excavated—hardly a statistically adequate

sample. Moreover, there are other types of circular

sites of the same general size (e.g., henges, ring bar-

rows, and small monasteries) that are easily con-

fused with ringforts unless closely inspected.

The second reason is that field-walking survey

cannot be employed in this context. This method is

put to effective use in many parts of the world and

simply involves walking over plowed land, looking

for scatters of artifacts, typically, potsherds. In Ire-

land, however, a high percentage of farmland is

under pasture, and other large areas are covered by

blanket bog. Moreover, the Iron Age is virtually

aceramic, which means that there is virtually no

chance of finding diagnostic ceramics and little like-

lihood of finding diagnostic metal artifacts.

EARLY IRON AGE (C. 700–300

B.C.

)

Hardly any artifacts can been attributed to this peri-

od, and only two sites merit discussion. The first is

the crannog of Rathtinaun, County Sligo, where ex-

cavation showed a two-phase occupation. Phase 1

contained only Late Bronze Age Dowris-type arti-

facts, but phase 2 held both Dowris-type artifacts

and a few iron objects. Rathtinaun, then, appears to

bridge the Bronze Age and Iron Age and should

date to the eighth to seventh centuries

B.C. Radio-

carbon dates, however, indicate that the site was oc-

cupied no earlier than the fifth through second cen-

turies

B.C.

Second, there is site B at Navan. As at Rath-

tinaun, phase 3 artifacts were from the Dowris

phase, with only a few small iron objects. Phase 3 ra-

diocarbon dates, however, range from the fourth

century

B.C. into early A.D. times; since the end of

phase 3 was followed immediately by phase 4, dated

precisely to 95

B.C. (from dendrochronology), it is

virtually certain that phase 3 lasted until about 100

B.C. The problems posed by these two sites cannot

be resolved at present and so, by the same token, the

Early Iron Age remains singularly elusive.

MIDDLE IRON AGE (C. 300

B.C.

TO C.

A.D.

100)

The date of c. 300 B.C. for the start of this period

is based, as noted, on the first appearance of the La

Tène art style. Nearly all the Iron Age La Tène dec-

orated objects in Ireland are found on the northern

half of the island. The development of La Tène art

in this area owes much to close contacts with Wales

and northern Britain, just across the Irish Sea. Irish

craft workers, however, were not mere imitators, for

they produced their own variations of British types

as well as some artifact styles unique to Ireland, such

as Y-shaped objects, Monasterevin disks, Petrie and

Cork crowns, and the so-called latchets. As else-

where in Europe, La Tène art was displayed mainly

on high-status personal metalwork. There are also

numerous bronze horse bits, several in pairs, sug-

gesting that the two-horse chariots so well known

from Iron Age Britain and the Continent were used

in Ireland as well. Some of the enigmatic Y-shaped

pieces also occur in pairs and may be components

of chariot harnessing. Iron spearheads are known, as

are fine bronze spear butts.

To judge by several beautifully decorated

bronze scabbards, however, swords were the war-

riors’ pride. Stylistically, they derive from Continen-

tal swords of the third through second centuries

B.C.

The Irish ones are much shorter—the blades rang-

ing from 37 to 46 centimeters; one wonders how

they could be used, except as long daggers. Of all

the scabbards and swords, only one sword comes

from a securely dated context—the excavation at

Knockaulin, probably from the first century

B.C. or

first century

A.D.

Although most of La Tène art finds expression

on metal items of personal equipment or adorn-

ment, there are five La Tène decorated stones; the

one at Turoe, County Galway (fig. 1), is embel-

lished most adeptly. There are also numerous

querns (grindstones) with La Tène decoration.

Many carved stone heads are attributed to the Iron

Age, but they bear only the vaguest stylistic resem-

blance to Iron Age human representations else-

where.

6: THE EUROPEAN IRON AGE, C. 800 B.C.– A.D. 400

234

ANCIENT EUROPE

Almost all decorated metalwork has been dis-

covered accidentally, much of it taken from bogs

and lakes. The practice of votive deposits also is

known in Britain and on the Continent. In those

places, decorated metalwork also appears in burials,

however, providing good associations and dating

evidence. In Ireland few burials contain such arti-

facts, and they are virtually absent from the few ex-

cavated sites, which makes it doubly difficult to date

them or to relate them to other aspects of Iron Age

life (and death).

The major sites of the Middle Iron Age are the

so-called royal sites. Their commanding locations

and large sizes imply that they were the most impor-

tant sites of the Middle Iron Age, dominating ritual

and ceremonial life over considerable areas. Despite

their prominence, they have yielded no deposits of

high-status valuables. Such items seem to have been

reserved for watery places. Significantly, four bronze

trumpets with La Tène decoration (and, reportedly,

human skulls) were found in the nineteenth century

in Loughnashade, a small lake just below Navan.

One remarkable exotic import was discovered in a

late phase 3 context at Navan (site B), however.

This was the skull of a Barbary ape (with a radiocar-

bon date of 390–20

B.C.), which certainly had trav-

eled a very long way from its homeland in north-

western Africa.

The Dorsey, County Armagh, is a very large, ir-

regular enclosure about 30 kilometers south of

Navan. Parts of it run across bog, which preserved

timbers from its construction. Dendrochronologi-

cal dates from these timbers show two phases of

building, the first between 159 and 126

B.C. and the

second between 104 and 86

B.C. The Dorsey lies

close to a section of the Black Pig’s Dyke, a series

of linear earthworks running east to west across Ire-

land. This set of earthworks may have marked the

southern boundary of Iron Age Ulster, for one sec-

tion of the dyke is dated by radiocarbon to 390–70

B.C. Other linear earthworks in Ireland may be of

the Iron Age also, but none are dated. Trackways

constructed across bogland have been dated to the

Iron Age by dendrochronology. The best known of

these is Corlea, County Longford, where excavation

uncovered two stretches of road over 2 kilometers

long, with dates of 156 ± 9

B.C. and 148 B.C. Con-

struction required two hundred to three hundred

mature oak trees, besides other species.

Fig. 1. Turoe Stone, County Galway, Ireland. A superb

example of La Tène art on a granite boulder. COURTESY OF

BERNARD WAILES. REPRODUCED BY PERMISSION.

Hillforts are a prominent feature of Iron Age

landscapes over much of western Europe, so the

sixty to eighty hillforts in Ireland conventionally

have been assigned to this period. Of the few exca-

vated so far, however, most appear to be Late

Bronze Age rather than Iron Age. Moreover, they

are very diverse in size and form. Some are so com-

pact that they could be seen as substantial ringforts

or cashels on hilltops, some are large and rambling

in plan, and some have ramparts so small (as little

as 1 meter high) that probably they were not forts

at all. Whether there are really Iron Age hillforts in

Ireland is moot. Of the estimated 250 known coast-

al promontory forts, a few have been excavated, but

only Dunbeg, County Kerry, has any dating evi-

dence—a radiocarbon date from the first few centu-

ries

A.D., probably Late Iron Age or even early me-

dieval, rather than Middle Iron Age.

IRON AGE IRELAND

ANCIENT EUROPE

235

Residential sites are very scanty indeed. One site

under a ringfort at Feerwore, County Galway, pro-

duced a few artifacts for which dating to the second

to first century

B.C. has been suggested. Two coastal

shell-midden sites have radiocarbon dates placing

them in the Middle Iron Age, as do two crannogs

at Lough Gara, County Sligo. There is one small

ringfort known for the period, at Lislackagh, Coun-

ty Mayo, where internal circular structures were ra-

diocarbon dated to 200

B.C. to A.D. 140. A handful

of other sites have dates overlapping both the Mid-

dle and Late Iron Ages. Despite the limited evi-

dence for daily life in the Middle Iron Age, it is clear

that major constructions were undertaken, which

implies the mobilization of substantial groups of

skilled labor. Particularly noteworthy is the practi-

cally simultaneous construction of phase 4 at Navan

(95

B.C.) and the later phase of building at the Dor-

sey (104–86

B.C.). The proximity of these two sites

suggests that one authority might have directed

construction at both.

LATE IRON AGE (C.

A.D.

100 TO

C. 550

A.D.

)

There is no obvious demarcation between the Mid-

dle and Late Iron Ages. Roman material began to

appear during the first century

A.D., possibly as early

as the first century

B.C. It is not until the late first

century

A.D., however, that evidence appears of

close (though not necessarily intense) contact with

the Roman world, so an arbitrary date of c.

A.D. 100

seems suitable. The main issue for consideration is

the extent to which interaction with the Roman

world promoted changes in Irish society.

J. Donal Bateson has reviewed Roman materials

in Ireland in detail, and the total is surprisingly

small, considering Ireland’s proximity to Roman

Britain and Gaul. Clearly, Roman goods were not

reaching Ireland in anything like the quantities that

reached, say, Germany and the southern Baltic dur-

ing the same period. Roman imports into Ireland

fall into two chronological groups, the first through

second centuries and the fourth through fifth centu-

ries. There is very little third-century Roman mate-

rial, perhaps reflecting the widespread economic

contraction of the period, demonstrated, for exam-

ple, by the contraction of trade from the Continent

to Britain. The material in the earlier category con-

sists mainly of coins and fibulae (brooches) and very

small amounts of Gaulish Samian (terra sigillata)

pottery. The objects in this group and their contexts

are reasonably consistent with trade and small-scale

contacts. The later group, of the fourth through

fifth centuries, also includes coins but has significant

quantities of silver in the form of ingots and hack-

silver (silver artifacts cut into pieces). These items

look suspiciously like the result of successful raiding,

and we know from Roman sources of this period

that the Irish (or Scotti) participated in the frequent

barbarian raids on Roman Britain.

There are a very few burials in Roman style. A

cremation in a glass container at Stonyford, County

Kilkenny, from the first or early second century

A.D.,

and an inhumation cemetery at Bray, County Wick-

low, from the second century

A.D. both show famil-

iarity with Roman burial practices of the time. Pre-

sumably, these are the burials of either Roman

immigrants or emigrants returned from the Roman

world. Grave goods from the small inhumation

cemetery on Lambay Island, County Dublin, show

close affinities with items from northern Britain in

the late first century

A.D., and the people may have

been British refugees from the Roman conquest.

Inhumation burial with the body extended appears

to have become increasingly common through the

Late Iron Age, and some such burials are in long

cists (graves lined with stone slabs). Because extend-

ed inhumation burial began to replace cremation

from about the second century

A.D. in the Roman

Empire, the same shift in Ireland may reflect Roman

practice. Dating Irish burials is seriously hampered

by the general lack of grave goods, however.

Two other disparate examples of Roman con-

tact come from Golden, County Tipperary, and

Lough Lene, County Westmeath. At Golden there

was a small Roman oculist’s stamp of slate, inscribed

along one edge, and at Lough Lene part of a flat-

bottomed boat of Mediterranean construction was

found. It is assumed to be of Roman date, although

its radiocarbon date is 300–100

B.C. (This, of

course, dates the growth of the wood and not nec-

essarily the boat’s construction.)

There are few remains of residential sites from

the Late Iron Age. Traces of occupation from be-

neath two ringforts have been radiocarbon dated to

the third through seventh centuries

A.D., whereas

dates from several structures on Mount Knock-

narea, County Sligo, range from the first century

6: THE EUROPEAN IRON AGE, C. 800 B.C.– A.D. 400

236

ANCIENT EUROPE

B.C. to the seventh century A.D. A sherd of Gaulish

terra sigillata pottery of the first century

A.D. was

plowed up at the large coastal promontory fort of

Drumanagh, County Dublin. This find has fueled

suggestions that this site may have been a trading

station, and the proximity of Lambay Island, with

its cemetery of possible British refugees, lends cre-

dence to the theory.

At Tara, County Meath, the Rath of the Synods

has yielded intriguing evidence. The finds suggest

that the site had four phases of occupation: the first

and third were small cemeteries, while the second

and fourth were probably residential. Artifacts in-

cluded some items of Gaulish terra sigillata of the

first to second centuries

A.D., a lead seal, glass beads,

and iron padlocks. All the datable objects fall within

the first to fifth centuries

A.D. It is striking that al-

though several objects certainly or probably are im-

ports from the Roman world, none are definitely of

Irish manufacture. This, then, is the most “Roman”

site known in Ireland, but it assuredly does not con-

form to any type of actual Roman site. The location

of the Rath of the Synods at a royal site must surely

be significant, but how this site should be interpret-

ed is unclear.

Toward the end of the Late Iron Age, perhaps

in the fourth century

A.D., the first indications of na-

tive Irish literacy appear in the form of ogham in-

scriptions, in which letters of the alphabet are de-

noted by different combinations of vertical or

oblique strokes. The model for an alphabetic script

presumably was Roman, and its employment on

memorial stones also echoes Roman usage. There is

no space here to debate the vexed issue of when

the Irish language first entered Ireland, but these

ogham inscriptions are the earliest written evidence

for the language. The script also demonstrates the

presence of Irish settlers in western Britain, where

ogham inscriptions (many duplicated in Latin) date

to the fifth and sixth centuries, particularly in Wales

and southwestern Britain.

DISCUSSION

The picture of Iron Age Ireland sketched here is one

dominated by a welter of unassociated objects from

chance discoveries, which can be organized into a

somewhat murky picture only with difficulty. It is

striking that the only really coherent archaeological

evidence of Iron Age Ireland comes from larger-

scale excavations, such as those of wetland areas and

royal sites. Even so, it is still virtually unknown

where and how people lived. It is no wonder that

the abundant historical and archaeological evidence

of early medieval Ireland, highly visible and largely

comprehensible, still casts such a long interpretative

shadow over the Iron Age.

The traditional or “nativist” view sees Iron Age

Ireland essentially as a pagan version of Christian-

ized early medieval Ireland. Thus, the society de-

picted in the medieval law tracts, for example, pro-

vides a template for Iron Age society: the higher

ranks, supported by clients and slaves, lived in ring-

forts, crannogs, and cashels and spent most of their

time planning cattle raids. This view is epitomized

by Kenneth Jackson’s Oldest Irish Tradition: A

Window on the Iron Age, an analysis of the Táin Bó

Cúailnge (“Cattle Raid of Cooley,” the central tale

of the Ulster Cycle of stories). The Táin is an ac-

count of the raid, organized by Queen Medb

(Maeve) of Connacht, to capture the famous brown

bull of Cooley in Ulster. In this epic, war chariots,

druids, single combat between champions, and cat-

tle raiding are prominent. Jackson argued that these

elements of the tale identified a genuine Iron Age

oral epic, eventually written down in the eleventh

century

A.D. Moreover, Medb and her counterpart,

the king of Ulster, lived at identifiable sites—

respectively, Cruachain (Croghan) and Emain

Macha (Navan)—which seems to add authenticity.

The nativist position has come under revisionist

fire from both historians and archaeologists. Fur-

ther textual analysis of the Ulster Cycle shows that

it was largely a medieval composition by writers fa-

miliar with Latin literature, Greek epics, the Scrip-

tures, and writings of the early church fathers. Simi-

larly, increasingly fine-grained analyses of the

aforementioned law tracts show that they were al-

most certainly composed by monks with a Christian

agenda, rather than by secular scholars perpetuating

traditional pre-Christian law. The excavation of two

of the royal sites since Jackson’s work was published

shows that there are no satisfactory grounds for re-

garding them as the royal residences portrayed in

the Táin. More specifically, Mallory has pointed out

that the swords described in the Táin were long, re-

sembling medieval swords not the very short swords

of Iron Age Ireland.

IRON AGE IRELAND

ANCIENT EUROPE

237

The revisionists contend that the country un-

derwent a major transformation through the centu-

ries of contact with Rome, culminating in conver-

sion to Christianity and the consequent intro-

duction of literacy. In this scenario the Iron Age is

seen as a depressed period when agricultural and

pasture lands contracted, as shown by an increase of

tree pollen in several pollen diagrams from different

parts of Ireland. This contraction began in about

the seventh century

B.C., perhaps intensified around

200

B.C., and continued until about the third centu-

ry

A.D., when woodland clearance recommenced.

This renewed clearance has been attributed to the

introduction of the plow with iron share and coulter

and of dairying, through contact with Roman Brit-

ain. It is thought that productivity of both tillage

and livestock thus improved considerably, which in-

creased the wealth of the upper classes and enabled

them to invest in clients and to buy slaves. In this

way, so the hypothesis has it, the rural economy and

society that were so well documented in the early

medieval period were triggered by innovations from

the Roman world.

We have no satisfactory dating for the appear-

ance of the iron share and coulter, however, and the

introduction of dairying is the subject of controver-

sy. Pam Crabtree has argued that the mortality pat-

tern of cattle bones from Knockaulin, probably dat-

ing to the first century

B.C. or the first century A.D.,

is consistent with dairying. Finbar McCormick dis-

puted this analysis and went on to propose the hy-

pothesis that dairying was introduced through

Roman contacts (i.e., later than the Knockaulin as-

semblage). In addition, he argued that ringforts—

those typical enclosed homesteads of the earlier me-

dieval period—were developed specifically to pro-

vide protection for valuable dairy cattle. Milk

residues have been identified, however, in British

prehistoric pottery. Since this pottery is as old as the

Neolithic (fourth through third millennia

B.C.), it is

plausible to propose that dairying was introduced to

nearby Ireland in prehistoric times. Clearly, this de-

bate will continue.

The nativist and revisionist positions are not

completely incompatible: the former does not deny

that the conversion to Christianity promoted sub-

stantial changes in Irish society, nor does the latter

deny some continuity from Iron Age to early Chris-

tian Ireland (e.g., La Tène art). As archaeological

evidence gradually accrues, and textual analysis is

pursued, interpretations will improve.

See also Milk, Wool, and Traction: Secondary Animal

Products (vol. 1, part 4); Trackways and Dugouts

(vol. 1, part 4); Bronze Age Britain and Ireland

(vol. 2, part 5); Irish Bronze Age Goldwork (vol. 2,

part 5); La Tène Art (vol. 2, part 6); Irish Royal

Sites (vol. 2, part 6); Early Christian Ireland (vol. 2,

part 7); Raths, Crannogs, and Cashels (vol. 2, part

7).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bateson, J. Donal. “Further Finds of Roman Material from

Ireland.” Colloquium on Hiberno-Roman Relations

and Material Remains. Proceedings of the Royal Irish

Academy 76C (1976): 171–180.

———. “Roman Material from Ireland: A Reconsidera-

tion.” Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy 73C

(1973): 21–97.

Copley, M. S., R. Berstan, S. N. Dudd et al. “Direct Chemi-

cal Evidence for Widespread Dairying in Prehistoric

Britain.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Science

100, no. 4 (February 18, 2003): 1524–1529.

Crabtree, Pam. “Subsistence and Ritual: The Faunal Re-

mains from Dún Ailinne, Co. Kildare, Ireland.”

Emania 7 (1990): 22–25.

Fredengren, Christina. “Iron Age Crannogs in Lough

Gara.” Archaeology Ireland 14, no. 2 (2000): 26–28.

Jackson, Kenneth H. The Oldest Irish Tradition: A Window

on the Iron Age. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge Univer-

sity Press, 1964.

Kelly, Fergus. A Guide to Early Irish Law. Early Irish Law

Series, no. 3. Dublin, Ireland: Dublin Institute for Ad-

vanced Studies, 1988.

McCone, Kim. Pagan Past and Christian Present in Early

Irish Literature. Maynooth Monographs, no. 3. May-

nooth, Ireland: An Sagart, 1990.

McCormick, Finbar. “Cows, Ringforts, and the Origins of

Early Christian Ireland.” Emania 13 (1995): 33–37.

———. “Evidence of Dairying at Dún Ailinne?” Emania 8

(1991): 57–59.

McManus, Damian. A Guide to Ogam. Maynooth Mono-

graphs, no. 4. Maynooth, Ireland: An Sagart, 1991.

Mallory, James P. “The World of Cú Chulainn: The Archae-

ology of Táin Bó Cúailgne.” In Aspects of the Táin. Ed-

ited by James P. Mallory, pp. 103–159. Belfast, North-

ern Ireland: December Publications, 1992.

———. “The Sword of the Ulster Cycle.” In Studies on

Early Ireland: Essays in Honour of M. V. Duignan. Ed-

ited by Brian G. Scott, pp. 99–114. Dublin, Ireland: As-

sociation of Young Irish Archaeologists, 1981.

6: THE EUROPEAN IRON AGE, C. 800 B.C.– A.D. 400

238

ANCIENT EUROPE

Megaw, M. Ruth, and J. V. S. Megaw. Celtic Art: From Its

Beginnings to the Book of Kells. Rev. ed. New York:

Thames and Hudson, 2001.

Mitchell, Frank, and Michael Ryan. Reading the Irish Land-

scape. 3d ed. Dublin, Ireland: Town House, 1997.

Raftery, Barry. Pagan Celtic Ireland: The Enigma of the Irish

Iron Age. London: Thames and Hudson, 1994.

Thomas, Charles. Celtic Britain. London: Thames and

Hudson, 1986.

Waddell, John. The Prehistoric Archaeology of Ireland. Gal-

way, Ireland: Galway University Press, 1998.

B

ERNARD WAILES

■

IRISH ROYAL SITES

The Irish “royal sites” are so called because medi-

eval Irish scholars believed them to have been the

capitals of pre-Christian high kings of four of the

five ancient provinces of Ireland. Croghan

(Cruachain) was the royal site of Connacht, Navan

(Emain Macha) of Ulster, Tara (Temair) of Meath,

and Knockaulin (Ailenn, Dún Ailinne) of Leinster.

No early source identifies a royal site for Munster.

Various medieval texts refer to the royal sites as for-

mer royal residences and burial grounds; venues for

major assemblies, including the inauguration of

kings; and centers of pagan ritual. Although these

sites were invoked as symbols of kingship in medi-

eval Ireland, there is no evidence that they actually

were used during the Middle Ages, and the retro-

spective nature of medieval references to these sites

demands caution in assessing their original func-

tions or significance. Archaeology can provide a

firmer understanding, and Knockaulin, one of the

two extensively excavated sites (with Navan), can

serve as an exemplar.

At Knockaulin an oval earthwork encloses c. 13

hectares, with the entrance on the east side of the

site. Despite the hilltop location, it was not a defen-

sive site, for the bank is outside the ditch. Geophysi-

cal survey showed substantial anomalies only

around the center of the site, where subsequent ex-

cavation produced the following (simplified) se-

quence:

Flame (latest): Low mound of burned material,

including many animal bones, which sug-

gests periodic feasting

Dun: Central tower and circle of posts disman-

tled; stone slabs and earth laid over the re-

stricted area of Emerald-phase burning

Emerald: Perimeter wall of Mauve phase dis-

mantled, but central tower and inner circle

of posts left standing, despite intense local-

ized burning

Mauve: Double-walled, circular timber struc-

ture, c. 42 meters in diameter, enclosing a

circle, 25 meters in diameter, of freestand-

ing posts and, at the center, a heavily built

timber structure, c. 6 meters in diameter

and with buttresses, that may have been a

wooden tower

Rose: Figure-eight, triple-walled timber struc-

ture with a larger circle, c. 35 meters in di-

ameter, and an elaborate, funnel-shaped en-

tranceway; structure dismantled to make

way for Mauve structures

White: Circular, single-walled timber structure,

c. 22 meters in diameter; dismantled to

make way for Rose structures

Tan (earliest): Neolithic trench and artifacts

(fourth millennium through third millenni-

um

B.C.)

None of the Iron Age structures (White

through Mauve) show evidence of residential or fu-

nerary use and must be interpreted as ritual or cere-

monial in nature. The White, Rose, and Mauve en-

trances are oriented toward sunrise around 1 May,

the festival of Beltane, the beginning of summer.

Radiocarbon dates (Rose through Flame) cluster

between the third century

B.C. and fourth century

A.D., while stylistic parallels for metalwork are main-

ly of the first century

B.C. to the first century A.D. An

8-meter-wide roadway runs through the site en-

trance toward the timber structures at the center of

the site. A radiocarbon sample from sod buried be-

neath one of the banks at the site entrance suggests

that bank construction took place in the fifth centu-

ry

B.C.

The other royal sites share several characteristics

with Knockaulin. First, all are on prominent elevat-

ed locations with commanding views. Second, all

have large enclosures. Those at Navan (c. 5 hect-

ares) and the Ráith na Ríg (Rath of the Kings; c. 6

hectares) at Tara both have internal ditches and ex-

ternal banks. Geophysical survey at Croghan shows

a circular anomaly enclosing nearly 11 hectares,

IRISH ROYAL SITES

ANCIENT EUROPE

239