Environmental Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Yucca Mountain

focal point in the controversy of whether we are “loving our

parks to death.” People and traffic management has become

as critical as traditional resource management. At Yosemite,

balancing the public’s needs and desires with the protection

of the

natural resources

is the National Park Service’s

greatest challenge as they enter the twenty-first century.

[Ted T. Cable]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Frome, M. National Park Guide. 19th ed. Chicago: Rand McNally, 1985.

O

THER

Yosemite 1992 Fact Sheet. National Park Service, U. S. Department of

Interior, 1992.

O

RGANIZATIONS

Yosemite National Park, P.O. Box 577, Yosemite National Park, CA 20240

(209) 372-0200, Email: comments@yosemite.com, <http://

www.yosemitepark.com>

National Park Service, 1849 C Street NW, Washington, D.C. 20240

(202) 208-6843, <http://www.nps.gov>

Yucca Mountain

Yucca Mountain is a barren

desert

ridge about 90 mi (161

km) northwest of Las Vegas, Nevada. The

U.S. Department

of Energy

plans to build its first high-level nuclear waste

storage facility there in an extensive series of tunnels deep

beneath the desert surface. Choosing this site has been a

long and divisive process. Although over 20 years and more

than $7 billion have been spent designing and testing the

storage facility, scientists are still not clear whether the facil-

ity will remain dry and stable for the thousands of years it

will take for natural decay processes to make the wastes less

radioactive.

Most of the nuclear waste to be stored at Yucca Moun-

tain will come from nuclear

power plants

. As radioactive

uranium

235 is consumed in fission reactions, the fuel be-

comes depleted and accumulating waste products reduce

energy production. Every year about one-third of the fuel

in a typical reactor must be removed and replaced with a

fresh supply. The spent (depleted) fuel must be handled and

stored very carefully because it contains high concentrations

of dangerous radioactive elements, in addition to natural

uranium, thorium, and

radon

isotopes. Some of these mate-

rials have very long half-lives, requiring storage for at least

10,000 years before their

radioactivity

is reduced to harm-

less levels by natural decay processes.

Originally, the United States intended to reprocess

spent fuel to extract and purify unused uranium and

pluto-

nium

as fuel for advanced breeder reactors (a type of nuclear

reactor). Reprocessing plants released unacceptable amounts

1547

of radioactivity, however, and breeder reactors proved to be

too expensive and dangerous to serve as civilian power

sources. For a time in the 1950s, nuclear wastes were dumped

in the ocean, but that practice was stopped when it was

discovered that the corroding metal waste containers allow

radio-isotopes to dissolve in seawater.

In 1982, the U.S. Congress ordered the Department of

Energy (DOE) to build two sites for permanent

radioactive

waste

disposal on land by 1998. Understandably, no one

wanted this toxic material in their backyard. In 1987, after

a long and highly contentious process, the DOE announced

that it could only find one acceptable site: Yucca Mountain.

The storage facility would be a honeycomb of tunnels

more than 1,000 ft (303.3 m) below ground. When finished,

the total length of the tunnels would be more than 112

mi (180 km)—approximately the size of the world’s largest

subway system in New York City. Altogether, the tunnels

would have room for more than 80,000 tons of nuclear waste

packed in corrosion-resistant metal canisters. Because Yucca

Mountain is located in one of the driest areas in the United

States, and the bedrock is composed of highly stable volcanic

tuff (compacted ash), the DOE hopes that storage areas will

remain intact and free of leaks for the thousands of years it

will take for the wastes to decay to a harmless state. Total

costs for this facility have been estimated to be as high as

$58 billion for construction and the first 50 years operation.

Ever since its designation as the nation’s sole repository

for high-level nuclear waste, Yucca Mountain has been em-

broiled in both scientific and political controversy. Citizens

of Nevada feel that their state was chosen only because they

don’t have the political clout to resist. Ironically, Nevada

doesn’t have a

nuclear power

plant. State officials and the

Nevada Congressional delegation have vowed to do every-

thing in their power to try to stop construction and operation

of the nuclear waste facility.

Scientists are divided about the safety of the site. Al-

though some studies suggest that Yucca Mountain has been

geologically stable for thousands of years, others show a

history of fairly recent volcanic activity and large earthquakes

in the area. Fractures and faults have been discovered in the

bedrock that could allow ground water to seep into storage

vaults if the

climate

changes. One hydrologist suggested

that

groundwater

levels, while low now, could rise suddenly

and fill the tunnels with water. Opponents of the site claim

that over 200 technical problems had not been solved by

the DOE by 2002.

The storage project has been continually delayed. After

over $1 billion had been spent on exploratory studies and

trial drilling at Yucca Mountain, the DOE announced in

1986 that it could not meet the 1998 deadline imposed by

Congress. The earliest date by which the repository might

be operational is now 2010. States and power companies,

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Yucca Mountain

having already paid more than $12 billion to the DOE to

build the repository, have threatened to sue the government

if it does not open as originally promised. Some utilities

have begun to negotiate privately with Native American

tribes and foreign countries to take their nuclear wastes.

While underground storage of nuclear wastes is

fraught with problems and uncertainties, none of the alterna-

tives now available appears better. Currently, about 45,000

tons of spent fuel is sitting at 131 sites, including 103 op-

erating nuclear plants, in 39 states. Another 20,000 tons are

expected to be generated before a storage facility can be

opened in 2010, or about 2,000 tons of new waste per year.

Most of this waste is being stored in deep water-filled pools

inside nuclear plants. These pools were never intended for

long-term storage and are now over-crowded. Many power

plants have no more room for spent fuel storage and will be

forced to shut down by 2010 unless some form of long-term

storage is approved. In 1997, the DOE asked Congress for

$100 million to purchase large steel casks in which power

companies can stockpile spent fuel assemblies in outdoor

storage yards. Neighbors who live near these storage sites

worry about the possibility of leakage and accidents. Never-

theless, several utilities have already begun on-site

dry cask

storage

. It is estimated that 165 million Americans live

within a two-hour drive of stored high-level nuclear waste.

In February 2002, under the recommendation of En-

ergy Secretary Spencer Abraham, President George W. Bush

approved Yucca Mountain as the nation’s nuclear waste stor-

age site, to be opened in 2010. It would receive a minimum

of 3,000 tons of nuclear waste per year for 23 years, storing

up to a legal maximum of 77,000 tons. After 2007, another

energy secretary may consider expanding the storage facility.

As expected, and as allowed by federal law, the state

of Nevada filed a formal objection to the site approval. In

May 2002 the U.S. House of Representatives voted to over-

ride Nevada’s objections to the site. A major political battle

was then taken to the U.S. Senate, which had until July 26,

2002 to decide upon the future of U.S. nuclear waste dis-

posal. In July 2002 the site was approved.

The nuclear power industry is the main supporter of

the storage site, in order to continue producing nuclear en-

1548

ergy, which supplies about 20% of U.S. electricity. Oppo-

nents of the site claim that long-term storage and

transpor-

tation

of the waste is far too dangerous, given inconclusive

scientific studies. Furthermore, if nuclear power is continued,

opponents note that Yucca Mountain will eventually run

out of space and the nuclear waste problem will still be

unsolved.

Waste storage at Yucca Mountain is a complex, expen-

sive, and potentially high-risk problem that exemplifies the

complications of many environmental issues. It also demon-

strates the difficulty of making democratic decisions in issues

with consequences that affect large geographical areas and

future generations

in ways that are difficult to predict and

potentially control.

[William P. Cunningham Ph.D. and Douglas Dupler]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Gerrard, Michael B. Fairness in Toxic and Nuclear Waste Siting. Cambridge,

MA: MIT Press, 1994.

Rahm, Dianne, ed. Toxic Waste and Environmental Policy in the Twenty-

first Century United States. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2002.

Shrader-Frechette, K. S. Burying Uncertainty: Risk and the Case Against

Geological Disposal of Nuclear Waste. Berkeley: University of California

Press, 1994.

Streissguth, Thomas, ed. Nuclear and Toxic Waste. San Diego, CA:

Greenhaven Press, 2001.

P

ERIODICALS

“Battle of Yucca Mountain.” Washington Post, April 30, 2002: A18.

“How Safe is Safe?” Christian Science Monitor April 18, 2002: 14.

Kerr, R. A. “A New Way to Ask the Experts: Rating Radioactive Waste

Risks.” Science November 8, 1996: 913.

Whipple, C. G. “Can Nuclear Waste be Stored Safely at Yucca Mountain?”

Scientific American 274, no. 6: 72–77.

O

THER

Environmental Protection Agency. Yucca Mountain Standards. June 19,

2002 [cited July 4, 2002]. <http://www.epa.gov/radiation/yucca/in-

dex.html>.

O

RGANIZATIONS

U.S. Department of Energy, 1000 Independence Avenue SW, Washington,

DC 20585 (202) 586-6151, Fax: (202) 586-0956, <http://www.doe.gov>

Yucca Mountain Project, PO Box 364629, North Las Vegas, NV 89036-

8629 (800) 225-6972, Fax: (702) 295-5222, <http://www.ymp.gov>

Z

Zebra mussel

The zebra mussel (Dreissena polymorpha) is a small bivalve

mollusk native to the freshwater rivers draining the Caspian

and Black Seas of western Asia. This

species

of shellfish,

which gets its name from the dark brown stripes on its tan

shell, was introduced into the

Great Lakes

of the United

States and Canada and became established sometime be-

tween 1985 and 1988.

The zebra mussel was first discovered in North

America in June of 1988 in the waters of Lake St. Clair.

The introduction probably took place two or three years

prior to the discovery, and it is believed that a freighter

dumped its ballast water into Lake St. Clair, flushing the

zebra mussel out in the process. By 1989 this mussel had

spread west through Lake Huron into Lake Michigan and

east into

Lake Erie

. Within three years it had spread to all

five of the Great Lakes.

Unlike many of its other freshwater relatives, which

burrow into the sand or

silt

substrate of their

habitat

, the

zebra mussel attaches itself to any solid surface. This was

the initial cause for concern among environmentalists as

well as the general public; these mollusks were attaching

themselves to boats, docks, and water intake pipes. Zebra

mussels also reproduce quickly, and they can form colonies

with densities of up to 100,000 individuals per square meter.

The city of Monroe, Michigan, lost its water supply for two

days because its intake pipes were plugged by a huge colony

of zebra mussels, and Detroit Edison spent half a million

dollars cleaning them from the cooling system of its Monroe

power plant. Ford Motor Company was forced to close its

casting plant in Windsor, Ontario, in order to remove a

colony from the pipes which send cooling water to their

furnaces.

Although the sheer number of these filter feeders has

actually improved

water quality

in some areas, they still

pose threats to the ecological

stability

of the aquatic

ecosys-

tem

in this region. Zebra mussels are in direct

competition

with native mussel species for both food and oxygen. Several

1549

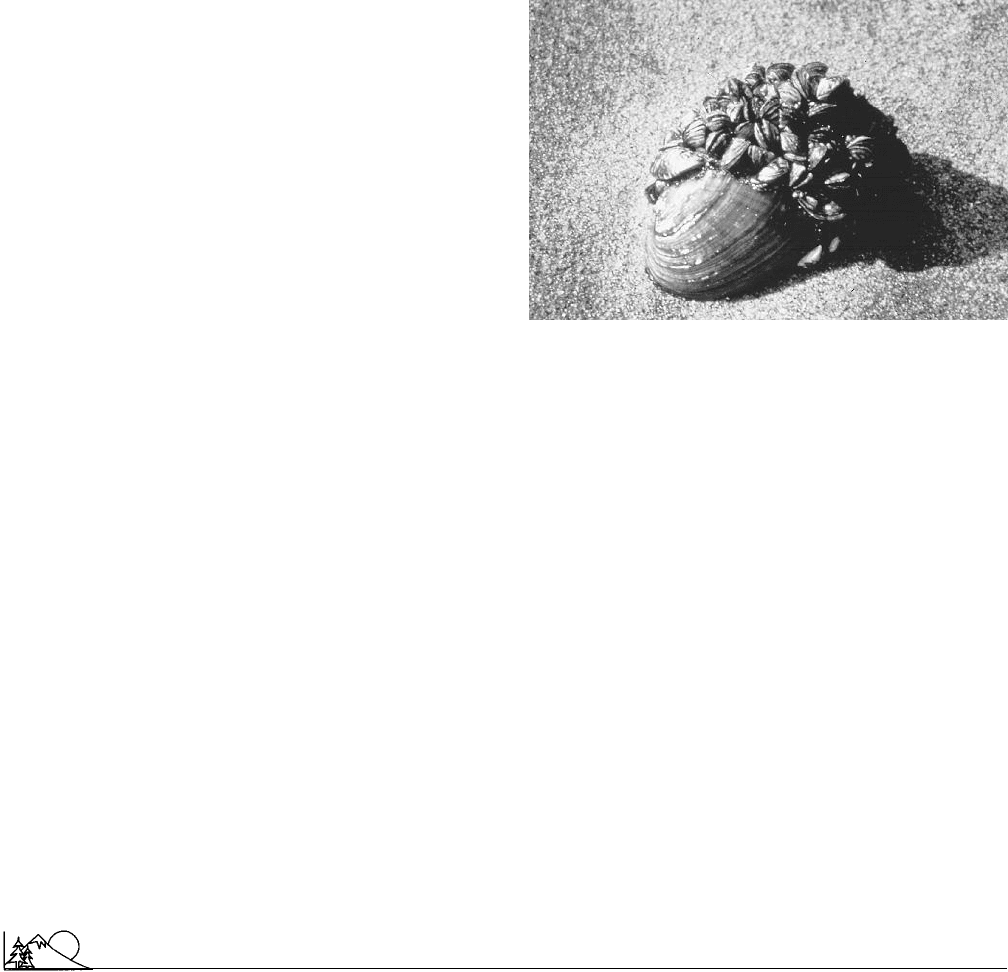

Zebra mussel. (Michigan Sea Grant Society. Repro-

duced by permission.)

colonies have become established on the spawning grounds

of commercially important species of fish, such as the wall-

eye, reducing their reproductive rate. The zebra mussel feeds

on algae, and this may also represent direct competition with

several species of fishes.

The eradication of the zebra mussel is widely consid-

ered an impossible task, and environmentalists maintain

that this species will now be a permanent member of the

Great Lakes ecosystem. Most officials in the region agree

that money would be wasted battling the zebra mussel,

and they believe that it is more reasonable to accept their

presence and concentrate on keeping intake pipes and

other structures clear of the creatures. The zebra mussel

has very few natural predators, and since it is not considered

an edible species, it has no commercial value to man.

One enterprising man from Ohio has turned some zebra

mussel shells into jewelry, but currently the supply far

exceeds the demand.

[Eugene C. Beckham]

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Zebras

R

ESOURCES

P

ERIODICALS

Griffiths, R. W., et al. “Distribution and Dispersal of the Zebra Mussel

(Dreissena polymorpha) in the Great Lakes Region.” Canadian Journal of

Fisheries and Aquatic Science 48 (1991): 1381–1388.

Holloway, M. “Musseling In.” Scientific American 267 (October 1992):

30–36.

Schloesser, D. W., and W. P. Kovalak. “Infestation of Unionids by Dreissena

polymorpha in a Power Plant Canal in Lake Erie.” Journal of Shellfish Research

10 (1991): 355–359.

Walker, T. “Dreissena Disaster.” Science News 139 (May 4, 1991): 282–284.

Zebras

Zebras are striped members of the horse family (Equidae)

native to Africa. These grazing animals stand 4–5 ft (1.2–

1.5 m) high at the shoulders and are distinctive because of

their striking white and black or dark brown stripes running

alternately throughout their bodies. These stripes actually

have important survival value for zebras, for when they are

in a herd, the stripes tend to blend together in the bright

African sunlight, making it hard for a lion or other predator

to concentrate on a single individual and bring it down.

The zebra’s best defense is flight, and it can outrun

most of its enemies. It is thus most comfortable grazing and

browsing in groups on the flat open plains and

grasslands

.

Zebras are often seen standing in circles, their tails swishing

away flies, each one facing in a different direction, alert for

lions or other predators hiding in the tall grass.

Most zebras live on the grassy plains of East Africa,

but some are found in mountainous areas. They live in small

groups led by a stallion, and mares normally give birth to a

colt every spring. Zebras are fierce fighters, and a kick can

kill or cripple predators (lions, leopards, cheetahs, jackals,

hyenas, and wild dogs). These predators usually pursue new-

born zebras, or those that are weak, sick, injured, crippled,

or very old, as those are the easiest and safest to catch and

kill. Such predation helps keep the

gene pool

strong and

healthy by eliminating the weak and diseased and ensuring

the “survival of the fittest.”

Zebras are extremely difficult to domesticate, and most

attempts to do so have failed. They are often found grazing

with wildebeest, hartebeest, and gazelle, since they all have

separate nutritional requirements and do not compete with

each other. Zebras prefer the coarse, flowering top layer of

grasses, which are high in cellulose. Their trampling and

grazing are helpful to the smaller wildebeest, who eat the

leafy middle layer of grass that is higher in protein. And the

small gazelles feed on the protein-rich young grass, shoots,

and herb blossoms found closest to the ground.

One of the most famous African

wildlife

events is

the seasonal 800-mi (1,287-km)

migration

in May and

1550

November of over a million zebras, wildebeest, and gazelles,

sweeping across the Serengeti plains, as they have done for

centuries, “in tides that flow as far as the eye can see.” But

it is now questionable how much longer such scenes will

continue to take place.

Zebras were once widespread throughout southern and

east Africa, from southern Egypt to Capetown. But

hunting

for sport, meat, and hides has greatly reduced the zebra’s

range and numbers, though it is still relatively numerous in

the parks of East Africa. One

species

, once found in South

Africa, the quagga (Equus quagga quagga) is already extinct,

wiped out by colonists in search of hides to make grain sacks.

Several other species of zebra are threatened or endan-

gered, such as Grevy’s zebra (Equus grevyi) in Kenya, Ethio-

pia, and Somalia; Hartmann’s mountain zebra (Equus zebra

hartmannae) in Angola and Namibia; and the mountain

zebra (Equus zebra zebra) in South Africa. The Cape moun-

tain zebra has adapted to life on sheer mountain slopes and

ravines where usually only wild goats and sheep can survive.

In 1964, only about 25 mountain zebra could be found in

the area, but after two decades of protection, the population

had increased to several hundred in Cradock

National Park

in the Cape Province’s Great Karroo area.

Probably the biggest long-term threat to the survival

of the zebra is the exploding human population of Africa,

which is growing so rapidly that it is crowding out the

wildlife and intruding on the continent’s parks and refuges.

Political instability and the proliferation of high powered

rifles in many countries also represent a threat to the survival

of Africa’s wildlife.

[Lewis G. Regenstein]

R

ESOURCES

P

ERIODICALS

D’Alessio, V. “Born-Again Quagga Defies Extinction.” New Scientist 132

(November 30, 1991): 14.

Grubb, P. “Equus burchelli.” Mammalian Species no. 157, 1981.

Miller, J. A. “Telling a Quagga By Its Stripes.” Science News 128 (August

3, 1985): 70.

Penzhorn, B. L. “Equus zebra.” Mammalian Species no. 314, 1988.

Zero discharge

Zero

discharge

is the goal of eliminating discharges of

pollutants by industry, government, and other agencies to

air, water, and land with a view to protect both public health

and the integrity of the

environment

. Such a goal is difficult

to achieve except where there are point sources of

pollution

,

and even then the cost of removing the last few percent of

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Zero population growth

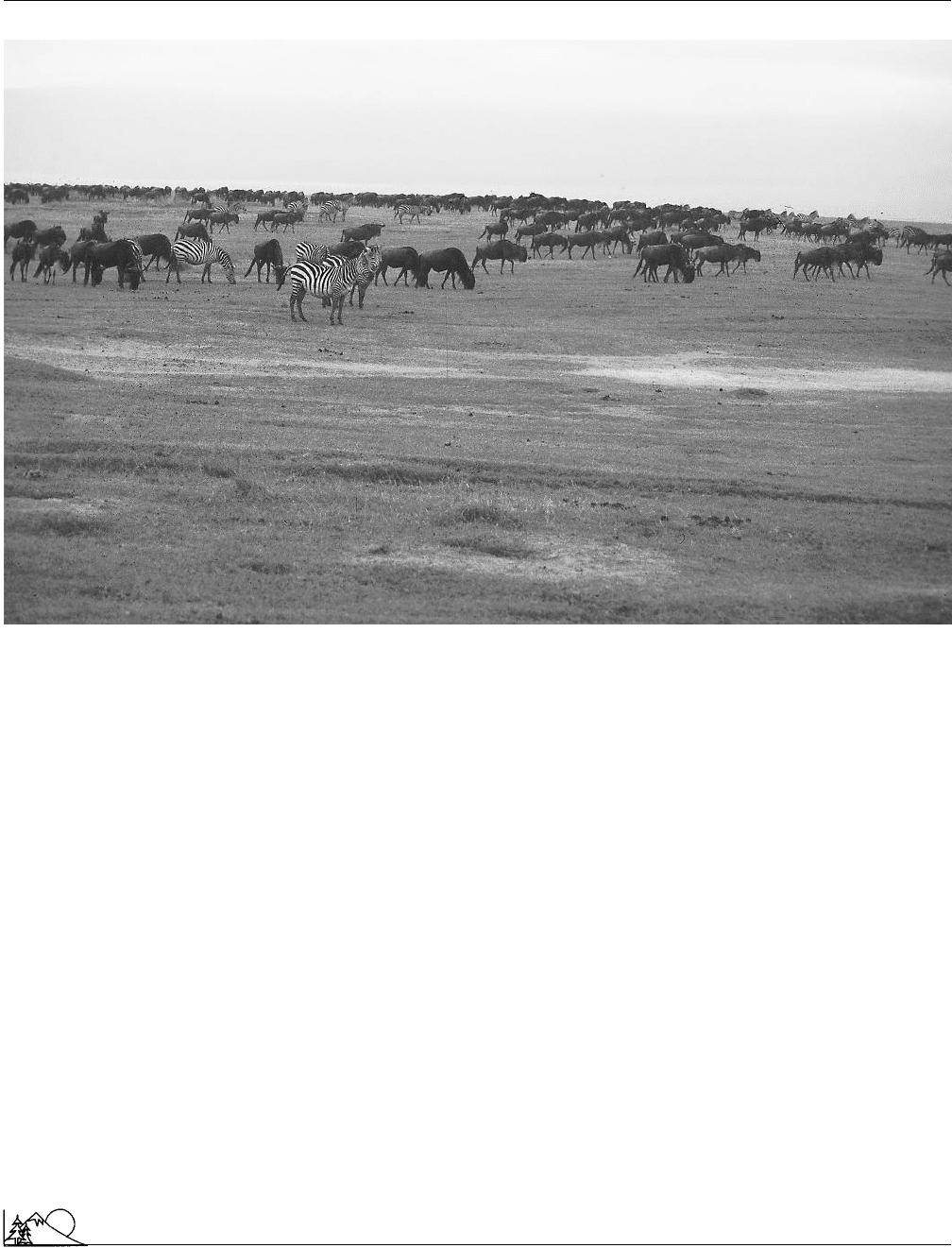

Zebras and wildebeasts at Ngorongoro Crater, Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. (Photograph by Carolina Biological

Supplies. Phototake. Reproduced by permission.)

a given pollutant may be prohibitive. However, the goal is

attainable in many specific cases (e.g., the electroplating

industry), and is particularly urgent in the case of extremely

toxic pollutants such as

plutonium

and dioxins. In other

cases, it may be desirable as a goal even though it is not

likely to be completely attained.

Zero discharge was actually proposed in the early

1970s by the United States Senate as an attainable goal for

the Federal

Water Pollution

Control Acts Amendments of

1972. However, industry, the White House, and other

branches of government lobbied intensely against it, and

the proposal did not survive the legislative process. See

also Air quality criteria; Pollution control; Water quality

standards

Zero population growth

Zero

population growth

(also called the replacement

level of fertility) refers to stabilization of a population at

its current level. A population growth rate of zero means

1551

that people are only replacing themselves, and that the

birth and death rates over several generations are in

balance. In more developed countries (MDC), where infant

mortality

rates are low, a fertility rate of about 2.2 children

per couple results in zero population growth. This rate

is slightly more than two because the extra fraction includes

infant deaths, infertile couples, and couples who choose

not to have children. In

less developed countries

(LDC),

the replacement level of fertility is often as high as six

children per couple.

Zero population growth, as a term, lends its name to

a national, non-profit organization founded in 1968 by Paul

R. Ehrlich, which works to achieve a sustainable balance

between population, resources, and the

environment

world-

wide. See also Family planning

R

ESOURCES

O

RGANIZATIONS

Zero Population Growth, 1400 16th Street NW, Suite 320, Washington,

D.C. 20036

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Zero risk

Zero risk

A concept allied to, but less stringent than, that of

zero

discharge

. Zero risk permits the release to air, water, and

land of those pollutants that have a

threshold dose

below

which public health and the

environment

remain undam-

aged. Such thresholds are often difficult to determine. They

may also involve a time element, as in the case of damage

to vegetation by

sulfur dioxide

in which less severe fumiga-

tions over a longer period are equivalent to more severe

exposures over a shorter period. See also Air quality criteria;

Pollution control; Water quality standards

Zone of saturation

In discussions of

groundwater

, a zone of saturation is an

area where water exists and will flow freely to a well, as it

does in an

aquifer

. The thickness of the zone varies from a

few feet to several hundred feet, determined by local geology,

availability of pores in the formation, and the movement of

water from recharge to points of

discharge

.

Saturation can also be a transient condition in the

soil

profile

or

vadose zone

during times of high precipitation

or

infiltration

. Such saturation can vary in duration from a

few days or weeks to several months. In soils, the saturated

zone will continue to have unsaturated conditions both above

and below it; when a device used to measure saturation,

called a piezometer, is placed in this zone, water will enter

and rise to the depth of saturation. During these periods,

the

soil

pores are filled with water, creating reducing condi-

tions due to lowered oxygen levels. This reduction, as well

as the movement of iron and manganese, creates distinctive

soil patterns that allow the identification of saturated condi-

tions even when the soil is dry. See also Artesian well; Drink-

ing-water supply

Zoo

Zoos are institutions for exhibiting and studying wild ani-

mals. Many contemporary zoos have also made

environ-

mental education

and the

conservation

of

biodiversity

part of their mission. “Zoo” is a term derived from the Greek

zoion, meaning “living being.” As a prefix it indicates the

topic of animals, such as in zoology (knowledge of animals)

or zoogeography (the distribution and evolutionary

ecology

of animals). As a noun it is a popular shorthand for all

zoological gardens and parks.

Design and operation

Zoological gardens and parks are complex institutions

involving important factors of design, staffing, economics,

and politics. Design of a zoo is a compromise between the

1552

needs of the animals (e.g., light, temperature, humidity,

cover, feeding areas, opportunities for natural behavior), the

requirements of the staff (e.g., offices, libraries, research and

veterinary laboratories, garages, storage sheds), and ame-

nities for visitors (e.g., information, exhibitions, restaurants,

rest areas, theaters,

transportation

).

Zoos range in size from as little as 2 acres (0.8 ha) to

as much as 3,000 acres (1,231 ha), and animal enclosures

may range from small cages to fenced-in fields. The proper

size for each enclosure is determined by many factors, includ-

ing the kind and number of

species

being exhibited and

the extent of the enclosure’s natural or naturalistic landscap-

ing. In small zoos, space is at a premium. Cages and paddocks

are often arranged into taxonomic or zoogeographic pavil-

ions, with visitors walking among the exhibits. As a collec-

tion of animals in a confined and artfully arranged space,

these zoos are called zoological gardens. In larger zoos, more

space is generally available. Enclosures may be bigger, the

landscaping more elaborate, and cages fewer in number.

Nonpredatory species such as hoofed mammals may roam

freely within the confines of the zoo’s outer perimeter. Visi-

tors may walk along raised platforms or ride monorail trains

through the zoo. Lacking the confinement and precise ar-

rangement of a garden, these zoos are called zoological parks.

Some zoos take go a step farther and model themselves after

Africa’s national parks and

game preserves

. Visitors drive

cars or ride buses through these “safari parks,” observing

animals from vehicles or blinds.

A zoo’s many functions are reflected in its staff, which

is responsible for the animals’ well-being, exhibitions, envi-

ronmental education, and conservation programs. There are

several job categories: administrators, office personnel, and

maintenance staff tend to the management of the institution.

Curators are trained

wildlife

biologists responsible for ani-

mal acquisition and transfer, as well as maintaining high

standards of animal care. Keepers perform the routine care of

the animals and the upkeep of their enclosures. Veterinarians

focus on preventive and curative medicine, guard against

contagious disease, heal stress-induced ailments or accidental

injuries, and preside over births and autopsies. Well-trained

volunteers serve as guides and guards, answering questions

and monitoring visitor conduct. Educators and scientists

may also be present for the purpose of environmental educa-

tion and research.

Zoos are expensive undertakings, and their economy

enables or constrains their resources and practices. Few good

zoos produce surplus revenue; their business is service, not

profit. Most perpetually seek new sources of capital from

both public and private sectors, including government sub-

sidies, admission charges, food and merchandise sales, con-

cessionaire rental fees, donations, bequests, and grants. The

funds are used for a variety of purposes, such as daily opera-

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Zoo

tions, animal acquisitions, renovations, expansion, public ed-

ucation, and scientific research. The precise mixture of public

and private funds is situational. As a general rule, public

money provides the large investments needed to start, reno-

vate, or expand a zoo. Private funds are better suited for

small projects and exhibit startup costs.

A variety of public and private interests claim a stake

in a zoo’s mission and management. Those concerned with

the politics of zoos include units of government, regulatory

agencies, commercial enterprises, zoological societies, non-

profit foundations, activist groups, and scholars. They influ-

ence the availability and use of zoo resources by holding the

purse strings and affecting public opinion. Conflict between

the groups can be intense, and ongoing disputes over the

use of zoos as entertainment, the acquisition of “charismatic

megafauna” (big cute animals), and the humane treatment

of wildlife are endemic.

History and purposes

Zoos are complex cultural phenomena. Menageries,

the unsystematic collections of animals that were the progen-

itors of zoos, have a long history. Particularly impressive

menageries were created by ancient societies. The Chinese

emperor Wen Wang (circa 1000

B.C.

) maintained a 1,500

acre (607 ha) “Garden of Intelligence.” The Greek philoso-

pher Aristotle (384-322

B.C.

) studied animal taxonomy from

a menagerie stocked largely through the conquests of Alex-

ander the Great (356-323

B.C.

). Over 1,200 years later, the

menagerie of the Aztec ruler Montezuma (circa

A.D.

1515)

rivaled any European collection of the sixteenth century.

In the main, these menageries had religious, recre-

ational, and political purposes. Ptolemy II of Egypt (300-

251

B.C.

) sponsored great processions of exotic animals for

religious festivals and celebrations. The Romans maintained

menageries of bears,

crocodiles

,

elephants

, and lions for

entertainment. Powerful lords maintained and exchanged

wild and exotic animals for diplomatic purposes, as did Char-

lemagne (

A.D.

768-814), the medieval king of the Franks.

Dignitaries gawked at tamed cheetahs strolling the botanical

gardens of royal palaces in Renaissance Europe. Indeed,

political and social prestige accrued to the individual or

community capable of acquiring and supporting an elaborate

and expensive menagerie.

In Europe, zoos replaced menageries as scholars turned

to the scientific study of animals. This shift occurred in

the eighteenth century, the result of European voyages of

discovery and conquest, the founding of natural history mu-

seums, and the donation of private menageries for public

display. Geographically representative species were collected

and used to study natural history, taxonomy, and physiology.

Some of these zoos were directed by the outstanding minds

of the day. The French naturalist Georges Leopold Cuvier

(1769-1832) was the zoological director of the Jardin de

1553

Plants de Paris (founded in 1793), and the German geogra-

pher Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859) was the first

director of the Berlin Zoological Garden (founded in 1844).

The first zoological garden for expressly scientific purposes

was founded by the Zoological Society of London in 1826;

its establishment marks the advent of modern zoos.

Despite their scientific rhetoric, zoological gardens and

parks retained their recreational and political purposes. Late

nineteenth century visitors still baited bears, fed elephants,

and marveled at the exhausting diversity of life. In the United

States, zoos were regarded as a cultural necessity, for they

reacquainted harried urbanites with their

wilderness

fron-

tier heritage and proved the natural and cultural superiority

of North America. As if

recreation

, politics, and science

were not enough, an additional element was introduced in

North American zoos: conservation. North Americans had

succeeded in decimating much of the continent’s wildlife,

driving the

passenger pigeon

(Ectopistes migratorius)to

extinction

, the American

bison

(Bison bison) to endanger-

ment, and formerly common wildlife into rarity. It was be-

lieved that zoos would counteract this wasteful slaughter of

animals by promoting their wise use. At present, zoos claim

similar purposes to explain and justify their existence, namely

recreation, education, and conservation.

Evaluating zoos

Critics of zoos contend they are antiquated, counter-

productive, and unethical; that field ecology and

wildlife

management

make them unnecessary to the study and

conservation of wildlife; and that zoos distort the public’s

image of

nature

and animal behavior, imperil rare and en-

dangered wildlife for frivolous displays, and divert attention

from saving natural

habitat

. Finally, critics hold that zoos

violate humans’ moral obligations to animals by incarcerating

them for a trivial interest in recreation. Advocates counter

these claims by insisting that most zoos are modern, neces-

sary, and humane, offering a form of recreation that is benign

to animal and human alike and is often the only viable place

from which to conduct sustained behavioral, genetic, and

veterinary research.

Zoos are an important part of environmental educa-

tion. Indeed, some advocates have proposed “bioparks” that

would integrate aquariums, botanical gardens, natural history

museums, and zoos. Finally, advocates claim that animals in

zoos are treated humanely. By providing for their nutritional,

medical, and security needs, zoo animals live long and digni-

fied lives, free from hunger, disease, fear, and predation.

The arguments of both critics and advocates have

merit, and in retrospect, zoos have made substantial progress

since the turn of the century. In the early 1900s, many

zoos collected animals like postage stamps, placing them in

cramped and barren cages with little thought to their com-

fort. Today, zoos increasingly use large naturalistic enclo-

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Zooplankton

sures and house social animals in groups. They often special-

ize in zoogeographic regions, permitting the creation of

habitats which plausibly simulate the

climate

,

topography

,

flora

, and

fauna

of a particular

environment

. Additionally,

many zoos contribute to the protection of biodiversity by

operating captive-breeding programs, propagating

endan-

gered species

, and restoring destroyed species to suitable

habitat.

This progress notwithstanding, zoos have limitations.

Statements that zoos are “arks” of biodiversity, or that zoos

teach people how to manage the “megazoo” called nature,

greatly overstate their uses and lessons. Zoos simply cannot

save, manage, and reconstruct nature once its genetic, spe-

cies, and habitat diversity is destroyed. That said, the promo-

tion by zoos of environmental education and biodiversity

conservation is an important role in the defense of the natural

world.

[William S. Lynn]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Croke, V. The Modern Ark: The Story of Zoos: Past, Present, and Future.

Collingdale: DIANE Publishing Co., 2000.

McKenna, V., W. Travers, and J. Wray, eds. Beyond the Bars: The Zoo

Dilemma. Northamptonshire, UK: Thorsons Publishing Group, 1988.

1554

Page, J. Zoo: The Modern Ark. New York: Facts On File, 1990.

P

ERIODICALS

Foose, T. J. “Erstwild & Megazoo.” Orion Nature Quarterly 8 (Spring

1989): 60–63.

Robinson, M. H. “Beyond the Zoo: The Biopark.” Defenders 62 (November-

December 1987): 10–17.

Stott, J. R. “The Historical Origins of the Zoological Park in American

Thought.” Environmental Review 5 (Fall 1981): 52–65.

Zooplankton

Aquatic animals and protozoans whose movements are

largely dependent upon currents. This diverse assemblage

includes organisms that feed on bacteria,

phytoplankton

,

and other zooplankton, as well as organisms that may not

feed at all. Zooplankton may be divided into holoplankton,

organisms which spend their entire lives as

plankton

, such

as

krill

, and meroplankton, organisms that exist in the plank-

ton for only part of their lives, such as crab larvae. Fish may

live their entire lives in the water column, but are only

classified as zooplankton while in their embryonic and larval

stages.

ZPG

see

Environmental Stress Index

Historical Chronology

1798 Essay on the Principle of Population published by

Thomas Robert Malthus, in which he warned about

the dangers of unchecked population growth.

1830 World population is one billion.

1849 U.S. Department of the Interior established.

1854 Henry David Thoreau publishes Walden, a work

that inspired many people to live simply and in

harmony with nature.

1864 Yosemite in California becomes the first state park

in the United States.

1864 George Perkins Marsh publishes Man and Nature,

described by some environmentalists as the foun-

tainhead of the conservation movement.

1869

Ernst Haeckel coins the term ecology to describe

“the body of knowledge concerning the economy

of nature.”

1872

Yellowstone in Wyoming becomes the first na-

tional park.

1875

American Forestry Association founded to encour-

age wise forest management.

1879

U.S. Geological Survey established.

1890

Yosemite becomes a national park.

1892

John Muir founds the Sierra Club to preserve the

Sierra Nevada mountain chain.

1892

Henry S. Salt publishes Animal Rights Considered

in Relation to Social Progress, a landmark work on

animal rights and welfare.

1555

1892 Adirondack Park established by New York State

Constitution, which mandated that the region re-

main forever wild.

1898 Rivers and Harbors Act established in an effort to

control pollution of navigable waters.

1900 Lacey Act regulating interstate shipment of wild

animals in the United States is passed.

1902 U.S. Bureau of Reclamation established.

1905 National Audubon Society formed.

1908 Chlorination is used extensively in U.S. water treat-

ment plants for the first time.

1913 Construction of Hetch-Hetchy Valley Dam ap-

proved to provide water to San Francisco; however,

the dam also floods areas of Yosemite National

Park.

1914 Martha, the last passenger pigeon, dies in the Cin-

cinnati Zoo.

1916 United States National Park Service established.

1918 Save-the-Redwoods League founded.

1918 U.S. and Canada sign treaty restricting the hunting

of migratory birds.

1920 Mineral Leasing Act enacted to regulate mining

on federal land.

1922 Izaak Walton League founded.

1924 Gila National Forest in New Mexico is designated

the first wilderness area.

1930 Dust Bowl.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Historical Chronology

1933 Tennessee Valley Authority created to assess impact

of hydropower on the environment.

1934 Taylor Grazing Act enacted to regulate grazing on

federal land.

1935 U.S. Soil Conservation Service established to study

and curb soil erosion.

1935 Wilderness Society founded by Aldo Leopold.

1936 National Wildlife Federation established.

1943 Alaska Highway completed, linking lower United

States and Alaska.

1944 Norman Borlaug begins his work on high-yielding

cropvarieties.

1946 U.S. Bureau of Land Management created.

1946 Atomic Energy Commission established to study

the applications of nuclear power. It was later

dissolved in 1975, and its responsibilities were

transferred to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission

and Energy Research and Development Adminis-

tration.

1947 Defenders of Wildlife founded, superseding De-

fenders of Furbearers and the Anti-Steel-Trap

League, to protect wild animals and their habitat.

1949 Aldo Leopold publishes A Sand CountyAlmanac,

in which he sets guidelines for the conservation

movement and introduces the concept of a land

ethic.

1952 Oregon becomes first state to adopt a significant

program to control air pollution.

1954 Humane Society founded in United States.

1956 Construction of Echo Park Dam on the Colorado

River is aborted, due in large part to the efforts of

environmentalists.

1959 St. Lawrence Seaway is completed, linking the At-

lantic Ocean to the Great Lakes.

1961 Agent Orange is sprayed in Southeast Asia,

exposing nearly 3 million American servicemen to

dioxin, a probable carcinogen.

1962 Silent Spring published by Rachel Carson to docu-

ment the effects of pesticides on the environment.

1556

1963 First Clean Air Act passed in the United States.

1963 Nuclear Test Ban Treaty signed by the United

States and the Soviet Union to stop atmospheric

testing of nuclear weapons.

1964 Wilderness Act passed, which protects wild areas

in theUnited States.

1965 Water Quality Act passed, establishing federal

water quality standards.

1966 Eighty people die in New York City due to pollu-

tion-related causes.

1967 Supertanker Torrey Canyon spills oil off the coast

of England.

1967 Environmental Defense Fund established to save

the osprey from DDT.

1967 American Cetacean Society founded to protect

whales, dolphins, porpoises, and other cetaceans.

Considered the oldest whale conservation group in

the world.

1968 Wild and Scenic Rivers Act and National Trails

System Act passed to protect scenic areas from

development.

1969 Greenpeace founded.

1970 First Earth Day celebrated on April 22.

1970 National Environmental Policy Act passed, requir-

ing environmental impact statements for projects

funded or regulated by federal government.

1970 Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) created.

1971 Consultative Group on International Agricultural

Research (CGIAR) founded to improve food pro-

duction in developing countries.

1972 U.N. Conference on the Human Environment held

in Stockholm to address environmental issues on a

global level.

1972 Clean Water Act passed.

1972 Use of DDT is phased out in the United States.

1972 Coastal Zone Management Act and Marine Pro-

tection, Research, and Sanctuaries Act passed.