Bulmer-Thomas V., Coatsworth J., Cortes-Conde R. The Cambridge Economic History of Latin America: Volume 2, The Long Twentieth Century

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c14BCB929-Bulmer 052181290 9 October 6, 2005 14:6

632 Miguel Sz

´

ekely and Andr

´

es Montes

1

1.1

1.2

1.3

1.4

1.5

1.6

1.7

Relative Log Wage

1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998

Higher education

relative to primary

Higher education

relative to secondary

Secondary relative

to primary

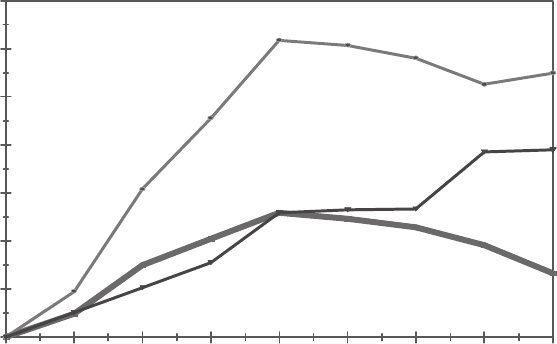

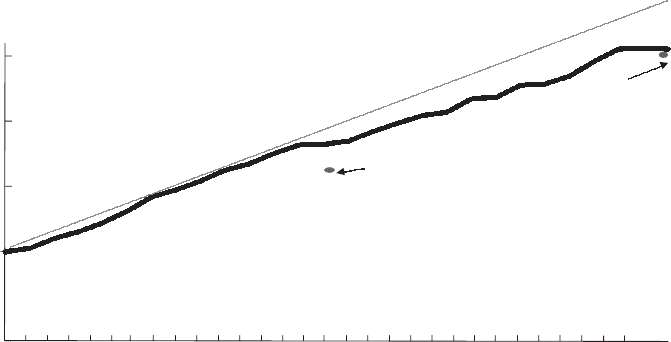

Figure 14.13.Wage differentials in Latin America in the 1990s.

Source: Jere Behrman, Suzanne Duryea, and Miguel Sz

´

ekely, “Schooling Investments

and Aggregate Conditions: A Household-Survey Approach for Latin America and the

Caribbean.”

differential shows a similar pattern, while the secondary-to-primary gap

increased during the first five years of the decade and decreased during the

second half.

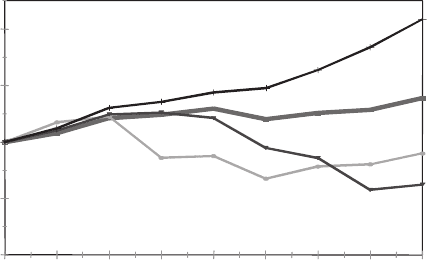

Figure 14.14 summarizes the country-year information for the marginal

return to each level of schooling for the years between 1990 and 1998 (pro-

files normalized to the value of the coefficient for 1990).

29

The generally

positive slope for the linear return reflects the fact that the return to an

extra year of schooling in Latin America has increased by about 7 percent

during the 1990s. The disaggregation by schooling levels reveals that the

increase is totally driven by the large rise in the marginal return to higher

(post-secondary) schooling. The returns to primary and secondary school-

ing declined after the early 1990s, though with partial recovery in the late

1990s.

Table 14.11 provides some evidence on the returns to education by coun-

try.

30

According to the table, having incomplete primary schooling implies,

29

The estimates are the regional average for the returns to schooling from log-wage regressions for each

household survey.

30

The table shows the coefficients of a standard Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) Mincer regression

where the dependent variable is the log hourly wage of each individual and the independent variables

are experience (proxied by age six minus years of schooling), experience squared, and a vector of

dummies representing five different education levels. The returns on education are determined

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c14BCB929-Bulmer 052181290 9 October 6, 2005 14:6

Poverty and Inequality 633

0.8

0.9

1

1.1

1.2

Marginal Return to Completing a Cycle

1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998

Higher

Primary

Linear return per year

Secondary

Figure 14.14.Marginal returns to education: Latin America in the 1990s.

Source: Jere Behrman, Nancy Birdsall, and Miguel Sz

´

ekely, “Economic Reform and Wage

Differentials in Latin America” (Working Paper, Inter-American Development Bank,

2000).

on average, an income 18 percent higher than that for people with no school-

ing. Complete primary education yields a return of 37 percent, whereas

incomplete and complete secondary education have returns of 61 percent

and 95 percent, respectively. The greatest returns are observed for higher

education, with 152 percent on average. The largest differences in returns

between the lowest and highest schooling levels are observed in Brazil,

Chile, Colombia, and Mexico.

This evidence illustrates the circularity between asset ownership, use,

and return. The poor have the smallest stocks of human capital. In the

case of females, those with fewer assets tend to use them to a lower extent.

Furthermore, those with the smallest stocks of human capital receive the

lowest rewards not only for having a small stock but also because the returns

are nonlinear and increase with the size of the stock. Finally, because of the

low returns, the poor (especially women) ultimately earn lower rates on

their assets.

returns to physical capital

The return on an asset such as physical capital has many components, a fact

that complicates the analysis. This chapter’s treatment of physical capital

byavariety of factors and are less subject to individual preferences and decisions. The regression is

estimated for adults in the 25–65 age range and does not correct for sample selection biases attributable

to participation. However, the conclusions about the changes in the returns to education and the

differences between low and high schooling levels do not change substantially when corrections for

the bias are attempted.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c14BCB929-Bulmer 052181290 9 October 6, 2005 14:6

Table 14.11. Returns to education in Latin America during the 1990s

Coefficients from ordinary least squares (OLS) regression

Primary Primary Secondary Secondary Higher

Country Year incomplete complete incomplete complete education

Argentina

∗

1996 0.12 0.21 0.34 0.61.03

Bolivia

∗

1990 −0.14 −0.06 0.11 0.21 0.49

1991 −0.14 −0.06 0.11 0.21 0.49

1993 0.09 0.17 0.36 0.66 1.11

1995 0.06 0.16 0.25 0.56 1.13

Brazil 1992 0.12 0.26 0.47 0.84 1.54

1993 0.10.24 0.47 0.82 1.5

1995 0.45 0.82 1.17 1.72 2.5

1996 0.41 0.76 1.13 1.65 2.39

Chile 1990 0.19 0.36 0.66 0.97 1.72

1992 0.20.33 0.61 1.02 1.83

1994 0.27 0.44 0.67 1.11 1.87

1996 0.19 0.38 0.67 1.08 1.92

Colombia 1997 0.19 0.55 0.82 1.28 2.1

Costa Rica 1989 0.22 0.42 0.71.04 1.51

1991 0.11 0.27 0.53 0.84 1.47

1993 0.30.43 0.65 0.88 1.55

1995 0.21 0.37 0.57 0.84 1.44

Dom. Rep. 1996 0.30.49 0.63 0.75 1.39

Ecuador 1995 0.23 0.49 0.91.26 1.64

El Salvador 1995 0.26 0.49 0.73 1.17 1.77

Honduras 1992 0.15 0.38 0.71 1.11 1.82

1996 0.24 0.54 0.71.23 1.9

1998 0.17 0.40.59 1.79 1.92

Mexico 1989 0.33 0.68 1.05 1.47 1.9

1992 0.43 0.82 1.27 1.72 2.37

1994 0.24 0.52 0.88 1.39 2.05

1996 0.09 0.40.93 1.65 2.43

Nicaragua 1993 0.40.55 0.71 0.99 1.47

Panama 1991 −0.07 0.04 0.22 0.47 0.96

1995 0.06 0.14 0.33 0.56 1.09

1997 −0.03 −0.06 0 0.23 0.96

Paraguay 1995 0.32 0.71 1.07 1.63 2.26

Peru 1991 0 −0.02 0.08 0.12 0.31

1994 0.03 0.08 0.27 0.34 0.73

1997 0.22 0.29 0.50.56 1.09

Uruguay

∗

1989 0.03 0.12 0.27 0.32 0.52

1992 0.27 0.51 0.81 0.99 1.47

1995 0.18 0.36 0.73 0.93 1.46

Venezuela 1995 0.35 0.55 0.73 0.98 1.44

1997 0.27 0.43 0.58 0.88 1.59

Average LAC 1997 0.18 0.37 0.61 0.95 1.52

∗

Surveys with urban coverage.

Source: Orazio Attanasio and Miguel Sz

´

ekely, eds., Portrait of the Poor (Washington, DC, 2001).

634

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c14BCB929-Bulmer 052181290 9 October 6, 2005 14:6

Poverty and Inequality 635

-4

-2

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

1967

1969

1971

1973

1975

1977

1979

1981

1983

1985

1987

1989

1991

1993

1995

1997

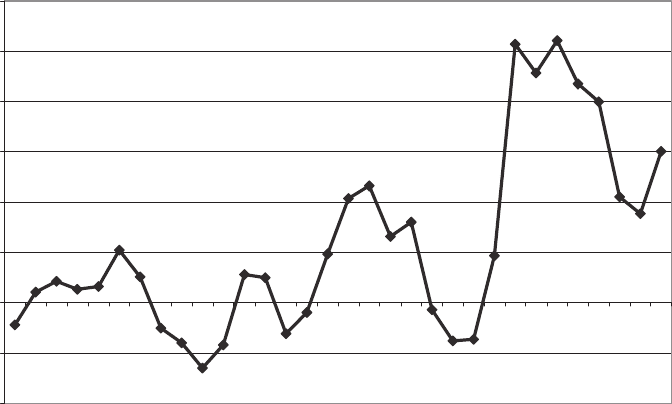

Figure 14.15.Real interest rates for five Latin American countries.

Source: World Bank Global Development Finance & World Development Indicators

(Washington, DC, 2002).

has focused more on its investment component than its infrastructure one.

Because there is no single price that can be used to describe the evolution

of the returns to physical capital investment, this subsection concentrates

on the evolution of interest rates as a general price indicating the behavior

of returns to physical capital, specifically investment.

Figure 14.15 shows the average real interest rate for five Latin American

countries (Brazil, Colombia, Chile, Mexico, and Venezuela) for the period

1965–99.

31

As can be seen, with only few exceptions (eight years out of

the thirty-five spanning the 1965–99 period), real interest rates are posi-

tive and high in many cases. Average real interest rates fluctuated around

1 to 2 percent during the 1960s and early 1970s, were generally low during

the late 1970s, and were positive during practically all the following twenty

years, reaching levels above 10 percent during the mid-1990s. Real interest

rates are a lower-bound indicator of the returns to capital in an economy,

31

Because of the high volatility of real interest rates in most countries, we concentrate only on these

five cases. The data correspond to three-year moving averages for each of the five countries (this is

why the figure plots the data from 1967 on).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c14BCB929-Bulmer 052181290 9 October 6, 2005 14:6

636 Miguel Sz

´

ekely and Andr

´

es Montes

so the data reveal that those owning physical capital assets were most likely

obtaining considerable rewards for putting them to work.

Another way of determining whether returns to capital are attractive in

an international context is the flow of foreign investment to a country.

Presumably, if all other factors remain the same, capital will flow to a

country when its returns (e.g., corrected by risk factors) exceed those that

would be obtained elsewhere. Latin America did attract foreign investment

during the 1990s. This is in stark contrast with the previous two decades,

when hardly any flows took place. The levels of FDI during the 1970s and

1980swere very small because the region was largely closed to capital flows,

but the relatively high levels during the 1990s suggest that returns to capital

in the region were, in fact, attractive.

FACTOR ENDOWMENTS AND

INCOME DISTRIBUTION

The evidence presented in the previous three sections suggests that the

factors underlying the historical persistence of inequality and poverty in

Latin America are the following: (1) income-earning assets in the region have

historically been unevenly distributed among the population; (2) those who

have fewer assets also find fewer opportunities to use these assets to generate

income; and (3) asset returns are lower on a per-unit basis for those with

smaller stocks of assets, so that the poor incur a double financial penalty.

These conclusions may come as a surprise to those arguing that trade

liberalization processes – which have been pursued by most of the countries

in the region since the 1980s–tend to raise the demand for unskilled labor

in unskilled labor-abundant countries such as those in Latin America. This

increased demand is expected, in turn, to reduce inequality and poverty by

boosting the wages for workers with lower schooling levels. Similarly, one

would expect that countries in which physical capital is relatively scarce –

again, as in Latin America – would experience positive capital inflows with

trade openness and capital account liberalization, precisely because of the

initially high returns inherent in a closed economy. This would tend to

reduce the returns to capital, which would ultimately improve income

distribution, given that capital is usually concentrated among the rich.

Under the same argument, if a country that is land-abundant relative to

the rest of the world opens up to trade, the returns on this asset will tend

to increase. The effect on income distribution will depend on how stocks

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c14BCB929-Bulmer 052181290 9 October 6, 2005 14:6

Poverty and Inequality 637

of land are distributed, so for Latin America this would have been expected

to be inequality-increasing.

Why does an apparent contradiction arise between the expected results

from economic liberalization processes in Latin America, on the one hand,

and the empirical evidence presented in the second section on the other?

Is standard trade theory not useful for understanding the current reality in

Latin America? Or is it that perhaps Latin America is not what it seems?

What if, for instance, the region is not as abundant in unskilled labor

as is widely believed? This section develops the argument that the key to

the apparent paradox might be the following: the theory is valid, but the

perceptions are flawed. What seems to be unfounded are the beliefs that the

region has an advantage in producing unskilled labor-intensive goods at low

cost, that capital is significantly scarcer than in the rest of the world, and that

land is a considerably abundant factor. In fact, this section proposes that

Latin America is caught between two worlds. On the one hand, it is not the

most unskilled labor-abundant region. On the other, however, schooling

progress has been so sluggish in the past few decades that the region has

not effected the “big push” observed in other countries (e.g., East Asia) to

reach the point at which comparative advantages in semiskilled labor were

achieved. In a similar vein, capital is certainly not as abundant as in the

most developed economies but, at the same time, it is not as scarce a factor

as in the average developing country. Furthermore, with technical progress,

land does not appear to be as abundant a factor as is commonly supposed.

The region has arrived at this state because at the time that the region’s

endowments were changing, the world was also evolving. Large countries

such as China and India entered the global markets during the 1980s, caus-

ing sizable shifts in the world effective factor endowments. These countries

have a large abundance of relatively unskilled labor, scarce capital, and rel-

atively abundant land. In bringing these factor endowments to the world

market, they have modified the amount of factors of production that are

available on a global scale and, in open competition for world markets,

this has had enormous effects over the prices paid for human and physical

capital in the international arena.

In order to develop this argument, the calculations and estima-

tions by Spilimbergo, Londo

˜

no, and Sz

´

ekely are updated and presented

subsequently.

32

These authors obtain world average values for factor

32

Antonio Spilimbergo, JuanLuis Londo

˜

no, and Miguel Sz

´

ekely, “Income Distribution, Factor Endow-

ments and Trade Openness,” Journal of Development Economics 59 (1997): 77–101.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c14BCB929-Bulmer 052181290 9 October 6, 2005 14:6

638 Miguel Sz

´

ekely and Andr

´

es Montes

endowments by computing each country’s share in world trade and mul-

tiplying this share by the factor endowment (human capital, physical cap-

ital, and land) to obtain a trade-weighted average.

33

The weights are used

because the factor endowments of a country only compete in the world

market if the country actually trades. Therefore, endowments of countries

totally closed to international trade have no weight in the average, whereas

those that do trade are weighted by their importance in international

markets.

34

trade and human capital endowments

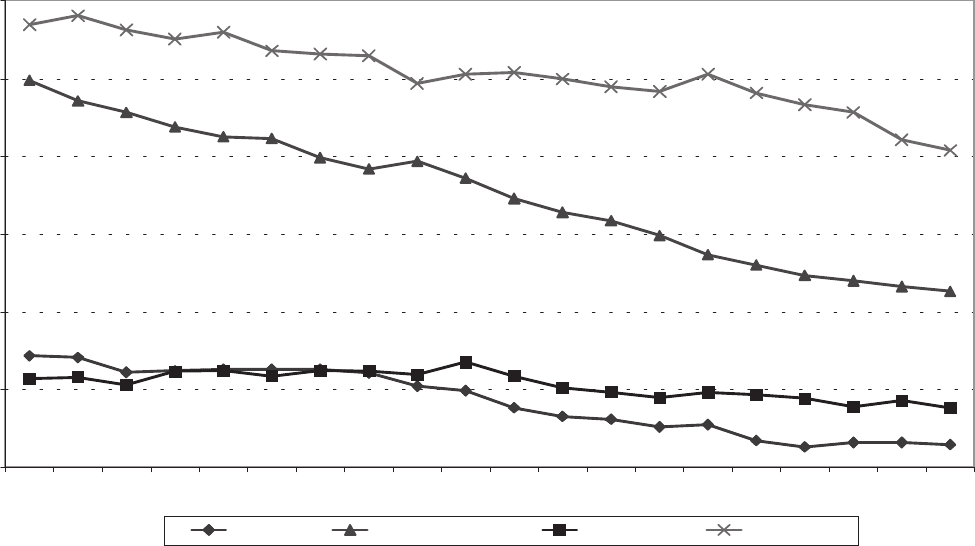

The story of the evolution of human capital is illustrated in Figure 14.16,

which plots the endowment of the most unskilled labor available for pro-

duction – that is, the share of workers with no schooling among the pop-

ulation over twenty-five years of age.

35

As can be seen, Latin America has a

much larger share of working-age population with no schooling than the

East Asian economies or the world average but has a considerably lower

share than South Asia, the most populous region in the world.

33

These authors estimate country and world endowments up to 1992.Here we update the figures to

1996.Weuse the same estimation methods and (updated) data sources as these authors.

34

There are some other studies addressing the trade–inequality relationship. Francois Bourgignon

and C. Morrison, eds., External Trade and Income Distribution (Paris, 1989), develop a model in

which income distribution depends on factor endowments and the degree of trade openness of each

country. By using a cross-country analysis of thirty-six observations in 1970, they conclude that

factor endowments can explain 60 percent of the difference in income shares of the bottom decile

across countries. Sebastian Edwards, “Openness, Trade Liberalization and Growth in Developing

Countries,” Journal of Economic Literature 31 (1997): 1358–93, uses a larger sample of countries with

time-series observations, but does not find any significant effect of trade on income distribution.

There is a larger number of studies addressing the trade–wage inequality relationship. For example,

see Donald Robbins, “HOS Hits Facts: Facts Win: Evidence on Trade and Wages in the Developing

World” (Development Discussion Paper 557,Harvard Institute for International Development,

Harvard University, 1996); Adrian Wood, North-South Trade Employment and Inequality: Changing

Fortunes in a Skill-Driven World, (London, 1994), and “Openness and Wage Inequality in Developing

Countries: The Latin American Challenge to East Asian Conventional Wisdom,” The World Bank

Economic Review (1996); George Borjas and Valerie Ramey, “Foreign Competition, Market Power

and Wage Inequalities,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics XC (1995): 1075–1110; Richard Freeman

and Lawrence Katz, eds., Differences and Changes in Wage Structure (Chicago, 1995). We chose the

methodology by Spilimbergo, Londo

˜

no, and Sz

´

ekely for two reasons. The first is that they use

more adequate trade openness measure and estimation methods, and the second is that rather than

focusing on wage inequality, they consider the distribution of total household income.

35

These figures use the share of adults with no schooling, primary, secondary, and higher education

from the updated Barro-Lee database. See Jong Wha Lee and Robert Barro, “International Data on

Educational Attainment: Updates and Implications,” (Working Paperno.42, Center for International

Development, Harvard University, April 2000)tomeasure the human capital endowment of each

country. East Asia, according to the definition adopted here, comprises the four fastest growing East

Asian countries.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c14BCB929-Bulmer 052181290 9 October 6, 2005 14:6

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982

1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988

1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995

World

Latin Americ

a East

Asia

South Asia

Figure 14.16.P

ercentage of workers with no schooling among the population over tw

enty-five years of age by region.

Source:

Authors’ own calculations.

639

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c14BCB929-Bulmer 052181290 9 October 6, 2005 14:6

640 Miguel Sz

´

ekely and Andr

´

es Montes

Where Latin America stands out is in the abundance of workers with pri-

mary schooling. The bulk of the working-age population in Latin America

has only achieved some level of primary education. That is not the case

in South Asia, where primary schooling still seems to be a “luxury good”

for most. It is not the case in East Asia, either, but for the opposite reason

that considerable strides have been made in schooling progress. The share

of population that has either no schooling or only primary in that region

is very low.

On the other hand, Latin America falls far behind East Asia, South

Asia, and the world average with respect to the endowment of work-

ers with secondary schooling. Whereas in South Asia, about 33 percent

of the working-age population has achieved secondary schooling, only

20 percent have done so in Latin America. Because the factor is scarcer

in Latin America, it would be expected that local wages for workers with

secondary school would be relatively high; their wages would be relatively

low in South Asia because of greater abundance. The contrast with East

Asia and the world average is even starker.

Latin America is also not well-endowed with workers with higher edu-

cation. Although it has caught up with the rest of Asia, its endowments are

still well below those in East Asia and the world average. Thus, the returns

to these skills in the labor market would be expected to be relatively high

in the region and, consequently, the global demand for them relatively low.

Figure 14.17 plots the world’s effective endowment of skilled labor from

1965 to 1995.

36

The figure demonstrates that the rate of change of the

world endowment declines between 1960 and 1980. This is because of the

entry of China and India into world markets. Because these two countries

have high numbers of unskilled labor, they drive the world average down.

Given this change, Latin America by 1996 seemed to be a region with

human capital endowments very similar to the world endowment, with no

particular advantage in international markets. At the dawn of the twenty-

first century, Latin America neither belongs to the group of countries in

which unskilled labor is highly abundant, nor does it belong to the group

of countries that have made enough schooling progress so as to have an

abundant semiskilled labor work that can compete and be highly rewarded

in world markets.

36

Following Spilimbergo, Londo

˜

no, and Sz

´

ekely, effective endowments are calculated by obtaining the

weighted average of country endowments, where the weight is given by the participation of the

country in world trade (low weights imply that the country’s endowments compete less in world

markets). These authors’ calculations are extended to include the 1992–6 period.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c14BCB929-Bulmer 052181290 9 October 6, 2005 14:6

Poverty and Inequality 641

50

100

150

200

250

1965

687012 579247990

2

Year

35

LAC, 1980

LAC, 1996Skilled labor

World Endowment

79 34

6

8801 3

5

68 1

4

Figure 14.17.Effective world skilled labor endowments.

Sources: Data for 1965–92 are reproduced from Antonio Spilimbergo, Juan Luis Londo

˜

no,

and Miguel Sz

´

ekely, “Income Distribution, Factor Endowments and Trade Openness,”

Journal of Development Economics 59 (1997): 77–101; 1992–7 data are authors’ calculations

using the same methodology and updated data sources.

In the 1980s, the endowment of unskilled labor in Latin America was

higher than the world average (there was relative scarcity of skilled labor),

which suggests that had the region been open to international trade during

the previous decades, it would have been able to exploit its comparative

advantage in goods produced with relative intensity of unskilled labor. Pre-

sumably, this would have reduced the wage gap between the skilled and

unskilled in the region, and could have resulted in inequality and poverty

reductions. As shown in the second section, the evidence indicates that the

opposite happened in reality because the 1980swere years of significant

increases in inequality. Thus, it seems that the region had the right endow-

ments but the wrong policies at that time. Paradoxically, it is the opposite:

the region had the right policies in terms of benefiting from comparative

advantage, but it had the “wrong” human capital endowments.

trade and endowments of physical capital and land

A similar story applies to the case of physical capital, represented here

by the endowment of capital per worker in each country. Figure 14.18