Deal W.E. Handbook To Life In Medieval And Early Modern Japan

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

have an adjoining space used for the family’s busi-

ness, whether a shop or a small factory.

READING

Art

Addiss 1996: introduction to visual aspects of

medieval and early modern art; Mason 2005: histor-

ical survey including medieval and early modern art;

Munsterberg 1974, 344–369: historical survey of

medieval and early modern art; Murase 1986:

medieval and early modern scrolls and prints; Noma

1966: historical survey including medieval and early

modern art; Sadao and Wada 2003: historical survey

including medieval and early modern art; Stanley-

Baker 1984: historical survey including medieval and

early modern art; Wilson 1995: ceramic materials

and techniques; Yamasaki (ed.) 1981: chronology of

art history; Yoshiaki and Rosenfield 1984: medieval

and early modern calligraphy; Lane 1978: ukiyo-e;

Guth 1996: Edo-period art; Akiyama 1961: medieval

and early modern painting; Shimizu (ed.) 1988:

medieval and early modern art; Grilli 1970: screen

paintings; ten Grotenhuis 1998: mandala paintings;

Cort 1992: Seto and Mino ceramics; Impey 1996:

early modern porcelain

Tea and Related Arts

Pitelka (ed.) 2003: tea art, culture, and practice;

Anderson 1991: tea ritual; Hayashiya 1979: tea cere-

mony; Tanaka and Tanaka 1998: tea ceremony; Var-

ley and Kumakura 1989: tea history; Fujioka 1973:

tea ceremony utensils; Hayashiya, Nakamura, and

Hayashiya 1974: tea ceremony and the arts

Architecture

Coaldrake 1996: selected religious and secular archi-

tecture with emphasis on the early modern period;

Kuitert 2002: history of medieval and early modern

gardens; Nishi and Hozumi 1985: medieval and

early modern religious and secular architecture;

Inaba and Nakayama 2000: medieval and early mod-

ern domestic architecture; Hashimoto 1981: Shoin-

style architecture; Hinago 1986: castles; Hirai 1973:

medieval architecture.

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

324

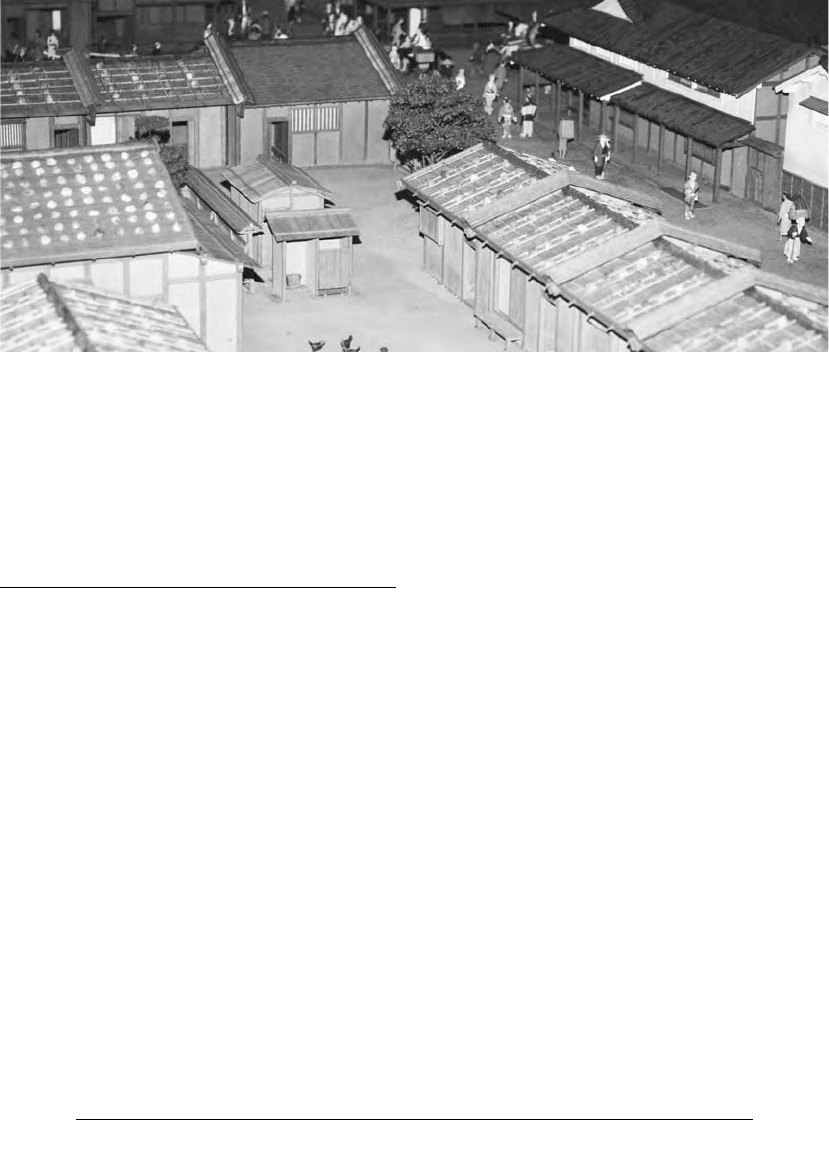

10.12 Model of commoner residences (machiya) in Edo (Edo-Tokyo Museum exhibit; Photo William E. Deal)

TRAVEL AND

COMMUNICATION

11

INTRODUCTION

Unlike the contemporary world in which one can

communicate with others by telephone, the internet,

e-mail, and other means requiring no physical

movement from one place to another, in medieval

and early modern Japan, communication across dis-

tances required travel. The topography of the land

had a significant impact on the difficulty of long-dis-

tance travel and communication. Oceans separated

Japan from other countries, and mountains and

plains separated different regions within the Japan-

ese islands. Thus, travel and communication were

closely connected matters in Japan during this time

period. Further, the development of commercial

markets required dependable transportation net-

works so that travel and communication always had

economic implications. Specific economic issues are

discussed in chapter 4: Society and Economy.

There were a number of different social, eco-

nomic, religious, and political developments that

strongly influenced the development of possibilities

for travel and communication in the medieval and

early modern periods. Not surprisingly, shogunal

officials were concerned with controlling and regu-

lating travel. The government sought control over

the distribution of commercial products, the move-

ment of people, and the spread of ideas that might

challenge government authority.

Another aspect of travel in the medieval and early

modern periods was related to religious pilgrimage.

Particularly popular was travel to Japanese sacred

sites, such as the Ise and Izumo Shrines, the Shikoku

88-temple pilgrimage connected to the Shingon

Buddhist school founder, Kukai, and the 33 pilgrim-

age temples dedicated to the worship of the bod-

hisattva Kannon. While pilgrimage was a feature of

medieval Japanese religious life, it was not until the

relative stability of the Edo period that religious

travel became widespread among all social and eco-

nomic classes. Besides a system of roads to carry pil-

grims on their journeys, other infrastructure

developed to service the needs of pilgrims, including

inns for food and lodging, and shops where both

religious and other goods could be purchased. The

lines between pilgrimage and tourism began to blur

in the Edo period. Religious aspects of pilgrimage

are treated in chapter 6: Religion, but pilgrimage is

discussed in this chapter because of its impact on

travel and communication, especially in the early

modern period.

Significant to the development of transportation

and communication systems in the Edo period was

the practice of alternate-year attendance (sankin

kotai) established in the 1630s. This system required

daimyo to set up residences at Edo and to appear

before the shogun every other year. Though this

served ostensibly ceremonial purposes, there was

also a strategic feature: daimyo families, that is

daimyo wives and children, were forced to live per-

manently in Edo as—effectively—hostages. The

daimyo traveled to Edo every other year but their

families were made to remain in Edo. This was one

way for the shogunate to induce obeisance from the

daimyo, especially those that might have ideas of

asserting their power and influence against shogunal

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

326

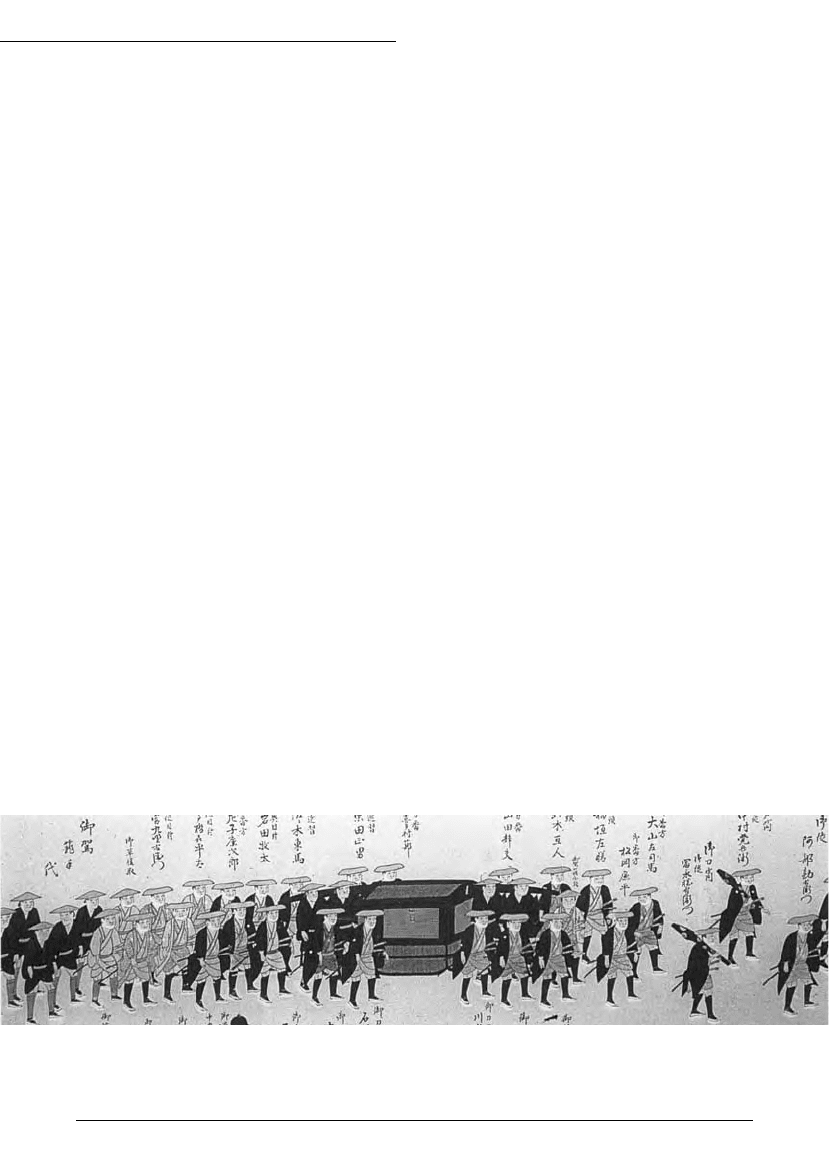

11.1 Procession of a domain lord (Edo-Tokyo Museum exhibit; Photo William E. Deal)

interests. This system held rival daimyo in check

because of the great expense of maintaining two sep-

arate administrative locations (both in their own

domain and a residence at the capital) and because of

the great expense required to travel to Edo every

other year.

It is estimated that a daimyo spent as much as 80

percent of his income traveling to Edo and main-

taining two residences. Part of the traveling expense

was the result of the large retinue of vassals, ser-

vants, and others who traveled with the daimyo back

and forth from Edo. Daimyo and their supporting

legions were required to use the main roads because

these roads were under direct control of the shogu-

nate. Daimyo processions to and from the capital

could sometimes exceed 300 persons, though the

size was a reflection of daimyo wealth and power.

The sankin kotai system produced a number of

direct effects on modes of early modern travel and

communication. It resulted in the systematization of

highways needed to convey people to and from the

capital. In turn, this improved communication

between different regions of Japan. It also helped to

establish an infrastructure needed to ease the move-

ment of people across the road network. Thus, facil-

ities for travelers were established, including inns,

shops, and other services supplying the needs of

travelers.

Commercial traffic was always a catalyst for the

development of roads throughout Japan’s medieval

and early modern periods. As early as the late sev-

enth century, roads were constructed so that rice

could be delivered to the capital. It was not until the

Edo period that the movement of large amounts of

commercial goods became commonplace in Japan.

Thus, the increased commerce of this time required

more and better roads, and, at the same time, the

improved road system helped the economy to grow.

The road system aided in the growth of Edo and

Osaka as urban centers because markets and com-

merce became much more widespread with

improved travel and communication. Of further

importance for the increase of trade was the use of

coastal water routes to ship goods around Japan.

Although international trade was severely limited in

the Edo period by the Tokugawa shogunate’s

national seclusion policy, some trade was carried on

with the Chinese and the Dutch.

LAND TRAVEL AND

COMMUNICATION

Modes of Land Travel and

Communication

Travel throughout the medieval and early modern

periods was conducted almost entirely on foot. The

wealthy might be carried in palanquins, and goods

and communications were sometimes conveyed by

horse, but the chief mode of transport—and hence

communication—was on foot.

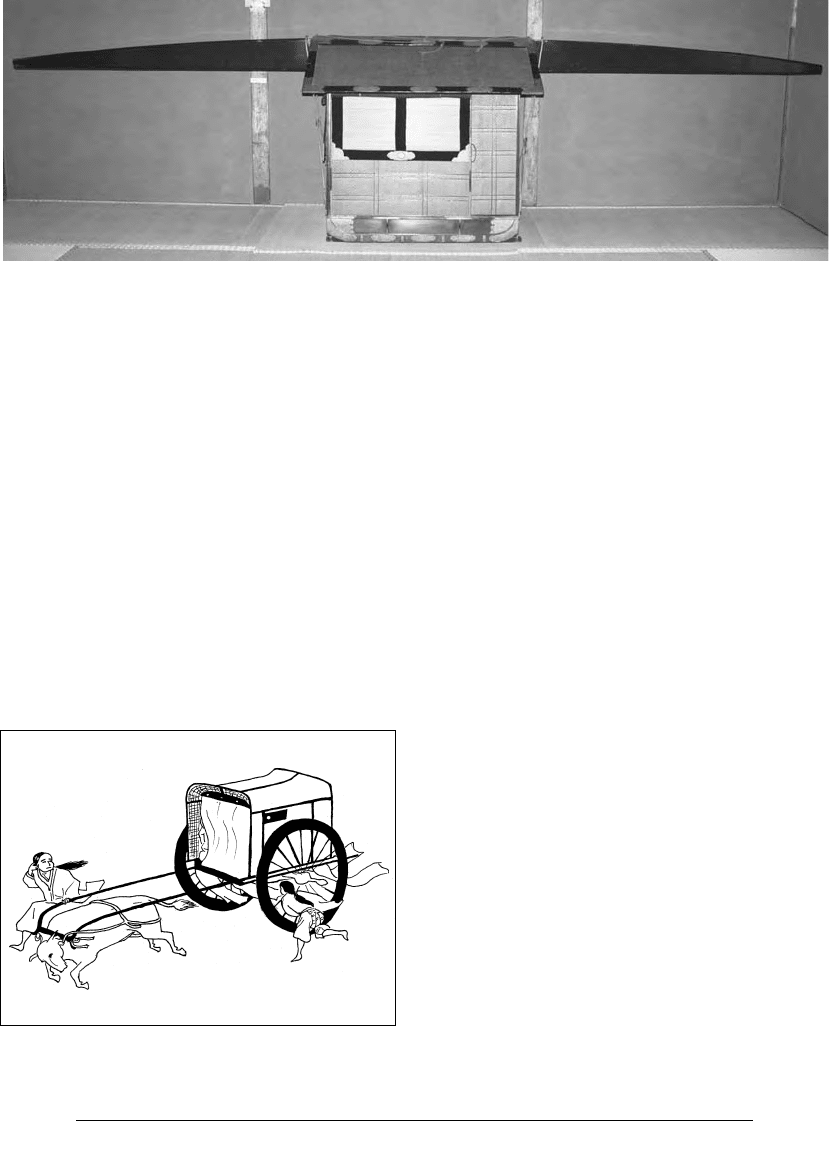

PALANQUIN

For those who were wealthy—such as aristocrats,

lords, and important clergy—the palanquin (kago)

was the preferred mode of travel. The palanquin is

an enclosed portable seat, constructed of wood or

bamboo, mounted on two long poles that extend

beyond the front and back of the seat. The wood of

fancy palanquins might be lacquered. It was carried

on the shoulders of two men. Generally, a palanquin

was used to convey one person. First used in the

medieval period, the use of palanquins became wide-

spread in the early modern period with the increased

road traffic. As it did with so many symbols of

power, the Tokugawa shogunate strictly controlled

the use of palanquins based on social class.

PACKHORSEMEN

As commerce increased in the early modern period,

the need for more efficient ways to transport people

and goods along the roads became more important.

The occupation known as packhorseman (bashaku)

developed. Packhorsemen used packhorses to trans-

port people and commodities along the road system.

In the Kamakura period, packhorsemen were used

by village communities to transport their goods to

town markets. In the latter part of the medieval

period, packhorsemen held a great deal of control

over land transportation, and they sometimes

protested over conditions they viewed as unfavor-

T RAVEL AND C OMMUNICATION

327

able for their business, such as toll barriers estab-

lished by the government to regulate the movement

of people and goods. By the early modern period,

their services were in great demand. Like other

tradespeople, they organized themselves into guilds.

Some packhorsemen became wholesale merchants,

obtaining significant wealth in the process.

COURIERS

One way in which communications were expedited

in the medieval and early modern periods was by the

use of running couriers known as hikyaku (“flying

feet”). Although the use of couriers dates back to the

early medieval period, their utilization did not

become prevalent until the early modern period. In

the Edo period, couriers were used in a number of

ways by different social classes. They were utilized

by the shogunate in the conduct of government

business. Domain lords used couriers to maintain

communications between their domain and Edo res-

idences. Merchants—especially those in Edo, Osaka,

and Kyoto—relied on couriers for the conduct of

business between cities. A postal system developed

using couriers to deliver correspondence between

cities. It took six days for a courier to deliver a letter

from Edo to Osaka.

Early Modern Road System

Road systems date back to the Nara period when the

government established a road network connecting

the capital at Nara—and later Kyoto—to the

provinces. During the Warring States period, the

road network fell into disrepair and became very

fragmented. In some areas, travel was treacherous, if

not impossible, due to both the bandits who often

found easy prey along the roads, and the barrier sta-

tions meant to restrict access and communication

into and out of domains. It was only in the late 16th

century that military leaders such as Oda Nobunaga

and Toyotomi Hideyoshi recognized the importance

of a functioning road system to their quest for the

unification of Japan. To this end, they inaugurated

efforts to improve the roads and make them safe for

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

328

11.2 Palanquin (Photo William E. Deal)

11.3 Travel by oxcart (Illustration Grace Vibbert)

travel, and to abolish the barrier system, which hin-

dered both mobility and trade.

The subsequent Tokugawa shogunate carried

forward this agenda by establishing a five-road sys-

tem (gokaido) directly maintained by the govern-

ment. These roads were intended to serve the

bureaucratic and military interests of the shogunate

by linking the government’s base at Edo with the

provinces. The Edo-period road system included

not only the five main roads, but many secondary

roads that lead into the five main roads at various

locations. Thus, the Edo period witnessed a dra-

matic increase in travel along roads developed to

handle the traffic created by commerce, pilgrimage,

mandatory domain lord attendance at Edo, and

other travel needs.

FIVE MAIN ROADS

The five main roads developed, controlled, and

maintained by the government were the Tokaido,

Nakasendo, Koshu Kaido, Nikko Kaido, and the

Oshu Kaido (do and kaido mean “road”). The gov-

ernment regulated travel along this road system by

checking the identification of travelers at various

points along the roads. This gave the government a

mechanism for monitoring both travel and commu-

nications between regions. The shogunate required

domain lords to use the five roads in their travels

back and forth from the capital under the alternate-

year attendance edict. All five roads led to and from

a terminal point in Edo, at a bridge known as the

Nihombashi. The Nihombashi area was a center of

commerce during the Edo period.

Tokaido The Tokaido (“Eastern Sea Road”), the

303-mile main road that ran mostly along the coast-

line between Edo and Kyoto, was the most impor-

tant and most traveled of the five roads in the

system. According to period records, the roadbed

consisted of either gravel or stone depending on the

terrain over which the road passed. The average

width of the road was about 18 feet. Travelers mostly

went on foot, though palanquins were used by the

upper classes. Horses were used to carry light goods

and sometimes passengers.

The Tokaido route was serviced by 53 post sta-

tions that attended to the needs of travelers. These

post stations were important because they were busy

with the traffic that moved along this road, and they

later became famous as the subject of a series of

woodblock prints by the noted artist Hiroshige,

called the Fifty-three Stations of the Tokaido Road

(Tokaido gojusantsugi). The post stations from Edo to

Kyoto were:

Start Nihonbashi (Edo)

1 Shinagawa

2 Kawasaki

3 Kanagawa

4 Hodogaya

5 Totsuka

6 Fujisawa

7 Hiratsuka

8 Oiso

9 Odawara

10 Hakone

11 Mishima

12 Numazu

13 Hara

14 Yoshiwara

15 Kanbara

16 Yui

17 Okitsu

18 Ejiri

19 Fuchu

20 Mariko

21 Okabe

22 Fujieda

23 Shimada

24 Kanaya

25 Nissaka

26 Kakegawa

27 Fukuroi

28 Mitsuke

29 Hamamatsu

30 Maisaka

31 Arai

32 Shirasuka

33 Futagawa

34 Yoshida

35 Goyu

36 Akasaka

37 Fujikawa

38 Okazaki

39 Chiryu

T RAVEL AND C OMMUNICATION

329

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

330

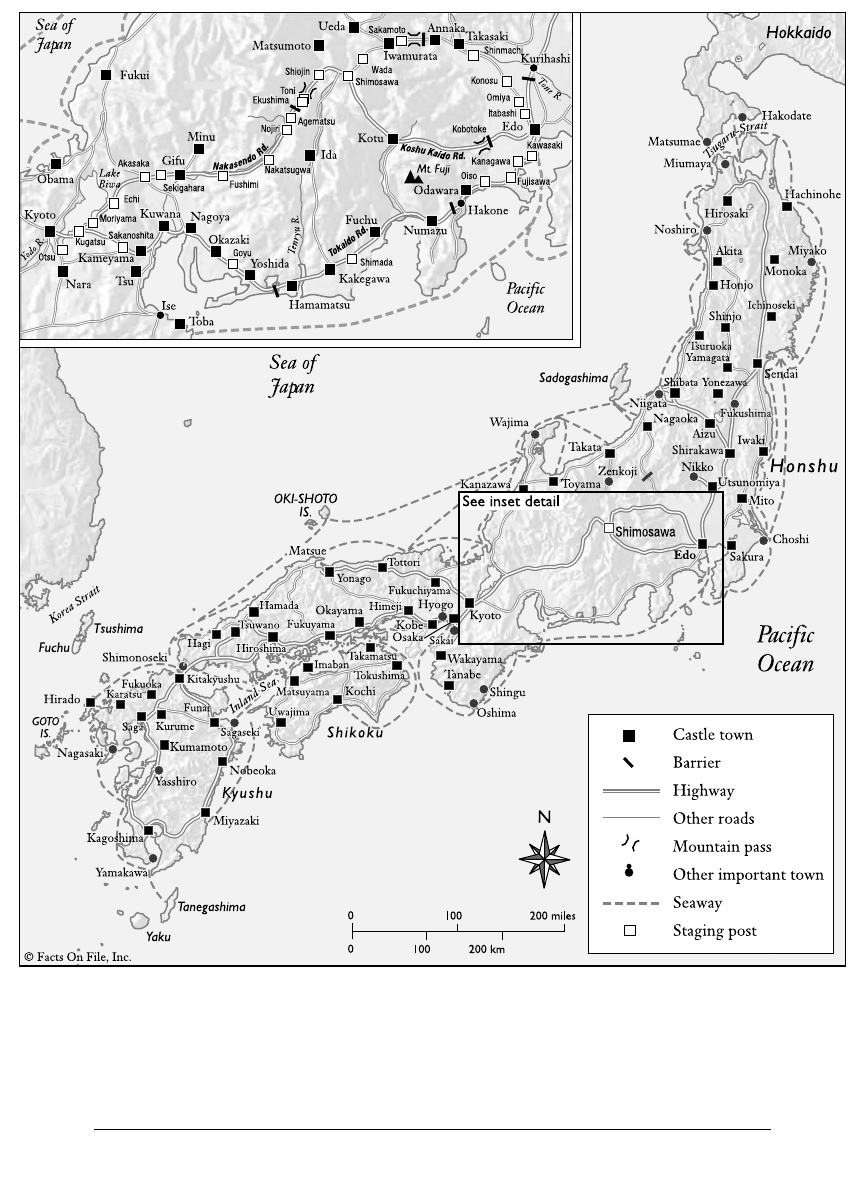

Map 5. Major Roads in the Early Modern Period

40 Narumi

41 Atsuta (Miya)

42 Kuwana

43 Yokkaichi

44 Ishiyakushi

45 Shono

46 Kameyama

47 Seki

48 Sakanoshita

49 Tsuchiyama

50 Minakuchi

51 Ishibe

52 Kusatsu

53 Otsu

End Kyo (Kyoto)

Nakasendo The Nakasendo, also referred to as the

Kiso Kaido or Kisoji, ran some 310 miles between

Edo and Kyoto. Unlike the Tokaido, however, the

Nakasendo traversed an inland course through the

mountains. It was a much more arduous journey,

taking a longer time to complete, and was, as a

result, much less traveled than the Tokaido. The

Nakasendo road went through 67 post stations.

Koshu Kaido The Koshu Kaido, also referred to as

Koshu Dochu, ran for 86 miles from Edo to Shimo-

suwa in Shinano province (present-day Nagano Pre-

fecture) by way of Kofu, with a view of Mt. Fuji. The

road intersected the Tokaido and Nakasendo, link-

ing with the Nakasendo at Shimosuwa. This road

was reportedly the one that Tokugawa Ieyasu con-

ceived of as the shogun’s escape route in the event

that Edo Castle was besieged.

Nikko Kaido The Nikko Kaido, also referred to as

Nikko Dochu, ran 91 miles from Edo north to

Nikko, the site of Tokugawa Ieyasu’s mausoleum, the

Toshogu. The road passed through 21 post stations.

Oshu Kaido The Oshu Kaido, also referred to as

Oshu Dochu, ran 488 miles from Edo north to the

Mutsu and Dewa provinces, terminating at Min-

maya (present-day Aomori Prefecture). The road

started at Edo going north along the same route as

the Nikko Kaido. At the Utsunomiya post station,

the Oshu Kaido branched off, heading farther

north. Past the Shirakawa post station, the shogu-

nate gave control of this road to the various

domains through which it passed, indicating the

extent to which northern Japan was still relatively

underdeveloped and only lightly populated in the

early modern period compared with areas south and

west of Edo.

SECONDARY ROADS

In addition to the five main roads, a system of sec-

ondary roads connected the provinces to the five

main roads. Among the most important of these sec-

ondary roads were the following:

Chugoku Kaido (also referred to by other names,

such as Chugokuji, San’yodo, and Saigoku Kaido):

ran along the Seto Inland Sea from Osaka to Kokura

in Kyushu.

Mito Kaido (also referred to as Mitoji): ran from

Edo northeast to Mito in Hitachi province (present-

day Ibaraki Prefecture).

Sayaji (also referred to as Saya Kaido): ran from

Atsuta (or Miya) in Owari province (present-day Aichi

Prefecture) through the Saya post station and on to

Kuwana in Ise province (present-day Mie Prefecture).

Minoji (also referred to as Mino Kaido): ran from

Nagoya to Ogaki in Mino province (present-day

Gifu Prefecture), connecting the Tokaido at Atsuta

(Miya) to the Nakasendo at Tarui.

Nikko Onari Kaido (or Nikko Onarido) and

the Reiheishi Kaido (or Reiheishido): these two

roads both traversed the space between Edo and

Nikko. Unlike the Nikko Kaido, however, these

roads were only used by government officials in

their pilgrimages to Nikko for ritual services for

Tokugawa Ieyasu at the Toshogu shrine and mau-

soleum.

Iseji (also referred to as Ise Kaido and Sangu

Kaido): ran along the east coast of the Kii peninsula

from Yokkaichi in Ise province (present-day Mie

Prefecture), passing through seven post stations

before arriving at the Ise Shrine.

T RAVEL AND C OMMUNICATION

331

ROAD BUILDING AND

MAINTENANCE

The five main roads were maintained by the Toku-

gawa shogunate. The government issued strict regu-

lations concerning the upkeep of road conditions.

Generally, the shogunate required post stations and

local villages to maintain the roads in their vicinity.

This maintenance included keeping the roads in

good travel condition by removing any debris that

littered the roadbed, patching any potholes, planting

trees along the route, and building and repairing

necessary bridges across rivers. The government

dispatched inspectors along the five main roads to

ensure that maintenance work was properly per-

formed in a timely fashion.

One other important responsibility given to post

stations and local villages was the maintenance of

the milestone marker (ichirizuka; literally, “mile-

stone mounds”) system that provided travelers with

information about their location along the road.

Milestone markers, 10-foot-high square earthen

mounds, measured the distance from Edo in ri,

equivalent to 2.4 miles.

BARRIERS

Although Tokugawa Ieyasu’s predecessors, Oda

Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi, had abolished

the kind of road barriers controlled by local lords

that hindered travel and trade prior to the Edo

period, the Tokugawa shogunate nevertheless insti-

tuted its own system of national barrier stations

(sekisho)—more than 50 on the five main roads—in

order to ascertain the identity of travelers and

ensure they had the proper travel permits. The gov-

ernment was especially concerned with the illegal

movement of warriors and weaponry that might be

used against it. It also sought to maintain the

requirement that the wives and children of domain

lords remain in Edo, and hence was especially suspi-

cious of women and children traveling away from

Edo. The Hakone Barrier, located at the Hakone

Pass south of Edo on the Tokaido, was strictly con-

trolled because the shogunate viewed this particular

area as the most significant point of entry into the

Edo region, and thus in need of special protection

and control.

POST STATIONS

Government-controlled post stations (shukueki)

were situated along roads and offered travelers food,

shelter, and other services. Post stations that were

not directly controlled by the Tokugawa shogunate

were usually run by regional domain lords. The

number of post stations grew over time, and by the

latter part of the Edo period, there were an esti-

mated 250 post stations along the different road sys-

tems. Post stations were spaced at different intervals

depending on the road and terrain. Along the

Tokaido and the Nakasendo, for instance, post sta-

tions were generally located every three to 10 miles.

The size of post stations varied greatly. Some

were very small stations situated in remote mountain

areas that provided only food and lodging. Others

were agricultural villages or market towns. The

largest post stations were located in castle towns.

Even the smaller post stations in rural areas pos-

sessed a more urban feel because of the service-cen-

tered nature of their economies that belied their

location in otherwise agricultural areas.

Services varied at post stations depending on size

and location. In general, post stations included inns

for overnight lodging, restaurants, public baths, pubs,

and shops selling a variety of goods including medi-

cine, clothing, and footwear. Post stations were also

required by government regulation to provide both

packhorses and porters for hire, to facilitate the move-

ment of people and commodities. The movement of

people and goods along roads and through the post

stations was overseen locally by a post station manager

known as a ton’ya. This manager supervised the overall

functioning and efficiency of the post station.

In keeping with social class distinctions that

marked Edo-period society, post stations also institu-

tionalized class hierarchy through the kinds of inns

available to travelers. Inns called honjin (“principal

headquarters”) were available to such elites as domain

lords and their retainers traveling to and from Edo

under the required attendance regulation, as well as

government officials and aristocrats. These upper-

class inns included especially well-appointed rooms

and gardens for the enjoyment of their privileged

guests. Other inns serviced other social classes. There

were inns for lesser government officials and middle-

ranking warriors, as well as inns for commoners.

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

332

MARITIME TRAVEL

AND COMMUNICATION

Domestic waterways, both the seas surrounding the

Japanese islands and the inland freshwater rivers and

lakes, were utilized for warfare, trade, fishing, pas-

senger transport, and leisure activities. Similarly, the

seas beyond Japan’s immediate shores were used for

trade, transporting government officials on missions,

and warfare. The seas were also a source of anxiety

because they brought potential enemies—as they did

with the late 13th-century Mongol invasions—and if

not enemies, then contacts with societies that pre-

sented challenges to Japan’s status quo—as occurred

when the Jesuits appeared in the mid 16th century

and when Admiral Perry arrived in 1853.

Maritime travel was also intimately linked to

issues of communication. Trends and fashions in one

Japanese city were communicated to another by

virtue of the maritime trade that moved both mater-

ial goods and various aspects of culture, including

music, theater, and literature. Similarly, in addition

to commodities, Chinese cultural values were com-

municated to Japan as a result of trade and diplo-

matic relations conveyed by ship. These cultural

commodities included ideas about government, reli-

gion, morality, and the arts. Finally, it was the image

of the “black ships” of Admiral Perry that signaled

the final years of the Tokugawa shogunate and the

end of the early modern period. These ships, and

those that followed from other Western countries,

communicated the foreign interest in—and insis-

tence on—having Japan as a trading partner.

This section examines the historical importance of

domestic and international maritime travel and the

ships that undertook these voyages. Specific water-

ways are covered in chapter 2: Land, Environment,

and Population, and specific economic developments

that spurred the use of waterways to conduct trade are

treated in chapter 4: Society and Economy.

Medieval Maritime Travel

and Communication

In medieval Japan, ships plied both local and interna-

tional waters to conduct trade. In many ways, the

more remarkable achievement was in international

T RAVEL AND C OMMUNICATION

333

11.4 Model of an Edo-period riverboat (Edo-Tokyo Museum exhibit; Photo William E. Deal)