Caballero B. (ed.) Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Technology and Nutrition. Ten-Volume Set

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Commercial importance

Production

0018 The suitability of a region for commercial fruit

production depends on a combination of climate,

adequate water, suitable soils, and access to labor

and markets. Climatically, the rainfall pattern is

most important, as rain can cause major losses from

foliar diseases, fruit splitting, and fruit disease,

leading to direct losses or downgrading. Conse-

quently, a dry summer climate with abundant good

water for irrigation is ideal for fruit production since

the water can be applied precisely as required.

0019 In production areas with high labor costs, much

research is directed towards methods of reducing

the labor component of both production and post-

harvest procedures. Such research includes the use of

new dwarfing rootstocks to reduce the cost of har-

vesting and tree management, planting parameters

to facilitate machine pruning, trellising parameters

to facilitate machine harvesting, tree shakers for

fruit harvest, bulk methods for handling, netting for

hail and pest control, and improved postharvest prac-

tice and facilities.

0020 Varieties and propagation Nearly all major varieties

of the major commercially important temperate fruit

trees are clonally propagated (rather than grown from

seed), either directly by cuttings or by grafting scion

varieties on to rootstocks. The grafting process allows

a productive variety (the scion) of good eating quality

to combine with a different variety (the rootstock)

that better resists endemic root diseases. An add-

itional desirable trait of some (dwarfing) rootstocks

can be a reduction of tree vigour (wasteful leaf and

shoot growth) in the scion, using the incompatibility

between rootstock and scion. New varieties intro-

duced from other regions or countries need to be

assessed for local suitability, since varieties that

produce well in one geographic area often produce

poorly in other areas. At rural horticultural research

centers (‘field stations’) around the world, a substan-

tial proportion of the work on all major commercial

fruits is continually developing new and improved

scions and rootstocks and assessing various root-

stock–scion combinations. New varieties are selected

from either superior bud mutations in existing var-

ieties or, more commonly, concurrent breeding pro-

grams, considering fruit quality, crop yield, and

freedom from disease. While some varieties have a

long history of productive quality, there is a continual

search for new varieties to improve both scion and

rootstock performance. Many new varieties of many

temperate fruits are now being developed purely to

meet changing consumer demands rather than for

production factors such as yield or disease resistance.

0021Some important fruits (e.g., certain apples, plums,

cherries) require cross-pollination for adequate fruit

set, and orchards of these fruits are interplanted with

different varieties.

0022Fertilization Fruit tree production can require fewer

applied fertilizers than broad-acre farming. The

deeper roots have access to nutrients that are more

abundant deeper in the soil. Calcium and potassium

concentrations can also significantly affect fruit qual-

ity. Inadequately fertilized trees result in a poorer fruit

set, smaller fruit size, and increased susceptibility to

pests and disease. Potassium and phosphorus require-

ments are relatively low in fruit crops, but calcium

and trace elements are usually of particular import-

ance to prevent disorders occurring in fruit, although

the trees show no other symptoms.

0023Preharvest pests and disease In most fruit crops,

pests (e.g., insects) and disease (e.g., fungi) are major

problems. Many commercially bred varieties would

be unlikely to survive in nature without human inter-

vention, as they have been selected primarily on the

basis of fruit quality and yield, rather than on pest

and disease resistance. In most production regions,

strict quarantine regulations are enforced to preclude

entry of new pests and diseases.

0024There has been a widespread and general accept-

ance of the need to greatly minimize chemical pesti-

cides by all sectors of the community, including

growers, and recent progress in more environmen-

tally friendly pest control has been quite remarkable.

Integrated pest management (IPM), the established

approach to controlling preharvest pests, is an inte-

gration of chemical, biological physical, and proced-

ural methods. IPM fosters effective populations of the

natural predators of the pest species, allowing a well-

monitored balance between pest and predator

species. If and when the balance is significantly dis-

turbed, a minimum number of carefully applied and

precisely timed applications of chemical sprays are

applied to keep pests or disease within acceptable

limits. The use of insect pheromones that are harmless

to humans is now common in controling many pests.

These are used either as lures on to treated surfaces

containing insecticides or in traps for destruction or

by disrupting mating behavior. There still remains

much to be done in pest and disease control, and

this work constitutes a currently active arena for

researchers from many disciplines.

0025Climacteric and nonclimacteric fruits All fruit are

living organs and as such continue to live and respire

2758 FRUITS OF TEMPERATE CLIMATES/Commercial and Dietary Importance

after harvest. Fruits such as apples, pears, avocados,

tomatoes, and bananas can be harvested slightly

immature but ‘green’ (unripe) without significantly

reducing the final eating quality when they subse-

quently ripen. During this ripening process, complex

polysaccharides, such as starch or pectins, hydrolyze

to sugar resulting in an increase in sweetness and

palatability. All climacteric fruits fall into this

category. The fruit are called ‘climacteric’ fruit be-

cause, concomitantly, their respiration rate develops

a climacteric (peak) as they ripen.

0026 Some other fruits such as citrus, cherries, straw-

berries, grapes, pineapples, and some melons do

not get better to eat after harvest. Although these

fruit may change color, they do not get better to

eat the way that a mature but unripe tomato or

mango will become notably palatable as ripening

proceeds. Concomitantly, these fruit do not have

a climacteric peak of respiration, that is, they are

‘nonclimacteric.’

0027 The postharvest ripening nature of major fruits is

shown in Table 1.

Fruit Maturity

0028 On the tree or bush, an attached fruit undergoes the

natural sequence, whereby it grows (develops),

matures, and commences to ripen. During ripening,

the fruit becomes attractive to eat: softening,

changing colour, losing unpalatable off-flavors such

as tannins, increasing in sweetness, becoming less

acid, and developing attractive flavors.

0029 When a fruit is ‘mature,’ it has reached the most

appropriate state of development and is now ready

for the next stage of its progress, which may be stor-

age, processing, marketing, or ripening for immediate

consumption. ‘Under-mature’ or ‘immature’ means

that the fruit has not yet reached the state of develop-

ment most appropriate for a particular destiny, being

too hard for processing or too unpalatable if con-

sumed. ‘Over mature’ means that the fruit has de-

veloped past the most suitable state of development,

for storage, processing, or marketing. Such fruit may

be too soft, too colored, or too prone to breakdown

during subsequent storage or marketing. A few fruits

(e.g., pears and some bananas) do not reach max-

imum eating quality if left to ripen on the tree, and

in that sense, the fresh fruit could become ‘over-

mature’ for human consumption.

0030 Normally, the commercial fruit is harvested some-

what before the ripening has commenced to avoid

damage during transport, but most climacteric fruit

will improve in eating quality and reach an acceptable

quality, even if picked substantially immature. Ma-

turity is thus independent of ripeness. Fruits can be

immature but unripe, immature and ripe, mature but

unripe, mature and ripe.

0031Nonclimacteric fruits show a dramatic increase in

eating quality during the last several days before nat-

ural ripeness begins, but this process halts at harvest,

and no increase in palatability occurs (or very little).

The exact cause for this different response has not

been fully determined. If nonclimacteric fruits are

harvested even only a few days too early, they most

often lack a full-bodied flavor and palatability. How-

ever, if left too late, such fruits can suffer greatly

increased rots and breakdown during marketing.

Hence, the harvest maturity for nonclimacteric fruits

is crucial and is often determined using a refractom-

eter to measure the ‘soluble solids’ (mainly sugar)

concentration in the juice of sample fruits. This meas-

urement, either alone (pineapples, strawberries) or in

conjunction with titratable acidity measurements

(grapes, citrus), is then used to judge the ‘maturity’

of the fruits.

0032The maturity of the fruits is generally most import-

ant when judging to harvest the first fruit of a district

for the season. For avocados, maturity is commonly

judged using percentage dry matter.

0033The maturity indices mentioned (soluble solids;

percentage dry matter) are destructive in that the

sampled fruit is damaged and usually cannot be

marketed. Considerable effort has been applied to

develop nondestructive indices of fruit maturity, in

particular NIR (near infra-red spectroscopy). This

has been quite successfully used in some thin-skinned

fruits (stonefruit) where a reflected infrared beam is

automatically scanned and analyzed for sugar con-

tent. For other fruits such as citrus or pineapple, the

thick skins currently pose an obstacle to accurate

analysis using NIR. Methods of overcoming this and

other problems for different fruits are currently being

developed.

Harvesting, Handling, and Packaging

0034Harvesting constitutes a major production cost.

Mechanical harvesting is increasingly used in de-

veloped countries, and often where suitable equip-

ment is not currently applicable (e.g., pineapples,

melons), research is in progress. Fruits destined for

processing are often mechanically harvested because

the fruit are processed rapidly before disease can

develop from bruised fruits, and partially damaged

fruits can be trimmed for processing.

0035Commercial fruit production in developed coun-

tries is often large scale and highly capital-intensive,

with sophisticated and specialist equipment used for

all processes, including unloading, washing, sorting,

treating, size-grading, packing, cooling, handling,

FRUITS OF TEMPERATE CLIMATES/Commercial and Dietary Importance 2759

and transporting. Computer tracking and monitoring

are essential components.

Disinfestation and Phytosanitation

0036 Insect pests are generally only of minor importance

on fruit for domestic consumption but are a very

serious issue on produce for export. Most importing

countries have strict regulations (phytosanitary) for

fresh fruit. Many previous chemical dips or fumigants

for pests such as fruit fly have now been proscribed

on human health or environmental grounds. In many

instances, there are no acceptable treatments avail-

able. Nonresidual treatments have been intensively

studied, with increasing success. Heat disinfestation

(formerly termed vapor heat) is the controlled appli-

cation of hot humidified air between 40 and 60

C

and between 80 and 100% RH to fruit in a chamber

for a sufficient length of time to heat the innermost

fruits and fruit core thoroughly to kill the pests

without unacceptably damaging the fruit. The time–

temperature ‘window’ for a treatment is very small

before damage occurs, and many fruits, or fruits from

some growing areas, are unacceptably injured by the

disinfestation treatment. Recent research has revealed

that ‘preconditioning,’ a pretreatment temperature

regimen, is effective in ameliorating damage in other-

wise susceptible fruit. Heat disinfestation is currently

commercially used on papaya, lychees and mangoes,

but current and ongoing research is very active, en-

deavoring to find suitable treatments for many other

fruits. In some instances, it has been found that heat

treatments can greatly reduce postharvest disease and

thus improve the market quality.

Postharvest Aspects of Fresh-market Fruit

0037 Fruits are highly perishable but can be marketed

vast distances from the site of production with the

application of sound postharvest techniques such as

appropriate disease treatment; storage-temperature

management, humidity control, controlled atmos-

pheres, correct packaging and palletizing, ventilation,

and transport carefulness and timely distribution.

Small changes in preharvest conditions, harvest ma-

turity, postharvest handling, storage conditions, new

varieties, farm practices, or season can have dramatic

affects on product quality. With large-scale handling

methods, large-scale losses are a constant hazard to

novice and experienced handler alike.

0038 Storage temperature and humidity Correct tem-

perature maintenance is the most important factor

during marketing, as deterioration from both disease

and ripening increases logarithmically with tempera-

ture. Fruits generally suffer from disorders if stored

for too long or ripened at too low temperatures (the

pear is a notable exception). Such disorders include

off-flavors, breakdown, mealiness, flesh and skin

browning, skin pitting, and increased susceptibility

to disease. For example, peaches and nectarines

suffer textural dryness (become ‘woolly’), whereas

avocados develop off-flavors if stored for too

long below 13

C. If tomatoes have been stored for

too long at 10

C or lower, they develop skin diseases

from organisms that do not normally infect the

fruit (‘saprophytic’ infections). For most fruits, the

optimum ripening temperature is 20–22

C. Con-

versely, some fruits can now be stored at lower

temperatures than previously believed (and have a

longer marketing life) provided that they are removed

from cold storage before ripening commences.

Recommended storage temperatures and maximum

storage times are shown in Table 1.

0039Different cultivars, different production areas and

different seasons can radically affect the tolerance to

cold temperatures. Compared with tropical fruits,

many temperate fruits can be held at much lower

temperatures without any adverse affects, and a few

can have relatively long storage lives. Apples can be

stored for up to 12 months, citrus for up to 16 weeks,

but stone fruit only 2–4 weeks and strawberries only

3–8 days.

Fruit Ripening and Respiration

0040Harvested fruits, being living tissue, respire during

their postharvest life, taking up oxygen, ‘burning’

sugars, and giving out both carbon dioxide and heat

at a rate directly proportional to the ambient

temperature. When fruit is stacked, stored, or trans-

ported, sufficient refrigeration capacity is required to

cope with any climacteric (peak) respiratory heat load

that is autocatalytic. If not controlled, total break-

down can occur. Certain fruits (e.g., strawberries,

peaches), have high rates of respiration and hence

need special attention to cooling, but generally, all

fruits destined for distant marketing need some re-

frigeration. Warm fruit that are not promptly cooled

have a reduced market life, and runaway deterioration

is a risk. In stacked produce, the cardboard cartons act

as insulating containers, preventing cooling. Forcing

air through such stacked trays or boxes (‘forced-air

cooling’) is widely used in warm climates to rapidly

remove field heat after harvest or prior to transport,

reducing the respiration rate and consequently the

rate of the heat production.

0041During ripening, many fruits produce ethylene gas,

a potent plant hormone that initiates and catalyzes

the commencement of ripening. Ethylene production

in fruit follows a similar climacteric production to

2760 FRUITS OF TEMPERATE CLIMATES/Commercial and Dietary Importance

respiration, but some fruit produce much higher

ethylene levels than others. Table 1 shows the pro-

duction rates for the different fruits. Ethylene from

fruit can trigger senescent changes such as yellowing

or withering in vegetables or flowers, or ripening in

adjacent fruits. For this reason, during transport,

fruits that produce substantial amounts of ethylene

are sometimes isolated. Alternatively, ethylene in

store room atmospheres is sometimes destroyed with

ozone from special generators, or absorbed, using

porous alumina beads impregnated with potassium

permanganate and used as small disposable sachets in

fruit cartons.

0042 Effects of fertilizers on fruit quality and superior

taste Whilst soil mineral composition and/or

applied fertilizers have major affects on tree vigour

and fruit yield, fruit quality is much less directly

affected. The perceived ‘sweetness’ or ‘flavor’ of su-

perior fruits depends on a three-way balance between

the concentrations of sugar, acid, and flavor compon-

ents. In an orchard, the concentration of sugar per

fruit, generally an index of the superior taste, can vary

from plant to plant or season to season. Sweetness

usually decreases proportionally with increasing fruit

mass per unit leaf area per plant. In general, for any

particular variety, the flavor components depend on

fruit maturity, the sugar concentration depends on

ambient light intensity and leaf area, and acid concen-

tration depends on ambient temperatures. The flesh

color of some fruits at least (e.g., citrus) depends on

day/night temperatures.

0043 Deficiencies of some elements such as calcium,

boron, and molybdenum affect shape, internal and

external blemishes and storage disorders in some

fruits more than others. A high calcium/potassium

ratio in apples is used as an index of storage quality

as it reduces softening during storage. In citrus

fruits, applying extra potassium increases acidity,

sometimes seen as a desirable factor. Applied nitrogen

encourages leaf growth and photosynthetic efficiency,

which can result in more sugars, thus giving sweeter

fruit. In general, prevailing weather, applied water,

pests, and diseases have a much greater influence on

fruit quality than do mineral nutrition or applied

fertilizer.

Globalization and the Future of Horticultural

Research

0044 Increased economic globalization over recent times

has brought about a major decline of both economic

viability and research support within horticulture

in first-world countries. Third-world countries are

becoming the heirs to the resources as their research

institutions have often been fostered with using

aid from first-world countries. During this same

period, large numbers of horticultural research

workers in first-world research systems have steadily

been not replaced, while third world horticulture and

horticultural research has dramatically expanded.

The problem of the deinstitutionalization of the horti-

cultural knowledge base in first world countries is

now a serious challenge as career researchers are

replaced with casual workers, and the institutional

structure is eroded away. Concurrently, domestic

horticultural production in first-world countries is

being forced to compete with produce from third-

world regions. The whole issue is contentious and

politically challenging, and a situation that has stead-

ily deteriorated for many years without any clear

vision of resolution.

See also: Ascorbic Acid: Properties and Determination;

Physiology; Dietary Fiber: Properties and Sources;

Fruits of Temperate Climates: Factors Affecting Quality;

Fruits of Tropical Climates: Commercial and Dietary

Importance; Fruits of the Sapindaceae; Fruits of the

Sapotaceae; Lesser-known Fruits of Africa; Fruits of

Central and South America; Gums: Properties of

Individual Gums; Pectin: Properties and Determination;

Food Use; Vitamins: Overview; Determination

Further Reading

Anonymous (1982) Fruit and Vegetables Facts and

Pointers. Virginia: United Fresh Fruit and Vegetable

Association.

Anonymous (1989) Fresh Produce Manual. Handling &

Storage Practices for Fresh Produce, 2nd edn. Location:

Australian United Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Association

Ltd.

Block G (1991) Dietary guidelines and the results of food

consumption surveys. American Journal of Clinical

Nutrition 53: 356S–357S.

FAO (1999) Food and Agriculture Yearbook Statistic Series

No. 148. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization.

Hardenburg RE, Watada EE and Wang CY (1986) The

Commercial Storage of Fruits, Vegetables, and Florist

and Nursery Stocks. USDA Handbook No. 96. Wash-

ington, DC: United States Department of Agriculture.

Hughes D (1999) Marketing fruit in Europe. In: Good Fruit

and Vegetables, pp. 34–35. Melbourne: Rural Press.

Kader AA (ed.) (1992) Postharvest Technology of Horticul-

tural Crops, 2nd edn. Location: University of California

Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources.

FRUITS OF TEMPERATE CLIMATES/Commercial and Dietary Importance 2761

Fruits of the Ericacae

J F Hancock and R M Beaudry, Michigan State

University, East Lansing, MI, USA

J J Luby, University of Minnesota, St. Paul, MN, USA

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Global Distribution

0001 The family Ericaceae is perhaps best known around

the world for its showy garden members such as

rhododendrons and heathers. However, some 13

genera contain species with fleshy berries, which are

consumed locally in many parts of the world

(Table 1). The fruits of these species are commonly

eaten fresh or sometimes dried. Many are processed

into preserves, juice, or wine.

0002 Vaccinium is the most important genus in terms of

fruit production. The majority of species inhabit open

mountain slopes in the tropics, with the balance being

distributed in subtropical, temperate, and boreal

regions of the northern hemisphere. Plants of Vacci-

nium vary in form from epiphytes to trailing vines to

trees, with the majority being terrestrial shrubs. Some

form crowns, whereas others produce new aerial

shoots from rhizomes. Flowers may be solitary or in

racemes or clusters.

Commercial Importance

0003 Commercial fruit production is mainly from species

of section Cyanococcus (cluster-fruited blueberries),

including cultivars of V. corymbosum L. (highbush

blueberry) and V. ashei Reade (rabbiteye blueberry)

and native stands of V. angustifolium Ait. and V.

myrtilloides Michx. (lowbush blueberries). Vacci-

nium macrocarpon Ait. (large cranberry), a member

of section Oxycoccus, is also an important domesti-

cated fruit, although most of the cultivars were

selected from the wild. Vaccinium myrtillus L. (bil-

berry, whortleberry), in section Myrtillus, is collected

exclusively from the wild. Vaccinium vitis-idaea L.

(lingonberry, mountain cranberry or cowberry), in

section Vitis-idaea, is also collected predominantly

from the wild, although it has recently been domesti-

cated.

0004 The highbush blueberry is by far the most import-

ant commercial crop, producing over 95 000 t of fruit

annually on over 20 000 ha. Highbush production

occurs in 36 states in the USA, in six Canadian prov-

inces, and in Europe, Australia, and New Zealand.

Highbush plants have recently been established

in South American countries, especially Chile. The

largest acreages are in Michigan, New Jersey, and

North Carolina in the USA, and British Columbia in

Canada. Interest is growing in California. Half-high

types (V. corymbosum V. angustifolium) have

made an impact in Minnesota and regions too cold

to successfully grow pure highbush.

0005The commercial production of rabbiteye blue-

berries is largely confined to southeastern USA,

centered in Georgia, and extending from North Car-

olina to Texas. The estimated area in production in

the USA is over 3000 ha with approximately half of

this in Georgia. The total annual production is over

5500 t. There is also interest in growing rabbiteye

blueberries in warm temperate and subtropical

regions of the world, such as southern African and

South American countries.

0006The commercial production of lowbush blueberries

is largely confined to approximately 50 000 ha in

Maine (USA) and Quebec and the Maritime Prov-

inces of Canada. Maine has only 43% of the hectar-

age, but generates over half of the production. Annual

production now exceeds 55 000 t. Cranberry produc-

tion is over 200 000 t annually from over

15 000 ha, primarily in Wisconsin, Massachusetts,

New Jersey, Washington, Oregon, and Nova Scotia.

A major planting of cranberries was also recently

made in Chile, along with modest plantings in Ire-

land, the UK, and northern Europe. Lingonberries are

commonly harvested in Scandinavia, the former

USSR, Poland and several other European countries,

and in eastern Canada, whereas bilberries are

gathered and consumed primarily throughout north-

ern Europe, Siberia, and northeastern China.

Varieties

0007Highbush blueberry breeding was begun by Dr.

Fredrick Coville of the US Department of Agriculture

in 1908. Over 70 cultivars are now available, al-

though only two, Bluecrop and Jersey, constitute

more than half the hectarage. Bluecrop is the most

dominant cultivar, owing to its high yields and long

storage life, and now encompasses about a third of

the total hectareage. It is the leading cultivar in nearly

all production regions, and its acreage is still increas-

ing. Most of the Jersey acreage is located in Michigan,

and it is no longer being actively planted. Among the

newer releases, Elliott and Duke are the most popular.

Other important cultivars include Croatan, Blueray,

Bluetta, Weymouth, Berkeley, Patriot, Bluejay, and

Rubel.

0008Beginning in the 1970s, the introduction of high-

bush cultivars with a low chilling requirement

for budbreak (so called ‘low-chill’ or ‘southern’

highbush) heralded the extension of ‘highbush type’

blueberry culture into more southern latitudes in the

USA and Australia. Sharpblue is now the most widely

2762 FRUITS OF TEMPERATE CLIMATES/Fruits of the Ericacae

tbl0001 Table 1 Species of the family Ericaceae with edible fruits

Genus and species Geographicrange Uses

a

Vaccinium angustifolium Ait. Eastern N. America D, F, P, J

V. andringtrense Perr. Madagascar D, F, P

V. arbuscula (A. Gray) Mart. Western N. America D, F, P

V. arctostaphylos L. Southern Europe D, F, P

V. a s h e i Reade Southeastern USA D, F, P

V. berberifolium (A. Gray) Skotts Hawaii D, F, P

V. b o r e a l e Hall & Ald. Eastern N. America D, F, P

V. caespitosum Michx. N. America D, F, P

V. confertum Kunth Mexico D, F, P

V. consanguineum Klotzch Mexico, C. America D, F, P

V. corymbosum L. Eastern N. America A, D, J, F, P

V. c y l i n d r a c e u m Sm. Azores D, F, P

V. darrowi Camp Eastern N. America D, F, P

V. d e l i c i o s u m Piper Western N. America D, F, P

V. dentatum J. Sm. Hawaii F, P

V. erythrocarpum Michx. Eastern N. America

V. floribundum H.B.K. Andean S. America D, F, P

V. h i r s u t u m Buckl. Eastern N. America D, F, P

V. l e u c a n t h u m Schlect. Mexico D, F, P

V. l i t t o r e u m Miq. Malaysia D, F, P

V. macrocarpon Ait. Eastern N. America D, J, P

V. m e m b r a n a c e u m Dougl. ex Hook. Western N. America A, D, F, J, P

V. meridionale Sw. Jamaica D, F, P

V. m o r t i n i a Benth. Andean S. America D, F, P

V. myrsinites Lamarck Southeastern USA D, F, P

V. myrtillus L. Europe, Asia, N. America A, D, F, J, P

V. myrtillodes Michx. N. America D, F, P

V. m y r t o i d e s (Blume) Miq. Philippines F, P

V. oldhamii Miq. Eastern Asia D, F, P

V. oxycoccus L. Europe, Asia, N. America D, P

V. ovalifolium Smith Western N. America D, F, P

V. padifolium Sm. Madeira D, F, P

V. pallidum Ait. Eastern N. America D, F, P

V. p r a e s t a n s Pamb. Eastern Asia D, F, P

V. stamineum L. Eastern N. America D, F, P

V. tenellum Ait. Eastern N. America D, F, P

V. u l i g i n o s u m L. Europe, Asia, N. America D, F, P

V. vitis-idaea L. Europe, Asia, N. America D, P

Arbutus unedo L. Mediterranean A, D, F, P

Arctostaphylos arguta Zucc. Mexico M

A. manzanita Parry Southwestern USA A, P

A. pungens H.B.K. Mexico, Southwestern USA D, F, P

A. tomentosa Pursh Western N. America A, D, F, P

A. uva-ursi (L.) Spreng. Europe, Asia, N. America D, F, P

Gaultheria antipoda Forster Tasmania, New Zealand F

G. hispida R.Br. Australia

G. hispidula (L.) Torr. & Gray Eastern N. America F

G. myrsinites Hook. Western N. America P

G. procumbens L. Eastern N. America P

G. shallon Pursh. Western N. America D

Gaylussacia baccata (Wang.) Koch Eastern N. America F, P

G. brachycera (Michx.) Gray Eastern N. America F, P

G. dumosa (And.) T. Eastern N. America F, P

G. frondosa Torr. & Gray Eastern N. America F, P

G. ursina Curtis Eastern N. America F, P

Macleania ecuadoriensis Horold Ecuador F

M. popenoei Blake Ecuador F

Menziesia feriuginea Sm. Western N. America D, F

Chiogenes hispidula (L.) Hitchc. N. America F, P

Disterigma margaricoccum Blake Ecuador F

D. popenoei Blake Ecuador F

a

Uses of fruits: A, fermented for alcoholic beverage; D, dried; F, eaten fresh; J, juice; M, medicinal; P, cooked preserves, jelly, or jam.

From Uphof JCT (1986) Dictionary of Economic Plants. Leure, Germany: Cramer J; Usher G (1974) A Dictionary of Plants used by Man. London: Constable.

FRUITS OF TEMPERATE CLIMATES/Fruits of the Ericacae 2763

planted southern highbush blueberry. Other import-

ant low-chill cultivars are Reveille, O’Neal, Star,

Misty, Gulfcoast, and Floridablue. Of the half-high

types released for northern cold regions, Northblue

and Northland are the most popular.

0009 Over 25 cultivars of rabbiteye blueberries have

been released since their breeding began in the

1930s. Tifblue and Climax form the foundation for

the present industry, and Brightwell Premier and

Powderblue are also being actively planted. In

addition, the very-low-chilling cultivars Beckyblue

and Bonita are gaining in importance in Florida.

0010 Although lowbush breeding programs existed in

Maine, Michigan, West Virginia, Wisconsin, Minne-

sota, and Nova Scotia at various times, the industry is

still based on native selections. Only seven cranberry

cultivars account for about 90% of the crop, and

all these varieties were selected from the wild in

the nineteenth century. Early Black, Stevens, and

Searles represent at least half of the area, with

most of the remainder being Ben Lear, Pilgrim,

Howes, and McFarlin. Most of the new hectareage

is Stevens, Ben Lear, and Pilgrim because of their high

color.

0011 Selection and breeding of lingonberries was

initiated in the late 1960s in Sweden, and the crop is

now being domesticated at several locations across

Europe, Scandinavia, and, most recently, the USA. At

least 12 cultivars have been released: Sussi and Sanna

in Sweden, Koralle, Ammerland, and Red Pearl in

The Netherlands, Erntekrone, Erntedank, and Ernte-

segen in Germany, Masovia in Poland, and Splendor

and Regal in the USA.

Morphology and Anatomy of the Fruits

0012 The fruits of all flesh-fruited ericaceous species are

berries containing many seeds. A waxy cuticle covers

the epidermis of the fruit. In blueberries, the fruit are

held on corymbs or racemes. Pure inflorescence buds

are formed in the late summer and autumn on shoots

of the current season. In cranberries, the fruits are

borne singly at nodes 3 to 5 on upright shoots that

develop from mixed buds on the trailing vines. Fruit

of lingonberries are held in drooping racemes on

terminal inflorescences. Bilberries are borne singly in

the axils of the lowermost leaves of the vegetative

shoot.

0013 The Vaccinium berry contains one to 50 seeds

surrounded by a fleshy and, usually, colorless meso-

carp. In most genotypes, seeds are necessary for

normal fruit development, although varying levels

of parthenocarpy exist. The ultimate size of fruits

is strongly correlated with the number of seeds per

fruit.

0014Blueberry fruit enlarge following pollination,

according to a double sigmoidal growth curve, and

they go through several phases of color development:

(1) immature green, (2) translucent greenish white,

(3) greenish pink, (4) blue–red, and (5) completely

blue. Up to 50% of the increase in berry volume

occurs during the shift from greenish pink to blue.

Flowering occurs in early spring, and the fruits are

ripe in 40–60 days, depending on the variety and

environmental conditions. (See Ripening of Fruit.)

0015Cranberries also go through several stages of color

development, including green, white, and red. How-

ever, the size development of the fruit is more linear

than blueberry. Once berry growth begins, it con-

tinues at a relatively constant rate for 4–6 weeks.

Cranberry fruit matures between 60 and 120 days

after blossom.

0016The anthocyanin pigments that give the fruits their

characteristic colors are in the cells of a surrounding

endocarp layer. A layer of wax often covers the sur-

face of the berry. The light blue color of many blue-

berry cultivars results from the combination of dark

blue pigments overlaid by the translucent wax. Tem-

perature plays an important role in the development

of color, as picked fruit will develop a normal color at

16–27

C whether they are shaded or not, whereas

lower temperatures stop normal development. The

blueberry and cranberry are mildly climacteric, with

only modest elevations in respiration and ethylene

production associated with fruit ripening. (See Color-

ants (Colourants): Properties and Determination of

Natural Pigments.)

Chemical and Nutritional Composition

0017An average blueberry fruit is composed of approxi-

mately 83% water, 0.7% protein, 0.5% fat, 1.5%

fiber, and 15.3% carbohydrate (Table 2). Cranberries

contain 88% moisture, 0.2% protein, 0.4% fat,

1.6% fiber, and 7.8% carbohydrate. Blueberries are

3.5% cellulose and 0.7% soluble pectin, and cran-

berries contain 1.2% pectin. The total sugars of blue-

berries amount to more than 10% of the fresh weight,

bilberries average 14%, and cranberries contain 4%.

The predominant reducing sugars in blueberries are

glucose and fructose, which represent 2.4%. The

edible portion of the cranberry is composed of

2.66% glucose, 0.74% fructose, and 0.14% sucrose.

Its pulp contains measurable amounts of lignin,

glucose, arabinose and xylose. Refer to individual

nutrients.

0018The overall acid content of Vaccinium fruit is rela-

tively high. Ripe cranberries range from 2 to 3%,

whereas blueberries fall in the range of 1–2%. The

primary organic acid in blueberries is citric acid

2764 FRUITS OF TEMPERATE CLIMATES/Fruits of the Ericacae

(1.2%). They also contain significant amounts of

ellagic acid, a compound thought to reduce the risk

of cancer. The cranberry contains high levels of

several organic acids, including quinic (1.3%), citric

(1.1%), malic (0.9%), and benzoic (0.6%); lingon-

berries also have very high levels of benzoic acid.

Ingestion of cranberries or lingonberries leads to in-

creased acidity of the urine through conversion of its

high quinic and benzoic acid contents to hippuric acid

by the body. The high acidity and possible antibacter-

ial effects of hippuric acid may relieve urinary tract

infections and reduce some types of kidney stones.

(See Acids: Natural Acids and Acidulants.)

0019 Compared with other fruits and vegetables, blue-

berries and cranberries have intermediate to low

levels of vitamins, amino acids and minerals

(Table 2). Blueberries contain 22.1 mg of vitamin C

per 100 g of fresh weight, and cranberries contain

7.5–10.5 mg. Bilberries contain 5 mg of N per 100 g

of alcohol-soluble nitrogen, whereas blueberries

contain 15–60 mg of N per 100 g. Blueberries are

unusual in that arginine is their most prominent

amino acid. Glutamic acid and valine predominate

in bilberries, and lingonberries contain high levels of

serine and aminobutyric acid. Lingonberries also pos-

sess appreciable levels of the unusual amino acids

1-aminocyclopane-1-carboxylic acid and 5-hydroxy-

pipecolic acid.

0020In general, blueberries and bilberries are two of the

richest sources of antioxidant phytonutrients among

the fresh fruits, with total antioxidant capacity

ranging from 13.9 to 45.9 mmol of Trolox equivalents

per gram of fresh berry. Berries from the various

Vaccinium species contain relatively high levels of

polyphenolic compounds, with chlorogenic acid

predominating. Total anthocyanins in blueberry

fruit range from 85 to 270 mg per 100 g, and species

in the subgenus Cyanococcus carry the same predom-

inant anthocyanins, aglycones and aglycone sugars,

although the relative proportions vary. The predom-

inant anthocyanins are delphinidin monogalactoside,

cyanidin monogalactoside, petunidin monogalacto-

side, malvidin monogalactoside, and malvidin

monoarabinoside.

0021Among the other Vaccinium spp., cranberries have

total anthocyanins varying from 25 to 100 mg

per 100 g fruit, with the most important anthocyanins

being cyanidin-3-monogalactoside, peonidin-3-

monogalactoside, cyanidin-3-monoarabinoxide, and

peonidin-3-monoarabinoside. Cowberries contain

high quantities of cyanidin-3-galactosides. Bilberries

contain high quantities of hydroxycinnamic acid and

possess very high levels of quercitin-3-glucoside,

rhamnoside, and arabinoside. The various Ericaceae

species also contain appreciable amounts of several

carotenoids.

0022The major volatiles contributing to the characteris-

tic aroma of blueberry fruit are trans-2-hexanol,

trans-2-hexanal, and linalool. The predominant

volatiles in the bilberry are trans-2-hexanal, ethyl-

3-methyl butyrate, and ethyl-2-methyl butyrate. In

the cranberry, 2-methyl butyrate is rare, but a-terpi-

neol predominates. Benzaldehyde also contributes to

the aroma of the cranberry. (See Sensory Evaluation:

Aroma.)

Handling and Storage

0023Most fresh-marketed fruits of Vaccinium are har-

vested by hand, although lowbush blueberries are

commonly removed from the bush with hand-held

rakes. Highbush and rabbiteye berries are mechanic-

ally harvested for the processed market with over-

the-row machines that shake or beat the fruit on to

catching pans or conveyors. Fruits are mechanically

harvested as a clean-up operation after several hand-

pickings, or when 60–70% of the fruit on a bush are

tbl0002 Table 2 Composition of 100 g of fresh Vaccinium species

Constituent Blueberry Cranberry

Energy value

Food energy (kJ) 260.4 109.2

Chemical composition (%)

Moisture 83.20 88.00

Reducing sugars 12.75 4.20

Nonreducing sugars 1.46 0.11

Acids (as citric) 1.15 2.40

Pectin 0.66 1.20

Fat (ether extract) 2.60 0.40

Protein 0.70 0.20

Ash 0.30 0.25

Fibre 1.50 1.60

Mineral content (mg)

Potassium 81.0 53.0

Sodium 1.0 2.0

Calcium 15.0 13.0

Phosphorus 13.0 8.0

Magnesium 5.3 5.5

Iron 1.0 0.4

Vitamin content

Vitamin A (IU) 100.0 40

Vitamin C (mg) 22.5 7.5–10.5

Thiamin (B

1

) 0.03 mg 13.5 mg

Riboflavin (B

2

) 0.06 mg 3.0 mg

Nicotinic acid (mg) na 33.0

Pantothenic acid (mg) na 25.0

Pyridoxine (B

6

)(mg) na 10.0

Biotin na Trace

Niacin (mg) 0.50 na

na, not applicable.

From Eck P (1988) Blueberry Science. New Brunswick: Rutgers University

Press; Eck P (1990) The American Cranberry. New Brunswick: Rutgers

University Press.

FRUITS OF TEMPERATE CLIMATES/Fruits of the Ericacae 2765

blue. A limited amount of fruit is mechanically

harvested for the fresh market, but only with careful

sorting to remove defective fruit.

0024 Cranberries are mechanically harvested either dry

or wet. Dry harvested fruit are generally stripped

from the vines with a picking machine that combs

or scoops fruit off the plant. To wet harvest fruit, the

bogs are flooded to lift the vines, and the floating fruit

are raked or beaten off the surface of the water. Wet

harvesting recovers a higher percentage of the fruit,

but water-raked berries deteriorate more rapidly.

0025 A typical grading line for fresh-marketed blue-

berries consists of a ‘blower’ to remove leaf material

and small green berries, a ‘tilt belt’ to separate soft

from firm fruit, and a sorting line, where four to eight

people visually scan the fruit for defects. Grading

lines for processing berries are usually composed, in

order, of a blower, tilt belt, a water tank, where ripe

berries sink, a fruit destemmer, and a sorting line.

Processed berries are generally frozen either in bulk

or individually quick-frozen. The color of blueberries

is well preserved by freezing, although they form

exudates and redden upon thawing.

0026 Dry-harvested cranberry fruit are generally sorted

by bouncing them over a barrier board. Sound berries

bounce and travel forward on a conveyor belt, and

soft berries are collected below. Small and large

berries are then separated over a wire screen and

carried along moving belts for further sorting.

Water-harvested berries are first dumped on a long,

inclined mesh belt that passes through a dryer to

prepare them for sorting. Flotation tanks are also

used in some instances to sort both wet- and dry-

harvested fruit.

0027 Suggested quality standards for sorted blueberry

fruit are as follows: (1) pH at 2.25–4.25; (2) citric

acid at 0.3–1.3%; (3) soluble solids, greater than

10%; (4) ratio of soluble solids to acid, 10–33%;

(5) firmness, greater than 7 g of force for 0.01 cm of

deformation on the Instron testing machine; (6) diam-

eter, greater than 10 mm; (7) color, blue with less than

0.5% of the surface having a pink coloration. Cran-

berry quality is largely determined by its color, par-

ticularly in juice products. Other important quality

traits are sweeter, darker, uniform-colored fruit for

fresh marketing, increased aromas, firmness, uniform

size and shape, organic acids, and glossiness.

Methods have been devised for sorting Vaccinium

fruit by firmness and optical density, and these are

growing in popularity.

0028 Cranberry fruit can be successfully stored for sev-

eral months without any significant losses in quality.

Fruit were once stored for the fresh market in large

ventilated rooms at ambient temperatures, but

now refrigerated storage is recommended at 2–4

C.

Processed berries are generally frozen. Most cran-

berries are stored in bulk, but some berries are pre-

packaged in perforated 0.45-kg cellophane bags or

unsealed cardboard boxes. Storage life can be

extended up to 12 weeks if berries are kept cool in

bulk and packaged just before harvest. Controlled-

atmosphere storage does not appear to have signifi-

cant benefits, except that treatment with ethylene gas

after harvest may increase the anthocyanin content of

the fruit. (See Controlled-atmosphere Storage: Appli-

cations for Bulk Storage of Foodstuffs; Storage

Stability: Mechanisms of Degradation; Parameters

Affecting Storage Stability.)

0029Blueberry fruit are generally packaged in plastic

pint or quart ‘clam shell’ containers, or open contain-

ers that are covered loosely with cellophane or shrink-

wrapped. Shelf-life can be greatly extended by

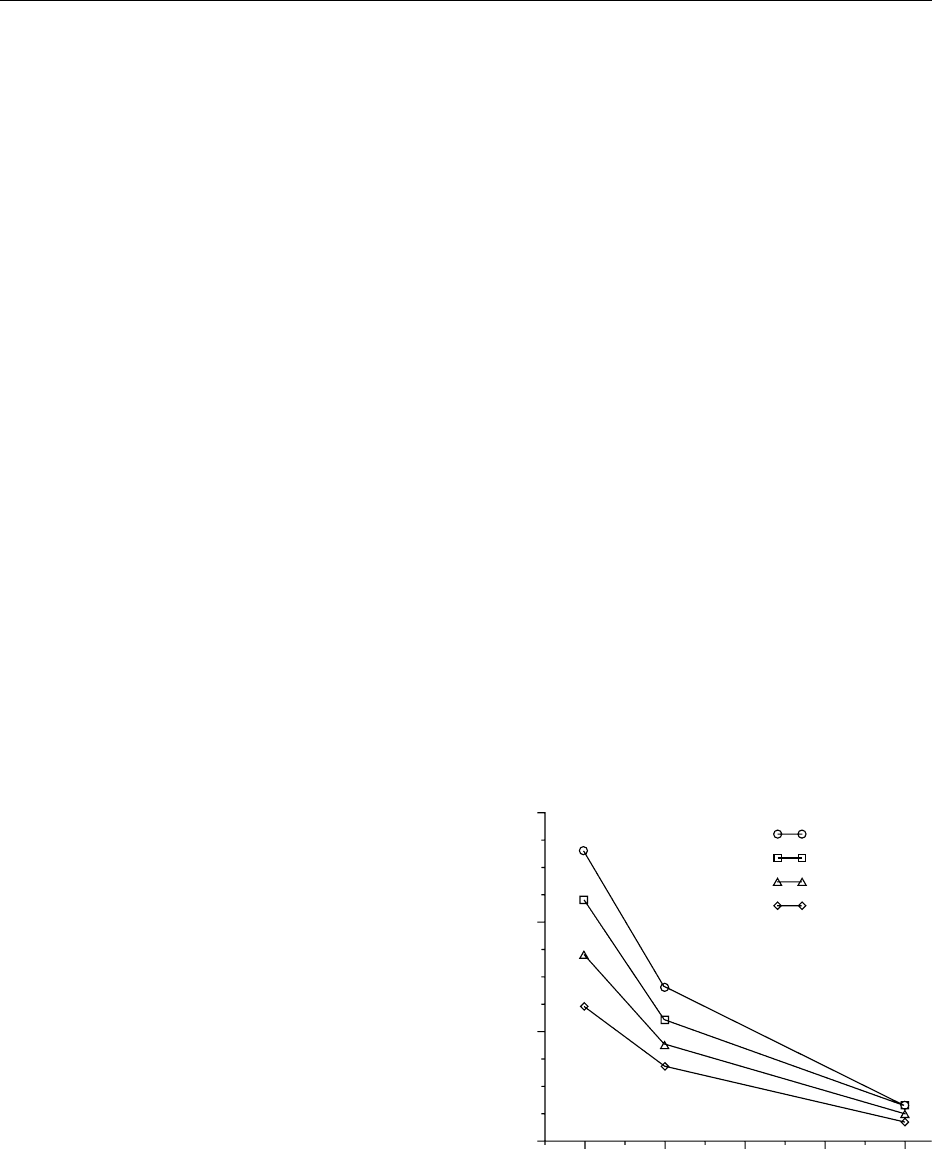

lowering fruit temperatures to 0

C(Figure 1).

Decreasing the storage temperature slows respiration

and other metabolic processes, but even more import-

antly, it greatly reduces the activity of decay organ-

isms (Figure 2). In addition, spore germination of

Alternaria and Botrytis occurs only very slowly at

0

C, whereas germination of Glomerella spores

is stopped altogether. During long-term storage

(3 weeks or more) at 0

C, senescent breakdown

can occur in the berry flesh, leading to the formation

of watersoaked areas and the bleeding of blue skin

pigments into the normally colorless mesocarp.

However, few precautions other than modest chilling

0

0

40

80

120

5 101520

Temperature (⬚C)

Shelf life (days)

Low O

2

Optimal O

2

High O

2

Air

fig0001Figure 1 Effect of storage temperature and atmosphere com-

position on the visual shelf-life (days in marketable condition) of

Bluecrop blueberry fruit sealed in low-density polyethylene pack-

ages. For the various oxygen (O

2

) treatments, the approximate O

2

and carbon dioxide (CO

2

) concentrations were, respectively, as

follows: low O

2

, 0.8% and 12%; optimal O

2

, 2% and 7%; high O

2

,

7% and 3%; air, 21% and 0%.

2766 FRUITS OF TEMPERATE CLIMATES/Fruits of the Ericacae

are generally taken to attain a storage life of 7–10

days. Once the fruit have been cooled below approxi-

mately 10

C, they must be kept chilled to avoid

condensation (‘sweat’) upon returning the fruit to

warm conditions.

0030 Modified atmospheres (elevated CO

2

and low O

2

conditions) can enhance the visual shelf life of blue-

berry fruit (Figure 1), although temperature manage-

ment plays the most important role in maintaining

fruit quality. Lowering O

2

to 2% does not have a

significant benefit by itself, but combinations of low

O

2

and high CO

2

can improve storability. CO

2

levels

of 8–10% or greater can significantly reduce decay

development of blueberry fruit, but may not slow the

decline in internal condition that normally occurs

during storage. Packaging systems presently under

development rely on the fruit, the packaging film,

and temperature control to generate and maintain

optimal O

2

and CO

2

levels. Packages must be

designed to avoid excessively low O

2

levels, or fer-

mentation and off-flavors will result (Figure 3; note

that O

2

partial pressures are in kPa, which can be

read as %). Packaging systems that boost package

CO

2

levels and/or provide some level of humidity

control have been developed for other products and

may have considerable potential for packaged blue-

berry fruit. Chlorine and fungicide dips can also

reduce postharvest decay. (See Chilled Storage: Use

of Modified-atmosphere Packaging; Chill Foods:

Effect of Modified-atmosphere Packaging on Food

Quality; Fungicides.)

Industrial Uses

0031Blueberries and bilberries are eaten both as dessert

fruits and in processed forms. About 46% of the

rabbiteye crop and 50% of the highbush crop are

marketed fresh, and the remainder are processed.

Nearly all commercially harvested lowbush blue-

berries, cranberries, and lingonberries are processed.

0032The first widespread use of cranberries was to

make sauce as a speciality item served at Christmas

and the American holiday, Thanksgiving. During the

1960s, juice products made their appearance in the

USA and now dominate the market. Cranberry ‘cock-

tail’ is drunk alone or mixed with other juice prod-

ucts. Cranberries are also made into a syrup, a dried

raisin-like product, and a natural red food coloring,

which has been used successfully to enhance the color

of cherry pie filling.

0033Blueberries are used primarily in pie fillings,

yogurts, icecream, and prepared muffin and pancake

mixes. Blueberries are sometimes added to dried

products after dehydration using an explosion-

puffing process. Syrups, jams, and preserves are also

produced, but in limited quantities. The juice of blue-

berries is rarely consumed directly as it has a very

strong flavor and dark color.

0034Lingonberries are quite tart, but quite edible when

cooked and are commonly used for juice, pie fillings,

and jam. Bilberries are used fresh or in juice, pre-

serves, or wine. Fruit extracts are also used in

pharmaceutical preparations for the treatment of

microcirculatory diseases.

0

0.0

0.4

0.8

1.2

1.6

51015

Temperature (⬚C)

20 25 30

Oxygen uptake (mmol O

2

per kg per h)

0

10

5

15

25

20

30

Lesion diameter (mm)

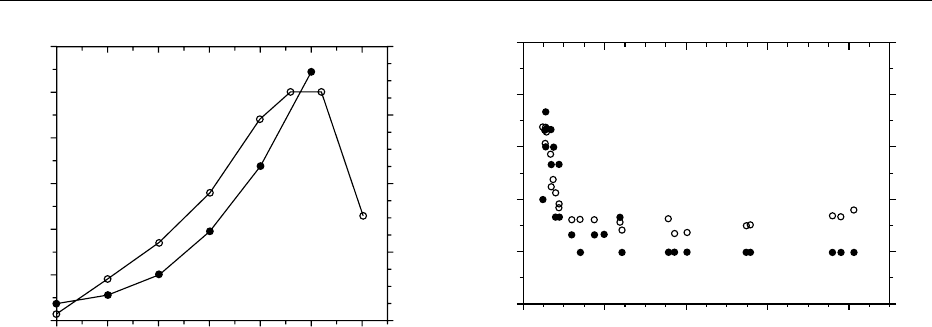

fig0002 Figure 2 Effect of temperature on (s——s) the development

of decay lesions (generalized curve redrawn from Kader AA,

Kasmire RF, Mitchell FG, et al. (1985) Postharvest Technology of

Horticultural Crops. Extension Bulletin 311. University of California

at Davis.) and (

.

——

.

) respiratory metabolism of Bluecrop fruit at

ambient oxygen levels. Adapted from Beaudry RM, Cameron AC,

Shirazi A and Dostal DL (1992) Modified atmosphere packaging of

blueberry fruit: effect of temperature on package oxygen and

carbon dioxide. Journal of the American Society of Horticultural Sci-

ence 117: 436–441, with permission.

0

0

1

2

3

4

5

0

1

2

3

4

5

4 8 12 16

Steady-state O

2

(kPa)

Off-flavour ratin

g

Respiratory quotient

fig0003Figure 3 Effect of oxygen (O

2

) concentration on (s) the respira-

tory quotient (RQ) and (

.

) off-flavor development of Bluecrop

blueberry fruit at 20

C. The increase in the RQ as O

2

levels

decline below 2 kPa is indicative of fermentation.

FRUITS OF TEMPERATE CLIMATES/Fruits of the Ericacae 2767