Holford Matthew, Stringer Keith. Border Liberties and Loyalties in North-East England, 1200-1400 (ENG)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

BORDER LIBERTIES AND LOYALTIES

356

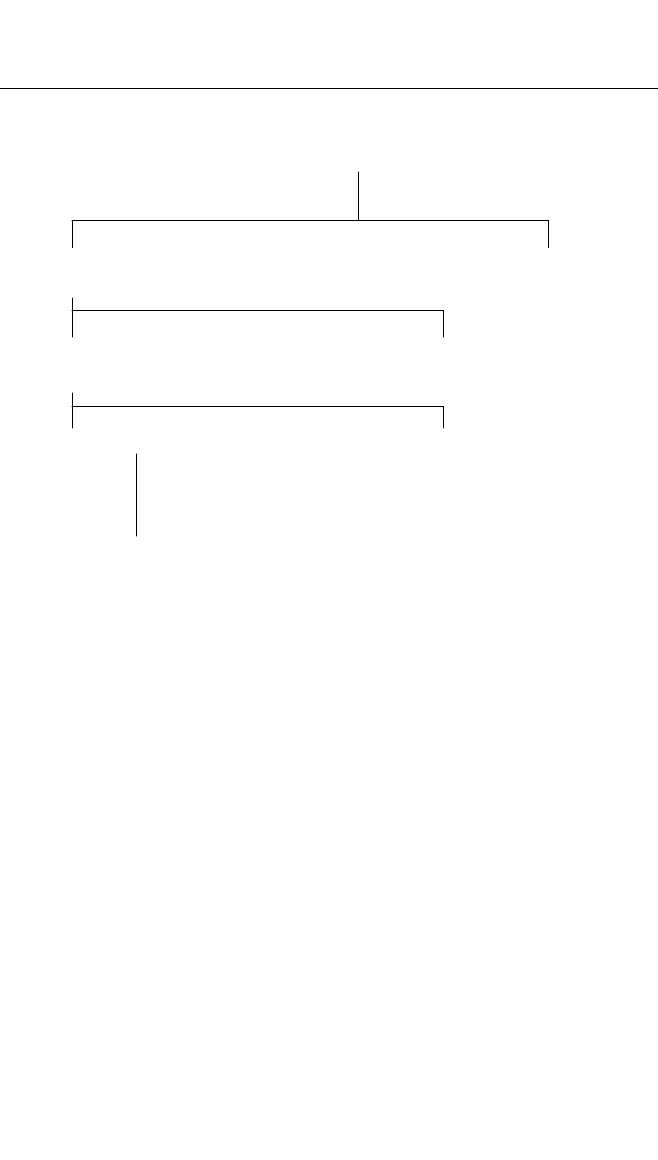

Table 1 Swinburne of Haughton, Capheaton

(simplified)

Main estates by c. 1300: Haughton (one-third of township) and Williamston, Tynedale; Capheaton

and Chollerton, Prudhoe barony; Raylees, Redesdale.

William I Swinburne

treasurer of Queen Margaret of Scotland

d. 1289

Alexander

. 1310

William II

. 1354

Christiana = John Thirlwall

the younger

Catherine = John Haltwhistle

Nicholas

(of Staward)

William III = Joan, dau. of

d. c. 1360 Robert II Ogle

William IV = Mary, dau. of Alan Hetton

d. 1404

M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 356M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 356 4/3/10 16:13:024/3/10 16:13:02

TYNEDALE: A COMMUNITY IN TRANSITION

357

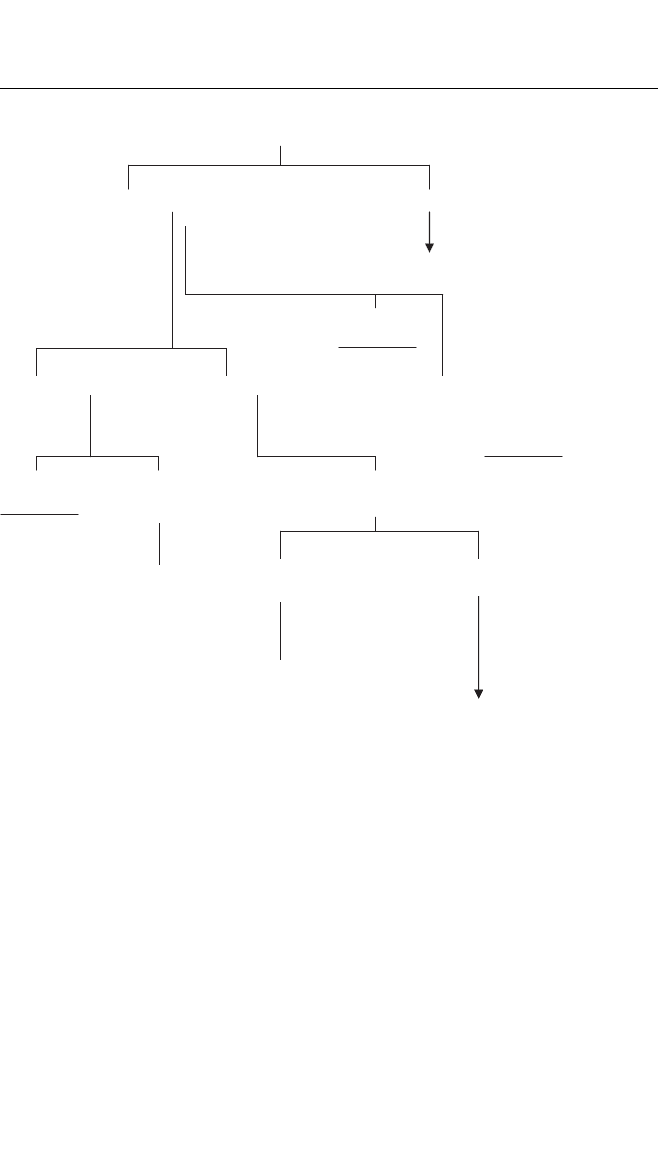

Table 2 Swinburne of Haughton, Little Swinburne

(including Heron, Stirling and Widdrington; simplified)

Main estates by c. 1300: Haughton (two-thirds of township), Humshaugh and Simonburn, Tynedale;

Little Swinburne, Bywell barony; Bewcastle, Irthington and Lanerton, Cumberland. For the shares of

Heron, Stirling and Widdrington, see CCR 1327–30, p. 8.

John Swinburne

d. c. 1313

Adam = (1)

d. 1318 = (2) Idonea Graham

Robert I

Henry

d.s.p. 1326

Gerard

d.s.p. 1362

Roger

d. 1372

John

d. 1444

Roger

d. c. 1395

William

d. c. 1400

Walter

d. c. 1390

William

d. 1379

Swinburne of Knarsdale, Little Horkesley

Christiana = John

Widdrington

d. c. 1305

Elizabeth = Roger

Heron

d. 1333

Barnaba = (1) John Middleton

executed 1318

= (2) John Stirling

d.s.p. 1378

Heron

of Chipchase

M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 357M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 357 4/3/10 16:13:024/3/10 16:13:02

BORDER LIBERTIES AND LOYALTIES

358

Table 3 Swinburne of Knarsdale, Little Horkesley

(simplified)

Main estates by c. 1320: Knarsdale and Chirdon, Tynedale; Gunnerton, Bywell barony; Newbiggin,

Cumberland; Askham, Westmorland; Woodmancote, Gloucestershire; and (in expectancy) Wiston,

Suffolk, and Little Horkesley, Essex: CIPM, vi, no. 693; vii, nos. 452–3.

Robert I Swinburne = Margaret, dau. of Thomas Hillbeck

d. 1326

Thomas I

d. c. 1330

Adam

(of Duxford)

Robert II = (1) Agnes, dau. of William Felton

d. 1391 = (2) Joan, great-gddau. of John Botetourt

Thomas II = Elizabeth, wid. of Thomas Trivet

d.s.p. 1412

M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 358M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 358 4/3/10 16:13:024/3/10 16:13:02

359

8

Redesdale

Keith Stringer

M

edieval Redesdale is the poorest documented liberty to be consid-

ered in this book, and no study can expect to provide a fully rounded

analysis of its governance and society.

1

But we can, and indeed must, begin

with its geographical structure and setting. Redesdale was a compact ter-

ritorial unit of some 200 square miles. It shared with Tynedale a boundary

of twenty- two miles from the lower reaches of the Rede to Carter Fell. The

northern limits followed the Border as it twisted through one of its most

desolate stretches to Plea Knowe. On the east, Redesdale was divided from

Kidland and Coquetdale by a march that came down from the Cheviot

watershed and ran along the Coquet to Harehaugh opposite Hepple. The

bounds continued south by Steng Cross to the Ottercops Burn, and then

extended west towards Tynedale until the Rede was reached near its con-

fluence with the North Tyne.

2

In terms of modern parishes, the liberty

encompassed the whole of Corsenside, Elsdon, Otterburn and Rochester,

much of Alwinton, Harbottle and Hepple, and part of Birtley. Its medieval

ecclesiastical structure was based on the parish churches of Corsenside,

Elsdon and Holystone; its administrative townships for purposes of

royal taxation from 1336 were Chesterhope, Elsdon, Harbottle, Linshiels,

Otterburn, Troughend and Woodburn.

e liberty’s geography deeply in uenced its history and experiences.

It is plausible to suggest that a unitary block of territory entailed enhanced

possibilities for lordly power and local solidarity; but in Redesdale’s case the

reality was rather di erent. In 1220 the castle of Harbottle was described as

situated in the March of Scotland towards the ‘Great Waste’.

3

ough this

1

Original material for Redesdale was published by John Hodgson, notably in HN, II,

i. Otherwise the main contribution has been made in NCH, xv (by Madeleine Hope

Dodds), under ‘Holystone Chapelry’, which covers the north- eastern part of the

liberty.

2

Redesdale’s bounds have been reconstructed by comparing the circuit of 1604 in Survey

of the Debateable and Border Lands, etc., ed. R. P. Sanderson (Alnwick, 1891), pp. 84–5,

with a range of earlier sources.

3

Royal Letters, i, no. 122.

M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 359M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 359 4/3/10 16:13:024/3/10 16:13:02

BORDER LIBERTIES AND LOYALTIES

360

was a reference to the Cheviot massif, the description would not have been

out of place for Redesdale itself. Much of the terrain rises above 1,000 feet, and

there are few expanses below 600 feet. Accordingly it was (and is) a markedly

di erent environment from Northumberland’s domesticated lowlands. In

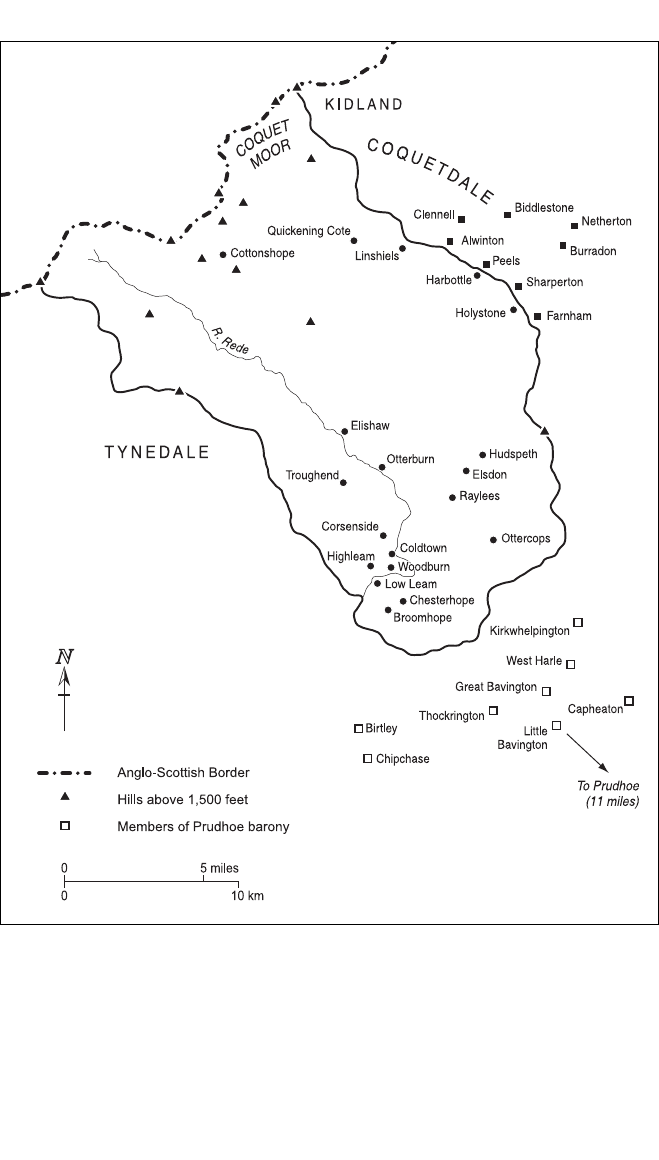

Map 6 The Liberty of Redesdale

M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 360M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 360 4/3/10 16:13:024/3/10 16:13:02

REDESDALE

361

1307, for example, twenty- four vaccaries (cattle farms) accounted for three-

quarters of the liberty- owner’s estimated annual income.

4

e arable areas

were almost entirely con ned to small concentrations close to the liberty–

county boundary; upper Redesdale was largely given over to shielings or

summer grazing grounds, and to seasonal occupation.

5

Such a pattern of

socio- economic organisation already indicates that ‘lordship’ and ‘society’

might have limited meanings in a Redesdale context. Moreover, while the

panorama from near Newcastle suggests a secluded, self- contained march-

land, the liberty was traversed by Dere Street, the main Roman road into

Scotland; another route ran up the Rede valley from Elishaw near Otterburn

to Redeswire (Carter Bar).

6

Redesdale’s heartlands thus lay within a day’s

ride of Jedburgh; Newcastle itself was as close to hand, and Corbridge,

Morpeth and Alnwick were closer still. By these measures, Redesdale was

scarcely a closed world; and its proximity both to Scotland and to the nodal

points of ‘county society’ had wide consequences for authority, governance

and ‘community’.

roughout our period Redesdale was held by the Umfraville family,

whose role is no less basic to an understanding of the liberty’s history.

7

At

the start of the thirteenth century, it was one of the oldest and most power-

ful noble houses in northern England. e rst Umfraville lord had been

established in Redesdale, and in the adjacent barony of Prudhoe, probably

through the favour of Henry I (1100–35); and it was not until the death of

the Garter knight Robert Umfraville in 1437, when the male line became

extinct, that Redesdale slipped from the family’s grasp. Its remarkable lon-

gevity ensured that Redesdale avoided the rapid turnovers of ownership

that o en disrupted the development of other secular liberties. Even so, the

continuity of Umfraville leadership was periodically undermined by lengthy

minorities and other dynastic di culties. Nor was the family consistently

successful in broader spheres. It sought to reinforce its regional dominance

and to strut on the larger ‘British’ stage; but the outbreak of Anglo- Scottish

warfare in 1296 played havoc with its status and ambitions. e family lost

its Scottish lands, and its Northumbrian territories were exposed to regular

harryings. War also assisted the advancement of a new court- connected

Border nobility, whose emergence caused further problems. Indeed, the

4

C 134/2/21; HN, II, i, pp. 108–9 (to the nearest pound, £142 out of £181).

5

See especially A. J. L. Winchester, The Harvest of the Hills (Edinburgh, 2000), pp. 85–91.

6

G. W. S. Barrow, ‘The Park in the Middle Ages’, in J. Philipson (ed.), Northumberland:

National Park Guide (London, 1969), p. 59.

7

Basic information on the Umfravilles is drawn without further reference from GEC, i, pp.

146–52; vii, pp. 355–7, 363–5; G. W. Watson, ‘The Umframvilles, earls of Angus and lords

of Kyme’, Genealogist, new ser., xxvi (1910), pp. 193–211; W. P. Hedley, Northumberland

Families (Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle upon Tyne, 1968–70), i, pp. 208–15.

M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 361M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 361 5/3/10 09:53:515/3/10 09:53:51

BORDER LIBERTIES AND LOYALTIES

362

rise of the Percy dynasty at the expense of the Umfravilles is a leitmotif of

the historiography of medieval Northumberland.

8

ere is much more to

their story than this; but, in one way or another, their fortunes and mis-

fortunes had profound repercussions for Redesdale as both a liberty and a

society.

At this juncture, it will therefore be helpful to consider more closely the

8

For instance, J. A. Tuck, ‘The emergence of a northern nobility, 1250–1400’, NH, 22

(1986), pp. 1–17.

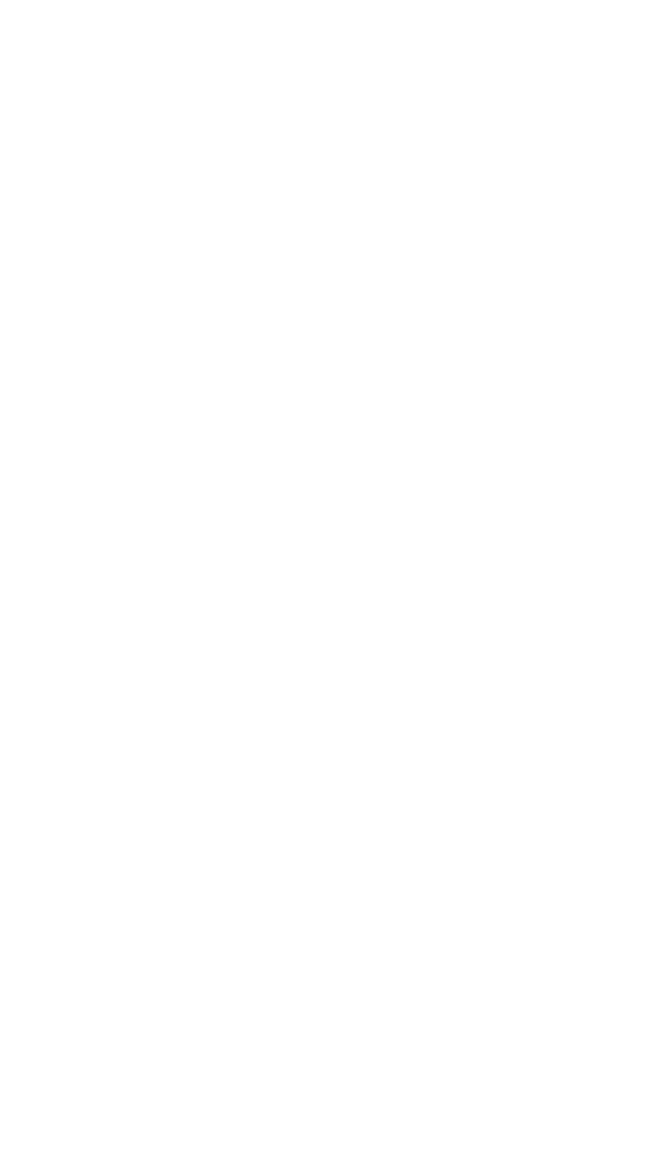

Table 4 Umfraville of Redesdale

(simplified; earls of Angus shown in capitals)

Richard Umfraville

d. 1226

GILBERT I = (2) Maud, suo jure countess of Angus

d. 1245

GILBERT II = Elizabeth, dau. of Alexander Comyn, earl of Buchan

d. 1307

ROBERT = (1) Lucy, dau. of Philip Kyme

d. 1325 = (2) Eleanor (Clare?)

GILBERT III = (2) Maud, sis. of Anthony Lucy

d.s.p. 1381

Thomas I

d. 1387

Thomas II

d. 1391

Robert

d.s.p. 1437

Gilbert ‘earl of Kyme’

b. 1390

d.s.p. 1421

M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 362M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 362 5/3/10 09:53:515/3/10 09:53:51

REDESDALE

363

overall nature and dynamics of Umfraville power with particular refer-

ence to the thirteenth century, which was an important era of expansion

and consolidation. e ability of Gilbert I Umfraville to maintain Scottish

friendships – his father Richard had supported Alexander II against King

John – paid o handsomely when in 1243 he secured the earldom of Angus

by marriage. Comital rank elevated the Umfravilles to a new plane of pres-

tige and authority; and they were to parade the title ‘earl of Angus’ long a er

Angus had been taken from them as a forfeit of war. Yet their core interests

remained focused on Northumberland; it was thus essentially as Border

lords that they asserted their identity and a rmed their pre- eminence.

Angus was a er all one of Scotland’s smallest earldoms, with an income of

£80 in 1264. By contrast, the Northumbrian estates, valued at some £333 in

1256, placed the family at the forefront of the north- eastern nobility, as was

fully appreciated by Simon de Montfort, who snapped them up with the

wardship of Gilbert II Umfraville in 1245.

9

In terms of the Umfravilles’ thirteenth- century regional hegemony, the

most obvious development concerned Redesdale itself, whose jurisdictional

rights were clari ed and more rigorously exploited. But we cannot assume

that the liberty was the family’s paramount source of wealth and political

in uence. On Earl Gilbert II’s coming of age in 1266, Redesdale had long

been part of an interlocking complex of lands and lordship, and not nec-

essarily the most prized part. Admittedly it was more focal to Umfraville

power- building than were the so- called ‘ten towns of Coquetdale’: namely,

Alwinton, Biddlestone, Burradon, Clennell, Farnham, Netherton, Peels,

Sharperton and (in the Breamish valley) Fawdon and Ingram. ese vills,

eight of which nestled on the liberty’s eastern ank, had been held by the

Umfravilles since Henry I’s reign as mesne tenants of the lords of Alnwick;

but little property was retained in demesne.

10

Far more signi cant, however,

was the lowland barony of Prudhoe, whose patchwork of manors – includ-

ing Rudchester, Ingoe, Chipchase, Birtley, Capheaton, West Harle and

Kirkwhelpington – extended northwards from the Derwent and the Tyne

to Redesdale’s southern boundary. In 1245 the barony and the liberty,

including advowsons, were valued at about £289 and £180 respectively.

is helps to explain why the castle of Prudhoe was well established as the

family’s main lordship centre by 1200.

11

King John acknowledged as much

when in 1212 he required Richard Umfraville to surrender it as security

9

The Exchequer Rolls of Scotland, ed. J. Stuart et al. (Edinburgh, 1878–1908), i, p. 9; NAR,

p. 102; J. R. Maddicott, Simon de Montfort (Cambridge, 1994), p. 54.

10

NCH, xiv, pp. 472–3, 477–80; xv, pp. 405–47, passim.

11

CDS, i, no. 1667; L. Keen, ‘The Umfravilles, the castle and the barony of Prudhoe,

Northumberland’, Anglo- Norman Studies, 5 (1982), pp. 165–84.

M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 363M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 363 4/3/10 16:13:024/3/10 16:13:02

BORDER LIBERTIES AND LOYALTIES

364

for his good behaviour; and, to anticipate, when the Percies moved in on

Umfraville territory in the late fourteenth century, it was the barony of

Prudhoe that they coveted above all else.

12

Moreover, when the Umfravilles had a choice in the matter, it was the

barony rather than the liberty that tended to be protected from family set-

tlements and other inroads. Around 1220, for example, Richard Umfraville

allocated large properties in Redesdale to his daughter Sibyl and her

husband, Hugh Morwick, to prevent them from tying up lands near

Prudhoe. Dowagers had Otterburn settled on them for a residence; while in

1331–2 Earl Gilbert III would go to considerable lengths to keep Prudhoe’s

assets out of the settlement for his step- mother by ensuring that the bulk of

her portion was assigned in the liberty.

13

Also revealing is the Umfravilles’

attitude towards Kidland. is expanse of hill country had been appropri-

ated from the ‘Great Waste’ in the twel h century; but it was not perma-

nently absorbed into Redesdale proper because of alienations in favour of

Newminster Abbey, a process that began in 1181 and ended in 1270, when

Earl Gilbert II sold to the monks the moors of Kidland ‘entirely, with all

their appurtenances and rights’.

14

Redesdale could still exercise an important in uence on the Umfravilles’

self- image and how they were seen by others. ey occasionally aired the

title ‘earl of Angus and lord of Redesdale’; more remarkably, it was not

unknown (a er 1296) for local scribes to refer to the ‘earl of Redesdale’.

15

Nor can it be gainsaid that the liberty’s administrative and judicial privi-

leges gave the lord a much ampler authority than he was entitled to enjoy

as baron of Prudhoe. Yet, as will shortly be underlined, Redesdale’s govern-

ance rights were de ned gradually; nor did it attain the autonomy and uni-

fying force of a ‘royal liberty’. Furthermore, in the thirteenth century (and

later) the Umfravilles needed little reminding that their claims to leadership

depended on mobilising the resources of all their Northumbrian domains,

and on reinforcing their mastery through ties of lordship and service within

the region generally. Even Redesdale’s internal governmental structure

bore witness to such priorities. e original administrative focus was the

earthwork castle in Elsdon; but by about 1200 it had been supplanted by

Harbottle castle, on the edge of the liberty in the Coquet valley, in order

12

J. C. Holt, The Northerners, new edn (Oxford, 1992), p. 83; below, p. 405.

13

Below, p. 380; CDS, i, no. 1668; BL, Harley Ch. 58.G.22; CCR 1330–3, pp. 454, 552.

14

Newminster Cart., p. 300. See further J. C. Hodgson, ‘The lordship of Kidland and its

successive owners’, AA, 3rd ser., 8 (1912), pp. 21–3; E. Miller, ‘Rowhope, Trows, and

Barrowburn’, and ‘Shilmoor’, PSAN, 5th ser., 1 (1955), pp. 270–1, 333–4.

15

NCS, ZSW/4/11; HN, III, ii, p. 1; BL, Harley Ch. 58.G.22; Notts. Archives, DD/FJ/4/26/13;

CCR 1337–9, p. 103; CDS, iii, no. 835; Newminster Cart., pp. 50, 159; Percy Cart., nos. 653,

677; Hexham Priory, ii, p. 37.

M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 364M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 364 4/3/10 16:13:024/3/10 16:13:02

REDESDALE

365

to project the lord’s authority over both Redesdale and the ‘ten towns’.

16

Such strategies con rmed Redesdale’s status as part of a wider framework

of power; they likewise promoted clientage networks encouraging closer

social integration with the county of Northumberland. And, aside from

other considerations, they were unlikely to forge a liberty and a ‘commu-

nity’ with their own well- de ned senses of identity and distinctiveness.

Since Redesdale’s history as a jurisdiction is little known, it is essential

to establish some of the institutional groundwork before we turn to the

socio- political realities. As might be expected, the precise nature of twel h-

century Redesdale’s governmental rights is unclear. Most frontier liberties

were originally personal or territorial superiorities; and the jurisdictional

architecture developed over time, o en in response to the threat posed by

the rise of the ‘law- state’ to the authority and ambitions of local lordship.

17

In 1212 it was reported that Redesdale was held in chief of the king ‘by the

service of defending it from thieves’.

18

is responsibility does not imply

any delegation of crown power, still less a historic ‘immunity’ from such

power. Rather, it suggests a general right to rule in a marchland beyond

the reach of regular crown government; and no doubt the lord’s author-

ity had been freely adapted to meet such conditions. Indeed, in 1279 Earl

Gilbert II would justify his right to gaol delivery at pleasure by appeal to the

powers assumed by his forebears ‘because the liberty is beside the March of

Scotland’.

19

Also instructive are the terms of the ‘Redesdale charter’. is

forgery, known only from a copy made by Roger Dodsworth in the 1630s,

was possibly concocted for Earl Gilbert during the Quo Warranto inquir-

ies, that is, before the crown conceded in 1290 that long usage (as opposed

to express royal sanction) could warrant ‘franchises’. e legitimating

discourse explains that the rst Umfraville lord of Redesdale gained it by

William the Conqueror’s grant; that it was acquired with the ‘royal rights’

enjoyed by its pre- Norman lord; and that it was to be held by the service of

securing it ‘from enemies and wolves’ with the sword worn by William on

his entry into Northumberland.

20

is communicates a version of the past

16

There is a good discussion of this matter in Elsdon, Northumberland: An Archaeological

and Historical Study of a Border Township (unpublished report, The Archaeological

Practice Ltd, Newcastle, 2004), pp. 33–6.

17

The classic study is R. R. Davies, ‘Kings, lords and liberties in the March of Wales, 1066–

1272’, TRHS, 5th ser., 29 (1979), pp. 41–61.

18

BF, i, p. 201.

19

NAR, p. 373.

20

On the ‘Redesdale charter’ and its provenance, see H. Pease, ‘Otterburn’, AA, 3rd ser., 21

(1924), pp. 124–6, supplemented by references showing that Earl Gilbert II held Redesdale

‘by the service of defending it from wolf and thief’ (CIPM, v, no. 47), and that it was fixed

M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 365M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 365 4/3/10 16:13:034/3/10 16:13:03