Meszaros G. xUnit Test Patterns Refactoring Test Code

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

xviii

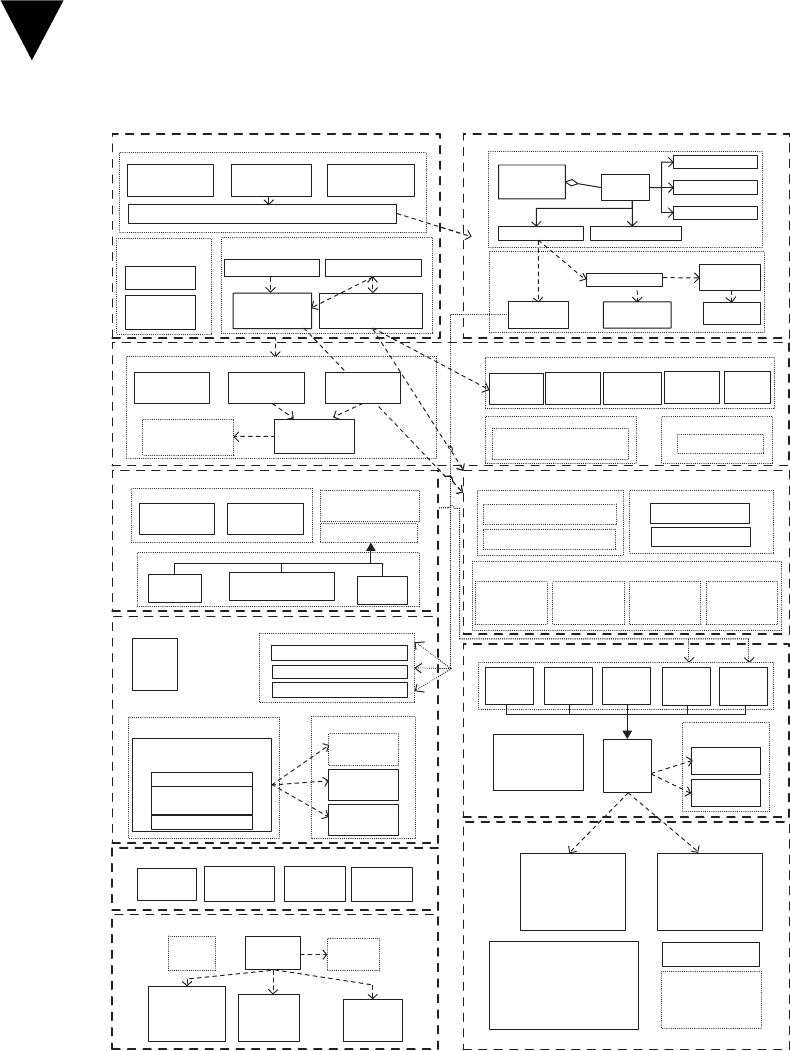

The Patterns

Test Double

Construction

Hard -Coded

Test Double

Confiugrable

Test Double

Dummy

Object

Fake

Object

Test

Stub

Test

Spy

Mock

Object

Test Double Patterns

Test

Double

Test-Specific

Subclass

Subclassed Test

Double

Fixture Setup Patterns

Literal

Value

Derived

Value

Generated

Value

Dummy

Object

Value Patterns

Design- for-Testability Patterns

Dependency

Injection

Setter Injection

Parameter Injection

Constructor Injection

Humble Object

Humble Container Adapter

Humble Transaction Controller

Humble Executable

Humble Dialog

Test Hook

Dependency

Lookup

Object Factory

Service Locator

Test-Specific

Subclass

Substituted Singleton

xUnit Basics Patterns

Test Selection

Test Suite Object

Test Execution

Test

Runner

Test Discovery

Test

Automation

Framework

Test Definition

Testcase

Class

Assertion

Method

Assertion

Message

Four Phase

Te st

Test Enumeration

Test Case Object

Test Method

Database Patterns

Stored

Procedure

Test

Transaction

Rollback

Teardown

Ta bl e

Truncation

Teardown

Lazy Teardown

Database

Sandbox

Delta

Assertion

Fake

Database

Delta

Assertion

Behavior

Verification

Guard

Assertion

Custom Assertion

Verification Method

Result Verification Patterns

State

Verification

Assertion Method

Back Door

Verification

VerificationStrategy

Assertion Method Styles

Scripted

Test

Data-Driven

Test

Standard Fixture

Minimal Fixture

Layer Test

Back Door

Manipulation

Shared Fixture

Immutable Fixture

Test Fixture Strategy

Test Automation Strategy Patterns

Recorded

Test

Fresh Fixture

Test Automation Strategy

SUT Interaction

Strategy

Persistent

Transient

Test Automation Framework

Fresh Fixture Setup

Shared Fixture Construction

Lazy

Setup

SuiteFixture

Setup

Setup

Decorator

Chained

Tests

Prebuilt

Fixture

Result Verification

Delta Assertion

Test Utility Method

Finder Method

Shared Fixture Access

Inline

Setup

Delegated

Setup

Implicit

Setup

Creation

Method

Fixture TearDown Patterns

Shared Fixture

Persistent Fresh Fixture

Applicability

Inline Teardown

Implicit Teardown

Code Organization

Strategy

Automated

Teardown

Garbage-

Collected

Teardown

Transaction

Rollback

Teardown

Ta bl e

Truncation

Teardown

Test Organization Patterns

Testcase

Superclass

Test Helper

Object Mother

Testcase

Class

Utility Method Location

Named

Test

Suite

Testcase Class Structure

Testcase Class per Class

Testcase Class per Fixture

Testcase Class per Feature

Test Code Reuse

Test Utility Method

Finder Method

Custom Assertion

Verification Method

Creation Method

Parameterized Test

Test Helper

Object Mother

Test Double

Construction

Hard -Coded

Test Double

Confiugrable

Test Double

Dummy

Object

Fake

Object

Test

Stub

Test

Spy

Mock

Object

Test Double Patterns

Test

Double

Test-Specific

Subclass

Subclassed Test

Double

Fixture Setup Patterns

Literal

Value

Derived

Value

Generated

Value

Dummy

Object

Value Patterns

Design- for-Testability Patterns

Dependency

Injection

Setter Injection

Parameter Injection

Constructor Injection

Humble Object

Humble Container Adapter

Humble Transaction Controller

Humble Executable

Humble Dialog

Test Hook

Dependency

Lookup

Object Factory

Service Locator

Test-Specific

Subclass

Substituted Singleton

xUnit Basics Patterns

Test Selection

Test Suite Object

Test Execution

Test

Runner

Test Discovery

Test

Automation

Framework

Test Definition

Testcase

Class

Assertion

Method

Assertion

Message

Four Phase

Te st

Test Enumeration

Test Case Object

Test Method

Database Patterns

Stored

Procedure

Test

Transaction

Rollback

Teardown

Ta bl e

Truncation

Teardown

Lazy Teardown

Database

Sandbox

Delta

Assertion

Fake

Database

Delta

Assertion

Behavior

Verification

Guard

Assertion

Custom Assertion

Verification Method

Result Verification Patterns

State

Verification

Assertion Method

Back Door

Verification

VerificationStrategy

Assertion Method Styles

Scripted

Test

Data-Driven

Test

Standard Fixture

Minimal Fixture

Layer Test

Back Door

Manipulation

Shared Fixture

Immutable Fixture

Test Fixture Strategy

Test Automation Strategy Patterns

Recorded

Test

Fresh Fixture

Test Automation Strategy

SUT Interaction

Strategy

Persistent

Transient

Test Automation Framework

Fresh Fixture Setup

Shared Fixture Construction

Lazy

Setup

SuiteFixture

Setup

Setup

Decorator

Chained

Tests

Prebuilt

Fixture

Result Verification

Delta Assertion

Test Utility Method

Finder Method

Shared Fixture Access

Inline

Setup

Delegated

Setup

Implicit

Setup

Creation

Method

Fixture TearDown Patterns

Shared Fixture

Persistent Fresh Fixture

Applicability

Inline Teardown

Implicit Teardown

Code Organization

Strategy

Automated

Teardown

Garbage-

Collected

Teardown

Transaction

Rollback

Teardown

Ta bl e

Truncation

Teardown

Test Organization Patterns

Testcase

Superclass

Test Helper

Object Mother

Testcase

Class

Utility Method Location

Named

Test

Suite

Testcase Class Structure

Testcase Class per Class

Testcase Class per Fixture

Testcase Class per Feature

Test Code Reuse

Test Utility Method

Finder Method

Custom Assertion

Verification Method

Creation Method

Parameterized Test

Test Helper

Object Mother

Visual Summary of the Pattern Language

Foreword

If you go to junit.org, you’ll see a quote from me: “Never in the fi eld of software

development have so many owed so much to so few lines of code.” JUnit has

been criticized as a minor thing, something any reasonable programmer could

produce in a weekend. This is true, but utterly misses the point. The reason JUnit

is important, and deserves the Churchillian knock-off, is that the presence of this

tiny tool has been essential to a fundamental shift for many programmers: Testing

has moved to a front and central part of programming. People have advocated it

before, but JUnit made it happen more than anything else.

It’s more than just JUnit, of course. Ports of JUnit have been written for lots

of programming languages. This loose family of tools, often referred to as xUnit

tools, has spread far beyond its java roots. (And of course the roots weren’t really

in Java—Kent Beck wrote this code for Smalltalk years before.)

xUnit tools, and more importantly their philosophy, offer up huge opportu-

nities to programming teams—the opportunity to write powerful regression test

suites that enable teams to make drastic changes to a code-base with far less risk;

the opportunity to re-think the design process with Test Driven Development.

But with these opportunities come new problems and new techniques. Like

any tool, the xUnit family can be used well or badly. Thoughtful people have

fi gured out various ways to use xUnit, to organize the tests and data effectively.

Like the early days of objects, much of the knowledge to really use the tools

is hidden in the heads of its skilled users. Without this hidden knowledge you

really can’t reap the full benefi ts.

It was nearly twenty years ago when people in the object-oriented commu-

nity realized this problem for objects and began to formulate an answer. The

answer was to describe their hidden knowledge in the form of patterns. Gerard

Meszaros was one of the pioneers in doing this. When I fi rst started exploring

patterns, Gerard was one of the leaders that I learned from. Like many in the

patterns world, Gerard also was an early adopter of eXtreme Programming,

and thus worked with xUnit tools from the earliest days. So it’s entirely logical

that he should have taken on the task of capturing that expert knowledge in the

form of patterns.

I’ve been excited by this project since I fi rst heard about it. (I had to launch

a commando raid to steal this book from Bob Martin because I wanted it to

xix

xx

grace my series instead.) Like any good patterns book it provides knowledge

to new people in the fi eld, and just as important, provides the vocabulary and

foundations for experienced practitioners to pass their knowledge on to their

colleagues. For many people, the famous Gang of Four book Design Patterns

unlocked the hidden gems of object-oriented design. This book does the same

for xUnit.

Martin Fowler

Series Editor

Chief Scientist, ThoughtWorks

Foreword

Preface

The Value of Self-Testing Code

In Chapter 4 of Refactoring [Ref], Martin Fowler writes:

If you look at how most programmers spend their time, you’ll fi nd that

writing code is actually a small fraction. Some time is spent fi guring out

what ought to be going on, some time is spent designing, but most time

is spent debugging. I’m sure every reader can remember long hours of

debugging, often long into the night. Every programmer can tell a story

of a bug that took a whole day (or more) to fi nd. Fixing the bug is usually

pretty quick, but fi nding it is a nightmare. And then when you do fi x a bug,

there’s always a chance that anther one will appear and that you might not

even notice it until much later. Then you spend ages fi nding that bug.

Some software is very diffi cult to test manually. In these cases, we are often

forced into writing test programs.

I recall a project I was working on in 1996. My task was to build an event

framework that would let client software register for an event and be notifi ed

when some other software raised that event (the Observer [GOF] pattern). I

could not think of a way to test this framework without writing some sample

client software. I had about 20 different scenarios I needed to test, so I coded up

each scenario with the requisite number of observers, events, and event raisers.

At fi rst, I logged what was occurring in the console and scanned it manually.

This scanning became very tedious very quickly.

Being quite lazy, I naturally looked for an easier way to perform this test-

ing. For each test I populated a

Dictionary indexed by the expected event and

the expected receiver of it with the name of the receiver as the value. When a

particular receiver was notifi ed of the event, it looked in the Dictionary for the

entry indexed by itself and the event it had just received. If this entry existed,

the receiver removed the entry. If it didn’t, the receiver added the entry with an

error message saying it was an unexpected event notifi cation.

After running all the tests, the test program merely looked in the Dictionary

and printed out its contents if it was not empty. As a result, running all of my

tests had a nearly zero cost. The tests either passed quietly or spewed a list of test

failures. I had unwittingly discovered the concept of a Mock Object (page 544)

and a Test Automation Framework (page 298) out of necessity!

xxi

My First XP Project

In late 1999, I attended the OOPSLA conference, where I picked up a copy of

Kent Beck’s new book, eXtreme Programming Explained [XPE]. I was used to

doing iterative and incremental development and already believed in the value

of automated unit testing, although I had not tried to apply it universally. I had

a lot of respect for Kent, whom I had known since the fi rst PLoP

1

conference in

1994. For all these reasons, I decided that it was worth trying to apply eXtreme

Programming on a ClearStream Consulting project. Shortly after OOPSLA,

I was fortunate to come across a suitable project for trying out this develop-

ment approach—namely, an add-on application that interacted with an existing

database but had no user interface. The client was open to developing software

in a different way.

We started doing eXtreme Programming “by the book” using pretty much all

of the practices it recommended, including pair programming, collective owner-

ship, and test-driven development. Of course, we encountered a few challenges

in fi guring out how to test some aspects of the behavior of the application, but

we still managed to write tests for most of the code. Then, as the project pro-

gressed, I started to notice a disturbing trend: It was taking longer and longer to

implement seemingly similar tasks.

I explained the problem to the developers and asked them to record on each

task card how much time had been spent writing new tests, modifying existing

tests, and writing the production code. Very quickly, a trend emerged. While

the time spent writing new tests and writing the production code seemed to be

staying more or less constant, the amount of time spent modifying existing tests

was increasing and the developers’ estimates were going up as a result. When

a developer asked me to pair on a task and we spent 90% of the time modify-

ing existing tests to accommodate a relatively minor change, I knew we had to

change something, and soon!

When we analyzed the kinds of compile errors and test failures we were

experiencing as we introduced the new functionality, we discovered that many

of the tests were affected by changes to methods of the system under test (SUT).

This came as no surprise, of course. What was surprising was that most of the

impact was felt during the fi xture setup part of the test and that the changes

were not affecting the core logic of the tests.

This revelation was an important discovery because it showed us that we

had the knowledge about how to create the objects of the SUT scattered across

most of the tests. In other words, the tests knew too much about nonessential

1

The Pattern Languages of Programs conference.

Preface

xxii

parts of the behavior of the SUT. I say “nonessential” because most of the af-

fected tests did not care about how the objects in the fi xture were created; they

were interested in ensuring that those objects were in the correct state. Upon

further examination, we found that many of the tests were creating identical or

nearly identical objects in their test fi xtures.

The obvious solution to this problem was to factor out this logic into a small

set of Test Utility Methods (page 599). There were several variations:

• When we had a bunch of tests that needed identical objects, we simply

created a method that returned that kind of object ready to use. We

now call these Creation Methods (page 415).

• Some tests needed to specify different values for some attribute of the

object. In these cases, we passed that attribute as a parameter to the

Parameterized Creation Method (see Creation Method).

• Some tests wanted to create a malformed object to ensure that the SUT

would reject it. Writing a separate Parameterized Creation Method for

each attribute cluttered the signature of our Test Helper (page 643), so

we created a valid object and then replaced the value of the One Bad

Attribute (see Derived Value on page 718).

We had discovered what would become

2

our fi rst test automation patterns.

Later, when tests started failing because the database did not like the fact

that we were trying to insert another object with the same key that had a unique

constraint, we added code to generate the unique key programmatically. We

called this variant an Anonymous Creation Method (see Creation Method) to

indicate the presence of this added behavior.

Identifying the problem that we now call a Fragile Test (page 239) was an im-

portant event on this project, and the subsequent defi nition of its solution pat-

terns saved this project from possible failure. Without this discovery we would,

at best, have abandoned the automated unit tests that we had already built. At

worst, the tests would have reduced our productivity so much that we would

have been unable to deliver on our commitments to the client. As it turned out,

we were able to deliver what we had promised and with very good quality. Yes,

the testers

3

still found bugs in our code because we were defi nitely missing some

tests. Introducing the changes needed to fi x those bugs, once we had fi gured

2

Technically, they are not truly patterns until they have been discovered by three inde-

pendent project teams.

3

The testing function is sometimes referred to as “Quality Assurance.” This usage is,

strictly speaking, incorrect.

Preface

xxiii

out what the missing tests needed to look like, was a relatively straightforward

process, however.

We were hooked. Automated unit testing and test-driven development really

did work, and we have been using them consistently ever since.

As we applied the practices and patterns on subsequent projects, we have

run into new problems and challenges. In each case, we have “peeled the on-

ion” to fi nd the root cause and come up with ways to address it. As these tech-

niques have matured, we have added them to our repertoire of techniques for

automated unit testing.

We fi rst described some of these patterns in a paper presented at XP2001.

In discussions with other participants at that and subsequent conferences, we

discovered that many of our peers were using the same or similar techniques.

That elevated our methods from “practice” to “pattern” (a recurring solution

to a recurring problem in a context). The fi rst paper on test smells [RTC] was

presented at the same conference, building on the concept of code smells fi rst

described in [Ref].

My Motivation

I am a great believer in the value of automated unit testing. I practiced software

development without it for the better part of two decades, and I know that my

professional life is much better with it than without it. I believe that the xUnit

framework and the automated tests it enables are among the truly great ad-

vances in software development. I fi nd it very frustrating when I see companies

trying to adopt automated unit testing but being unsuccessful because of a lack

of key information and skills.

As a software development consultant with ClearStream Consulting, I see a

lot of projects. Sometimes I am called in early on a project to help clients make

sure they “do things right.” More often than not, however, I am called in when

things are already off the rails. As a result, I see a lot of “worst practices” that

result in test smells. If I am lucky and I am called early enough, I can help the

client recover from the mistakes. If not, the client will likely muddle through

less than satisfi ed with how TDD and automated unit testing worked—and the

word goes out that automated unit testing is a waste of time.

In hindsight, most of these mistakes and best practices are easily avoid-

able given the right knowledge at the right time. But how do you obtain that

knowledge without making the mistakes for yourself? At the risk of sounding

self-serving, hiring someone who has the knowledge is the most time-effi cient

way of learning any new practice or technology. According to Gerry Weinberg’s

Preface

xxiv

“Law of Raspberry Jam” [SoC],

4

taking a course or reading a book is a much

less effective (though less expensive) alternative. I hope that by writing down a

lot of these mistakes and suggesting ways to avoid them, I can save you a lot of

grief on your project, whether it is fully agile or just more agile than it has been

in the past—the “Law of Raspberry Jam” not withstanding.

Who This Book Is For

I have written this book primarily for software developers (programmers,

designers, and architects) who want to write better tests and for the managers

and coaches who need to understand what the developers are doing and why

the developers need to be cut enough slack so they can learn to do it even bet-

ter! The focus here is on developer tests and customer tests that are automated

using xUnit. In addition, some of the higher-level patterns apply to tests that are

automated using technologies other than xUnit. Rick Mugridge and Ward Cun-

ningham have written an excellent book on Fit [FitB], and they advocate many of

the same practices.

Developers will likely want to read the book from cover to cover, but they

should focus on skimming the reference chapters rather than trying to read them

word for word. The emphasis should be on getting an overall idea of which pat-

terns exist and how they work. Developers can then return to a particular pat-

tern when the need for it arises. The fi rst few elements (up to and include the

“When to Use It” section) of each pattern should provide this overview.

Managers and coaches might prefer to focus on reading Part I, The Nar-

ratives, and perhaps Part II, The Test Smells. They might also need to read

Chapter 18, Test Strategy Patterns, as these are decisions they need to under-

stand and provide support to the developers as they work their way through

these patterns. At a minimum, managers should read Chapter 3, Goals of Test

Automation.

About the Cover Photo

Every book in the Martin Fowler Signature Series features a picture of a bridge

on the cover. One of the thoughts I had when Martin Fowler asked if he could

“steal me for his series” was “Which bridge should I put on the cover?” I

thought about the ability of testing to avoid catastrophic failures of software

4

The Law of Raspberry Jam: “The wider you spread it, the thinner it gets.”

Preface

xxv

and how that related to bridges. Several famous bridge failures immediately

came to mind, including “Galloping Gertie” (the Tacoma Narrows bridge) and

the Iron Workers Memorial Bridge in Vancouver (named for the iron workers

who died when a part of it collapsed during construction).

After further refl ection, it just did not seem right to claim that testing might

have prevented these failures, so I chose a bridge with a more personal con-

nection. The picture on the cover shows the New River Gorge bridge in West

Virginia. I fi rst passed over and subsequently paddled under this bridge on a

whitewater kayaking trip in the late 1980s. The style of the bridge is also rel-

evant to this book’s content: The complex arch structure underneath the bridge

is largely hidden from those who use it to get to the other side of the gorge. The

road deck is completely level and four lanes wide, resulting in a very smooth

passage. In fact, at night it is quite possible to remain completely oblivious to

the fact that one is thousands of feet above the valley fl oor. A good test automa-

tion infrastructure has the same effect: Writing tests is easy because most of the

complexity lies hidden beneath the road bed.

Colophon

This book’s manuscript was written using XML, which I published to HTML

for previewing on my Web site. I edited the XML using Eclipse and the XML

Buddy plug-in. The HTML was generated using a Ruby program that I fi rst

obtained from Martin Fowler and which I then evolved quite extensively as I

evolved my custom markup language. Code samples were written, compiled,

and executed in (mostly) Eclipse and were inserted into the HTML automati-

cally by XML tag handlers (one of the main reasons for using Ruby instead of

XSLT). This gave me the ability to “publish early, publish often” to the Web

site. I could also generate a single Word or PDF document for reviewers from

the source, although this required some manual steps.

Preface

xxvi

Acknowledgments

While this book is largely a solo writing effort, many people have contributed to it

in their own ways. Apologies in advance to anyone whom I may have missed.

People who know me well may wonder how I found enough time to write

a book like this. When I am not working, I am usually off doing various (some

would say “extreme”) outdoor sports, such as back-country (extreme) skiing,

whitewater (extreme) kayaking, and mountain (extreme) biking. Personally, I

do not agree with this application of the “extreme” adjective to my activities

any more than I agree with its use for highly iterative and incremental (extreme)

programming. Nevertheless, the question of where I found the time to write this

book is a valid one. I must give special thanks to my friend Heather Armitage,

with whom I engage in most of the above activities. She has driven many long

hours on the way to or from these adventures with me hunched over my laptop

computer in the passenger seat working on this book. Also, thanks go to Alf

Skrastins, who loves to drive all his friends to back-country skiing venues west of

Calgary in his Previa. Also, thanks to the operators of the various back-country

ski lodges who let me recharge my laptop from their generators so I could work

on the book while on vacation—Grania Devine at Selkirk Lodge, Tannis Dakin at

Sorcerer Lodge, and Dave Flear and Aaron Cooperman at Sol Mountain Touring.

Without their help, this book would have taken much longer to write!

As usual, I’d like to thank all my reviewers, both offi cial and unoffi cial. Rob-

ert C. (“Uncle Bob”) Martin reviewed an early draft. The offi cial reviewers of

the fi rst “offi cial” draft were Lisa Crispin and Rick Mugridge. Lisa Crispin, Jer-

emy Miller, Alistair Duguid, Michael Hedgpeth, and Andrew Stopford reviewed

the second draft.

Thanks to my “shepherds” from the various PLoP conferences who provided

feedback on drafts of these patterns—Michael Stahl, Danny Dig, and especially

Joe Yoder; they provided expert comments on my experiments with the pattern

form. I would also like to thank the members of the PLoP workshop group

on Pattern Languages at PLoP 2004 and especially Eugene Wallingford, Ralph

Johnson, and Joseph Bergin. Brian Foote and the SAG group at UIUC posted

several gigabytes of MP3’s of the review sessions in which they discussed the

early drafts of the book. Their comments caused me to rewrite from scratch at

least one of the narrative chapters.

Many people e-mailed me comments about the material posted on my Web

site at http://xunitpatterns.com or posted comments on the Yahoo! group; they

xxvii