Gardiner V., Matthews H. The changing geography of the United Kingdom

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

CHRIS PARK

456

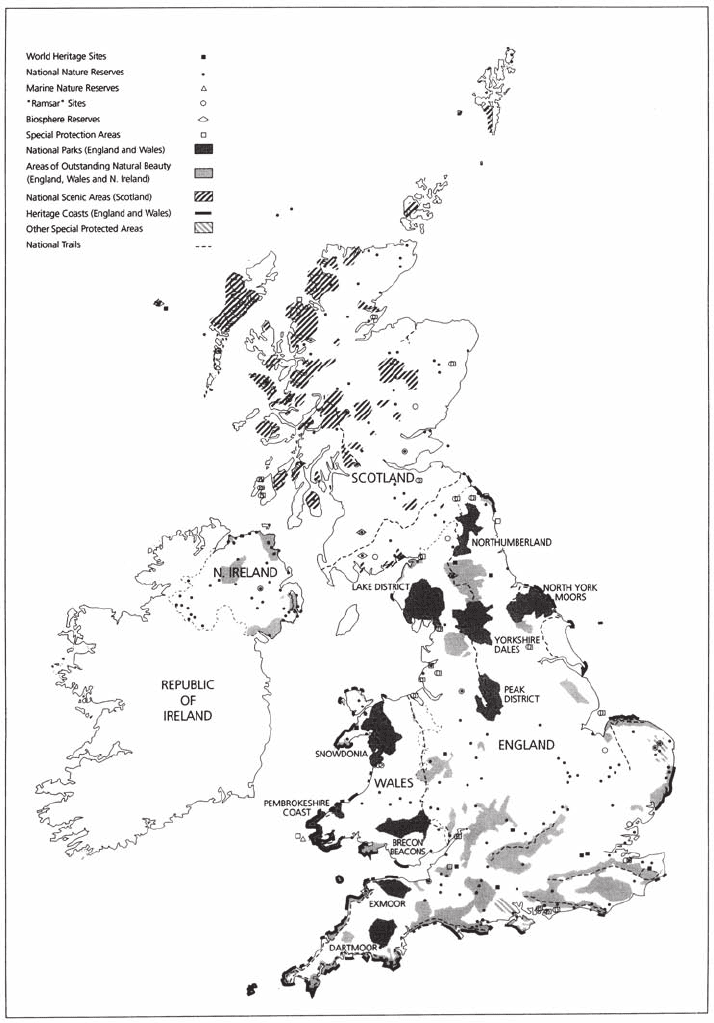

FIGURE 20.1 Protected areas in the United Kingdom as at 18 October 1993

Source: Countryside Commission.

CONSERVATION AND PRESERVATION

457

National Parks cover nearly 14,000 square kilometres, roughly 7 per cent of the land area

of England and 20 per cent of Wales.

Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty

Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty have also been designated under the 1949 legislation.

These are smaller than National Parks, still protected by tight planning controls, and closer

to the main centres of population and hence accessible to large numbers of visitors. The

total area of AONBs in England, Wales and Northern Ireland rose from just over 19,000

square kilometres in 1984 to 22,740 in 1990 and 24,000 in 1995. By late 1995 the forty-one

AONBs covered about 16 per cent of England, 20 per cent of Northern Ireland, and 4 per

cent of Wales (Table 20.8). National Scenic Areas in Scotland, which covered just over

10,000 square kilometres (13 per cent of the land area) in 1995, serve the same purpose as

the AONBs.

Heritage Coasts

In addition to the National Parks and AONBs there is a special landscape designation to

protect attractive or important stretches of coastline. Heritage Coasts are defined following

recommendations of English Nature or Welsh Nature, and they are managed by local

authorities via the planning system. By late 1995 some forty-four Heritage Coasts had been

defined, covering more than 1,500 kilometres (roughly a third) of the coastline of England

and Wales.

Wildlife designations

The two most important designations for conserving wildlife are National Nature Reserves

(NNR) and Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) in Great Britain, which are called

Areas of Special Scientific Interest (ASSI) in Northern Ireland. These national designations

form the basis for a network of nature conservation protection areas (Figure 20.1), which

also includes sites protected in order to meet international obligations, such as Special

Protection Areas for Birds (SPA) and Special Areas for Conservation (SAC) under the EC

Birds and Habitats Directives.

Some areas belong to more than one category of designation; for example, some

National Nature Reserves are also SSSIs, some SSSIs are also SPA sites, and many Ramsar

sites (see p. 460) are also designated as SPA sites.

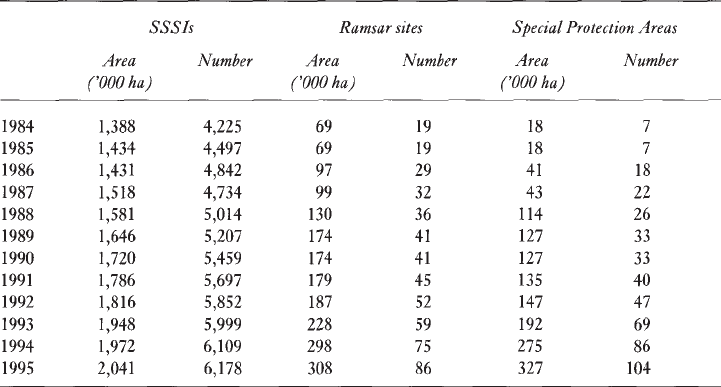

Sites of Special Scientific Interest

Sites of Special Scientific Interest are sites that contain important wildlife, geological or

physiographic features. They are notified by English Nature, although most are privately

owned or managed. About 40 per cent of the sites are owned or managed by public bodies

such as Forestry Enterprises, the Ministry of Defence and The Crown Estate, or by the

voluntary conservation movement. By mid-1995 there were more than 6,000 SSSIs covering

more than 20,000 square kilometres in England and Wales (Table 20.6), up from 4,225 sites

CHRIS PARK

458

covering nearly 14,000 square kilometres in 1984 (Table 20.9). Areas of Special Scientific

Interest (ASSIs) serve similar functions in Northern Ireland.

Special regulatory controls restrict the type and scale of development that can take

place on SSSIs, and they require specific consultation between site owners and English

Nature before approval is granted for developments that might alter the character and

ecological value of the site. English Nature liaises with about 23,000 owners and occupiers

of SSSI sites.

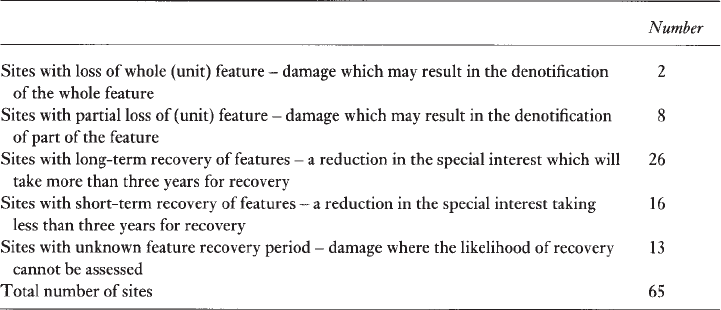

Despite the special protection offered to habitats and special features within

SSSIs damage can and does occur from time to time. The countryside agencies—

English Nature, Scottish Natural Heritage and the Countryside Council for Wales—

regularly collect information on damage to sites such as SSSIs. Environmental

indicator s3 (Table 20.3) summarises the extent of damage to designated and

protected areas.

The records suggest that damage occurs on only a small proportion of the total

number, and the extent of damage has decreased since the late 1980s (UK Government

1995). Most reported damage is short term, from which sites recover usually within three

years given appropriate management. The most common cause of short-term damage is

agricultural activities, but it can also be caused by factors such as pollution, unauthorised

tipping and burning. In 1994–5 around 12.5 square kilometres—0.05 per cent of the total

SSSI area—was affected by long-term damage (which will take more than three years to

recover). A small amount of damage is so serious that all or part of the SSSI is lost and

gets denotified. Table 20.10 shows the breakdown of damage to SSSIs during 1996–7.

English Nature concluded in 1997 that two-thirds of all SSSIs can be described as

favourable or recovering, and a further quarter have stabilised from decline. The other 10

per cent were classed as unfavourable because of ongoing agricultural activities (such as

overgrazing by sheep on some upland grasslands), inadequate positive management

TABLE 20.9 SSSIs, Ramsar sites and Special Protection Areas in Great Britain, 1984–94

CONSERVATION AND PRESERVATION

459

(particularly on lowland heath, grasslands and wetlands), and individual damaging incidents

(such as unauthorised ploughing or deep drainage).

But the damage records only show particular events, such as field drainage or road

building. Evidence about progressive changes within SSSIs, such as those associated with

long-term air pollution or unsuitable land management (e.g. overgrazing in the uplands) is

much less readily available.

National Nature Reserves

National Nature Reserves (NNRs) are sites that have been designated for special protection

because of their national importance as wildlife habitats. They are either owned or

controlled by English Nature or held by approved bodies such as the Wildlife Trusts

(Barkham 1994), and are carefully managed to conserve habitats and species. NNRs are

declared by English Nature or its predecessors under Section 19 of the National Parks

and Access to the Countryside Act 1949 or Section 35 of The Wildlife and Countryside

Act 1981.

Whilst nature conservation is the primary objective in NNRs, many of them are

managed to allow public access. Their wardens, conservation work and interpretative facilities

are funded by English Nature. There were a total of 333 NNRs in March 1995, covering an

area of nearly 2,000 square kilometres (Table 20.6). Most counties contain at least one

NNR, and the reserve network includes representatives of most types of vegetation within

the United Kingdom, including native woodlands, meadows, downlands, dunes and salt-

marshes. NNRs protect many of the country’s most scarce and threatened habitats, including

chalk downs, lowland heaths and bogs.

Despite their title, National Nature Reserves are not necessarily owned by the nation.

Neither are they necessarily permanent. Many NNRs survive by agreement between

landowners and English Nature, and if these agreements break down then NNR designation

and status can be removed. In a well-publicised case this is precisely what happened to

Braunton Burrows NNR in September 1996. Braunton Burrows in Devon, widely regarded

to be one of Britain’s finest National Nature Reserves, is one of the country’s three largest

TABLE 20.10 Damage to Sites of Special Scientific Interest, 1 April 1996 to 31 March 1997

CHRIS PARK

460

coastal sand dune systems and home to more than 440 plant species. It was listed as a

UNESCO Biosphere Reserve. But because of a disagreement with the owner of the site,

who refused to accept English Nature’s recommendation that the dune be grazed to

maintain the habitat, its status as a NNR was lost when English Nature was unable to

renew its lease. It remains as an SSSI, but—without the landowner’s agreement—grazing

could only be restored if the site were bought under a Compulsory Purchase Order.

Conservation groups, led by Friends of the Earth, called for a legal ‘duty of care’ for

landowners that would require them to manage sites in accordance with conservation

objectives.

Local Nature Reserves

Local Nature Reserves (LNRs) seek to conserve habitats and species that are important

locally and regionally within the United Kingdom. As such, they represent ‘First Division’

conservation sites compared with the ‘Premier League’ National Nature Reserves. Local

authorities, in consultation with English Nature, designate LNRs. All of the 487 LNRs,

covering a total of nearly 250 square kilometres in 1995, were owned or controlled by local

authorities. Some LNRs are also SSSIs.

Marine Nature Reserves

Marine Nature Reserve (MNR) designation is intended to offer particular protection to

coastal sites that contain nationally important habitats and species. Two such sites (Table

20.6) have been declared by the Secretary of State for the Environment—the island of

Lundy in the Bristol Channel, and the island of Skomer, off the south-west coast of

Wales.

Ramsar sites and Special Protection Areas

There are two special categories of designations that reflect the UK government’s

commitment to international conservation initiatives. In 1973 it signed the so-called Ramsar

Convention (more properly the Convention on Wetlands of International Importance), under

which it is committed to designate ‘Wetlands of International Importance’ (Ramsar sites)

and to manage the wetlands within its territory in sustainable ways. Between 1984 and

1995 the area covered by Ramsar sites increased from around 690 square kilometres to

more than 3,000 (Table 20.9), and in March 1995 there were eighty-six Ramsar sites scattered

throughout the United Kingdom.

The UK is also bound by the 1979 European Communities EC Directive on the

Conservation of Wild Birds (79/409/EEC). This requires the government to designate Special

Protection Areas (SPAs) to conserve the habitat of certain rare or vulnerable birds (listed

under the directive) and regularly occurring migratory birds. Designated sites have to be

protected from significant pollution, disturbance or deterioration. By March 1995 there

were 104 SPAs in the UK, covering a total area of 3,270 square kilometres (Table 20.6). The

previous ten years had seen continuous growth from seven sites covering 180 square

kilometres (Table 20.9).

CONSERVATION AND PRESERVATION

461

All sites listed as Ramsar sites and Special Protection Areas are also designated as

SSSIs, and some sites qualify as both Ramsar and SPA sites. As with all SSSIs, English

Nature has responsibility for identifying and designating these sites, and for consulting

with owners, occupiers, local authorities and other interested parties.

Biodiversity

One of the buzzwords of nature conservation during the 1990s has been ‘biodiversity’,

short for ‘biological diversity’. It refers to the number and variety of different habitats and

species of wildlife living within an area, and is a useful measure of quality of environment

as well as ecological health. The UK government eagerly adopted both the rhetoric and

reasoning of biodiversity, gave it a high profile in its sustainable development strategy, and

is committed to successful implementation of the Rio Convention on Biodiversity (Raustiala

and Victor 1996).

Natural capital

A key objective in the government’s sustainable development strategy is to conserve, as far

as possible, the biodiversity of the country’s wildlife and habitats (Whitby and Adger 1996).

This natural capital amounts to more than 30,000 native species of animals (excluding

marine, microscopic and lesser known groups—such as mites and roundworms—of which

there are many thousands), about 2,300 species of higher plants, about 1,000 species of

liverworts and mosses, about 1,700 species of lichens, about 20,000 species of fungi, and

about 15,000 species of algae.

The emergence of new species and decline of existing ones is an inherent part of the

‘circle of life’ as species evolve, adapt and become extinct. Natural environmental change

promotes evolution and extinction, and the expansion and contraction of the range of

individual species. As a result, the country’s natural capital is never static. Climate change

is likely to make the UK warmer and wetter in the twenty-first century, which might

promote an increase in species diversity (Elmes and Free 1994). But since at least 1945

that capital stock has been depleted as many species and habitats have declined. Some

decline is perhaps inevitable given that some native species are at the geographical limits

of their natural range, or whilst the habitats that support some other species are small and

scattered.

Change and decline

Biodiversity in the United Kingdom has been adversely affected in recent decades both

directly and indirectly as a result of human activities—particularly urban expansion, transport

developments, the intensification of agricultural production, and the growth of plantation

forests. Many species of wildlife have become nationally extinct, or their populations have

declined so much that their survival is threatened. It is estimated that around 170 species of

plants and animals in the UK became extinct during the twentieth century, and that up to a

quarter of native species of fish, invertebrates, plants, and mosses are threatened or nationally

scarce.

CHRIS PARK

462

The evidence (UK Government 1995) suggests that while many native species are

still relatively common across the United Kingdom, between about 10 and 20 per cent of

native species are threatened. More than one-third of the 2,700 native species of mosses,

liverworts, and lichens are threatened or nationally scarce, as are about a quarter of the seed

plants, ferns, and related plants (about 2,300 species in total) and invertebrates (about 15,000

species).

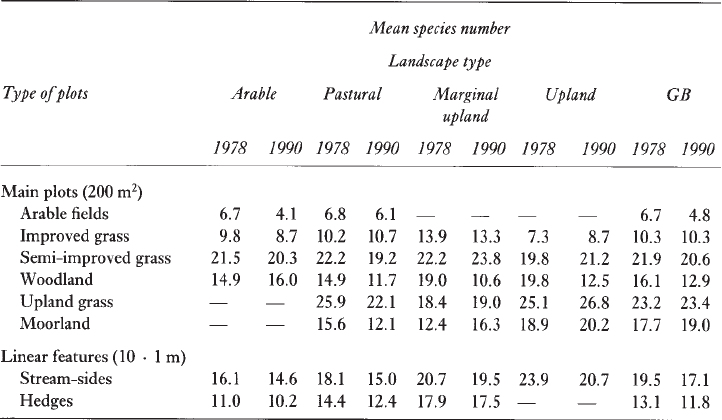

Many of these reductions in biodiversity are linked directly or indirectly with changes

in land cover, which inevitably reduces, damages or removes habitats. Comparison of results

from the 1978 and 1990 Countryside Surveys (Table 20.11) gives an indication of the scale

and pattern of change in plant species. For most landscape types there were fewer species

recorded in 1990 than in 1978, with declines often in the order of a quarter or more species.

High relative decreases were observed in arable fields, semi-improved grass pasture, upland

grass, moorland pasture. The number of species recorded in the sample plots of marginal

upland woodland fell by nearly a half between 1978 and 1990, and there was major decline

in upland woodland. It was not all bad news, however, because biodiversity in some habitat

types increased over that period. Relatively small increases were recorded in arable woodland,

semi-improved grass in marginal upland, upland grass, and moorland in marginal upland.

Most habitat types in the upland landscape type contained more plant species in 1990 than

in 1978. Plant species diversity in both stream-sides and hedgerows decreased, and decline

was recorded in every landscape type (Table 20.11).

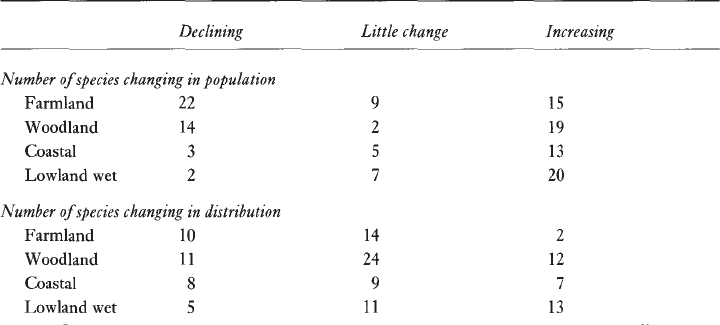

Other dimensions of biodiversity have also changed in the United Kingdom in recent

years, for much the same reasons as the changes in plant diversity. Records show that

the geographical distributions of just over a half of the species of dragonflies and

butterflies within Great Britain have reduced since the 1970s. Bird populations and

distributions (environmental indicator r2, Table 20.4) have also been affected by cover

TABLE 20.11 Changes in plant diversity within habitat types and linear features, Great Britain, 1978

and 1990

CONSERVATION AND PRESERVATION

463

change, habitat loss, pollution and natural factors (Andrews and Carter 1993). Population

size of twenty-two species of breeding birds in Britain fell between the 1970s and

1990s, and ten species experienced a decline in geographical distribution (UK

government 1996b). The fate of bird populations in woodland, coastal and wetland

habitats was more mixed, because more species increased in numbers than decreased

(Table 20.12). Almost a half (twenty-two species) of farmland species declined in

population size and around 40 per cent (ten species) decreased in their geographical

extent. Species reductions were relatively much higher on cultivated land than on grazing

land, although populations of some farmland species (such as jackdaw and magpie)

more than doubled. All bird species naturally occurring in the wild are protected under

the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981.

Habitat change and loss have also affected mammal populations (environmental

indicator r9, Table 20.4). By the late 1990s there were sixty-one species of land-based

mammal breeding in Great Britain, comprising thirty-nine native species, twenty-one

introduced and feral species, and one migrant species (Nathusius’ pipistrelle bat). More

than a third of British species of mammals appear to have declined in population size between

the 1969s and the 1990s, mostly smaller mammals such as rodents and bats. About a quarter—

mainly larger mammals such as carnivores or deer, and a number of non-native species —

appear to have increased.

Solutions

There is abundant evidence, from the Countryside Surveys and other sources, that the natural

capital of the United Kingdom is declining and has been doing so throughout most of the

post-war period. The government faces many challenges in turning this situation around,

given its desire to manage the nation’s environmental estate sustainably and its commitment

to international initiatives designed to conserve nature (most particularly the Rio Biodiversity

Convention, but also European Union directives and aspirations). It is fighting on many

fronts at the same time to try to stem the decline in species diversity, minimise the loss of

species, and limit the loss and fragmentation of and damage to habitats, whilst at the same

TABLE 20.12 Changes in diversity of breeding birds in Great Britain between 1968–72 and 1988–91

CHRIS PARK

464

time optimising productive use of the countryside. Conserving the biodiversity of the United

Kingdom is an important part of government policy (Palmer 1996).

A key priority is to conserve the habitats of species most under threat. In January

1994 the government published Biodiversity: the UK Action Plan in response to Article

6 of the Rio Convention on Biodiversity (UK government 1994b). Amongst other things,

the action plan established a Biodiversity Steering Group to formulate and oversee

national initiatives designed to conserve species and habitats. The Steering Group

recognise that the established network of designated areas—including SSSIs and schemes

such as the Environmentally Sensitive Areas—is a good foundation on which to build,

and which has already achieved some important successes in preserving the nation’s

ecological assets. But the existing network is too broad-brush to offer the sort of

protection that is essential for the survival of a number of particularly threatened species

and habitats.

In December 1995 the Biodiversity Steering Group published a set of proposed

specific, costed targets and action plans for 116 priority species and fourteen key habitats

of conservation importance (UK government 1996a). The habitat plans cover about 2

per cent of the land area of the United Kingdom. Between 1996 and 1999 the group

committed itself to preparing plans for an additional 286 priority species and twenty-

four key habitats. The targets and action plans, once agreed by government (UK

government 1996c), are intended to form the basis for conservation action in the UK

for the foreseeable future.

Set within this broader strategy aimed at conserving the nation’s biodiversity is a

number of more specific initiatives. One of the most prominent and most important of these

is the Species Recovery Programme mounted by English Nature. The programme is designed

to maintain or enhance populations of wildlife species that are in decline or threatened with

extinction, by directing action to halt or reverse the reduction in their range and number.

Recovery objectives are defined for specific species, and between 1991 and 1997 initial

recovery objectives were met for twenty-one of the species most at risk. By 1997 work was

being carried out on seventy-five species, most of them defined within the UK Biodiversity

Action Plan, through a series of partnership projects with a range of organisations and

individuals.

Partnership is central to both the spirit and purpose of the government’s approach to

nature conservation. Thus, for example, Species Action Plans for rare and threatened bird

species have been produced by the Joint Nature Conservation Committee, The Royal Society

for the Protection of Birds and The Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust (Williams et al. 1995).

English Nature is also keenly aware of the importance of empowering local groups to take

responsibility for their own environment (under Agenda 21), and the educational values of

partnership schemes in helping to change people’s behaviour and attitudes. English Nature

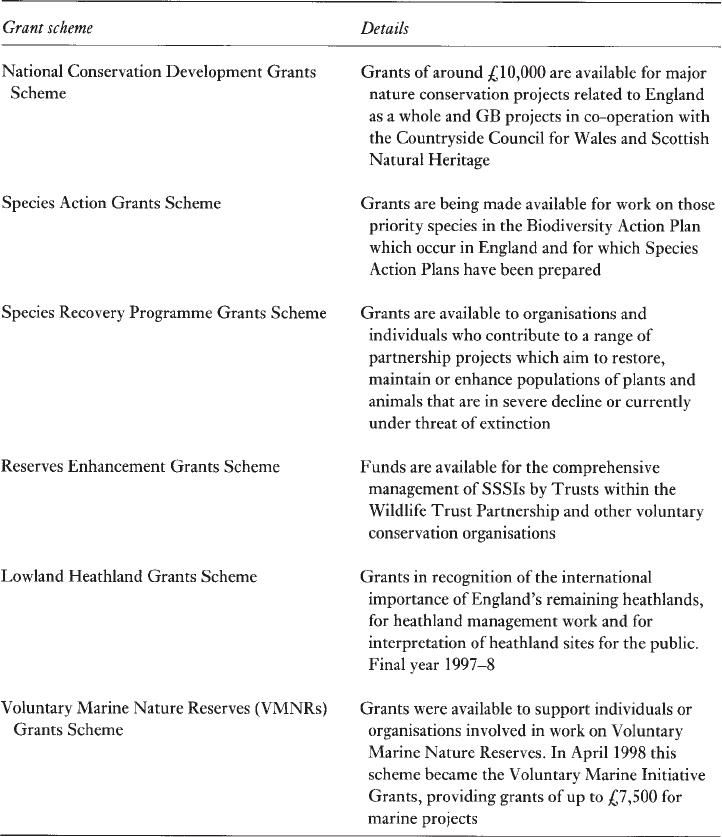

operate a variety of grant support schemes (Table 20.13) designed to engage the assistance

of other agencies, organisations and individuals in achieving the government’s nature

conservation objectives.

Some species of wildlife are already protected under national or international

legislation. There are strict controls, for example, on the possession, sale and display of

native wild birds, and those that are taken into captivity must be registered under the Wildlife

and Countryside Act 1981. Article 6 of EC Regulation 3626/82 also regulates the sale and

display to the public for commercial purposes of certain endangered birds. Most UK

CONSERVATION AND PRESERVATION

465

mammals are also protected under the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 and the EC Habitats

and Species Directive 1992. The UK government is also a signatory to CITES (the

‘Washington’ Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and

Flora), and takes seriously its responsibility to monitor and control trade in wildlife (such as

the trade in tiger and rhino products). The UK also ratified the ‘Bonn’ Convention on the

Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals. Through this it has signed the Agreement

on the Conservation of Bats in Europe which came into force in January 1994 and is designed

to encourage co-operation within Europe to conserve all its species of bats.

TABLE 20.13 National conservation grant schemes operated by English Nature, 1997