Duiker William J., Spielvogel Jackson J. The Essential World History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

very mournful songs about the nativity and the passion of

Our Lord. The object of this penance was to put a stop to

the mortality, for in that time ...at least a third of all the

people in the world died.

7

The flagellants created mass hysteria wherever they went,

and authorities worked overtime to crush the movement.

An outbreak of virulent anti-Semitism also accom-

panied the Black Death. Jews were accused of causing the

plague by poisoning town wells. The worst pogroms

against this minority were carried out in Germany, where

more than sixty major Jewish communities had been

exterminated by 1351 (see the box above). Many Jews fled

eastward to Russia and especially to Poland, where the

king offered them protection. Thus, eastern Europe be-

came home to large Jewish communities.

Economic Dislocation and Social Upheaval

The deaths of so many people in the fourteenth century

also had sever e economic consequences. Trade declined,

and some industries suffered greatly. A shortage of work ers

caused a dramatic rise in the price of labor , while the de-

cline in the number of people lowered the demand for

food, resulting in falling prices. Landlords were now paying

more for labor at the same time that their re ntal income

was declining. Concurrently, the decline in the number of

peasants after the Black Death made it easier for some to

con vert their labor services to rent, thus freeing them from

serfdom. But there were limits to how much the peasants

could advance. They faced the same economic hurdles as the

lords, who also attempted to impose wage restrictions and

reinstate old forms of labor service. P easant complaints

became widespread and soon gave rise to rural rev olts.

Although the peasant rev olts sometimes resulted in

short-term gains for the participants, the uprisings were easily

crushed and their gains quickly lost. A ccustomed to ruling,

the established classes easily combined and stifled dissent.

Political Instability

Famine, plague, economic turmoil, and social upheaval

were not the only problems of the fourteenth century.

THE CREMATION OF THE STRASBOURG JEWS

In their attempt to explain the widespread horrors

of the Black Death, medieval Christian communi-

ties looked for scapegoats. As at the time of the

Crusades, the Jews were accused of poisoning

wells and hence spreading the plague. This selection by a con-

temporary chronicler, written in 1349, gives an account of how

Christians in the town of Strasbourg in the Holy Roman Empire

dealt with their Jewish community. It is apparent that financial

gain was also an important factor in killing the Jews.

Jacob von K

€

onigshofen, ‘‘The Crema tion

of the Strasbourg Jews’’

In the year 1349 there occurred the greatest epidemic that ever hap-

pened. Death went from one end of the earth to the other. ... And

from what this epidemic came, all wise teachers and physicians

could only say that it was God’s will. ... This epidemic also came

to Strasbourg in the summer of the above-mentioned year, and it is

estimated that about sixteen thousand people died.

In the matter of this plague the Jews throughout the world were

reviled and accused in all lands of having caused it through the poi-

son which they are said to have put into the water and the wells---that

is what they were accused of---and for this reason the Jews were burnt

all the way from the Mediterranean into Germany. ...

[The account then goes on to discuss the situation of the Jews

in the city of Strasbourg.]

On Saturday ...they burnt the Jews on a wooden platform in

their cemetery. There were about two thousand people of them.

Those who wanted to baptize themselves were spared. [Some say

that about a thousand accepted baptism.] Many small children were

taken out of the fire and baptized against the will of their fathers

and mothers. And everything that was owed to the Jews was can-

celed, and the Jews had to surrender all pledges and notes that they

had taken for debts. The council, however, took the cash that the

Jews possessed and divided it among the workingmen proportion-

ately. The money was indeed the thing that killed the Jews. If they

had been poor and if the feudal lords had not been in debt to them,

they would not have been burnt. ...

Thus were the Jews burnt at Strasbourg, and in the same year

in all the cities of the Rhine, whether Free Cities or Imperial Cities

or cities belonging to the lords. In some towns they burnt the Jews

after a trial; in others, without a trial. In some cities the Jews them-

selves set fire to their houses and cremated themselves.

It was decided in Strasbourg that no Jew sho uld enter the

city for a hundred years, but before twenty years had passed,

the council and magistrates agreed that they ought to admit the

Jews again into the city for twenty years. And so the Jews came

back again to Strasbourg in the year 1368 after the bir th of our

Lord.

Q

What charges were made against the Jews in regard to the

Black Death? Can it be said that these charges were economi-

cally motivated? Why or why not? Why did the anti-Semitism of

towns such as Strasbourg lead to the establishment of large

Jewish populations in eastern Europe?

324 CHAPTER 13 THE BYZANTINE EMPIRE AND CRISIS AND RECOVERY IN THE WEST

War and political instability must also be added to the

list. Of all the struggles that ensued in the fourteenth

century, the Hundred Years’ War was the most violent.

The Hundred Year s’ War In the thirteenth century,

England still held one small possession in France known

as the duchy of Gascony. As duke of Gascony, the English

king pledged loyalty as a vassal to the French king, but

when King Philip VI of France (1328--1350) seized Gas-

cony in 1337, the duke of Gascony---King Edward III of

England (1327--1377)---declared war on Philip.

The Hundred Years’ War began in a burst of knightly

enthusiasm. The French army of 1337 still relied largely on

heavily armed noble cavalrymen, who looked with con-

tempt on foot soldiers and crossbowmen, whom they

regarded as social inferiors. The English, too, used heavily

armed cavalry, but they relied even more on large num-

bers of paid foot soldiers. Armed with pikes, many of these

soldiers had also adopted the longbow, invented by the

Welsh. The longbow had greater striking power, longer

range, and more rapid speed of fire than the crossbow.

The first major battle of the Hundred Years’ War

occurred in 1346 at Cr

ecy, just south of Flanders. The

larger French army followed no battle plan but simply

attacked the English lines in a disorderly fashion. The

arrows of the English archers decimated the French cav-

alry. As the chronicler Froissart described it, ‘‘[With their

longbows] the English continued to shoot into the

thickest part of the crowd, wasting none of their arrows.

They impaled or wounded horses and riders, who fell to

the ground in great distress, unable to get up again

without the help of several men.’’

8

It was a stunning

victory for the English and the foot soldier.

The Battle of Cr

ecy was not decisive, however. The

English simply did not possess the resources to subjugate all

of Franc e, but they continued to try . The English king,

Henry V (1413--1422), was especially eager to achieve vic-

tory . At the Battle of Agincourt in 1415, the heavy, armor-

plated French knights attempted to attack across a field

turned to mud b y heavy rain; the result was a disastrous

French defeat and the death of fifteen hundred French

nobles. The English were masters of northern France.

The seemingly hopeless French cause then fell into the

hands of the dauphin Charles, the heir to the throne, who

governed the southern two-thirds of French lands. Charles’s

cause seemed doomed until a French peasant woman

quite unexpectedly saved the timid monarch. Born in

1412, the daughter of well-to-do peasants, Joan of Arc

was a deeply religious person who came to believe that

her favorite saints had commanded her to free France. In

February 1429, Joan made her way to the dauphin’s court

and persuaded Charles to allow her to accompany a

French army to Orl

eans. Apparently inspired by the faith

of the peasant girl called ‘‘the Maid of Orl

eans,’’ the

French armies found new confidence in themselves and

liberated Orl

eans and the entire Loire valley.

But Joan did not live to see the war concluded.

Captured in 1430, she was turned over the Inquisition on

charges of witchcraft. In the fifteenth century, spiritual

visions were thought to be inspired by either God or the

devil. Joan was condemned to death as a heretic and

burned at the stake in 1431. Twenty-five years later, a new

ecclesiastical court exonerated her of these charges, and

five centuries later, in 1920, she was made a saint of the

Roman Catholic Church.

Joan of Arc’s accomplishments proved decisive. Al-

though the war dragged on for another two decades,

defeats of English armies in Normandy and Aquitaine led

to French victory by 1453. Important to the French

success was the use of the cannon, a new weapon made

possible by the invention of gunpowder. The Chinese had

invented gunpower in the eleventh century and devised a

simple cannon by the thirteenth century. The Mongols

greatly improved this technology, developing more ac-

curate cannons and cannonballs; both spread to the

Middle East in the thirteenth century and to Europe by

the fourteenth. The use of gunpowder eventually brought

drastic changes to European warfare by making castles,

city walls, and armored knights obsolete.

Political Disintegration By the fourteenth century, the

feudal order had begun to break down. With money from

taxes, kings could now hire professional soldiers, who

tended to be more reliable than feudal knights anyway.

Fourteenth-century kings had their own problems, how-

ever. Many dynasties in Europe failed to produce male

heirs, and the founders of new dynasties had to fight for

their positions as groups of nobles, trying to gain ad-

vantages for themselves, supported opposing candidates.

Rulers encountered financial problems, too. Hiring pro-

fessional soldiers left them always short of cash, adding

yet another element of uncertainty and confusion to

fourteenth-century politics.

The Decline of the Church

The papacy of the Roman Catholic Church reached the

height of its power in the thirteenth century. But prob-

lems in the fourteenth century led to a serious decline for

the church. By that time, the monarchies of Europe were

no longer willing to accept papal claims of temporal su-

premacy, as is evident in the struggle between Pope

Boniface VIII (1294--1303) and King Philip IV of France.

In need of new revenues, Philip claimed the right to tax

the clergy of France, but Boniface VIII insisted that the

clergy of any state could not pay taxes to their secular

THE CRISES OF THE FOURTEENTH CENTURY 325

ruler without the consent of the pope, who, he argued,

was supreme over both the church and the state.

Philip IV refused to accept the pope ’s position and

sent French forces to capture Boniface and bring him back

to F rance for trial. The pope escaped but soon died fr om

the shock of his experience. To ensure his position, Philip

IV engineered the election of a Frenchman, Clement V

(1305--1314), as pope. The new pope took up residence in

Avignon on the east bank of the Rhone River.

From 1305 to 1377, the popes resided in Avignon,

leading to an increase in antipapal sentiment. The pope

was the bishop of Rome, and it was unseemly that the head

of the Catholic church should reside in Avignon instead of

Rome. Moreo v er, the splendor in which the pope and

cardinals were living in Avignon led to highly vocal criti-

cism of the papacy . At last, Pope Gregory XI (1370--1378),

perc eiving the disastrous decline in papal prestige, returned

to Rome in 1377, but died there the spring after his return.

When the college of cardinals met to elect a new pope,

the citizens of Rome threatened that the cardinals would

not leav e Rome alive unless they elected an Italian as pope.

Wisely, the terrified cardinals duly elected the Italian

archbishop of Bari as Pope Urban VI (1378--1389). Five

months later, however, a group of French cardinals de-

clared Urban’s election invalid and chose a Frenchman as

pope, who promptly returned to Avignon. Because Urban

remained in Rome, there were now two popes, beginning

what has been called the Great Schism of the church.

The Great Schism divided Europe. France and its al-

lies supported the pope in Avignon, whereas France’s

enemy England and its allies supported the pope in Rome.

The Great Schism was also damaging to the faith of

Christian believers. The pope was widely believed to be the

true leader of Christendom; when both lines of popes

denounced the other as the Antichrist, people’ s faith in the

papacy and the church was undermined. Finally, a church

council met at Constance, Switzerland, in 1417. After the

competing popes resigned or were deposed, a new pope

was elected who was acceptable to all parties.

By the mid-fifteenth century, as a result of these

crises, the church had lost much of its temporal power.

Even worse, the papacy and the church had also lost

much of their moral prestige.

Recovery: The Renaissance

Q

Focus Question: What were the main features of the

Renaissance in Europe, and how did it differ from the

Middle Ages?

People who lived in Italy between 1350 and 1550 or so

believed that they were witnessing a rebirth of Classical

antiquity---the world of the Greeks and Romans. To them,

this marked a new age, which historians later called the

Renaissance (French for ‘‘rebirth’’) and viewed as a dis-

tinct period of European history, which began in Italy and

then spread to the rest of Europe.

Renaissance Italy was largely an urban society. The

city-states became the centers of Italian political, eco-

nomic, and social life. Within this new urban society, a

secular spirit emerged as increasing wealth created new

possibilities for the enjoyment of worldly things.

The Renaissance was also an age of recovery from the

disasters of the fourteenth century, including the Black

Death, political disorder, and economic recession. In

pursuing that recovery, Italian intellectuals became in-

tensely interested in the glories of their own past, the

Greco-Roman culture of antiquity.

A new view of human beings emerged as people in

the Italian Renaissance began to emphasize individual

ability. The fifteenth-century Florentine architect Leon

Battista Alberti expressed the new philosophy succinctly:

‘‘Men can do all things if they will.’’

9

This high regard for

human worth and for individual potentiality gave rise to

a new social ideal of the well-rounded personality or

‘‘universal person’’ (l’uomo universale) who was capable of

achievements in many areas of life.

The Intellectual Renaissance

The emergence and growth of individualism and secu-

larism as characteristics of the Italian Renaissance are

most noticeable in the intellectual and artistic realms. The

most important literary movement associated with the

Renaissance is humanism.

Renaissance humanism was an intellectual move-

ment based on the study of the classics, the literary works

of Greece and Rome. Humanists studied the liberal arts---

grammar, rhetoric, poetry, moral philosophy or ethics,

and history---all based on the writings of ancient Greek

and Roman authors. We call these subjects the humanities.

Petrarch (1304--1374), who has often been called the

father of Italian Renaissanc e humanism, did more than any

other individual in the fourteenth century to foster its de-

velopment. P etrar ch sought out forgotten Latin manuscripts

and also began the humanist emphasis on the use of pure

Classical Latin. Humanists used the works of Cicero as a

model for prose and those of V irgil for poetry . As P etrarch

said, ‘‘Christ is my God; Cicero is the prince of the language.’’

In Florence, the humanist movement took a new

direction at the beginning of the fifteenth century. The

humanists who worked as secretaries for the city council

of Florence took a new interest in civic life. They came to

believe that intellectuals had a duty to live an active life

for their state and that their study of the humanities

should be put to the service of the state.

326 CHAPTER 13 THE BYZANTINE EMPIRE AND CRISIS AND RECOVERY IN THE WEST

Also evident in the humanism of the first half of the

fifteenth century was a growing interest in Classical Greek

civilization. One of the first Italian humanists to gain a

thorough knowledge of Greek was Leonar do Bruni, who

became an enthusiastic pupil of the Byzantine scholar Manuel

Chrysoloras, who taught in Florenc e from 1396 to 1400.

The Artistic Renaissance

Renaissance artists sought to imitate nature in their works

of art. Their search for naturalism became an end in itself:

to persuade onlookers of the reality of the object or event

they were portraying. At the same time, the new artistic

standards reflected the new attitude of mind in which

human beings became the focus of attention, the ‘‘center

and measure of all things,’’ as one artist proclaimed.

This new Renaissance st yle was developed by Flor-

entine painters in the fifteenth century. Especially im-

portant were two major developments. One emphasized

the technical side of painting---understanding the laws of

perspective and the geometrical organization of outdoor

space and light. The second development was the in-

vestigation of movement and anatomical structure. The

realistic portrayal of the human nude became one of the

foremost preoccupations of Italian Renaissance art.

By the end of the fifteenth century, Italian artists had

mastered the new techniques for scientific observation of

the world around them and were ready to move into new

forms of creative expression. This marked the shift to the

High Renaissance, which was dominated by the work of

three artistic giants, Leonardo da Vinci (1452--1519),

Raphael (1483--1520), and Michelangelo (1475--1564).

Leonardo carried on the fifteenth-century experimental

tradition by studying everything and even dissecting

human bodies in order to see how nature worked. But

Leonardo also stressed the need to advance beyond such

realism and initiated the High Renaissance’s preoccupa-

tion with the idealization of nature, an attempt to gen-

eralize from realistic portrayal to an ideal form.

At twenty-five, Raphael was already regarded as one

of Italy’s best painters. He was acclaimed for his numerous

madonnas, in which he attempted to achieve an ideal of

beauty far surpassing human standards. He is well known

for his frescoes in the Vatican Palace, which reveal a world

of balance, harmony, and order---the underlying principles

of the Classical art of Greece and Rome.

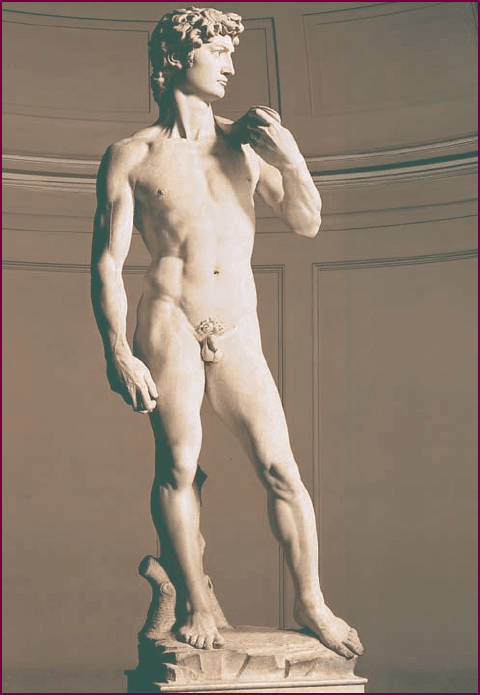

Michelangelo, an accomplished painter, sculptor , and

architect, was fiercely driv en by a desire to create, and he

work ed with great passion and energy on a remarkable

number of projects. Michelangelo was influenced by

Neoplatonism, which viewed the ideal beauty of the hu-

man form as a reflection of divine beauty; the more

beautiful the body, the more God-like the figur e. Another

manifestation of Michelangelo ’s search for ideal beauty was

his David, a colossal marble statue commissioned by the

government of Florence in 1501 and c ompleted in 1504.

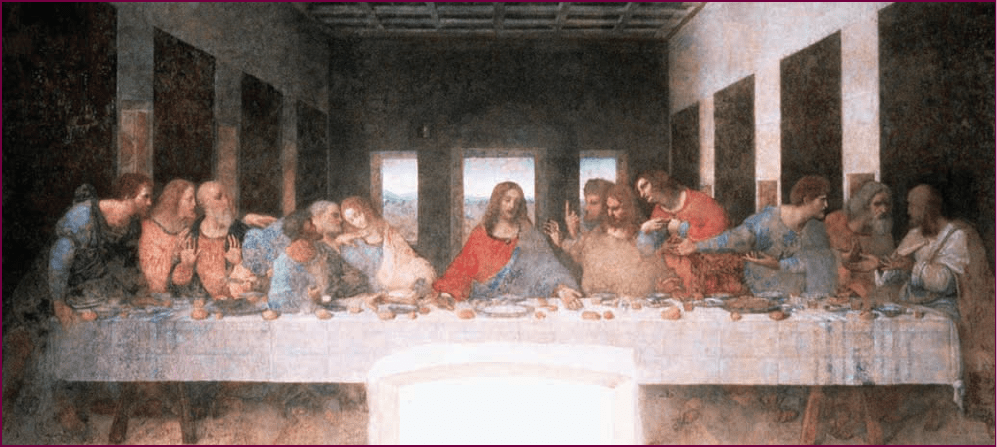

Leonardo da Vinci, Th e La st Sup per. Leonardo da Vinci was the impetus behind the High Renaissance

interest in the idealization of nature, moving from a realistic portrayal of the human figure to an idealized form.

Evident in Leonardo’s Last Supper is his effort to depict a person’s character and inner nature by the use of

gesture and movement. Unfortunately, Leonardo used an experimental technique in this fresco, which soon led

to its physical deterioration.

c

Scala/Art Resource

RECOVERY:THE RENAISSANCE 327

The State in the Renaissance

In the second half of the fifteenth century, attempts were

made to reestablish the centralized power of monarchical

gove rnments after the political disasters of the fourteenth

century. Some historians called these states the ‘‘new mon-

archies,’’ especially those of France, England, and Spain.

The Italian States The Italian states provided the ear-

liest examples of state building in the fifteenth century.

During the Middle Ages, Italy had failed to develop a

centralized territorial state, and by the fifteenth century,

five major powers dominated the Italian peninsula: the

duchy of Milan, the republics of Florence and Venice, the

Papal States, and the kingdom of Naples.

Milan, Florence, and Venice proved especially adept

at building strong, centralized states. Under a series of

dukes, Milan became a highly centralized territorial state

in which the rulers devised systems of taxation that

generated enormous revenues for the government. The

maritime republic of Venice remained an extremely sta-

ble political entity governed by a small oligarchy of

merchant-aristocrats. Its commercial empire brought in

vast revenues and gave it the status of an international

power. In Florence, Cosimo de’ Medici took control of

the merchant oligarchy in 1434. Through lavish pa-

tronage and careful courting of political allies, he and his

family dominated the city at a time when Florence was

the center of the cultural Renaissance.

As strong as these Italian states became, they still

could not compete with the powerful monarchical states

to the north and west. Beginning in 1494, Italy became a

battlefield for the great power struggle between the

French and Spanish monarchies, a conflict that led to

Spanish domination of Italy in the sixteenth century.

Western Europe The Hundred Years’ War left France

prostrate. But it had also engendered a certain degree of

French national feeling toward a common enemy that the

kings could use to reestablish monarchical power. The

development of a French territorial state was greatly ad-

vanced by King Louis XI (1461--1483), who strengthened

the use of the taille---an annual direct tax usually on land

or property---as a permanent tax imposed by royal au-

thority, giving him a sound, regular source of income and

creating the foundations of a strong French monarchy.

As the first Tudor king, Henry VII (1485--1509)

worked to establish a strong monarchical government in

England. Henry ended the petty wars of the nobility by

abolishing their private armies. He was also very thrifty.

By not overburdening the nobility and the middle class

with taxes, Henry won their favor, and they provided him

much support.

Spain, too, experienced the growth of a strong na-

tional monarchy by the end of the fifteenth century.

During the Middle Ages, several independent Christian

kingdoms had emerged in the course of the long recon-

quest of the Iberian peninsula from the M uslims. Two of the

strongest were Aragon and Castile. When Isabella of Castile

(1474--1504) married F erdinand of Aragon (1479--1516) in

1469, it was a major step toward unifying Spain. The tw o

rulers worked to strengthen royal control of government.

They filled the royal council with middle-class lawyers who

operated on the belief that the monar ch y embodied the

power of the state. Ferdinand and Isabella also reorganized

the military forces of Spain, making the new Spanish army

thebestinEuropebythesixteenthcentury.

Central and Eastern Europe Unlike France, England,

and Spain, the Holy Roman Empire failed to develop a

Michelangelo , David. This statue of David, cut from an 18-foot-high

block of marble, exalts the beauty of the human body and is a fitting

symbol of the Italian Renaissance’s affirmation of human power.

Completed in 1504, David was moved by Florentine authorities to a special

location in front of the Palazzo Vecchio, the seat of the Florentine

government.

c

Snark/Art Resource, NY

328 CHAPTER 13 THE BYZANTINE EMPIRE AND CRISIS AND RECOVERY IN THE WEST

strong monarchical authorit y. The failure of the Ger-

man emperors in the thirteenth century ended any

chance of centralized monarchical authority, and Ger-

many became a land of hundreds of vir tually indepen-

dent states. After 1438, the position of Holy Roman

emperor was held by members of the Habsburg dynasty.

Having gradually acquired a n umber of possessions

along the Danube, known collectively as Austria, the

house of Habsburg had become one of the wealthiest

landholders in the empire.

In eastern Europe, rulers struggled to achieve the

centralization of the territorial states. Religious differences

troubled the area, as Roman Catholics, Eastern Orthodox

Christians, and other groups, including the Mongols,

confronted each other. In Poland, the nobles gained the

upper hand and established the right to elect their kings, a

policy that drastically weakened royal authority.

Since the thirteenth century, Russia had been under

the domination of the Mongols. Gradually, the princes of

Moscow rose to prominence by using their close rela-

tionship to the Mongol khans to increase their wealth and

expand their possessions. During the reign of the great

Prince Ivan III (1462--1505), a new Russian state was

born. Ivan annexed other Russian principalities and took

advantage of dissension among the Mongols to throw off

their yoke by 1480.

TIMELINE

500

700 900 1100 1300

1500

Byzantine

Empire

Reign of Justinian

Europe

First Crusade

Fourth Crusade

Hundred Years' War

Great Schism

Works of

Leonardo da Vinci

Arab defeat of Byzantines

at Yarmuk

Leo VI

Schism between Eastern

Orthodox Church and

Roman Catholic Church

Turkish defeat of Byzantines

at Manzikert

Latin Empire of Constantinople

Ottoman Turks

seize Constantinople

CONCLUSION

AFTER THE COLLAPSE of Roman power in the west, the

eastern Roman Empire, centered on Constantinople, continued

in the eastern Mediterranean and eventually emerged as the

Byzantine Empire, which flourished for hundreds of years. While

a new Christian civilization arose in Europe, the Byzantine

Empire created its own unique Christian civilization. And while

Europe struggled in the Early Middle Ages, the Byzantine world

continued to prosper and flourish. Especially during the ninth,

tenth, and eleventh centuries, under the Macedonian emperors,

the Byzantine Empire expanded and achieved an economic

CONCLUSION 329

SUGGESTED READING

General Histories of the Byzantine Empire For

comprehensive sur veys of the Byzantine Empire, see T. E. Gregory,

A History of Byzantium (Oxford, 2005), and W. Treadgold, A

History of the Byzantine State and Society (Stanford, Calif., 1997).

See also C. Mango , ed., The Oxford History of Byz antium (Oxford,

2002). Brief but good introductions to Byzantine history can be found

in J. Haldon, Byzantium: A History (Charleston, S.C., 2000), and

W. Treadgold, A Concise History of Byzantium (London, 2001). For a

thematic approach, see A. Cameron, The Byzantines (Oxford, 2006).

The Early Empire (to 1025) Byzantine civilization in this

period is examined in M. Whittow, The Making of Orthodox

Byzantium, 600--1025 (Berkeley, Calif., 1996). On Justinian, see

J. Moorhead, Justinian (London, 1995), and J. A. S. Evans, The Age

of Justinian (New York, 1996). On Theodora, see P. Cesaretti,

Theodora, Empress of Byzantium, trans. R. M. Frongia (New York,

2004). On Constantinople, see J. Harris, Constantinople: Capital

of Byzantium (London, 2007). The role of the Christian church is

discussed in J. Hussey, The Orthodox Church in the Byzantine

Empire (Oxford, 1986). Women in the Byzantine Empire are

examined in C. L. Connor, Women of Byzantium (New Haven,

Conn., 2004), and J. Herrin, Women in Purple: Rulers of Medieval

Byzantium (Princeton, N.J., 2001). On economic affairs, see

A. Harvey, Economic Expansion in the Byzantine Empire, 900--1200

(Cambridge, 1990). Art is examined in T. F. Mathews, The Art

of Byzantium: B etween Antiquity and the Renaissance (London,

1998).

The Late Empire (1025--1453) On the eleventh and twelfth

centuries, see M. Angold, The Byzantine Empire, 1025--1204, 2nd

ed. (London, 1997). The impact of the Crusades on the Byzantine

Empire is examined in J. Harris, Byzantium and the Crusades

(London, 2003). The disastrous Fourth Crusade is examined in

J. Philips, The Fourth Crusade and the Sack of Constantinople

(New York, 2004). On the fall of Constantinople, see D. Nicolle,

J. Haldon, and S. Turnbull, The Fall of Constantinople: The

Ottoman Conquest of Byzantium (Oxford, 2007).

Crises of the Fourteenth Century On the Black Death, see

J. Kelly, The Great Mortality (New York, 2005), and D. J. Herlihy,

The Black Death and the Transformation of the West, ed. S. K.

Cohn Jr. (Cambridge, Mass., 1997). A worthy account of the

Hundred Years’ War is A. Curry, The Hundred Years’ War, 2nd ed.

(New York, 2004). On Joan of Arc, see M. Warner, Joan of Arc: The

Image of Female Heroism (New York, 1981).

The Renaissance General works on the Renaissance in Europe

include P. B ur k e , The European Renaissance: Centres and Peripheries

(Oxford, 1998); M. L. King, The Renaissance in Europe (New York,

2004); and J. R. Hale, The Civilization of Europe in the R enaissance

(New York, 1994). A brief introduction to Renaissance humanism can

be found in C. G. Nauert Jr., Humanism and the Culture of

Renaissance Europe, 2nd ed. (Cambridge, 2006). Good surveys of

Renaissance art include R. Turner, Renaissance Florence: The

Invention of a New Art (New York, 1997), and J. T . Paoletti and

G. M. Radke, Art, Power, and Patronage in Renaissance Italy, 3rd ed.

(Upper Saddle River, N.J ., 2003). For a general work on the political

development of Europe in the Renaissance, see C. Mulgan, The

Renaissance Monarchies, 1469--1558 (Cambridge, 1998). A good

study of the Italian states is J. M. Najemy, Italy in the Age of the

Renaissance, 1300--1550 (Oxfor d, 2004).

prosperity that was evident to foreign visitors who frequently

praised the size, wealth, and physical surroundings of the central

city of Constantinople.

During its heyday, Byzantium was a multicultural and

multiethnic empire that ruled a remarkable number of peoples

who spoke different languages. Byzantine cultural and religious

forms spread to the Balkans, parts of central Europe, and Russia.

Byzantine scholars spread the study of the Greek language to Italy,

expanding the Renaissance humanists’ knowledge of Classical

Greek civ ilization. The Byzantine Empire also interacted with the

worl d of Islam to its east and the new Euro pean civilization of the

west. Both interactions prove d costly and ultimately fatal.

Although European civiliz ation and Byzan tine civilization shared a

common bond in Christianity, it proved incapable of keeping

them in harmony politically. Indeed, the west’s Crusades to

Palestine, ostensibly for religious motives, led to western control of

the Byzantine Empire from 1204 to 1261. Although the empire was

restored, it limped along until its other interaction---with the

Muslim world---led to its demise when the Ottoman Turks

conquered the city of Constantinople and made it the center of

their new empire.

While Byzantium was declining in the twelfth and thir teenth

centurie s, Europe was achieving new levels of growth and

optimism. In the fourteenth centu ry, however, Euro pe too

experienced a time of troubles as it was devastated by the Black

Death, economic dislocation, political chaos, and religious decline.

But in the fifteenth century, while Constantinople and the

remnants of t he Byzantine Empire finally fell to the world of Islam,

Europe experienced a dramatic revival. Elements of recovery in the

Renaissance made the fifteenth century a period of significant

artistic, intellectual, and political change in Europe. By the second

half of the fifteenth centur y, as we shall see in the next chapter, the

growth of strong, centralized monarchical states made possible the

dramatic expansion of Europe into other parts of t he world.

Visit the website for The Essential World History to access study

aids such as Flashcards, Critical Thinking Exercises, and

Chapter Quizzes:

www.cengage.com/history/duikspiel/essentialworld6e

330 CHAPTER 13 THE BYZANTINE EMPIRE AND CRISIS AND RECOVERY IN THE WEST

331

PART

III

T

HE

E

MERGENCE OF

N

EW

W

ORLD

P

ATTERNS

(1500--1800)

14 NEW ENCOUNTERS:THE CREATION

OF A

WORLD MARKET

15 EUROPE TRANSFORMED:REFORM

AND

STATE BUILDING

16 THE MUSLIM EMPIRES

17 THE EAST ASIAN WORLD

18 THE WEST ON THE EVE OF A

NEW WORLD ORDER

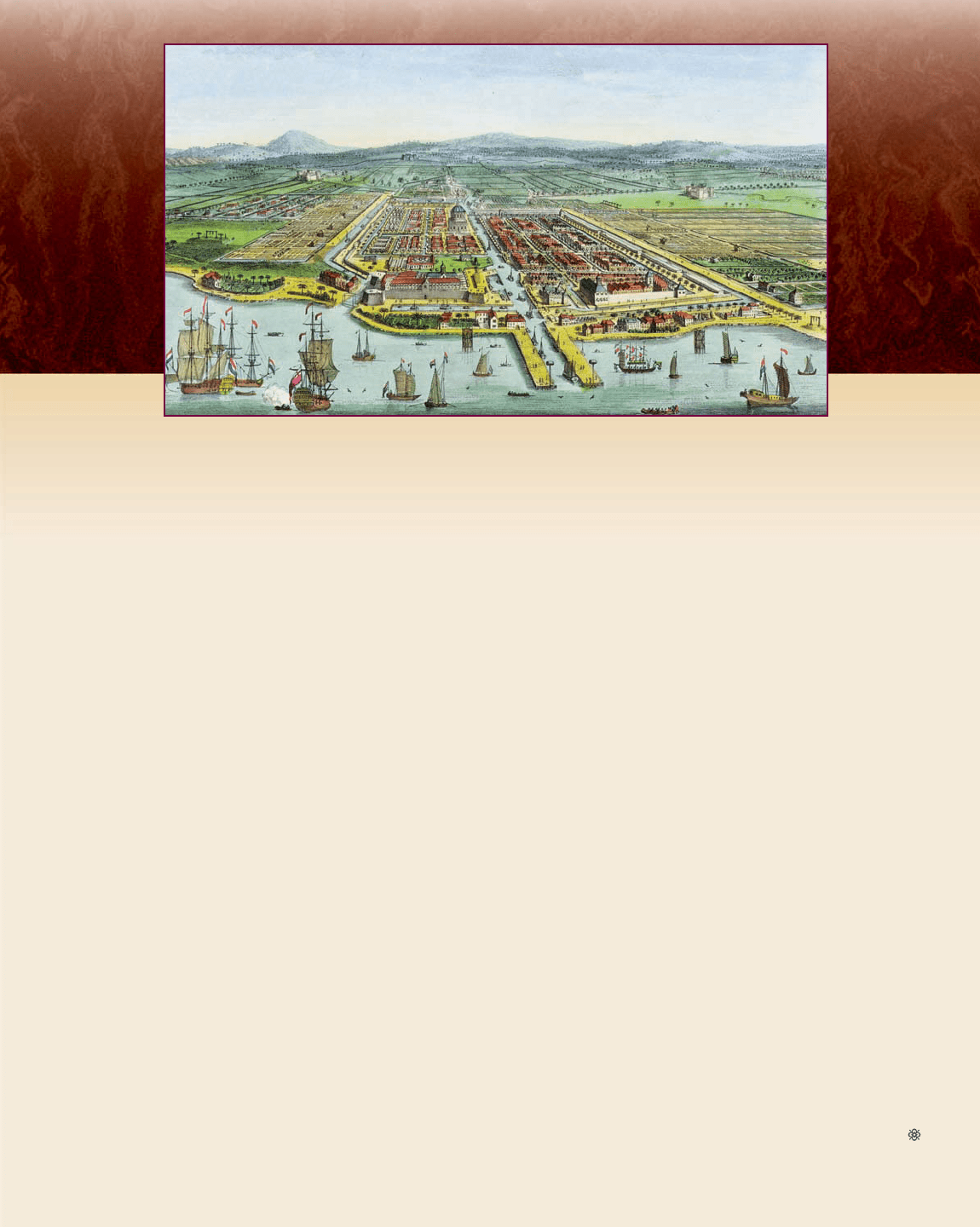

HISTORIANS OFTEN REFER to the period fr om the sixteenth

through eighteenth centuries as the early modern era. During these years,

several factors were at work that created the conditions of our own time.

From a global perspective, perhaps the most noteworthy event of

the period was the extension of the maritime trade network throughout

the entire populated world. The Chinese had inaugurated the process

with their groundbreaking voyages to East Africa in the early fifteenth

century. Muslim traders had contributed their part by extending their

mercantile network as far as China and the Spice Islands in Southeast

Asia. The final instrument of that expansion was a resurgent Europe,

which exploded onto the world scene with the initial explorations of

the Portuguese and the Spanish at the end of the fifteenth century and

then gradually came to dominate shipping on international trade

routes during the next three centuries.

Some contemporary historians argue that it was this sudden burst

of energy from Europe that created the first truly global economic

network. According to Immanuel Wallerstein, one of the leading pro-

ponents of this theory, the Age of Exploration led to the creation of a

new ‘‘world system’’ characterized by the emergence of global trade

networks dominated by the rising force of European capitalism, which

now began to scour the periphery of the system for access to markets

and cheap raw materials.

Other historians, however, qualify Wallerstein’s view and point to

the Mongol expansion beginning in the thirteenth century or even to the

rise of the Arab Empire in the Middle East a few centuries earlier as signs

of the creation of a global communications network enabling goods and

ideas to travel from one end of the Eurasian supercontinent to the other.

Whatever the truth of this debate, there are still many reasons for

considering the end of the fifteenth century as a crucial date in world

history. In the most basic sense, it marked the end of the long isolation

of the Western Hemisphere from the rest of the inhabited world. In so

doing, it led to the creation of the first truly global network of ideas and

commodities, which would introduce plants, ideas, and (unfortunately)

many new diseases to all humanity (see the comparative essay in

Chapter 14). Second, the period gave birth to a stunning increase in

trade and manufacturing that stimulated major economic changes not

only in Europe but in other parts of the world as well.

The period from 1500 to 1800, then, was an incubation period for

the modern world and the launching pad for an era of European

domination that would reach fruition in the nineteenth century. To

understand why the West emerged as the leading force in the world at

that time, it is necessary to grasp what factors were at work in Europe

and why they were absent in other major civilizations around the globe.

Historians have identified improvements in navigation, shipbuild-

ing, and weaponry that took place in Europe in the early modern era as

essential elements in the Age of Exploration. As we have seen, man y of

these technological advances were based on earlier disco v eries that had

taken place elsewher e---in China, India, and the Middle East---and had

332

then been brought to Europe on Muslim ships or along the trade routes

through Central Asia. But it was the capacity and the desire of the

Eur opeans to enhance their wealth and power by making practical use of

the discov eries of others that was the significant factor in the equation

and enabled them to dominate international sea-lanes and create vast

colonial empires in the Western Hemisphere.

European expansion was not fueled solely by economic consid-

erations, however. As had been the case with the rise of Islam, religion

played a major role in motivating the European Age of Exploration in the

early modern era. Although Christianity was by no means a new religion

in the sixteenth century (as Islam had been at the moment of Arab

expansion), the world of Christendom was in the midst of a major period

of conflict with the forc es of Islam, a rivalry that had been exacerbated by

the conquest of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottoman Turks in 1453.

Although the claims of Portuguese and Spanish adventurers that

their activities were motivated primarily by a desire to bring the word

of God to non-Christian peoples undoubtedly included a considerable

measure of hypocrisy, there is no doubt that religious motives played a

major part in the European Age of Exploration. Religious motives were

less evident in the activities of the non-Catholic powers that entered the

competition in the seventeenth century. English and Dutch merchants

and officials were more inclined to be motivated purely by the pursuit

of economic profit.

Conditions in many areas of Asia were less conducive to these

economic and political developments. In China, a centralized monar-

chy continued to rely on a prosperous agricultural sector as the eco-

nomic foundation of the empire. In Japan, power was centralized

under the powerful Tokugawa shogunate, and the era of peace and

stability that ensued saw an increase in manufacturing and commercial

activity. But Japanese elites, after initially expressing interest in the

outside world, abruptly shut the door on European trade and ideas in

an effort to protect the ‘‘land of the gods’’ from external contamination.

In India and the Middle East, commerce and manufacturing had

played a vital role in the life of societies since the emergence of the

Indian Ocean trade network in the first centuries

C.E. But beginning in

the eleventh century, the area had suffered through an extended period

of political instability, marked by invasions by nomadic peoples from

Central Asia. The violence of the period and the local rulers’ lack of

experience in promoting maritime commerce had a severe depressing

effect on urban manufacturing and commerce.

In the early modern era, then, Europe was best placed to take

advantage of the technological innovations that had become incr easingly

available. It possessed the political stability, the capital, and the ‘‘mod-

ernizing elite’’ that spurred efforts to wrest the greatest benefit from the

new conditions. Whereas other regions were beset by internal obstacles or

had deliberately turned in ward to seek their destin y, Europe now turned

outward to seek a new and dominant position in the world. Nevertheless,

significant changes were taking place in other parts of the world as well,

and man y of these changes had relatively little to do with the situation in

the West. As we shall see, the impact of Eur opean expansion on the rest

of the world was still limited at the end of the eighteenth century . W hile

Eur opean political authority was firmly established in a few key a reas,

such as the Spice Islands and Latin America, traditional societies r e-

mained relatively intact in most regions of Africa and Asia. And processes

at work in these societies were often operating independently of events in

Europe and would later give birth to forces that acted to restrict or shape

the Western impact. One of these forces was the progressive emergence of

centralized states, some of them built on the concept of ethnic unity .

c The Art Archive

THE EMERGENCE OF NEW WORLD PATTERNS (1500--180 0) 333