Deal W.E. Handbook To Life In Medieval And Early Modern Japan

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Kyoto shugo (Kyoto military governor) The

position of Kyoto military governor was established

at the beginning of the Kamakura shogunate. The

governor’s role was to oversee the affairs of the

imperial court on behalf of the shogunate. This

position was replaced by the Rokuhara tandai in

1221.

Rokuhara tandai (Rokuhara deputies) The office

of Rokuhara tandai (shogunal deputies located in the

Rokuhara district of Kyoto) was established in 1221

to replace the office of Kyoto shugo as supervisors of

political, military, and legal matters. The Rokuhara

tandai were responsible not only for overseeing

Kyoto, but also affairs in the southwestern part of

Japan. This position was created as the direct effect

of Emperor Go-Toba’s attempt, known as the Jokyu

Disturbance, to overthrow the shogunate and

reestablish direct imperial rule. After Go-Toba’s

defeat, the Rokuhara tandai was set up in part to

ensure that such threats to shogunal power did not

occur again.

Chinzei bugyo (Kyushu commissioner) This

position was established by the Kamakura shogu-

nate. The shogunate appointed two commissioners

to oversee local Kyushu matters, especially the activ-

ities of Minamoto vassals.

Chinzei tandai (Kyushu deputies) Like the

Rokuhara tandai, the Chinzei tandai were overseers

of political, military, and legal matters. Their sphere

of responsibility was Kyushu. This office was estab-

lished in 1293 in response to ongoing concerns that

the Mongols would make additional attempts to

invade Japan through Kyushu ports.

Oshu sobugyo (Oshu general commissioner)

This office was established by the Kamakura shogu-

nate at the beginning of the medieval period in an

area of northeastern Japan known as Oshu (island of

Honshu). This region was the domain of a warrior

branch of the Fujiwara family known as the Oshu

Fujiwara who ruled the area with little intervention

from the imperial court during the Heian period. In

1189, Minamoto no Yoritomo, fearing the power of

this domain, attacked and conquered the Oshu Fuji-

wara. The position of Oshu general commissioner

was founded to manage affairs in this region for the

shogunate.

shugo (military governors) The shugo rank was

established by Minamoto no Yoritomo to maintain

control over the provinces. The position became a

formal part of the administrative structure of the

Kamakura shogunate. Although Yoritomo hand-

selected the first shugo, this title became hereditary

over time. Duties of this office included general

police and peacekeeping activities and administra-

tive responsibilities such as investigating crimes and

judging legal cases.

jito (land stewards) Land stewards, or jito, were

officials appointed by the Kamakura shogunate from

among its most trusted vassals to serve as estate

(shoen) supervisors. Jito were responsible for over-

seeing the shogunate’s tax interests on these private

estates. As such, jito handled the collection of taxes

and ensured correct distribution. The jito system,

however, was also a means whereby the Kamakura

shogunate could reward its loyal vassals (gokenin) for

their service to the military government. Over time,

jito became an inherited office.

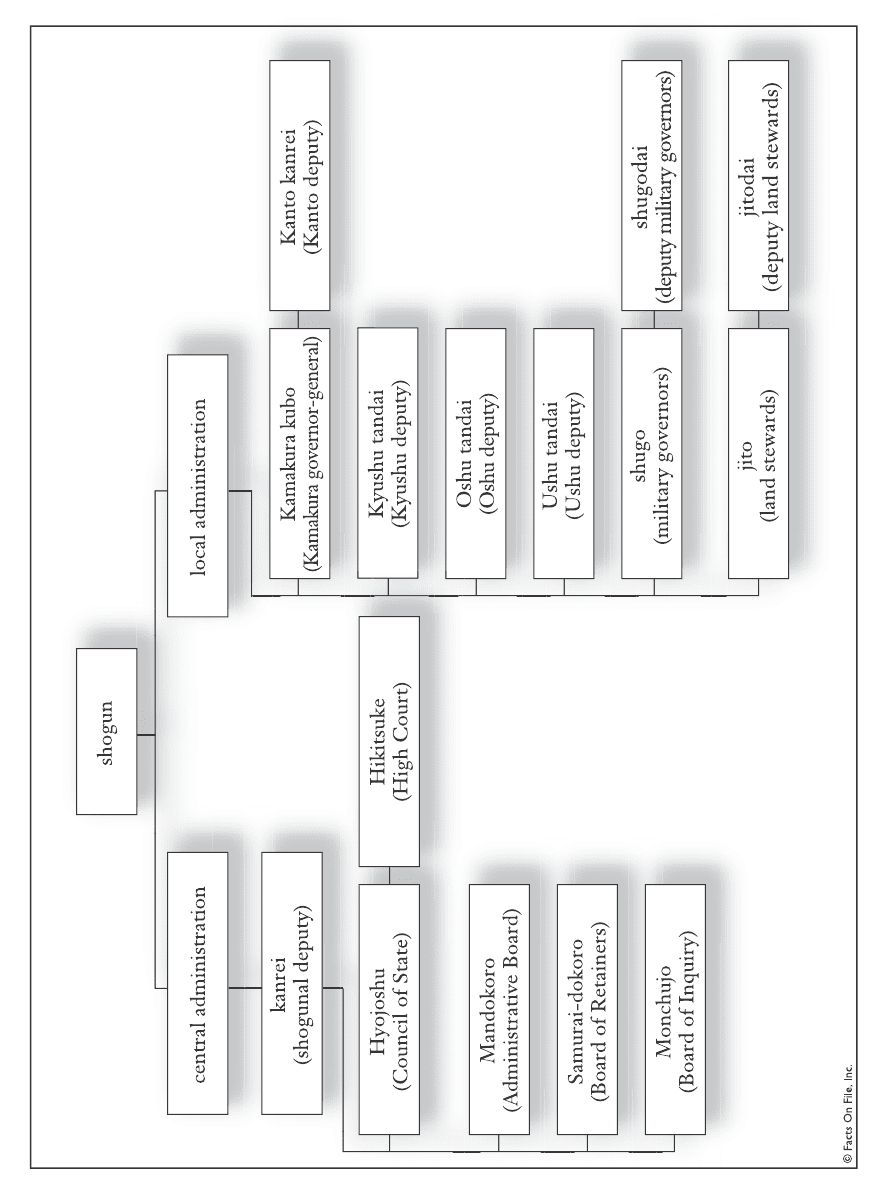

Muromachi Shogunate

The Ashikaga shogunate inherited much of the ad-

ministrative structure of the Kamakura government.

Key offices such as the Mandokoro (Administrative

Board), Samurai-dokoro (Board of Retainers), and

the Monchujo (Board of Inquiry) remained. The fol-

lowing description of individual positions and offices

only covers those not already dealt with in the sec-

tion on the Kamakura administrative structure. The

only exception is when a particular office or position

underwent significant change in the Muromachi

period.

kanrei (shogunal deputy) The office of kanrei was

instituted by the Ashikaga shogunate. The role of the

shogunal deputy was to assist the shogun in adminis-

tering the warrior government. One important

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

94

responsibility of the kanrei was to oversee relations

between the shogunate and the shugo (military gover-

nors). Military governors had grown more powerful

by this time and posed a threat to the governing

authority of the shogunate. Three warrior families—

the Shiba, the Hosokawa, and the Hatakeyama—

shared this position on a rotating basis.

Hyojoshu (Council of State) See above under

“Kamakura Shogunate.”

Hikitsuke (High Court) See above under “Kama-

kura Shogunate.”

Mandokoro (Administrative Board) See above

under “Kamakura Shogunate.”

Samurai-dokoro (Board of Retainers) See above

under “Kamakura Shogunate.”

Monchujo (Board of Inquiry) See above under

“Kamakura Shogunate.” In the Muromachi period,

many of the responsibilities formerly carried out by

the Monchujo were reassigned to the Mandokoro

(Administrative Board), and the Board of Inquiry

was reduced to record keeping.

Kamakura kubo (Kamakura governor-general)

During the Muromachi period, the term kubo

referred both to Ashikaga shoguns and to their gov-

ernors-general. The post of Kamakura kubo was

established in 1336 to monitor the interests of the

shogunate in Kamakura and eastern Japan. To this

end, the Kamakura kubo was responsible for govern-

ing affairs in this region. The Kamakura governor-

general became a hereditary position within the

Ashikaga family.

Kanto kanrei (Kanto deputy) The Kanto kanrei

was a position initiated by the Ashikaga shogunate

in 1349. Headquartered in Kyoto, the shogunate

needed an overseer in the Kanto region, which

included Kamakura. The Kanto deputy fulfilled this

role, especially in providing assistance to Kanto area

governors-general (Kamakura kubo). From the latter

half of the 14th century, members of different

branches of the Uesugi family held the position of

Kanto kanrei.

Kyushu tandai (Kyushu deputy)

Oshu tandai (Oshu deputy)

Ushu tandai (Ushu deputy) As part of the Ashik-

aga shogunates’ effort to maintain control over polit-

ical and military affairs, regional deputies (tandai)

were appointed in parts of Japan that were deemed

strategically important. The Muromachi-period gov-

ernment placed deputies in northwestern Honshu

(the Oshu and Ushu tandai) and in Kyushu (Kyushu

tandai). See also “Rokuhara tandai” and “Chinzei

tandai” above under “Kamakura Shogunate.”

shugo (military governors) See above under “Ka-

makura Shogunate.”

shugodai (deputy military governors) The posi-

tion of shugodai existed during the Kamakura period.

Up until the Mongol invasions in the latter half of

the 13th century, shugo infrequently lived in the

provinces they were assigned to govern. This

responsibility fell to the shugodai. In the Muromachi

period, the shugodai became a more formal part of

the shogunate’s administrative structure.

jito (land stewards) See above under “Kamakura

Shogunate.”

jitodai (deputy land stewards) Within the jito sys-

tem, some shogunal vassals received appointments

to oversee multiple estates. When this occurred,

deputy land stewards were used to govern these

additional regions. This position was significant

enough to become a formal part of the Ashikaga

shogunate’s administrative structure.

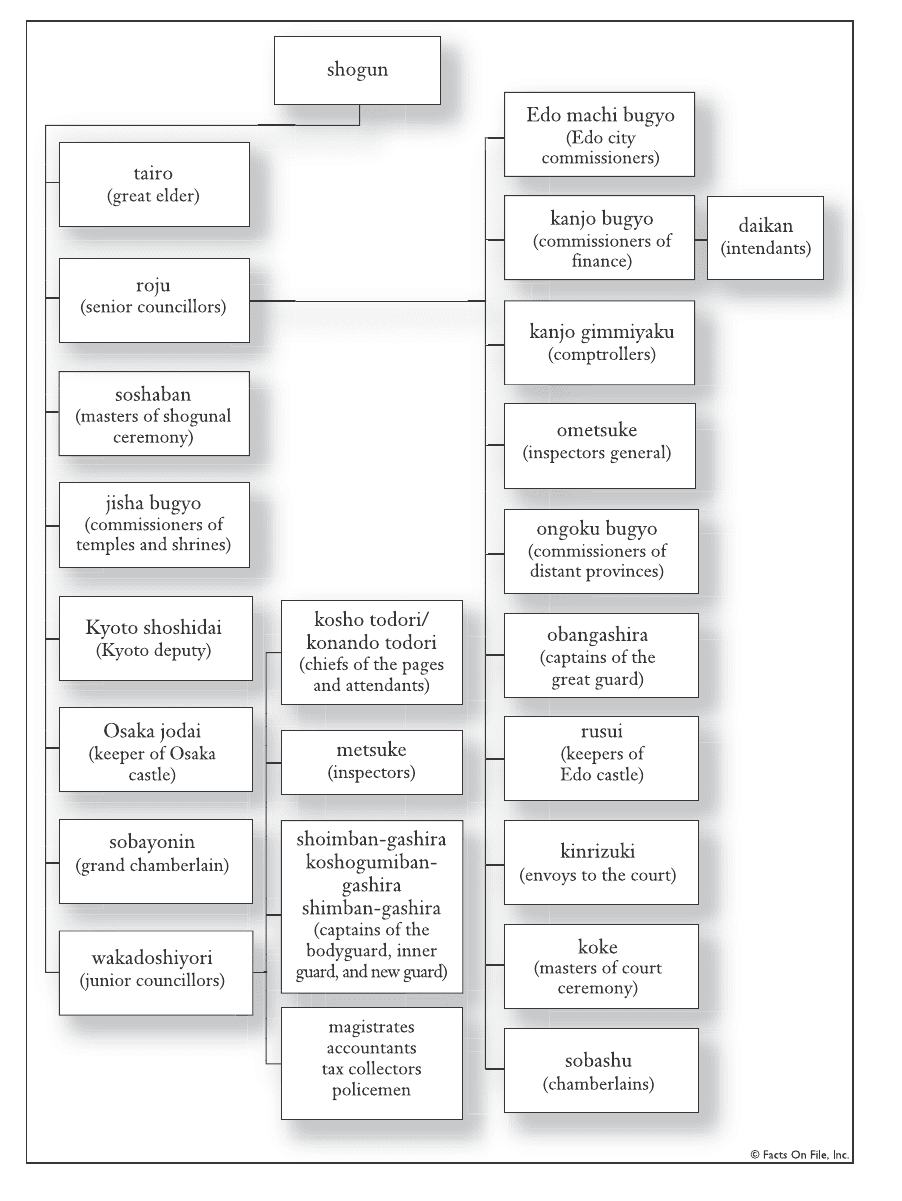

Tokugawa Shogunate

tairo (great elder) Although the position of tairo

ranked just below shogun in the Edo period’s admin-

istrative structure, it was in fact an office rarely

filled. When it was assigned, it was often used as a

sinecure. One important exception to this pattern

was Ii Naosuke (1815–60), who used this position to

run the shogunate.

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

96

roju (senior councillors) Roju were senior officials

of the Tokugawa shogunate who watched over the

entire government structure and the functioning of

its many offices. In short, they administered the

affairs of state, both domestic and foreign, for the

shogunate. Senior councillors—usually four or five

in number—were appointed from among the fudai

(hereditary vassals) daimyo.

Edo machi bugyo (Edo city commissioners) Edo

machi bugyo were shogunal officials charged with

overseeing matters of city life concerning the chonin

(townspeople and merchants). Edo city commission-

ers were selected from among those of hatamoto

(“bannerman”: direct samurai retainers of the

shogunate) rank.

kanjo bugyo (commissioners of finance) Com-

missioners of finance served the shogunate as offi-

cials accountable for financial matters. Kanjo bugyo

reported directly to the senior councillors (roju).

These commissioners—usually only four in number

but overseeing a large number of assistants—were

appointed from those of hatamoto rank.

daikan (intendants) Although the office of daikan

existed prior to the Edo period, it became a formal

part of the Tokugawa shogunate’s administrative

structure. These local government officials super-

vised and managed the shogunate’s personal land-

holdings (tenryo).

kanjo gimmiyaku (comptrollers) This office, cre-

ated in 1682, was charged with investigating, and

otherwise overseeing, the operations of the kanjo

bugyo (commissioners of finance). Although comp-

trollers were structurally lower than the commis-

sioners of finance, they functioned as a control over

the higher office’s activities. Kanjo gimmiyaku re-

ported to the senior councillors (roju).

ometsuke (inspectors general) This office origi-

nated in 1632 when the third shogun, Tokugawa

Iemitsu, appointed four people of hatamoto (banner-

man) rank to oversee activities and places of poten-

tial trouble to the shogunate. Those who served as

ometsuke were often senior officials with extensive

government service. Among the areas of concern

scrutinized by the ometsuke were the road system,

daimyo activities, and groups troublesome to the

shogunate such as Christian missionaries and their

Japanese followers. Inspectors general reported to

the senior councillors (roju).

ongoku bugyo (commissioners of distant pro-

vinces) The post of ongoku bugyo was similar in duty

to the Edo machi bugyo (Edo city commissioners; see

above) except that these commissioners served in

localities other than Edo, including Kyoto and

Osaka. Like the Edo machi bugyo, they were selected

from among families of hatamoto (bannerman) rank.

See above under “Edo machi bugyo.”

obangashira (captains of the great guard) Cap-

tains of the Great Guard were responsible for secu-

rity at the three castles—at Edo, Kyoto, and

Osaka—associated with the shogunate

rusui (keepers of Edo Castle) The rusui primar-

ily supervised and when necessary, defended Edo

Castle. Their post was analogous to that of jodai

(castellan).

kinrizuki (envoys to the court) The kinrizuki

served as imperial palace inspectors.

koke (masters of court ceremony) Literally,

“elevated families,” koke were hereditary govern-

ment officials responsible for carrying out official

ceremonies and rituals for the shogunate. In addi-

tion, masters of court ceremony were used as shogu-

nal representatives at court, temple, and shrine

functions.

sobashu (chamberlains) The office of sobashu was

established in 1653 by the fourth shogun, Toku-

gawa Ietsuna. Chamberlains were in direct service

to the shoguns and, bureaucratically, reported to

the roju.

soshaban (masters of shogunal ceremony) Mas-

ters of shogunal ceremony were protocol officials

who reported directly to the shogun. The 20-some

soshaban were responsible for such tasks as keeping

the shogun’s schedule and organizing shogunal cere-

monies.

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

98

jisha bugyo (commissioners of temples and

shrines) Temple and shrine commissioners, usu-

ally four in number, supervised temple and shrine

affairs, including matters involving religious hierar-

chies and the landholdings of these institutions.

Among other responsibilities, they also held sub-

sidiary duties involving legal matters in regions out-

side of the Edo area.

Kyoto shoshidai (Kyoto deputy) The post of

Kyoto deputy was first established by Oda

Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi, during the

Azuchi-Momoyama period, to oversee the affairs of

Kyoto, especially the activities of the imperial court

and nearby territories. This office became formal-

ized within the administrative structure of the Toku-

gawa shogunate.

Osaka jodai (keeper of Osaka Castle) The Osaka

jodai, or keeper of Osaka Castle, was the senior mili-

tary officer in central Japan. As the primary adminis-

trator in the region, the Osaka jodai maintained the

military strength of Osaka Castle. During the Edo

period, jodai, including the Osaka jodai, served as the

proxy of the Tokugawa shogun in commanding the

respective castle. This rank was reserved for middle-

ranking daimyo, and holders of this rank were fre-

quently promoted to posts of Kyoto deputy (Kyoto

shoshidai) and senior councillor (roju).

sobayonin (grand chamberlain) The grand cham-

berlain was responsible for transmitting messages

between the Tokugawa shogun and the roju, the

shogun’s senior councillors. This position was cre-

ated in 1681.

G OVERNMENT

99

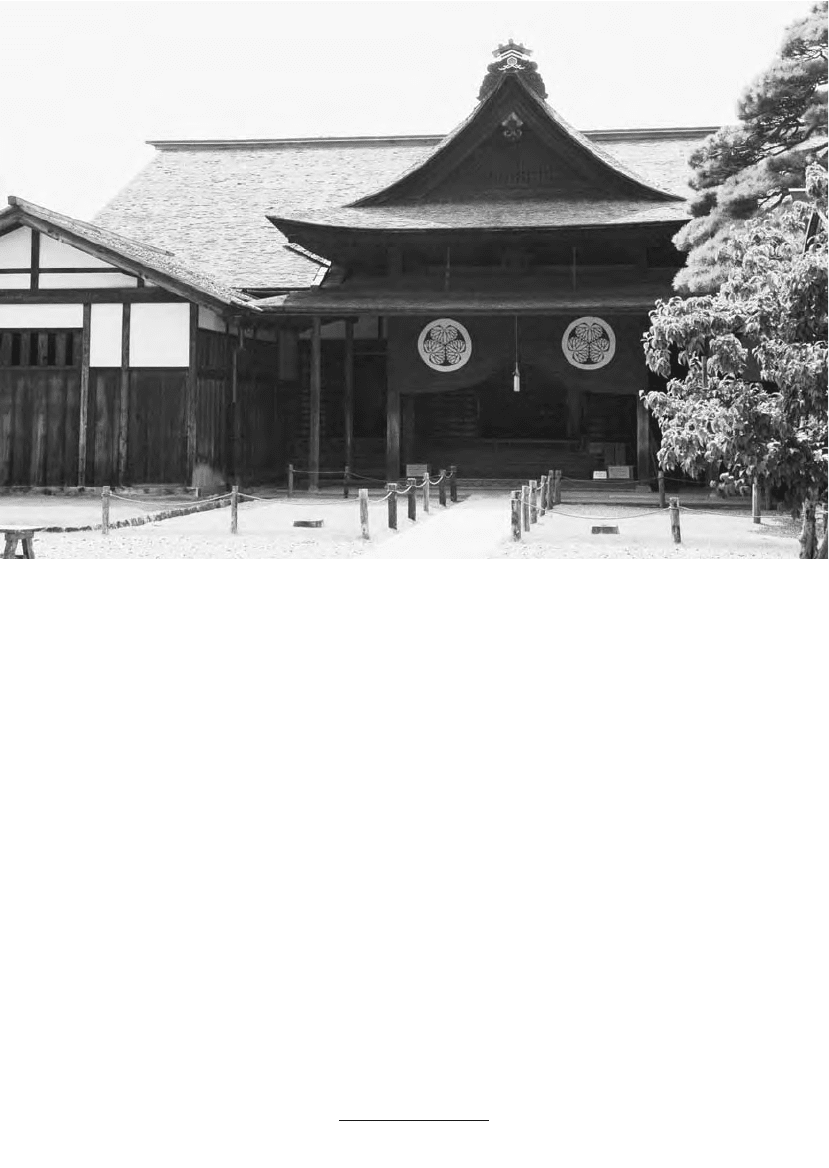

3.1 Example of an Edo-period local government building (jinya) (Photo William E. Deal)

wakadoshiyori (junior councillors) Junior coun-

cillors, or “young elders” assisted the roju and sur-

veyed the hatamoto and gokenin. Additionally, they

supervised artisans, artists, physicians, palace guards,

and construction work. In case of a war, the waka-

doshiyori led the hatamoto into battle. The position

was created in 1633 and chosen from the fudai

daimyo.

kosho todori/konando todori (chiefs of the pages

and attendants) Kosho todori/konando todori served as

the chiefs of shogunal pages and attendants.

metsuke (inspectors) Metsuke performed police

and enforcement duties at numerous levels. Not

only did they serve as high-level spies for their mili-

tary rulers, but they also evaluated other shogunal

officials and staff as well.

shoimban-gashira (captains of the bodyguard),

koshogumiban-gashira (captains of the inner

guard), shimban-gashira (captains of the new

guard) The various bodyguards operated under the

command of the junior councillors during war.

List of Shoguns and Regents

KAMAKURA SHOGUNS

Shogun Birth/ Held

Death Office

1. Minamoto 1147–1199 1192–1199

Yoritomo

2. Minamoto 1182–1204 1202–1203

Yoriie

3. Minamoto 1192–1219 1203–1219

Sanetomo

4. Fujiwara 1218–1256 1226–1244

(Kujo)

Yoritsune

5. Fujiwara 1239–1256 1244–1252

(Kujo)

Yoritsugu

6. Prince 1242–1274 1252–1266

Munetaka

7. Prince 1264–1326 1266–1289

Koreyasu

8. Prince 1276–1328 1289–1308

Hisaakira

9. Prince 1301–1333 1308–1333

Morikuni

HOJO SHOGUNAL REGENTS

(SHIKKEN)

Regent Birth/ Held

Death Office

1. Hojo Tokimasa 1138–1215 1203–1205

2. Hojo Yoshitoki 1163–1224 1205–1224

3. Hojo Yasutoki 1183–1242 1224–1242

4. Hojo Tsunetoki 1224–1246 1242–1246

5. Hojo Tokiyori 1227–1263 1246–1256

6. Hojo Nagatoki 1229–1264 1256–1264

7. Hojo Masamura 1205–1273 1264–1268

8. Hojo Tokimune 1251–1284 1268–1284

9. Hojo Sadatoki 1271–1311 1284–1301

10. Hojo Morotoki 1275–1311 1301–1311

11. Hojo Munenobu d. 1312 1311–1312

12. Hojo Hirotoki 1233–1315 1312–1315

13. Hojo Mototoki d. 1333 1315–1316

14. Hojo Takatoki 1303–1333 1316–1326

15. Hojo Sadaakira d. 1333 1326

16. Hojo Moritoki 1295–1333 1326–1333

MUROMACHI SHOGUNS

Shogun Birth/ Held

Death Office

1. Ashikaga Takauji 1305–1358 1338–1358

2. Ashikaga Yoshiakira 1330–1367 1358–1367

3. Ashikaga Yoshimitsu 1358–1408 1368–1394

4. Ashikaga Yoshimochi 1386–1428 1394–1423

5. Ashikaga Yoshikazu 1407–1425 1423–1425

6. Ashikaga Yoshinori 1394–1441 1429–1441

7. Ashikaga Yoshikatsu 1434–1443 1442–1443

8. Ashikaga Yoshimasa 1436–1490 1449–1473

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

100

9. Ashikaga Yoshihisa 1465–1489 1473–1489

10. Ashikaga Yoshitane 1466–1523 1490–1493

and

1508–1521

11. Ashikaga Yoshizumi 1480–1511 1494–1508

12. Ashikaga Yoshiharu 1511–1550 1521–1546

13. Ashikaga Yoshiteru 1536–1565 1546–1565

14. Ashikaga Yoshihide 1538–1568 1568

15. Ashikaga Yoshiaki 1537–1597 1568–1573

EDO SHOGUNS

Shogun Birth/ Held

Death Office

1. Tokugawa Ieyasu 1542–1616 1603–1605

2. Tokugawa Hidetada 1570–1623 1605–1623

3. Tokugawa Iemitsu 1604–1651 1623–1651

4. Tokugawa Ietsuna 1641–1680 1651–1680

5. Tokugawa Tsunayoshi 1646–1709 1680–1709

6. Tokugawa Ienobu 1633–1712 1709–1712

7. Tokugawa Ietsugu 1709–1716 1713–1716

8. Tokugawa Yoshimune 1684–1751 1716–1745

9. Tokugawa Ieshige 1711–1761 1745–1760

10. Tokugawa Ieharu 1737–1786 1760–1786

11. Tokugawa Ienari 1772–1841 1787–1837

12. Tokugawa Ieyoshi 1793–1853 1837–1853

13. Tokugawa Iesada 1824–1858 1853–1858

14. Tokugawa Iemochi 1846–1866 1858–1866

15. Tokugawa Yoshinobu 1837–1913 1866–1867

LAW, CRIME, AND

PUNISHMENT

Pre-Kamakura Shogunate

Prior to the establishment of the Kamakura shogu-

nate, Japan’s legal system existed mostly to define

positions and behaviors within the court aristocracy

(kugeho). As far as the common person was con-

cerned, regulations were both loosely defined and

enforced by local landowners, and these laws were

largely pieced together from a combination of reli-

gious codes and regulations adopted from the Chi-

nese system. Hardly a comprehensive national legal

system, the pre-Kamakura legal codes were devel-

oped locally by estate owners for those working the

land, military commanders for the soldiers under

them, religious leaders for lesser clergy, and high-

ranking domain officials for their deputies. The

penalties for violating these codes were also micro-

managed and set by the whim of the superior. They

included both corporal and capital forms of punish-

ment, and were informed by Confucian ideals aimed

not only to punish, but also to change the criminal’s

heart leading to personal betterment even if, as in

the case of a death sentence, that betterment meant

improvement in the next life.

Kamakura Shogunate

With the rise of the warrior class and the unification

of Japan under the Kamakura shogunate, the Japan-

ese legal system acquired the form of the traditional

samurai code of ethics focused on maintenance of the

hierarchy and familial honor and obligation. Thus

most of the early laws set forth by the shogunate were

aimed at solidifying the power of the ruling class by

delineating the privileges of the samurai warlords and

the obligations of their vassals. This warrior-class law,

known as bukeho, was quickly disseminated through-

out the land. By the start of the Muromachi shogu-

nate, most of the values and obligations of the

samurai had been internalized by the populace.

The first official codification of the warrior-class

laws, called the Joei Shikimoku, was issued in 1232

by the Kamakura shogunate, and it would set the

tone for all the edicts issued by the military govern-

ment for essentially the next 700 years. This code

served to clearly define the roles of samurai lords and

their vassals and was based on a combination of many

of the local legal codes that antedated the shogunate.

Thus, it was the first centralized national legal code

compiled from all of the minor regulations that had

been in existence on local estates, in military regi-

G OVERNMENT

101

mens, in monasteries, and in regional government

offices. The last, and most important, function of this

new law code was to clarify the now limited authority

of the imperial court at Kyoto from which the war-

rior class had assumed power.

Muromachi Shogunate

This first legal code remained relatively unchanged

throughout the Kamakura reign with only a few

amendments made in the form of supplementary

edicts called tsuika. It was the primary national legal

code of this period. After assuming power from the

Kamakura government, the Ashikaga family of

Muromachi shoguns continued to support legisla-

tion delineated in the Joei Shikimoku, considering

their own edicts to be merely supplemental to the

primacy of the original code. With the consultation

of a board of scholars and advisers, Ashikaga Takauji

included the major addition made by the Muro-

machi in 1336. This supplemental edict, the Kemmu

Shikimoku, was based on a seventh-century consti-

tution written by Prince Shotoku and consisted of

17 articles dealing with the attitudes and behaviors

expected of the warrior class. These items dealt with

issues ranging from personal habits to the attention

a ruler should pay the courtiers and peasants.

Another major contribution of the Muromachi

period to the legal structure of Japan was the devel-

opment of principles of group responsibility known

as renza and enza. In accordance with these values,

blame was not simply assigned to the guilty individ-

ual when a crime was committed, but it was also

assigned to that individual’s family and perhaps the

larger community of which he was a part. Members

of those groups associated with the criminal would

often be subject to as severe a penalty as the one who

had committed the crime. Accordingly communities

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

102

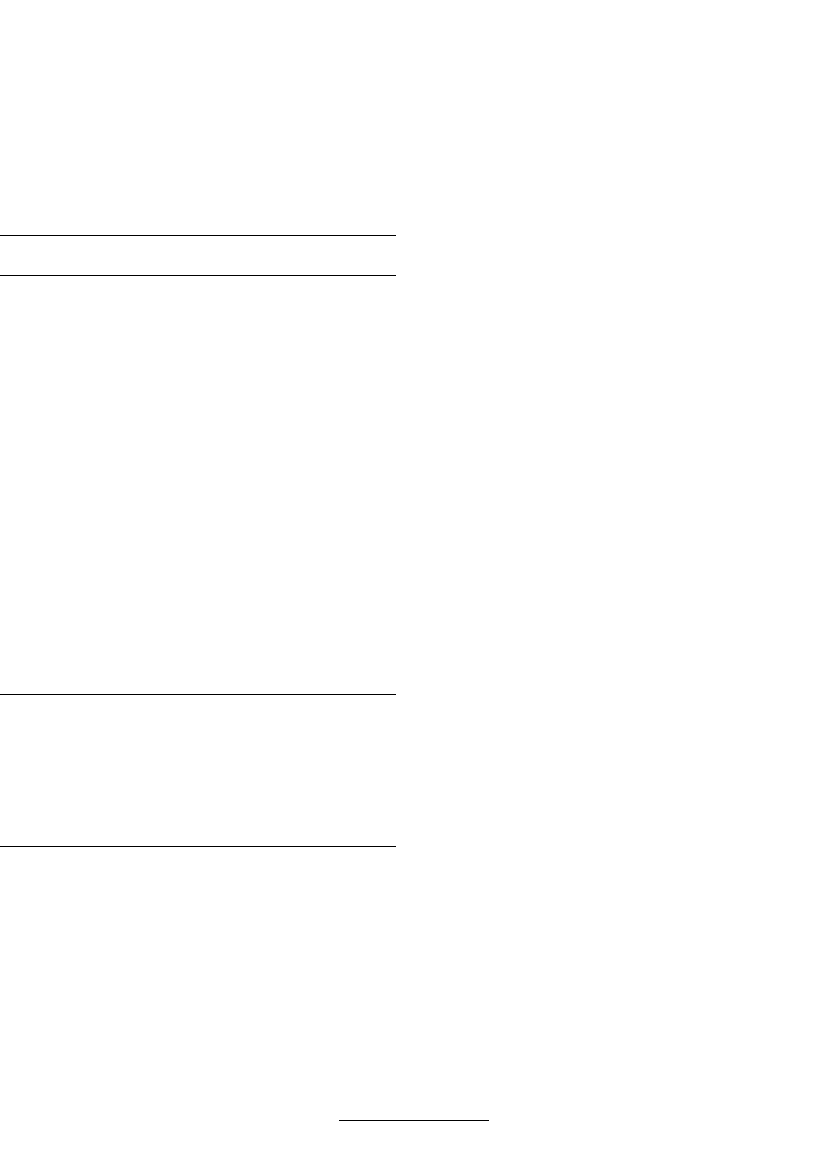

3.2 Example of an uchikomi, a device used to apprehend a criminal or criminal suspect (Illustration Grace Vibbert)

were encouraged to restrain rebellious individuals

before they aroused the attention of the government

authorities. Legal disputes were discouraged with

the promotion of the kenka ryoseibai policy, which

stated that the factions on either side of any argu-

ment were to be held equally accountable for the

disagreement. Thus, if a fight over land rights arose

between two neighboring lords and they could not

reach an agreement themselves, the state would con-

fiscate both of their lands.

As the 15th century began, disputes over shogu-

nal succession leading to the Onin War caused a

destabilization within the Muromachi government

resulting in a decentralization of power starting as

early as the 1460s. As the governmental structure

fell into disarray, the legal system again became frag-

mented as local daimyo rose to power, enacting indi-

vidual laws for their personal domains. These

domainal codes, known as bunkokuho, were still

largely based upon the once universal laws set forth

by the Kamakura and Muromachi shoguns with

some additions made that were taken from the tradi-

tions of the individual daimyo family. These codes

strictly defined the role of vassals, and the power of

the lords to control the activities of those living and

working on their lands. Regulations were also set

forth that stringently prohibited the cultivation of

lands by commoners without the approval of the

lord, and travel into or out of the domain was also

heavily restricted.

Azuchi-Momoyama Period

The regional laws set forth by the increasingly pow-

erful daimyo continued to make up the primary

form of legal structure after the Muromachi shogu-

nate officially collapsed and the Azuchi-Momoyama

period began. However, Japan as a nation was very

unstable during this period, and domains changed

hands often, making it hard to enforce any one legal

code for very long. Thus, land rights were often

abused and much criminal activity went unpunished.

Still, honor was very important to even the most

unruly samurai, and, at least among the warrior

class, infractions of the traditional bushi code of

ethics were dealt with swiftly within bands of samu-

rai in the course of fighting the many skirmishes that

broke out between competing daimyo.

This long period of chaos that consumed much

of the 15th and 16th centuries in Japan came to a

close when Tokugawa Ieyasu united the country in

the early 17th century, reestablishing shogunal rule

and ushering in one of the longest periods of

national stability. With the newly centralized gov-

ernment came a new national code of laws, which

quickly became more structured and sophisticated as

Japanese society moved into a time of peace and

prosperity. The Edo period brought many changes

in class structure especially for the warrior class as

they put down their swords and armor and assumed

the bureaucratic duties of the peacetime ruler, and

the laws set forth by the Tokugawa shoguns were

aimed at clearly defining class groups and further

empowering the ruling ranks.

G OVERNMENT

103

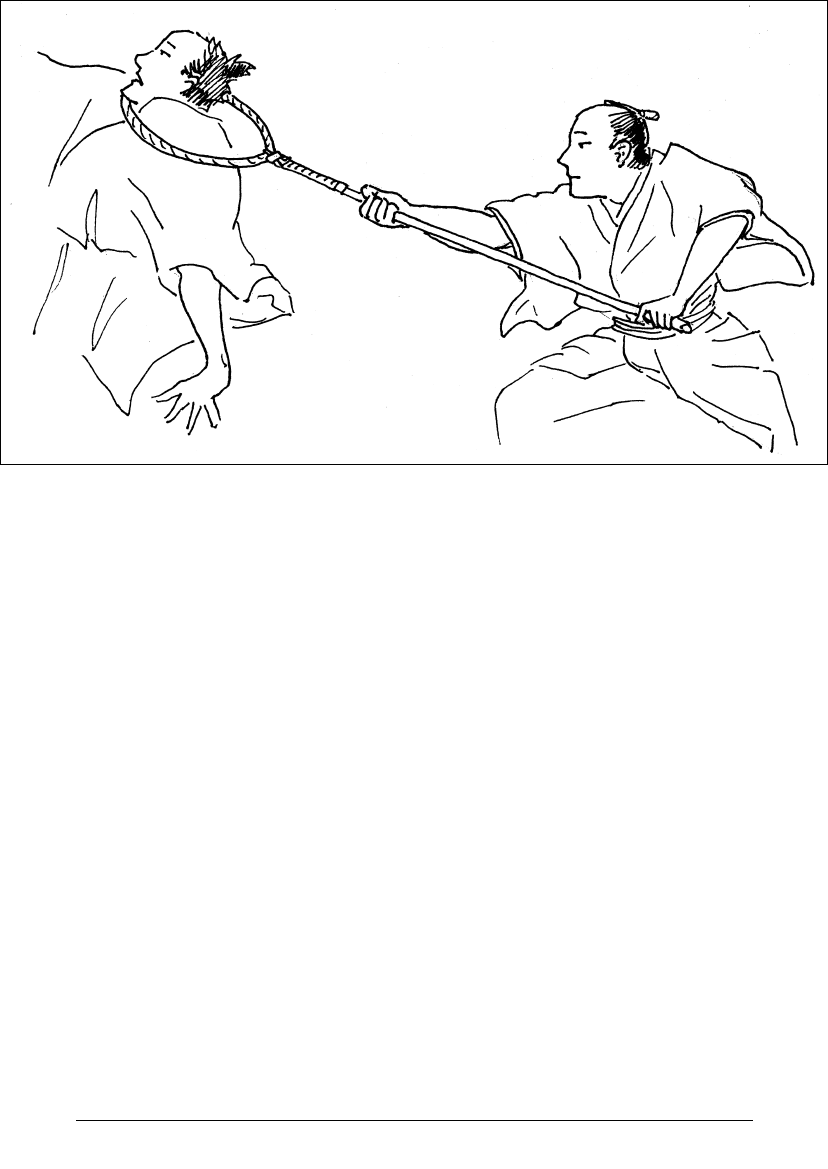

3.3 Example of shujinkago, a bamboo basket used to

transport criminals during the Edo period

(Photo

William E. Deal)