Johnston R.A. All Things Medieval: An Encyclopedia of the Medieval World

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Numbers

540

Liber Abaci is now most famous for presenting a medieval word prob-

lem. If a pair of rabbits produces one pair of offspring after one month, and

a month later both pairs each have produced another pair, and a month

later the rabbit pairs all have produced another pair, how many rabbits will

there be after one year? Fibonacci demonstrated a table of Arabic num-

bers that neatly predicted the rabbit numbers after one year, two years, or

any amount of time. The table’s pattern of numbers is still taught as Fi-

bonacci numbers, and the pattern also predicts patterns in nature, such

as the rate at which the swirls of a snail’s shell will enlarge as they travel

outward.

Around 1230, an English scholar, John of Holywood, wrote a Latin

book that explained the basics of Arabic arithmetic. Algorismus Vulgaris be-

came a standard textbook at universities. Arabic numerals were still not in

popular use, but thousands of students could learn the system.

Most Europeans had some objections to the new number system. The

concept of zero was diffi cult, since Roman numerals were primarily for

counting and there was no symbol for “nothing.” It was not easy at fi rst for

them to see why 50 was 10 times larger than 5 when it only had “nothing”

added to it. Italian bankers had been among the early acceptors of the sys-

tem, since it simplifi ed accounting. However, Arabic numerals were easier

to falsify, so, in 1299, the city of Florence banned their use. Many other

cities followed Florence’s lead and refused to use the new numbers in com-

merce or government.

During the 14th century, European scholars produced not only trans-

lations but also original works on theoretical mathematics. Around 1325,

Thomas Bradwardine wrote treatises in Latin, using Arabic mathematics,

that established the beginning of mathematical physics. A French scholar,

Johannes de Lineriis, invented the modern fraction, written as two num-

bers stacked vertically with a line between, around 1340. By the later 14th

century, theoreticians in European universities were working on concepts

of infi nity, exponents, and coordinate geometry.

The 15th century saw popular acceptance of the new numbers. Theoreti-

cal scholarly achievements advanced more. A Persian, Al-Kashi, computed

pi to 16 places around 1430. Even in the heart of Europe, the close of the

Middle Ages saw major advances as mathematics was applied to architec-

ture, art, and astronomy. By the end of the 15th century, some arithmetic

textbooks were intended for use outside the universities. They demon-

strated long division and multiplication, and some taught how to use the

new numbers in accounting. By 1500, Arabic numbers were fully in use in

commerce and in schools.

See also: Banks, Muslims, Universities.

Numbers

541

Further Reading

Berggren, J. L. Episodes in the Mathematics of Medieval Islam. New York: Springer,

2003.

Flusche, Anna Marie. The Life and Legend of Gerbert of Aurillac: The Organ-Builder

Who Became Pope Sylvester II. Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press, 2006.

McLeish, John. The Story of Numbers: How Mathematics Has Shaped Civilization.

New York: Fawcett Columbine, 1991.

Posamentier, Alfred S., and Ingmar Lehmann. The Fabulous Fibonacci Numbers.

Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 2007.

Sigler, Laurence. Fibonacci’s Liber Abaci. New York: Springer, 2003.

Young, Robyn V., ed. Notable Mathematicians: From Ancient Times to the Present.

Detroit: Gale Research, 1998.

P

Painting

545

Painting

Art in the Middle Ages was part of religious expression. Where we view art

itself as an end product, they viewed it only as a means to an end. For most

of the period, the goal of art was spiritual devotion. They believed that love

came from seeing and that people needed to see depictions of Jesus, Mary,

and other saints in order to love them.

Art could also be purely decorative, but it focused mainly on making

churches beautiful. Churches had as much art as they could fi nd in their

local culture, whether it was carved wood, carved stone or ivory, wall paint-

ings, gold or silver, sculpted fi gures, or embroidered hangings. Decorative

art reached a high level of sophistication by the end of the Middle Ages.

Byzantine art was primarily religious. Continuing a tradition from Chris-

tian Rome, art in Constantinople focused on mosaics and the stylized de-

votional paintings called icons. Icons were wood panel paintings that showed

Jesus and the saints, typically in somber colors, and often utilized gold leaf.

The gold leaf served as a shining halo around the head of a saint and some-

times as decoration on clothing. Faces and fi gures tended to be slender

and tall, eyes were large and dark, and mouths were rarely smiling. Western

Europe under the Franks borrowed its earliest ideas about art from visits

to Constantinople. Charlemagne’s chapel at Aachen had paintings, wood

carvings, and gold decoration in direct imitation of what his ambassadors

had seen in the East, and early medieval art copied from Charlemagne.

During the 11th, 12th, and 13th centuries—the period we call the Ro-

manesque—the object of the painter or sculptor was to create an image

that evoked emotion in the viewer. Often, the goal was religious devotion,

but some art was made to beautify a room or building. Realistic detail was

important, but only as it conveyed the meaning of the image accurately.

Figures could be out of scale to each other as long as the viewer could

tell what they were. Buildings could be shown unrealistically small for the

people who were walking into them as long as the picture made the story

clear. Colors had to be clear and bright, and certain colors were symbolic

of purity or royalty. Gold, applied to the image to make it shine, was very

important, and expensive materials made the picture better. There were ar-

tistic conventions for portraying clothing or body position, and, as long as

these conventions told the viewer what was happening, it was acceptable if

they did not look exactly like reality. Idea symbols, such as halos to show

holiness, were part of the images.

Medieval artists showed no awareness of different clothing or building

customs in different places or times. A medieval painting of Moses showed

him in a contemporary robe and hat, and depictions of Bible towns like Je-

rusalem or Jericho were identical to medieval European walled cities and

castles. Although they did not give their viewers any understanding of the

Painting

546

real world of the Bible, they created records for us of their contemporary

buildings, clothing, tools, and food.

Even during the Romanesque period, some artists achieved good pro-

portion or realistic detail. However, the value of art did not depend on ar-

tistic realism. The value of art was dependent on its content, its materials,

and its success in using artistic convention to convey the message.

In the 13th century, the goal of artistic work began to shift. Painting

technique improved after several centuries of stable apprenticeship train-

ing in the arts. Apprenticed painters began to practice fi gure drawing, and

individual artists emerged as more talented and skilled than others. More

materials were available: more painting tints, more kinds of stone or pot-

tery, and more possibilities in stained glass. Great realistic detail was possi-

ble, and it was more often sought and achieved during the Gothic period.

Gothic stained glass art, wall paintings, book illustrations, and sculptures

all improved dramatically. They still used bright colors and conventional

symbolism, but they began to use more individual detail. A row of ladies

could be posed in slightly differing natural poses, and their hairstyles would

not be identical. Figures were not as symmetrical. Faces had more indi-

vidual detail, and the drapery of robes, whether painted or carved, looked

more like the pull of gravity on real fabric.

In 14th-century paintings, scenery was more in proportion to the fi g-

ures; in a group of fi gures, some were layered behind the others to cre-

ate a realistic sense of depth. The chief artist of the 14th century was the

Florentine painter Giotto di Bondone, usually known as simply Giotto.

He painted panels and frescoes; he documented the legendary life of Saint

Francis of Assisi and painted many Bible scenes on the walls of the famous

Arena Chapel in Padua. He painted the fresco murals of Florence’s Peruzzi

and Bardi chapels. When Giotto died in 1337, Florence gave him a state

funeral, the fi rst time any artist had been honored this way.

Giotto’s ability with realism was strikingly better than the painters before

him. He painted buildings with three dimensions and a vanishing point, in-

stead of fl at like the 13th-century painters. Squares turned to trapezoids,

growing smaller with distance. Porches and eaves cast realistic shadows on

the walls. Faces are depicted at many different angles, from full face to full

profi le, and proper perspective and shadow were always maintained. Con-

temporary viewers wrote that Giotto’s fi gures were so close to life that they

seemed to breathe and move. Gold leaf, halos, and religious symbols were

still very important in the works of Giotto and his Gothic contemporaries.

After the Black Death plague of 1347–1350, art in Europe changed.

Many artists and their patrons had died, and all craft training, including

art, was disrupted. Society became preoccupied with death and, to some

extent, disillusioned with the offi cial church, which had not been able to

keep up with the people’s needs. Patrons began to commission portraits

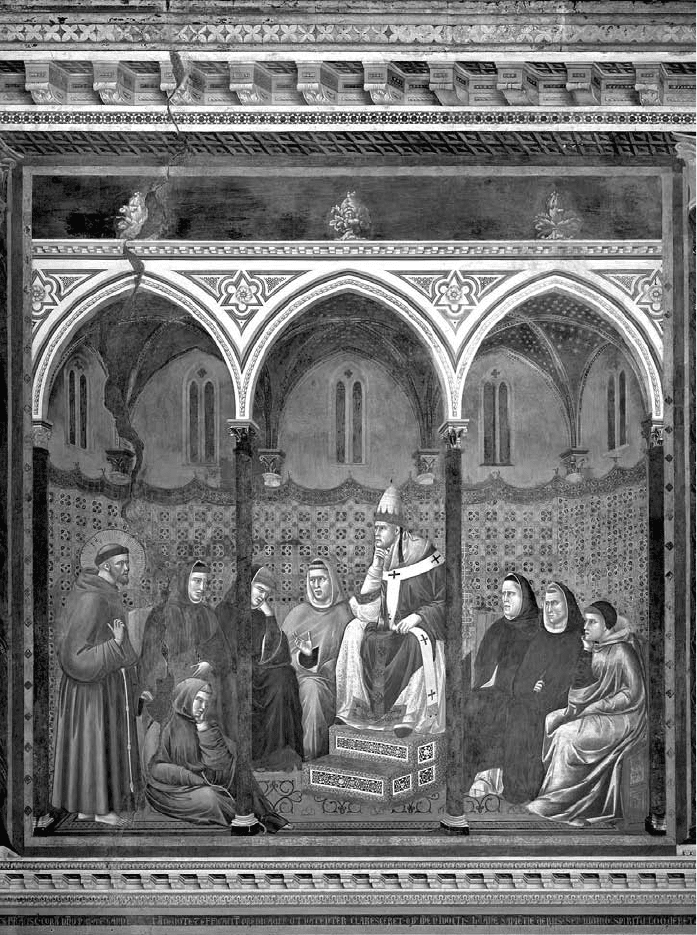

Giotto, the most prominent painter of the Middle Ages, commemorated the life of

Saint Francis in a series of wall frescoes in the church in Assisi, Italy. His use of natural

poses and visual perspective stunned his contemporaries and infl uenced all painting

after him. (Giraudon/The Bridgeman Art Library)

Painting

548

as secular remembrances of themselves, instead of only commissioning re-

ligious works. It was more important to the late Gothic painter to portray

real life than to evoke devotion.

Technically, painting leaped far ahead in the 15th century. Perspective

came fully into its own. Giotto’s use of perspective had been correct but

shallow; late Gothic painters created halls that receded and roads that wan-

dered to a true vanishing point. Flanders was the center of a new realistic

style of art, and artists like Jan van Eyck were leading innovators. Figures

were turned asymmetrically, and they leaned, slept, stooped, crossed their

arms or legs, looked bored or angry, or gazed at some unseen object. Row-

ers strained at oars, and Jesus on the cross slumped like a real dead body.

Plants and fl owers were not generic or symbolic; they were recognizable

European plants.

In popular art, the fi gure of Death, as a skeleton or a Grim Reaper, be-

came popular. Death was often dancing, pulling unwilling people into his

dance with other skeletons and corpses. In the Dance of Death pictures,

some people were rotting; ugliness was acceptable because death and life

could be ugly. Nudity was more acceptable in art, perhaps because so many

dying people had been seen or buried naked and the sight of the human

body was more commonplace. Sometimes religious art depicted the res-

urrection of the dead, with the rising dead as nudes. Artists began to sign

their works, from stained glass panels to frescos to portraits.

The Mechanics of Painting

Medieval paintings were not typically done on stretched canvas, as later

became standard. Wall paintings were the standard decoration not only

in churches, but also in many castle interiors. In Italy in the late Middle

Ages, wall paintings were often frescoes: tints painted directly onto wet

plaster to bond with the drying wall itself. Paintings were also created on

wood panels. These could be hung on a wall, or they could be altarpieces

that stood at the front of a church. Wood, not canvas, was the usual plat-

form for paint.

Paintings were also book illustrations. If medieval artistic artifacts were

counted as items, the paintings in books would far outnumber wall paint-

ings and altarpieces. By far the greatest number of artists in the Middle

Ages were worked in monasteries and cities, patiently creating detailed pic-

tures of daily life to illustrate a book of hours or a psalter. Much of what we

know about the period comes from observing the many scenes these artists

painted: building, spinning, farming, cooking, caring for children, joust-

ing, and scenes with animals of all kinds. Medieval book painters recorded

daily life in such detail that we can trace the development of some tools and

clothing styles, and we can see when eyeglasses fi rst came into use.

Painting

549

Painters used different materials for walls or for books. Paint was a chem-

ical bond between the tints and the material, and some kinds of paint and

painting techniques worked only on parchment or only on plaster. Half the

art of painting was knowing the secrets of mixing and using paint, while the

other half was, of course, drawing images that were realistic and beautiful.

Paintbrushes were made from animal hair, usually a squirrel’s. The hair

was bound on the end of a stick, much the same as today’s brushes. When

a painter worked, he did not usually use a fl at palette like a modern painter.

Paints were often mixed in oyster shells or wooden dishes. Archeologists

have discovered oyster shells with very old paint pigments still visible. Art-

ists worked on upright easels if they were painting a book page or a wood

panel. Many illustrations show artists working this way.

Paint is a binding agent mixed with pigments. To modern readers, who

think of paint as made by chemical companies, the natural ingredients used

by medieval painters can be startling or humorous. Toward the end of the

Middle Ages, painters and apothecaries had developed some artifi cial tints,

sometimes with fairly complicated chemical processes. Some binding agents

were more suitable for books or for walls, and some pigments worked only

for one or the other. Some paints could not be used next to others, since

they would create a chemical reaction that changed the color. A large part

of a painter’s education was in managing the chemicals and knowing which

ones to use and how.

Paint for books began with egg whites turned into glair, a liquid that

mixes well with pigments and pours and brushes well. Egg whites do not

mix well with anything until they have been beaten or strained. The fi n-

est method required the artist to hand whip the egg whites with a wooden

whisk until they were very stiff and then allow them to turn back into

liquid, which was called glair. When pigments were mixed into glair they

sometimes formed bubbles, and the best way to stop this was to add a bit

of earwax to the mix.

The other binding agent for book painting was gum arabic, the sap of an

acacia tree. Other tree gums also were used. When the gummy substance

was soaked in water, it provided a solution that would carry paint well.

When parchment scraps were soaked and then boiled, they dissolved into

the water and formed a jelly called size. Size was a good binding agent for

some blue pigments. Other odd ingredients for book paints included spin-

ach juice, apple vinegar, sugar, and stale beer.

The binding agent for wall or wooden panel painting was usually egg

yolk. This was the main paint used in Italy, and it was called tempera paint.

Egg yolk dried quickly and was glossy and long lasting. Its yellow color did

not alter the paint’s color much. Oil as a medium for tints came into use

only in the late Middle Ages. Especially in northern regions like Germany,

paint for murals was based on linseed oil.