Luscombe D., Riley-Smith J. The New Cambridge Medieval History, Vol. 4: c. 1024-c. 1198, Part 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

I

Ji—^ 1 1

If V

L/Y

u

( ^, />__ 0 50 100 150 200

250 km

f

|№\

{

SCOTLAN&y

T\ I I—H N 1 ? I

Jt\ //U 1 /

,v

i֊ ' K 0 50 100

1 50

miles

Vf^. ,

^O^WGIArfORGAM

v_>Abingdon

·

Jfel3

^^i^Sx*

, Bristol

•

D

«

vizes

Wi^o%^

n

^P^Jer

J<cM

) C^"'^ ^

^fflTmTj

V /՝

Tonbridge* ,CPNT» i"n!

e

U

,Y

/wH * / \ ֊-/֊

\ ClarendorTf

r,

A

., , „

K

m

L№ii»r /\<«SV*

CI f

J\

) ) 11

Winchester Arundel Saltwoodyff

yth

e^^^cP

ƒ" V 1

\-^j֊֊^

\P

(^»Cambrai

y if

,

r^--.

Barfleur MUHUJIC^

w , JV f\ 1

Cherbourg-T

·

LeTilleulJ» Roumare«Warenne

^ J j b

§5==

^onUs^l^^Mortag^)^

VW/ ^ ^

^ BRITTANY. JL» Ferté-Bernard.

\* j sent'TN '^f-N V /

^,

„ \

Rennesf

J

MAINE ^fiontrrilraH

5ens

f

\ X ^ VTv^ ^ \

^t^<TT^^^Wn^5

A. \ V O

«ion

( ^ J«S^

<^

N

^>^֊---.^^"V,

ou

^!a!-^.<<L»Bourges

y

a;

J S XX

_

V

Bellay Loud<rn

V

K

^-» .

՝0»«*V^

f ?

I

I \

POITOU "Mirebeauy Châteauroux

05

) S

I

I

Lands Inherited by Henry II

////^A/Y///)v

/

'

AA///XA^\ V '

/^^~~\

I I Lands acquired by Henry ll's marriage to

^ÏK/jt^^sy

//A/^V./y?/V/x^///yO/*

\ *°B V^"^

Eleanor of Aquitaine ՝\La Rochelle

[ LA

MARCHE

\ ^ J ^» I

I

Lands claimed

by

right of suzerainty

or

conquest

<

^^

L

"^aintesm^^v ^jr^^^^

^ \ ՝\

—

<

^

N

^—\

I I

Capetian royal domain

/xv'

Angoulême /yyWyy»77^o\

] 7 i /՝^^՝ \

„

,

fV^L^Vy^CXyi'I

IT A I N F

•<^

r

S*

,

'/'3l

^

AlAURIENNE

—— Borders of France and the empire

^/J^/^//^3^^/^^/y^v^^^///Vyl

Le

COUNTY.

«...

Borders of Angevin lands

/o

Ty3w^—^w^^^^'^՝"^^%^^rv^3^^'

\ (

Borders of other fiefs ^^Bordeaux^^ Dmdogney' ^^^^^J^^A

M '~՝^

CONY/^^J*^^^,

՝X^

Ê

%^°J

՝՝y

Ç

V^^^o^^^

^^^^^^y

==

^^^^

d

X

j^

M

?^!^^^^ROVBNC^/^

I

r i x

^r^

5

^,

I

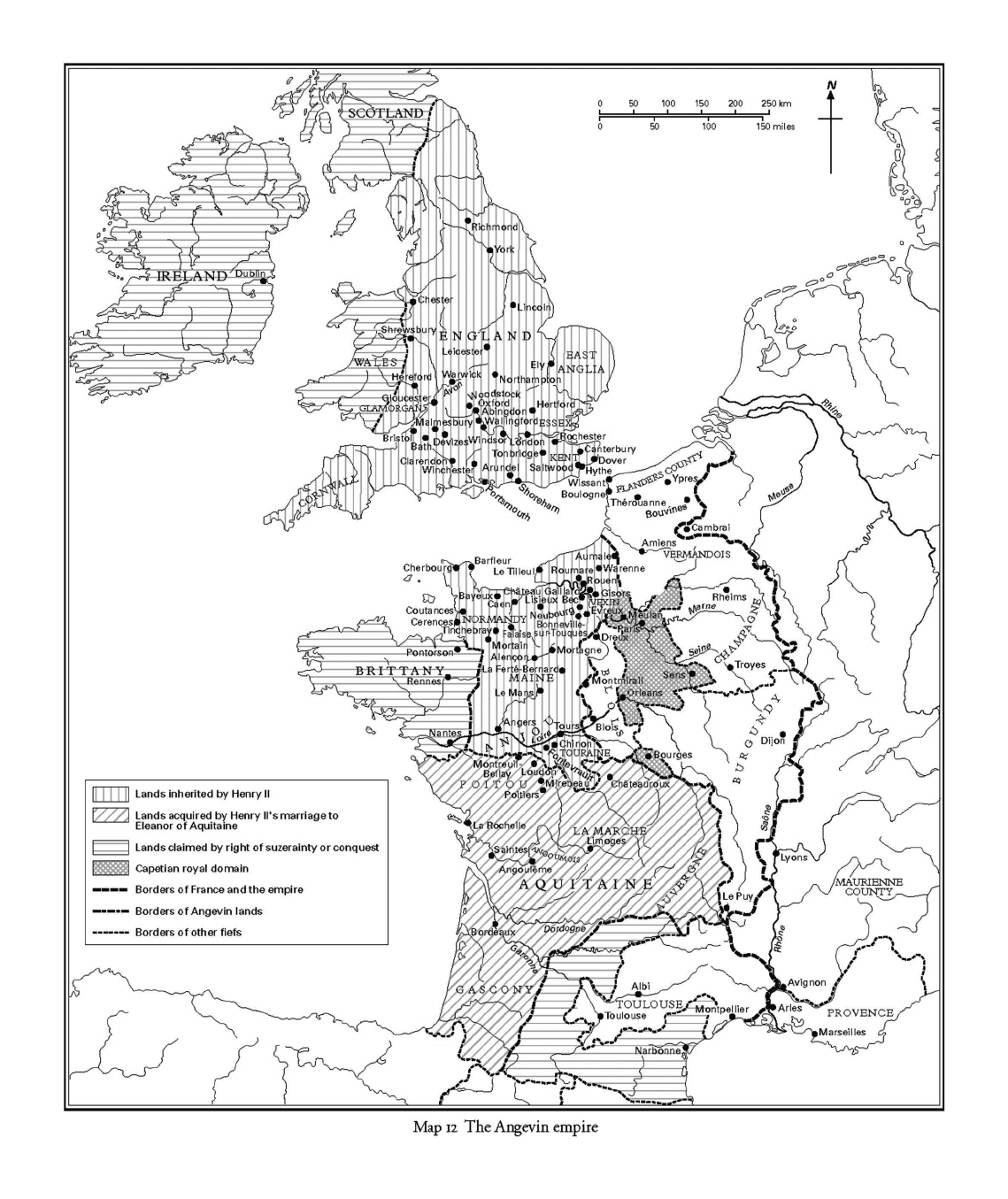

Map 12 The

Angevin empire

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

552 thomas k. keefe

I’s plan for his grandson and namesake to succeed him, if necessary, following

aregency of Matilda and Geoffrey, was that no English castles or towns were

assigned to the couple for a base of operations against the chance of a fight for

the succession, which, of course, happened. Matilda and Geoffrey had to rely

on great magnates like Robert, especially in Britain.

All the reasons for Earl Robert choosing to remain behind in Normandy

after Stephen’s departure in November, 1137, then, formally to renounce his

allegiance to the king in May 1138, may never be known. Surely, he recognized

the child Henry, his nephew, as the only legitimate Anglo-Norman ruler in

spite of Stephen’s anointing, but Henry was too young to rule, his mother’s

gender posed a serious barrier to her rule, even to a prolonged regency, while

her husband’s descent from the Normans’ age-old Angevin enemies made his

overlordship out of the question. If Robert thought of the future, he worked

in the present. His family ties with Matilda and Geoffrey always would be a

cause for suspicion. Stephen’s Flemish mercenary captain, William of Ypres,

had devised at least one attempt on the earl’s life already. And the earl’s in-

fluence at the royal court had been steadily undermined in countless ways by

the Beaumont group, most notably the king’s confidant, Count Waleran of

Meulan. The earl in the end acted while he was still free to do so and in some

measure by serving his sister he served himself.

In June 1138 Count Geoffrey invaded Normandy. Now with Bayeux and

Caen being held for Matilda by her brother, and Stephen facing rebellion

and a Scottish invasion in England, the expectation must have been to take

Normandy finally. It was not to be. Waleran of Meulan and William of Ypres,

coming from England, blunted the Angevin advance with the support of Count

Ralph of Vermandois and French troops. Earl Robert was forced to find security

behind the strong walls of Caen, where he remained inactive for months,

while Count Geoffrey found sanctuary in Argentan after his near disaster at

Bonneville-sur-Touques. Angevin partisans in England fared little better.

In the winter of 1138 King David of Scotland, Matilda’s uncle, had in-

vaded northern England reaching the River Tyne before being chased back

into Scotland by a determined Stephen, who clearly saw the Scottish advance

as a serious challenge to his kingship and ability to protect the north. In April

David crossed the border once again with a large army, espousing the right

of his niece to the English throne, while taking advantage of the unsettled

situation to press age-old Scottish territorial ambitions in Northumbria and

beyond. Stephen could not meet this second challenge in person. By chance

or design, rebellion had broken out along the Welsh march, in the south-west,

and in Kent where Earl Robert’s supporters and castles were situated. Bristol,

Hereford and Shrewsbury, to name the principal places, were all in rebel hands.

So too was the pivotal fortress of Dover which was held for Earl Robert by his

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

England and the Angevin dominions, 1137–1204 553

castellan, Walchelin Maminot. Stephen concentrated his forces on the march

and Bristol. Queen Matilda, his wife, was sent against Dover supported by

ships from her county of Boulogne. The northern barons, under the guidance

of Archbishop Thurstan of York, had to fend for themselves. Angevin tactics,

if there was an overall strategy, seemed aimed at spreading the royal forces in

England as thinly as possible with the bonus of preventing significant reinforce-

ments from reaching Normandy, where Count Geoffrey’s invasion through the

centre of the duchy was in progress, and Reginald of Dunstanville, another

of Matilda’s half-brothers, Baldwin of Redvers, and Stephen of Mandeville,

aGloucester ally, were reeking havoc in the Cotentin. Earl Robert himself

curiously remained at Caen.

The strategy failed. Count Waleran of Meulan and others were dispatched,

as we have seen, to Normandy with substantial effect. In England, Stephen

first made an attempt on Bristol, but found the stronghold too formidable

and dangerously protected from siege by a broad arc of outlying castles in the

earl’s hands. The king then concentrated on taking Hereford, an effort which

lasted five weeks. A second try at Bristol proved equally fruitless. After a string

of successes with smaller castles in the region, Stephen invested Shrewsbury,

taking the town and castle in little over a week. It was late August. About

this time, Dover capitulated to Queen Matilda, and within days the Scots

were resoundingly defeated by the northern barons near Northallerton at the

battle of the Standard. For the moment serious fighting in England ceased. By

November the Angevin progress in Normandy, too, had been stalemated.

If the Angevin revanche of 1138 failed to produce any immediate territorial

gains, it did shake the foundations of the Anglo-Norman world, bringing to

the fore the weaknesses of Stephen’s kingship and the many dangers of the

current political situation. In spite of the year’s string of royal victories, with

towns and castles taken or retaken and invasions repelled, the Angevin group’s

leaders remained at large and unreachable. For all the expense, for all the hard

campaigning, nothing had been decided. Continued conflict was certain, and

Stephen most likely had exhausted the treasure left the monarchy by Henry I.

Normandy was beyond Stephen’s or anyone’s control, as its barons fought each

other as vigourly as they fought the Angevins. In England and Wales, Stephen’s

failure to invest methodically or reduce the greatest of the rebel strongholds –

Bristol and Wallingford stand out – meant that civil war could continue seem-

ingly without end; it did.

On 30 September 1139, Earl Robert and Matilda landed at Portsmouth

with a body of knights and made their way safely to Arundel Castle. Stephen,

having had notice of their coming, had ordered watches day and night over

the harbours along the southern shores. He was no doubt furious that Robert

had managed his entry undetected, and more furious still when he arrived at

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

554 thomas k. keefe

Arundel with his army only to learn that the earl had slipped away in the night

with a bodyguard of twelve knights in an attempt to cross the south of England

and reach his men at Bristol. All the by-roads had been blocked by guards at

the first notice of the landing and it is even rumoured that Henry of Blois,

bishop of Winchester and papal legate, had actually caught up with the earl

but let him go in peace. The story may be fanciful, though the bishop had

reason enough to spite his brother, since Stephen had recently connived with

the Beaumonts to deny Henry election to the archbishopric of Canterbury

and had arrested three curial bishops, stripping them of their castles, again at

the suggestion of the Beaumonts. Court politics and rivalries played no small

part in allowing the Angevins to gain a necessary foothold in England. The

empress Matilda (the title she continued to use after the death of her first

husband, preferring it to the lesser title of countess), the legitimate heir to

the English throne according to the professed oaths of the barons taken on

several occasions during Henry I’s lifetime, was now in England to claim her

inheritance. Equally importantly, Earl Robert, the natural military leader of the

Anglo-Normans among the Angevin group, had reached Bristol unmolested,

bringing over such powerful magnates as Miles of Gloucester and Brian fitz

Count to the Angevin side.

Arundel Castle held two women of royal rank, the empress and her protec-

tress, the queen dowager, Adeliza, widow of Henry I. Adeliza’s second husband,

William of Albini pincerna and loyal to the king, was also in the castle, but de-

cisions rested with Adeliza for Arundel was hers through dower. To begin what

would be a lengthy siege had drawbacks for Stephen, who was encamped out-

side, beyond allowing Earl Robert the freedom to rally his forces uncontested.

Public opinion, never to be discounted, might swing dramatically away from

Stephen if the king led a brutal assault on the castle holding these two high-

born women. After all, only a few months had passed since he had shocked

the clergy and many courtiers outside the Beaumont affinity with the arrest

of the bishops. On the other hand, if Stephen tried and did not capture the

castle, his reputation might not easily recover from the embarrassment of being

defeated by a female-commanded garrison. Besides the military threat lay with

Robert, not with Matilda. What would Stephen do if he took her? Send her

back to Normandy, imprison her? Never known as a deep thinker, the king’s

problem was resolved for him by his brother, Henry bishop of Winchester,

who advised that it would be wiser to let Matilda go unharmed to the earl;

they could be contained and attacked all the more easily in one part of the

country. And so the empress Matilda was escorted by the Beaumont, Waleran

of Meulan, and Bishop Henry himself all the way to Bristol. Reflecting on this

unusual sequence of events, the contemporary historian Orderic Vitalis vented

his exasperation over this chivalric act: ‘the king showed himself very guileless

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

England and the Angevin dominions, 1137–1204 555

or very foolish, and thoughtful men must deplore his lack of regard for his own

safety and the security of the kingdom’.

2

The match for the English throne

hardly was over, yet in the last months of 1139 an end game had indeed begun.

But neither the king, nor the Angevins, were strong enough to gain a mean-

ingful advantage over the other as they played siege and run. Many must have

felt, as William of Malmesbury did, the insecurity and anxiety of not knowing

what might happen next or who would protect them. In William’s word’s,

‘there were many castles all over England, each defending its own district or,

to be more truthful, plundering it’.

3

As the end game progressed, an offer of

mediation came from an unlikely source, King Stephen’s own brother Henry,

bishop of Winchester, the papal legate. Somehow Henry arranged a meeting

at Bath in May 1140 between Robert, earl of Gloucester, as the empress’s repre-

sentative, and Matilda, Stephen’s queen and a practised negotiator. Theobald

of Bec, archbishop of Canterbury, attended along with Bishop Henry, making

the church the primary go-between in seeking a resolution to the spreading

civil war. Details of the discussions are lost to us, although they must have

been promising enough for Bishop Henry to set out in September for France

where he consulted with his eldest brother, Count Theobald of Blois, the head

of the family, and King Louis VII of France whose obvious political interest

in the outcome of the struggle for Normandy and England was newly bound

up with familial concern: his sister had just married Stephen’s son and heir,

Eustace. Later in November Bishop Henry returned to England with a sug-

gested solution, again unknown, acceptable to the empress and her party, but

not to Stephen. The proposed solution very probably was some variation on

what would come to pass years later: Stephen was to remain king for his life-

time, while Matilda’s and Geoffrey’s son, Henry, would inherit the kingdom his

grandfather had intended for him. Clearly, Stephen meant to concede nothing

without a fight. He got his wish, although he might have thought twice about

tempting fortune. As one contemporary warned: ‘Let no one . . . depend on

the continuation of Fortune’s favours, nor presume on her stability, nor think

that he can long maintain his seat erect on her revolving wheel.’

4

On Sunday

2 February 1141, King Stephen was taken prisoner by the Angevins at Lincoln.

The battle of Lincoln was one of those rare occasions in Anglo-Norman

experience, like Tinchebray, where opposing forces risked everything in a single

encounter. That the battle took place at all was chance, the result of a quarrel

between the king and two brothers, Ranulf, earl of Chester, and William of

Roumare, who were upset by the king’s mismanagement of patronage. They

sought, as did so many others during the civil war, their own self-interest, in

2

Ibid., vi,p.534.

3

William of Malmesbury, Historia novella, ch. 483.

4

Henry of Huntingdon, Historia Anglorum,pp.266–7.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

556 thomas k. keefe

this instance mastery of a block of territory stretching from Cheshire beyond

Lincoln to the eastern coast. Shortly before Christmas 1140 the two brothers

tricked the royal garrison at Lincoln and seized its castle, with which went the

town and the surrounding region. Winter did not deter Stephen from reacting

quickly to an appeal from the bishop of Lincoln and townspeople for aid.

On the night of 6 January, he entered the town so unexpectedly that several

of Ranulf’s men were taken captive returning to the castle from an evening’s

revelry. Earl Ranulf somehow managed to escape, leaving behind his wife,

Robert of Gloucester’s daughter, and brother. The earl of Chester, who had

never shown sympathy for the empress’s cause before, now sent messengers

to Robert of Gloucester, his father-in-law, pledging support if Robert would

help rescue those, including his daughter, who were in danger of captivity.

The earl of Gloucester, putting aside resentment towards his son-in-law for

having remained neutral up to this point, seized the moment and gathered

together a large army of his own vassals, Welsh allies and those disinherited by

Stephen. He moved on Lincoln from Gloucester, taking an indirect route, and

on the way joined up with Ranulf coming from Chester with another body

of Welsh troops in his command. The Angevin army arrived at the outskirts

of Lincoln early on the morning of 2 February. Surprised, many of those with

the king argued against risking battle, suggesting instead that he withdraw to

some safer quarter to marshal a larger army, while a small detachment defended

themselves in Lincoln as best they could. Stephen would listen to none of this

talk of withdrawal. His advisers were ridiculed by younger knights as being

‘battle-shy boys’.

5

What went through Stephen’s mind in deciding on battle

only can be guessed at. Count Geoffrey of Anjou had eluded him in Normandy;

Earl Robert to this point had avoided any direct confrontation. The kingdom

was suffering more and more from this civil war and flight now would invite

comparison with his father, who, after having run away from Antioch during

the First Crusade, later died in ignominy. On this day the Blois’s family past

coloured Stephen’s judgement. He stayed; he fought; he was captured. What

the king had not foreseen was the treachery of his own greater supporters, many

of whom, including six earls, abandoned the battlefield at the outset of combat.

Taken first to a meeting with the empress at Gloucester, Stephen found himself

within a fortnight imprisoned in the earl of Gloucester’s castle at Bristol.

Fortune’s wheel continued its wild spin through the remainder of 1141.

The taking of the king did not end the game after all. In a process which

rewarded speed, the empress’s party moved too slowly. By summer, Matilda’s

own mismanagement of the political situation had cost her the support of the

Londoners and Bishop Henry of Winchester, who, again in his comfortable role

5

John of Hexham in Simeon of Durham, Opera omnia, ii,p.307.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

England and the Angevin dominions, 1137–1204 557

of power-broker, had smoothed the way for her coronation at Westminster.

On 24 June she was forced to flee London in a general uprising, not yet a

queen. Another Matilda, Stephen’s queen, entered the city the same day in

triumph backed by a loyalist army. For their revenge, the Angevins sought out

the bishop of Winchester. The bishop, having changed sides once more, now

was in agreement with his sister-in-law that his brother should be restored

to the throne by any means possible. As the empress’s troops besieged the

episcopal palace at Winchester, Queen Matilda came down in relief with her

considerable army and a host of Londoners. With much of the city burnt

and supplies dwindling, the Angevins decided upon withdrawal before being

completely encircled. Withdrawalturned to rout. The empressmade it to safety,

but Robert of Gloucester was taken prisoner defending her escape. With the

earl in captivity at Rochester Castle, with members of their party scattered far

and wide, the Angevins agreed to the only workable solution: an exchange of

king for earl. The exchange took place in the first week of November. What had

been done at the battle of Lincoln seemed undone by the rout of Winchester,

but not quite.

News of King Stephen’s capture at Lincoln had sent a seismic wave through

Normandy. What once had seemed insurmountable, now came about. Count

Geoffrey of Anjou broke the Normans’ defence. And his relentless, if slow,

conquest of Normandy led to the ultimate success of the Angevin party. In

March when Geoffrey called upon the barons to surrender their castles, a

group met at Mortagne and made another offer to Count Theobald of Blois

to become their duke. Not only did the count of Blois refuse the offer, he

countered with an offer of his own to Geoffrey. He would give up any claim to

the Anglo-Norman inheritance in return for Stephen’s release, the restoration

of his personal estates and the small favour of Tours. The court of Anjou

cleverly met this bid with silence. Nor was help forthcoming at this time from

Stephen’s ally, King Louis VII of France. Unfazed by the prospect of a union

of England and Normandy with Anjou, the French king took an army south

during the spring of 1141 to press his wife’s claims to Toulouse. In despair,

Norman towns, among them Lisieux and Falaise, began their submissions. By

autumn, even Waleran, count of Meulan, had joined the Angevin court. With

this, Count Geoffrey was in control of central Normandy.

In the summer of 1142, while Geoffrey contemplated how to consolidate and

extend his gains, Robert of Gloucester arrived in Normandy and urged him to

come to England with an army large enough to confront Stephen’s revitalized

forces. Stephen, no longer trusting the great magnates, many of them earls of

his own creation, after the experience at Lincoln, had surrounded himself with

anew court and household troop made up of men dependent upon him and

not likely to measure every move against their own territorial self-interest. Since

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

558 thomas k. keefe

the Angevin party in England saw no hope of overcoming this leaner, more

dogged, royal force on their own, they feared for their cause, and, in truth, for

their lands. Now more than ever Geoffrey’s help was needed in securing the

English inheritance of his wife and their children. The count’s perspective was

much different. He had never been to England. He knew neither its people,

nor its geography. Why risk the future on a gamble across the Channel when

Normandy finally lay open to conquest? Besides, who would guard Anjou in his

absence or for that matter Angevin-held Normandy? In a turn about, Geoffrey

enlisted Robert in the winning of western Normandy. Perhaps this was in the

count’s mind all along. The earl’s presence in the count’s vanguard, his prestige

within Anglo-Norman society, his military acumen, all would contribute to

further successes. The main target was King’s Stephen’s county of Mortain.

First Tinchebray fell, then Mortain itself, followed by Le Teilleul, Pontorson

and Cerences. The lesson for the Norman barons still holding out in the west

was clear: submit – no one could possibly save them; even King Stephen was

powerless to retain his Norman lands – submit. And the submissions came.

With the fall of Cherbourg in the autumn of 1143, virtually all of Normandy

west and south of the Seine was in Geoffrey’s hands.

Meanwhile the situation in England had deteriorated in Earl Robert’s ab-

sence, forcing his return in November 1142, half-way through the campaign

for western Normandy. Let down by the men left to protect her, and besieged

in Oxford Castle, the empress was in imminent danger of being taken prisoner

by Stephen. Once again fate intervened. Matilda miraculously escaped the

trap on her own a few days before Christmas, walking five to six miles in the

night through snow and ice to Abingdon, then riding with her small escort to

the safety of Wallingford Castle, where Earl Robert found her. Although not

known at the time, this proved to be the last in a series of remarkable adven-

tures and near misses for the empress, which left at least one contemporary,

the author of the Gesta Stephani, astonished:

Idonot know whether it was to heighten the greatness of her fame in years to come,

or by God’sjudgement...,butneverhaveIreadofanotherwomansoluckily rescued

from so many mortal foes and from the threat of dangers so great; the truth being that

she went from the castle of Arundel uninjured through the midst of her enemies and

escaped without a scratch from the midst of the Londoners . . . , stole away alone in

wondrous fashion, from the rout of Winchester, when almost all her men were cut off;

and then, when she left besieged Oxford, came away, . . . safe and sound.

6

From Wallingford, Robert took the empress to the greater security of Devizes

Castle, where she stayed until finally leaving England in 1148.Travelling with

them was her eldest son Henry, a boy of nine.

6

Gesta Stephani,p.144.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

England and the Angevin dominions, 1137–1204 559

That Henry, not Count Geoffrey, had been brought back to England with

the earl of Gloucester was significant. Here was the future, the true heir to

the Anglo-Norman dominion of his grandfather, Henry I, and perhaps as a

male, the individual and symbol to rekindle the hopes of the Angevin party

in England. Henry remained at Bristol with his uncle’s household until being

recalled to Normandy shortly before the fall of Rouen in April 1144 and his

father’s investiture as duke. As Count Geoffrey took over the governance of the

whole of the duchy, and set about restoring order, it must have been understood

by the Normans that for their cooperation, Henry, who was being raised as

an Anglo-Norman, would be made their duke as soon as he came of age. This

may well have been King Louis VII’s understanding too when he recognized

Geoffrey’s title (in exchange for the Norman Vexim) and helped the duke put

down the last of the Norman resistance.

In and after 1144,events outside the Anglo-Norman world counted, per-

haps more than at any other time, towards Angevin success. One barrier to

the Angevin cause in England had always been papal recognition of Stephen’s

proper, and thus sacred, anointing. This recognition, given by Pope Innocent II

in 1136, was reaffirmed in 1139 when the same pope set aside Empress Matilda’s

appeal for Stephen’s deposition as an oath-breaker and a usurper without the cu-

ria voting or otherwise reaching a final decision. The election of Pope Celestine

II in 11in 1143, following Innocent’s death, was a boon for the Angevins. As a

cardinal, Celestine had heard the 1139 debate and had developed a sympathy

for the empress’s case, which later evolved into a friendship with the empress

herself. Although Celestine’s pontificate lasted only a few months (September

1143 to March 1144), it was time enough to influence the next English succes-

sion. As it happened, Archbishop Theobald of Canterbury was in Rome on

other business during early 1144 and was told by Celestine in no uncertain

words that no innovation should be allowed regarding the throne, since its

transfer, justly disputed, had never been resolved. Here was an opening worth

exploiting. Many within and without the church from the mid-1140s onwards

increasingly saw young Henry Plantagenet, heir to Normandy, as the logical

and rightful heir to England as well.

In 1147,Henry revealed himself at the age of fourteen to be an intrepid war-

rior in the making by mounting an expedition of like adventurers on England

without anyone else’s knowledge, his parents included. However, the bond

formed about this time with the powerful Cistercians, and their leader Bernard

of Clairvaux, by Geoffrey and Matilda was far more important for the future.

The amalgamation of the Cistercians with Norman Savigny conpregation and

its daughter houses in England no doubt raised the level of Bernard’s interest

in the progress of Anglo-Norman affairs. A personal involvement is suggested

by the presence of Bernard’s brother, Nivard, in Normandy during the final

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

560 thomas k. keefe

negotiations with the Savignacs and then in south Wales at the inauguration

of Margam Abbey, founded by Robert of Gloucester. Nivard conferred with

Matilda on his journey. Meanwhile, Geoffrey met Bernard himself in Paris.

Also in Paris were Archbishop Theobald of Canterbury and Pope Eugenius

III, Bernard’s prot

´

eg

´

e. This coming together of the greatest Cistercian abbot

and the primate of England, occasioned by King Louis VII’s departure on

the Second Crusade, gave Geoffrey the opportunity to cultivate all three, to

turn them to the Angevin viewpoint regarding the English succession, or at

least to try to do so. Certainly, Matilda and Robert, for their part, must have

said something to Nivard of Angevin intentions, something of the benefits of

mutual cooperation.

The bond with the Cistercians helped the Angevin party survive the twin

shocks of Robert of Gloucester’s death in October 1147 and the empress’s depar-

ture from England shortly thereafter in January 1148. Any advantage Stephen

might have won from these events was lost in his clash with Bernard and the

pope over the archiepiscopal election to the see of York and the attendance

of English bishops at the council of Rheims. Stephen’s brother the bishop of

Winchester was of little use, since he had been suspended from office and called

to Rome for absolution for his role in the war. Following Rheims, the bishop

of Th

´

erouanne went to England at Duke Geoffrey’s urging and denounced

Stephen as an usurper. The stage was being set. In Rome Eugenius III gath-

ered the cardinals to hear once again the case of the English succession. Then

fate intervened. News of the terrible defeat of the crusading armies reached

Rome; overwhelmed with emotion, the papal curia quit its deliberations. The

case went unresolved. Nevertheless, the real casualty of Stephen’s embroilment

with the church was his son Eustace’s chance of being crowned co-king. As long

as his annointing was prevented, as long as the Angevin party maintained a

foothold in England, hope prevailed. In October 1148 Empress Matilda, Duke

Geoffrey and their three sons gathered in Rouen to map out the next move.

7

The plan, as it evolved, called for Henry to go to England, where he would

be knighted by his uncle the king of Scotland, take the homage of Angevin

supporters and afterwards return to Normandy for his formal investiture as

duke, all accomplished by March 1150. This simplified many matters. Henry

at the age of sixteen entered his inheritance with the boundless energy and

excitement of youth, revitalizing the Angevin party. Matilda, long used to living

independently without her husband, stayed in the Norman environment of

Rouen as an adviser to her eldest son, assisting him in the governance of the

duchy. Geoffrey, true to his bargain in giving the Normans a duke whom they

could call their own, refocused his attentions on keeping peace in Anjou, always

7

Chibnall (1991), p. 153.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008