Gates Charles. Ancient Cities: The Archaeology of Urban Life in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece and Rome

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

332 ANCIENT ITALY AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE

gaining greater access to the ruling groups – a development that recalls the social and political

evolution of Archaic and Classical Athens.

In addition to the Senate, certain decisions were taken by various assemblies to which all citi-

zens, patricians and plebeians, were assigned either by birth or by level of wealth. The assemblies

were run by magistrates, generally aristocrats, of whom the consuls were the most important.

The magistrates controlled the proceedings, presenting their agenda of legislative proposals, but

the assembly voted the final decisions.

Serving as a method of organizing the Roman people, the assemblies (comitia in Latin) were

four in number. (1) The Curiate Assembly (Comitia curiata) was divided into thirty curiae, possibly

originating in kinship groups or regional families. Duties of this assembly included the confirm-

ing of appointments of magistrates and priests. (2) The Centuriate Assembly (Comitia centuriata)

was based on military organization, for its basic unit, the centuria, was, in the army, a group of

100 men, the smallest unit of a legion (one legion = sixty centuriae). However, by the fourth

century BC the direct link between the military and this assembly was lost; the centuria became

simply a voting unit. This assembly consisted of 193 centuriae, arranged in five ranks according to

property ownership. The greater one’s wealth, the greater one’s influence. Poorer men filled the

lower ranks; although far outnumbering the higher, their greater numbers gave them no advan-

tage in voting power. This assembly voted laws and declared war and peace. (3) In the Plebeian

Tribal Assembly (Comitia plebis tributa) and the related (4) People’s Tribal Assembly (Comitia populi

tributa), this last open to patricians as well as plebeians, the citizens were grouped according to

thirty-five tribes: four urban (the city of Rome) and thirty-one rural (in Italy). Election of certain

officials, enactment of certain laws, and the holding of minor trials constituted their role in gov-

ernment.

Conceived when the Roman Republic consisted of the city of Rome and, by the late third cen-

tury BC, the Italian peninsula, the system eventually broke down, overwhelmed by the expansion

throughout the Mediterranean that took place in the second century BC. The rapid inclusion of great

numbers of people, territory, and wealth disrupted the equilibrium of the social contract between

groups, leading to abuses and social unrest, and in the first century BC, dictatorship and civil war.

THE EXPANSION OF ROME

The dramatic expansion of Rome originated in the early fourth century BC with the conquest of

Veii, the Etruscan city closest to Rome. Then in 390 BC came a setback: raiding Gauls sacked

Rome. In response, the Romans built their first fortification wall, ca. 380 BC. Called the Servian

Wall after Servius Tullius, a sixth century BC king incorrectly believed to be its builder, this wall,

11km long, enclosed an area of 400ha on the east bank of the Tiber; included were the famous

seven hills. The city later developed well beyond the confines of this wall, although the area inside

continued to be defined as the city proper. A longer successor, enclosing a much larger area, the

Aurelian Wall, the second and final fortification of the ancient city, would come only much later,

in AD 271, its construction prompted by the unsettled conditions of the later empire.

In the Samnite Wars of the late fourth and early third centuries BC, the Romans confronted

and defeated their neighbors in central Italy, notably the Samnites, the Etruscans, and the Gauls.

Soon conflicts spread to the south, to a war with the Greek city of Tarentum (ending in 272

BC), and then to a dispute with Carthage for control of the island of Sicily (the First Punic War,

264–241 BC). By the later third century BC, Rome controlled all peninsular Italy, plus the islands

of Sicily, Corsica, and Sardinia. The absorption in particular of the Etruscan and Greek regions

ROME TO THE END OF THE REPUBLIC 333

with their rich cultural traditions had a tremendous impact on Roman society. Continuing con-

flict with Carthage (Second Punic War, 218–201 BC, and Third Punic War, 149–146 BC) led to a

decisive Roman victory and to Roman control over the west and central Mediterranean.

To celebrate these ongoing victories, the triumph became an institution: a parade in Rome,

paid by the victor from the spoils. From the early second century BC, these triumphs were com-

memorated by large free-standing arches (see the Arch of Titus and the Arch of Constantine, in

Chapters 23 and 25).

From ca. 200 BC, the Romans were increasingly drawn into the conflicts between Hellenistic

monarchs in the eastern Mediterranean, with territorial gains often the reward for their military

assistance. In 146 BC, Greece fell under de facto Roman control. Shortly thereafter, with the

Pergamene inheritance of 133 BC, the province of Asia was established in western Anatolia. The

Romans expanded westward, too. In 58–51 BC, Julius Caesar marched into north-west Europe,

conquering the area of modern France, Belgium, Germany west of the Rhine, and part of Swit-

zerland. Caesar was assassinated in 44 BC, a victim of the civil unrest that marked this turbulent

final century of the Roman Republic. Peace came only in 31 BC, when Caesar’s adopted son and

successor, Octavian, defeated his rival Mark Antony and the Egyptian queen Cleopatra VII at

the Battle of Actium off the north-west coast of Greece, thereby securing for Rome possession

of the entire eastern Mediterranean. In 27 BC Octavian adopted the title Augustus. The Republic

and the period of Roman expansion had come to an end; the Roman Empire had begun.

ROADS, CAMPS, AND COLONIES

The integration of these far-flung territories into the Roman state demanded an effective infra-

structure. Three key components of this infrastructure were roads, the establishment of army

camps, and the foundation of new towns, or colonies.

Roads

By the first century

AD, a vast network of roads would cover the empire. An early example was

the Via Appia, or the Appian Way, from Rome to Campania (the area around Naples), paved at

the beginning of the Samnite Wars in the late fourth century BC. Other famous roads included

the Via Flaminia, leading north from Rome to the Adriatic city of Ariminum (modern Rimini),

and the Via Egnatia, from Albania’s Adriatic coast to Thessalonica and Byzantium (later Con-

stantinople). Roman roads, at least the great intercity routes built by the state as opposed to local

or private sources, were remarkable in that they were not simply dirt tracks for wheeled vehicles,

but were stone-paved, suitable for all weather, and well-maintained. In addition, security was

constantly monitored. These qualities were deemed essential for facilitating rapid communica-

tions and deployment of troops across long distances.

Methods of construction varied. In the northeastern empire (Thrace, Asia Minor, and Syria),

the standard components of roads were three: (1) the edges were marked by large stones laid flat;

(2) a central line of smaller stones, set vertically on edge, divided the road into two; and (3) small

stones filled the two lanes. Elsewhere a trench might be dug, a foundation laid with edges curbed

to hold in the road and help drainage, and finally a surface added in a different material, such as

gravel or sand. Many roads would be suitable for both foot travelers and vehicles; others, in steep

areas, would have steps, and so use would be restricted to foot traffic.

334 ANCIENT ITALY AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE

Roads were marked at an interval of one Roman mile (=1.485km) by stone milestones of vary-

ing shapes and sizes, inscribed with distances and perhaps dates of construction or repair and the

names of the reigning emperor, local officials, and military units. For the traveler, road maps and

itineraries existed, although they were diagrams, not to scale, or lists of places on a single route,

with distances marked. The traveler could count on roadside establishments at periodic intervals

for room and board, mail service, stables and other transportation services.

Army camps

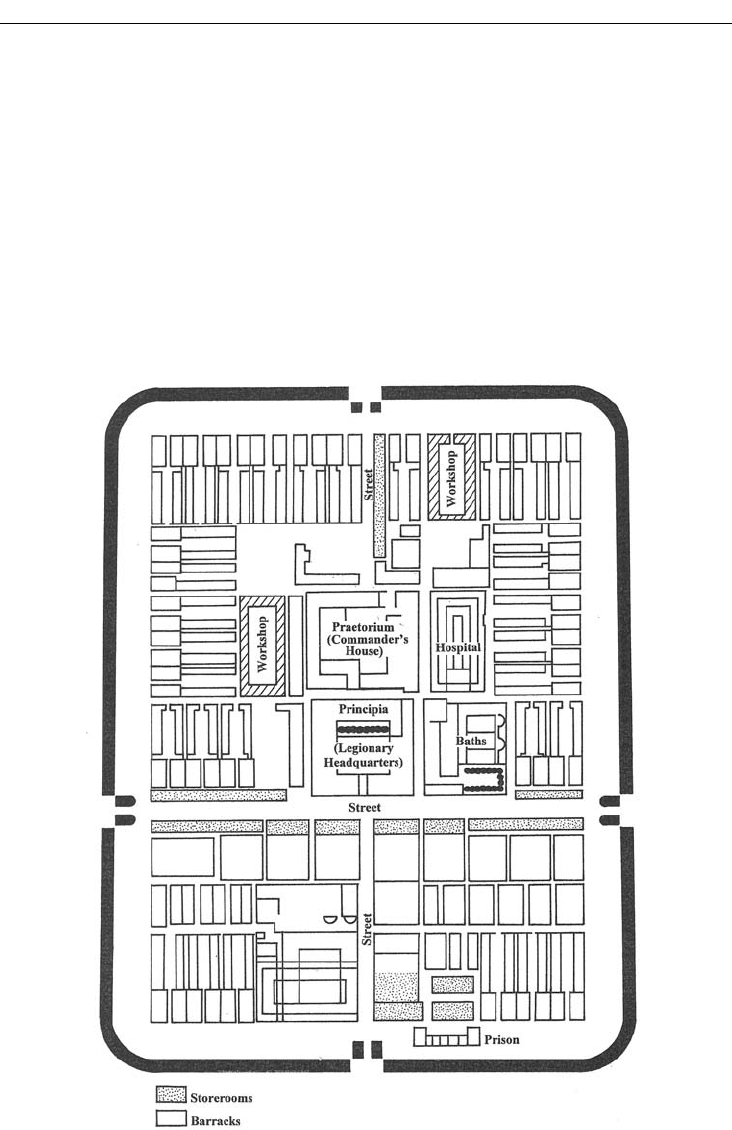

Army camps (Latin castrum, pl. castra) were established throughout Roman territory, but especially

in frontier zones. The layout of these camps utilized a standard plan, a square with straight streets

crossing at right angles, with the commander’s tent placed in the center, soldiers’ barracks and

other facilities neatly arranged along the streets (Figure 20.3). These camps closely resembled

Figure 20.3 Diagram, legionary fort, Novaesium, on the Rhine frontier in Lower Germany

ROME TO THE END OF THE REPUBLIC 335

plans for newly founded towns. Indeed, Greco-Roman city plans featuring the Hippodamian

grid must have influenced camp layout – and camp layout in turn influenced town plans. The

camps themselves often developed into permanent towns, such as Eboracum (modern York,

England), Colonia Agrippina (Cologne, Germany), and Augusta Praetoria (Aosta, Italy).

Castra could be either “marching camps” for overnight stays, or permanent forts. Polybius, the

Greek historian of the second century BC, has left a clear description of how a marching camp

was set up. First, the standard was planted to mark the site of the commander’s tent. Around this

the rest of the camp was then laid out in regular fashion, with a margin of empty space left by the

outer walls, space for mustering soldiers, for drills, for assembling cattle and booty, and to serve

as extra space that enemy fire would have to cross.

Colonies: early Ostia

The Roman colonia differed from the Greek colony in that it was not a regular settlement autono-

mous from the mother city that founded it, but a town initially established in order to assure military

control or political domination of a region, both on land and (in coastal locations) on sea. Ostia, later

developed as the port of Rome, was one of the earliest such colonies, founded in the mid-fourth

century BC at the mouth of the Tiber to control maritime and river traffic and to protect Rome

against incursions by sea. Laid out as a military camp, although rectangular (measuring 194m ×

125m), not the usual square, Ostia had the standard features of two bisecting main streets, the cardo

(north–south) and the decumanus (east–west), with a forum where they crossed. In later centuries,

as the Romans consolidated their control in Italy, the need for fortified camps in the Italian peninsula

diminished. A town might then safely expand beyond the original confines of the camp, as indeed

happened at Ostia by the first century BC (for the later development of Ostia, see Chapter 22).

In the later Republic and during the empire, colonies were established to relieve population

pressure in large cities, and to reward veterans with gifts of free land, sometimes confiscated

from previous owners. The size of colonies varied in population, from a few hundred families to

several thousand, and in territory as well, including both the urban center and farmland.

Their government imitating the institutions of Rome itself, colonies were controlled by a

council (or senate) and officials (magistrates). Likewise civic buildings recalled those seen in the

capital, such as the temple to the three gods Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva; and the curia (meeting

place of the Senate), the comitium (meeting place of the Assemblies), and the basilica (law courts;

miscellaneous business matters). Deliberately placed in frontier zones or in conquered lands,

such cities extended the patterns of Roman urban life to the diverse peoples of the empire.

The colonia was officially established according to a fixed routine. First came religious rites, attrib-

uted by the Romans to Etruscan practice. A ritual boundary line, the pomerium, was ploughed by a

bull and cow yoked to a bronze plough. At the streets or gates, the plough was lifted up and replaced

on the other side. After this, the land for the colonia was surveyed in a process called centuriation

by a team of professional surveyors who used in particular the groma, an instrument with two bars

crossing at right angles and plumb lines, with which right angles and their straight extensions could

be determined. The land was divided into quadrants by the cardo and the decumanus, and then into

long narrow units. The basic measure of land was the century (centuria, in Latin), ca. 50ha, itself consist-

ing of 100 heredia. One heredium, ca. 0.50ha, the usual plot assigned to one particular farmer or family,

was considered the amount of land necessary for a family to support itself. Marble fragments of a

map of

AD 77 recording individual centuriae, numbered and with the owners and tax rates listed, have

survived from the city of Arausio (modern Orange) in southern France. Typically, a bronze copy of

this information would be displayed in the local town hall, with a linen copy forwarded to Rome.

336 ANCIENT ITALY AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE

COSA, A TOWN OF THE ROMAN REPUBLIC

Despite the interest of Ostia and the importance of Rome itself, well documented in literary

sources, later construction in these long-lived cities has destroyed or damaged the remains from

the Republican centuries. The fragments from Rome are too important to ignore, however, and

we shall examine them shortly. But first let us visit a Republican town that can be appreciated in

its entirety: Cosa, a colonia founded in 273 BC, implanted in territory conquered from the Etrus-

can city of Vulci, strategically placed to block Etruscan access to the sea. Like Priene (Chapter

17), this town owes its importance in modern archaeology to its modest destiny in antiquity. Cosa

was sacked in 70–60 BC, perhaps by pirates; subsequent occupation was modest. Medieval and

modern times passed it by. Because the town is mentioned only briefly in ancient literary sources,

our knowledge of Cosa depends on the excavations conducted in the years 1948–54 and 1965–72

under the direction of Frank Brown of the American Academy in Rome.

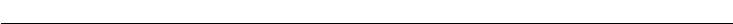

The town occupied an area of 13.25ha on a hill by a good harbor 140km north of Rome. The sur-

rounding farmland was fertile, and in fact most Cosans (90 percent of the citizens) lived outside the

walled town. A lagoon behind the harbor gave rise to a prosperous local industry, a fishery with a spe-

cialty in eels and mullets, and perhaps production of garum, a fish sauce much loved by the Romans.

The citadel, known as the Arx, occupied the town’s highest point. The Romans planned the rest

of the town from sitings taken here. The city walls were erected first, an irregular perimeter just under

2km in length, with three gates, one postern, and eighteen towers. Measuring 2m in thickness, of

irregularly shaped blocks of hard limestone, these sturdy walls are still well preserved to a height of

9m–10m. Despite the varying contours of the site, the space inside was laid out in a regular grid (Fig-

ure 20.4), a determined imposing of order on unruly nature that recalls urban planning at Priene.

Figure 20.4 City plan, Cosa

ROME TO THE END OF THE REPUBLIC 337

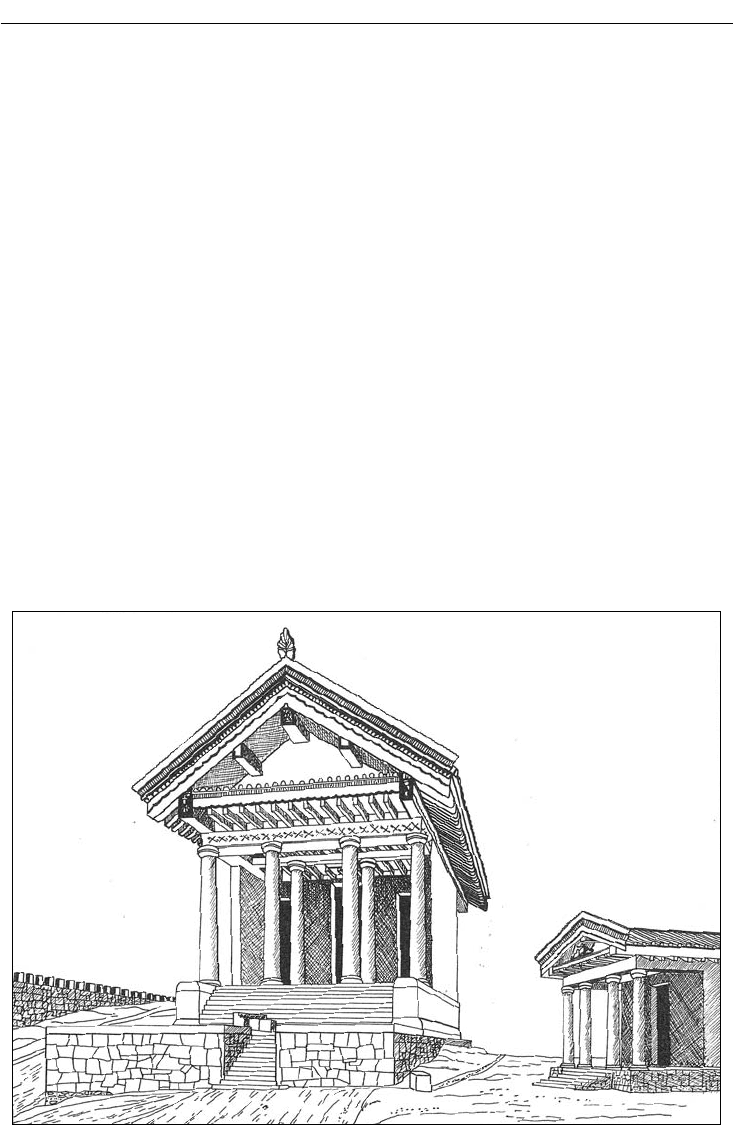

The Arx, protected with its own set of fortification walls, contained the principal shrine of

the town, the Temple of Jupiter with, in front, a cistern and a court with an altar. As at Rome,

the area sacred to Jupiter lay on high ground. The temple stood on a high podium; in plan, the

temple contained a front porch, with four columns, and the usual triple cella. The superstructure

has been reconstructed on the basis of terracotta fragments of architectural decorations, with

help from comments of Vitruvius (Figure 20.5). The temple was originally built after 241 BC, then

rebuilt ca. 150 BC, with the varying styles of its terracotta decorations suggesting a lengthy period

of refurbishing and repair.

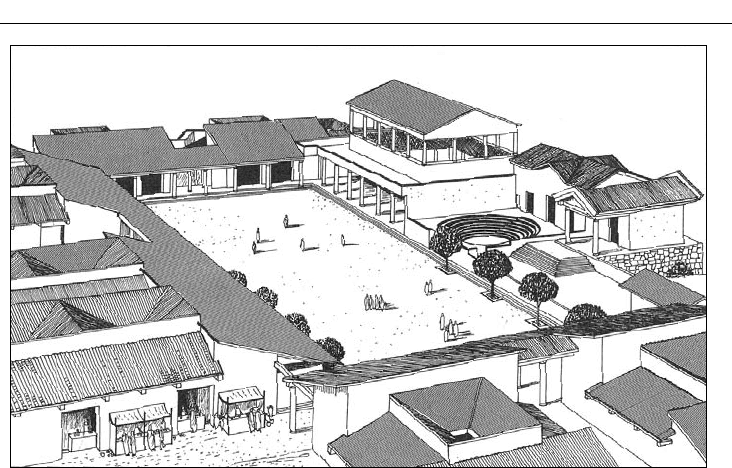

A major street led directly from the Arx downhill to the other important sector of the town,

the forum, or city center, a rectangular space lined with buildings devoted to civic functions (Fig-

ure 20.6). By the later third century BC, such buildings included the comitium, the meeting place

of the assembly of the people, here a circular open-air area with steps, and behind it, the curia, a

covered rectangular hall, the home of the local senate, or council of elders. A shrine and a prison

flanked the comitium on one side, a cistern on the other. In the second century BC, additions

included a commemorative triple arch at the north-west entrance to the forum and a basilica

erected over the cistern. Archive and office buildings lined the rest of the forum.

The basilica is a building type that became common in the Roman world from the second

century BC. In the fourth century AD, the basilica plan was adapted as the standard design for

Christian churches. Not a religious building in Roman times, the basilica provided space for law-

yers, judges, and other officials involved in city and legal affairs. It was always located alongside

a forum or a similar open space, with one of its sides penetrated by doors. The basilica typically

Figure 20.5 Arx Temples: Capitolium and Mater Matuta (reconstruction), from Cosa

338 ANCIENT ITALY AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE

consists of a central rectangle, roofed, surrounded by a peristyle and walkways, also covered,

on all four sides. The central roof rises higher than that over the side halls. This raised roofline

allowed for a line of windows, an architectural arrangement known as a clerestory (used in the

Hypostyle Hall, Delos: Chapter 18).

Arches, vaults, concrete, and concrete facing

In the north-west entrance into the forum lie the ruins of a triple archway, one of the earliest

Roman examples of the voussoir arch, or true arch. Perhaps invented in the Near East, used rarely

in fourth century BC Greek and Etruscan architecture, the true arch would become a hallmark

of Roman architecture. The true arch is made of voussoirs, wedge-shaped stones that direct the

pressure from the weight of the stones to the side as well as directly down (see Figure 2.18a).

The arch is a two-dimensional form. When continued in three dimensions, it becomes a barrel

(or tunnel ) vault (Figure 2.18b). Other types of vaults were also used in Roman architecture, nota-

bly the groin vault, the result of the intersection of barrel vaults (Figure 2.18c).

In Cosa’s triple archway, mortared rubble is one element used in its construction, an early use

of concrete. Concrete is a mixture of lime, sand, and water, a combination that makes a sort of glue

with the property of hardening well. By the time of Augustus, the Romans habitually included as

well volcanic dust from Etruria-Latium-Campania, a dust called “pozzolana” after the town of

Pozzuoli (ancient Puteoli) on the Bay of Naples. This compound produced a particularly strong

concrete which had the added virtue of being hydraulic: it could set underwater, and so could be

used for harbor foundations and as an impervious lining for aqueducts and cisterns. Concrete

would also be mixed with an aggregate, such as rubble – small irregular stones – to make the core

of a wall. Like the true arch, concrete would become a characteristic feature of Roman architec-

ture: a miracle substance that would permit during the imperial period an astonishing array of

architectural forms that departed radically from traditional Greek and even Italic practice.

Figure 20.6 Forum, sixth phase (reconstruction), Cosa

ROME TO THE END OF THE REPUBLIC 339

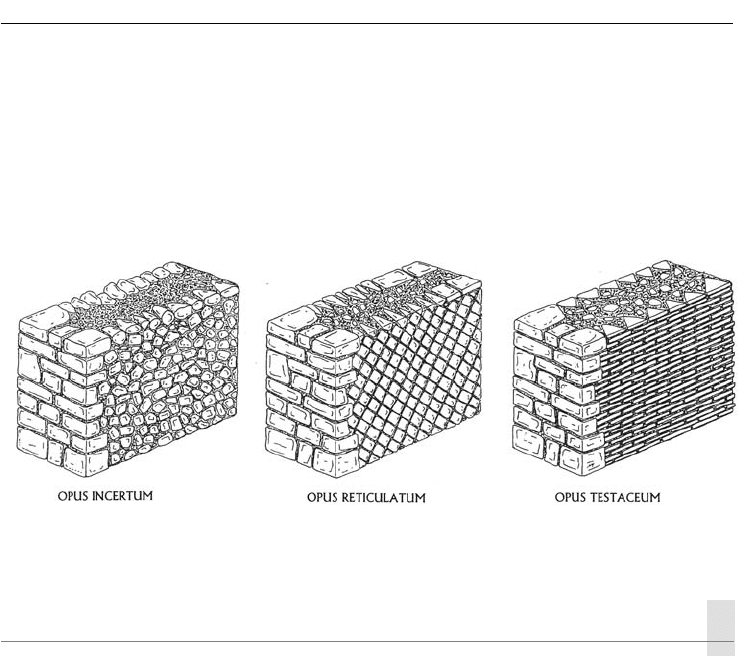

A concrete core of a structure would normally be faced with cut stones or brick, to give a

regular appearance to the exterior (Figure 20.7). Well-known patterns of facings include (1) opus

incertum, small stones of irregular shape; (2) opus reticulatum, small stones cut with a square face,

placed in a diamond pattern; and (3) opus testaceum, a facing of bricks or tiles. The first was popular

in the second and early first centuries BC, the second especially in the first century BC and the first

century AD, and the third from the mid-first century AD on. An elegant facing could be provided

by marble revetments, thin slabs of marble. Marble was expensive, however, because it had to be

imported from distant sources in northern Italy or the Aegean region.

ROME DURING THE REPUBLIC

The excavations of Cosa give a picture of the overall aspect of a town of the Republican period,

with walls, a grid plan, citadel, forum, and even private houses, and information on its economy (its

port and lagoon, and farmlands). But to what extent does this reflect the situation of Rome itself?

The 500 years of the Republic witnessed a tremendous development in the capital city. Assess-

ing the growth of Rome in these centuries is difficult, because architectural remains tend to

be fragmentary, damaged or destroyed by construction activity in later imperial times. Literary

sources, however, provide indispensable help for understanding the appearance and function-

ing of the city. What seems clear is that during the later Republic the city of Rome assumed

its characteristic form, with most standard building types introduced then. Many stood in the

Roman Forum; our survey of the Republican capital will thus concentrate on that central place

of the city. We shall see that the buildings at Cosa represent a distillation of the civic architecture

of Rome. The orderly layout of Cosa is not, however, copying a precedent from the capital city,

which grew organically over many centuries, but instead derives from its foundation at a precise

moment in time.

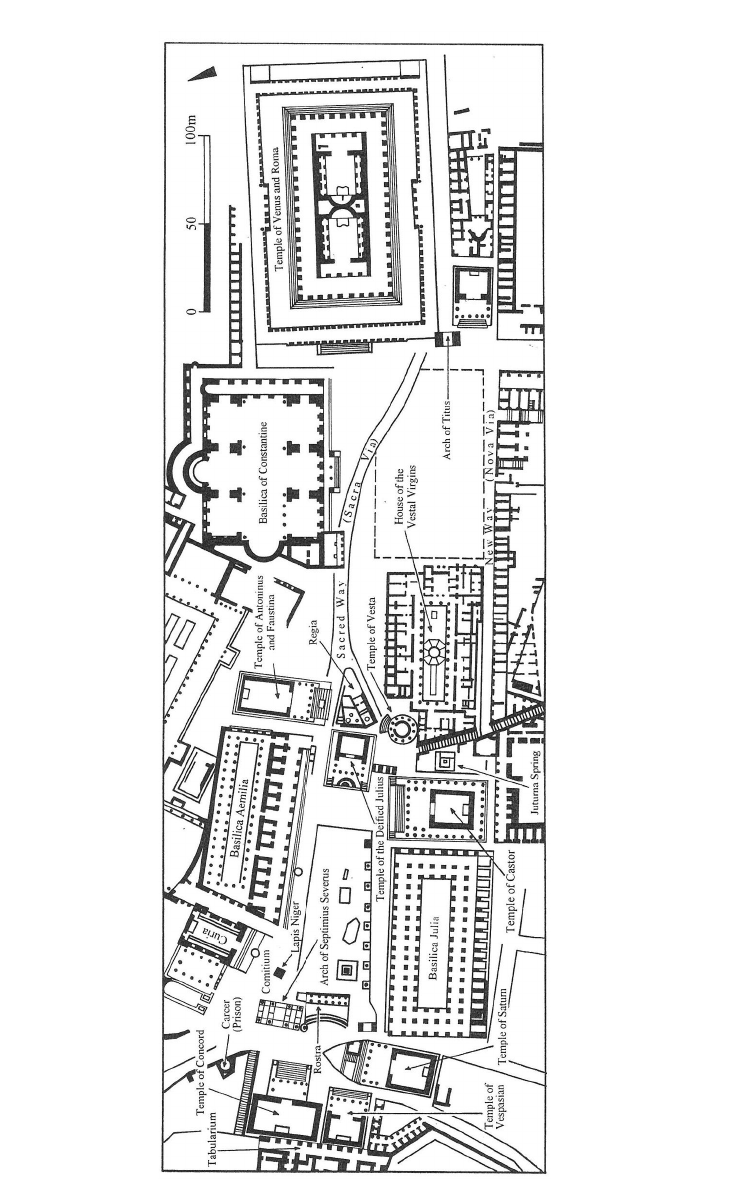

The Roman Forum (Forum Romanum)

The low ground to the north of the Palatine Hill and to the east of the Capitoline Hill served

from early times as the civic center of the city of Rome (Figure 20.8). Because of centuries of use

and modifications, the building history of the area is extremely complicated. Until early modern

times, the area was covered with houses and served as an integral part of the city. Antiquarian

Figure 20.7 Three types of Roman wall facing: opus incertum, opus reticulatum, and opus testaceum

340 ANCIENT ITALY AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE

interest intensified in the early nineteenth century, with systematic excavation beginning in 1870.

Further stimulus for exploration came during the dictatorship of Benito Mussolini, 1922–43, in

his drive to link Fascist Italy with the glories of ancient Rome. Work continues today, with atten-

tion to problems of preservation in the heart of a large congested city.

This land was originally marshy, crossed by streams. To render the area useful, the streams

needed to be chaneled. And indeed, the Etruscan kings did just that, according to Livy. A sewer,

the cloaca maxima, was built across the area for the evacuation into the Tiber River of stream

and rainwater and liquid wastes; eventually it was lined with stone and vaulted with concrete, an

impressive construction that measured ca. 2.0m–4.5m wide, 2.7m–4.2m high.

During Republican times, the forum consisted of an irregular rectangle, with its corners at the

Curia, the site of the later Temple of Antoninus, the Temple of Castor, and the Temple of Saturn

(see Figure 20.8). Leading into the forum was the Sacred Way, an old street whose existence

indicates the intertwining of religious and civic here at Rome as already seen in Athens and the

Ancient Near East. Like the Athenian Agora, the Roman Forum developed over many centuries,

with buildings placed here and there, as the need arose, not in an ordered arrangement. This

haphazard development contrasts with that of the forum at Cosa and with the later Imperial

Fora of Rome itself.

Religious buildings

Religious buildings in the forum included three major temples to the deities Vesta, Saturn, and

Castor, and an important shrine, the Lacus Iuturnae. Vesta was the goddess of the hearth. Her

temple contained not a cult statue, but instead the sacred hearth fire of the state; the hearth

and its fire were symbols central to Roman religion. The temple itself was round. Originally it

resembled an Iron Age Italic hut with a thatched roof. But the building was repeatedly destroyed,

damaged by fires, and rebuilt many times; its final version, erected by Julia Domna, the wife of

Septimius Severus, in the late second century AD, was an elegant marble tholos surrounded by

twenty columns with Corinthian capitals.

The original Temple of Saturn dated from the early Republic, but the extant remains are from

a rebuilding in 42 BC and later refurbishing (after a fourth-century AD fire). The temple stands on

a high podium, in typical Italic style. The temple contained the state treasury. Saturn himself was

a god of agricultural fertility and indeed of civilized life. His cult statue, made largely of ivory, was

filled with vegetal oil, a fruit of his magnanimity.

The last of these deities, the divine twins Castor and Pollux, were honored twice in the forum.

According to legend, Castor and Pollux helped the Romans defeat the Latins at the Battle of

Lake Regillus in 496 BC. After the battle they were seen watering their horses at the Juturna

Spring (Lacus Iuturnae). These divine protectors received early tributes in the Roman Forum. At

the spring, a stone fountain building was erected in their honor. Nearby, a Temple to Castor (and

perhaps Pollux) was built. The visible ruins come especially from the rebuilding in the Augustan

period: the temple stood on a high podium, but otherwise was largely Greek in feel, with a peri-

style of Corinthian columns around all four sides.

Civic buildings

The forum contained many structures that served governmental and other civic functions. The

Regia, a small building, was the headquarters of the pontifex maximus, the head of the state religion.

The Senate met in the Curia; this meeting hall underwent various reconstructions, the pres-

ent building having been erected by Diocletian after a fire of

AD 283, but based on the version

Figure 20.8 Multi-period plan (through the early fourth century AD), Forum Romanum, Rome