Gardiner V., Matthews H. The changing geography of the United Kingdom

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

CHARLES PATTIE

316

separate Scottish, Welsh and Northern Irish parliaments was passed in 1997 and 1998 (in

Northern Ireland alone, this meant the reintroduction of a form of ‘home rule’). At the same

time, moves towards the ever-greater integration of the European Union led to greater ‘pooled’

sovereignty between the United Kingdom and other EU countries. For some commentators,

at least, the country at the end of the century seemed a disunited kingdom.

From consensus politics…to a new consensus?

British politics has moved since 1945, from cross-party consensus, through a period in

which consensus disappeared, to a new consensus (Taylor 1991). The post-1945 consensus

was built on a cradle to grave welfare state, and on Keynesian policies for economic growth

and full employment. The new policies, largely agreed by the wartime coalition, were enacted

by the 1945 Labour government. But the Conservative Party too had to adapt to the new

circumstances to be re-elected. While inter-party differences remained, the post-war years

were marked by broad policy consensus between the major parties (Kavanagh and Morris

1989). Under the conditions of the long post-war economic boom, the consensus seemed to

have ‘solved’ Britain’s economic and social problems.

But the onset of recession in the early 1970s brought the consensus to an end. Keynesian

policies no longer seemed to allow governments to control the economy effectively.

Unemployment and inflation both grew rapidly. By the end of the decade, monetarism was

emerging as the new ‘accepted wisdom’, at least on the right of the political spectrum.

Policy was geared to keeping inflation down, and to reducing state ‘interference’ in the

running of market economies (Johnston 1993). The price was the abandonment of full

employment as a policy goal: unemployment grew to levels unprecedented in the post-war

period.

Labour in government in the 1970s had been reluctant converts to monetarism. But

the Conservatives in opposition adopted it enthusiastically. Their programme (which some

termed Thatcherism, after Margaret Thatcher) broke with the post-war settlement.

Thatcherism contained two strands: ‘the free economy and the strong state’ (Gamble 1988).

The ‘free economy’ reflected a belief in the greater efficiency and desirability of markets

than of government intervention in the economy. Over the next eighteen years Conservative

governments tried to cut state expenditure (not always successfully), and privatised state-

owned industries. The ‘strong state’ referred to the maintenance of law and order, and to

increasing political centralisation in Whitehall during the 1980s. Thatcherism transformed

Britain irrevocably. Nor were the changes restricted to the balance between state and private

sector. By the late 1990s, a new political consensus was emerging.

In the early 1980s, however, a new consensus seemed remote. The Conservatives in

government moved right and Labour in opposition moved left (Seyd 1987). A group of

prominent Labour right-wingers left the party in 1981 to form the Social Democratic

Party (Crewe and King 1995). With the Liberals, as the Alliance, for a brief period in

1982 they seemed set to eclipse both Labour and Conservatives. By the 1983 election,

support for the Conservatives had recovered. But Labour only just saw off the Alliance

challenge.

The 1983 election result was Labour’s worst performance in terms of vote share

since 1918. A radical rethink was required. The party moved to the right (Shaw 1994). In

part, Labour’s policy review was a recognition that voters saw the party as dangerously

A DIS (UNITED) KINGDOM

317

extreme in 1983: by moderating its position, the party hoped to move closer to the ‘centre

ground’, winning votes along the way. In part, too, however (and especially after 1987),

the policy review was a recognition that the changes wrought by the Conservatives were

in many cases irreversible. Rather like the Conservatives after 1945, Labour had to adapt

to the new circumstances in order to stand a realistic chance of governing again. But it

was not until the 1992–7 parliament that the party was perceived to have changed

sufficiently for it to win an election: under its new leader, Tony Blair, the party abandoned

Clause 4 of its 1918 constitution and made clear it was no longer a ‘tax and spend’ party.

Helped by Conservative disarray over the economy and Europe, Labour won a landslide

victory in 1997 (Pattie et al. 1997).

By the 1997 election, there was little to choose between the major parties in terms of

most major policies: both were committed to free markets, to relatively limited state

involvement, to low taxation, and so on. A new political consensus had emerged. They

diverged primarily on constitutional matters: Labour was committed to devolution for

Scotland and Wales (as were the Liberal Democrats), while the Conservatives were strongly

opposed.

The movement of Britain’s political elite from old (social democratic) to new (post-

Thatcherite) consensus is clear. But public support for the post-war consensus remained

strong (Crewe 1988; Pattie and Johnston 1996). In 1997, 92 per cent of the population felt

that government should spend more to eradicate poverty, and 61 per cent felt that income

and wealth should be redistributed (British Election Study 1997). Support for welfare state

institutions such as the National Health Service (NHS) remained almost universal.

But support for the welfare state was mediated by private concerns over prosperity

(Sanders 1996). Many vote in line with their views on the state of the economy, and of their

own personal financial situation: if they feel prosperous, they are more likely to support the

government, even if that means supporting a party whose policies on the welfare state they

feel uneasy about. But the corollary also holds that if they feel the economy is doing badly,

they will hold the government responsible and vote against it. This creates electoral pressures

which make it difficult to reverse social inequalities, and which may, in fact, exacerbate

them (Galbraith 1992).

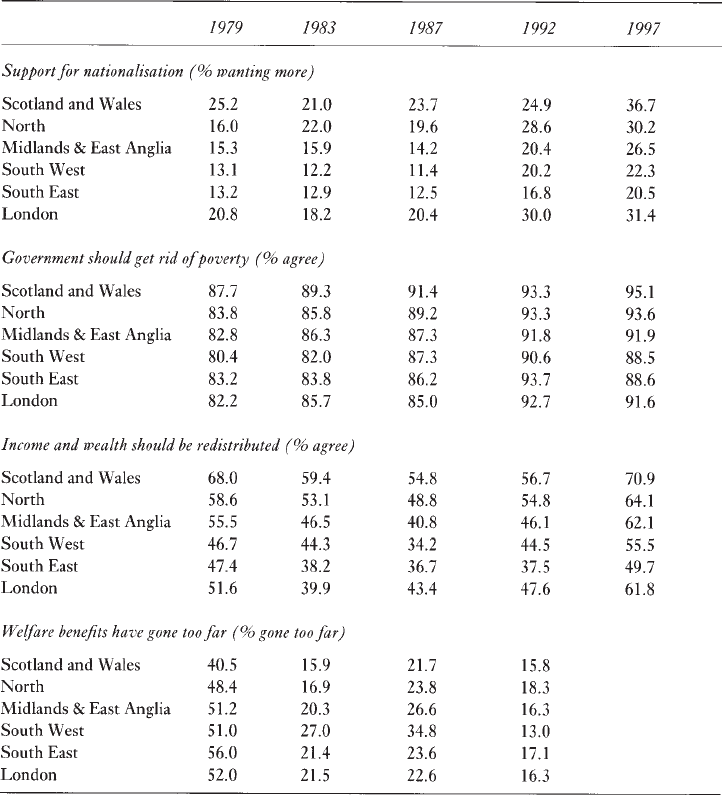

The analysis of public opinion also reveals a (dis)united political geography. Focusing

on the crucial years between 1979 and 1997, support for some aspects of the welfare state

was widespread (Table 16.1). Large majorities in all regions thought that government should

spend money to alleviate poverty. Although there were some differences across regions

(with people living in the South outside London being slightly less convinced than people

living in London and the North), these were not large, and there is clear evidence in all

regions of growing public support for government action between the 1980s and 1990s.

But there were substantial cross-regional and cross-temporal variations in public

support for some other aspects of the post-war settlement. Unsurprisingly in a climate of

privatisation, support for the reverse process, nationalisation, was very low in all areas. But

it grew in all regions after 1987 (in part a response to growing public disquiet over some of

the privatised utilities). Furthermore, it was consistently higher in the North than in the

South (excluding London). Similarly, support for the redistribution of income from rich to

poor was backed by a majority in the North, while in the South it was supported by a

minority (and a declining one between 1979 and 1992). Finally, despite government rhetoric

focusing on ‘scroungers’ living off welfare benefits, there is little evidence that voters felt

CHARLES PATTIE

318

provision of benefits had ‘gone too far’ after 1979. In part, this reflects persistently high

levels of unemployment in the 1980s especially. But even here, there is some evidence of a

(narrow) North-South divide in attitudes during the 1980s, which closed somewhat in the

1990s (unfortunately, the question was not repeated in 1997).

This suggests that the new elite political consensus has only shallow roots in the

population, and that support for it has been higher in the South than in the North. The

ideological divides of the period of ‘high Thatcherism’ (1979–87) were reflected in regional

divides in public opinion (see also Pattie and Johnston 1990). During this period, Britain

became more ‘disunited’. But since 1987, the North-South divide in political attitudes has

TABLE 16.1 Support for the post-war consensus, by region, 1979–97

Source: British Election Studies, 1979–97.

A DIS (UNITED) KINGDOM

319

narrowed (Curtice 1996). National disunity has decreased, at least as far as public opinion

is concerned.

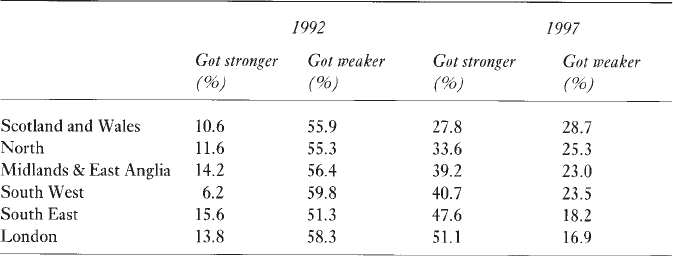

During the 1980s and 1990s there were also regional divides in how people evaluated

the state of the economy, and these divides reflected real differences (Table 16.2; Hudson

and Williams 1995). Reflecting the recession conditions of the 1992 election, a majority of

voters then thought the national economy had got worse. But people in the South East

(outside London) were still slightly more likely to feel things had got better over the preceding

year than were voters living in the North, despite the region’s economic downturn. By

1997, with the economy in recovery, especially in the South, the regional differential in

perceptions of economic performance had widened again to produce a pronounced North-

South split: only 28 per cent of Scottish and Welsh voters thought the economy was stronger

than in the previous year (though this was in itself an improvement on the situation five

years earlier), compared to 48 per cent of voters in the South East. Compared to 1992, the

1997 figures represent a return to the status quo of the 1980s: residents in the South East are

optimistic about the state of the economy relative to residents further north.

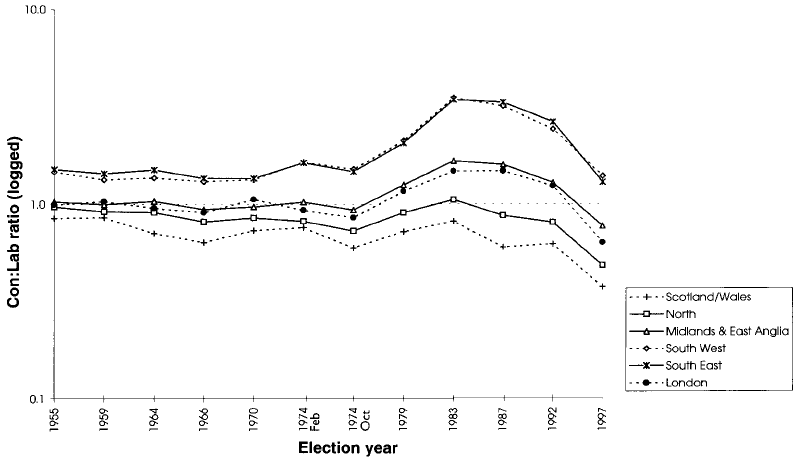

The geographies of public opinion and of public perceptions of economic well-being

combined to influence the geography of the vote. Once again, the country became more

disunited during the 1980s, and then more united again in the 1990s. One way of showing

this is to compare the ratio of Conservative to Labour votes in the regions across a series of

elections. Where more people support the Conservatives than Labour, the ratio is greater

than 1; where more support Labour than Conservative, it is less than 1 (Figure 16.1). A

North-South divide in voting patterns is a long-established feature of British elections,

reflecting the underlying geography of social class. But in the 1980s that divide grew very

rapidly. Labour’s vote fell throughout the South, while the Conservatives did relatively

poorly in the North (and Labour held on there). By 1987, it seemed that Britain was ‘a

nation dividing’ along grounds of political allegiance (Johnston et al. 1988). Recession-hit

northern voters rejected the Conservatives while affluent southern voters rewarded it. But

the process was not ineluc table. As Labour moved back into the centre ground in the 1990s

and as renewed recession hit the previously affluent voters of the South, so the electoral

divide narrowed again at both the 1992 and 1997 elections. However, it is worth noting that

the regional electoral divide in 1997, while not as wide as in 1987, was still wider than it

TABLE 16.2 Perceptions of prosperity by region, 1992–7

Source: British Election Studies.

CHARLES PATTIE

320

had been in the 1950s and 1960s, the years of the post-war consensus. Britain remains

divided electorally, although the trends are towards unity rather than disunity.

Nationalist challenges

Ironically, while the 1992 and 1997 elections reveal a closing of the political divide between

the regions, and the major parties share more common ground than at any time since the

late 1960s, other forces are at work which may weaken the bonds between different parts of

the United Kingdom. Crucially, these forces operate in the main remaining area of substantial

difference between the major parties, the constitution, and in particular, devolution of power

to the regions. But renegotiating the relationship between Westminster and the regions means

walking a fine line on issues of national sovereignty.

Northern Ireland

Ireland was the exception in the development of a British sense of national identity. Under

British rule it was in some ways more a colony than part of an economically advanced

nation-state. When a sense of Britishness was being forged in the eighteenth century, the

Catholicism of much of the Irish population was at odds with British Protestantism. A history

of repression and neglect fostered a series of nationalist risings, and, in the latter half of the

nineteenth century, in political movements for greater Irish autonomy (Foster 1988). The

‘Irish question’ was an important factor in the politics of the late nineteenth and early twentieth

centuries. In arguments which were echoed almost a century later in discussions over Scottish

FIGURE 16.1 The changing regional geography of the vote, 1955–97, Conservative/Labour

vote ratios

A DIS (UNITED) KINGDOM

321

and Welsh devolution, some claimed home rule would fatally weaken the Union, and others

that it would save it. By 1914, it seemed the Liberal government was finally about to legislate

for home rule, but the outbreak of the First World War put an end to the plan. Some Irish

nationalists resorted to more militant, military, measures. Britain was forced to concede

Irish independence.

The home rule debate was complicated, however, by divisions within Ireland itself. A

substantial Protestant minority, especially in the north-east around Belfast, was strongly

opposed to home rule, fearing it would be the first step to outright independence. To

accommodate this minority, Ireland was partitioned, and the six counties of the north-east,

where it was in a majority, remained in the UK. Ironically, given Unionist opposition to

home rule for the whole island, Northern Ireland was given its own parliament, Stormont,

and substantial devolution of power within the UK. Stormont was dominated by Unionist

politicians. The Catholic minority in the north was discriminated against in employment, in

political representation, and in access to social goods, especially housing (O’Leary and

McGarry 1996). The 1922 settlement contained the seeds of future conflict.

Stormont’s violent handling of the Catholic civil rights movement in the late 1960s

brought renewed civil disorder. In response to a rising tide of inter-communal violence

(mostly directed against Catholics, and sometimes involving the Northern Irish police), the

British army was deployed on the streets of Northern Ireland in 1969. In 1972, Stormont

was suspended and direct rule from Westminster was instituted. With one abortive exception,

the 1973 Sunningdale Agreement (O’Leary and McGarry 1996:198ff.), no serious attempt

was made to devolve power back to the province for a quarter of a century.

Politics in Northern Ireland has been polarised to a greater degree than in any other

part of the United Kingdom. In part, this was reflected in the climate of sectarian violence,

with paramilitary organisations responsible for terrorist acts both in the province and

beyond. But it also found a reflection in party politics. Whereas elsewhere in the UK the

major parties developed along class lines, in Northern Ireland they reflected communal

ties. Unionist parties draw their support almost exclusively from the Protestant community,

while nationalist parties draw support from Catholics. There is little or no cross-communal

party support.

But divisions exist within as well as between the two main camps (Evans and Duffy

1997; Graham 1998). The once solid bloc of Unionism fractured in the late 1960s and early

1970s over the extent to which nationalist demands should be accommodated. The Official

Unionist Party represents the old, traditional unionism, while Ian Paisley’s Democratic

Unionist Party (DUP) draws support from a more hard-line, working-class constituency.

The Social Democratic Labour Party (SDLP), which emerged as the major voice of

nationalism in the 1970s, has faced growing competition for Catholic votes from Sinn Fein

(often seen as the political wing of the IRA) since the latter party decided to abandon its

opposition to participation in elections in the 1980s. One consequence has been to make

compromise difficult, as more moderate politicians have had to take account of the likely

impact on their support of concessions. Equally striking has been the almost total absence

of the ‘mainland’ parties from the province’s politics. At the 1992 and 1997 elections, some

Conservative candidates stood for Ulster seats, but they did so without the full backing of

their party.

Nor has there been consensus over desired constitutional arrangements (McGarry

and O’Leary 1995). In the nationalist camp, the SDLP advocates a parliamentary road to

CHARLES PATTIE

322

Irish reunification. While campaigning on behalf of the nationalist community in

Westminster, and advocating an increased ‘Irish dimension’ to politics in the province,

the SDLP has seen unification as a long-term goal. By contrast, Sinn Fein (SF) advocated

until recently a dual strategy of military and electoral struggle—the armalite and the

ballot box. SF MPs, when elected, have refused to take up their seats (though the party

has played a more active role in local politics). Unionists too have been divided (Graham

1998). One model has been to win the re-establishment of a Stormont parliament—in

other words, devolution within the UK, with no (or limited) concessions to nationalists.

Another—minority—view has been that Northern Ireland should become independent of

both the UK and Ireland. Yet others have advocated ‘normalising’ relationships with

Britain. Under this model, Northern Ireland would be no different to the other UK regions,

the major UK parties would compete there, and (as a side-effect) the threat of Irish

unification would be removed at a stroke.

But Northern Ireland’s problems are not due simply to internal factors: the British

and Irish government are also implicated. Solutions are elusive, but most recent attempts

have involved both governments. Beginning with the 1985 Anglo-Irish agreement, the

Irish and British governments have increasingly co-operated with each other. A growing

recognition in the 1990s that neither the British army nor the paramilitaries—both

republican and unionist—could achieve an outright military victory also helped foster a

climate within which dialogue could take place. From small beginnings in 1991, talks

began between the various parties involved in Northern Ireland. Despite sometimes severe

setbacks, all parties —including those linked to paramilitaries, once ceasefires had been

announced—became involved. While not accepted by all parties to the negotiations (the

DUP and some Official Unionists remained opposed), an agreement was reached on Good

Friday 1997.

All sides made concessions. An elected Northern Ireland assembly was to be

established, with a power-sharing executive of twelve ministers, guaranteeing both

communities a say in the government of the province. The Irish government agreed to hold

a referendum on changing clauses 2 and 3 of the Irish constitution, which laid claim to

Northern Ireland and have proved a significant sticking point for unionists. At the same

time, in a concession to nationalists, a Ministerial Council would be established, consisting

of ministers in both the Belfast and Dublin governments, to foster joint policy-making on

areas of common interest, as would a British/Irish council, involving politicians from all the

parliaments in the islands—Dublin, London, Belfast, Edinburgh and Cardiff. Finally, the

Good Friday Agreement was to be put to referendum in both parts of Ireland. The vote,

when it came, was overwhelming: on a huge 81 per cent turnout, 71 per cent of voters in

Northern Ireland agreed to the terms of the deal (on a lower, 56 per cent turnout, it was also

endorsed by 94 per cent of voters in Ireland).

The success of the Agreement is not guaranteed. Elections for the new Northern

Ireland Assembly, conducted in June 1998, revealed large splits within the unionist camp,

for instance. But the arrangements for power-sharing and for the involvement of both

British and Irish governments represent a considerable constitutional shake up, with

concessions for both sides. Furthermore, although disputes remain over the

decommissioning of weapons, the main paramilitary groups seem set on maintaining

their ceasefires. The Good Friday Agreement provides one of the best prospects for peace

in a generation.

A DIS (UNITED) KINGDOM

323

Scotland

Unlike the other countries of the United Kingdom outside England, Scotland had a long

history as an independent and consolidated state, from the thirteenth- and fourteenth-century

wars of independence to the 1707 Act of Union. Even after Union, many of the institutions

of an independent Scottish state remained: Scottish law differs from English law; the

Presbyterian Church of Scotland is the ‘state church’, not the Episcopalian Church of

England; the education system, from school to university, is different; there is a distinctive

and flourishing national press, and so on. And since 1885, Scottish affairs have been

represented in government by a separate, powerful department of state, the Scottish Office

(Mitchell 1996).

A shared sense of Scottish nationhood has never been far below the surface of Scottish

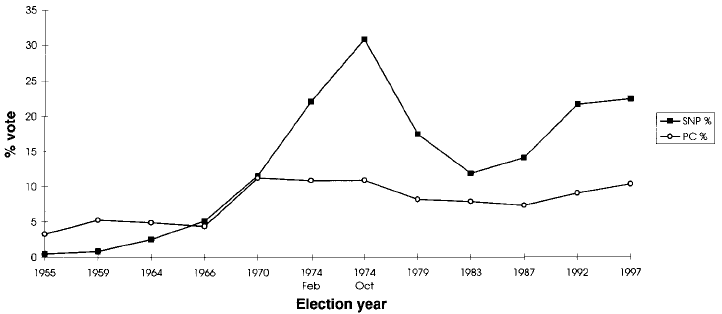

politics. The 1970s saw the start of the most recent upsurge in demands for Scottish home

rule, with the election of Scottish Nationalist Party MPs. While the SNP never achieved

majority support (even at its October 1974 peak, it won only 30 per cent of the Scottish

vote, and took eleven out of seventy-one seats: Figure 16.2), it did play a considerable part

in putting the issue of Scottish self-government back onto the political agenda, forcing the

minority 1974 Labour government to introduce legislation for Scottish and Welsh elected

assemblies. A referendum was held on the issue in 1979. Although a small majority of those

voting favoured devolution, the margin fell below a threshold of 40 per cent of the electorate

stipulated in legislation. The devolution proposals fell.

The incoming Conservative government opposed devolution. If anything, it further

centralised power. During the following eighteen years, Scottish self-government was off

the national (UK) political agenda. But the issue did not go away.

Ironically, it was the very electoral success of the Conservatives throughout the 1980s

and early 1990s which helped rekindle demand for a Scottish parliament. The beliefs and

policies espoused by the Conservatives under Mrs Thatcher were particularly unpopular in

Scotland (see Pattie and Johnston 1990; Bennie et al. 1997), and the Scottish economy did

not perform well enough, relative to the South of England, to compensate. Furthermore, the

FIGURE 16.2 Vote share for Scottish and Welsh nationalists, 1955–97

SNP=Scottish Nationalist Party; PC=Plaid Cymru

CHARLES PATTIE

324

Conservatives gained a reputation in Scotland (how deserved is open to debate) as being at

best uninterested in, and at worst actively antagonistic to, Scottish interests.

The net effect was to increase Scottish resentment of the Conservative government

and to foster demands for a separate Scottish parliament. Prime Minister John Major

believed that his anti-devolution appeal for the preservation of the Union, during the

1992 General Election campaign, was instrumental both in snatching an overall victory

for the Conservatives and in effecting a slight improvement in the party’s fortunes in

Scotland. This led him to repeat his warnings about the possible break-up of the UK

during the 1997 election campaign. In fact there is little evidence that Major’s appeals for

the preservation of the constitutional status quo made much impact on the Scottish

electorate. The much-vaunted recovery of the Conservatives’ Scottish vote in 1992 was

in fact very slight.

None the less, successive Conservative Secretaries of State for Scotland made much

of their ability to win concessions from government. Nor were they averse to playing the

‘tartan card’. For instance, Michael Forsyth, the incumbent Secretary of State before the

1997 election, wore a kilt at the premier of the film Braveheart (which romanticised the

exploits of William Wallace, a hero of Scotland’s wars of independence in the late thirteen

century and the early fourteenth; Braveheart was also used as a rallying device by the SNP),

and was responsible for the well-publicised and highly symbolic return of the Stone of

Destiny to Scotland.

A renewed commitment to devolution from both Labour and the Liberal Democrats

was one manifestation of a revived home rule campaign in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

The Scottish Constitutional Convention was another. Launched in 1989, the Convention

involved most of the groups campaigning for a Scottish parliament, including the Labour

and Liberal Democrat parties in Scotland, the Scottish TUC, and the Scottish churches

(although the SNP, worried about its pro-independence principles being diluted, declined to

participate). It provided a cross-party forum within which proponents of a parliament could

meet, agree common goals, and conduct common campaigns.

Labour’s 1997 landslide election victory put the issue back at the forefront of the

Westminster agenda. Subject to ratification in the referendum, Scotland was to be offered a

relatively strong parliament, with powers over many aspects of daily life. Furthermore,

proposals were laid to give the parliament highly symbolic (if in practice rather limited)

powers to raise some of its own tax revenue. As a consequence, the Scottish referendum

asked two questions, therefore: whether voters supported the idea of a Scottish parliament;

and whether the parliament should be given tax-varying powers. Attempts by the SNP to

draft a question giving voters three options—the status quo, a Scottish parliament within

the UK, and outright independence—came to nothing, however. The future of the Union

was not in question in the referendum.

Pro- and anti-devolution campaign groups were formed (see Mitchell et al. 1998).

Formally, these were non-partisan organisations drawing together supporters and opponents

of home rule from across the political spectrum, but in fact the composition of the groups

largely reflected the previous positions of the main parties on the issue. Labour, the Liberal

Democrats and the SNP came together under the aegis of Scotland Forward to campaign for

a ‘Yes’ vote on both referendum questions. In itself, this was a remarkable achievement.

Not only had the SNP refused to join the Constitutional Convention, but relations between

Labour and the SNP are poor, as the latter vies to replace the former as Scotland’s ‘majority’

A DIS (UNITED) KINGDOM

325

party. But the parties agreed to co-operate in the 1997 referendum campaign, avoiding

potentially damaging splits. The main ‘No’ campaign group, meanwhile, was Think Twice.

Although ‘No’ campaigners were anxious to dispel any notion that they were all

Conservatives and that Think Twice was merely a Conservative ‘front’ organisation, that, in

fact, is fairly close to the truth.

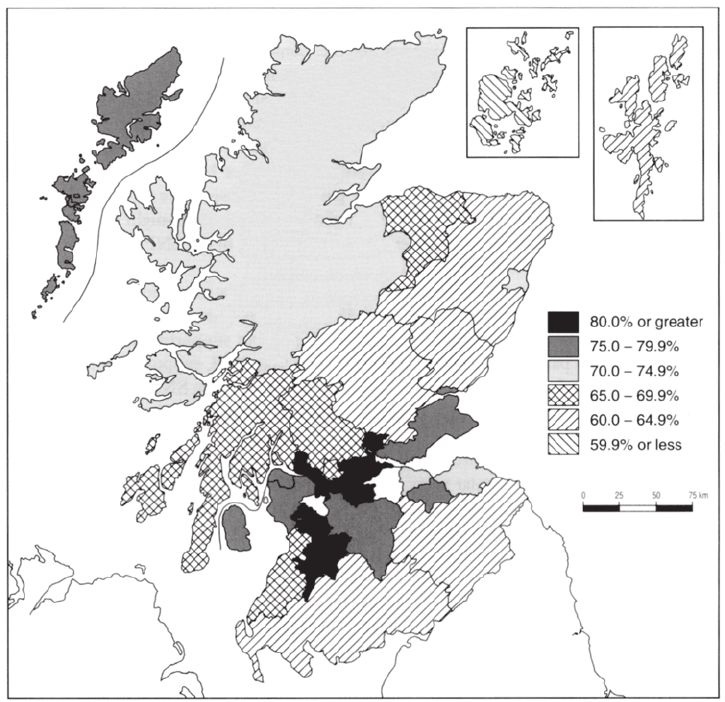

The referendum was held on 11 September 1997. The result on the first question was

never seriously in doubt. On a respectable 60 per cent turnout, a substantial majority (74 per

cent) of Scottish voters supported the establishment of the first separate Scottish parliament

since 1707, a much more substantial majority than that achieved in 1979. And whereas in

1979 majorities in some parts (notably the Borders and the Northern Isles) of Scotland had

actually opposed devolution, in 1997 majorities in favour were returned from all parts of

the country (Figure 16.3).

FIGURE 16.3 Percentage voting ‘Yes’ to a Scottish Parliament