Cutle, Timothy: On Voice Exchange

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

221

Timothy Cutler On Voice Exchanges

event (Example 25). This looks promising on paper, although one must

rationalize the absence of the subdominant (m. 16) from the deeper har-

monic motion of the movement. As with some previous examples, justifica-

tion is derived from the intoxicating influence of voice exchanges. c major,

VII in the key of D minor, receives moderately strong cadential emphasis

in mm. 11–12. After moving to G minor, the next sonority rings a familiar

bell—another c-major harmony in m. 17, this time with an additional sev-

enth, B≤, that pushes toward III (F major). Unifying these two moments is

an exchange of voices, c and E, in mm. 12 and 17. The two voices are not

literally the same—the upper line is the soprano in m. 12 and an inner voice

in m. 17—yet this exchange and the prolongation of VII, or V of III, could

explain the purpose of the intervening music. The G-minor harmony would

support a descending passing tone, D, in a middle voice and facilitate the

unfolding of VII in the bass (c–G–E), which represents a linear expression of

the vertical harmony prolonged from mm. 12–17. If this analysis still does not

rescue the proposed voice exchange in mm. 21–22, it does demonstrate that

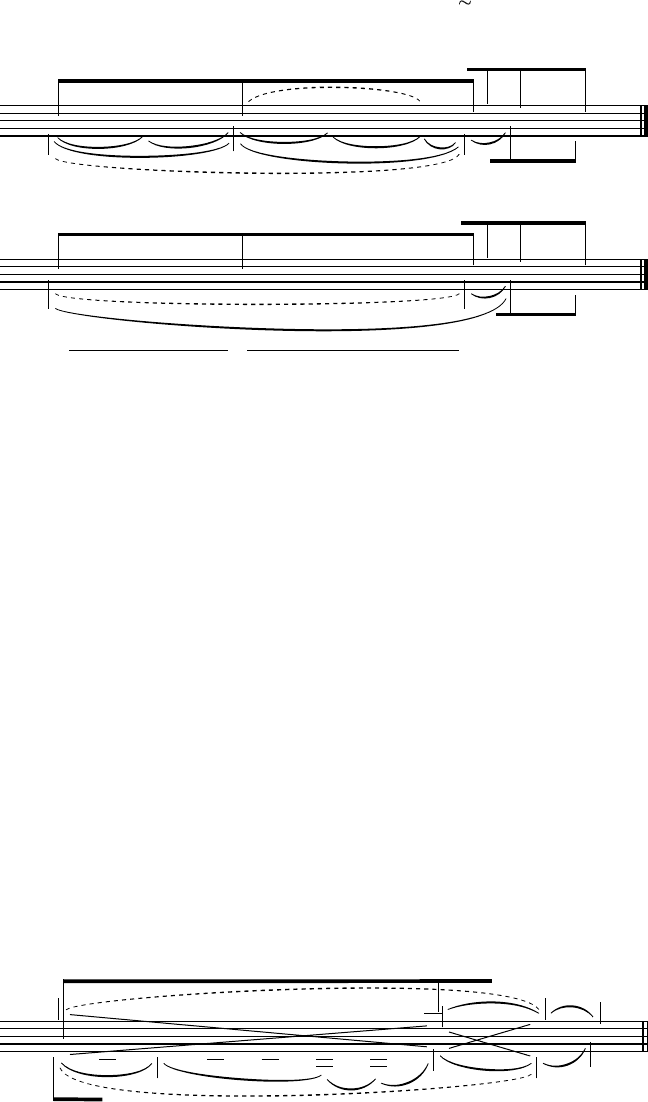

the 5–6 motive remains a central fixture. recalling the 5–6 motions in mm. 1

and 3, we find it in mm. 18–23 as well as a new parallelism: The 5–6 motive

cutler_23 (section) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/2_cutler Wed May 5 12:09 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 1 of 1 pages

Š

−

Ł

Ł

ŁŁ

Ł

²

Ł

Ł

Ł

¦

Ł

Ł

²

Ł

Ł

Ł

²

Ł−

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

−

¦

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

¦

²

Ł

Ł

Ł

ð

¦

ð

ð

ð

ð

Š

−

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł²

Ł

Ł

Ł

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

m. 18

5

IIId:

65

19

65

20 21 22 23

I

6

V

24

I

III

5

²

56

VI

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Cutler Example 23

Example 23. Bach, BWV 1004, Sarabande, mm. 18–24 (hypothetical voice-leading graph)

cutler_24 (section) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/2_cutler Wed May 5 12:09 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 1 of 1 pages

Š

−

Ł

ð

ð

Ł²

Ł

Ł¦

Ł

Ł

Ł

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

²

Id:

m. 1 7 8

V

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Cutler Example 24

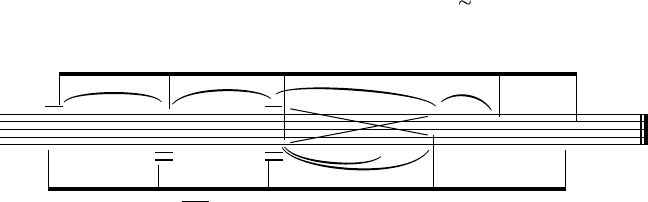

Example 24. Bach, BWV 1004, Sarabande, mm. 1–8 (twin voice exchanges)

222

JOUrnAl of MUSIc ThEOrY

of m. 1 (A–B≤) is mirrored by a longer 5–6 progression in mm. 1–11 (A–BΩ).

When the Sarabande reaches the second ending, Bach does not forget this

idea: B≤ and BΩ return prominently in the bass.

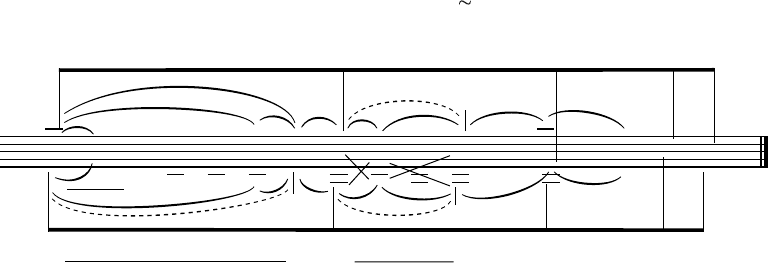

While there are aspects of Example 25 that are genuinely pleasing, it

represents, as does Example 23, an analytical fantasy. Ultimately, it reflects

not so much the Sarabande itself but one’s zeal for finding large-scale voice

exchanges, irrespective of their functionality. Simply put, Example 25 does

not listen to the music. The emphatic G-minor authentic cadence in m. 16

does not sound like a lesser structural goal than the weaker c-major cadence

in m. 12. Instead, a better interpretation highlights G minor as a place of

temporary repose along the harmonic route of the Sarabande. The path from

opening tonic to subdominant in m. 16 reveals more motivic connections

(Example 26). The 5–6 motion in m. 1 is replicated over the sixteen-measure

span, with inner-voice A completing a large-scale ascent to B≤. Similarly, the

descent of the Urlinie from 5

ˆ

to 4

ˆ

features passing motion to an inner voice F≥,

illustrated by the third measure of Example 26. This idea is then nested within

itself, as shown in the fifth and sixth measures of Example 26.

cutler_25 (section) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/2_cutler Wed May 5 12:10 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 1 of 1 pages

Š

−

ð

Ł

Ł

ð

Ł

Ł

�

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

¦

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

−

Ł

Ł

Ł

ð

Ł

Ł

ð

Ł²

Ł

ð

ð

ð

ð

m. 1

5

Id:

8

¦

6

11 12

(VII)

8

16

7

17

III

5

18 20 23

6

V

24

I

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Cutler Example 25

Example 25. Bach, BWV 1004, Sarabande, mm. 1–24 (hypothetical voice-leading graph)

cutler_26 (section) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/2_cutler Wed May 5 12:10 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 1 of 1 pages

Š

−

ð

Ł

ð

ð

Ł

ð

ð

Ł

Ł

ð

Ł

Ł

²

ð

Ł

ð

ð

Ł

Ł

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

²

ð

Ł

Ł

ð

ð

Ł

Ł

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł²

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

²

ð

Ł

Ł

ð

Š

−

ð

Ł

Ł

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

²

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

²

ð

Ł

Ł

ð

ð

Ł

Ł

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

¦

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

²

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

−

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

²

ð

Ł

Ł

ð

Id:

m. 1

IV

16 1

CP

15 16 1

P

13 15 16 1

CP

13 15 16

1

5

P

12

5

13 15 16 1

5

11

¦

6

12 13 15 16

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Cutler Example 26

Example 26. Bach, BWV 1004, Sarabande, mm. 1–16

223

Timothy Cutler On Voice Exchanges

Perceiving G minor as a principal structural moment in the Sarabande

leads to another long-range relationship: the lowest pitch in m. 16, the vio-

lin’s open G-string, forms a strong aural association with the bass G of the

neapolitan in m. 22. This points to another form of the 5–6 motive, with

the fifth of the G-minor harmony rising to a flattened sixth, and defines

mm. 16–22 as an area of predominant expansion. After this lengthy and

deep-level accumulation of predominant tension, it may not seem appropriate

for the neapolitan to resolve through VII

4

3

to a somewhat unsteady I

6

chord.

It is here that the concept of the inverted cadential six-four is so valuable,

because the “I

6

” in m. 23 is not a first-inversion tonic harmony but instead

a chord possessing dominant function. This permits the prolongation of IV,

with its chromatic 5–6 offshoot ≤II

6

, to progress to its desired location, the

dominant (Example 27).

29

What does all of this mean for the original voice-exchange hypothesis

in mm. 21–22? In the speculative analyses shown in Examples 23 and 25, this

pitch swap was deemed unsound because the starting and ending points of

the exchange did not share similar harmonic function. however, these inter-

pretations ignore another pertinent clue that occurs during the first eight

measures—the twin voice exchanges that coincide with the bass’s descend-

ing octave. having affiliated mm. 16 and 22, which both feature prominent

GΩ’s in the highest and lowest registers and bring about a 5–6 motion in an

upper voice, one can compare the downbeats of mm. 22 and 21 to uncover

another connection to m. 16. Implied on the downbeat of m. 16 is a B≤ that

occurs literally a few beats later. These pitches in m. 16, G and B≤, form a

voice exchange with B≤ and G in m. 21, which in turn trade pitches with

m. 22, producing a twin voice exchange to complement the same idea in

mm. 1–8 (Example 28).

What remains is to clarify the harmony on the downbeat of m. 21. It

turns out that its surface role is an illusion, and its function on a deeper

level is quite different (Example 29). c≥ and E, which generate the “VII

4

2

”

29 The explicitness the voice exchange associated with the

inverted cadential six-four depends on one’s interpretation

of the third beat of m. 23. If one hears F remaining in the

upper voice when beat 3 arrives, as does Schumann in his

piano accompaniment for the Sarabande, one can depict

an implied voice exchange as shown in Example 27. If one

hears E when beat 3 enters, creating a 4–3 suspension in an

inner voice, the exchange is more conceptual in nature.

cutler_27 (section) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/2_cutler Wed May 5 12:10 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 1 of 1 pages

Š

−

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

ð

Ł

Ł²

ð

Ł

Ł

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

−

Ł

Ł

ð

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

ð

ð

ð

ð

(

)

(

)

Id:

m. 1 15 16

IV

5

22

−

6

23

V

6

4

5

²

I

24

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Cutler Example 27

Example 27. Bach, BWV 1004, Sarabande, mm. 1–24

224

JOUrnAl of MUSIc ThEOrY

chord in m. 21, are the products of contrapuntal elaboration and obscure the

subdominant underpinnings of these measures. The label “VII

4

2

” is operational

only on the surface of the music. The end result is a large-scale exchange

of pitches spanning mm. 16–21 that complements the voice exchange in

mm. 21–22. The voice exchange in mm. 21–22 is indeed valid,

30

and it enhances

an interpretation that reflects some of the most salient features of the com-

position: small- and large-scale demonstrations of the 5–6 motive, twin voice

exchanges in mm. 1–8 and 16–22, an early tonicization of G minor (mm. 4–5)

foreshadowing a more prominent move to the subdominant (m. 16), and an

overall harmonic motion that satisfies the musical contours of the composi-

tion rather than an infatuation with intriguing yet dubious examples of voice

exchanges (Example 30).

cutler_28 (section) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/2_cutler Wed May 5 12:10 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 1 of 1 pages

Š

−

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

²

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

−

m. 16

IV

5

d:

21

−

6

22

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Cutler Example 28

Example 28. Bach, BWV 1004, Sarabande, mm. 16–22 (twin voice exchanges)

cutler_29 (section) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/2_cutler Wed May 5 12:10 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 1 of 1 pages

Š

−

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł−

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

−

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

²

Ł

Ł

Ł−

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

²

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

−

Š

−

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

²

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

−

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

²

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

−

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

²

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

−

m. 16

5–6 motion

22 16

arpeggiation

21 22

IV

5

N

−

6

IV

5

N

P

−

6

IV

5

soprano harmonizes

−

6

IV

5

fourth voice added;

voice exchanges emerge

−

6

16

IV

5

passing

chord

20 2121 22

−

6

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Cutler Example 29

Example 29. Bach, BWV 1004, Sarabande, mm. 16–22

30 Since analysis shows that the voice exchange in

mm. 21–22 is operative, it brings into question the habit of

many violinists who interpret the latter two beats of m. 21

as a quasi cadence by applying heavy doses of morendo

rather than pressing through the passing six-four toward the

Neapolitan.

225

Timothy Cutler On Voice Exchanges

Conclusion

hunting recklessly for pitch swaps can result in analytical delirium. handled

with care, the pursuit of voice exchanges leads to new depths of musical

understanding. It establishes that what one sees and hears is not always equiva-

lent, that small-scale ideas may be ingeniously replicated over longer spans of

musical time, that instances of chromatic “chaos” can be understood within

a diatonic framework, and that the study of long-range voice exchanges is

one means of enhancing Fernhören (“distance-hearing”) (Furtwängler 1955,

201–2). Whether implied or explicit, chromatic or diatonic, local or long-

range, comprehending voice exchanges makes us not just better theorists, but

deeper listeners and more profound musicians.

Works Cited

Abraham, Gerald. 1973. Chopin’s Musical Style. new York: Oxford University Press.

Anson-cartwright, Mark. 1998. “The Development Section in haydn’s late Instrumental

Works.” Ph.D. diss., city University of new York.

cadwallader, Allen. 1992. “More on Scale Degree Three and the cadential Six-Four.” Journal

of Music Theory 36: 187–98.

cadwallader, Allen and David Gagné. 1998. Analysis of Tonal Music: A Schenkerian Approach. new

York: Oxford University Press.

Damschroder, David. 2008. Thinking about Harmony: Historical Perspectives on Analysis. new York:

cambridge University Press.

Delong, Kenneth. 1991. “roads Taken and retaken: Foreground Ambiguity in chopin’s Pre-

lude in A-flat, op. 28, no. 17.” Canadian University Music Review 11/1: 34–49.

Eigeldinger, Jean-Jacques. 1986. Chopin: Pianist and Teacher as Seen by His Pupils. new York:

cambridge University Press.

Furtwängler, Wilhelm. 1955. Ton und Wort. Wiesbaden: Brockhaus.

Galand, Joel. 1995. “Form, Genre, and Style in the Eighteenth-century rondo.” Music Theory

Spectrum 17: 27–52.

Kamien, roger and naphtali Wagner. 1997. “Bridge Themes within a chromaticized Voice

Exchange in Mozart Expositions.” Music Theory Spectrum 19: 1–12.

Kresky, Jeffrey. 1994. A Reader’s Guide to the Chopin Preludes. Westport, cT: Greenwood Press.

cutler_30 (section) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/2_cutler Wed May 5 12:10 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 1 of 1 pages

Š

−

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

²

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

¦

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

¦

Ł

Ł

Ł²

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

−

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

²

ð

Ł

Ł

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

²

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

¦

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

−Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

¦

²

Ł

Ł

ð

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

²

Ł

Ł

Ł

ð

Ł

ð

²

ð

ð

()

(

)

m. 1

Id:

9

5

8

¦

6

11 12 13 15

8

16

IV

5

21 22

−

6

V

6

4

23

5

²

24

I

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Cutler Example 30

Example 30. Bach, BWV 1004, Sarabande, mm. 1–24

226

JOUrnAl of MUSIc ThEOrY

neumeyer, David and Susan Tepping. 1992. A Guide to Schenkerian Analysis. Englewood cliffs,

nJ: Prentice-hall.

Parker, Beverly. 1985. “Voice-Exchange from De Musica Mensurabili Posito to The New Grove Dic-

tionary.” South African Journal of Musicology 5/1: 31–40.

rothstein, William. 1991. “On Implied Tones.” Music Analysis 10: 289–328.

———. 2005. “like Falling Off a log: rubato in chopin’s Prelude in A-flat major (op. 28,

no. 17).” Music Theory Online 11/1. http://mto.societymusictheory.org/issues/mto.05.11.1

/toc.11.1.html.

———. 2006. “Transformations of cadential Formulae in the Music of corelli and his Suc-

cessors.” In Essays from the Third International Schenker Symposium, ed. Allen cadwallader,

245–78. new York: Georg Olms.

Salzer, Felix and carl Schachter. 1969. Counterpoint in Composition. new York: McGraw-hill.

Schachter, carl. 1983. “The First Movement of Brahms’s Second Symphony: The Opening

Theme and Its consequences.” Music Analysis 2: 55–68.

Schenker, heinrich. 1994. “The largo of Bach’s Sonata no. 3 for Solo Violin.” In The Mas-

terwork in Music, Vol. 1, ed. William Drabkin, trans. John rothgeb, 31–38. new York:

cambridge University Press.

———. 1997. “Beethoven’s Third Symphony: Its True content Described for the First Time.”

In The Masterwork in Music, Vol. 3, ed. Ian Bent, trans. Derrick Puffett and Alfred clay-

ton, 10–68. new York: cambridge University Press.

Sobaskie, James. 2007–8. “Precursive Prolongation in the Préludes of chopin.” Journal for the

Society of Musicology in Ireland 3: 25–61.

Suurpää, lauri. 1999. “Programmatic Aspects of the Second Sonata of haydn’s Seven Last

Words.” Theory and Practice 24: 29–55.

Wen, Eric. 1999. “Bass-line Articulations of the Urlinie.” In Schenker Studies 2, ed. carl Schachter

and hedi Siegel, 276–97. new York: cambridge University Press.

Timothy Cutler is professor of music theory at the Cleveland Institute of Music. He is the creator of

the Internet Music Theory Database (www.musictheoryexamples.com), a collection of roughly 1,500

categorized examples of tonal harmonic and contrapuntal techniques.