Campbell P. Power and Politics in Old Regime France, 1720-1745

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

POWER AND POLITICS IN OLD REGIME FRANCE

198

In 1640, Cornelius Jansen’s three-volume Latin Augustinus set out the

Augustinian position in detail, but it was not widely read. It was Antoine Arnauld’s

(1612–94) On Frequent Communion, published in 1643, that really began the quarrel.

Arnauld attacked the Jesuit doctrine that the less grace one had the more frequently

one should take Holy Communion and receive absolution, and the notion that fear

of damnation was an acceptable motive for repentance. He inveighed in French, not

Latin, against the lax morality of his age, against the notion that communion could

be taken lightly, and preached ‘what conforms to antiquity, the traditions of the

saints and the old customs of the Church’. The dispute between Jesuits and

Jansenists was exacerbated by the Jesuit attacks on the newly reformed monastery

of Port-Royal des champs, which had become closely connected with the Arnauld

family. Polemics on both sides and papal condemnation in 1653 of five heretical

propositions supposedly to be found in the Augustinus led to heated debate that was

embittered by Pascal’s scathing but effective attack on the Jesuits in the Provincial

Letters (1656–7).

Jansenism at its most elementary was a set of Catholic beliefs focusing on austere

or pessimist answers to the issues of original sin, grace, predestination, penitence

and communion, and the absolute necessity of love. On the question of grace, it was

argued that God had not accorded sufficient grace to all men, enabling them, by the

virtuous exercise of their free will, to win salvation (the Jesuit position), but instead

made use of his supreme power, his efficacious grace, to grant salvation to a few—this

was therefore a position close to predestination. For the Augustinian followers of

Jansen and Arnauld, man was sinful and corrupt, capable of salvation only with the

help of God’s love and the heroic practice of great virtue and austerity, while the

sacraments should be the culmination of interior conversion. The model of the

primitive church was a powerful one for them, and it was felt both that the modern

world made too many immoral compromises and that the church had strayed too

far from the teachings of St Augustin.

If these may be said to be the essential tenets, subsequent involvement with the

work of directing consciences and the experience of condemnation and conflict

under Louis XIV led to the emergence of diverse tendencies within Jansenism.

These ranged from a pessimistic and uncompromising refusal of the world (as with

Pascal and Port-Royal) to a more optimistic recognition of the existence of natural

rights that accepted the possibility of good institutions as a framework for a

Christian life (as with Nicole). By the end of the century the dominant tendency

was that of Pasquier Quesnel (1634–1719) and Jacques-Joseph Duguet (1649–

1733). They were colleagues for a decade at the Oratorian seminary of Saint-

Magloire, and towards the end of the century both went into exile in Brussels. The

former worked with Arnauld in the Low Countries and became his heir at the head

of the movement. His Moral Reflections on the New Testament had begun life as a defence

of Augustinianism in 1671 and was frequently republished with additions after

1686, being widely accepted at first as an excellent guide to the New Testament.

The latter was one of the most brilliant and erudite theologians of his age, whose

biblical exegesis was to become fundamental to the new Jansenism after 1700.

THE PARTI FANSENISTE IN THE 1720s AND 1730s

199

Although historians have not usually regarded them as strictly in the purest

tradition of Port-Royal, these men and their disciples nevertheless regarded

themselves as the direct spiritual heirs to Port-Royal after its destruction in 1711.

The destruction itself and the comprehensive condemnation of the Jansenist

doctrine in 1713 were taken to be signs of apostasy by the church. This only

heightened the Jansenists’ eschatological zeal and stimulated a reinterpretation of

the Scriptures even then being presented in lectures at Saint-Magloire.

Paradoxically, papal condemnation was a unifying force and a catalyst for

theologico-political action. The Bull Unigenitus had not only provided a focal point

for opposition to the royal anti-Jansenist policy but also drawn together disparate

strands of that opposition. Its terms offended several tendencies in France: the

Port-Royalists were incensed at the attempt to condemn aspects of their doctrine;

some Richerist members of the lower clergy were also offended by the implicit

support given to episcopal authority over them;

11

and many Gallicans in the legal

profession felt it incumbent upon them to protest against the reception of a papal

Bull in France without the full consent of the French church. Many were angered

by Unigenitus, arguing that it condemned perfectly orthodox Catholic doctrine,

and an appeal to a future general council of the church was organised, on the

grounds that such a council was of higher authority than the Pope’s. The parti of

those who identified with this appeal (known as the appellants) therefore included

those adhering to the various shades of Jansenism, be they bishops or curés, and

some lay members of the church, and included Gallicans. The latter soon fell

away as the dispute became increasingly vehement, until the appellants consisted

principally of Jansenists.

12

It was, of course, the specific doctrine of Pasquier Quesnel that had been

condemned by Unigenitus. By the early 1700s he had rapidly become the most

influential theologian in succession to Arnauld and Nicole, whose friend and

collaborator he had been before their deaths in the 1690s. From about 1700, his

doctrinal emphases were very influential, especially in Oratorian seminaries in the

form of the Father Juénin’s Institutiones theologicae, and often had free sway as they

were not condemned as unorthodox until 1708 and 1712. However, later and

augmented editions of Quesnel’s Moral Reflections had been increasingly criticised in

some quarters, as numerous propositions of dubious orthodoxy were added in.

Quesnel always strenuously denied that he was a leader, and in 1711 wrote to

Fénelon: ‘I have no school, and no disciples. I am leader of no parti; I have none, I

am in horror of all faction [parti]; my law is the gospel; the bishops are my fathers;

and the Pope is the first among them’.

13

Such an attitude was typical of Jansenism:

if it was a heresy it was one that insisted that it did not exist and that it was entirely

within the church.

Most previous historians have regarded the struggles of the early eighteenth

century as the period of ‘Quesnelism’; Préclin, author of a ‘standard work’,

regarded the growing conflict as a consequence of a strengthening of Richerism

among the curés.

14

In the light of the recent work by Neveu, on the abbé Jean

Baptiste Le Sesne de Ménilles d’Etemare (1682–1770), and by Catherine Maire

POWER AND POLITICS IN OLD REGIME FRANCE

200

more comprehensively, we should modify these views very considerably.

15

Maire’s

argument is that younger disciples of Quesnel and Duguet, that is to say Jacques-

Vincent Bidal d’Asfeld, d’Etemare, Vivien de La Borde, Fouillou and Laurent-

Etienne Boursier, to name but the most prominent, developed a very influential

form of biblical exegesis that was to be central in motivating many Jansenists in

their future struggles, be they religious or ‘politico-religious’. It was this group that

was behind the organisation of the appeals and the coherent organised resistance to

oppression from the 1720s.

16

It is now clear that Préclin accorded too central a

position to Richerism, taking a single element for the essence; it may be going too

far to suggest, as Maire does, that their new ecclesiology (soon to be called

Figurism) was the core of a new Jansenism, but it was certainly important. To the

present writer, the ‘Figurist’ doctrine seems to have co-existed with previous

currents rather than to have entirely replaced them, especially as so many appellants

were old enough to have received their theological training well before the new

ideas were widely taught.

17

Nevertheless, it is undoubtedly the case that of the

several strands of early eighteenth-century Jansenism, Figurism was the most potent

and the most proactive. It appealed above all to the younger generation.

Its importance lay in its ability to infuse the beleaguered movement with a new

sense of righteousness and urgency, justified by reference to Holy Scripture. This

now forgotten and obscure ecclesiology attempted to interpret the true significance

of the ambiguous and enigmatic prophecies in the Bible. Theologically, it had

antecedents in Christian interpretation of the Scriptures since Saint Paul, for

example, by Joachim of Fiore; it was mentioned by Jansen, and Pascal’s Pensées have

a chapter on ‘Figures’; it is also true that the obdurate theological positions of the

abbé Le Roy and his circle in the 1660s and 1670s offer perhaps an antecedent on a

number of levels.

18

Even so, its full development owed most to the abbé Duguet and

his circle in the first two decades of the eighteenth century. Duguet, the son of an

avocat du roi, was born in 1649 and educated at the Oratorian seminary of Saint

Magloire, where he taught from the 1670s to 1684 and with which he remained

closely associated. He was particularly concerned with the questions of how true

faith perpetuated itself and with the problem of the relationship between the Old

and the New Testaments. His major contribution was to put forward an almost

cyclical theory of church history in which first the Jews and then the gentiles

abandon the true faith, which must therefore once again be carried forward by

another chosen people. The links to be found between the Old and the New

Testaments were consequently of great significance. Beneath the letter of the Bible

lay multiple other readings, and the whole future history of the church was

recounted in its biblical history, which prefigured or symbolised in allegorical form

subsequent and future events. By having the key to the system of metaphors and

analogies, and to the correspondences between them (the figures) it was possible to

make sense of the enigmatic prophecies and discover new significance in the

accounts of events in the Scriptures, particularly in the books of the prophets in the

Old Testament and in the Apocalypse or Revelation.

19

Duguet also put forward the suggestion, which Bossuet himself agreed with, that

THE PARTI FANSENISTE IN THE 1720s AND 1730s

201

after the coming of the prophet Elijah and the conversion of the Jews, both preludes

to the regeneration of the church and Second Coming of Christ, the Apocalypse

would not come immediately but only after an indeterminate but lengthy period, as

God might will. The abbé d’Etemare, who succeeded Duguet as lecturer in 1710 (at

the time of the destruction of the convent of Port-Royal) and whose spiritual

director was Duguet, took these ideas further after a flash of illumination. The story

of Joseph made him see ‘a perfect image resembling all that had happened at Port-

Royal’.

20

The correspondences existed not only between the Scriptures alone but

between the Scriptures and the whole future history of the church. Figurism viewed

the Bible as containing a history of the church that was to be paralleled and repeated

throughout its history: a view that was in tune with cyclical theories of history.

All the personages of the Old Testament, their actions, the events of Jewish

history were symbolic of different persons, of the actions and events of the

new alliance, which is to say of the whole Church since its foundation to the

end of time. Thus Jonah was a prefiguration of Saint Paul. In the same way,

the ancient prophecies did not simply foretell future events, concerning the

Jewish people or Our Lord Jesus Christ, but the whole history of the

Christian Church at its different periods…Above all it tended to apply this to

the present and future situation of the Church.

21

There was now no end to the multiple meanings that could be extracted from the

texts. For example, the conversion of the Jews, while being itself a prophesied future

event, might also refer to the conversion of the present gentiles who formed the

body of the church, and this would be brought about by the ‘depositories of the

Truth’ with the help of the converted Jews. As Maire argues, the idea of an elect

group that was a Dépôt de la Vérité (depository of truth) was to become an essential

element in the evolution of the Jansenist struggle, and would parallel parlementary

political theory which included the notion of a dépôt de la loi. It was claimed that the

history of the church showed that while there was always error, there was invariably

also a body of the faithful who carried forward the true faith. Naturally, the new

Jansenists saw themselves as the embattled defenders of Truth, the elect, and used

their Figurist exegesis to interpret and predict their own times of struggle.

All this required a considerable effort of study and communication. The

abbé d’Etemare was Duguet’s principal collaborator in the elaboration of the

Figurist exegesis, but its first major text was La Borde’s Testament of Truth in the

Church, published in 1714 and republished in 1718.

22

However, d’Etemare was

the real master of Figurism and was closely involved with the resistance to

Unigenitus. Together with Jacques Bidal d’Asfeld and others he worked on a

systematic application of the Figurist method to the Jansenist position. In

lectures from 1712 to 1714 at Saint-Magloire, more widely from 1710 to 1721 in

the parish of Saint-Roch, and during the 1720s and 1730s in publications,

d’Etemare and d’Asfeld explained the enigmas of the Scriptures to the laity,

preaching that the arrival of Elijah was imminent, the conversion of the Jews

POWER AND POLITICS IN OLD REGIME FRANCE

202

not far off and the Second Coming to be expected soon thereafter, all of which

would lead to the destruction of the new Babylon (Rome) and regeneration of

the church. The hard core of the appellant resistance was closely associated

with Figurism, no doubt because it gave disciples urgent reasons for active

intervention by amis de la vérité. The attack on the Bull Unigenitus was to be

carried out with millenarian fervour.

The total number of Jansenists is hard to estimate but the signatures of the

appeals to a future council of the French church indicate about 7,000 clergymen in

1718, or about only 5 per cent of the clergy, falling to 3 per cent by 1728. The appeal

was accepted by about twenty bishops (about 15 per cent of the 130), some of

whom gave protection to Figurists and Quesnellists in their dioceses, among which

were Auxerre, Boulogne, Pamiers, Verdun, Senez, Montpellier, Mirepoix, Troyes,

Blois and, of course, Paris where Noailles was archbishop. All except Jean Soanen

the bishop of Senez were from influential noble families, and if they were open to

ministerial pressure, as in the case of archbishop Noailles, they could not be

attacked too severely. Individual priests formed the mass of appellants and often

converted their parishioners, but they could be exposed to severe pressure by the

episcopate aided by the royal council with lettres de cachet. However, these members

of the lower clergy were by no means the poorly educated parish priests one has in

mind for the early seventeenth century. They were well educated, having attended

the leading theological seminaries, especially those of the Oratory, and were almost

all of bourgeois or aristocratic extraction, in most cases being younger sons of

wealthy families. They would have been familiar with the history of Conciliarism,

but also with Descartes, Pascal, Malebranche and all the debates on biblical exegesis

and morality. A certain number of Oratorian or Benedictine seminaries and

monasteries also provided shelter, and here again the state had limited powers of

coercion.

Paris was the stronghold, with Troyes a close second. In Paris the lower clergy in

some of the parishes was entirely won over to Jansenism, and was supported by the

lay churchwardens.

23

In Sainte-Marine the curé Isoard preached the doctrine every

Sunday; the parish of Saint-Germain-le-vieux was Jansenist right through to 1743;

the cure of Saint-Séverin was won over in 1730; Saint-Etienne-du-Mont, Saint-

Médard, Saint-Nicolas-des-Champs and Saint-Barthélemy were all entirely in the

hands of the parti janséniste. Quesnellist catechisms were used to instruct

parishioners, Jansenist books of ritual were practised in church services, while

sermons, biblical exegesis, confession and pastoral instruction all served to spread

the Figurist message. Convents, charity schools and colleges provided havens for

Figurist confessors and forums for the round of sermons by others of the parti. Both

the convent of the Filles de Saint-Agathe and the college of Sainte-Barbe taught its

pupils the Figurist doctrines, as did the seminary of Saint-Hilaire, presided over by

Jérome Besoigne, and most important of all was Saint-Josse, the community of

priests where there were daily lectures. A police report in the 1730s protested that

‘this community is the most pernicious there has ever been, since it is a collection of

the most notorious Jansenists, convulsionaries, augustinians, eliseans, mélangistes,

THE PARTI FANSENISTE IN THE 1720s AND 1730s

203

of authors and distributors of the Nouvelles ecclésiastiques and of all sorts of works

against the Constitution’.

24

Jansenism was a highly literate creed, and the new Figurism was nourished by

theological controversy in the form of hundreds, indeed more than a thousand,

books and pamphlets published from 1713 to the late 1730s. Even in 1739 after

years of governmental pressure, some twenty printers and booksellers in the

university quarter were still believers, making it hard to stem the tide. Jansenist

publications were peddled to the faithful after mass or delivered to the communities,

and could be easily bought. If some texts were concerned with refuting the Jesuits,

others were aimed more directly at the educated parishioners such as

churchwardens who had considerable powers in a parish. Jansenism encouraged

the reading of the Scriptures in French by the laity—and there was a wave of

translations of the Bible published from the 1690s to the 1730s—while that famous

refutation of Unigenitus, the Hexaples of 1713–21, named after its format in six

columns, not only made the Bull Unigenitus available in French but also confronted

it on the same page with the relevant passages from Scripture with commentary.

Catechisms, confession and the elementary instruction in the parish schools

25

could

not have given the poorer laity a proper understanding of the theological

complexities, but the subsequent involvement of many poor women and men in the

miracles, in the convulsionary movement and the distribution of literature does

prove that strong tendencies at least had been generated.

How widespread was the message by 1730? Although the network of contacts

described above was to be a structure within which opposition could be organised,

it would nevertheless be wrong to exaggerate the movement’s overall strength.

Indeed, part of the fascination in the group lies in their entirely disproportionate

effect compared to their small numbers. The appellants certainly felt weak and

persecuted, as indeed they were. The policy of government and episcopal pressure

against the appellants had been increasingly successful during the 1720s. Some have

argued that it was this persecution which led the Jansenist party to resort

deliberately to the belief in miracles as a proof of the divine justice of their cause.

26

A

contrary view (held most recently by Kreiser) has taken a statement of the lawyer

Barbier rather too literally—‘tout Paris était janséniste’, wrote Barbier—and assumed

that the late 1720s witnessed an increase in the number of supporters partly as a

reaction against the disturbing authoritarianism of government policy.

27

A recent

study of the Jansenist clergy in Paris from 1699 to 1730 provides firm grounds for

rejecting such generous speculations on the strength of the Jansenist movement

before the advent of the miracles of Saint-Médard. A clear but firm minority of

parishes had Jansenist curés and schools teaching the catechism. The research of

M.-J.Michel tends to confirm the older opinion of J.Dedieu that in spite of its

offensive during 1727–8, the Jansenist party was in disarray just before 1730. ‘After

1720 the numbers of Jansenists diminished… The movement scarcely recruited

after 1718—above all the group of important personages did not renew itself.’

28

This

important study reveals that 79 per cent of the appellant Parisian clergy from 1669

to 1730 came from the generations educated between 1650 and 1695, a figure that

POWER AND POLITICS IN OLD REGIME FRANCE

204

is broadly in line with research on Jansenism among the Oratorians.

29

Other studies

have shown that the loss of a Jansenist leader in a diocese generally meant that

resistance there crumbled and that appeals ceased. In 1729 Sainte-Barbe and Sainte

Hilaire were closed and 300 priests forbidden to practise. ‘In 1730, the refuges were

confined almost to “ghettos” under the authority and protection of an anti-

constitutionnaire curé or bishop.’

30

The laity, of course, also had access to the doctrine, the more so because it

encouraged lay interest and participation. The austere message required a high

degree of literacy for its full reception and was bound to undergo a certain

transformation of understanding as it was imparted to the less well-educated. This

in part accounts for that brief phase of popular Jansenism, the convulsionary

movement, which recalls many aspects of popular religion. It is true that supporters

of the deacon Paris and the miracles performed on his tomb at Saint-Médard had

often been educated in Jansenist schools. Unfortunately, the neat picture of a

popular religious movement is complicated by the fact that it is not also true to say

that the whole convulsionary movement was recruited from the popular classes. Of

over 600 convulsionaries and their associates identified by Maire, nearly half came

from the better off in society (shopkeepers and above), including a quarter from the

bourgeoisie, the robe and above.

31

November 1730 saw the beginning of a new stage, with the miraculous cure of

Anne Lefranc, a parishioner of the persecuted Jansenist curé of the parish of Saint

Barthélemy The parti janséniste publicised the event in March 1731 and one of its

leading theologians wrote a Dissertation on Miracles, and in particular on those which have

occurred at the tomb of M de Pâris, in the church of Saint-Médard in Paris, which marked an

important stage in the debate. It argued that the several ‘miracles’ since 1725 were

proof of divine support for the ‘defenders of the truth’ in their appeal and struggle

against the Bull Unigenitus. This dramatic turn was made even more disconcerting,

or invigorating—depending on which side you were on—in August 1731, when

people began to have convulsions on the tomb of deacon Paris. By April 1732 the

convulsionary movement had become Figurist in character, and the convulsionaries

began to prophesy. Within the parti, opinions at first differed on the status and

significance of this ‘divine intervention’, there being many theologians who were

convinced that the miracles and convulsions (whose gestures and utterances were

collected and read as Figurist prophecies) were indeed signs from God. A

contemporary text tells the story as well as any:

They began to speak of the convulsions in themselves, as a divine and

singular work, which had a sublime end, one greater, more interesting, more

wondrous than the miracles even, because the convulsions embraced the

whole destiny of the church. The allegories and figures came to their aid.

The work of the convulsions was a tableau which expressed in a tangible

way the present state of the church. The convulsionaries began to speak of

the coming of Elijah, of the return of the Jews, and of the admonition of the

Gentiles. The crowd of admirers grew daily, and the convulsionaries tried

THE PARTI FANSENISTE IN THE 1720s AND 1730s

205

hard to respond to the Public’s expectations. No more was heard of

prophecies, of figurative actions, of sublime and divinely inspired discourses,

of extraordinary ministrations [secours], and of the singular gift of bringing

about miracles of the body and the spirit.

32

The tale of the convulsionary movement has been splendidly retold by Kreiser and

Maire; suffice it to say here that several prominent convulsionaries believed

themselves to be Elijah, and many were convinced that the utterances of those

entranced were prophetic. Records were kept and served as the basis for more

Figurist interpretation.

33

But there was soon no monopoly on interpretation, and

from 1732 there was in effect lay preaching, which was very disturbing for some of

the theologians.

34

The proliferation of bizarre enactments of sexual sins, crucifixions

and delirious prophesying by the semi-literate lay men and especially women

convulsionaries such as the Augustinistes was soon perceived to be a threat.

Theologians of the parti were worried and unconvinced by the miracles themselves,

and by 1735 these were in great majority.

35

Notwithstanding the confusion that was soon created within the parti, the

evidence suggests that it was indeed the outbreak (or was it a campaign?) of

miracles which helped Jansenist curés to build up large numbers of lay

supporters in several Parisian parishes. The miracles lasted until about 1735.

They seem spontaneous in the sense that a deliberate plot is a less likely

explanation than the opportunist exploitation of the unexpected but

psychologically understandable reactions of the oppressed and disturbed

followers of deacon Paris.

36

Their date is relevant because only after 1730 did

the movement develop its popular side; the over-estimation of the strength of

the Jansenists in the years up to then has led some historians to interpret

Fleury’s declaration of 24 March 1730, which made Unigenitus into a law of

state, as an attempt to ensure respect for Vintimille and ‘the beleaguered

constitutionnaire prelates’, as Kreiser describes them.

37

In fact, until the brief

phase of popular Jansenism resulting from the miracles and convulsions in

1731, it was the Jansenist clergy who were decidedly the beleaguered party, and

the royal declaration was intended to be the coup de grâce, so to speak!

But repression and suppression was to be much harder for the government and

the constitutionnaires to carry out than anticipated. In the long run, three factors

were responsible for the transformation of the fortunes of the Jansenist movement—

although this was not to be apparent until a decade after Fleury’s death. The first

was the commitment to action inherent in the Figurist theology. The second was the

exploitation of the medium of print to further the cause. The third was the decision

to make the fullest use of the hard core of Jansenists within the Paris parlement,

among the barristers and magistrates.

Figurism has already been discussed. The second factor, printed propaganda,

was a new technique that had not been extensively used in France since the

Fronde. The fierce debate provoked by Unigenitus led to perhaps a thousand

publications in a decade.

38

An important step was taken in 1728 when it was

POWER AND POLITICS IN OLD REGIME FRANCE

206

decided to print the ecclesiastical nouvelles à la main that had circulated in

manuscript under the surplice. The Nouvelles ecclésiastiques was different because it

was an attempt to win over the opinion of a wider public to the cause. It aimed to

inform the public of the successes and misfortunes (invariably unjustly inflicted)

of the appellants, to instruct those ‘persons who cannot give all their attention to

this great business [i.e. Unigenitus and its consequences]’.

39

At the outset, the

editors boldly stated: ‘Yes, we do not intend to conceal or confuse the fact, we are

presenting to the public news of what is happening in the Church only in order to

decry the Constitution, which merits nothing less than that, and to prevent the

faithful from submitting to it in any way’.

40

The weekly broadsheet was initially financed by the two deacons and brothers

Poncet des Essarts, from a merchant family, who had studied at Saint-Magloire.

The principal organisers were Marc Poncet, d’Etemare, Boursier, Duguet, the

exiled but still active Soanen, Joubert, Boullenois, de Gennes and Coudrette; its first

editors were the abbés Boucher and Troya d’Assigny, followed by Fontaine de la

Roche in 1731. There was to be remarkable continuity in the team, and it is notable

that it was composed of the principal Figurists. Equally remarkable is the fact that

the secret organisation and distribution of the broadsheet was never discovered or

interrupted by the police. Of course, various denunciations and interrogations

enabled them to discover likely names (whence our own information), but they

were never able to find proof of authorship or involvement. The Nouvelles was even

audacious enough to publish a plan of its distribution network in an issue in 1740!

Notwithstanding the strenuous police activity, it could be found all over Paris.

41

Hérault had no better luck with that other weapon of propaganda, the satirical

engraving. During the 1730s a Jansenist iconography developed that was widely

distributed in Paris and which the ministry considered damaging. One letter to

Fleury informs him of attempts to suppress

a print that is infinitely injurious to the Council of Embrun; Your Eminence

well knows the importance of preventing the distribution of such a piece

among the Public. I myself will exercise all possible precautions to prevent it

entering Paris, but that will be infinitely more difficult than having the plates

broken in Amsterdam, and, [he adds with unsuspecting irony] we would

thereby gain the advantage of persuading the Jansenists that we are informed

of every move they make in spite of the precautions they take.

42

It is hardly possible to understand the development of the political relationship

between the ministry and the parlements without recognising the important part

Jansenism had to play in it. What was new about the Figurist Jansenism of the 1720s

and 1730s was the involvement of the lay community with it. The political

transformation of the struggle that was brought about after 1727 would not have

been possible without the laity. Both the convulsionary movement and the legalist

opposition to Unigenitus were the products of lay participation.

Although the legalist participation began in earnest in 1727,

43

it has been

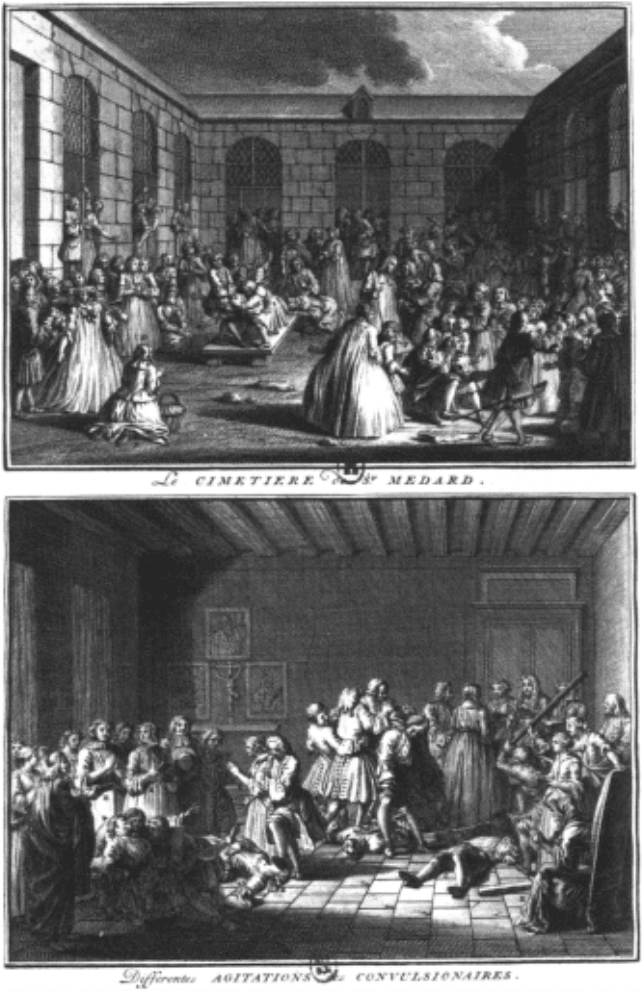

The cemetery of Saint-Médard, showing convulsionary activities (1732)