Moyar Mark. A Question of Command: Counterinsurgency from the Civil War to Iraq

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

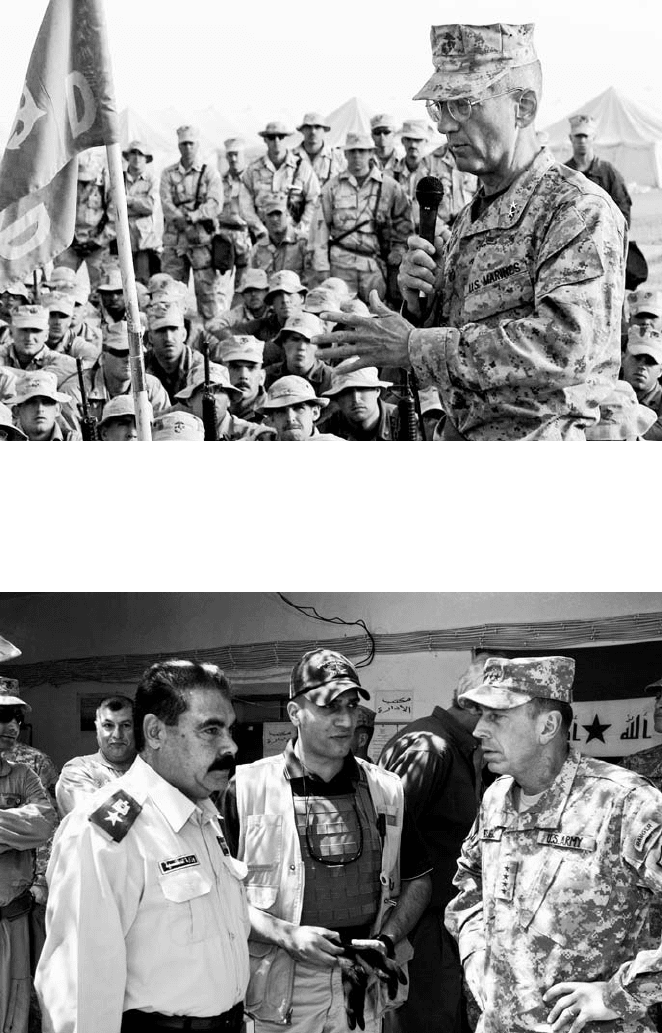

MAJOR GENERAL JAMES N. MATTIS

Mattis, who commanded with distinction in both Afghanistan and Iraq, embodied the

reliance of the U.S. Marine Corps on adaptive leadership, having once declared that

“doctrine is the refuge of the unimaginative.” (U.S. Department of Defense)

GENERAL DAVID PETRAEUS

While holding a series of key commands in Iraq and the United States, Petraeus (right)

sought to improve the exibility and creativity of Army leaders by challenging the U.S.

Army’s traditional personnel practices. (U.S. Department of Defense)

e Malayan Emergency 125

next morning feeling like an electric torch which has just been lled with new

batteries.”38 Templer’s magnetism and his attentiveness to the soldiers, police,

and civil servants made him a popular man in all of the government’s branches

and at all levels. A young British ocer described Templer as “dynamic, enthu-

siastic, energetic, and for someone in my position a hero, who was always open

to ideas from junior ocers like myself.”39 Templer’s élan was contagious, per-

meating the top levels of the British leadership and working its way through

them and down to the state and district ocials.40

No less energizing were Templer’s appearances before the public. During

trips to the villages, he went into shops and alleys to talk with ordinary citi-

zens, and at their conclusion he gathered the people together for a motivational

speech in which he told them of the critical tasks that lay ahead.41 At planta-

tions and mines he lectured managers on the necessity of improving working

conditions and told the laborers to work hard and resist Communist demands

for strikes, but without coming across as domineering. On hearing Templer,

one planter said, “Here was a man at least who knew what he wanted to do

and how to do it.” Templer’s “visit was greatly appreciated and everyone on the

estate had an opportunity of airing his views, asking questions and meeting

him face to face. No previous High Commissioner had taken the trouble to do

this.”42

In Kuala Lumpur, Templer chided the Europeans for attending parties,

playing golf, and going to the races instead of volunteering for activities in

support of the counterinsurgency. e Communists, he told them, were work-

ing hard to destroy the Europeans and the existing order, not wasting time on

the golf course. Templer published a list of volunteer opportunities, ranging

from health-care providers to the Home Guard, and large numbers of Euro-

peans signed on.43

Templer concluded that the security forces would benet from common

tactical doctrine, so he ordered the production of a doctrinal manual containing

drills and techniques that had proven successful in combating the insurgents

across Malaya. Entitled e Conduct of Anti-Terrorist Operations in Malaya,

the manual was sent to army and police units in mid-1952.44 e importance

of this manual has been exaggerated, and the exaggeration has, among other

things, contributed directly to the U.S. Army’s emphasis on counterinsurgency

doctrine in the early twenty-rst century and to the attention aorded the pub-

lication of the U.S. Army /Marine Corps Counterinsurgency Field Manual in

2006. Templer’s praise of the 1952 manual and the major improvements in the

126 e Malayan Emergency

British counterinsurgency eort aer the manual’s issuance misled analysts

into believing that the manual was a leading cause of the improvements. e

methods enumerated in e Conduct of Anti-Terrorist Operations in Malaya

had, in reality, been disseminated and employed in Malaya long before the

manual was printed. During the rst years of the conict, British veterans of

Burma and Palestine had used many of these methods because they had used

the same ones in those wars. In 1948 the British established a jungle warfare

school in Malaya at which the instructors taught tactics derived largely from

those employed in the war in Burma, and by 1949 the British were circulating

pamphlets and a short manual derived from the experiences in Burma, Pales-

tine, and the Boer War, as well as from discoveries made by innovative ocers

in Malaya.45

Operations in Malaya from 1948 to 1952 had engendered only modest re-

nements of the theories drawn from past conicts. e principles and basic

military methods employed by the British in this period were very similar

to those enumerated in prior treatises, such as the Small Wars Manual pub-

lished by the U.S. Marine Corps in 1940. e prescriptions in e Conduct of

Anti-Terrorist Operations in Malaya were useful to newly arrived ocers and

soldiers with no knowledge of counterinsurgency but did not provide easy

solutions to most counterinsurgency problems. ey did not give ocers sure-

re methods for accomplishing essential tasks like gaining the cooperation of

allied leaders, organizing self-defense forces, winning the support of the popu-

lation, motivating the troops, persisting in the face of diculty, or adjusting

methods in response to changing enemy tactics.46

e jungle warfare school emphasized to its students that the school could

teach them basic tactics and techniques but that it was up to them to gure

out whether, when, and how to use each one.47 e Conduct of Anti-Terrorist

Operations in Malaya itself acknowledged that successful military operations

demanded excellent leadership, not just comprehension of methods. “Opera-

tions in Malaya largely consist of small patrols,” it stated. “e success or fail-

ure of these operations therefore depends on the standard of junior leaders. . . .

e type of junior leader required is a mentally tough, self-reliant hunter, de-

termined to close with, and kill, the CT [Communist Terrorists].” e manual

also noted that commanders above the platoon level had as a principal duty

the monitoring, selection, and coaching of the platoon leaders. “e company

commander plays the major part in the selection and training of the junior

leader,” it explained. “By operating with each platoon in turn, he can give help

e Malayan Emergency 127

and advice to junior leaders, earmark future leaders and can generally do more

in a few days to improve junior leadership than a cadre [training group] could

do in three weeks.”48

Templer considered his mission to be the implementation of the Briggs

plan through better employment of methods already in place, rather than

through major changes to those methods. Although he promoted doctrine,

Templer was not doctrinaire but pragmatic and suspicious of abstractions, par-

ticularly theories that purported to apply everywhere. Rather than forcing his

commanders to adhere closely to the new counterinsurgency manual, Templer

granted them freedom to adapt general counterinsurgency principles to the

specic environments they faced and the specic forces they possessed, both

of which varied from one part of Malaya to another. So conscious was Templer

of the dangers of imposing doctrine and micromanaging that he made special

eorts to give key commanders maximum freedom of action. In the case of

the district ocers, the most critical of all the commanders, Templer removed

both vertical and horizontal fetters, freeing them from the dictates of higher

headquarters and other district ocials. He gave them his phone number and

told them to call if anyone interfered with their work so that he could put an

end to the interference. To unblock district interagency committees that had

been clogged by lack of consensus among members, Templer informed the

committee members that they would be red if they failed to reach agree-

ment. is threat eliminated most of the gridlock; rings eliminated the re-

mainder.49

Replacing poor leaders with good ones, unshackling leaders, and provid-

ing inspiration—that was the potent combination that enabled Templer to

succeed where others had failed. Within a few months of his arrival, the re-

sults could be seen across the spectrum of counterinsurgency activities. In the

eld of intelligence collection, the heightened drive and ingenuity of Special

Branch ocers yielded more agents among the Min Yuen. Improved training

inculcated intelligence tradecra into the Special Branch ocer corps more

eectively, but without the right types of ocers conducting and receiving the

instruction, the training regimens would have achieved little more than previ-

ous ones.50

More and better intelligence meant more fruitful operations against the

insurgents, but it did not guarantee success, for exploitation of the intelligence

oen required considerable skill on the part of the armed forces. Nor did it

eliminate the need for patrols of the jungle based on educated guesses rather

128 e Malayan Emergency

than rm intelligence, a type of operation that, as has been seen, demands

leaders with particular attributes. In 1954, by which time the Special Branch

had become highly productive, the average soldier still spent 1,000 hours on

patrol before making contact with the enemy.51 Fortunately for the British, im-

provements on the military side were as substantial as those on the intelligence

side. Under Templer, military commanders evidenced increases in exibility

and creativity as well as initiative and dedication. As one of Templer’s senior

eld commanders said, “Most ocers I met were singularly free from hide-

bound prejudice. ey rejoiced to use any conventional weapon in an uncon-

ventional way; and they were always ready to have a try with any unconven-

tional weapon too.”52

Because of the leadership upgrades in the civil service, police, and Home

Guard, the counterinsurgents turned the New Villages and other resettlement

areas from fertile insurgent breeding grounds into well-organized armed

camps where insurgents could tread only at considerable peril. e police, as-

sisted by civil ocials and Home Guardsmen, investigated and rounded up

thousands of members of the Min Yuen. With civil liberties still in suspense,

the police employed searches without warrants, detentions without trial, and

other police-state techniques, but they committed fewer abuses than before

because of Young’s overhaul of the police leadership. Policemen and civil ser-

vants were energetic and creative in restricting the movement and consump-

tion of food. ey established central kitchens and forbade citizens from pur-

chasing any rice other than rice that had been cooked at the kitchens, which

sharply reduced the amount of rice available to an individual and provided it

in a form that spoiled in a few hours, before it could reach famished guerrillas

in the jungle. Village shops were required to puncture cans at the time of sale

to necessitate prompt consumption. As an additional means of increasing gov-

ernmental control over the population, civil servants organized the election

of village councils and authorized them to impose taxes and carry out public

works projects. Templer’s eorts to initiate larger social welfare programs were

frustrated by a scarcity of funds, but the lack of such programs did little to in-

hibit the government’s securing of control over the villagers.53

In Templer’s rst year, the government’s armed forces not only halted the

ascent of their Communist adversaries but shoved them down a precipitous

decline. Whereas the government in 1951 had captured 927 weapons and lost

770, in 1952 it captured 1,170 and lost 487. e New Villages slowed the transfer

of food from the Min Yuen to the guerrillas, severely impeding insurgent mili-

e Malayan Emergency 129

tary operations. Since the jungle’s few edible plants could at best sustain thirty

guerrillas in one place for about two weeks, the guerrillas began to operate in

groups of only three to een people and spent most of their time looking for

food instead of conducting military and political activities. In October 1952

the Communist Party ordered the guerrillas to undertake more ambitious at-

tacks, believing that a shortage of attacks had undermined the guerrillas’ mo-

rale and aided the government, but the guerrillas could not operate in groups

of sucient size to carry out the order. Government security forces easily re-

pulsed their few feeble attempts to overrun the resettlement areas. In 1952 the

insurgents for the rst time failed to recruit as many people as they lost, begin-

ning a trend that continued for the rest of the war. When Templer rst arrived,

insurgent incidents had averaged over 500 per month, and civilian casualties

had averaged 100 per month. When he le, insurgent incidents were down to

fewer than 100 per month, and civilian casualties to fewer than 20 per month.

At the end of Templer’s tour, insurgent strength stood at less than half of what

it had been at the start.54 Templer had turned the war around decisively, and

for good.

Upon Templer’s decision to step down in the middle of 1954, London de-

cided to discontinue the concentration of military and civil powers in one

man, convinced that improvements in the situation had rendered it unneces-

sary. Templer’s civilian deputy, Sir Donald MacGillivray, assumed control of

the civil side, while Lieutenant General Sir Georey Bourne took command

of military operations. is division of powers substantially reduced the e-

cacy of the counterinsurgency eort because the absence of a strong military

leader at the top of the civil side led to regression. e civil service dried back

toward a business-as-usual attitude, and the district ocers and other civil

servants appointed under Templer were eventually rotated out and replaced

by men of lesser aptitude.55

In the years following Templer’s departure, the government was unable to

deal a mortal blow to the Communists, but it did continue to make progress.

By the end of 1956, the guerrillas had barely more than 2,000 men.56 Malaya

gained its independence on August 31, 1957, removing much of the Malayan

Communist Party’s appeal and drawing many Communist sympathizers to

the parties of the non-Communist le. Malaya’s rst prime minister, Tunku

Abdul Rahman, shared Templer’s view that good government deserved prece-

dence over self-government in a time of civil war, so he hired into his govern-

ment the British, Australian, and New Zealand ocers who until now had

130 e Malayan Emergency

been conducting the war for the British government, a group that included

most of the top ocers in the army and police. In addition, large numbers of

British, Australian, and New Zealand troops continued the hunt for the guer-

rillas.

In late 1957 and 1958 counterinsurgency operations destroyed some of the

remaining guerrilla pockets, which allowed the government to concentrate

its counterguerrilla forces in the few areas where the guerrillas refused to lay

down their arms. Casualties and lack of food led to the surrender of several key

guerrilla leaders, who convinced other guerrillas to surrender and provided

information that led to further military reverses for the insurgency. Five hun-

dred guerrillas surrendered in 1958, more than in any previous year. By the end

of 1958, the number of guerrilla ghters had fallen to 350, which prompted the

Communist Party to move most of its armed forces into southern ailand,

where they could recuperate and launch small attacks into Malaya. Scattered

guerrilla and counterguerrilla operations persisted in the ai-Malay border

region into 1959 and beyond, but the insurgents ceased posing a signicant

threat to the well-being of the country.57

e perceived lessons of the Malayan Emergency have informed much of

the advice provided to American counterinsurgents in the twenty-rst cen-

tury. As the foregoing assessment indicates, these lessons are in need of some

revision. Contrary to popular belief, the ineectiveness of the British counter-

insurgents from 1948 to 1951 did not result from a failure to understand the

problem or to identify appropriate countermeasures. Rather, it resulted from

weak leadership. Following the outburst of Communist violence in June 1948,

the British multiplied the number of policemen, but without sucient at-

tention to the quality of their leaders, committing the common error of pre-

suming that eective forces can be created simply by providing funds and as-

signing a certain number of new personnel. Because of poor leadership, the

expanded police forces were generally inept and, aside from occasional acts of

indiscriminate brutality, inert. rough the Emergency regulations, the British

government denied the people the protections of civil liberties, an appropri-

ate enough response to the Communist threat, but one that allowed abuses to

ourish in the absence of good leadership. e government’s armed forces had

considerably better ocers than the police did at the start of the war, which

translated into vigorous military operations and, in some cases, rapid adap-

tation of tactics to local conditions. Although the police failed to provide the

armed forces with much intelligence on the insurgents, military operations

e Malayan Emergency 131

succeeded in disrupting major guerrilla activities and denying the guerrillas

the military initiative.

e Malayan Emergency demonstrates the critical importance of leader-

ship at the top and the dierences between good and poor leadership at that

level. By refusing to visit the insurgency’s equivalent of front lines—the vil-

lages and outposts and local headquarters—Gurney failed to inspire subor-

dinates in the eld or appraise their performance. Because of Gurney’s pre-

ferred management style and the inferior quality of many junior leaders, the

central headquarters micromanaged and produced an excess of paperwork at

the expense of action. e addition of Briggs, a ne leader, to Gurney’s leader-

ship team failed to remedy this condition because Briggs was not given the

authority required to impose change on sluggish bureaucrats. Nor, at the dis-

trict level, did the district ocers have the latitude to exert strong leadership,

having been placed on interagency committees without the power to override

uncooperative committee members.

When Gerald Templer took the helm in February 1952, he had the good

fortune of receiving supreme authority over all civil and military organiza-

tions, which gave him the freedom of action that Briggs had never possessed.

Templer, in turn, provided freedom to those below him. Although Templer

issued doctrinal publications, he did not attempt to force specic methods

upon local commanders, for he knew that success required autonomous and

adaptive local leaders, capable of using their own judgment to determine

whether, when, and how to apply doctrinal concepts.

By leaving the administrative duties of Kuala Lumpur to others, Templer

was able to devote his time to the more important task of touring the coun-

try, primarily for the purpose of identifying leaders who deserved removal or

promotion. He red civil and military leaders at all levels, without concern

for whether they were pleasant people or what it would do for their careers.

Such callousness can be hard for compassionate people to stomach, but it did

promote the greater good of eective counterinsurgency, and it saved the lives

of counterinsurgents. e police and the civil service beneted the most from

Templer’s pitiless axe, for their leaders had never before been subjected to rig-

orous screening of the sort employed by vigilant military ocers. To ll many

of the holes created by the sackings, Templer brought in proven men from

across the empire, a feat that depended upon a cooperative national govern-

ment and a generally high level of talent among the ocers and ocials pro-

duced by British society and government in years past. Templer’s accomplish-

132 e Malayan Emergency

ments also illustrate superbly the value of energy and charisma in winning

support from both government personnel and the population at large.

Templer did not introduce new counterinsurgency tactics or strategy. He

executed existing tactics and strategy more eectively than before, by chang-

ing and inspiring the eld commanders. rough this approach, Templer in-

creased the initiative and inventiveness of the armed forces. e Special Branch

of the police acquired much more intelligence thanks to Templer’s addition

of talented intelligence ocers, and that intelligence presented new opportu-

nities for the armed forces to eliminate Communists. Population relocation,

which initially failed to stem the insurgency because of inadequate adminis-

trators and security forces, thrived under Templer because the new leaders of

the civil service, the police, and the Home Guard possessed the attributes re-

quired to gain control of the resettlement areas and prevent misdeeds by local

personnel. e government’s leaders gained the support of much of the rural

Chinese population through the establishment of security and the demonstra-

tion of integrity and empathy in governance—and not through the institution

of social and economic reforms.

One more critical and underappreciated aspect of the Malayan Emergency

was the strong performance of indigenous forces under foreign command-

ers. Both Templer, as British high commissioner, and Tunku Abdul Rahman,

as the prime minister of independent Malaya, attained favorable outcomes

by putting British and other foreign ocers into leadership positions in the

Malayan military, police, civil service, and Home Guard. Choosing good gov-

ernment over self-government in the short term, they defused the immediate

Communist menace and ultimately attained a peace that would provide a long

term in which Malayans could work on self-government free of the scourge

of subversion.

133

I

n the early twentieth century, as in previous centuries, most of Vietnam’s

leaders belonged to a very small elite that exceeded the rest of the popula-

tion in social status, education, and wealth. Although the French had par-

titioned Vietnam into three colonies in the late nineteenth century, they had

not displaced the Vietnamese elite or fundamentally altered its relationship

to the Vietnamese masses. Concentrated in the urban population centers of

Vietnam, the members of the elite became more Westernized and modernized

with each year of French colonization, widening the gulf that separated them

from the peasants, who composed the vast majority of the populace.

As fate would have it, however, South Vietnam’s rst president, Ngo Dinh

Diem, grew up astride this gulf. Diem’s father had served in the imperial court

as a traditional mandarin ocial, but he quit out of opposition to French poli-

cies, moved his family to the countryside, and took up farming. Diem learned

to grow rice in the premodern way, driving the plow with a water bualo.

At the same time, he gained an understanding of the Vietnamese peasant’s

mind, giving him a decided advantage over the Westernized Vietnamese elites

of Hanoi, Saigon, and other cities who aspired to guide the country’s political

course.

Diem attended the School for Law and Administration in Hanoi and n-

ished at the head of his class, which brought him an appointment as a district

chief, a position of considerable authority. Riding a horse in mandarin garb,

Diem crisscrossed his district to administer public projects and resolve dis-

putes. A devout Catholic who shunned worldly possessions, he projected an

CHAPTER 7

e Vietnam War