Dye Dale, O`neill Robert. The road to victory: From Pearl Harbor to Okinawa

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

O

N THE EVENING OF

December 8,1941,1 sat huddled

with my parents in front of our

radio, listening to the first reports coming in of

the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. I was five

at the time but the impact of the news was so

great that I can still recall it clearly. Although

we were in Melbourne, Australia, and a long

way from the scene of the American disaster,

there were only meagre British, Dutch, and

Australian forces between ourselves and the

oncoming Imperial Japanese forces. Two days

later we were shaken by news of the sinking

off the coast of Malaya of the only British

capital ships in regional waters, the Prince of

Wales and the Repulse. We began building air

raid shelters in our back-gardens and thinking

about evacuation to the countryside. My father

patrolled the streets at night as an Air Raid

Precautions warden, enforcing the blackout

of house and external lighting to deny any

Japanese bombers an aiming mark.

How had this disaster for the United States

and its friends and Allies happened in so short

a time? Could the advance of the Japanese

armed forces be halted? What would it take to

hurl them back onto their home soil and force

them to surrender? This very timely volume

offers in depth answers to the second and third

of these questions, but let me address some

thoughts by way of reply to the first, with

gratitude to my paternal grandfather who

fought against the Boxer Rebellion in China,

1900-01, and in World War I, on each occasion

with Japanese as allies. He had 40 years of

naval experience between 1888 and 1928, and

was a keen observer of strategic matters in

the Pacific. In turn, he helped to develop my

interest in these issues while I was in my teens.

Japan discovered the potential of modern

seapower in the 1880s and through British

naval tutelage and the purchase of British

warships, it soon had a powerful fleet led by

competent officers. The Japanese sank the

Chinese Navy in two major battles of 1894

(the Yalu River) and 1895 (Wei Haiwei), and

proved themselves as the top naval power of

north-east Asia. Japan had been fostering the

expertise of the remarkable man who was to

be known as "the Nelson of the East," Admiral

Heihachiro Togo, by sending him to Britain for

seven years of training and experience. In 1902

the British went so far as to conclude a formal

alliance with Japan - which was particularly

helpful for Britain, Australia, and New

Zealand in resisting German pressures during

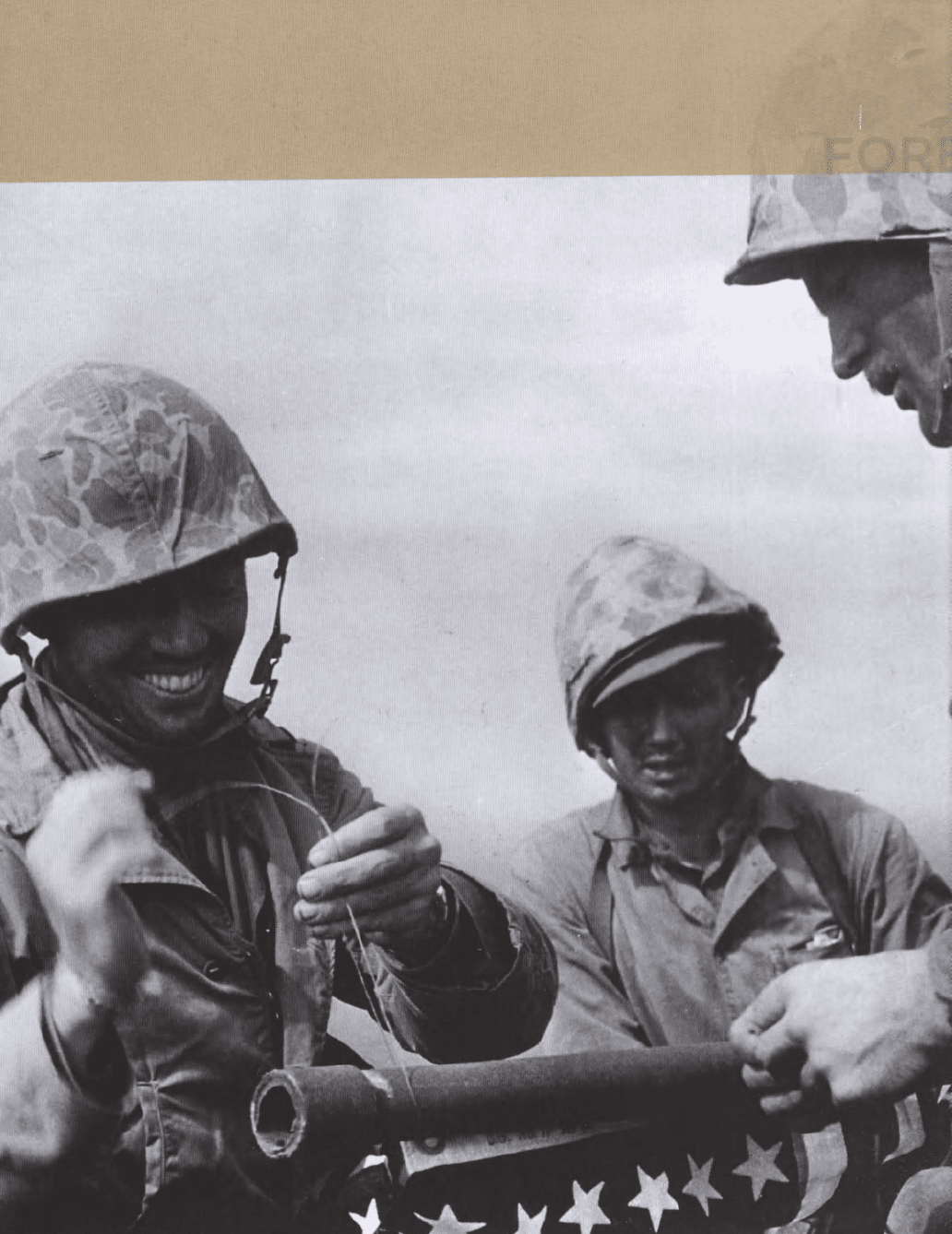

OPPOSITE

Marines on Mount

Suribachi, Iwo Jima,

wiring the US flag onto

a pole for the first flag

raising at that site.

It was later deemed

"not impressive

enough"and they

found a better, larger

flag and flag pole and

that became the most

famous picture to come

out of the Pacific.

(Tom Laemlein)

12 • THE ROAD TO VICTORY: From Pearl Harbor to Okinawa

World War I. The combination of even more

powerful British-made warships and Togo's

leadership enabled the Japanese to defeat the

strong fleet that Russia sent to the Far East at

the battle of Tsushima in 1905. As a result,

Japan was fully established as a major Pacific

naval power.

It took remarkably little time for the

Japanese to develop naval airpower. In

September 1914 they made the first successful

attack by naval aircraft in the history of warfare

when they struck the Germans in the battle of

Tsingtao, China. Having removed the German

Navy from western Pacific waters, the only

potential rival that the bold, thrusting Japanese

naval leadership then faced was the United

States Navy. The Americans had been keeping

a close eye on the Japanese since their victory

over the Russians in 1905, and in 1906 the US

moved ahead to develop a war plan to defeat

any future Japanese naval threat to US interests

in the Pacific. American authorities formally

adopted the final version of this plan, Plan

Orange, in 1924, although it had its origins in

the thinking of Rear Admiral Raymond P.

Rodgers from as early as 1911. It assumed that,

in the event of hostilities, the initial Japanese

pressure would be applied to the Philippines

and the small Pacific island bases of the US.

The American response, after a period of

mobilization and force concentration, would

be to re-take their own island bases, and

remove the Japanese from theirs, while US

naval forces were en route to relieve the

Philippines. The US fleet would then confront

the Imperial Japanese Navy in a fight to the

finish. Japan was then to be brought to her

knees by a naval blockade.

The Japanese, for their part, correctly

assessed the nature of the US war plan and

made their own which would allow a US fleet

to reach the Philippines, while suffering losses

from Japanese naval air and submarine

attacks along the way. This weakened fleet

would then be annihilated by the Japanese in

a great naval battle, similar to the one that the

US Plan Orange envisaged.

The development of the striking power of

the respective fleets in the 1920s and 30s was

thus crucial to the course of the war in

the Pacific. Another factor strengthening the

Japanese hand was its acquisition of mandates

from the League of Nations to govern the

former German islands of the northern and

central Pacific: the Carolines, the Marianas,

and the Marshalls. These mandates placed the

islands virtually under Japanese law but, like

all mandate holders, they were not permitted

to fortify them. Nonetheless, that is what the

Japanese did, creating a strategic barrier

through which US forces intending to relieve

the Philippines in a future war would have to

fight their way.

The Japanese became the object of US

diplomatic pressure soon after World War I.

The Americans wanted to end the Anglo-

Japanese alliance and to constrain the further

growth of Japanese naval power. Both

objectives were secured at the Washington

Naval Conference of 1921-22. The Japanese

were both humiliated and angry at this

outcome, and this in turn fed the tensions

that caused the war in the Pacific. Severe

limitations on Japanese migration to the US,

pressure to withdraw from former German

territory in China, and trade restrictions

aggravated the Japanese further during the

1920s and 30s. All of this played into the

hands of military and political leaders who

wanted to exploit Japan's naval strength in the

Pacific to create a new international order

there and in China.

Introduction

In the meantime both the US and Japan

had gone ahead with the planning and

development of through-deck aircraft carriers,

so that by the 1930s both navies had formidable

airpower capabilities. Despite their differences

and enmity, the Japanese and the Americans

made sporadic efforts to settle their

differences peacefully. These initiatives

proved unsuccessful and the Japanese finally

decided in 1941 to use force. In turn, the British,

having alienated the Japanese by commencing

construction of a great naval base at Singapore,

had scaled down their presence, and were

no longer a great naval power in the Pacific.

By 1941 Britain had little power to spare as it

was heavily engaged in action in Europe, North

Africa, and the Middle East. When the Japanese

decided to strike they had only the United

States to focus on, enabling the execution of the

bold and complex plan for striking the US Navy

in its base at Pearl Harbor.

This book examines the complex series of

events leading up to the attack of December 7,

1941, the attack itself, and the bloody

consequences which were to follow. I invite

the reader to study and evaluate the expert

views set forth in the following chapters, and

to think about the question of whether so great

a catastrophe could befall a major power in the

Pacific in the 21st century.

Professor Robert O'Neill

June 2011

ORIGINS OF THE

CAMPAIGN

Below, thick fluffy clouds blanketed the blue sky.

Shoving the stick forward, Lieutenant Mitsuo

Matsuzaki dropped his Nakajima B5N2 Type 97

"Kate" into more blue sky, the horizon broken by

the low land mass he was approaching. His

observer, Commander Mitsuo Fuchida, the

mission commander, was watchful. Hawaii

looked green and oddly peaceful. He scanned

the horizon. It looked too good to be true; other

than his fliers, no aircraft were visible.

It was 0730hrs Hawaii time; the date,

December 7,1941. Fuchida's destination was the

home of

the

US Pacific Fleet - Pearl Harbor. The

fleet and three aircraft carriers berthed there

were the key targets. A statement notifying the

US that war had been declared had been

scheduled for delivery to Washington an hour

earlier. This air strike would be the first act of war

between Imperial Japan and the United States.

OPPOSING

COMMANDERS

THE US COMMANDERS

Admiral Husband (Hubby) E. Kimmel was the

naval commander at Pearl Harbor. In February,

1941, he was promoted to Commander-in-Chief

Pacific (CINCPAC), becoming the navy's senior

admiral. As CINCPAC, Kimmel moved to

Pearl Harbor, home of the Pacific Fleet. He was

unhappy with the defense arrangements

in Hawaii and Pearl Harbor. At the time

responsibility for them was split: the Army was

responsible for land and air defense and the

Navy for the Navy Yard itself. The Navy was

responsible for reconnaissance but the Army

controlled the radar stations and both air and

shore defenses in case of invasion. In addition,

each service had to compete for allocation of

supplies and material. Kimmel let his strong

feelings about this tangled web of responsibilities

be known. Still, he was a career officer, and

having stated his objections, he followed orders.

Lieutenant-General Walter C. Short was the

Army commander at Pearl Harbor. His men

were well drilled but, under his command,

unit commanders carefully watched the use

of expendable ammunition and materiel.

Short followed his orders to the letter, but

failed to read between the lines and was

surprised when the Japanese attacked Pearl

Harbor. Ten days after the attack, he was

recalled to Washington and replaced by

General Delos Emmons.

Admiral Harold (Betty) R. Stark became

Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) in 1939 and

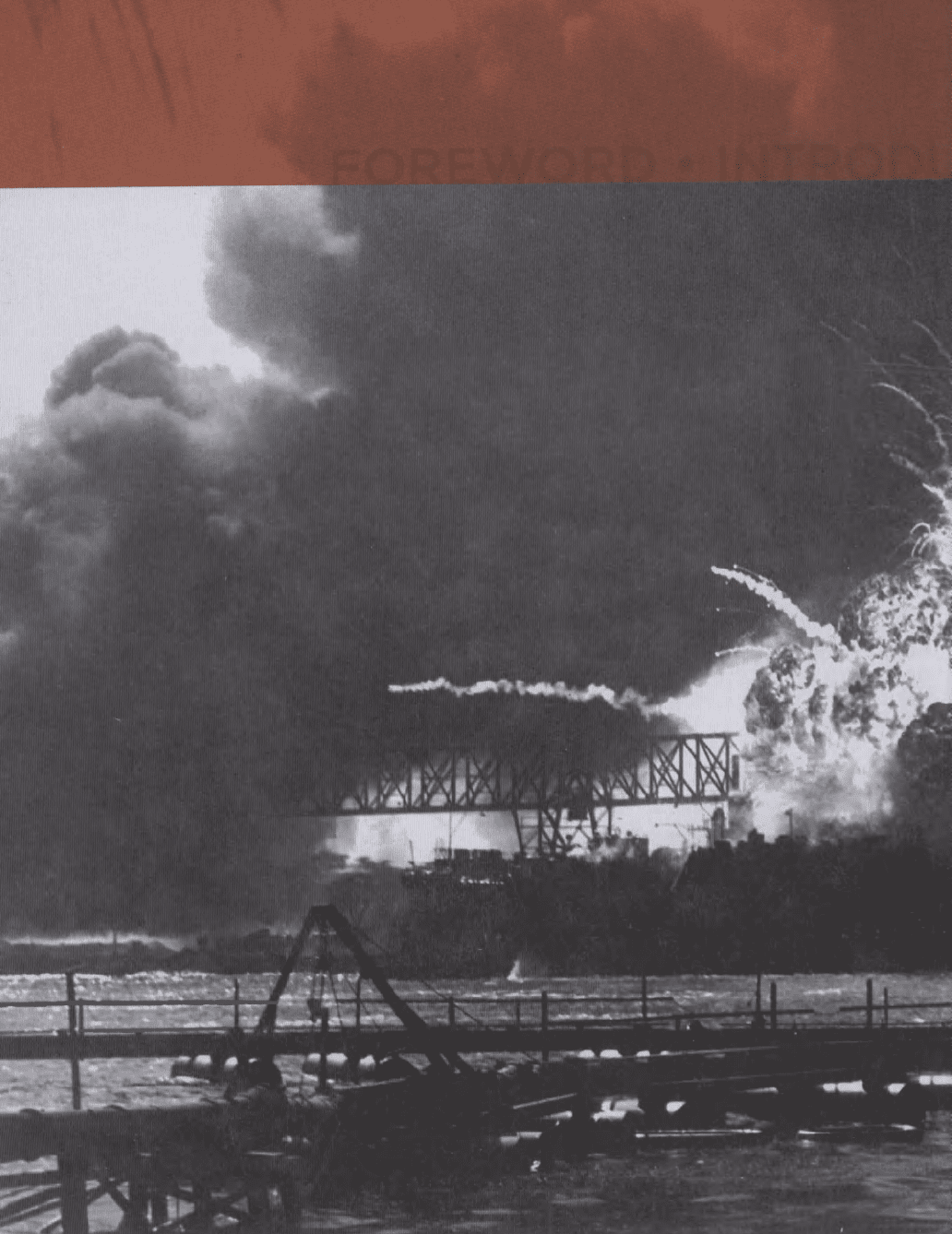

OPPOSITE

The magazine of USS

Shaw exploded after

being attacked on

Decmber 7,1941.

(US Navy/Topfoto)

16 • THE ROAD TO VICTORY: From Pearl Harbor to Okinawa

THE JAPANESE COMMANDERS

As a mere captain Isoroku Yamamoto had

successfully negotiated an increase in Japan's

naval allowance at the London Naval

Conference in 1923. He returned to Japan a

diplomatic hero and became Vice-Minister of

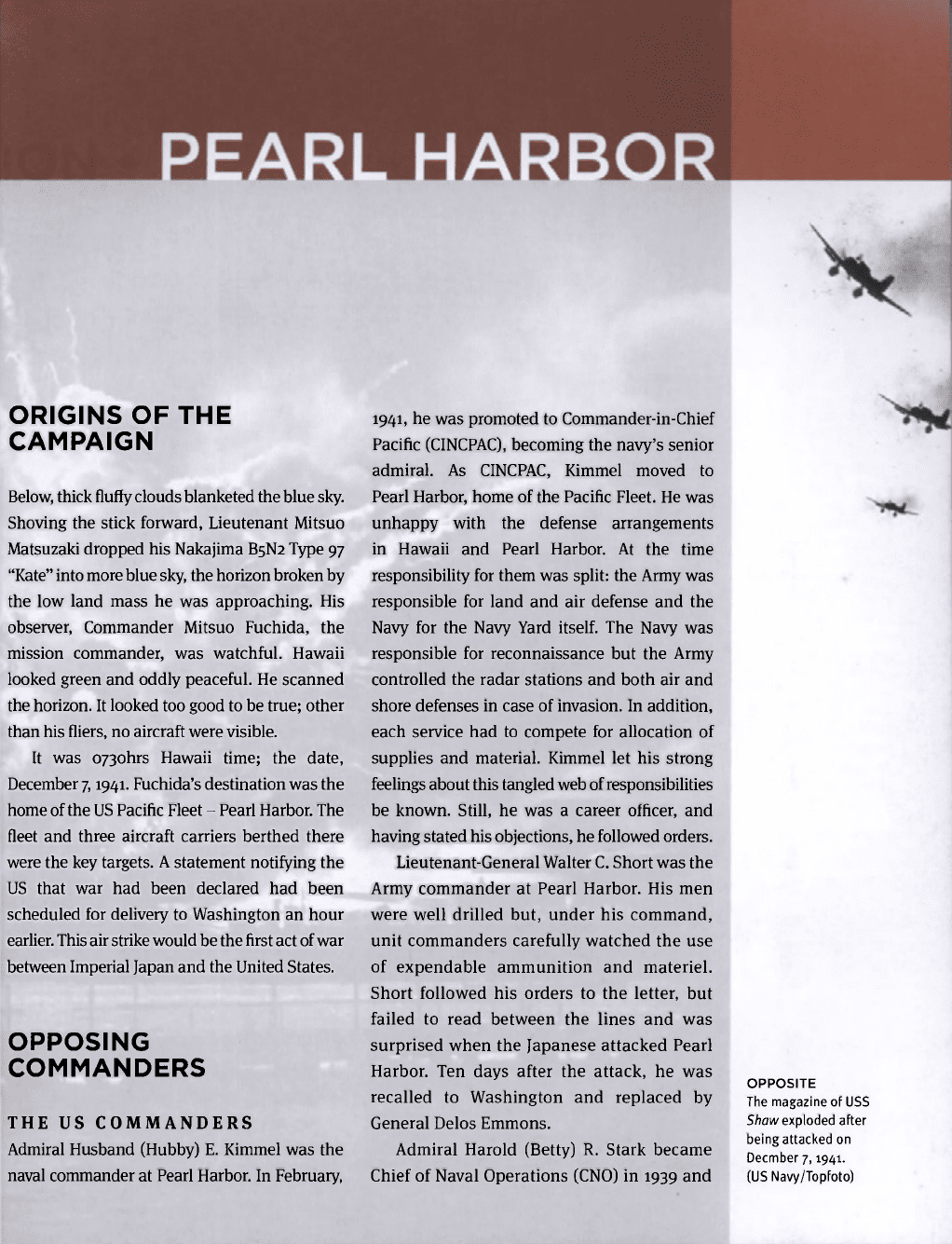

Admiral Kimmel (center)

photographed with his

operations officer

Captain Delaney (left)

and his assistant chief

of staff Captain Smith

(right). Although

aggressive and

vigilant, Kimmel

shared responsibility

for Pearl Harbor with

Lieutenant-General

Short. Both were

surprised by the

audacious Japanese

thrust at an island

almost everyone

thought too well

defended to be a

target. (US Navy)

"Yesterday, December 7, 1941 - a date which will live in

infamy - the United States of America was suddenly

and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the

Empire of Japan... As Commander-in-Chief of the Army

and Navy, I have directed that all measures be taken for

our defense... With confidence in our armed forces -

with the unbounded determination of our people - we

will gain the inevitable triumph - so help us God."

- PRESIDENT F. D. ROOSEVELT, DECEMBER 8, 1941

overcame strong isolationist sentiment to start

construction of modern naval vessels and

bases. He beefed up the Pacific Fleet at Pearl,

and, aided by information from the MAGIC

code, knew that Japanese-American relations

were dramatically declining and approaching

a state of

war.

He gave commanders warnings,

but because of the prevailing belief that Pearl

Harbor was so strong, he felt the Japanese

would attack elsewhere. When Ambassador

Nomura's message declaring war was

translated by MAGIC on December 7,1941, he

started to send a message to Pearl Harbor, but

General George C. Marshall assured him that

Army communications could get it there just

as fast. In fact, it arrived after the air raid had

begun. Stark was relieved as CNO on March 7,

1942, although Marshall retained his position.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed

General George C. Marshall as Chief of Staff on

September 1, 1939, and gave him his fourth

star. Despite his position, unlike many others,

no stigma for the debacle was attached to him.

Marshall fully supported the "defeat Germany

first" concept, and many would later blame

the length of the Pacific War on his cautious

approach to planning and implementation of

war plans.

the Navy. Yamamoto favored air power, and he

relegated the steel navy to a secondary position,

opposing the building of the battleships

Yamato and Musashi as antiquated technology,

stating: "These ... will be as useful ... as a

samurai sword." He championed new aircraft

carriers and acknowledged that he had no

confidence whatsoever in Japan's ability to win

a protracted naval war.

In mid-August, 1939, he was promoted to

full admiral and became Commander-in-Chief

of the Combined Fleet. He became a Rommel-

like figure to the men of his command, inspiring

them to greater efforts by his confidence,

and improved the combat readiness and

seaworthiness of the Imperial Japanese Navy

(IJN) by making it practice in good and bad

weather, day and night. Yamamoto did not

wish to go to war with the US, but once the

government had decided, he devoted himself

to

the task of giving Japan the decisive edge. It was

he who decided that Pearl Harbor would be

won with air power, not battleships, and the

final attack plan was his.

Commander Mitsuo Fuchida entered the

Naval Academy and befriended Commander

Minoru Genda when they discovered a shared

love for flying. Their friendship and mutual

respect was to last for years, and in many ways

it helped shape the concept of air war and the

attack on Pearl Harbor. While in China,

Fuchida learned the art of torpedo bombing,

and he was recognized throughout the IJN as a

torpedo ace.

Rear-Admiral Takijiro Onishi had

Commander Minoru Genda write a feasibility

study for a proposed Japanese attack on Pearl

Harbor. Commander Genda wrote the study

and constructed a strategy with ten main

points, most of which were incorporated into

the final plan. He developed the First Air

Group's torpedo program, and proposed a

second attack on Pearl Harbor several days

after the first, wanting to annihilate the

US fleet. He remained aboard the carrier

Akagi as Vice-Admiral Chuichi Nagumo's air

advisor, and was on deck to welcome

Fuchida's flight back.

18 • THE ROAD TO VICTORY: From Pearl Harbor to Okinawa

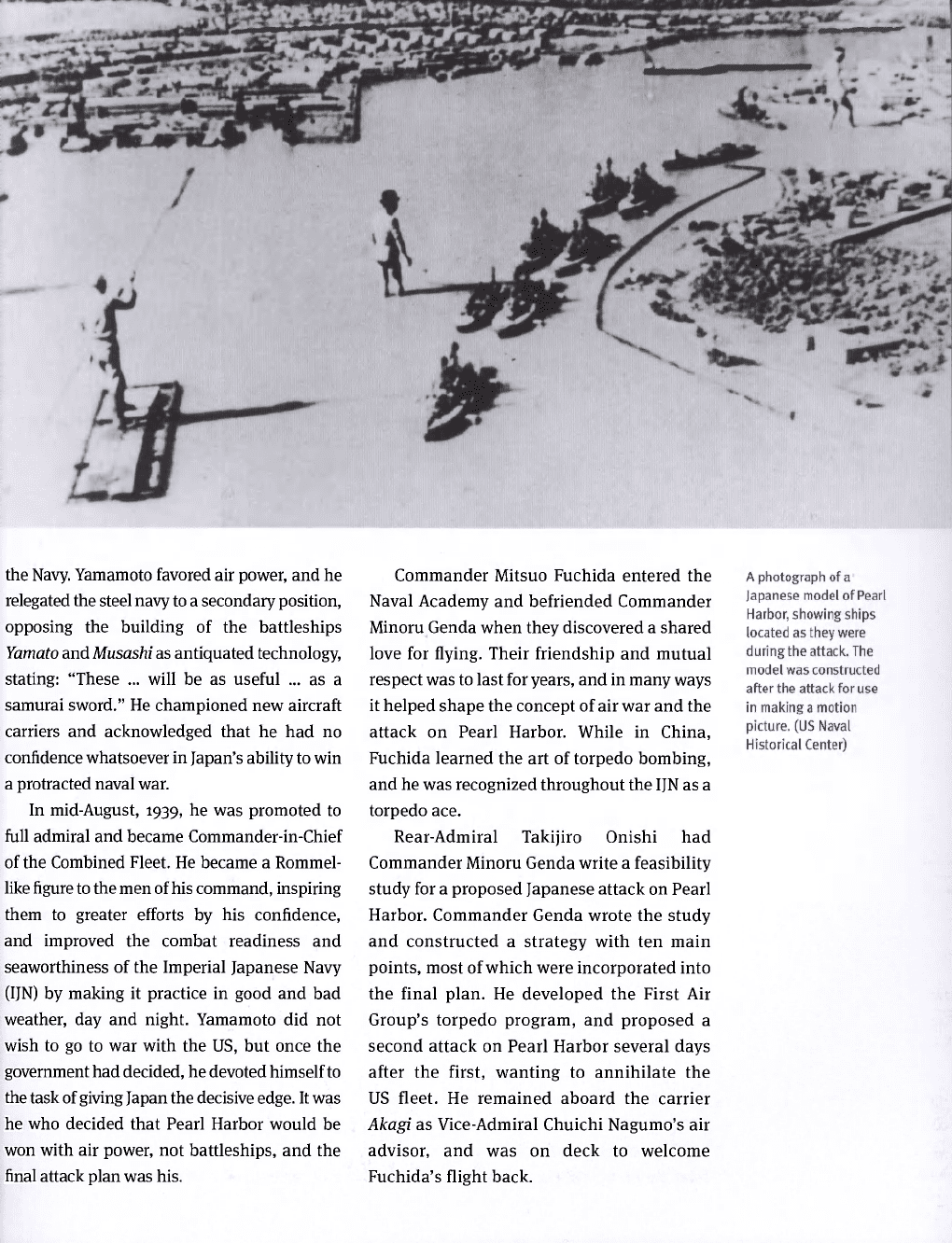

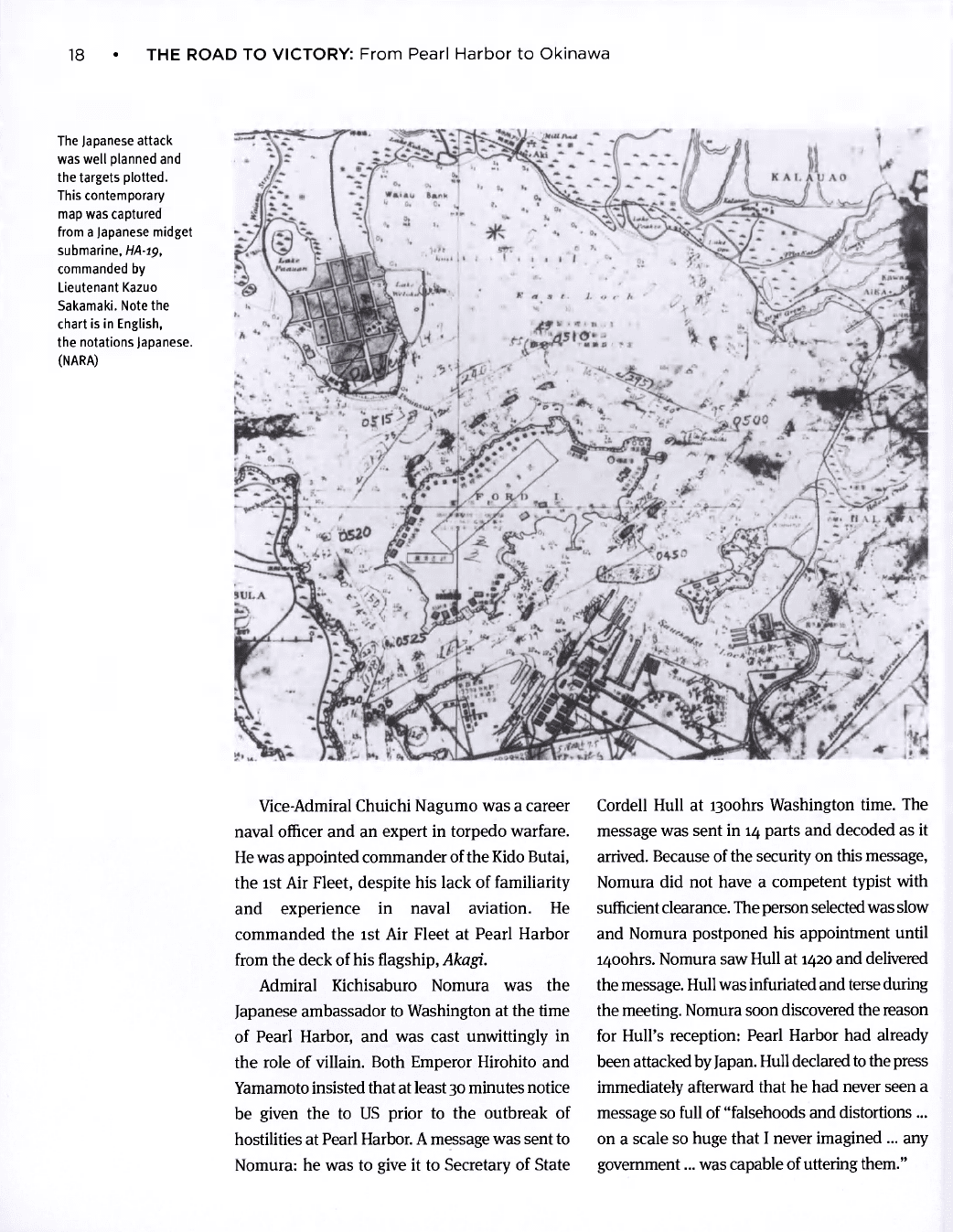

The Japanese attack

was well planned and

the targets plotted.

This contemporary

map was captured

from a (apanese midget

submarine, HA-ig,

commanded by

Lieutenant Kazuo

Sakamaki. Note the

chart is in English,

the notations )apanese.

(NARA)

Vice-Admiral Chuichi Nagumo was a career

naval officer and an expert in torpedo warfare.

He was appointed commander of the Kido Butai,

the ist Air Fleet, despite his lack of familiarity

and experience in naval aviation. He

commanded the ist Air Fleet at Pearl Harbor

from the deck of his flagship, Akagi.

Admiral Kichisaburo Nomura was the

Japanese ambassador to Washington at the time

of Pearl Harbor, and was cast unwittingly in

the role of villain. Both Emperor Hirohito and

Yamamoto insisted that at least 30 minutes notice

be given the to US prior to the outbreak of

hostilities at Pearl Harbor. A message was sent to

Nomura: he was to give it to Secretary of State

Cordell Hull at yoohrs Washington time. The

message was sent in 14 parts and decoded as it

arrived. Because of the security on this message,

Nomura did not have a competent typist with

sufficient

clearance. The person selected was slow

and Nomura postponed his appointment until

lzjoohrs. Nomura saw Hull at 1420 and delivered

the message. Hull was infuriated and terse during

the meeting. Nomura soon discovered the reason

for Hull's reception: Pearl Harbor had already

been attacked by Japan. Hull declared

to

the press

immediately afterward that he had never seen a

message so full of "falsehoods and distortions ...

on a scale so huge that I never imagined ... any

government... was capable of uttering them."