Fattah H., Caso F. A Brief History Of Iraq

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF IRAQ

142

1830s, a combination of the plague, the fl ooding of the Tigris, and an

Ottoman army at the gates of Baghdad brought down the last of the

Mamluks, Dawud Pasha. A short time later, the Jalilis of Mosul were

also dislodged, as were the Babans of Shahrizor (ca. 1850). Henceforth,

Istanbul sent a steady stream of governors to reclaim the provinces of

Iraq. The history of the mid-19th century onward in Iraq is largely that

of the interaction between a centralizing state and a society still autono-

mous in its philosophy and traditions.

This period in Ottoman history is characterized by a series of

Western-infl uenced reforms, prompted by edicts called tanzimat (“reg-

ulations,” in Turkish) that were promulgated in 1839 and 1859. New

standing armies were raised; land laws went into effect reorganizing

land tenure, production, and revenue; a new administrative map was

created that reordered provinces on a more “effi cient” basis; and local

municipal governments were reorganized to include previously mar-

ginalized groups, such as Christians, Jews, and other minorities. It

has often been stated, somewhat incorrectly, that as a result of these

provisions, the provinces of the Ottoman Empire underwent a process

of rapid “modernization.” The Tanzimat era is generally seen as the

period in which reforms associated with European modernity were

adapted and applied, fi rst, to Istanbul and its surrounding region and,

later on, to both European and Arab provinces of the Ottoman Empire.

But, as many recent studies have shown, this so-called Westernization

was often only a gloss on ongoing, internal developments within the

empire itself. Much of the “new” thinking was not so much the result

of an overt application of European models but a continuous sifting of

different paradigms to reshape a state and society in the throes of an

internal transformation.

The Reform of the Army

The principal reform associated with the Tanzimat era was the reor-

ganization and reconstruction of the army. Internal transformation

had been the rallying cry of Ottoman reformers for quite some time.

Prior to the early 19th century, the Ottoman army consisted of impe-

rial troops, the bulk of which were Janissary regiments. The latter had

infi ltrated the trade and industry of Istanbul as well as the European

and Arab provinces, creating local alliances that often ran counter

to the wishes of the central government that they were supposed to

serve and obey. On a couple of occasions, the Janissaries had even

staged coups and dislodged the sultan himself. The Janissary threat

143

IMPERIAL ADMINISTRATION, LOCAL RULE, AND OTTOMAN RECENTRALIZATION

had become so great that their doom seemed almost foretold; when

Sultan Mahmud II extinguished them through wholesale slaughter,

he signaled the rise of a more centralized military force completely

under his command.

This new force, the Ottoman standing army, was trained and advised

by Westerners, who founded new military schools and pushed for

European arms, tactics, and strategy (Inalcik and Quataert 1994, 766).

While it took almost half a century to materialize, a tighter, leaner army

was established that went on to win several major battles in the early

phases of World War I.

In the provinces of Iraq, the army was reorganized, and new

military and civilian schools were established as a result; the latter’s

emphasis on languages and the hard sciences was somewhat of a radi-

cal departure from the traditional kuttab, or Islamic school, stress on

religious and literary subjects and rote learning. But here again, the

core principles of army discipline, effective training, and loyalty to

the corps took a long time to materialize. In the last quarter of the

19th century, the Sixth Army, based in Baghdad, was considered to be

one of the empire’s least successful military units (Longrigg 1953, 38)

simply because there was never enough money or matériel to hold it

together. Composed of two divisions of infantry, a cavalry division,

and artillery regiments, the army was made up of conscripts, many

of whom could buy their way out of service through a military “tax.”

Entire sectors of Iraqi society escaped the military in this way, while

those soldiers who remained were often unruly and spelled trouble

for the army command.

In 1910–11, however, a strong governor in Baghdad, Nazim Pasha

(1848–1912), who had also been named the commander of the army,

attempted to whip the army into shape. Nazim Pasha’s zeal in reforming

the Sixth Army awakened British alarm. His emphasis that no expense

be spared in this attempt to turn the ramshackle army into a fi ghting

force made him a competitor to watch. Meanwhile, the British consul

received disturbing reports of huge guns being brought in to revital-

ize Ottoman defenses and the daily and nightly training of troops. To

top it all off, Nazim Pasha embarked on furious campaigns against the

Iraqi tribes, creating much dissension in Baghdad, particularly since

he attempted to defeat the tribes in one fell swoop, strongly testing his

unprepared troops. Eventually, he was recalled to Istanbul because of

heavy British pressure. Still, Iraq’s Sixth Army performed very well in

World War I, infl icting a huge defeat on the British in Kut in 1916, only

to be routed at the end of the war.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF IRAQ

144

Local Government Councils, Schools,

New Printing Presses, and Newspapers

Prior to the mid-19th century, no local governing councils had existed

in Iraq outside the shaykh’s tent or the Ottoman governor’s palace.

After the Tanzimat edicts, an administrative council was established

for each provincial capital. Headed by the vali, or provincial governor,

it grouped appointed and elected members; for the fi rst time, the lat-

ter consisted of Christians and Jews. Side by side with administrative

reforms, civilian schools were created that taught a different curricu-

lum, including military training, and followed novel philosophies. By

introducing military training at an early stage and incorporating the

hard sciences, geography, and foreign languages in its curriculum, the

rushdiya (middle school) and idadiya (high school) school system in

Iraq opened up different avenues for its student population.

Under Midhat Pasha (r. 1869–71), the fi rst printing press was intro-

duced in Iraq. This made possible the fi rst state newspaper, al-Zawra,

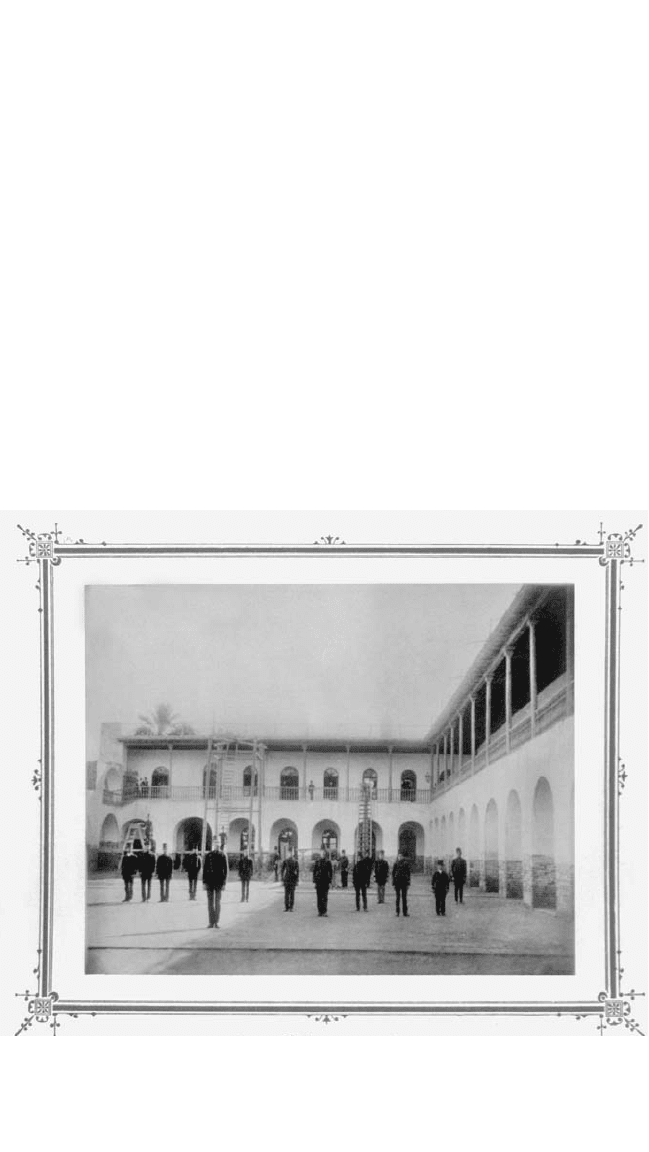

Courtyard of the palace of the Ottoman governor of Baghdad in the late 19th century, dur-

ing the period when the Tanzimat edicts had gone into effect

(Library of Congress)

145

IMPERIAL ADMINISTRATION, LOCAL RULE, AND OTTOMAN RECENTRALIZATION

which was originally published in Ottoman Turkish but was later

turned into a bilingual edition. Among its many editors was the sober

Islamist intellectual Shaykh Mahmud Shukri al-Alusi (1857–1934),

whose great reputation as a reformist scholar endowed the newspaper

with a crusading ethos. Among his many editorials were those that

castigated late Ottoman authorities for neglecting Islamic places of

worship and pious foundations.

Forty years later, under less stringent censorship rules (brought

on by the Constitutional Revolution in Turkey in 1908), a number of

Iraqi as well as foreign-owned papers made their appearance. About

36 papers and magazines were published in Iraq by Iraqis before the

collapse of the Ottoman Empire in 1918. For example, the outstand-

ing weekly al-Riyadh began publication in 1910. Owned by Suleyman

al-Dakhil, who is considered to be the fi rst journalist-editor from Najd

(central Arabia) to own and publish a newspaper, it was put together

in Baghdad, due in no small part to the fact that Arabia and Iraq had

long been linked by cultural, economic, and social ties. Although it

only lasted four years, al-Riyadh published original and path-break-

ing reports on central Arabian tribes and dynasties and courted the

Ottomans by openly appealing to them to intervene against British

schemes in the Arabian Peninsula.

Al-Riyadh was only one of the many newspapers published at the

turn of the 20th century. Other Iraqi-owned newspapers of note were

al-Raqib, published by the crusading journalist Abdul-Latif Thunayan,

and Sada Babil, owned and operated by the Christian intellectuals

Dawud Sliwu and Yusif Ghanima. Echoes of those papers continue

today. For instance, al-Nahda was established by Ibrahim Hilmi Umar

and Muzahim Amin al-Pachachi in 1913. Al-Nahda lives on today

because al-Pachachi’s son, Dr. Adnan al-Pachachi, established a paper

under the same name in 2003. (It was one of the most sober and well-

researched papers published in Baghdad after 2003.)

The Land Law of 1858

Under the Ottomans, the area of south-central Iraq, known in Islamic

history as al-Sawad, had become the home of many displaced tribes of

Najdi origin, such as the Shammar and the Bani Lam, who had migrated

from Arabia to Iraq from as early as the 17th century. Throughout the

18th to the last part of the 19th centuries, Ottoman governors tried

several different strategies to tame the nomadic and semipastoralist

tribes. Because the usual tactics of attacking tribal camps and sup-

A BRIEF HISTORY OF IRAQ

146

pressing select tribal leaders proved to be short-lived policies, Ottoman

pashas and military commanders were eventually drawn to the strategy

of tribal settlement on collectively held tribal lands. The notion was

that sedentarization would produce stability, and stability would equal

peace and prosperity.

The story of reform is usually associated with the arrival in Baghdad

of the vali, or governor, Midhat Pasha in 1869. However, even earlier

reformist valis introduced, for example, river steamers in 1855 (preced-

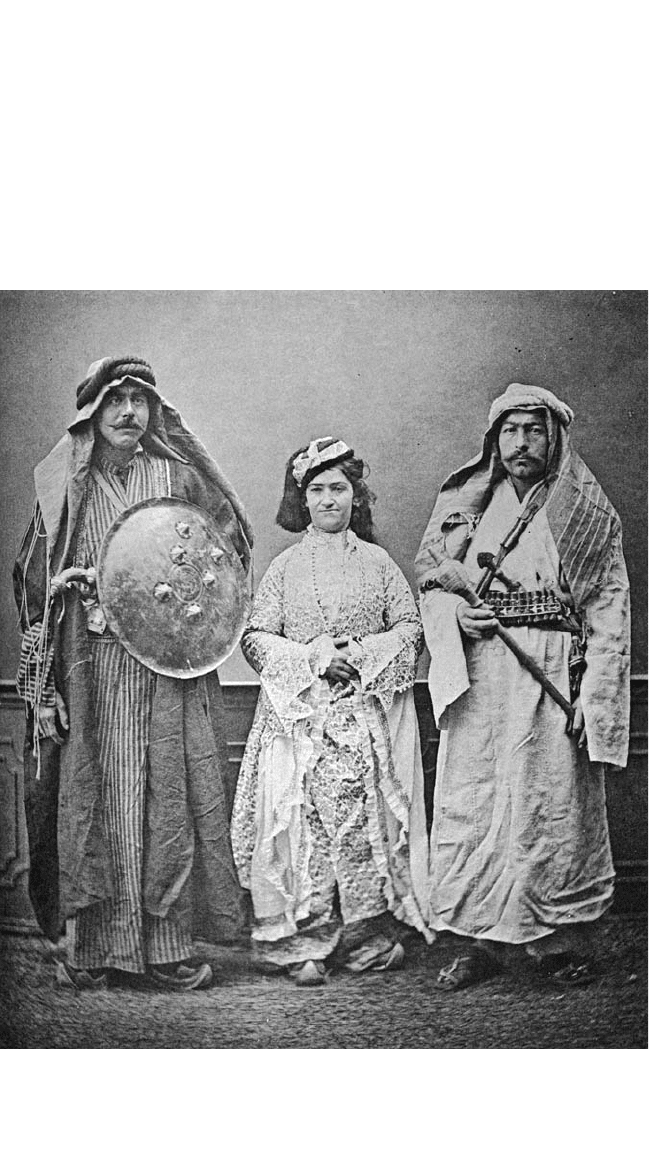

Arabs from Baghdad Province in traditional clothing. The man on the left (with shield) is

wearing traditional Shammar clothing.

(Library of Congress)

147

IMPERIAL ADMINISTRATION, LOCAL RULE, AND OTTOMAN RECENTRALIZATION

ing those of British fi rms) and augmented the fl eet in 1869. Evidence

also suggests that governors had already begun reviewing and attempt-

ing to overhaul the land system in Iraq before Midhat’s arrival. With his

accession to power in Iraq, however, the review and overhaul began in

earnest.

Iraqi governments in Baghdad, Basra, and, to a lesser extent, Mosul

faced large problems with regard to the agricultural sector throughout

the 18th and early 19th centuries. First was the problem of the insta-

bility of revenue collection; although tribal lands were theoretically

administered for the collective benefi t of the tribe, the paramount

shaykh had wide latitude in the use and disbursement of agricultural

revenue. Throughout the period in question, tribal shaykhs were some-

times patronized by the state but more often warred upon. This was

because in order to secure revenue for the state, either the shaykh paid

out taxes willingly or was forced to do so through military coercion.

Because of the erratic nature of revenue collection, therefore, the state

never became truly solvent.

A second problem, alluded to earlier, was the fact that by the middle

of the 18th century, “whatever the formal title of the land—miri [state

lands], mulk [land privately owned], or waqf [endowments]—much of

it was in fact under private control [and] much of the miri-land was

treated as the private property of high offi cials or of members of infl u-

ential families” (Nieuwenhuis 1982, 112–113). Thus, the second factor

inhibiting the state’s economic well-being was the permanent alienation

of lands formally under state title. As a result of these two factors, both

of which undercut the state’s income, government reform of land tenure

and production became an urgent proposition.

Midhat Pasha’s fi rst act was “to replace the piecemeal policies of his

predecessors with a program of land registration and tax reform which,

he hoped, would increase production, encourage nomadic settlement,

raise revenues, and destroy the power of the tax farmers and tribal

sheikhs all in one go” (Owen 1981, 185). The goal of the Land Law,

promulgated in 1858 in Istanbul but applied only much later in Iraq,

was to secure the land for those who actually cultivated it, but the tribal

peasants for whom it was legislated attached no importance to private

property and the greater majority even suspected that land registration

schemes were a government ploy intended to list conscripts for the new

army. Many shaykhs and urban merchants were more perspicacious,

however, and registered formerly communal lands under their own

names; after Midhat’s departure in 1871, some sanads, or title deeds,

were even auctioned off to the paramount shaykh’s own family and

A BRIEF HISTORY OF IRAQ

148

allies (this happened in the Muntafi q districts of south-central Iraq),

reversing Midhat’s original intent to reward the cultivator and not his

patron with title deeds.

Land registration failed its original constituency because it was

undertaken with little cognizance of the facts on the ground; the idea

that lands were communally held yet subject to the infl uence of the

paramount shaykh was not something that had been anticipated in the

law. Moreover, as time went on, the whole registration scheme became

politicized; because registration brought with it economic power, the

local governments began to use it in ways to further their political

agendas. Thus, they awarded title deeds to tribal leaders who did their

bidding, and disenfranchised those with whom they had complaints.

Also, the drawing of new borders around tribal districts by administra-

tive fi at caused turmoil in the districts themselves; so many title deeds

were sloppily recorded that they became the cause for litigation later

on. But perhaps the most important development of the new reorder-

ing of land and property ownership in late 19th-century Iraq was the

rise of a new landed class of tribal shaykhs and urban merchants and

moneylenders. This last, loosely defi ned strata was to become the new

elite of the early 20th century, with whom the Ottomans and, later on,

the British had to deal and, more important, placate at various critical

junctures of the country’s history.

Trade and Transport: The British Dimension in Local Affairs

The Tanzimat reforms were not the only factors to reshape Iraq in the

19th century. By the 1830s, a number of developments, both internal

and external, had combined to radically affect Iraqi trade. In 1811–12,

the Ottoman-Egyptian army under Ibrahim Pasha, son of the viceroy

of Egypt, Muhammad Ali, had begun its Arabian campaign; eventually,

it was to defeat the remnants of the once powerful Saudi state that had

kept much of the Gulf, Arabia, and southern Iraq in its thrall. No lon-

ger threatened by the Saudi monopoly on regional trade, whether on

land or by sea, merchants from the area were able to jump back into

the fray, their networks revitalized, their prospects bright. In the early

1830s, however, the British had begun to make important inroads in

the Gulf region. After the 1821 truce with the local principalities on

the Arab side of the Gulf and their even more assured control of the sea

route to India, the British became the unchallenged masters of Indian

Ocean trade. Henceforth, regional merchants, whether Indian, Persian,

or Arab, had to tread softly with the new power in their region; as a

149

IMPERIAL ADMINISTRATION, LOCAL RULE, AND OTTOMAN RECENTRALIZATION

result of this new state of affairs, the more clever merchants made their

peace early with the British presence in Iraq and the Gulf and became

mediators between the latter and local society.

In Iraq proper, this meant that although foreign trade became the

chief monopoly of British ships and British-affi liated merchants, local

trade—the trade carried on in small boats on the twin rivers and camel

caravan in the interior—remained under local hands. This made for a

risky enterprise for the British. The British shipping company of Lynch

Bros., for example, fi nally introduced its two steamers on the Tigris

in 1862–65 but required the services of a soldier to make the journey

from Baghdad to Basra, and from there to Bombay, in complete secu-

rity. Still, a small but gradual increase in Iraq’s seaborne trade to India

occurred at that time, and Iraqi goods—dates, wheat, barley, and even

live horses—were transported in greater numbers to India and Europe.

It was only with the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, however, that

there was an exponential growth in Iraqi trade. From 1870 to 1880, for

instance, the value of exports rose from £206,000 to £1,275,000 (Owen

1981, 182).

Between 1900 and 1913, Britain accounted for nearly half of Iraq’s

imports and a quarter of its exports (Owen 1981, 276). Based on the

tonnage of ships alone, it was also by far the most important shipping

power in the Gulf and Indian Ocean, reaching 137,000 tons a year,

whereas local craft only carried 12,500 tons. Finally, it is calculated that

in 1913, 163 British steamers arrived yearly in Iraq (Owen 1981, 276).

This raft of fi gures would be impressive on its own were it not for the

fact that British supremacy was not only based on commercial power

but on military infl uence as well. By 1914, at the start of World War I,

Britain was the most important naval power in the world, a fact under-

lined in the Gulf and Iraq by its unstated supremacy on these shores.

The Shii Shrine Cities of Iraq Revisited

At the beginning of the 19th century, the Shii shrine cities of Najaf,

Karbala, and Kadhimain continued under the spiritual infl uence of reli-

gious scholars, the maraji al-taqlid (marja al-taqlid, sing., “the source

of emulation”; a religious leader of such erudition that individual Shiis

follows his teachings), or the mujtahids (Islamic legal authorities). But

beginning in or around the 1780s, changes had occurred in Najaf and

Karbala that brought external infl uence to bear on the cities’ social,

economic, and political composition. The fi rst had to do with what has

been called the remission of “Indian money” to the shrines, especially

A BRIEF HISTORY OF IRAQ

150

those in Najaf and Karbala. Briefl y, the Oudh Bequest, set up by the

Shiis ruler of Awadh (Oudh) in British-controlled India, channeled

close to £10,000 a year to the leading Shii clergy in Iraq. Spent on badly

needed infrastructural projects, such as canal building and irrigation

works, as well as for money contributions to the leading mujtahids,

the bequest cemented ties between Najaf, Karbala, and northern India.

After the British annexation of Awadh in 1856, when the bequest

began to be distributed by the British agent in Baghdad on behalf of

the nawab of Awadh, it further shored up ties between the shrine cities

and the British. However, because of the complicated situation of the

Shii cities, in which autonomy movements were played out against the

background of imperial Ottoman centralizing rule and rival Persian and

Indian infl uences, little concrete change was affected between the Shii

leadership and British economic and political interests in Iraq.

The second change occurred with the imposition of a more central-

ized administration in Karbala. Up to the early 20th century, all of the

shrine cities of Iraq were in theory administered by Ottoman governors

and tax collectors and kept in check by Ottoman troops. By the 1820s

and 1830s, however, the localization of power had affected more than

the religious clergy; it had brought about the emergence of a class

within a class of merchants and city “bosses” who had usurped power

from the older landholding families and begun to control the city’s

wards. This “mafi a” (to use Juan Cole’s terminology) consisted of youth

gangs, small merchants, and laborers, with the occasional vagabond

journeyman or thief thrown in.

The unique status of Karbala, with its self-governing hierarchy of

clergy, landholders, and urban gang leaders, irked the Ottomans. After

repeated military feints against the city, which had become dangerously

independent in Ottoman eyes, the governor of Baghdad, Najib Pasha,

sent an army to conquer Karbala and bring it back within the Ottoman

fold. In January 1842, the die was cast. Breaching a strategic wall of

the city, the Ottoman army attacked. After a fi erce fi ght in which more

than 5,000 of Karbala’s forces were killed while only 400 government

soldiers lost their lives, the Ottoman troops succeeded in reining in the

local elements and conquering the town and its environs. On January

18, Najib Pasha entered Karbala and made straight for the sanctu-

ary of Imam Husayn, where he and his military commanders prayed

and gave thanks. After that, the governor spelled out the dimensions

of Karbala’s defeat: A Sunni governor was appointed over Karbala,

Sunni judges were sent to the city to administer the court system, and

a Sunni preacher was brought in to lead the Friday prayers, at which

151

IMPERIAL ADMINISTRATION, LOCAL RULE, AND OTTOMAN RECENTRALIZATION

the Ottoman sultan’s name would be ritually mentioned as a symbol of

dominion (Cole 2002, 118).

While Karbala’s fi re was extinguished and its spirit broken, the struc-

ture of Ottoman power remained a facade. By the early 20th century,

all the city’s powerbrokers—the local mob leaders, smaller clergy, and

merchants—had returned to assume their places in the great game of

autonomous rule versus renewed imperialism in the context of late

Ottoman Iraq.

Conclusion

By the turn of the 20th century, the Iraqi provinces had become more

closely linked under late Ottoman rule. While the greater incorpora-

tion of the provinces into a more tightly centralized and demarcated

region brought with it closer identifi cation with the notion of “Iraq”

as a common homeland, the country’s population was not uniformly

Ottomanized as a corollary of that identifi cation. Certain elites emerged

that recognized their affi liation with the greater empire, but they did

so on a vastly different basis than before. The starting point for the

reinforced ties between the provinces and the center was now based

on a revised interpretation of what it meant to be an Ottoman citizen.

No longer seen as subjects but as full-fl edged members in a pluralis-

tic Islamic empire, some Iraqis took up a wider Ottoman affi liation

because it promised a fairer deal between equal citizens in the greater

Ottoman realm. The ideology of Ottoman citizenship also tied in to the

greater representation of national, ethnic, and religious minorities in

the empire, particularly Christians and Jews, a factor that initially may

have inhibited the wholesale adoption of an “Osmanli” nationality by

its Arab-Muslim adherents.

Although reformist valis had successfully begun to implement ideas

that would radically restructure the provinces, those ideas required

time to fall into place. Even so, several reforms had begun to impact

the country in the latter years of Ottoman rule. First were the military

reforms that reorganized the Sixth Army and made it a competent

fi ghting force capable not only of defending the country but of instigat-

ing well-planned offensives in wartime. Second, military and civilian

schools had begun to cut into the huge illiteracy rate; the most prom-

ising military cadets were given scholarships to join the military and

administrative colleges in Istanbul. Many of them returned as avowed

Turkophiles. Third, with the introduction of the fi rst offi cial newspaper

in Iraq, al-Zawra in 1869, the fl oodgates of newspaper and magazine