Environmental Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Filtration

them to miss the fibers, but when the air stream bends to

go around the fibers the momentum, of the particles is too

much to let them remain with the stream, so that they are

“centrifuged out” onto the fibers (impaction). By electropho-

resis, still other particles may be attracted to the fibers by

electric charges of opposite sign on the particles and on the

fibers. Finally, particles may simply be larger than the space

between fibers, and be sifted out of the air in a process called

sieving.

Filters are also formed by a process in which polymers

such as cellulose esters are made into a film out of a solution

in an organic solvent containing water. As the solvent evapo-

rates, a point is reached at which the water separates out as

microscopic droplets, in which the polymer is not soluble.

The final result is a film of polymer full of microscopic holes

where the water droplets once were. Such filters can have

pore sizes from a small fraction of a micrometer to a few

micrometers. (One micrometer equals 0.00004 in) These

are called membrane filters.

Another form of membrane filter is formed from the

polymer called polycarbonate. A thin film of this material

is fastened to a surface of

uranium

metal and placed in a

nuclear reactor for a time. In the reactor, the uranium under-

goes

nuclear fission

, and gives off particles called fission

fragments, atoms of the elements formed when the uranium

atoms split. Every place that an atom from the fissioning

uranium passes through the film is disturbed on a molecular

scale. After removal from the reactor, if the polymer sheet

is soaked in alkali, the disturbed material is dissolved. The

amount of material dissolved is controlled by the temperature

of the solution and the amount of time the film is treated.

Since the fission fragments are very energetic, they travel in

straight lines, and so the holes left after the alkali treatment

are very straight and round. Again, pore sizes can be from

a small fraction of a micrometer to a few micrometers. These

filters are known by their trade name, Nuclepore.

In both types of membrane filters, the small pore size

increases the role of sieving in particle removal. Because of

their very simple structure, Nuclepore filters have been much

studied to understand

filtration

mechanisms, since they are

far easier to represent mathematically than a random ar-

rangement of fibers.

It was mentioned above that small particles are col-

lected because of their Brownian motion, while larger parti-

cles are removed by interception, impaction, and sieving.

Under many conditions, a particle of intermediate size may

pass through, too large for Brownian diffusion, and too small

for impaction, interception, or sieving. Hence many filters

may show a penetration maximum for particles of a few

tenths of a micrometer. For this reason, standard methods

of filter testing specify that the

aerosol

test for determining

the efficiency of filters should contain particles in that size

557

range. This phenomenon has also been used to select rela-

tively uniform particles of that size out of mixtures of

many sizes.

In circumstances where filter strength is of paramount

importance, such as in industrial filters where a large air

flow must pass through a relatively small filter area, filters

of woven cloth are used, made of materials ranging from

cotton to glass fiber and asbestos, these last for use when

very hot gases must be filtered. The woven fabric itself is

not a particularly good filter, but it retains enough particles

to form a particle cake on the surface, and that soon becomes

the filter. When the cake becomes thick enough to slow

airflow to an unacceptable degree, the air flow is interrupted

briefly, and the filters are shaken to dislodge the filter cake,

which falls into bins at the bottom of the filters. Then

filtration is resumed, allowing the cloth filters to be used

for months before being replaced. A familiar domestic exam-

ple is the bag of a home vacuum cleaner. Cement plants

and some electric

power plants

use dozens of cloth bags

up to several feet in diameter and more than ten feet (three

meters) in length to remove particles from their waste gases.

Otherwise poor filters can be made efficient by making

them thick. A glass tube can be partially plugged with a wad

of cotton or glass fiber, then nearly filled with crystals of

sugar or naphthalene and used as a filter; this is advantageous

since sugar can be dissolved in water, or naphthalene will

sublime away if gently heated, leaving behind the collected

particles. See also Baghouse; Electrostatic precipitation; Odor

control; Particulate

[James P. Lodge Jr.]

Filtration

A common technique for separating substances in two physi-

cal states. For example, a mixture of solid and liquid can be

separated into its components by passing the mixture

through a filter paper. Filtration has many environmental

applications. In water purification systems, impure water is

often passed through a charcoal filter to remove the solid

and gaseous contaminants that give water a disagreeable

odor, color, or taste. Trickling

filters

are used to remove

solid wastes in plants. Solid and liquid contaminants in waste

industrial gases can be removed by passing them through a

filter prior to

discharge

in a smokestack.

Fire

see

Prescribed burning; Wildfire

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Fire ants

Fire ants

Two distinct

species

of fire ants (genus Solenopsis) from

South America have been introduced into the United States

this century. The South American black fire ant (S. richteri)

was first introduced into the United States in 1918. Its close

relative, the red fire ant (S. wagneri), was introduced in 1940,

probably escaping from a South American freighter docked

in Mobile, Alabama. Both species became established in the

southeastern United States, spreading into nine states from

Texas across to Florida and up into the Carolinas. It is

estimated that they have infested over 320 million acres (130

million ha) covering 13 states as well as Puerto Rico.

Successful

introduced species

are often more aggres-

sive than their native counterparts, and this is definitely true

of fire ants. They are very small, averaging 0.2 in (5 mm)

in length, but their aggressive, swarming behavior makes

them a threat to livestock and pets as well as humans. These

industrious, social insects build their nests in the ground—

the location is easily detected by the elevated earthen mounds

created from their excavations. The mounds are 18–36 in

(46–91 cm) in diameter and may be up to 36 in (91 cm)

high, although mounds are generally 6–10 in (15–25 cm)

high. Each nest contains as many as 25,000 workers, and

there may be over 100 nests on an acre of land.

If the nest is disturbed, fire ants swarm out of the

mound by the thousands and attack with swift ferocity.

As with other aspects of ant behavior, a chemical alarm

pheromone is released that triggers the sudden onslaught.

Each ant in the swarm uses its powerful jaws to bite and latch

onto whatever disturbed the nest, while using the stinger on

the tip of its abdomen to sting the victim repeatedly. The

intruder may receive thousands of stings within a few

seconds.

The toxin produced by the fire ant is extremely potent,

and it immediately causes an intense burning pain that may

continue for several minutes. After the pain subsides, the

site of each sting develops a small bump which expands and

becomes a tiny, fluid-filled blister. Each blister flattens out

several hours later and fills with pus. These swollen pustules

may persist for several days before they are absorbed and

replaced by scar tissue. Fire ants obviously pose a problem

for humans. Some people may become sensitized to fire ant

venom, have a generalized systematic reaction, and go into

anaphylactic shock. Fire-ant induced deaths have been re-

ported. Because these species prefer open, grassy yards or

fields, pets and livestock may fall prey to fire ant attacks

as well.

Attempts to eradicate this

pest

involved the use of

several different generalized pesticides, as well as the wide-

spread use of

gasoline

either to burn the nest and its inhabit-

ants or to kill the ants with strong toxic vapors. Another

558

approach involved the use of specialized crystalline pesticides

which were spread on or around the nest mound. The work-

ers collected them and took them deep into the nest, where

they were fed to the queen and other members of the colony,

killing the inhabitants from within. A more recent method

involves the release of a natural predator of the fire ant, the

“phorid” fly. The fly releases an egg into the fire ant. The

larva then eats the ant’s brain while releasing an

enzyme

.

The enzyme systematically destroys the joints causing the

ant’s head to fall off. The flies were released in 11 states as

of 2001 and seem to be slowly inhibiting the growth of the

fire ant population. As effective as some of these methods

are, fire ants are probably too numerous and well established

to be completely eradicated in North America.

[Eugene C. Beckham]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Holldobler, B. The Ants. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1990.

Taber, Stephen Welton. Fire Ants. Texas A&M University Press, 2000.

P

ERIODICALS

Vergano, Dan. “Decapitator Flies will Fight Fire Ants.” USA Today, No-

vember 20, 2000.

O

THER

“Imported Fire Ant.” NAPIS Page for BioControl Host. April 2001 [cited

May 2002]. <http://www.ceris.purdue.edu/napis/pests/ifa/ifabc.html>.

“Invasive Species and Pest Management: Imported Fire Ant.” Animal and

Plant Health Inspection Service. May 2002 [cited May 2002]. <http://

www.aphis.usda.gov>.

First World

The world’s more wealthy, politically powerful, and industri-

ally developed countries are unofficially, but commonly, des-

ignated as the First World. The term differentiates the pow-

erful, capitalist states of Western Europe and North America

and Japan from the (formerly) communist states (

Second

World

) and from the nonaligned, developing countries

(

Third World

) in world systems theory. In common usage,

First World refers mainly to a level of economic strength.

The level of industrial development of the First World,

characterized by an extensive infrastructure, mechanized

production, efficient and fast transport networks, and perva-

sive use of high technology, consumes huge amounts of

natural resources

and requires an educated and skilled

work force. However, such a system is usually highly profit-

able. Often depending upon raw materials imported from

poorer countries (wood, metal ores,

petroleum

, food, and

so on), First World countries efficiently produce goods that

less developed countries

desire but cannot produce them-

selves, including computers, airplanes, optical equipment,

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Fish kills

and military hardware. Generally, high domestic and inter-

national demand for such specialized goods keeps First

World countries wealthy, allowing them to maintain a high

standard of material consumption, education, and health

care for their citizens.

Fish and Wildlife Service

The United States Fish & Wildlife Service based in Wash-

ington, D.C., is charged with conserving, protecting, and

enhancing fish,

wildlife

, and their habitats for the benefit

of the American people. As a division of the

U.S. Depart-

ment of the Interior

, the Service’s primary responsibilities

are for the protection of migratory birds,

endangered spe-

cies

, freshwater and anadromous (saltwater

species

that

spawn in freshwater rivers and streams) fisheries, and certain

marine mammals.

In addition to its Washington, D.C., headquarters,

the Service maintains seven regional offices and a number

of field units. Those include national wildlife refuges, na-

tional fish hatcheries, research laboratories, and a nationwide

network of law enforcement agents.

The Service manages 530 refuges that provide habitats

for migratory birds, endangered species, and other wildlife.

It sets migratory bird

hunting

regulations, and leads an

effort to protect and restore endangered and threatened ani-

mals and plants in the United States and other countries.

Service scientists assess the effects of contaminants on

wildlife and habitats. Its geographers and cartographers work

with other scientists to map

wetlands

and carry out pro-

grams to slow wetland loss, or preserve and enhance these

habitats. Restoring fisheries that have been depleted by

over-

fishing

,

pollution

, or other

habitat

damage is a major pro-

gram of the Service. Efforts are underway to help four impor-

tant species: lake trout in the upper

Great Lakes

; striped

bass in both the

Chesapeake Bay

and Gulf Coast; Atlantic

salmon

in New England; and salmonid species of the Pacific

Northwest.

Fish and Wildlife biologists working with scientists

from other federal and state agencies, universities, and pri-

vate organizations develop recovery plans for endangered and

threatened species. Among its successes are the

American

alligator

, no longer considered endangered in some areas,

and a steadily increasing

bald eagle

population.

Internationally, the Service cooperates with 40 wildlife

research and

wildlife management

programs, and provides

technical assistance to many other countries. Its 200 special

agents and inspectors help enforce wildlife laws and treaty

obligations. They investigate cases ranging from individual

migratory bird hunting violations to large-scale

poaching

and commercial trade in protected wildlife.

559

It its “Vision for the Future” statement, the Fish and

Wildlife Service states its mission to “provide leadership to

achieving a national net gain of fish and wildlife and the

natural systems which support them.” Into the twenty-first

century, this vision statement calls for new

conservation

compacts with all citizens to increase the value of the United

States wildlife holdings in number and

biodiversity

, and

to provide increased opportunities for the public to use,

associate with, learn about and enjoy America’s wildlife

wealth.

[Linda Rehkopf]

R

ESOURCES

O

THER

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Vision for the Future. Washington, DC:

U.S. Government Printing Office, 1991.

O

RGANIZATIONS

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Email: contact@fws.gov, <http://

www.fws.gov>

Fish farming

see

Blue revolution (fish farming)

Fish kills

Fishing has long been a major provider of food and livelihood

to people throughout the world. In the United States, 50

million people enjoy fishing as an outdoor recreation—38

million in fresh water and 12 million in salt water. Com-

bined, they spend over $315 million annually on this sport.

It is no surprise, then, that public attitude towards factors

that influence fishing is strong.

The

Environmental Protection Agency

(EPA) is

charged with overseeing the quality of the nation’s water-

ways. In 1977 they received information on 503 separate

incidents in which 16.5 million fish were killed. In 1974, a

record 47 million fish were killed in the Black River near

Essex, Maryland, by a

discharge

from a sewage plant.

Fish kills can result from natural as well as human

causes. Natural causes include sudden changes in tempera-

ture, oxygen depletion, toxic gases, epidemics of viruses and

bacteria, infestations of

parasites

, toxic algal blooms, light-

ning,

fungi

, and other similar factors. Human influences

that lead to fish kills include

acid rain

, sewage

effluent

,

and toxic spills.

In a 10-year study of the causes of 409 documented

fish kills totaling 3.6 million fish in the state of Missouri,

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Fish kills

S. M. Czarnezki determined the percentage contributions

as: 26% municipal-related (sewage effluent), 17% from ag-

ricultural activities, 11% from industrial operations, 8% by

transportation

accidents, 7% each by oxygen depletions,

nonindustrial operations, and mining, 4% by disease, 3% by

“other” factors, and 10% as undetermined.

Fish kills may occur quite rapidly, even within minutes

of a major toxic spill. Usually, however, the process takes

days or even months, especially in natural causes. Experi-

enced fishery biologists usually need a wide variety of physi-

cal, chemical, and biological tests of the

habitat

and fish

to determine the exact causative agent or agents. The investi-

gative procedure is often complex and may require a lot

of time.

Species

of fish vary in their susceptibility to the differ-

ent factors that contribute to die-offs. Some species are

sensitive to almost any disturbance, while other fish are

tolerant of changes. As discussed below, predatory fish at

the top of the

food chain/web

are typically the first fish

affected by toxic substances that accumulate slowly in the

water.

The most common contributor to fish kills by natural

causes is oxygen depletion, which occurs when the amount of

oxygen utilized by

respiration

,

decomposition

, and other

processes exceeds oxygen input from the

atmosphere

and

photosynthesis

. Oxygen is more soluble in cold than warm

water. Summer fish kills occur when lakes are thermally

stratified. If the lake is eutrophic (highly productive), dead

plant and animal matter that settles to the bottom undergoes

decomposition, utilizing oxygen. Under windless conditions,

more oxygen will be used than is gained, and animals like

fish and

zooplankton

often die from suffocation.

Winter fish kills can also occur. Algae can photosyn-

thesize even when the lake is covered with ice because sun-

light can penetrate through the ice. However, if heavy snow-

fall accumulates on top of the ice, light may not reach the

underlying water, and the

phytoplankton

die and sink to

the bottom.

Decomposers

and respiring organisms again

use up the remaining oxygen and the animals eventually die.

When the ice melts in the spring, dead fish are found floating

on the surface. This is a fairly common occurrence in many

lakes in Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and surrounding

states. For example, dead alewives (Alosa pseudoharengus)

often wash up on the southwestern shore of Lake Michigan

near Chicago during spring thaws following harsh winters.

In summer and winter, artificial

aeration

can help

prevent fish kills. The addition of oxygen through aeration

and mixing is one of the easiest and cheapest methods of

dealing with low oxygen levels. In intensive

aquaculture

ponds, massive fish deaths from oxygen depletion are a con-

stant threat. Oxygen sensors are often installed to detect low

560

oxygen levels and trigger the release of pure oxygen gas from

nearby cylinders.

Natural fish kills can also result from the release of

toxic gases. In 1986, 1,700 villagers living on the shore

of Lake Nyos, Cameroon, mysteriously died. A group of

scientists sent to investigate determined that they died of

asphyxiation. Evidently a

landslide

caused the trapped

car-

bon

dioxide-rich bottom waters to rapidly rise to the surface

much like a popped champagne bottle. The poisonous gas

killed everyone in its downwind path. Fish in the upper

oxygenated waters of the lake were also killed as the

carbon

dioxide

passed through.

Hydrogen

sulfide (H

2

S), a foul-smelling gas naturally

produced in the oxygen-deficient sediments of eutrophic

lakes, can also cause fish deaths. Even in oxygenated waters,

high H

2

S levels can cause a condition in fish called “brown

blood.” The brown color of the blood is caused by the forma-

tion of sulfhemoglobin, which inhibits the blood’s oxygen-

carrying capacity. Some fish survive, but sensitive fish such

as trout usually die.

Fish kills can also result from toxic algal blooms. Some

bluegreen algae in lakes and dinoflagellates in the ocean

release

toxins

that can kill fish and other vertebrates, includ-

ing humans. For example, dense blooms of bluegreen algae

such as Anabaena, Aphanizomenon, and Microcystis have

caused fish kills in many farm ponds during the summer.

Fish die not only from the toxins but also from asphyxiation

resulting from decomposition of the mass of algae that also

die due to lack of sunlight in the densely-populated lake

water. In marine waters, toxic dinoflagellate blooms called

red tides are notorious for causing massive fish kills. For

example, blooms of Gymnodinium or Gonyaulax periodically

kill fish along the East and Gulf Coasts of the United States.

Die-offs of

salmon

in aquaculture pens along the southwest-

ern shoreline of Norway have been blamed on these organ-

isms. Millions of dollars can be lost if the fish are not moved

to clear waters. Saxitoxin, the toxic chemical produced by

Gonyaulax, is 50 times more lethal than strychnine or curare.

Pathogens and parasites can also contribute to fish

kills. Usually the effect is more secondary than direct. Fish

weakened by parasites or infections of bacteria or viruses

usually are unable to adapt to and survive changes in water

temperature and chemistry. Under stressful conditions of

over-crowding and malnourishment, gizzard shad often die

from minor infestations of the normally harmless bacterium

Aeromonas hydrophila. In the same way, fungal infections

such as Ichthyophonus hoferia can contribute to fish kills.

Most fresh water aquarium keepers are familiar with the

threat of “ick” for their fish. The telltale white spots under

the epithelium of the fins, body, and gills are caused by the

protozoan parasite Ichthyophthirius multifiliis.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Fisheries and Oceans Canada

Changes in

pH

of lakes resulting from

acid

rain are

a modern example of how humans can cause fish kills.

Atmo-

spheric pollutants

such as

nitrogen

dioxide and

sulfur

dioxide

released from automobiles and industries mix with

water vapor and cause the rainwater to be more acid than

normal (>pH 6.5). Nonprotected lakes downwind that re-

ceive this rainfall increase in acidity, and sensitive fish even-

tually die. Most of the once-productive trout streams and

lakes in the southern half of Norway are now devoid of these

prized fish. Sweden has combatted this problem by adding

enormous quantities of lime to their affected lakes in the

hope of neutralizing the acid’s effects.

Sewage treatment

plants add varying amounts of

treated effluent to streams and lakes. Sometimes during

heavy rainfall raw sewage escapes the treatment process and

pollutes the aquatic

environment

. The greater the organic

matter that comprises the effluent, the more decomposition

occurs, resulting in oxygen usage. Scientists call this the

biological or

biochemical oxygen demand

(BOD), the

quantity of oxygen required by bacteria to oxidize the

or-

ganic waste

aerobically to carbon dioxide and water. It is

measured by placing a sample of the

wastewater

in a glass-

stoppered bottle for five days at 71 degrees Fahrenheit (20

degrees Celsius) and determining the amount of oxygen

consumed during this time. Domestic sewage typically has

a BOD of about 200 milligrams per liter, or 200

parts per

million

(ppm); rates for industrial waste may reach several

thousand milligrams per liter. Reports of fish kills in indus-

trialized countries have greatly increased in recent years.

Sewage effluent not only kills fish; it can also create a barrier

to fish migrating upstream because of the low oxygen levels.

For example, coho salmon will not pass through water with

oxygen levels below 5 ppm. Oxygen depletion is often more

detrimental to fish than thermal shock.

Toxic

chemical spills

, whether via sewage treatment

plants or other sources, are the major cause of fish kills.

Sudden discharges of large quantities of highly toxic

substances usually cause massive death of most aquatic

life. If they enter the

ecosystem

at sublethal levels over

a long time, the effects are more subtle. Large predatory

or omnivorous fish are typically the first ones affected.

This is because toxic

chemicals

like methyl

mercury

,

DDT, PCBs, and other organic pollutants have an affinity

for fatty tissue and progressively accumulate in organisms

up the food chain. This is called the principle of

biomagni-

fication

. Unfortunately for human consumers, these fish

do not usually die right away, so people who eat a lot

of tainted fish become sick and possibly die. Such is the case

for

Minamata disease

, named for the first documented

connection between the death of fishermen and methyl

mercury contamination.

[John Korstad]

561

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Czarnezki, J. M. A Summary of Fish Kill Investigations in Missouri, 1970–

1979. Columbia, MO: Missouri Dept. of Conservation, 1983.

Ehrlich, P. R., A. H. Ehrlich, and J. P. Holdren. Ecoscience: Population,

Resources, Environment. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman, 1977.

Goldman, C. R., and A. J. Horne. Limnology. New York: McGraw-

Hill, 1983.

Hill, D. M. “Fish Kill Investigation Procedures.” In Fisheries Techniques,

edited by L. A. Nielson and D. L. Johnson. Bethesda, MD: American

Fisheries Society, 1983.

Meyer, F. P., and L. A. Barclay, eds. Field Manual for the Investigation of

Fish Kills. Washington, DC: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 1990.

Moyle, P. B., and J. J. Cech Jr. Fishes: An Introduction to Ichthyology. 2nd

ed. New York: Prentice-Hall, 1988.

P

ERIODICALS

Keup, L. E. “How to ’Read’ A Fish Kill.” Water and Sewage Works 12

(1974): 48–51.

Fish nets

see

Drift nets; Gill nets

Fisheries and Oceans Canada

The Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) in Canada

was created by the Department of Fisheries and Oceans Act

on April 2, 1979. This act formed a separate government

department from the Fisheries and Marine Service of the

former Department of Fisheries and the Environment. The

new department was needed, in part, because of increased

interest in the management of Canada’s oceanic resources,

and also because of the mandate resulting from the unilateral

declaration of the 200-nautical-mi Exclusive Economic

Zones in 1977.

At its inception, the DFO assumed responsibility for

seacoast and inland fisheries, fishing and recreational vessel

harbors, hydrography and ocean science, and the coordina-

tion of policy and programs for Canada’s oceans. Four main

organizational units were created: Atlantic Fisheries, Pacific

and Freshwater Fisheries, Economic Development and Mar-

keting, and Ocean and Aquatic Science. Among the activi-

ties included in the department’s original mandate were:

comprehensive husbandry of fish stocks and protection of

habitat

; “best use” of fish stocks for optimal socioeconomic

benefits; adequate hydrographic surveys; the acquisition of

sufficient knowledge for defense,

transportation

, energy

development and fisheries, with provision of such informa-

tion to users; and continued development and maintenance

of a national system of harbors.

Since its inception, the department’s mandate has

changed in minor ways, to include new terminology such as

“sustainability” and to include Canada’s “ecological inter-

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Floatable debris

ests.” Recently, attention has been given to support those

who make their living or benefit from the sea. This constitu-

ency includes the public first, but the DFO also directs

its efforts toward commercial fishers, fish plant workers,

importers, aquaculturists, recreational fishers, native fishers,

and the ocean manufacturing and service sectors. There are

now six DFO divisions: Science, Atlantic Fisheries, Pacific

Fisheries, Inspection Services, International, and Corporate

Policy and Support administered through six regional offices.

A primary focus of DFO’s current work is the failing

cod and groundfish stocks in the Atlantic; the department

has commissioned two major inquiries in recent years to

investigate those problems. In addition, the DFO has in-

creased regulation of foreign fleets, and works to manage

straddling stocks in the Atlantic

Exclusive Economic Zone

through the North Atlantic Fisheries Organization, the Pa-

cific drift nets fisheries, recreational fishing and

aquaculture

development. In 1992, management problems in the major

fisheries arose on both the Pacific and Atlantic coasts. Amer-

ican fisheries managers reneged on quotas established

through the Pacific

Salmon

Treaty, northern cod stocks in

Newfoundland virtually failed, and the Aboriginal Fishing

Strategy was adopted as part of a land claim settlement on

the Pacific coast.

There are several major problems associated with

ocean resource and environment management in Canada—

problems that the DFO has neither the resources, the legisla-

tive infrastructure, nor the political will to address. One

result of this has been the steady decline of commercial fish

stocks, highlighted by the virtual collapse of Atlantic cod

(Gadus callarias), which is Canada’s, and perhaps, the Atlan-

tic’s most historically significant fishery. A second result has

been an increased need to secure international agreements

with Canada’s ocean neighbors. A third result of social sig-

nificance is the perception that fisheries have been used in

a political sense in cases of regional economic incentives

and land claims settlements. See also Commercial fishing;

Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO), Canada

[David A. Duffus]

Fishing

see

Commercial fishing; Drift nets; Gill

nets

Fission

see

Nuclear fission

562

Floatable debris

Floatable debris is buoyant

solid waste

that pollutes water-

ways. Sources include boats and shipping vessels, storm water

discharge

, sewer systems, industrial activities, offshore drill-

ing, recreational beaches, and landfills. Even waste dumped

far from a water source can end up as floatable debris when

flooding

, high winds, or other weather conditions transport

it into rivers and streams.

According to the U.S.

Environmental Protection

Agency

(EPA), floatable debris is responsible for the death

of over 100,000 marine mammals and one million seabirds

annually.

Seals

,

sea lions

,

manatees

,

sea turtles

, and

other marine creatures often mistake debris for food, eating

objects that block their intestinal tract or cause internal

injury. They can also become entangled in lost fishing nets

and line, six-pack rings, or other objects.

Fishing nets lost at sea catch tons of fish that simply

decompose, a phenomenon known as “ghost fishing.” Often,

seabirds are ensnared in these nets when they try to eat

the fish.

Lost nets and other entrapping debris are also a danger

for humans who swim, snorkel, or scuba dive. And biomedi-

cal waste and sewage can spread disease in recreational wa-

ters. Floatable debris takes a significant financial toll as well.

It damages boats, deters tourism, and negatively impacts the

fishing industry.

[Paula Anne Ford-Martin]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Coe, James, and Donald Rogers, eds. Marine Debris: Sources, Impacts, and

Solutions New York: Springer-Verlag, 1996.

P

ERIODICALS

Miller, John. “Solving the Mysteries of Ocean-borne Trash.” U.S. News &

World Report 126, no.14 (April 1999): 48.

O

THER

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Water, Oceans and

Coastal Protection Division. Assessing and Monitoring Floatable Debris—

Draft. [cited May 11, 2002]. <http://www.epa.gov/owow/oceans/debris/

floatingdebris>.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Water, Oceans and

Coastal Protection Division. Turning the Tide on Trash: A Marine Debris

Curriculum [cited May 2002]. <http://www.epa.gov/owow/OCPD/Ma-

rine/contents.htm>.

O

RGANIZATIONS

The Center for Marine Conservation, 1725 DeSales Street, N.W., Suite

600, Washington, DC USA 20036 (202) 429-5609, Fax: (202) 872-0619,

Email: cmc@dccmc.org, http://www.cmc-ocean.org

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Flooding

Flooding in Texas caused by Hurricane Beulah in 1967. (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.)

Flooding

Technically, flooding occurs when the water level in any

stream, river, bay, or lake rises above bank full. Bays may

flood as the result of a tsunami or tidal wave induced by an

earthquake

or volcanic eruption; or as a result of a tidal

storm surge caused by a

hurricane

or tropical storm moving

inland. Streams, rivers and lakes may be flooded by high

amounts of surface

runoff

resulting from widespread precip-

itation or rapid snow melt. On a smaller scale, flash floods

due to extremely heavy precipitation occurring over a short

period of time can flood streams, creeks, and low lying areas

in a matter of a few hours. Thus, there are various temporal

and spatial scales of flooding. Historical evidence suggests

that flooding causes greater loss of life and property than

any other natural disaster. The magnitude, seasonality, fre-

quency, velocity, and load are all properties of flooding which

are studied by meteorologists, climatologists, and hydrolo-

gists.

Spring and winter floods occur with some frequency

primarily in the mid-latitude regions of the earth, and partic-

ularly where continental

climate

is the norm. Five climatic

563

features contribute to the spring and winter flooding poten-

tial of any individual year or region: 1) heavy winter snow

cover; 2) saturated soils or soils at least near their

field

capacity

for storing water; 3) rapid melting of the winter’s

snow pack; 4) frozen

soil

conditions which limit

infiltration

;

and 5) somewhat heavy rains, usually from large scale cy-

clonic storms. Any combination of three of these five climatic

features usually leads to some type of flooding. This type of

flooding can cause hundreds of millions of dollars in property

damage, but it can usually be predicted well in advance,

allowing for evacuation and other protective action to be

taken (sandbagging, for instance). In some situations flood

control measures such as stream or channel diversions,

dams

, and levees can greatly reduce the risk of flooding.

This is more often done in

floodplain

areas with histories

of very damaging floods. In addition,

land use

regulations,

encroachment statutes and building codes are often intended

to protect the public from the risk of flooding.

Flash flooding is generally caused by violent weather,

such as severe thunderstorms and hurricanes. This type of

flooding more frequently occurs during the warm season

when convective thunderstorms develop more frequently.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Floodplain

Rainfall intensity is so great that the

carrying capacity

of

streams and channels is rapidly exceeded, usually within

hours, resulting in sometimes life-threatening flooding. It

is estimated that the average death toll in the United States

exceeds 200 per year as a result of flash flooding. Many

government weather services provide the public with flash

flood watches and warnings to prevent loss of life. Many

flash floods occur as the result of afternoon and evening

thundershowers which produce rainfall intensities ranging

from a few tenths of an inch per hour to several inches per

hour. In some highly developed urban areas, the risk of flash

flooding has increased over time as the native vegetation

and soils have been replaced by buildings and pavement

which produce much higher amounts of surface runoff. In

addition, the increased usage of parks and recreational facili-

ties which lie along stream and river channels has exposed

the public to greater risk. See also Urban runoff

[Mark W. Seeley]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Battan, L. J. Weather In Your Life. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman, 1983.

Critchfield, H. J. General Climatology. 4th ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Pren-

tice-Hall, 1983.

Floodplain

An area that has been built up by stream deposition, generally

represented by the main

drainage

channel of a

watershed

,

is called a floodplain. This area, usually relatively flat with

respect to the surrounding landscape, is subject to periodic

flooding

, with

return periods ranging from one year to 100 years.

Floodplains vary widely in size, depending on the area of

the drainage basin with which they are associated. The soils

in floodplains are often dark and fertile, representing material

lost the to erosive forces of heavy precipitation and

runoff

.

These soils are often farmed, though subject to the risk of

periodic crop losses due to flooding. In some areas, flood-

plains are protected by flood control measures such as reser-

voirs and levees and are used for farming or residential devel-

opment. In other areas, land-use regulations, encroachment

statutes and local building codes often prevent development

on floodplains.

Flora

All forms of plant life that live in a particular geographic

region at a particular time in history. A number of factors

determine the flora in any particular area, including tempera-

ture, sunlight,

soil

, water, and evolutionary history. The

564

flora in any given area is a major factor in determining the

type of

fauna

found in the area. Scientists have divided the

earth’s surface into a number of regions inhabited by distinct

flora. Among these regions are the African-Indian

desert

,

western African

rain forest

, Pacific North American region,

Arctic and Sub-arctic region, and the Amazon.

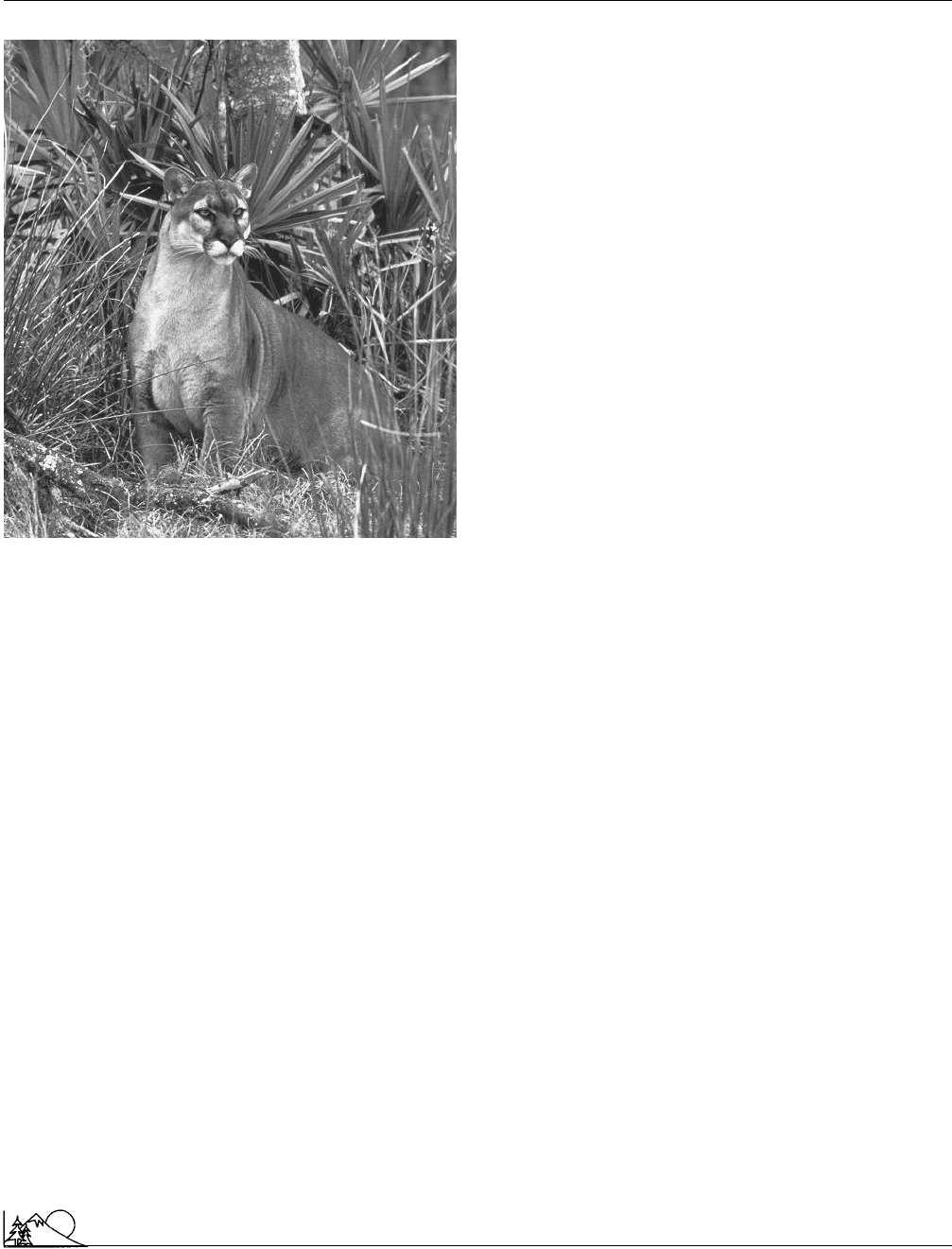

Florida panther

The Florida panther (Felis concolor coryi), a subspecies of the

mountain lion, is a member of the cat family, Felidae, and

is severely threatened with

extinction

. Listed as endangered,

the Florida panther population currently numbers between

30 and 50 individuals. Its former range probably extended

from western Louisiana and Arkansas eastward through

Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, and southwestern South

Carolina to the southern tip of Florida. Today the Florida

panther’s range consists of the Everglades-Big Cypress

Swamp area. The preferred

habitat

for this large cat is

subtropical forests comprised of dense stands of trees, vines,

and shrubs, typically in low, swampy areas.

Several factors have contributed to the decline of the

Florida panther. Historically the most significant factors

have been habitat loss and persecution by humans.

Land

use

patterns have altered the

environment

throughout the

former range of the Florida panther.

With shifts to cattle ranching and agriculture, lands

were drained and developed, and with the altered vegetation

patterns came a change in the prey base for this top carnivore.

The main prey item of the Florida panther is white-tailed deer

(Odocoileus virginianus). Formerly, the spring and summer

rains kept the area wet, and then, as it dried out, fires would

renew the grassy meadows at the forest edges, creating an ideal

habitat for the deer. With development and increased deer

hunting

by humans, the panther’s prey base declined and so

did the number of panthers. Prior to the 1950s, Florida had

a bounty on Florida panthers because the animal was consid-

ered a “threat” to humans and livestock. During the 1950s,

state law protected the dwindling population of panthers. In

1967 the Florida panther was listed by the U. S.

Fish and

Wildlife Service

as an

endangered species

.

Land development is still moving southward in Flor-

ida. With the annual influx of new residents, fruit orchards

being moved south due to recent freezes, and continued

draining and clearing of land, panther habitat continues to

be destroyed. The Florida panther is forced into areas that

are not good habitat for white-tailed deer, and the panthers

are catching armadillos and raccoons for food. The panthers

then become underweight and anemic due to poor nutrition.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Flu pandemic

A Florida panther (

Felis concolor coryi

). (Photo-

graph by Tom and Pat Leeson. Photo Researchers Inc.

Reproduced by permission.)

Development contributes to the Florida panther’s de-

cline in other ways, too. Its range is currently split in half

by the east-west highway known as Alligator Alley. During

peak seasons, over 30,000 vehicles traverse this stretch of

highway daily, and, since 1972, 44 panthers have been killed

by cars, the largest single cause of death for these cats in

recent decades.

Biology is also working against the Florida panther.

Because of the extremely small population size,

inbreeding

of panthers has yielded increased reproductive failures, due

to deformed or infertile sperm. The spread of feline distem-

per

virus

also is a concern to

wildlife

biologists. All these

factors have led officials to develop a recovery plan that

includes a captive breeding program using a small number

of injured animals, as well as a mark and recapture program,

using radio collars, to

inoculate

against disease and track

young panthers with hopes of saving this valuable part of

the biota of south Florida’s

Everglades ecosystem

.

[Eugene C. Beckham]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Belden, R. “The Florida Panther.” Audubon Wildlife Report 1988/1989. San

Diego: Academic Press, 1988.

565

Fergus, Charles. Swamp Screamer: At Large with the Florida Panther. New

York: North Point Press, 1996.

Miller, S. D., and D. D. Everett, eds. Cats of the World: Biology, Conservation,

and Management. Washington, DC: National Wildlife Federation, 1986.

O

THER

Florida Panther Net. [cited May 2002]. <http://www.panther.state.fl.us>.

Florida Panther Society. [cited May 2002]. <http://www.atlantic.net/~oldfla/

panther/panther.html>.

Flotation

An operation in which submerged materials are floated, by

means of air bubbles, to the surface of a water and removed.

Bubbles are generated through a system called dissolved air

flotation (DAF), which is capable of producing clouds of

very fine, very small bubbles. A large number of small-sized

bubbles is generally most efficient for removing material

from water.

This process is commonly used in

wastewater

treat-

ment and by industries, but not in

water treatment

. For

example, the mining industry uses flotation to concentrate

fine ore particles, and flotation has been used to concentrate

uranium

from sea water. It is commonly used to thicken

the sludges and to remove grease and oil at wastewater

treatment plants. The textile industry often uses flotation

to treat process waters resulting from dyeing operations.

Flotation might also be used to remove surfactants. Materials

that are denser than water or that dissolve well in water

are poor candidates for flotation. Flotation should not be

confused with foam separation, a process in which surfac-

tants are added to create a foam that affects the removal or

concentration of some other material.

Flu pandemic

The influenza outbreak of 1918–1919 carried off between

20 to 40 million people worldwide. The Spanish flu outbreak

differed significantly from other influenza (flu) epidemics.

It was much more lethal, and it killed a high proportion of

otherwise healthy adults. Most flu outbreaks kill only the

very young, the elderly, and people with weakened immune

systems. Scientists and public health officials have been try-

ing to learn more about Spanish flu in the hopes of pre-

venting a similar outbreak.

The Spanish flu

virus

caused one of the worst pan-

demic of an infectious disease ever recorded. And while the

threat of many infectious diseases, including tuberculosis and

smallpox, have been contained by antibiotics and vaccination

programs, influenza remains a difficult disease. There are

worldwide outbreaks of influenza every year, and the flu

typically reaches pandemic proportions (lethally afflicting an

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Flu pandemic

unusually high portion of the population) every 10–40 years.

The last influenza pandemic was the Hong Kong flu of

1968–69, which caused 700,000 deaths worldwide, and

killed 33,000 Americans. The influenza virus is highly muta-

ble, so each year’s flu outbreak presents the human body

with a slightly different virus. Because of this, people do not

build an immunity to influenza. Vaccines are successful in

protecting people against influenza, but vaccine manufactur-

ers must prepare a new batch each year, based on their

best supposition of which particular virus will spread. Most

influenza viruses originate in China, and doctors, scientists,

and public health officials closely monitor flu cases there

in order to make the appropriate vaccine. The two main

organizations tracking influenza are the Centers for Disease

Control (CDC) and the World Health Organization

(WHO). The CDC and other government agencies have

been preparing for a flu pandemic on the level of Spanish

flu since the early 1990s.

Spanish flu did not originate in Spain, but presumably

in Kansas, where the first case was recorded in March, 1918,

at the army base Camp Funston. It quickly spread across

the United States, and then to Europe with American sol-

diers who were fighting in the last months of World War

I. Infected ships brought the outbreak to India, New

Zealand, and Alaska. Spanish flu killed quickly. People often

died within 48 hours of first feeling symptoms. The disease

afflicted the lungs, and caused the tiny air sacs, called alveoli,

to fill with fluid. Victims were soon starved of oxygen, and

sometimes effectively drowned on the fluid clogging their

lungs. Children and old people recovered from the Spanish

flu at a much higher rate than young adults. In the United

States, the death rate from Spanish flu was several times

higher for men aged 25–29 than for men in their seventies.

Social conditions at the time probably contributed to

the remarkable power of the disease. The flu struck just at

the end of World War I, when thousands of soldiers were

moving from America to Europe and across that continent.

In a peaceful time, sick people may have gone home to bed,

and thus passed the disease only to their immediate family.

But in 1918, men with the virus were packed in already

crowded hospitals and troop ships. The unrest and devasta-

tion left by the war probably hastened the spread of Spanish

flu. So it is possible that if a similarly virulent virus were to

arise again soon, it would not be quite as destructive.

Researchers are concerned about a return of Spanish

flu because little is known about what made it so virulent.

The flu virus was not isolated until 1933, and since then,

there have been several efforts to collect and study the 1918

virus by exhuming graves in Alaska and Norway, where

bodies were preserved in permanently frozen ground. In

1997, a Canadian researcher, Kirsty Duncan, was able to

extract tissue samples from the corpses of seven miners who

566

had died of Spanish flu in October 1918 and were buried

in frozen ground on a tiny island off Norway. Duncan’s

work allowed scientists at several laboratories around the

world to do genetic work on the Spanish flu virus. But by

2002, there was still no conclusive agreement on what was

so different about the 1918 virus.

The influenza virus is believed to originate in migratory

water fowl, particularly ducks. Ducks carry influenza viruses

without becoming ill. They excrete the virus in their feces.

When their feces collect in water, other animals can become

infected. Domestic turkeys and chickens can easily become

infected with influenza virus borne by wild ducks. But most

avian (bird-borne) influenza does not pass to humans, or if

it does, is not particularly virulent. But other mammals too

can pick up influenza from either wild birds or domestic fowl.

Whales

,

seals

, ferrets, horses, and pigs are all susceptible to

bird-borne viruses. When the virus moves between

species

,

it may mutate. Human influenza viruses most likely pass

from ducks to pigs to humans. The 1918 virus may have

been a particularly unusual combination of avian and swine

virus, to which humans were unusually vulnerable.

Enacting controls on pig and poultry farms may be

an important way to prevent the rise of a new influenza

pandemic. Some influenza researchers recommend that pigs

and domestic ducks and chickens not be raised together.

Separating pigs and fowl at live markets may also be a sensible

precaution. With the concentration of poultry and pigs at

huge “factory” farms, it is important for farmers, veterinari-

ans, and public health officials to monitor for influenza. A flu

outbreak among chickens in Hong Kong in 1997 eventually

killed six people, but the epidemic was stopped by the quick

slaughter of millions of chickens in the area. Any action to

control flu of course must be an international effort, since

the virus moves rapidly without respect to national borders.

[Angela Woodward]

R

ESOURCES

P

ERIODICALS

Gladwell, Malcolm. “The Dead Zone.” New Yorker (September 29, 1997):

52–65.

Henderson, C. W. “Spanish Flu Victims Hold Clues to Fight Virus.”

Vaccine Weekly (November 29, 1999/December 6, 1999): 10.

Koehler, Christopher S. W. “Zeroing in on Zoonoses.” Modern Drug Dis-

covery 8, no. 4 (August 2001): 44–50.

Lauteret, Ronald L. “A Short History of a Tragedy” Alaska (November

1999): 21–23.

Pickrell, John. “Killer Flu with a Human-Pig Pedigree?” Science 292 (May

11, 2001): 1041.

Shalala, Donna E. “Collaboration in the Fight Against Infectious Diseases.”

Emerging Infectious Diseases 4, no. 3 (July/September 1998): 354.

Webster, Robert G. “Influenza: An Emerging Disease.” Emerging Infectious

Diseases 4, no. 3 (July-September 1998).