Charles M. Kozierok The TCP-IP Guide

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 801 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

Note that, perhaps ironically, no mechanism exists to report an error in a Notification

message itself. This is likely because the connection is normally terminated after such a

message is sent.

Key Concept: BGP Notification messages are used for error reporting between BGP

peers. Each message contains an Error Code field that indicates what type of

problem occurred. For certain Error Codes, an Error Subcode field provides

additional details about the specific nature of the problem. Despite these field names, Notifi-

cation messages are also used for other types of special non-error communication, such as

terminating a BGP connection.

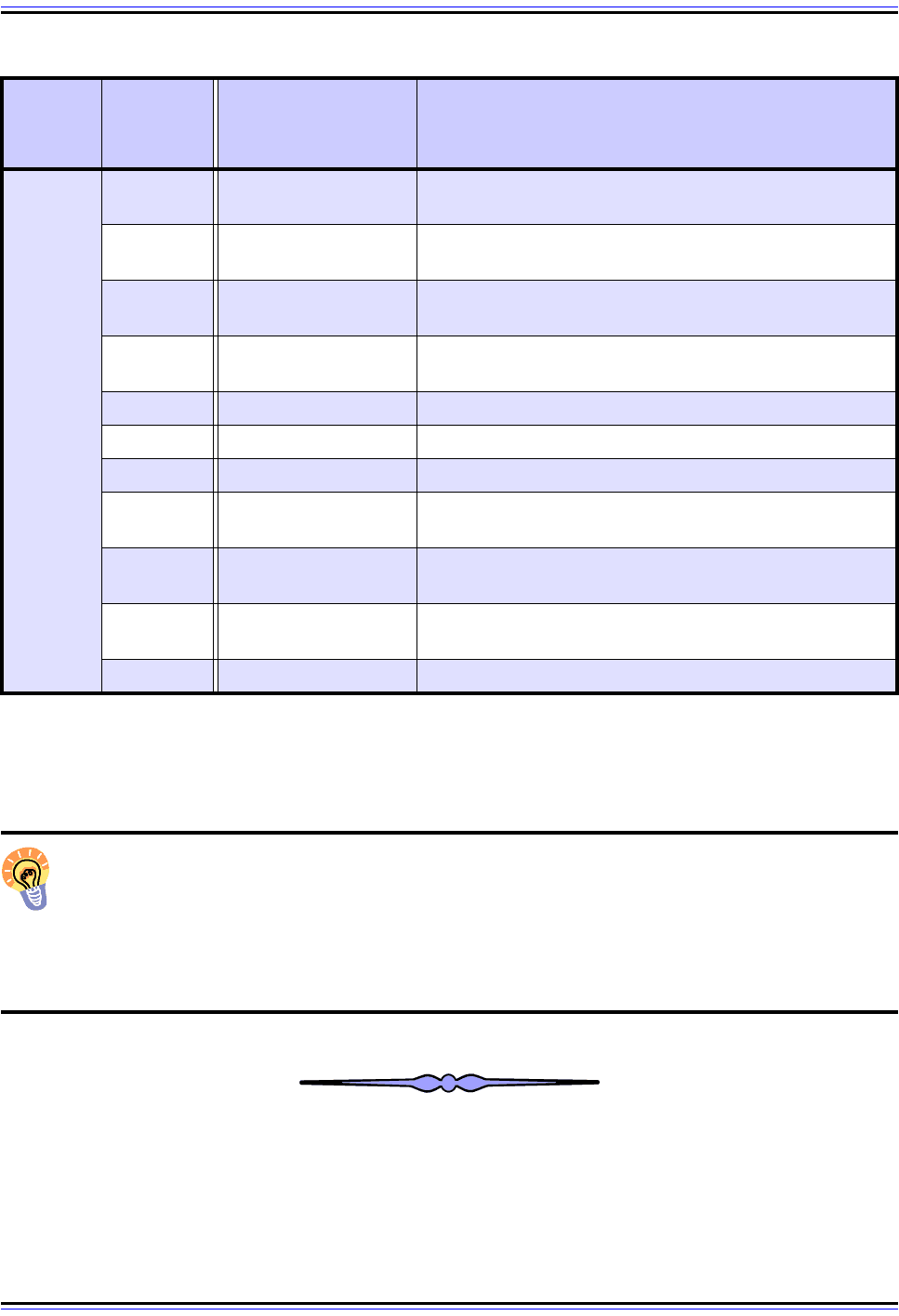

Update

Message

Error

(Error

Code 3)

1

Malformed Attribute

List

The overall structure of the message's path attributes is

incorrect, or an attribute has appeared twice.

2

Unrecognized Well-

Known Attribute

One of the mandatory well-known attributes was not

recognized.

3

Missing Well-Known

Attribute

One of the mandatory well-known attributes was not

specified.

4 Attribute Flags Error

An attribute has a flag set to a value that conflicts with

the attribute's type code.

5 Attribute Length Error The length of an attribute is incorrect.

6 Invalid Origin Attribute The Origin attribute has an undefined value.

7 AS Routing Loop A routing loop was detected.

8

Invalid Next_Hop

Attribute

The Next_Hop attribute is invalid.

9

Optional Attribute

Error

An error was detected in an optional attribute.

10 Invalid Network Field

The Network Layer Reachability Information field is

incorrect.

11 Malformed AS_Path The AS_Path attribute is incorrect.

Table 144: BGP Notification Message Error Subcodes (Page 2 of 2)

Error

Type

Error

Subcode

Value

Subcode Name Description

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 802 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

TCP/IP Exterior Gateway Protocol (EGP)

Routing in the early Internet was done using a small number of centralized core routers that

maintained complete information about network reachability on the Internet. They

exchanged information using the historical interior routing protocol, the Gateway-to-

Gateway Protocol (GGP). Around the periphery of this core were located other non-core

routers, sometimes standalone and sometimes collected into groups. These exchanged

network reachability information with the core routers using the first TCP/IP exterior routing

protocol: the Exterior Gateway Protocol (EGP).

History and Development

Like its interior routing counterpart GGP, EGP was developed by Internet pioneers Bolt,

Beranek and Newman (BBN) in the early 1980s. It was first formally described in an Internet

standard in RFC 827, Exterior Gateway Protocol (EGP), published in October 1982. This

draft document was superseded in April 1984 by RFC 904, Exterior Gateway Protocol

Formal Specification. Like GGP, EGP is now considered obsolete, having been replaced by

the Border Gateway Protocol (BGP). However, also like GGP, it is an important part of the

history of TCP/IP routing, so it is worth examining briefly.

Note: As I explained in the introduction to this overall section on TCP/IP routing

protocols, routers were in the past often called gateways. As such, exterior routing

protocols were “exterior gateway protocols”. The EGP protocol discussed here is a

specific instance of an exterior gateway protocol, for which the abbreviation is also EGP.

Thus, you may occasionally see BGP also called an “exterior gateway protocol” or an

“EGP”, which is the generic use of this term.

Overview of Operation

EGP is responsible for communication of network reachability information between neigh-

boring routers, which may or may not be in different autonomous systems. The operation of

EGP is somewhat similar to that of BGP. Each EGP router maintains a database of infor-

mation regarding what networks it can reach and how to reach them. It sends this

information out on a regular basis to each router to which it is directly connected. Routers

receive these messages and update their routing tables, and then use this new information

to update other routers. Information about how to reach each network propagates across

the entire internetwork.

Routing Information Exchange Process

The actual process of exchanging routing information involves several steps to discover

neighbors and then set up and maintain communications. Briefly, the steps are:

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 803 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

1. Neighbor Acquisition: Each router attempts to establish a connection to each of its

neighboring routers by sending Neighbor Acquisition Request messages. A neighbor

hearing a request can respond with a Neighbor Acquisition Confirm to say that it

recognized the request and wishes to connect. It may reject the acquisition by replying

with a Neighbor Acquisition Refuse message. For an EGP connection to be estab-

lished between a pair of neighbors, each must first successfully acquire the other with

a Confirm message.

2. Neighbor Reachability: After acquiring a neighbor, a router checks to make sure the

neighbor is reachable and functioning properly on a regular basis. This is done by

sending an EGP Hello message to each neighbor for which a connection has been

established. The neighbor replies with an I Heard You (IHU) message. These

messages are somewhat analogous to the BGP Keepalive message, but are used in

matched pairs.

3. Network Reachability Update: A router sends Poll messages on a regular basis to

each of its neighbors. The neighbor responds with an Update message, which

contains details about the networks that it is able to reach. This information is used to

update the routing tables of the device that sent the Poll.

A neighbor can decide to terminate a connection (called neighbor de-acquisition) by

sending a Cease message; the neighbor responds with a Cease-ack (acknowledge)

message.

As I mentioned earlier, the primary function in the early Internet was to connect peripheral

routers or groups of routers to the Internet core. It was therefore designed under the

assumption that the internetwork was connected as a hierarchical tree, with the core as the

root. EGP was not designed to handle an arbitrary topology of autonomous systems like

BGP, and cannot guarantee the absence of routing loops if such loops exist in the intercon-

nection of neighboring routers. This is part of why BGP needed to be developed as the

Internet moved to a more arbitrary structure of autonomous system connections; it has now

entirely replaced EGP.

Error Reporting

An Error message is also defined, which is similar to the BGP Notification message in role

and structure. It may be sent by a neighbor in response to receipt of an EGP message

either when the message itself has a problem (such as a bad message length or unrecog-

nized data in a field) or to indicate a problem in how the message is being used (such as

receipt of Hello or Poll messages at a rate deemed excessive). Unlike the BGP Notification

message, an EGP router does not necessarily close the connection when sending an Error

message.

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 804 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

Key Concept: The Exterior Gateway Protocol (EGP) was the first TCP/IP exterior

routing protocol and was used with GGP on the early Internet. It functions in a

manner similar to BGP: an EGP router makes contact with neighboring routers and

exchanges routing information with them. A mechanism is also provided to maintain a

session and report errors. EGP is more limited than BGP in capability and is now

considered a historical protocol.

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 805 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

TCP/IP Transport Layer Protocols

The first three layers of the OSI Reference Model—the physical layer, data link layer and

network layer—are very important layers for understanding how networks function. The

physical layer moves bits over wires; the data link layer moves frames on a network; the

network layer moves datagrams on an internetwork. Taken as a whole, they are the parts of

a protocol stack that are responsible for the actual “nuts and bolts” of getting data from one

place to another.

Immediately above these we have the fourth layer of the OSI Reference Model: the

transport layer, called the host-to-host transport layer in the TCP/IP model. This layer is

interesting in that it resides in the very architectural center of the model. Accordingly, it

represents an important transition point between the hardware-associated layers below it

that do the “grunt work”, and the layers above that are more software-oriented and abstract.

Protocols running at the transport layer are charged with providing several important

services to enable software applications in higher layers to work over an internetwork. They

are typically responsible for allowing connections to be established and maintained

between software services on possibly distant machines. Perhaps most importantly, they

serve as the bridge between the needs of many higher-layer applications to send data in a

reliable way without needing to worry about error correction, lost data or flow management,

and network-layer protocols, which are often unreliable and unacknowledged. Transport

layer protocols are often very tightly-tied to the network layer protocols directly below them,

and designed specifically to take care of functions that they do not deal with.

In this section I describe transport layer protocols and related technologies used in the

TCP/IP protocol There are two main protocols at this layer; the Transmission Control

Protocol (TCP) and the User Datagram Protocol (UDP). I also discuss how transport-layer

addressing is done in TCP/IP in the form of ports and sockets.

Note: It may seem strange that I have only one subsection here, the one that

covers TCP and UDP. This is a result of the fact that The TCP/IP Guide is

excerpted from a larger networking reference.

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 806 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) and User Datagram

Protocol (UDP)

TCP/IP is the most important internetworking protocol suite in the world; it is the basis for

the Internet, and the “language” spoken by the vast majority of the world's networked

computers. TCP/IP includes a large set of protocols that operate at the network layer and

above. The suite as a whole is anchored at layer three by the Internet Protocol (IP), which

many people consider the single most important protocol in the world of networking.

Of course, there's a bit of architectural distance between the network layer and the applica-

tions that run at the layers well above. While IP is the protocol that performs the bulk of the

functions needed to make an internetwork, it does not include many capabilities that are

needed by applications. In TCP/IP these tasks are performed by a pair of protocols that

operate at the transport layer: the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) and the User

Datagram Protocol (UDP).

Of these two, TCP gets by far the most attention. It is the transport layer protocol that is

most often associated with TCP/IP, and, well, its name is right there, “up in lights”. It is also

the transport protocol used for many of the Internet's most popular applications, while UDP

gets second billing. However, TCP and UDP are really peers that play the same role in

TCP/IP. They function very differently and provide different benefits and drawbacks to the

applications that use them, which makes them both important to the protocol suite as a

whole. The two protocols also have certain areas of similarity, which makes it most efficient

that I describe them in the same overall section, highlighting where they share character-

istics and methods of operation, as well as where they diverge.

In this section I provide a detailed examination of the two TCP/IP transport layer protocols:

the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) and the User Datagram Protocol (UDP). I begin

with a quick overview of the role of these two protocols in the TCP/IP protocol suite, and a

discussion of why they are both important. I describe the method that both protocols employ

for addressing, using transport-layer ports and sockets. I then have two detailed sections

for each of UDP and TCP. I conclude with a summary quick-glance comparison of the two.

Incidentally, I describe UDP before TCP for a simple reason: it is simpler. UDP operates

more like a classical message-based protocol, and in fact is more similar to IP itself than is

TCP. This is the same reason why the section on TCP is much larger than that covering

UDP: TCP much more complex and does a great deal more than UDP.

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 807 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

TCP and UDP Overview and Role In TCP/IP

The transport layer in a protocol suite is responsible for a specific set of functions. For this

reason, one might expect that the TCP/IP suite would have a single main transport protocol

to perform those functions, just as it has IP as its core protocol at the network layer. It is a

curiosity, then, that there are two different widely-used TCP/IP transport layer protocols.

This arrangement is probably one of the best examples of the power of protocol layering—

and hence, an illustration that it was worth all the time you spent learning to understand that

pesky OSI Reference Model. ☺

Differing Transport Layer Requirements in TCP/IP

Let's start with a look back at layer three. In my overview of the key operating character-

istics of the Internet Protocol, I described several important limitations of how IP works. The

most important of these are that IP is connectionless, unreliable and unacknowledged. Data

is sent over an IP internetwork without first establishing a connection, using a “best effort”

paradigm. Messages usually get where they need to go, but there are no guarantees, and

the sender usually doesn't even know if the data got to its destination.

These characteristics present serious problems to software. Many, if not most, applications

need to be able to count on the fact that the data they send will get to its destination without

loss or error. They also want the connection between two devices to be automatically

managed, with problems such as congestion and flow control taken care of as needed.

Unless some mechanism is provided for this at lower layers, every application would need

to perform these jobs, which would be a massive duplication of effort.

In fact, one might argue that establishing connections, providing reliability, and handling

retransmissions, buffering and data flow is sufficiently important that it would have been

best to simply build these abilities directly into the Internet Protocol. Interestingly, that was

exactly the case in the early days of TCP/IP. “In the beginning” there was just a single

protocol called “TCP” that combined the tasks of the Internet Protocol with the reliability and

session management features just mentioned.

There's a big problem with this, however. Establishing connections, providing a mechanism

for reliability, managing flow control and acknowledgments and retransmissions: these all

come at a cost: time and bandwidth. Building all of these capabilities into a single protocol

that spans layers three and four would mean all applications got the benefits of reliability,

but also the costs. While this would be fine for many applications, there are others that both

don't need the reliability, and “can't afford” the overhead required to provide it.

The Solution: Two Very Different Transport Protocols

Fixing this problem was simple: let the network layer (IP) take care of basic data movement

on the internetwork, and define two protocols at the transport layer. One would provide a

rich set of services for those applications that need that functionality, with the understanding

that some overhead was required to accomplish it. The other would be simple, providing

little in the way of classic layer-four functions, but it would be fast and easy to use. Thus, the

result of two TCP/IP transport-layer protocols:

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 808 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

☯ Transmission Control Protocol (TCP): A full-featured, connection-oriented, reliable

transport protocol for TCP/IP applications. TCP provides transport-layer addressing to

allow multiple software applications to simultaneously use a single IP address. It

allows a pair of devices to establish a virtual connection and then pass data bidirec-

tionally. Transmissions are managed using a special sliding window system, with

unacknowledged transmissions detected and automatically retransmitted. Additional

functionality allows the flow of data between devices to be managed, and special

circumstances to be addressed.

☯ User Datagram Protocol (UDP): A very simple transport protocol that provides

transport-layer addressing like TCP, but little else. UDP is barely more than a

“wrapper” protocol that provides a way for applications to access the Internet Protocol.

No connection is established, transmissions are unreliable, and data can be lost.

By means of analogy, TCP is a fully-loaded luxury performance sedan with a chauffeur and

a satellite tracking/navigation system. It provides lots of frills and comfort, and good perfor-

mance. It virtually guarantees you will get where you need to go without any problems, and

any concerns that do arise can be corrected. In contrast, UDP is a stripped-down race car.

Its goal is simplicity and speed, speed, speed; everything else is secondary. You will

probably get where you need to go, but hey, race cars can be finicky to keep operating.

Key Concept: To suit the differing transport requirements of the many TCP/IP appli-

cations, two TCP/IP transport layer protocols exist. The Transmission Control

Protocol (TCP) is a full-featured, connection-oriented protocol that provides acknowl-

edged delivery of data while managing traffic flow and handling issues such as congestion

and transmission loss. The User Datagram Protocol (UDP), in contrast, is a much simpler

protocol that concentrates only on delivering data, to maximize the speed of communication

when the features of TCP are not required.

Applications of TCP and UDP

Having two transport layer protocols with such complementary strengths and weaknesses

provides considerable flexibility to the creators of networking software:

☯ TCP Applications: Most “typical” applications need the reliability and other services

provided by TCP, and don't care about loss of a small amount of performance to

overhead. For example, most applications that transfer files or important data between

machines use TCP, because loss of any portion of the file renders the entire thing

useless. Examples include such well-known applications as the Hypertext Transfer

Protocol (HTTP) used by the World Wide Web (WWW), the File Transfer Protocol

(FTP) and the Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP). I describe TCP applications in

more detail in the TCP section.

☯ UDP Applications: I'm sure you're thinking: “what sort of application doesn't care if its

data gets there, and why would I want to use it?” You might be surprised: UDP is used

by lots of TCP/IP protocols. UDP is a good match for applications in two circum-

stances. The first is when the application doesn't really care if some of the data gets

lost; streaming video or multimedia is a good example, since one lost byte of data

won't even be noticed. The other is when the application itself chooses to provide

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 809 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

some other mechanism to make up for the lack of functionality in UDP. Applications

that send very small amounts of data, for example, often use UDP under the

assumption that if a request is sent and a reply is not received, the client will just send

a new request later on. This provides enough reliability without the overhead of a TCP

connection. I discuss some common UDP applications in the UDP section.

Key Concept: Most classical applications, especially ones that send files or

messages, require that data be delivered reliably, and therefore use TCP for

transport. Applications using UDP are usually those where loss of a small amount of

data is not a concern, or that use their own application-specific procedures for dealing with

potential delivery problems that TCP handles more generally.

In the next few sections we'll first examine the common transport layer addressing scheme

used by TCP and UDP, and then look at each of the two protocols in detail. Following these

sections is a summary comparison to help you see at a glance where the differences lie

between TCP and UDP. Incidentally, if you want a good “real-world” illustration of why

having both UDP and TCP is valuable, consider message transport under the Domain

Name System (DNS), which actually uses UDP for certain types of communication and

TCP for others.

Before leaving the subject of comparing UDP and TCP, I want to explicitly point out that

even though TCP is often described as being slower than UDP, this is a relative

measurement. TCP is a very well-written protocol that is capable of highly efficient data

transfers. It is only slow compared to UDP because of the overhead of establishing and

managing connections. The difference can be significant, but is not enormous, so keep that

in mind.

The TCP/IP Guide - Version 3.0 (Contents) ` 810 _ © 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

TCP/IP Transport Layer Protocol (TCP and UDP) Addressing: Ports

and Sockets

Internet Protocol (IP) addresses are the universally-used main form of addressing on a

TCP/IP network. These network-layer addresses uniquely identify each network interface,

and as such, serve as the mechanism by which data is routed to the correct network on the

internetwork, and then the correct device on that network. What some people don't realize,

however, is that there is an additional level of addressing that occurs at the transport layer

in TCP/IP, above that of the IP address. Both of the TCP/IP transport protocols, TCP and

UDP, use the concepts of ports and sockets for virtual software addressing, to enable the

function of many applications simultaneously on an IP device.

In this section I describe the special mechanism used for addressing in both TCP and UDP.

I begin with a discussion of TCP/IP application processes, including the client/server nature

of communication, which provides a background for explaining how ports and sockets are

used. I then give an overview of the concept of ports, and how they enable the multiplexing

of data over an IP address. I describe the way that port numbers are categorized in ranges,

and assigned to server processes for common applications. I explain the concept of

ephemeral port numbers used for clients. I then discuss sockets and their use for

connection identification, including the means by which multiple devices can talk to a single

port on another device. I then provide a summary table of the most common well-known

and registered port numbers.

TCP/IP Processes, Multiplexing and Client/Server Application Roles

I believe the most sensible place to start learning about how the TCP/IP protocol suite

works is by examining the Internet Protocol (IP) itself, and the support protocols that

function in tandem with it at the network layer. IP is the foundation upon which most of the

rest of TCP/IP is built. It is the mechanism by which data is packaged and routed throughout

a TCP/IP internetwork.

It makes sense, then, that when we examine the operation of TCP/IP from the perspective

of the Internet Protocol, we talk very generically about sending and receiving datagrams. To

the IP layer software that sends and received IP datagrams, the higher-level application

they come from and go to is really unimportant: to IP, “a datagram is a datagram”, pretty

much. All datagrams are packaged and routed in the same way, and IP is mainly concerned

with lower-level aspects of moving them between devices in an efficient manner.

It's important to remember, however, that this is really an abstraction, for the convenience

of describing layer three operation. It doesn't consider how datagrams are really generated

and used above layer three. Layer four represents a transition point between the OSI model

hardware-related layers (one, two and three) and the software-related layers (five to

seven). This means the TCP/IP transport layer protocols, TCP and UDP, do need to pay

attention to the way that software uses TCP/IP, even if IP really does not.