Environmental Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Weather modification

Cities, with their clustered buildings and canyons of

thoroughfares, absorb infrared heat and inadvertently modify

weather because their shape alters the flow of winds. Because

they are localized islands of heat, cities increase cloudiness.

Aerosols, or microscopic dust particles, given off in industrial

smoke

, bond with water vapor and create city

haze

and

smog

. When the aerosols contain

sulfur dioxide

and

nitro-

gen oxides

, they cause

acid rain

. Increased urban traffic

raises levels of

carbon monoxide

and

carbon dioxide

.In

the sky, jet trails contribute to the formation of clouds.

Fossil fuels

, which are ancient organic matter, release

CO

2

when they are burned. This collects in the greenhouse

band, a protective shield that circles the earth. Naturally

composed of CO

2

,

methane

, chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs),

nitrous oxide

, and water vapor, the greenhouse layer pro-

cesses infrared heat sent back into space by earth and regu-

lates the temperature of the earth. When it is too full to

allow infrared heat from earth to pass through into space,

the temperature rises on earth, affecting local, regional, and

global weather.

Intentional weather modification involves taking ad-

vantage of the energy contained within weather systems and

turning it toward a specific goal. To “make” rain, a scientist

mimics the natural process by introducing extra water drop-

lets or ice crystals in clouds. However, he needs the right

cloud shapes with the right internal temperature and the

right winds, headed in the direction of his target.

Rainmaking became a serious science in 1950 when

physicist Bernard Vonnegut at General Electric devised a

way to vaporize silver iodide to let it rise on heated air

currents into clouds where it solidified and bonded onto

water droplets to create ice crystals. Previous attempts at

rainmaking involved dropping dry ice (solid CO

2

) onto

clouds from planes, but this was expensive. Vonnegut chose

silver iodide because its molecular structure most closely

matches that of ice crystals.

In California, where the Southern California Edison

Company regularly sends out planes to seed rain clouds over

the dry San Joaquin Valley farmland, silver iodide is shot

from rockets mounted on the leading edge of the wings. It is

also vaporized into clouds from ground generators at higher

altitudes in the Sierra Mountains. In rainmaking projects,

the purpose is to avoid droughts, increase food productivity,

and augment water supplies for drinking or hydroelectric

plants. But gathering accurate data on successful seeding

and subsequent precipitation has been difficult. Currently,

most scientists agree with a longterm analysis that seasonal

cloud seeding has increased precipitation by at least 10%,

possibly as much as 20%. Clouds, which are ever-moving

collections of water vapor, regulators of heat, and generators

of tremendous internal winds, remain mysterious. Yet they

are major players in earth’s climate.

1497

Other weather modification projects include dissipat-

ing cold fogs, done routinely at major airports around the

world. In the former Soviet Union, damaging hailstorms

were successfully broken up to protect ripening crops. How-

ever,

statistics

from attempts at hail suppression in the

United States have been inconclusive, and research is ongo-

ing. In the 1950s and 1960s, scientists experimented with

seeding hurricanes to diminish the storms’ severity and alter

their path. Similarly, attempts were made to “explode” torna-

does by firing artillery into the oncoming storms. In both

cases, natural energies far exceeded any attempts at control.

“We don’t have the capability to turn the weather

around,” said Bill Blackmore of

National Oceanic and

Atmospheric Administration

(NOAA)’s Weather Modifi-

cation Reporting Program. “If we could modify the weather

a hundred percent then we could predict the weather a

hundred percent. What we need is a lot more understanding

of its complexity.”

NOAA funds the Federal State Coop Program, a six-

state research group. The Atmospheric Modification Pro-

gram at NOAA’s Wave Propagation Lab in Boulder, Colo-

rado, coordinates and evaluates state projects. Research there

and at the Institute for Atmospheric Science at the South

Dakota School of Mines and Technology involves doing

remote sensing of clouds, computer modelling of clouds, and

releasing tracers in convective clouds to better understand the

dynamics of thunderstorms.

A new way of collecting rainwater is cloud “milking.”

Researchers have been collecting fog on the mountains of

Chile by stringing 50 nylon mesh nets—39 ft (11.8 m) long

by 13 ft (4 m) wide—at regular intervals on the mountain-

side. As the windblown fogs hit the net, they trap water

particles. These are then collected into containers. On aver-

age, the system “milks” 2,500 gal (9,475 L) of drinking water

a day.

Most rainmaking activities in the United States take

place in the western states and are sponsored by water depart-

ments or districts and conducted by private and commercial

companies. The mistakes made earlier in the history of alter-

ing the weather have been dealt with by regulations in each

state. Internationally, the World Meteorological Organiza-

tion (WMO) oversees weather modification, and the Treaty

of War and Environmental Weather, signed at the Geneva

Arms Limitation Talks in 1977, forbids uncontrolled mili-

tary weather modification.

In 1971, the United States created Public Law 92-

205, which requires states to file all weather modification

activity with the NOAA’s Weather Modification Reporting

Program. Typically, about a dozen states file annually.

Two private organizations, the American Meteorolog-

ical Society in Boston, Massachusetts, and the Weather

Modification Association of Fresno, California, keep records

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Weathering

on weather modification. The Journal of Weather Modifica-

tion is an annual publication of the Institute for Atmospheric

Science at the South Dakota School of Mines and Technol-

ogy. See also Deforestation; Greenhouse effect; Ozone;

Ozone layer depletion

[Stephanie Ocko]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Arnett, D. S. Weather Modification by Cloud Seeding. New York, Academic

Press, 1980.

Breuer, G. Weather Modification: Prospects and Problems. New York: Cam-

bridge University Press, 1979.

P

ERIODICALS

“Planned and Inadvertent Weather Modification.” Bulletin of the American

Meteorological Society (March 1992): 331–337.

Strauss, S. “To Catch a Cloud.” Technology Review (May-June 1991): 18–19.

O

THER

Blackmore, W. H. A Summary of Weather Modification Activities Reported

in the United States During 1991. Silver Spring, MD: National Oceanic

and Atmospheric Administration, 1991.

Weathering

Weathering refers to the group of physical, chemical, and

biological processes that change the physical and chemical

state of rocks and soils at and near the surface of the earth.

Weathering is primarily a result of climatic forces. Because

the effects of

climate

occur at the earth’s surface, the inten-

sity of weathering decreases with depth, with most of the

effects exhibited within the first meter of the surface. The

most important climatic force is water, as it moves in and

around rocks and

soil

.

Physical weathering is the disintegration of rock into

smaller pieces by mechanical forces concentrated along rock

fractures. Abrasion of rocks occurs when wind or water carry

particles that wear away rocks. Physical weathering due to

frost is referred to as frost shattering or frost wedging. Be-

cause water expands when it freezes, it can break rocks apart

from the inside when it seeps into cracks in a rock or soil.

The specific volume (volume/unit mass) of water increases

by 9% during freezing, which produces a stress that is greater

than the strength of most rocks. Frost action is the most

common physical weathering process, as frost is widespread

throughout the world. Frost even occurs in the tropics at

high elevations, and as a weathering force, is most effective

in coastal arctic and alpine environments, where there are

hundreds of frost (freeze-thaw) cycles per year.

Exfoliation is the breaking off of rocks in curved sheets

or slabs along joints that are parallel to the ground surface.

Exfoliation occurs when a rock expands in response to the

1498

removal of adjacent rock. Most commonly the release of

stress upon a rock occurs when overlying rock is eroded away

(i.e., when the pressure of deep burial is removed). The

rock breaks apart along expansion fractures that increase in

spacing with depth.

Another type of physical weathering is salt wedging.

Most water as it moves through the earth contains dissolved

salts; in some areas the salt content may be high, with

possible sources being seawater or chemical weathering of

marine sediments. As the saline water moves into rock frac-

tures and subsequently evaporates, salt crystals form. As the

process continues, the crystals grow until they act as a wedge

and crack and break the rocks. Salt wedging most commonly

occurs in dry landscapes where the

groundwater

is near

the surface.

Hydration is a physical process that also results in

weathering. Soil aggregates and fine-grained rocks can disin-

tegrate due to wetting and drying cycles and the expansion

and contraction associated with the cycles. Also air that is

drawn into pores under dry conditions and then trapped as

water returns to the soil or rock can cause fracturing.

Thermal weathering is another physical process. Re-

peated daily heating and cooling of rock results in expansion

during heating and contraction during cooling. Different

materials expand and contract at different rates, resulting in

stresses along mineral boundaries.

Chemical weathering of rocks or soils occurs through

chemical reactions when rocks or soils react with water,

gases, and solutions. During these chemical reactions, miner-

als are added or removed or are decomposed into other

materials such as

clay minerals

.

Carbon dioxide

, a chemical weathering agent, dis-

solves in rain and forms a weak carbonic

acid

. This weak

acid, through the process of carbonation, can dissolve rocks

such as limestone and feldspar. Carbonation of limestone

can result in the formation of karst

topography

that may

include caves, disappearing streams, springs, and

sinkholes

.

In chemical oxidation weathering, rocks are trans-

formed through reactions with oxygen dissolved in water.

Iron, often found in silicate minerals, is the most commonly

oxidized mineral element, when ferrous iron (Fe

+2)

) is oxi-

dized to ferric iron (Fe

+3

). Color changes often indicate when

oxidation has occurred, such as the “rusting” seen with the

oxidation of iron. Other readily oxidized minerals include

magnesium, sulfur,

aluminum

, and chromium.

Hydrolysis is the most common weathering process,

where mineral cations in a rock or soil mineral are replaced

by

hydrogen

(H

+

) ions. Pure water is a poor hydrogen

donor, but

carbon

dioxide dissolved in water, which pro-

duces carbonic acid, acts as a source of hydrogen ions.

Weathering products formed include clay minerals.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Wells

Biological weathering occurs when organisms aid in

the breakdown of rocks and minerals. Plants such as

lichens

and mosses produce a weak acid that dissolves geological

materials. Plant roots growing in the cracks of rocks, through

the process of root pry, can make the crack larger and may

loosen other types of materials.

[Judith L. Sims]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Ollier, Cliff, and Colin Pain. Regolith, Soils, and Landforms. New York:

John Wiley & Sons Ltd., 1996.

Rolls, David, and Will J. Bland. Weathering: An Introduction to the Basic

Principles. London: Edward Arnold, 1998.

Spickert, Diane Nelson, and Marianne D. Wallace. Earthsteps: A Rock’s

Journey Through Time. Golden, CO: Fulcrum Publishing, 2000.

WEE

see

Erosion

Wells

A well is a hydraulic structure for withdrawal of

ground-

water

from aquifers. A well field is an area containing two

or more wells. Most wells are constructed to supply water

for municipal, industrial, or agricultural use. However, wells

are also used for

remediation

of the subsurface (extraction

wells), recording water levels and pressure changes (observa-

tion wells), water-quality monitoring and protection (moni-

toring wells), artificial recharge of aquifers (injection wells),

and the disposal of liquid waste (

deep-well injection

). Vac-

uum extraction system is a new technology for removing

volatile contaminant from the unsaturated zone, in which

vapor transport is induced by withdrawing or injecting air

through wells screened in the

vadose zone

.

Well construction consists of several operations: (1)

drilling; (2) installing the casing; (3) installing a well screen

and filter pack; (4) grouting; and (5) well development.

Various well-drilling technologies have been devel-

oped because geologic conditions can range from hard rock

such as granite to soft, unconsolidated geologic formation

such as alluvial sediments.

Selection of a drilling method also depends on the

type of the well that will be installed in the borehole, such

as a water-supply well or a monitoring well. The two most

widely used drilling methods are cable-tool and rotary drill-

ing. The cable-tool percussion method is a relatively simple

drilling method developed in China more than 4,000 years

ago. Drilling rigs operate by lifting and dropping a string

of drilling tools into the borehole. The drill bit crushes and

1499

loosens rock into small fragments that form a

slurry

when

mixed with water. When the slurry has accumulated so the

drilling process is significantly slowed down, it is removed

from the borehole with a bailer. In rotary drilling, the bore-

hole is drilled by a rotating bit, and the cuttings are removed

from the borehole by continuous circulation of drilling fluid.

Boreholes are drilled much faster with this method, and at

a greater depth than with the cable-tool method. Other

drilling methods include air drilling systems, jet drilling,

earth augers, and driven wells.

Though well design depends on hydrogeologic condi-

tions and the purpose of the well, every well has two main

elements: the casing and the intake portion or screen. A

filter pack of gravel is often placed around the screen to assure

good porosity and hydraulic conductivity. After placing the

screen and the gravel filter pack, the annular space between

the casing and the borehole wall is filled with a slurry of

cement or clay. The last phase in well construction is well

development. The objective is to remove fine particles

around the screen so hydraulic efficiency is improved.

A well is fully penetrating if it is drilled to the bottom

of an

aquifer

and is constructed in such a way that it

withdraws water from the entire thickness of the aquifer.

Wells are also used for conducting tests to determine

aquifer and well characteristics. During an aquifer test, a

well is pumped at a constant

discharge

rate for a period of

time, and observation wells are used to record the changes

in hydraulic head, also known as drawdown. The radius of

influence of a pumping well is the radial distance from the

center of a well to the point where there is no lowering of

the

water table

or potentiometric surface (the edge of its

cone of depression). The collected data are then analyzed

to determine hydraulic characteristics. A pumping test with

a variable discharge is often used to determine the capacity

and the efficiency of the well. A slug test is a simple method

for estimating the hydraulic conductivity of an aquifer, a

rapid water level change is produced in a piezometer or

monitoring well, usually by introducing or withdrawing a

“slug” of water. The rise or decline in the water level with

time is monitored. The data can be analyzed to estimate

hydraulic conductivity of the aquifer.

The predominant tool for extracting vapor or contami-

nated groundwater from the subsurface is a vertical well.

Howerver, in many situations where environmental remedia-

tion is necessary, a horizontal well offers a better choice,

considering aquifer geometry, groundwater flow patterns,

and the geometry of contaminant plumes. Extraction of

contaminated groundwater is often more efficient with hori-

zontal wells; a horizontal well placed through the core of a

plume

can recover higher concentrations of contaminants

at a given flow rate than a vertical well. In other cases,

horizontal wells may be the only option, as contaminants

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Adam Werbach

are often found directly beneath buildings, landfills, and

other obstacles to remedial operations. See also Aquifer resto-

ration; Drinking-water supply; Groundwater monitoring;

Groundwater pollution; Water table; Water table draw-

down

[Milovan S. Beljin]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Campbell, M., and J. H. Lehr. Water Well Technology. New York: McGraw-

Hill, 1973.

Driscoll, F. G. Groundwater and Wells. St. Paul: Johnson Filtration Sys-

tems, 1986.

Nielsen, D. A., and A. I. Johnson. Ground Water and Vadose Zone Monitor-

ing. Philadelphia: ASTM, 1990.

Adam Werbach (1972 – )

American environmentalist

Adam Werbach was born in Tarzana, California, the second

son of a psychiatrist father and therapist mother. His strong

environmental conscience was nurtured by his parents, who

were both activists in the

Sierra Club

. Werbach became a

Sierra Club member himself at age 13 and formed the Sierra

Student Coalition (SSC) at age 19, composed of 300,000

members. He served two years on the Sierra Club’s Board

of Directors as a member of the Club’s national membership

committee and volunteer development committee. Then on

May 18, 1996, at the age of only 23, Werbach was elected

president of the Sierra Club.

It was

David Ross Brower

, 60 years older than Wer-

bach, who ran the campaign for Werbach to be elected

president by the 15-member board, which in turn is elected

by the Sierra Club membership at large. As the youngest

president ever to

lead

the Sierra Club, Werbach works

with the executive director and other staff to manage an

organization of about 600,000 members and a $44 million

annual budget. The average age of Sierra Club members is

around 47, emphasizing the fact that younger generations

are currently under-represented in the environmental fields.

One of Werbach’s goals is to recruit this younger group by

appealing to what interests them—the present and how it

will affect their personal future.

Werbach believes: “The

environment

is the primary

issue that prompts this generation, my generation, to take

social and political action. Our job is to get the word out

to them and to give them a place to act on their anxieties

and convictions. My goal is to make that place the Sierra

Club.”

As a high school student, Werbach founded and served

as the first director of the Sierra Club’s national student

1500

program, the Sierra Student Coalition, which has trained,

registered, and involved thousands of students in all states

with Sierra Club

conservation

campaigns. He also orga-

nized a conference of environmental youth leaders from 20

countries for the first World Youth Leadership Camp in 1996.

During this same year he earned a B.A. from Brown with

a double major in Political science and Modern culture and

media.

Werbach has many hobbies, including music, and has

toured the United States, Europe, and Asia, singing baritone

and playing the guitar with a men’s vocal group at Brown

University. He has also written several journal articles and

a novel entitled Whirled, and has worked on several films

concerning both natural- and socially-constructed environ-

ments. His book Act Now, Apologize Later was published in

1998 and prompted others of his generation to become

much more aware of the world around them. Werbach also

currently runs a cable access show, The Thin Green Line,

which focuses on the environment.

[Nicole Beatty]

Wet scrubber

Wet

scrubbers

are devices used to remove pollutants from

flue gases. They consist of tanks in which flue gases are

allowed to mix with liquid. If the pollutant to be removed

is soluble in water, water alone can be used as the scrubbing

agent. However, most scrubbers are used to remove

sulfur

dioxide

, which is not sufficiently soluble in water. Thus,

the liquid used in such cases is one that will chemically react

with the sulfur dioxide. A solution of sodium carbonate

is such a liquid. When sulfur dioxide reacts with sodium

carbonate, it forms sodium sulfite, which can be drawn off

at the bottom of the tank. See also Flue-gas scrubbing

Wetlands

During the last four decades, several definitions of the term

“wetland” have been offered by different sources. Today’s

legal and jurisdictional delineations were published in the

Corps of Engineers Wetlands Delineation Manual and revised

in 1989. It states that wetlands are “those areas that are

inundated or saturated by surface or ground water at a fre-

quency and duration sufficient to support, and that under

usual circumstances support a prevalence of vegetation typi-

cally adapted for life in saturated

soil

conditions.”

For an area to be a wetland, it must have certain

hydrology

, soils, and vegetation. Vegetation is dominated

by

species

tolerant of saturated soil conditions. They exhibit

a variety of adaptations that allow them to grow, compete,

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Wetlands

and reproduce in standing water or waterlogged soils lacking

oxygen. Soils are wet or have developed under permanent

or periodic saturation. The

hydrologic cycle

produces

an-

aerobic

soils, excluding a strictly upland plant community.

There are seven major types of wetlands that can be

divided into two major groups: coastal and inland. Coastal

wetlands are those that are influenced by the ebb and flow

of tides and include tidal salt marshes, tidal freshwater

marshes, and mangrove swamps. Salt marshes exist in pro-

tected coastlines in the middle to high latitudes. Plants and

animals in these areas are adapted to

salinity

, periodic

flood-

ing

, and extremes in temperature. These marshes are preva-

lent along the eastern and Gulf coasts of the United States

as well as narrow belts on the west coast and along the

Alaskan coastline.

Tidal freshwater marshes occur inland from the tidal

salt marshes and host a variety of grasses and perennial

broad-leaved plants. They are found primarily along the

middle and south Atlantic coasts and along the coasts of

Louisiana and Texas.

Mangrove swamps occur in subtropical and tropical

regions of the world. Mangrove refers to the type of salt-

tolerant trees that dominate the vegetation of this wetland.

These wetlands are only found in a few places in the United

States; the largest areas are found in the southern tip of

Florida.

Inland wetlands, which constitute the majority of wet-

lands in the United States, occur across a variety of climatic

zones. They can be divided into four types: northern

peat-

lands

, southern deep water swamps, freshwater marshes,

and riparian ecosystems.

Freshwater marshes represent a variety of different

inland wetlands. They have shallow water, peat accumula-

tion, and grow cattails, arrowheads, and different species of

grasses and sedges. Major freshwater marshes include the

Florida

Everglades

,

Great Lakes

coastal marshes, and areas

of Minnesota and the Dakotas.

Southern deepwater swamps are freshwater woody

wetlands with standing water for most of the growing season.

The most recognizable type of vegetation is cypress. They

are either fed by rainwater or occur in alluvial positions

that are annually flooded. These wetlands are found in the

southeast United States.

Northern peatlands consist of deep accumulation of

peat. Primary locations are Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michi-

gan, areas of the Northeast that have been affected by the

last

glaciation

, and some mountain and coastal bays in the

southeast. Bogs are marshes or swamps that lack contact

with local

groundwater

and are acidified by organic acids

from plants. They are noted for

nutrient

deficiency and

waterlogged conditions with vegetation adapted to conserve

nutrients in this

environment

.

1501

Riparian forested wetlands, occurring along rivers and

streams, are occasionally flooded but generally dry for a large

part of the growing season. The most common type of

wetland in the United States, they are often productive be-

cause of the periodic addition of nutrients with

sediment

deposited during floods.

Wetlands are valuable in several ways. Because of their

appearance and

biodiversity

alone, wetlands are a valuable

resource. Many types of

wildlife

, including

endangered

species

such as the

whooping crane

and the alligator,

inhabit or use wetlands. Over 50% of the 800 species of

protected migratory birds rely on wetlands. Wetlands are

valuable for

recreation

, attracting hunters of ducks and

geese. Over 95% of the fish and shellfish that are taken

commercially depend on wetland

habitat

in their life cycles.

Forest wetlands are an important source of lumber.

Other wetland vegetation, such as cattails or woody shrubs,

could someday be harvested for energy production. Peat is

used in potted plants and as a soil amendment, particularly

to grow grass sod.

Wetlands intercept and store storm waters, reducing

the peak

runoff

and slowing stream discharges, reducing

flood damage. In coastal areas, wetlands act as buffers to

reduce the energy of ocean storms before they reach more

populated areas and cause severe damage. Although most

wetlands do not, some may recharge underlying ground-

water. Wetlands can improve surface

water quality

by the

removal of nutrients and toxic materials as water runs over or

through it. Most importantly, wetlands may play a significant

role in the global cycling of

nitrogen

, sulfur,

methane

, and

carbon dioxide

.

The current movement of

conservation

has encour-

aged the “reconstruction” of wetlands that have been de-

stroyed through a no-net-loss policy. Wetlands are restored

to protect coastlines, improve water quality, and replace lost

habitat. See also Commercial fishing; Convention on the

Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals; Con-

vention on Wetlands of International Importance; Riparian

land; Soil eluviation

[James L. Anderson]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Kusler, J. A., and M. E. Kentula, eds. Wetland Creation and Restoration:

The Status of the Science. Covelo, CA: Island Press, 1990.

Mitsch, W. J., and J. G. Gorselink. Wetlands. New York: Van Norstrand

Reinhold, 1993.

Williams, M., ed. Wetlands: A Threatened Landscape. Cambridge, MA: Basil

Blackwell, 1990.

O

THER

A Citizen’s Guide to Protecting Wetlands. Washington, DC: National Wild-

life Federation, 1989.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Whale strandings

Wetlands with blue geese and snow geese. (Photograph by Judd Cooney. Phototake. Reproduced by permission.)

IUCN Environmental Law Centre staff, eds. The Legal Aspects of the Protec-

tion of Wetlands. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN—The World Conservation

Union, 1989.

Wetlands Convention

see

Convention on Wetlands of

International Importance (1971)

Whale strandings

An unusual

species

of mammals,

whales

are classified in

the order Cetacea, the same order that includes

dolphins

and porpoises. Whales are warm blooded, breathe air and

have lungs, bear live young and nurse them on milk. But

unlike other mammals, they live completely in the water.

That’s why ancient civilizations believed whales were fish

until the Greek philosopher Aristotle noted that both whales

and dolphins breathed through blowholes and delivered live

babies instead of laying eggs.

There are two suborders of whales that have evolved

differently over time. Baleen whales (suborder Mysticeti) are

1502

named after the Norse word for “grooved,” because the 10

species have large grooves or pleats on their throats and

bellies. Whales in this suborder lack teeth and feed mostly

on small fish and

plankton

. Yet even with this relatively

small-sized diet, they can grow extremely large. The blue

whale, the largest species on record, can reach lengths of

more than 100 ft (30 m) and weigh over 150 tons. Other

baleen species include the grey whales, minke whales and

humpbacks.

Toothed whales (suborder Odontocoti) are typically

smaller and faster moving species, including the orca, nar-

whal, beluga, and the smaller dolphins and porpoises. These

whales use their speed and agility to capture prey; the orca

often feeds on marine mammals and birds. The majority of

toothed whales feed mainly on fish and squid.

In order to find prey in dark or murky waters, toothed

whales depend on a sense called echolocation. In fact, whales

generally have good vision but it is limited to 45 ft (13.7

m). Their sense of hearing is more remarkable and water is

an excellent conductor of sound. Echolocation works by

bouncing signals off of objects ahead. Whales can then locate

prey and navigate through water, judging water depth and

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Whales

shoreline. Toothed whales have more refined echolocation

systems, while the echonavigation abilities of baleen whales

are believed to be more rudimentary.

Whale strandings occur when whales swim or float to

shore and cannot remove themselves. The mammals are then

stuck in the shallow water. Usually, the cause of strandings

is not known, but some causes have been identified. Whales

may come to shallow water or to shore due to starvation,

disease, injuries or other traumas, or exposure to

pollution

.

Most stranded animals are found dead or die quickly after

they are found. However, there have been cases in which

stranded whales have been successfully moved to a

rehabili-

tation

facility, treated, and then released to the wild. Sea

World facilities in Texas and Florida provide rescue and

rehabilitation for stranded whales as do other organizations

such as

Greenpeace

and the Atlantic Large Whale Disen-

tanglement Network.

In recent years, underground explosions and military

sonar tests may have caused otherwise unexplainable whale

strandings off the coasts of Greece and the Bahamas. Over

the course of two days in 1996, 12 whales beached on the

coast of Greece and eventually died. These sorts of mass

strandings are quite rare, and although the exact cause was

not identified, it was discovered that the North Atlantic

Treaty Organization (NATO) was testing an experimental

sonar system in the area around the same time. No scientific

connection could be proved, but no other physical explana-

tion for the whales’ beachings could be found.

In March 2000, 16 whales became stranded on two

beaches in the Bahamas. Necropsies (animal autopsies) were

performed on six of the seven that died and no signs of

disease,

poisoning

or malnutrition were evident. However,

the United States Navy had been performing underwater

sonar experiments nearby that emit loud blasts underwater.

An auditory specialist involved in the necropsies reported

finding hemorrhages in or around the whales’ ears. If the

whales lost their echolocation capabilities, they would not

be able to note the approaching shoreline, possibly explaining

the mass stranding.

Environmentalists and scientists struggle to explain

and lessen occurrence of whale strandings. Whales’ social

behavior is such that many species travel in strongly bonded

groups. The urge to avoid separation from one another may

be stronger than that of avoiding the fatal risk of stranding

alongside one whale that is sick or injured and seeking shal-

low water.

A variety of other causes may bring about whale

strandings. Pollution causes illnesses in whales that are un-

usual to their species and damage their nervous and immune

systems. A group of killer whales stranded off the coast of

British Columbia in the 1990s revealed the highest levels

of

mercury

ever recorded for cetaceans.

1503

Even weather patterns and water temperature can lead

to whale strandings. Unfortunately, many strandings go un-

discovered and the whales cannot be saved. What’s more,

the beached whales are usually not discovered in time for a

useful necropsy so the strandings’ cause is not determined.

African stranding coordinators have been selecting samples

from stranded whales for 50 years and have yet to identify

any particular pattern that explains the reason for the phe-

nomenon. One theory is that the continent’s sandy sloping

beach is more difficult to detect by the whales’ sonar system

than a more-defined, rocky coastline. Efforts to protect

whales from

hunting

, polluting of their waters and strand-

ings are increasing around the world.

[Teresa G. Norris]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Greenaway, T. Whales. Austin, TX: Raintree, Steck-Vaughn, 2001.

P

ERIODICALS

Milius, S. “Whales Stranded During Military Test.”Science News 153

(March 21, 1998): 184.

Thurston, H. “Poisoned Seas: The Cause of Whale Strandings?” Canadian

Geographic 115 (January-February 1995): 68.

O

RGANIZATIONS

Save the Whales, PO Box 3650, Georgetown Sta., Washington, DC USA

20007 (202) 337-2332, Fax: (202) 338-9478, Email:

awi@animalwelfare.com, http://www.awionline.org/whales/indexout.html

Great Whales Foundation, PO Box 6847, Malibu, CA USA 90264 (310)

317-0755, Fax: (310) 317-1455, Toll Free: (800) 421-WAVE, Email:

whales@elfi.com

Whales

Whales are aquatic mammals of the order Cetacea. The

term is now applied to about 80

species

of baleen whales

and “toothed” whales, which include

dolphins

, porpoises,

and non-baleen whales, as well as extinct whales. Cetaceans

range from the largest known animal, the blue whale (Balea-

noptera musculus), at a length up to 102 ft (31 m) to the

diminutive vaquita (Phoceona sinus) at 5 ft (1.5 m).

Whales evolved from land animals and have lived ex-

clusively in the aquatic

environment

for at least 50 million

years, developing fish-like bodies with no rear limbs, power-

ful tails, and blow holes for breathing through the top of

their heads. They have successfully colonized the seas from

polar regions to the tropics, occupying ecological niches from

the water’s surface to ocean floor.

Baleen whales, such the right whale (Balaena glacialis),

the blue whale, and the minke whale (Balaenoptera acutoros-

trata), differ considerably from the toothed whales in their

morphology, behavior, and feeding

ecology

. To feed, a

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Whaling

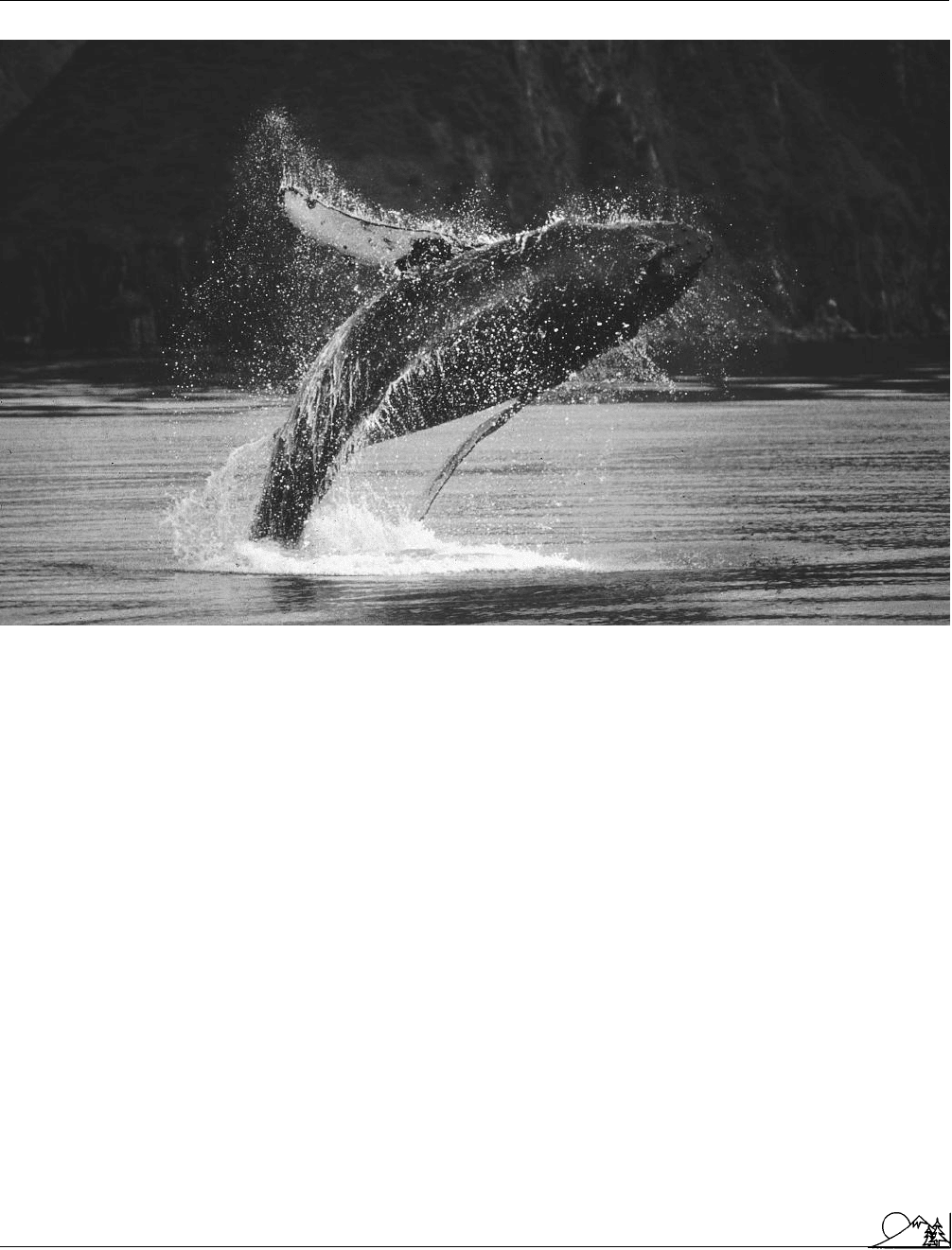

Humpback whale breaching. (Visuals Unlimited. Reproduced by permission.)

baleen whale strains seawater through baleen plates in the

roof of its mouth, capturing

plankton

and small fish. Only

the gray whale (Eschrichtius robustus) sifts ocean sediments

for bottom-dwelling invertebrates. Baleen whales migrate in

small groups and travel up to 5,000 mi (8,000 km) to winter

feeding grounds in warmer seas.

The toothed whales, such as the killer whale (Orcinus

orca) and the pilot whale (Globicephala spp.), feed on a variety

of fish, cephalopods, and other marine mammals through a

variety of active predatory methods. They travel in larger

groups that appear to be matriarchal. Some are a nuisance to

commercial fishing

because they target catches and damage

equipment.

Large whales have virtually no natural predators be-

sides humans, and nearly all baleen whales are now listed

as

endangered species

, mostly due to commercial

whal-

ing

. In the southern hemisphere, the blue whale has been

reduced from 250,000 at the beginning of the century to its

current level of a few hundred. The International Whaling

Commission (IWC), which has been setting limits on whal-

ing operations since its inception in 1946, has little power

over whaling nations, such as Japan and Norway, who con-

1504

tinue to catch hundreds of whales a year under an exemption

allowing whaling for scientific research.

[David A. Duffus]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Baker, M. L. Whales, Dolphins, and Porpoises of the World. Garden City,

NY: Doubleday, 1987.

Ellis, R. Men and Whales. New York: Knopf, 1991.

Evans, G. H. The Natural History of Whales and Dolphins. New York: Facts

on File, 1987.

U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service, Humpback Whale Recovery Team.

Final Recovery Plan for the Humpback Whale (Megaptera novaeangliae). Silver

Spring, MD: U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service, 1991.

U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service, Right Whale Recovery Team.

Final Recovery Plan for the Northern Right Whale (Eubaleana glacialis).

Silver Spring, MD: U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service, 1991.

Whaling

Although subsistence whaling by aboriginal peoples has been

carried on for thousands of years, it is mainly within about

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Whaling

A dead whale being pulled on board a whaling

vessel. (Greenpeace Photo. Reproduced by permission.)

the last thousand years that humans have pursued

whales

for commercial gain. The history of whaling may be divided

into three periods: the historical whaling era, from 1000

A.D.

to 1864-1871; the modern whaling era, from 1864-1871 to

the 1970s; and the decline of whaling, from the 1970s to

the present.

1505

The Basques of northern Spain were the earliest com-

mercial whalers. Concentrating on the capture of right

whales (Baleana glacialis), Basque whaling spread over most

of the northern Pacific Ocean as local populations dwindled

from

overhunting

. Like many whales that were later hunted

to near

extinction

, the right whale was a slow-moving and

coastal

species

.

Commercial whaling is considered to have begun when

the Basques took their whaling across the Atlantic to New-

foundland and Labrador in about 1530, where between

25,000 and 40,000 whales were taken over the next 80 years.

The search for the bowhead whale (Baleana mysticetus)in

the Arctic Ocean and the sperm whale (Physeter catadon)in

the Atlantic and Pacific provided useful whale oil, waxes,

and whalebone (actually the baleen from the whale’s upper

jaw). The oil proved to be an excellent lubricant and was

used as fuel for lighting. Waxes from body tissues made

household candles. A digestive chemical was employed as a

fixative in perfumes. Baleen served the same purposes as

many

plastics

and light metals would today, and was used

in umbrella ribs, corset stays, and buggy whips.

The first species targeted were slow swimmers that

stayed close to the coasts, making them easy prey. Whalers

used sail and oar-powered vessels and threw harpoons to

capture their prey, then dragged it back to the mainland.

As technology improved and the slow-swimming whales

began to disappear, whalers sought the larger and faster-

swimming whales.

The historical whaling period ended for several rea-

sons. At the end of the nineteenth century,

petroleum

was

discovered to be a good substitute for whale oil in lamps.

Also, the whales that were so easily caught were becoming

scarce. The technology required to take advantage of larger

and faster whales was first used by a Norwegian sealing

captain, Svend Foyn. Between 1864 and 1871, he combined

the steam-powered boat, cannon-fired harpoon, grenade-

tipped harpoon head, and a

rubber

compensator to absorb

the shock on harpoon lines to catch the whales. A steam-

powered winch brought the catch in. Although the American

whaler, Thomas Welcome Roys, was responsible for much

of the development of the rocket harpoon, it was Foyn and

the Norwegians who packaged the technology that would

dominate whaling for the next century.

Modern whaling expanded in two sequences. In the

earlier period, whaling was dominated by the spread of whal-

ing stations in the European Arctic and around Iceland,

Greenland, and Newfoundland. At the same time, it spread

on the Pacific coast of Canada and the United States, around

South Africa,

Australia

, and most significantly,

Antarctica

.

Before 1925, whaling was tied to shore processing stations

and could still be regulated from the shore. After 1925, that

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Gilbert White

system broke down as the stern-slipway floating factory was

developed, making it unnecessary for whalers to come ashore.

During the modern whaling period, many populations

were brought near extinction as no international quotas or

regulations existed. Sperm whales once numbered in the

millions, and between 1804 and 1876, United States whalers

alone killed an estimated 225,000. The gray whale (Eschrich-

tius robustus) has disappeared in the North Atlantic due to

early whaling, although Pacific populations have rebounded

significantly. The blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus), the

largest mammal on earth, was preferred by whalers for its

size after improved technology enabled them to be captured.

Though protected since 1966, the blue whale has been slow

to regain its numbers, and there may be less than 1,000 of

these creatures left in the world. Also slow to recover has

been the fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus), which was hunted

intensively after blue whales became less numerous.

As more whales were hunted and populations dimin-

ished, the need for an international regulatory agency became

apparent. The

International Convention for the Regula-

tion of Whaling

of 1946 formed the International Whaling

Commission (IWC), consisting of 38 member nations for

this purpose, but the group was largely ineffectual for about

20 years. Growing environmental and political pressure dur-

ing the 1960s and 1970s resulted in the establishment of

the New Management Procedure (NMP) that scientifically

assessed whale populations to determine safe catch limits.

In 1982 IWC decided to suspend all commercial whaling

as of 1986, to reopen in 1996, or when populations had

rebounded enough to maintain a sustained yield.

However, as of 1993, some whaling nations, Japan and

Norway in particular, threatened to leave the commission and

resume commercial whaling. Iceland has already left the asso-

ciation. Meanwhile, the IWC is looking forward to new proj-

ects, including the protection of

dolphins

and porpoises.

Today, whaling is permitted by aboriginal groups in

Canada, the United States, the Caribbean, and Siberia. Un-

regulated “pirate whalers” continue to kill and market whale

meat, and scientific whaling continues to supply meat prod-

ucts primarily to the Japanese market. At the same time,

various scientific specialty groups are working on compre-

hensive population assessments.

Because of migratory habits and the difficulty in

sighting deep ocean whales, it is difficult to accurately esti-

mate their population levels. In many cases, it is impossible

to ascertain whether or not a species is in danger. It is clear,

though, that the world’s whales cannot sustain

hunting

at

anywhere near the rates they had been harvested in the past.

See also American Cetacean Society; Environmental law;

Migration

[David A. Duffus]

1506

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Credlund, A. G. Whales and Whaling. New York: Seven Hills Books, 1983.

Tonnessen, J. N., and A. O. Johnsen. The History of Modern Whaling.

London: Hurst and Co., 1982.

P

ERIODICALS

Holy, S. J. “Whale Mining, Whale Saving.” Marine Policy (July 1985):

192–213.

M’Gonigle, R. M. “The ’Economizing’ of Ecology: Why Big, Rare Whales

Still Die.” Ecology Law Quarterly 9 (1980): 119–237.

Gilbert White (1720 – 1793)

English naturalist

Gilbert White was born in 1720 in the village of Selborne,

Hampshire, England. The eldest of eight children, he was

expected to attend college and join the priesthood. He earned

his bachelor’s degree at Oxford in 1743 and his master’s

degree in 1746. A fair student, White was well known for

his rambunctious and romantic exploits. White developed

a fuller sense of religious identity after college. He was

ordained a priest three years after leaving Oxford and was

subsequently assigned to a parish near his family home in

Hampshire, known as “The Wakes.” His religious perspec-

tive played an important role throughout the rest of his life,

and this is reflected in the beauty and gentleness of his

writings.

It was at The Wakes that White began studying

na-

ture

and recording his observations in letters and daily diary

notations, which also provide an interesting look at various

aspects of local life. He was highly susceptible to carriage

sickness and rarely traveled, and his writings therefore fo-

cused solely on his immediate environment—the gardens in

the village of Selborne. He organized his observations in

what he called his “Garden Kalendar,” and in 1789, these

notes, letters, and memos were combined to comprise The

Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne, now considered

a classic of English literature.

White’s ability to write in a clear and unpretentious

poetic style is evident throughout the book. He closely

watched leaf warblers, cuckoos, and swallows, and unlike

his contemporaries, he describes not just the anatomy and

plumage of the birds, but their habits and habitats. He was

the first to identify the harvest mouse, Britain’s smallest

mammal, and sketched its physical traits as well as noting

its behaviors. The Natural History also presents descriptive

passages of insect biology and wild flowers White found at

Selborne.