Moyar Mark. A Question of Command: Counterinsurgency from the Civil War to Iraq

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

164 e Vietnam War

ment, and supplies required to repel a massive enemy force, which, thanks to

its more reliable allies, possessed state-of-the-art artillery, 600 tanks, and all

the oil and ammunition they needed. e nal defeat of South Vietnam came

on April 30, 1975, when a North Vietnamese tank crashed through the gate of

the Presidential Palace in Saigon. South Vietnamese leaders who had not es-

caped or perished were either executed immediately or incarcerated for many

years in “reeducation camps,” where huge numbers died.

For those pondering counterinsurgency present and future, the Vietnam

War illuminates the challenges of constructing new security forces from the

ruins of the old. As South Vietnam attempted to build police, militia, and

military forces aer the armistice in 1954, leadership development constituted

the most formidable task by far. Until President Diem could raise a new crop

of leaders, he had to rely on the leaders inherited from the French colonial

regime, who were generally so bad that Diem could not wring good perfor-

mances from them through any amount of exhortation, dictation of counter-

insurgency principles, or micromanagement. Recruiting a new generation of

leaders and providing them with sucient experience for important counter-

insurgency commands took seven years.

Once this new group of leaders was ready, Diem came up with creative

organizational devices to advance them past older leaders who, being human,

were averse to relinquishing their powers. He channeled many of the younger

leaders into a new organization, the Republican Youth, which had a chain of

command that bypassed stagnant national ministries and village administra-

tions. He ooded the Ministry of Defense with new talent and transferred con-

trol of a vital militia force, the Civil Guard, to that ministry aer overcoming

long-standing American opposition to the transfer, thereby circumventing the

Ministry of the Interior.

Americans regularly denounced South Vietnam’s presidents for appoint-

ing certain commanders for reasons of political loyalty rather than merit, but

the criticism was oen misplaced. e president needed loyal armed forces

in a country with powerful centrifugal forces. Diem would have been forced

from power well before 1963 had he not enjoyed the support of key military

commanders, and he would have been replaced by someone of lesser quality

who would have purged good ocers, as indeed happened when the military

overthrew him in 1963. In further illustration of the perils of a change in gov-

ernment, the post-Diem purge intensied rivalries and animosities within the

South Vietnamese elites, fostering additional coups and purges that laid the

e Vietnam War 165

South Vietnamese leadership so low as to invite a North Vietnamese invasion

and require an emergency American intervention. Any South Vietnamese

president had to consider both loyalty and merit in appointments and strive

for a balance that enabled the government to withstand attacks from without

and from within.

Purely merit-based selection worked very well on a small scale in the one

South Vietnamese organization with leaders selected directly by Americans,

the Provincial Reconnaissance Units. By scrutinizing the leadership quali-

ties of South Vietnamese ocers and disregarding political considerations,

the Americans consistently installed superb leaders in these units. In the case

of the Combined Action Platoons, South Vietnamese militiamen took their

orders from American commanders, which was not quite as eective be-

cause of barriers of language and culture but still elicited strong performances

from militiamen, provided that the commanders had the requisite leadership

traits.

At various times in the war, outside observers advocated direct American

control of the entire South Vietnamese armed forces, a very alluring course

of action in light of the successes of the Provincial Reconnaissance Units and

the Combined Action Platoons. Top South Vietnamese and American leaders

consistently scotched this proposal, however, viewing it as an aront to South

Vietnamese sovereignty and nationalism and as an impediment to South Viet-

namese self-suciency. Both South Vietnamese and Americans viewed the

U.S. presence in Vietnam as limited in duration, which meant that the South

Vietnamese government had to learn how to choose its own commanders. In

addition, the South Vietnamese understood their country’s internal politics

and political personalities far better than the Americans did, giving them a de-

cided advantage in judging the political impact of command appointments, al-

though the Americans sometimes did play an invaluable role in recommend-

ing changes of commanders.

At the highest level of the South Vietnamese government, the United States

wielded a strong positive inuence when the top American ocials in Saigon

enjoyed good personal relationships with the South Vietnamese president and

did not try to pressure him into adopting American solutions to his problems.

Included in this category of Americans were Edward Lansdale and Samuel

Williams, who helped Diem tackle unfamiliar political and military problems,

and Paul Harkins and Creighton Abrams, who motivated Diem and ieu,

respectively, to attack the enemy aggressively and remove weak ocers.

166 e Vietnam War

Americans who did not build strong personal relationships with the South

Vietnamese, like Elbridge Durbrow and Henry Cabot Lodge, obtained scant

cooperation from the South Vietnamese and, through pressure tactics, oen

caused the South Vietnamese to do the opposite of what was desired. Unable to

see South Vietnam through Vietnamese eyes, these Americans further under-

mined their standing with the Vietnamese by promoting a host of counter-

productive measures. Among the most shopworn was a “broadening” of the

South Vietnamese government by installing representatives of every popu-

lation segment. On the few occasions when the South Vietnamese felt su-

ciently indebted to the Americans to follow this advice, they came to regret it,

for the representatives were incompetent or concerned only with advancing

their own faction’s parochial agendas.

General William Westmoreland’s critical aw was his inattention to the

quality of South Vietnamese military commanders. Permitting the South Viet-

namese to solve their leadership problems entirely on their own promoted

South Vietnam’s sense of independence, but it forfeited the very large gains

that could be had by promoting the replacement of inferior commanders,

gains that Westmoreland’s successor realized. Westmoreland exemplied the

leader whose compassion for subordinates prevented him from relieving those

who, for the greater good of the cause and the lives of their men, deserved to

be relieved. Westmoreland, moreover, did not give due consideration to the

problems created by disunity of command among counterinsurgency agen-

cies. Fortunately for him, others did, and they persuaded President Johnson to

form CORDS, which, by placing civil and military agencies into a single chain

of command, made it possible to achieve close civil-military collaboration and

hence hastened the annihilation of the insurgents.

e activity that most set General Abrams apart from Westmoreland, and

that bore the most fruit, was Abrams’s judicious coaxing of President ieu to

replace commanders. Abrams also sought to alter American tactics by boost-

ing the number of small operations in populous areas, and American forces

did indeed operate much more oen in small units than before, with their

ocers usually demonstrating the necessary attributes of counterinsurgency

leadership. But many of the American forces made few or no tactical changes.

Abrams’s ability to change tactics from the top was seriously constrained by the

ongoing need for large, mobile operations against big North Vietnamese army

units and by his own recognition of the need for decentralized command. e

counterinsurgency as a whole did not undergo a major shi in methods under

e Vietnam War 167

Abrams; the major shi was in the number of American troops allocated to

securing the populous rural areas. e American troops who were transferred

to population security employed essentially the same methods that hundreds

of thousands of South Vietnamese troops were already using.

Much misunderstanding of counterinsurgency in Vietnam has arisen be-

cause of a lack of awareness that Communist armed forces regularly massed

for large conventional attacks, a feature that sharply dierentiated this war

from insurgencies that never advance beyond the guerrilla phase. e inter-

mingling of the Communist regular and irregular forces and the ability of the

regular forces to switch back and forth between regular and irregular warfare

demanded that the counterinsurgents employ mobile conventional forces to

engage enemy regulars, as well as less heavily equipped static forces to keep the

guerrillas out of the villages. At least some of the commanders of the counter-

insurgent conventional forces needed prociency in both regular and irregular

warfare, along with the judgment to know when to use each and the exibility

to transition readily from one to the other.

South Vietnam’s inability to resist the insurgents eectively during certain

periods of the war resulted from neither bad doctrine nor a misunderstanding

of the enemy nor lack of emphasis on nonmilitary programs. It resulted from

bad eld leadership. Variations in the South Vietnamese government’s overall

success against the insurgents coincided exactly with changes in the overall

quality of South Vietnamese leaders—from the sharp upturn in 1962 as new

leaders came of age, to the precipitous drop following the overthrow of Diem

in November 1963, to the slow climb brought on by the installation of the

ieu-Ky government in 1965, to the more dramatic and sustained ascent aer

the Tet Oensive of 1968. How these shis in leadership quality occurred dem-

onstrated one more trend with broad implications: major changes in leader-

ship quality were driven by the actions of the counterinsurgents themselves.

L

e

m

p

a

R

.

G

r

a

n

d

e

d

e

M

i

g

u

e

l

R

.

L

e

m

p

a

T

o

r

o

l

a

R

.

S

u

m

p

u

l

R

.

P

a

z

R

.

Conchagüita I.

M

Cerrón Grande

Reservoir

Ilopango

Lake

Peninsula San

Juan del Gozo

Amapala

Point

Remedios Point

Lake

Coatepeque

Lake

Guya

Septiembre

Reservoir

Lake

Olomega

PACIFIC OCEAN

Nueva

San Salvador

Santa Ana

Chalatenango

La Palma

Cojutepeque

Sensuntepeque

San Francisco

Gotera

San Miguel

El Cuco

San

Vicente

Zacatecoluca

Usulután

La Unión

Corinto

Sonsonate

Ahuachapán

Chalchuapa

San Salvador

HONDURAS

EL SALVADOR

GUATEMALA

0

10

20 kilometers

0

10

20 miles

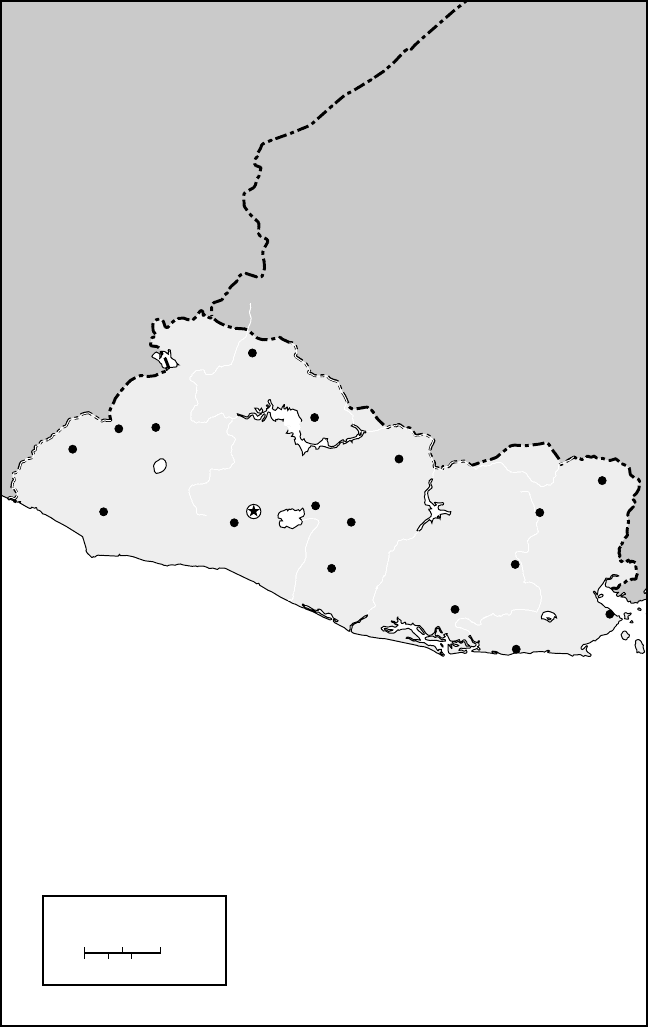

EL SALVADOR, 1980

169

country the size of Massachusetts, with the highest population density

in Latin America, El Salvador had 3.9 million people when war broke

out in 1980. Dominating the country was a small, wealthy elite that

owned 70 percent of the land and relied on the army for protection against

its enemies, foreign and domestic. e army was headed by a dierent small

group of men, who also enjoyed considerable wealth, but they were nouveaux

riches of lower-middle-class birth, which kept them o the invitation lists for

the balls and weddings of El Salvador’s high society.1

Domestic enemies had been on the rise in the 1970s. e peasants were

restive, stirred up by Communists and by preachers of “liberation theology,”

a doctrine that advocated political radicalism by invoking the unusual claim

that Jesus had been a le-wing political activist. Revolutionary fervor gripped

some of the country’s most gied and well-educated youth as radical univer-

sity professors and high-school teachers recruited their students into sub-

versive organizations. But where the revolutionary elites were largely moti-

vated by abstract political and religious ideas, the peasants saw revolution as

the solution to a concrete problem, the misconduct of El Salvador’s security

forces. Devoid of concern for civil liberties and inclined toward cruel and un-

usual punishments, the security forces committed innumerable acts of bru-

tality against suspected rebels and innocent civilians alike.2

When Jimmy Carter became president of the United States in 1977, he de-

clared that America’s allies should aord their peoples all of the rights and

privileges that the United States granted its people. He put the Salvadoran gov-

CHAPTER 8

e Salvadoran Insurgency

A

170 e Salvadoran Insurgency

ernment on notice that it would have to comply with American human rights

standards in order to keep U.S. aid owing into its treasury. e proud Salva-

dorans could not abide such Yankee self-righteousness and intrusiveness, even

if it came from a Georgia peanut farmer rather than a Boston Brahmin or a

Manhattan blueblood, so they refused that condition. e Carter administra-

tion, very uncompromising in its early days, cut o aid.3

In October 1979 the Salvadoran president, General Carlos Humberto

Romero, was ousted by young ocers who shared the Carter administration’s

vision for El Salvador—they favored democracy, respect for human rights,

an end to corruption, and redistribution of land from rich to poor. e new

government reached out to moderates and even to the militant le. But the

junta did little to fulll its bold promises during its rst months in power,

owing to its own shortcomings and the obstruction of conservatives and right-

wing extremists in the armed forces. e junta was unwilling to coerce or oust

these rightists because the traditions of the Salvadoran ocer corps forbade it.

ese traditions, of inordinate importance to the government and the army,

originated in one military school in San Salvador.4

Located in a few cement buildings on a noisy city street, the Salvadoran

military academy looked like a set of warehouses or administrative buildings.

Called the Captain General Gerardo Barrios Military School, it took its name

from a Salvadoran ocer who had led the expulsion of the American adven-

turer William Walker from Nicaragua’s presidency in 1857. All ocer candi-

dates for the army and the three internal security forces—the National Police,

the Treasury Police, and the National Guard—attended the academy and at

graduation became members of a single ocer corps. Admission into the mili-

tary academy was highly competitive. For lower-middle-class boys, it oered

more than any other job or school available to them—cadets received four

years of free education, followed by a well-paid job, higher social status, and

plentiful opportunities for gra.

Instructors at the military academy focused on physical training and ad-

ministered very little training of the mind. e numerous cadets who failed

to reach graduation were thrown out for physical, not mental, inadequacies.

In the classroom, cadets learned primarily by rote memorization, and they

were taught to obey orders without analyzing or questioning them, a type of

instruction that discouraged initiative and le junior ocers with little prepa-

ration for situations that demanded personal judgment or creativity. In devel-

oping innovative methods of warfare, craing propaganda for domestic con-

e Salvadoran Insurgency 171

sumption, and gaining the sympathies of foreigners through public relations,

the academy’s products would be much inferior to their opponents in the in-

surgency that boiled up in 1980.5

During their four years in the academy, Salvadoran army ocers were

imprinted with a loyalty to the ocer corps above all else, and to their own

graduating class, or tanda, above the rest of the ocer corps. is fealty, com-

bined with a cultural aversion to confrontation, kept Salvadoran ocers from

punishing fellow ocers for mistakes and crimes. Even the worst oenses,

such as abetting the enemy or murdering civilians, did not get ocers kicked

out of the ocer corps, although they typically led to assignments as attachés

in obscure and undesirable foreign countries. e culture of the ocer corps

also dictated that ocers avoid making major changes of any kind, so as not

to oend ocers predisposed to the status quo. It was for this reason that the

junta of 1979 declined to implement its ideas on land reform, democracy, and

other political issues in the face of opposition from the rightists.6

ree main revolutionary groups had already engaged in violent oppo-

sition prior to the October 1979 coup. ey held their weapons in abeyance

during the rst months of the new regime, waiting to see whether it would

make good on its vows of change. If, as some insurgents speculated, the fac-

tions in the ocer corps and government set upon each other, the insurgents

could exploit the situation as Lenin had done in Russia in 1917. By the end of

1979, however, the government’s failure to deliver change and its opposition to

radical leists convinced the revolutionaries to pursue their aims by force of

arms.

In early 1980 the junta did get moving on some of the promised reforms,

muting opposition from rightist ocers by securing from the Carter admin-

istration $5.7 million in “non-lethal” military aid, which consisted of trucks,

communications equipment, and uniforms. e junta agreed to the national-

ization of banks and the redistribution of land from well-to-do landowners to

peasants who owned no land. But the government implemented the reforms

sporadically and oen improperly, generating animosity among landowners

and others on the right. Some farmers with small holdings had to relinquish

land, and only 10 percent of the landowners who were stripped of their land

received compensation.7

e drastic character and poor implementation of these reforms came

together with the rise of the insurgency to produce a maelstrom on the po-

litical right. Far-right military ocers maneuvered to relieve reformist ocers

172 e Salvadoran Insurgency

of their commands and send them abroad as embassy or consulate attachés.

ey sanctioned, and in some instances participated in, what became known

as death squads. Composed of soldiers and other militant citizens dressed in

civilian garb, the death squads gunned down suspected insurgents and insur-

gent supporters on a large scale. At times, soldiers were brazen enough to per-

petrate such murders in uniform. According to most American sources, the

large majority of the estimated 8,000 to 9,000 civilians killed in 1980 were the

victims of either rightist death squads or government forces.8

Over in Cuba, Fidel Castro was working to unite the Salvadoran leists

under Communist leadership, in the belief that El Salvador was an impor-

tant battleeld in the struggle to spread Communism across Latin America.

In December 1979, Castro had brought a handful of Salvadoran revolutionary

groups to Havana and encouraged them to unify, which led to the formation

in October 1980 of a unied front organization, the Farabundo Martí National

Liberation Front (FMLN). Named aer a famed Salvadoran Communist, the

FMLN was avowedly Marxist-Leninist in its ideology.9

e depletion of the ranks of the insurgents by the Salvadoran military

and the death squads in 1980 convinced Castro and the FMLN leadership that

a mighty oensive had to be launched in the near future, while the revolution-

ary organizations still had some life in them.10 Castro and Nicaraguan Com-

munists from the Sandinista regime assisted the FMLN in planning the oen-

sive, which they dubbed the “nal oensive” in the expectation that it would

overthrow the Salvadoran government in short order. During the last months

of 1980, insurgent forces trained for the oensive in Cuba, and both Cuba and

Nicaragua provided the insurgents with weapons to carry out the attacks. e

oensive was scheduled to begin on January 10, 1981, and end before Ronald

Reagan’s January 20 inauguration as Carter’s successor, in order to seize the

prize before the United States could increase its military assistance—the rhe-

toric of the staunchly anti-Communist Reagan had made clear that he would

be more supportive of the Salvadoran government than Carter had been. “It is

necessary,” the insurgents resolved in early January, “to launch now the battles

for the great general oensive of the Salvadoran people before that fanatic

Ronald Reagan takes over the presidency of the United States.”11

e “nal oensive” began on January 10 with simultaneous attacks on

government oces and military installations across El Salvador. Surround-

ing the government’s armed forces at xed positions, the insurgents attacked

head-on, orange re owing from their Communist-bloc automatic ries and

e Salvadoran Insurgency 173

submachine guns. Insurgent leaders had hoped that reformist military ocers

and urban civilians would ock to their side, and they might have succeeded if

that hope had been realized. As it turned out, however, neither group assisted

the revolutionaries in appreciable numbers. e army’s ocer corps, to the

surprise of its detractors, displayed resolution and competence in defending

the oensive’s targets, preventing the insurgents from overrunning more than

a few.12

e situation, nevertheless, seemed dire enough at rst that Carter, on

January 13, chose to restore all nonlethal military aid to the Salvadoran gov-

ernment in spite of his ongoing dissatisfaction with Salvadoran human rights

practices. e next day, the U.S. National Security Council approved $5.9 mil-

lion in lethal aid, the rst such aid since 1977, and Carter used the emergency

provisions of the Foreign Assistance Act to send the aid without congressional

authorization. On January 16, in another agonizing decision, Carter suspended

aid to Nicaragua because of accumulating evidence that the Sandinista gov-

ernment was transporting arms to the Salvadoran insurgents, ending an ill-

starred policy of courting the Communist Sandinistas with aid and goodwill.13

Having begun his term deploring the “inordinate fear of Communism which

once led us to embrace any dictator who joined us in that fear,” Carter ended

his presidency supporting undemocratic anti-Communists in El Salvador and

Nicaragua, based on a well-justied fear of Communist expansionism.14

e aid authorized by Carter had no impact on the outcome of the oen-

sive, for the insurgents abandoned their attacks aer just one week and re-

treated, with thoroughly deated spirits, into the countryside. Aside from a

few guerrilla and terrorist attacks here and there, they spent the next months

developing revolutionary base areas in the mountains and the jungles where

government forces did not venture. ey made logistical preparations for

future oensive actions and sent their best cadres for military training in Cuba

and Vietnam, which, along with Nicaragua, were to be their principal sup-

pliers of weapons and ammunition in the coming years.15

e Salvadoran government, meanwhile, doubled the size of its army,

from 10,000 to 20,000, and sent soldiers out to cut the insurgency’s supply

lines and kill insurgents and their supporters. is approach would have ac-

complished a good deal if the soldiers had executed it with resolve and skill,

but they manifestly did not. Salvadoran ocers, who were assigned to com-

mands based on seniority and political reliability, were generally lacking in

aggressiveness, dedication, and basic military prociency. ey avoided night