Gardiner V., Matthews H. The changing geography of the United Kingdom

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

IAN BOWLER

96

cent of all laying hens. Other enterprises, and other parts of the UK, have experienced

lower levels of concentration: in Wales, for example, the 14 per cent of largest producers

farm only 46 per cent of the beef cows.

On specialisation, the broad regional contrasts of specialisation in crop and livestock

production remain from the productionist era, with only changes in detail. Under the

increasingly competitive market conditions of the 1990s, and in common with producers

in other EU states, individual farm businesses in the UK have continued to obtain economies

of scale by specialising in a limited number of farm products. Taking some examples

from crop farming, and comparing the mid-1970s (Bowler 1982) with 1996, wheat

production remains localised in the eastern counties of England, with the area of the crop

contracting in north-east Scotland, Somerset and Hampshire (Figure 5.1). Barley, more

widely distributed than wheat throughout England and Scotland, has lost its significance

in most counties in competition with imports of livestock feed, but especially in north-

east Scotland and north-east England. The area of oilseed rape, now concentrated in east-

central England, has increased in Fife and Lothian but has decreased in the Ridings of

Yorkshire and in the East Midlands.

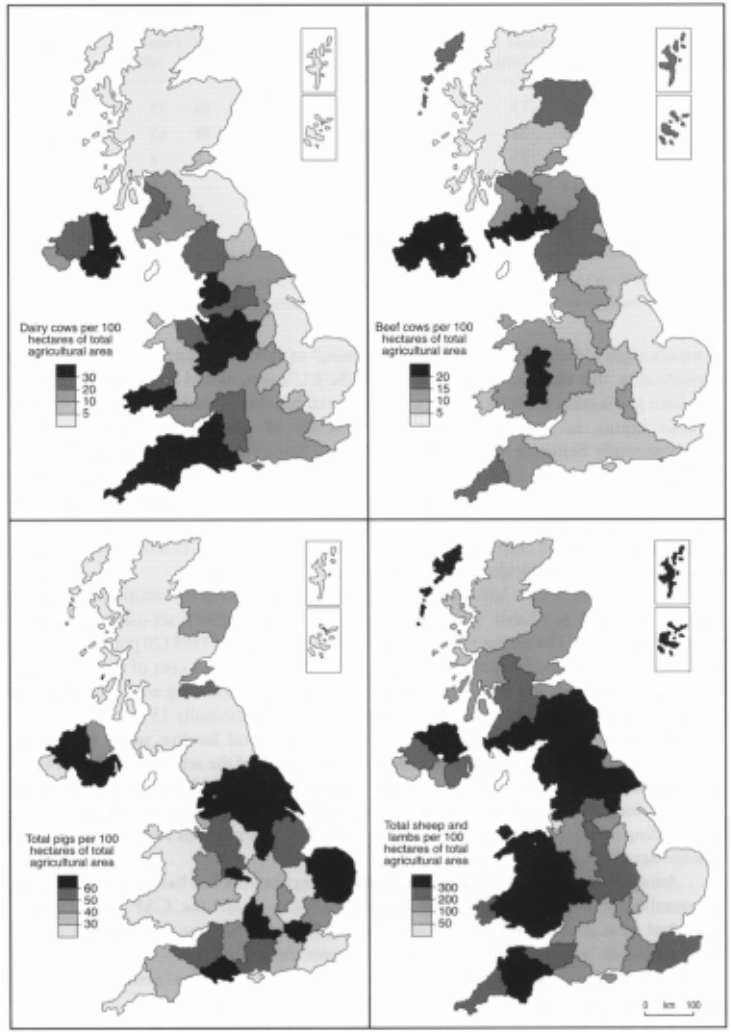

Similarly, regional differences in specialisation in livestock farming have continued

(Figure 5.2). Market trading in milk quotas, for example, has continued the relocation

of dairying into western parts of the UK under the forces of comparative economic

advantage, especially to the benefit of Northern Ireland, Cheshire and counties in south-

west England. During 1995/6, for example, Northern Ireland became a net gainer of

85.7 million litres of purchased quota (mainly the counties of Down and Tyrone), whereas

England suffered a net loss of 41.7 million litres (mainly West Yorkshire, Norfolk and

the West Midlands). Beef cows, although widely distributed throughout the UK, remain

most localised in Northern Ireland, the Scottish Borders and central Wales, but with

numbers reduced by the late-1990s under the slaughter programme designed to eliminate

BSE from the food chain. Sheep densities remain highest throughout Wales and northern

England, Devon and west-central Scotland; but production has spread out into the

lowlands, partly to compensate for the reduction in dairying but mainly to meet the

demand for sheepmeat on the EU market. Specialised areas of pig production have

been further consolidated in the Ridings of Yorkshire, and in Lancashire, East Anglia,

Fife, Lothian and Armagh (Figure 5.2).

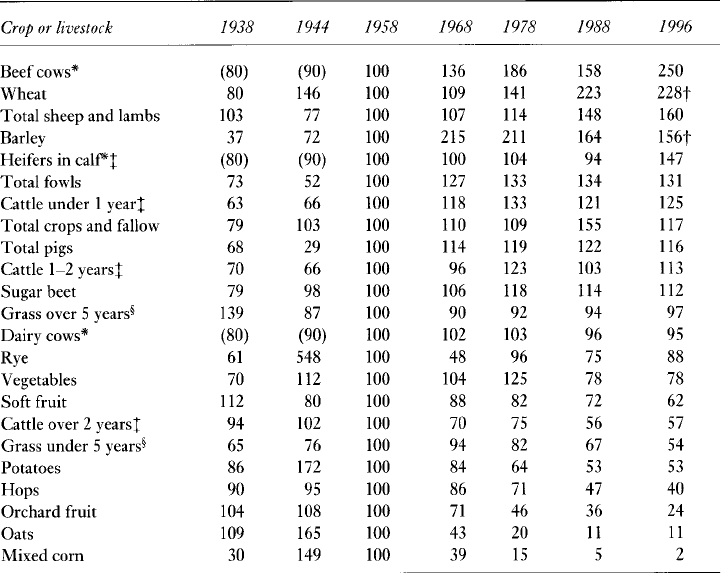

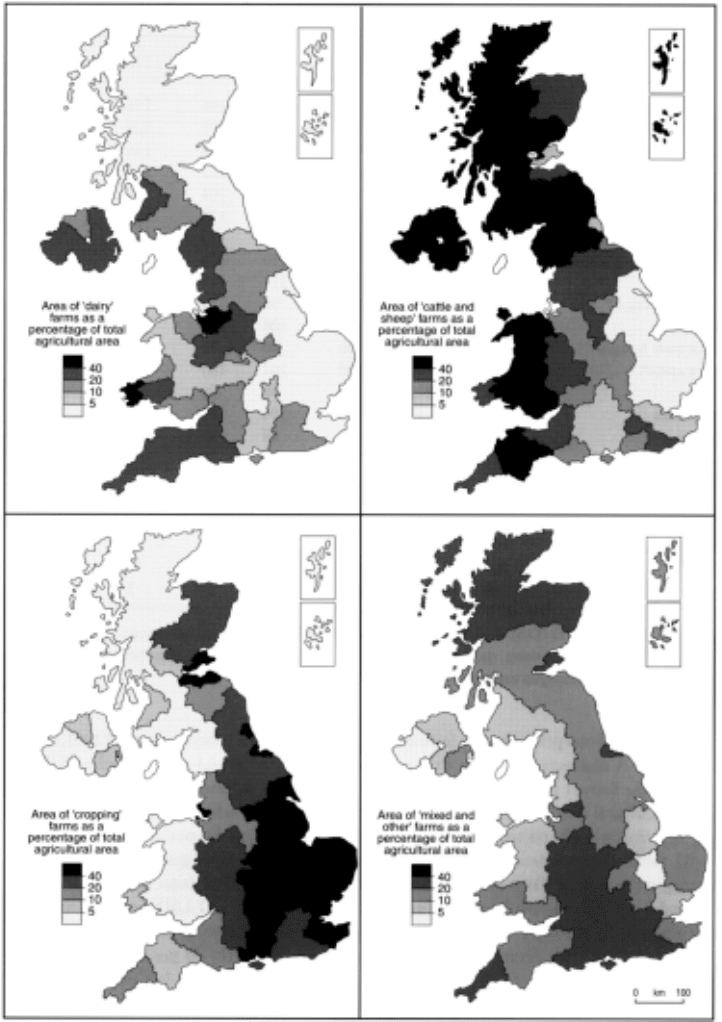

Table 5.11 and Figure 5.3 summarise the impacts of these recent adjustments in UK

agriculture as regards farm-type structure. For example, the number and proportion of

specialist dairy farms declined between 1975 and 1996, with compensating gains in the

proportion of cattle and sheep farms. The latter now dominate the type of farm structure in

western counties of the UK, from Cornwall and Devon in the south-west, through Wales

and Northern Ireland, to northern England and Scotland. The proportion of cropping farms

increased slightly, to the advantage of most counties in east and central England; whereas

the relative importance of horticulture and pig and poultry farms declined, mainly through

competition with low-cost imports from other countries both inside and outside the EU.

Portents of post-productionism

Despite the continuation of many features of productionist agriculture, a number of post-

productionist trends can be identified in UK agriculture and summarised using the terms

AGRICULTURE

97

FIGURE 5.2 Regional distribution of selected livestock, 1996

Sources: Agricultural Statistics, MAFF; SOAFD; DANI; WO.

IAN BOWLER

98

‘extensification’, ‘diversification’ and the ‘greening’ of farming practices. Looking first at

extensification, this tendency is consistent with the EU’s agricultural objectives of reducing

total farm production while increasing environmental benefits. Evidence is growing of lower

fertiliser inputs to agriculture, partly as a result of grant-aided schemes such as

Environmentally Sensitive Areas (ESA) and Nitrate Sensitive Areas (NSA), and partly as a

result of the economic pressure on farmers to increase the cost-effectiveness and efficiency

of their expenditure on fertilisers. Evidence of reductions in agri-chemicals is less clear

(pesticides comprised 4 per cent of national agricultural expenditure in 1995), but the wider

acceptance of integrated crop management (ICM) practices suggests that the upward growth

in the application of herbicides and pesticides may have been checked.

These developments have been associated with a significant downturn in the area of

cropland in the UK (Table 5.12) as a result of the compulsory set-aside programme introduced

in 1993. The earlier voluntary set-aside programme of 1988 (20 per cent of arable land) had

a very limited impact within the UK: by 1992 only 4 per cent of the 1988 arable area had

been retired, and then mainly in the marginal cereal growing areas of central and southern

England. The 1993 programme, with its rotational (initially 15 per cent of arable land) and

non-rotational (initially 18 per cent of arable land for five years) options, by contrast, has

had a greater impact. The volume and location of the set-aside land follows the prior

distribution of crop farming in the eastern counties of England and Scotland. However, with

80 per cent of the land in rotational set-aside, and the percentage of arable land needing to

be set-aside falling during the 1990s (e.g. 5 per cent in 1998), environmental benefits have

been limited.

Another contribution to the extensification of agriculture has been made by capping

the number of livestock eligible for financial support under the CAP. For example, individual

farm quotas apply to the Sheep Annual Premium Scheme and the Suckler Cow Premium,

while ‘regional ceilings’ apply to payments under the Beef Special Premium and the HLCA.

Restraints have been placed on the expansion of subsidised production through these

measures, including the further over-grazing of upland pastures.

A second feature of post-productionism is the development of diversification in

agriculture; here three dimensions can be identified: farm diversification, other gainful activity

(OGA) and farm woodland. Farm diversification involves the introduction of a new, non-

TABLE 5.11 Type of farm structure in the UK, 1975 and 1996 (per cent full-time farms)*

Source: MAFF/SOAFD/DANI/WO, Digest of Agricultural Census Statistics (various years), HMSO.

Notes: *Definitions vary in detail over time and between counties; †Rounding errors.

AGRICULTURE

99

traditional enterprise into the farm business, resulting in a redeployment of land, labour and

capital. A distinction is often drawn between agricultural and non-agricultural diversification,

the former including new crops or livestock, such as linseed and deer respectively. Non-

agricultural diversification includes enterprises that add value to products on the farm (e.g.

farm-made yoghurts and cheeses), direct marketing (e.g. pick-your-own crops and farm

shops), farm accommodation, recreational activities (e.g. sport fishing and horse livery),

and catering services (e.g. farm restaurants). Farm diversification has been grant-aided in

the UK under the Alternative Land Use and the Rural Economy (ALURE) programme, and

more specifically through the Farm Diversification Grant Scheme (FDGS), between 1988

and 1993. In the UK, diversification has affected approximately 20 per cent of farms but

more so in the urban fringes of large urban centres (for instance, London and Birmingham

where market opportunities exist in serving urban consumers), and in areas favoured by

tourism (for instance, agricultural areas in the south-west and north-east of England). Under

the FDGS, farm tourism was the most important enterprise to be developed, with such

diversification greatest in the north-east, south-east and south-west counties of England.

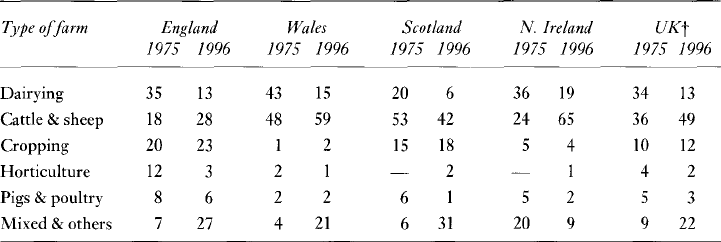

TABLE 5.12 UK agricultural trends in selected crops and livestock, 1938–96 (crop areas or livestock

numbers as per cent of 1958)

Source: MAFF/SOAFD/DANI/WO, Digest of Agricultural Census Statistics (various years), HMSO.

Notes: *Before 1960, beef cows, dairy cows and heifers in calf were collected together; †1997; ‡Dairy

and beef livestock; §Changed census definitions in 1959 and 1975.

IAN BOWLER

100

FIGURE 5.3 Regional distribution of selected types of farming, 1996

Sources: Agricultural Statistics, MAFF; SOAFD; DANI; WO.

AGRICULTURE

101

But the process of farm diversification has been socially selective to the advantage of younger,

better educated and trained farmers, farm families in which farm women have become

involved in managing the farm business, and larger farms where there is greater access to,

and ability to finance, borrowed capital. The increased importance of ‘mixed’ farming in

the type of farm structure of the UK, especially in south and central England (Table 5.11

and Figure 5.3), provides an indication of greater agricultural diversification, although the

category also reflects the introduction of additional but traditional enterprises onto formerly

specialist farms in the 1990s (e.g. beef onto cropping farms or sheep onto dairy farms).

Seeking employment away from the farm (OGA) is increasingly important, partly as

a survival strategy amongst farm families on smaller farms but partly as a means of personal

development or capital accumulation on larger farms. Approximately 24 and 29 per cent of

adult males and females, respectively, in UK farm families appear to be involved in OGA,

together providing a conservative estimate that one-third of farm households have a second

source of earned income. This percentage increases in areas adjacent to urban-based

employment opportunities and in peripheral regions where multiple job holding is a cultural

tradition, for instance in the Highlands of Scotland. Depending on their educational

qualifications and non-farming skills, both men and women gain employment in a wide

range of occupations, varying from jobs in services, factories and offices, through professional

occupations such as teaching and nursing, to management in companies sometimes owned

by the farm family. On almost half of smaller farms, OGA compensates for low farm incomes

and is significant in enabling them to survive as businesses. Indeed on a majority of farms

with OGA, half or more of the family income is generated by off-farm work and forms an

important component of the diversification of agriculture. Nevertheless, it is important to

recognise that nearly half of farmers with OGA have entered agriculture from a non-farming

background, so that taking an off-farm job is more than a survival strategy by ‘traditional’

farm families.

Farm woodland provides the third example of diversification in agriculture. Although

often identified as the main alternative use for ‘surplus’ farmland, farm woodland shows

only a modest and spatially uneven development in the UK over the last decade, despite

financial incentives from the state. For example, grant aid has been available to farmers

for planting, managing, compensating for loss of agricultural income and improving farm

woodland under a succession of schemes, including the 1988 Farm Woodland Scheme

(£10 million from MAFF under ALURE) and the Woodland Grant Scheme (Forestry

Commission), the non-rotational element of the 1988 and 1993 set-aside programmes,

and the 1992 Farm Woodland Premium Scheme (under EU Regulation 2080/92). Entry

into these schemes has been voluntary for participating farmers and has favoured younger,

better-educated farmers in the central counties of England, especially in localities having

a tradition of farm woodland. The limited development of farm woodland is illustrated by

the 14,000 hectares planted out of a target of 36,000 hectares under the 1988 Farm

Woodland Scheme, although most of the trees were broadleaf varieties (oak, ash and

beech). At issue is the setting of grant aid at too low a level to compensate farmers for

‘lost’ agricultural production, the long payback time of the investment, and inexperience

with farming woodland.

The third dimension of post-productionism is the ‘greening’ of farming practices,

and two main features can be identified as regards how farming is practised: the development

of organic farming and farmer response to state-aided agri-environmental schemes. Organic

IAN BOWLER

102

farming implies production without inorganic fertilisers, agri-chemicals and intensive

livestock techniques and it has developed to a lesser extent in the UK compared with

many other European countries. On the one hand, the growth in consumer demand for

organic produce has not been as great as anticipated, despite a number of surveys showing

consumer support for such food. In practice, consumers have been resistant to the price

premium placed on organic farm produce, with multiple retailers in turn proving cautious

in marketing organic produce because of its lower turnover on supermarket shelves. On

the other hand, potential producers have been unsure of the economic returns to be obtained

from organic as compared with conventional crop and livestock production. In addition

there has been an ‘income gap’ during the two-year conversion period from conventional

to organic production, although this has been partly addressed by the Organic Scheme

introduced under the AEP. The marketing problem for producers has been compounded

by retailers importing lower-cost organic produce from other European countries. The

outcome for organic farming in the UK is a concentration of development on small farms

in west Wales, the Vale of Evesham and Sussex, and on larger crop farms scattered

throughout eastern England.

On agri-environmental schemes to stimulate the ‘greening’ of farming practices, the

UK took a lead in the EU in developing the concept of ESA, introduced into the EU in 1985

under Regulation 797/85 (Article 19) and into the UK under the 1986 Agriculture Act. For

England, five ESA were designated in 1986/7 and a further seventeen by 1994. In common

with all agri-environmental schemes to date, participation by farmers has been voluntary,

producing an uneven pattern of involvement. By 1995, ten-year management agreements

had been reached with 7,700 farmers, covering an area of 400,000 hectares. Research in the

ESAs has found that the annual payments to farmers succeed in reducing levels of fertiliser

use, lead to pasture management practices that are more sensitive to wildlife, especially

ground-nesting birds, have little effect on pre-existing livestock densities, but maintain

landscape features such as field barns, walls and hedges. In 1989, the Farm and Conservation

Grant Scheme provided grant aid for capital works on hedges, stone walls, shelter belts,

repairs to traditional buildings and farm waste handling facilities. Also in 1989, a Countryside

Premium (for set-aside land) scheme was introduced into seven counties in eastern England:

this scheme was funded by £13 million over three years from the Department of the

Environment (DoE) and aimed at grant-aiding crop farmers in wildlife and landscape

management. A national Countryside Stewardship (Pilot) Scheme funded by the Countryside

Commission followed in 1991 (upgraded to a full scheme by MAFF in 1996), with grant

aid this time helping farmers (re)create environmental features such as riverside water

meadows, lowland heath, chalk and limestone grassland, moorlands and coastal vegetation

in ‘target landscapes’. By 1996, over 5,000 management agreements were in place at a cost

of £11.7 million each year. A parallel Tir-Cymen Scheme has operated in Wales under the

aegis of the Countryside Council for Wales. The UK has also taken part in the EU’s

programme to reduce goundwater pollution from farm fertilisers (Directive 91/676) through

the designation often (pilot) nitrate sensitive areas (NSA); twenty-two further NSA were

designated in 1994 with financial compensation available to farmers who agreed to change

their farming practices over a five-year period so as to reduce nitrate leaching. Most recently,

grant aid has been provided under the UK’s AEP under titles such as the Habitat Improvement,

Moorland, Organic and Countryside Access Schemes, but with consequences that have yet

to be fully researched. Taking the UK as a whole, these agri-environmental schemes have

AGRICULTURE

103

had only marginal impacts on farming practices and environmental outcomes. As shown by

Battershill and Gilg (1996) and Potter (1997), such impacts are confined to a limited range

of farming areas and individual farms, where pro-conservation attitudes of farmers and a

commitment to ‘traditional’ farming act selectively on farmers participating voluntarily in

the schemes.

Developments in agricultural marketing

An important feature of the third food regime is the further transformation of how food is

marketed to the consumer. Marketing at the farm gate, as well as down the marketing chain,

is being affected by a further tightening of control by non-farm capitals in the food processing

and retailing sectors, and also by an increasing reaction to such control by both farmers and

consumers.

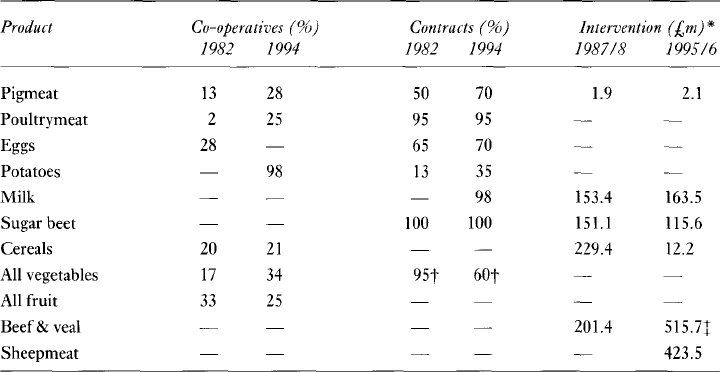

Looking first at the role of the EU, intervention agencies under the CAP still underpin

the market for the main agricultural products. In the UK, the Intervention Board for

Agricultural Produce acts as the agent of the EU by purchasing, storing and subsequently

marketing surplus farm products, often through subsidised exports. Considerable sums of

money are expended, despite a general reduction in price support levels. Whereas expenditure

under the CAP on cereals, and to a lesser extent sugar beet, has fallen considerably under

the revised 1992 pricing arrangements (see pp. 86–7), greatly increased expenditure is evident

in the marketing of sheepmeat and beef/veal (Table 5.13).

The significance of food processors in UK agriculture, as established during the second

food regime, has continued into the 1990s. Most food reaching the consumer is subject to

some form of industrial processing, including washing, grading and packaging. For example,

TABLE 5.13 UK agricultural marketing of selected products through co-operatives, contracts and

CAP intervention, 1982–94

Source: Commission of the European Communities, The Agricultural Situation in the Community—

Report (various years), Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

Notes: *Expenditure by the Intervention Board for Agricultural Produce; †Peas; ‡Non-BSE.

IAN BOWLER

104

until recently the Milk Marketing Board for England and Wales (now Milk Marque Limited)

controlled over 75 per cent of manufacturing capacity for butter and 50 per cent of the

capacity for hard-pressed cheese. In common with other parts of the manufacturing sector,

food processing companies have experienced downsizing and restructuring in recent years;

sectors showing the highest levels of concentration (i.e. fewest competing firms) are

brewing, biscuits, margarine, starch and bread/flour; the least concentrated are animal/

poultry food and vegetable/animal oils and fats. Most companies hold back from direct

ownership of farms, finding it more cost-effective to obtain their raw materials through

forward production contracts placed with a small number of larger producers, including

farmer co-operatives. By the mid-1990s, for example, all sugar beet, 98 per cent of milk,

95 per cent of poultrymeat and 70 per cent of eggs and pigmeat were produced under

contract (Table 5.13). In these circumstances, nearness to the relevant processing factory

has become an important factor in the location of production. At present most UK food

processors obtain their raw materials from domestic producers or from within the EU;

however, the prospective enlargement of the EU could well widen the area over which

UK food processors place their contracts.

By far the most significant development in the marketing of farm products in the

1970s and 1980s, however, was the growth in the economic power of a relatively few but

large multiple retailers through their chains of supermarkets (Wrigley 1987). By the early

1990s, large food retailers such as Sainsbury (approximately 18 per cent of market share),

Tesco (15 per cent), Gateway (13 per cent), the Co-op (12 per cent) and ASDA (8 per cent),

dominated food sales to consumers, becoming the price setters for the products of the food

processing sector. Those prices then influenced price levels in contracts offered to farmers

by individual food processors. In addition, large multiple retailers are able to offer contracts

directly to those larger farm businesses and farmer co-operatives which can meet exacting

standards of volume, quality, timeliness, price and packaging for certain products—for

instance potatoes and eggs. By the mid-1990s, the top six retailers controlled 86 per cent of

the grocery market in the UK, leading to the further demise of the small grocer and

greengrocer in urban and rural areas alike.

So as to obtain a degree of ‘countervailing power’, farmers with larger businesses

continue to group together to develop marketing co-operatives for their contract negotiations

with food processors and retailers. By offering a product of the necessary assured quantity

and quality, farmer co-operatives attempt to negotiate more favourable contract prices,

although with variable results. Probably of greater importance for the economics of individual

farm businesses is the passing of responsibility for marketing from the individual farmer to

the specialised staff of the co-operative. Potatoes, vegetables, pigmeat, fruit and poultrymeat

are the products most associated with the development of co-operative marketing in the

1990s (Table 5.13). The distribution of farmer co-operatives around the UK reflects the

prior regional location of these different products (Bowler 1982:96).

Many smaller farmers, however, are seeking other ways of by-passing the marketing

chain and gaining direct access to consumers, thereby achieving a higher price for their

products. For example, experience in the 1980s with the development of pick-your-own

and farm shops (Bowler 1982:96) is being extended to the development of farmers’ markets,

as found already in North America. In the organic farming sector, smaller producers are

selling their fruit, vegetable and livestock products locally through retail outlets or

increasingly popular ‘vegebox’ schemes. Under this latter system a network of local

AGRICULTURE

105

customers pay a fixed amount to an organic producer to receive a weekly box of seasonal

fruit and vegetables. Other smaller producers are addressing a further aspect of ‘green’

consumerism, namely the increasing niche market for speciality or ‘quality’ foods, such as

farm cheeses, yoghurts and meat products. These markets tend to be local in extent and

supplied mainly through retailers. Producers are having to group together to be able to

advertise and supply larger regional and national markets.

Multiple retailers have responded to the commercial potential of ‘green’ consumerism

by introducing organic and ‘conservation grade’ foods into their stores and developing

networks of farmers who are able to comply with their own schemes of assurance as regards

food safety, including the traceability of food products. Competition under the third food

regime between farmers and food retailers for the growing number of ‘green’ consumers is

underway.

Conclusion

Two concluding observations can be made as regards the likely condition of UK

agriculture in the early decades of the next millennium. First, just as a spatially

differentiated agriculture developed under the productionist imperatives of the second

food regime, so varying regional combinations of productionist and post-productionist

agricultural trends will continue to evolve within the UK. How far and how fast such

trends as the increased extensification, diversification and ‘greening’ of farming practices

and structures take place will be conditioned in large part by the next round of reforms

to the CAP (‘Agenda 2000’), the further enlargement of the EU, and the WTO

negotiations of 2002/3. The promised deepening and extension of the 1992 reforms,

especially the further scaling down and decoupling of financial support from production,

seem likely to strengthen the development of post-productionist over productionist

developments in agriculture.

Second, just as agriculture is subject to its own ‘internal’ restructuring, so the sector is

coming under increasing ‘external’ pressures from other users of rural land, including urban,

recreation, tourism and conservation interests. A number of different regional contexts have

been identified in this restructuring of rural space (Marsden 1997), including ‘preserved’,

‘contested’, ‘paternalistic’ and ‘clientelist’ countrysides. The economic and social roles of

agriculture will vary within and between such new rural spaces: in particular farm production

could become increasingly concentrated within the UK in the most productive areas as

regards climate, soil and large-farm structure, with farming in the remaining ‘marginalised’

areas oriented more towards housing, recreation, tourism and conservation functions. In

these circumstances, agriculture’s place in the economy and society will be interpreted

increasingly within the wider processes of rural development and in regional (i.e. endogenous)

rather than national and international (i.e. exogenous) contexts.

References

Battershill, M. and Gilg, A. (1996) ‘Environmentally friendly farming in south west England’, in N.

Curry and S.Owen (eds) Changing Rural Policy in Britain, 200–24, Cheltenham: Countryside &

Community Press.

Bowler, I.R. (1979) Government and Agriculture: a Spatial Perspective, Harlow: Longman.