Johnston R.A. All Things Medieval: An Encyclopedia of the Medieval World

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Prisons

590

Prisons

City prisons were a new development after the 12th century. They housed

debtors, prostitutes, and thieves. At fi rst, they were not intended as pun-

ishment in themselves; they housed those who were awaiting sentences or

debtors who could be freed if their debts were paid. Before that, crimes had

been handled at the most local level; the landowner locked up a suspect and

had a trial quickly, if at all. By the 15th century, prison time itself was used

as civil punishment.

Punitive sentences began as a means to limit the suffering of poor debt-

ors who could never buy their release because they would never be able

to pay their debts. Around 1300, cities like Venice began to translate the

amount of debt into time spent in prison. Since many of these debts were

really fi nes imposed by the city, the city could make a formula for what

length of time in prison was equal to a fi ne.

Into the 14th and 15th centuries, citizens could receive sentences of

varying lengths for failing to pay fi nes, breaking curfew, gambling, failing

to defend a ship against pirates, bigamy, assault, or breaking the city regu-

lations of a craft. While some sentences were as short as three days, some

were as long as fi ve years. The average medieval prison stay could have

been around two years. Prisons could become overcrowded and release

those who had been in the longest. Offi cials also released prisoners on some

church holidays.

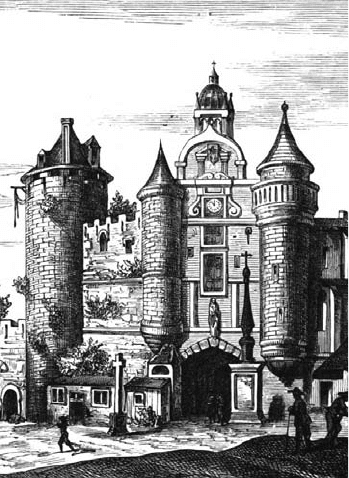

As cities grew, they had defensive structures they no longer needed. Some

cities used old forts and towers as prisons, while others had outgrown their

original gates and had massive gatehouses within the new city walls. The

city of Paris kept prisoners in the Châtelet, while the city of London used

some of its wall gatehouses, including the later-famous Newgate Prison.

Women were housed in convents at fi rst, in some places, but the nuns

complained because many of the inmates were prostitutes and their former

customers came to the convents. Cities began to build women’s prisons as

separate facilities. Because women inmates were vulnerable to abuse, their

quarters were made increasingly secure.

Supervisors, from city offi cials to priests to committees, and including

the doge of Venice, visited prisons regularly to make sure prisoners were

cared for. Friars often served the inmates, taking care of them as a service

and holding prayers and Masses with them. Prisons began to distinguish

wards for separating inmates not only according to wealth and rank, but

also for violence and disease. Most prisons also developed a lockdown ward

for the insane. Inmates could be subjected to corporal punishment within

the prison—as a penalty for fi ghting, for example. They could be fl ogged or

even dismembered; some were executed, if they were violent enough. Most

prisoners served their time without incident.

Prisons

591

Prisoners usually had to pay fees for their upkeep, as well as other fees

and taxes. This payment was part of working toward release. Poor prison-

ers were cared for at only a basic level; wealthier prisoners could pay extra

for more amenities. Since the poorest prisoners could not afford to pay the

fees to remain in prison, they ended up staying there indefi nitely because

the mounting fees were recorded as debt.

Daily life in a medieval prison was above all boring; there was no work,

and there were no activities beyond prayers and the charitable distribution

of food. Inmates talked, gambled, and fought. They could have visitors,

and, in fact, visitors were expected to come frequently and help pay their

fees or give them food.

See also: Cities, Monasteries.

Further Reading

Geltner, G. The Medieval Prison: A Social History. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Uni-

versity Press, 2008.

Pugh, Ralph B. Imprisonment in Medieval England. Cambridge: Cambridge Uni-

versity Press, 1968.

The old Chatelet fortress became a

prison as medieval Paris outgrew its

early walls and defenses. Its design for

keeping attackers out proved successful

at keeping criminals in. (Paul Lacroix,

Moeurs, Usage et Costumes au Moyen

Age et a l’Epoque de la Renaissance,

1878)

R

Records

595

Records

Most of what we know about medieval Europe is based on some kind of

written record created at the time; the only other record is the archeologi-

cal one. Examining standing castles, excavating buried walls and houses,

digging in trash pits, and looking at collected artifacts in museums, histori-

ans can see some of the setting and props of medieval life. The archeologi-

cal record is the bedrock of understanding the medieval material culture.

But many things have been lost; medieval people and those who came after

them were tremendous recyclers who melted, cut, shredded, and burned

much of the past. Few clothes have come into the present; over time, they

were passed down to younger and poorer folks, cut into children’s smocks,

made into rags, stuffed into pillows, and sold for paper pulp. Whatever

could rot or rust often has done so, and only the stone, bronze, and gold

remains.

The written record created at the time does not always tell us what we

want to know. The Middle Ages was not a time when the past was valued,

except in terms of the wisdom of the ancients, such as Pliny or Aristotle.

Italian sculptors carved Roman pillars into saints, and Roman plumbing

was melted down to make new pipes or lead pilgrims’ badges. There was

little effort to preserve the details of their own time until the 14th and 15th

centuries, when some people used the new paper technology to start keep-

ing journals. When they did create records, they were writing about what

interested them, from the price of hay that season to the miracles worked

at the local saints’ shrine. We have to look at what interested them to piece

together what interests us.

Moreover, the loss of records has been immense. There were ordinary

problems like fl oods and fi res. The Great Fire of London, in 1666, burned

more than half the city, and many medieval guild records were lost. In cer-

tain periods, people recycled their records as materials for rags or wrappings,

to make a list or to mend another book. In other periods, they destroyed

them on purpose. When the English closed all the monasteries in the 16th

century, many books were lost or destroyed. During the French Revolu-

tion, peasants deliberately destroyed anything that had belonged to royalty.

The 15th-century household account books of Duke Philip the Good of

Burgundy were used to make cannon cartridges in 1793; only one volume

escaped destruction. Historians would be able to glean many facts about

the economy of the time if more volumes had survived into the present.

Written records are both written texts and visual depictions. There are

stylized, decorative texts and images, and there are detailed, accurate ones.

There are personal accounts and public writings, propaganda and legends.

By carefully examining these records, historians can fi nd clues about daily

life that the record makers did not intentionally explain.

Records

596

Visual Images

The only records of medieval clothing are in paintings and sculpture.

By comparing different artists’ book illustrations and tomb effi gies of the

same period, we can generalize and understand what people wore. What

we cannot know easily is whether the picture is showing something typical

or unusual. Book illustrators often showed scenes that were not connected

to the text, which was usually religious. There was no narrative to explain

the picture. Are these people dressed for a party or wearing their everyday

garb? Was this detail, such as bells hung from their belts, a fad that year, or

did they put bells on for Christmas games?

Most of what we know about tools comes from pictures. Medieval il-

lustrators drew many scenes of building, so we have hundreds of images of

scaffolding, cranes, hammers, and saws. Some crafts were depicted more

often than others; we have few images of tanners or butchers compared

to masons and plowmen. Still, the great variety of imagination that paint-

ers could exercise in creating psalters and books of hours means that many

activities are shown at least once: sharpening pens, pruning vines, cutting

leather for shoes, polishing armor, and many more.

In the 14th and 15th centuries, many more people commissioned me-

morial brass plaques. Instead of having only a few expensive tomb effi gies

of queens, for these centuries we have fi gures of thousands of men and

women etched on brass in awkward but detailed formal poses. The names

permit us to trace the histories and dates of the people, so we can see with

more accuracy what people wore and considered important in different de-

cades and social classes.

Government Records

Literacy came to the Franks with Christianity, and although most nobles

could not read until after the time of Charlemagne, they employed clerks to

keep records. Frankish estates kept surveys now called polyptychs because

the parchment was folded many times. They kept lists of their tenants and

how much rent they paid each year. These simple books are among the fi rst

records of Europe’s economy.

The Franks and Anglo-Saxons kept tax rolls listing all tax-paying adults

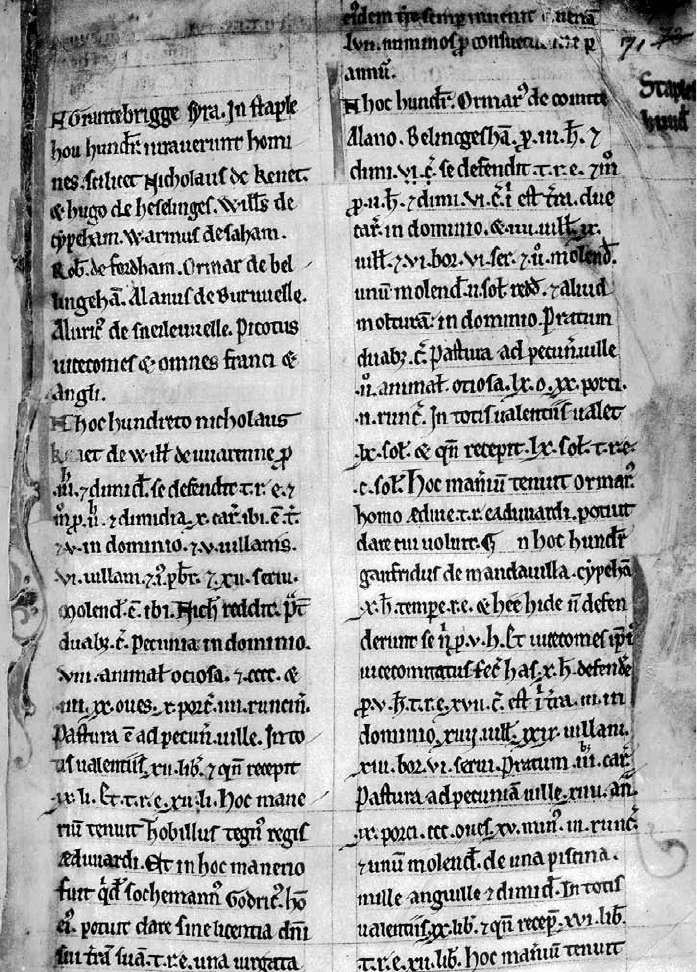

and how much they were assessed for. In 1085, William I of England, bet-

ter known as William the Conqueror, authorized a detailed taxation cen-

sus of his new realm. In the 20 years since his conquest in 1066, he had

rewarded his followers with many manors and castles. The survey set out

to learn how much land was held by the church and how many people,

plows, and animals were on each manor. The book was known at the

time simply as “the King’s great book,” but by the 12th century it was

known as the Domesday Book, a nicknamed based on the Bible’s account

The Domesday Book was a tax roll compiled for King William I. Its rigorous detail

was unmatched in its time and remained the highest standard for centuries after.

Most economic histories use the Domesday Book’s database, although it leaves

unanswered many questions that modern scholars ask. (The British Library/

StockphotoPro)

Records

598

of a great book used on Judgment Day, in which every man’s deeds are

recorded.

The Domesday Book preserved a snapshot of the economy in one year.

Each county’s entry began with a list of the men who held manors in it,

beginning with the king himself and including bishops and abbots. Each

lord’s land was then subdivided into hundreds and half-hundreds. Within

each parcel, every manor was listed, with the names of the men who farmed

it and how many villeins (workers obligated to stay on the estate) and slaves.

The census stated its assessment for taxes and military duty and told how

many plows worked the manor. For some counties, the book lists livestock:

horses, cattle, sheep, and pigs.

There are offi cial records of legal codes produced under the kings. While

we cannot tell how well these laws were enforced, we can get a sense of what

prompted the law and what the circumstances were. A particularly detailed

legal document is England’s Magna Carta, the document that rebellious

barons forced King John to sign in 1215. The Magna Carta listed all the

ways the king’s power had to be limited, and from this we can see what was

considered normal. Also in 1215, the Pope issued the results of the Fourth

Lateran Councils; the fi ve medieval all-church councils produced detailed

rulings on vexing problems of church government. These documents are

among the offi cial, intentionally created records of the Middle Ages.

Town and county governments kept coroners’ records, and these are

among the richest records of medieval life, although they recorded only

deaths. In medieval England, inquests asked why the death occurred and

took statements from witnesses. A typical entry is short, but it tells the

name and age of the deceased and the way the death happened. This tells us

what that person was doing at the moment of death and what others were

doing. A child falls into a river on the way to school; a baby is mauled by

a pig wandered in from the street; a child is burned to death when a ser-

vant’s careless candle catches the house on fi re. Historians can study where

accidental deaths occurred and get a good sense of where people were on

a typical medieval day.

Manorial and town courts kept records of infractions reported and fi nes

imposed. In many cases, the records are so laconic that we learn little of

the lives they speak of. An ale brewer is fi ned, but the court does not say

why, because fi ning ale brewers was too common for interest. Peasants are

fi ned for taking wood, hay, and animals from the lord’s land, but we know

nothing more about their lives. Peasants paid fees at events like a marriage

or a death, but we do not know how harsh the fees were economically or

whether they were always exacted.

However, we learn about normal life by reading about what disrupted

it. There are records of lawsuits and contract disputes. A modern reader

of an apprenticeship contract fi nds it all so foreign that it seems hard to

Records

599

understand what could go wrong. Reading a body of court records of ap-

prenticeship disputes, the assumptions and offenses of medieval life become

clearer. A medieval father objected more when his son was not properly

taught skills and less if he was not treated kindly, unless the unkindness was

dangerous. Masters complained most often of apprentices who ran away.

Guilds were reluctant to break contracts without a period of time for either

party to amend his ways.

Dowry, betrothal, and marriage contracts appear frequently in the court

rolls, as families argued over whether the terms had been fulfi lled. The me-

dieval practices of family law, such as wardship of orphans, would be virtu-

ally unknown apart from court records of disputes. We know from court

records that orphans’ wardships were sold, sometimes repeatedly. We know

that both men and women tried to hold each other accountable for prom-

ises of marriage, even marriages made orally without a written contract.

The evidence of witnesses tells us where people were and what they con-

sidered normal in daily life; the incidents they testify about took place in

homes, taverns, and workplaces. We get a sense of how friendships were

formed in the testimonies about how long each witness had known the par-

ties to the lawsuit.

In English village court records, we can observe their method of com-

munity policing. If anyone was attacked, he or she had to “raise the hue

and cry.” In calling for help loudly, that person placed everyone in earshot

under the obligation to drop his or her work and run to help. When a vil-

lage did not respond to the call, the victim could bring a complaint to the

magistrate and have not only the attacker but also the village fi ned.

Personal Wills and Notarial Accounts

Wills, especially in the late Middle Ages, often had detailed inventories of

a person’s possessions, including clothing, books, dishes, and tools. Much

of our knowledge of people’s lives comes from close scholarly reading of

many old wills. By studying a person’s profession, and his or her compara-

tive wealth, scholars can determine how well a profession was fl ourishing in

a time or how much social respect it commanded in society.

Notaries kept records of wills and other contracts in large towns. In the

progressive Italian towns, notary service was a well-developed profession.

Italy’s towns could have had some ongoing notarial services since Roman

times, but they at least revived the Roman practice of public notaries when

the University of Bologna began to teach Roman law in the 11th cen-

tury. Italian notarial records go back to about 1150. Charlemagne copied

Roman practice by instituting the role of a notary among the Franks, but

these notaries were mostly private secretaries for a long time. As private sec-

retaries to princes and courts, the notaries recorded many decrees and court