Nigel S., Chambers S., Johnson R. Operations Management

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

plastic, and appalling colours; a construction of hardened

chewing-gum and idiot folklore taken straight out of comic

books written for obese Americans’. However, as some

commentators noted, the cultural arguments and anti-

Americanism of the French intellectual elite did not seem

to reflect the behaviour of most French people, who ‘eat

at McDonald’s, wear Gap clothing, and flock to American

movies’.

Designing Disneyland Resort Paris

Phase 1 of the Euro Disney Park was designed to have

29 rides and attractions and a championship golf course

together with many restaurants, shops, live shows and

parades as well as six hotels. Although the park was

designed to fit in with Disney’s traditional appearance and

values, a number of changes were made to accommod-

ate what was thought to be the preferences of European

visitors. For example, market research indicated that Euro-

peans would respond to a ‘wild west’ image of America.

Therefore, both rides and hotel designs were made to

emphasize this theme. Disney was also keen to diffuse

criticism, especially from French left-wing intellectuals

and politicians, that the design of the park would be too

‘Americanized’ and would become a vehicle for American

‘cultural imperialism’. To counter charges of American imper-

ialism, Disney gave the park a flavour that stressed the

European heritage of many of the Disney characters, and

increased the sense of beauty and fantasy. They were, after

all, competing against Paris’s exuberant architecture and

sights. For example, Discoveryland featured storylines from

Jules Verne, the French author. Snow White (and her dwarfs)

was located in a Bavarian village. Cinderella was located

in a French inn. Even Peter Pan was made to appear more

‘English Edwardian’ than in the original US designs.

Because of concerns about the popularity of American

‘fast food’, Euro Disney introduced more variety into its

restaurants and snack bars, featuring foods from around the

world. In a bold publicity move, Disney invited a number of

top Paris chefs to visit and taste the food. Some anxiety was

also expressed concerning the different ‘eating behaviour’

between Americans and Europeans. Whereas Americans

preferred to ‘graze’, eating snacks and fast meals through-

out the day, Europeans generally preferred to sit down and

eat at traditional meal times. This would have a very signi-

ficant impact on peak demand levels on dining facilities.

A further concern was that in Europe (especially French)

visitors would be intolerant of long queues. To overcome

this, extra diversions such as films and entertainments

were planned for visitors as they waited in line for a ride.

Before the opening of the park, Euro Disney had to

recruit and train between 12,000 and 14,000 permanent

and around 5,000 temporary employees. All these new

employees were required to undergo extensive training in

order to prepare them to achieve Disney’s high standard

of customer service as well as understand operational

routines and safety procedures. Originally, the company’s

objective was to hire 45 per cent of its employees from

France, 30 per cent from other European countries, and

15 per cent from outside of Europe. However, this proved

difficult and when the park opened around 70 per cent

of employees were French. Most cast members were paid

around 15 per cent above the French minimum wage.

An information centre was opened in December 1990

to show the public what Disney was constructing. The

‘casting centre’ was opened on 1 September 1991 to

recruit the ‘cast members’ needed to staff the park’s

attractions. But the hiring process did not go smoothly. In

particular, Disney’s grooming requirements that insisted

on a ‘neat’ dress code, a ban on facial hair, set standards

for hair and finger nails, and an insistence on ‘appropriate

undergarments’ proved controversial. Both the French

press and trade unions strongly objected to the grooming

requirements, claiming they were excessive and much

stricter than was generally held to be reasonable in France.

Nevertheless, the company refused to modify its groom-

ing standards. Accommodating staff also proved to be

a problem, when the large influx of employees swamped

the available housing in the area. Disney had to build its

own apartments as well as rent rooms in local homes just

to accommodate its employees. Notwithstanding all the

difficulties, Disney did succeed in recruiting and training all

its cast members before the opening.

The park opens

The park opened to employees, for testing during late

March 1992, during which time the main sponsors and their

families were invited to visit the new park, but the opening

was not helped by strikes on the commuter trains lead-

ing to the park, staff unrest, threatened security problems

(a terrorist bomb had exploded the night before the

opening) and protests in surrounding villages that demon-

strated against the noise and disruption from the park.

The opening day crowds, expected to be 500,000, failed

to materialize, however, and at close of the first day only

50,000 people had passed through the gates. Disney had

expected the French to make up a larger proportion of

visiting guests than they did in the early days. This may

have been partly due to protests from French locals who

feared their culture would be damaged by Euro Disney.

Also, all Disney parks had traditionally been alcohol-free.

To begin with, Euro Disney was no different. However, this

was extremely unpopular, particularly with French visitors

who like to have a glass of wine or beer with their food.

But whatever the cause the low initial attendance was very

disappointing for the Disney Company.

It was reported that, in the first 9 weeks of operation,

approximately 1,000 employees left Euro Disney, about

one half of whom ‘left voluntarily’. The reasons cited for

leaving varied. Some blamed the hectic pace of work and

the long hours that Disney expected. Others mentioned

the ‘chaotic’ conditions in the first few weeks. Even Disney

conceded that conditions had been tough immediately after

Part Two Design

164

M06A_SLAC0460_06_SE_C06A.QXD 10/20/09 9:27 Page 164

the park opened. Some leavers blamed Disney’s apparent

difficulty in understanding ‘how Europeans work’. ‘We can’t

just be told what to do, we ask questions and don’t all

think the same.’ Some visitors who had experience of the

American parks commented that the standards of service

were noticeably below what would be acceptable in

America. There were reports that some cast members were

failing to meet Disney’s normal service standard: ‘even on

the opening weekend some clearly couldn’t care less . . .

My overwhelming impression . . . was that they were out of

their depth. There is much more to being a cast member

than endlessly saying “Bonjour”. Apart from having a

detailed knowledge of the site, Euro Disney staff have the

anxiety of not knowing in what language they are going to

be addressed . . . Many were struggling.’

It was also noticeable that different nationalities

exhibited different types of behaviour when visiting the

park. Some nationalities always used the waste bins while

others were more likely to drop litter on the floor. Most

noticeable were differences in queuing behaviour. Northern

Europeans tend to be disciplined and content to wait for

rides in an orderly manner. By contrast some Southern

European visitors ‘seem to have made an Olympic event

out of getting to the ticket taker first’. Nevertheless, not all

reactions were negative. European newspapers also

quoted plenty of positive reaction from visitors, especially

children. Euro Disney was so different from the existing

European theme parks, with immediately recognizable

characters and a wide variety of attractions. Families who

could not afford to travel to the United States could now

interact with Disney characters and ‘sample the experi-

ence at far less cost’.

The next 15 years

By August 1992 estimates of annual attendance figures were

being drastically cut from 11 million to just over 9 million.

EuroDisney’s misfortunes were further compounded in

late 1992 when a European recession caused property

prices to drop sharply, and interest payments on the large

start-up loans taken out by EuroDisney forced the com-

pany to admit serious financial difficulties. Also the cheap

dollar resulted in more people taking their holidays in

Florida at Walt Disney World. At the first anniversary of

the park’s opening, in April 1993, Sleeping Beauty’s Castle

was decorated as a giant birthday cake to celebrate the

occasion; however, further problems were approaching.

Criticized for having too few rides, the roller coaster ‘Indiana

Jones and the Temple of Peril’ was opened in July. This was

the first Disney roller coaster that included a 360-degree

loop, but just a few weeks after opening emergency brakes

locked on during a ride, causing some guest injuries. The

ride was temporarily shut down for investigations. Also in

1993 the proposed Euro Disney phase 2 was shelved due

to financial problems. This meant Disney MGM Studios

Europe and 13,000 hotel rooms would not be built to the

original 1995 deadline originally agreed upon by the Walt

Disney Company. However, Discovery Mountain, one of

the planned phase 2 attractions, did get approval.

By the start of 1994 rumours were circulating that the

park was on the verge of bankruptcy. Emergency crisis

talks were held between the banks and backers with things

coming to a head during March when Disney offered the

banks an ultimatum. It would provide sufficient capital for

the park to continue to operate until the end of the month,

but unless the banks agreed to restructure the park’s $1bn

debt, the Walt Disney Company would close the park, and

walk away from the whole European venture, leaving the

banks with a bankrupt theme park and a massive expanse

of virtually worthless real estate. Michael Eisner, Disney’s

CEO, announced that Disney was planning to pull the plug

on the venture at the end of March 1994 unless the banks

were prepared to restructure the loans. The banks agreed

to Disney’s demands.

In May 1994 the connection between London and Marne

La Vallée was completed, along with a TGV link, providing

a connection between several major European cities. By

August the park was starting to find its feet at last, and

all of the park’s hotels were fully booked during the peak

holiday season. Also, in October, the park’s name was

officially changed from EuroDisney to ‘Disneyland Paris’

in order to ‘show that the resort now was named much

more like its counterparts in California and Tokyo’. The

end-of-year figures for 1994 showed encouraging signs

despite a 10% fall in attendance caused by the bad publicity

over the earlier financial problems. For the next few years

new rides continued to be introduced. 1995 saw the opening

of the new roller coaster, ‘Space Mountain de la Terre à

la Lune’, and Euro Disney did announce its first annual

operating profit in November 1995. New attractions were

added steadily, but in 1999 the planned Christmas and

New Year celebrations are disrupted when a freak storm

caused havoc, destroying the Mickey Mouse glass statue

that had just been installed for the Lighting Ceremony and

many other attractions.

Disney’s ‘Fastpass’ system was introduced in 2000: a

new service that allowed guests to use their entry passes

to gain a ticket at certain attractions and return at the

time stated and gain direct entry to the attraction without

queuing. Two new attractions were also opened, ‘Indiana

Jones et la Temple du Peril’ and ‘Tarzan le Recontre’

starring a cast of acrobats along with Tarzan, Jane and all

their jungle friends with music from the movie in different

European languages. In 2001 the ‘ImagiNations Parade’ is

replaced by the ‘Wonderful World of Disney Parade’ which

receives some criticism for being ‘less than spectacular’ with

only 8 parade floats. Also Disney’s ‘California Adventure’

was opened in California. The Paris resort’s 10th anniver-

sary saw the opening of the new Walt Disney Studios Park

attraction, based on a similar attraction in Florida that had

already proved to be a success.

André Lacroix from Burger King was appointed as CEO

of Disneyland Resort Paris in 2003, to ‘take on the challenge

Chapter 6 Supply network design

165

➔

M06A_SLAC0460_06_SE_C06A.QXD 10/20/09 9:27 Page 165

of a failing Disney park in Europe and turn it around’.

Increasing investment, he refurbished whole sections of the

park and introduced the Jungle Book Carnival in February

to increase attendance during the slow months. By 2004

attendance had increased but the company announced

that it was still losing money. And even the positive news

of 2006, although generally well received still left questions

unanswered. As one commentator put it, ‘Would Disney,

the stockholders, the banks, or even the French government

make the same decision to go ahead if they could wind

the clock back to 1987? Is this a story of a fundamentally

flawed concept, or was it just mishandled?’

Questions

1 What markets are the Disney resorts and parks

aiming for?

2 Was Disney’s choice of the Paris site a mistake?

3 What aspects of their parks’ design did Disney change

when it constructed Euro Disney?

4 What did Disney not change when it constructed

Euro Disney?

5 What were Disney’s main mistakes from the

conception of the Paris resort through to 2006?

Part Two Design

166

These problems and applications will help to improve your analysis of operations. You

can find more practice problems as well as worked examples and guided solutions on

MyOMLab at

www.myomlab.com.

A company is deciding between two locations (Location A and Location B). It has six location criteria, the

most important being the suitability of the buildings that are available in each location. About half as important

as the suitability of the buildings are the access to the site and the supply of skills available locally. Half as

important as these two factors are the potential for expansion on the sites and the attractiveness of the area.

The attractiveness of the buildings themselves is also a factor, although a relatively unimportant one, rating

one half as important as the attractiveness of the area. Table 6.7 indicates the scores for each of these factors,

as judged by the company’s senior management. What would you advise the company to do?

1

A company which assembles garden furniture obtains its components from three suppliers. Supplier A provides

all the boxes and packaging material; supplier B provides all metal components; and supplier C provides all

plastic components. Supplier A sends one truckload of the materials per week to the factory and is located

at the position (1,1) on a grid reference which covers the local area. Supplier B sends four truckloads of

components per week to the factory and is located at point (2,3) on the grid. Supplier C sends three truckloads

of components per week to the factory and is located at point (4,3) on the grid. After assembly, all the products

are sent to a warehouse which is located at point (5,1) on the grid. Assuming there is little or no waste

generated in the process, where should the company locate its factory so as to minimize transportation costs?

Assume that transportation costs are directly proportional to the number of truckloads of parts, or finished

goods, transported per week.

A rapid-response maintenance company serves its customers who are located in four industrial estates. Estate A has

15 customers and is located at grid reference (5,7). Estate B has 20 customers and is located at grid reference

(6,3). Estate C has 15 customers and is located at grid reference (10,2) but these customers are twice as likely

to require service as the company’s other customers. Estate D has 10 customers and is located at grid reference

(12,3). At what grid reference should the company be looking to find a suitable location for its service centre?

3

2

Table 6.7 The scores for each factor in the location decision

as judged by the company’s senior management

Location A Location B

Access 4 6

Expansion 6 5

Attractiveness (area) 10 6

Skills supply 5 7

Suitability of buildings 8 7

Attractiveness of buildings 4 6

Problems and applications

M06A_SLAC0460_06_SE_C06A.QXD 10/20/09 9:27 Page 166

A private health-care clinic has been offered a leasing deal where it could lease a CAT scanner at a fixed

charge of A2,000 per month and a charge per patient of A6 per patient scanned. The clinic currently charges

A10 per patient for taking a scan. (a) At what level of demand (in number of patients per week) will the clinic

break even on the cost of leasing the CAT scan? (b) Would a revised lease that stipulated a fixed cost of

A3,000 per week and a variable cost of A0.2 per patient be a better deal?

Visit sites on the Internet that offer (legal) downloadable music using MP3 or other compression formats.

Consider the music business supply chain, (a) for the recordings of a well-known popular music artist, and

(b) for a less well-known (or even largely unknown) artist struggling to gain recognition. How might the

transmission of music over the Internet affect each of these artists’ sales? What implications does electronic

music transmission have for record shops?

Visit the web sites of companies that are in the paper manufacturing/pulp production/packaging industries.

Assess the extent to which the companies you have investigated are vertically integrated in the paper supply

chain that stretches from foresting through to the production of packaging materials.

6

5

4

Chapter 6 Supply network design

167

Carmel, E. and Tjia, P. (2005) Offshoring Information

Technology: Sourcing and Outsourcing to a Global Workforce,

Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. An academic book

on outsourcing.

Chopra, S. and Meindl, P. (2001) Supply Chain Management:

Strategy, Planning and Operations, Prentice Hall, Upper

Saddle River, NJ. A good textbook that covers both strategic

and operations issues.

Dell, M. (with Catherine Fredman) (1999) Direct from Dell:

Strategies that Revolutionized an Industry, Harper Business

London. Michael Dell explains how his supply network

strategy (and other decisions) had such an impact on the

industry. Interesting and readable, but not a critical analysis!

Schniederjans, M.J. (1998) International Facility Location

and Acquisition Analysis, Quorum Books, New York. Very

much one for the technically minded.

Vashistha, A. and Vashistha, A. (2006) The Offshore Nation:

Strategies for Success in Global Outsourcing and Offshoring,

McGraw-Hill Higher Education. Another topical book on

outsourcing.

Selected further reading

www.locationstrategies.com Exactly what the title implies.

Good industry discussion.

www.cpmway.com American location selection site. You can

get a flavour of how location decisions are made.

www.transparency.org A leading site for international busi-

ness (including location) that fights corruption.

www.intel.com More details on Intel’s ‘Copy Exactly’ strategy

and other capacity strategy issues.

www.opsman.org Lots of useful stuff.

www.outsourcing.com Site of the Institute of Outsourcing.

Some good case studies and some interesting reports, news

items, etc.

www.bath.ac.uk/crisps A centre for research in strategic pur-

chasing and supply with some interesting papers.

Useful web sites

Now that you have finished reading this chapter, why not visit MyOMLab at

www.myomlab.com where you’ll find more learning resources to help you

make the most of your studies and get a better grade?

M06A_SLAC0460_06_SE_C06A.QXD 10/20/09 9:27 Page 167

Supplement to

Chapter 6

Forecasting

Introduction

Some forecasts are accurate. We know exactly what time the sun will rise at any given

place on earth tomorrow or one day next month or even next year. Forecasting in a business

context, however, is much more difficult and therefore prone to error. We do not know

precisely how many orders we will receive or how many customers will walk through the

door tomorrow, next month, or next year. Such forecasts, however, are necessary to help

managers make decisions about resourcing the organization for the future.

Forecasting – knowing the options

Simply knowing that demand for your goods or services is rising or falling is not enough in

itself. Knowing the rate of change is likely to be vital to business planning. A firm of lawyers

may have to decide the point at which, in their growing business, they will have to take

on another partner. Hiring a new partner could take months so they need to be able to fore-

cast when they expect to reach that point and then when they need to start their recruitment

drive. The same applies to a plant manager who will need to purchase new plant to deal with

rising demand. She may not want to commit to buying an expensive piece of machinery until

absolutely necessary but in enough time to order the machine and have it built, delivered,

installed and tested. The same is so for governments whether planning new airports or

runway capacity or deciding where and how many primary schools to build.

The first question is to know how far you need to look ahead and this will depend on

the options and decisions available to you. Take the example of a local government where the

number of primary-age children (5–11-year-olds) is increasing in some areas and declining

in other areas within its boundaries. It is legally obliged to provide school places for all such

children. Government officials will have a number of options open to them and they may

each have different lead times associated with them. One key step in forecasting is to know

the possible options and the lead times required to bring them about (see Table S6.1).

Table S6.1 Options available and lead time required for

dealing with changes in numbers of schoolchildren

Options available Lead time required

Hire short-term teachers Hours

Hire staff

Build temporary classrooms

Amend school catchment areas

Build new classrooms

Build new schools Years

M06B_SLAC0460_06_SE_C06B.QXD 10/21/09 13:39 Page 168

Supplement to Chapter 6 Forecasting

169

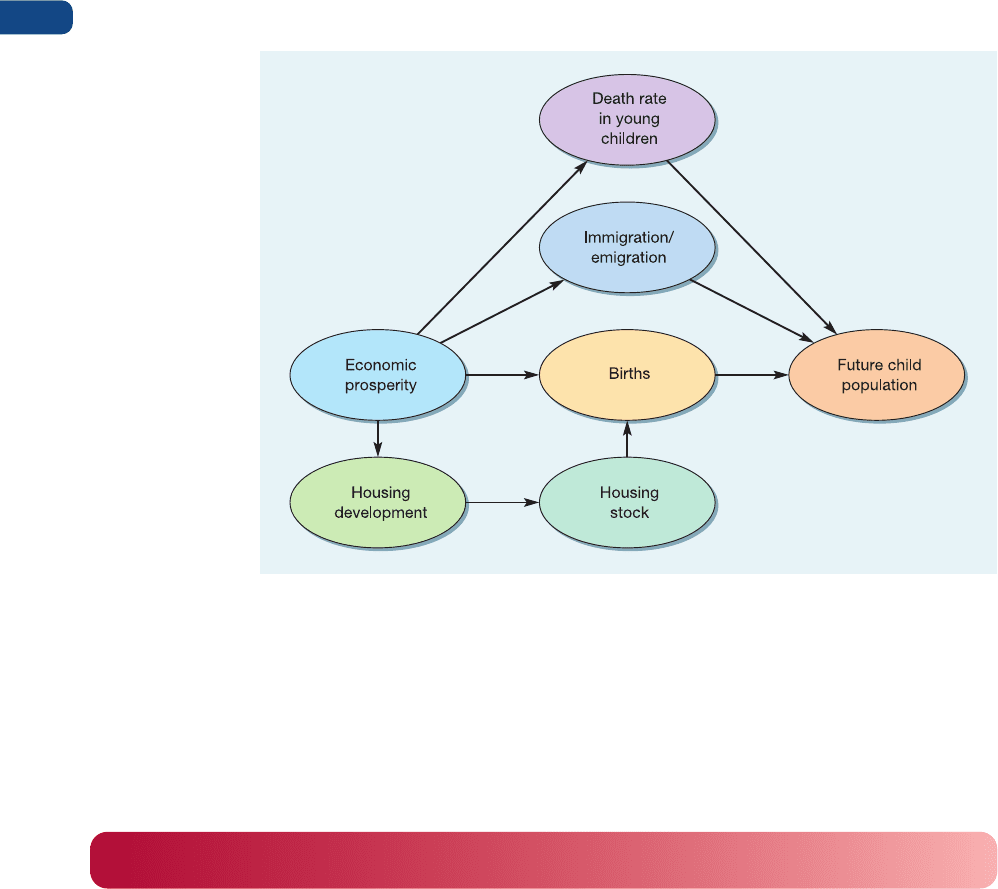

Figure S6.1 Simple prediction of future child population

1 Individual schools can hire (or lay off ) short-term (supply) teachers from a pool not only

to cover for absent teachers but also to provide short-term capacity while teachers are

hired to deal with increases in demand. Acquiring (or dismissing) such temporary cover

may only require a few hours’ notice. (This is often referred to as short-term capacity

management.)

2 Hiring new (or laying off existing) staff is another option but both of these may take months

to complete. (Medium-term capacity management.)

3 A shortage of accommodation may be fixed in the short to medium term by hiring or

buying temporary classrooms. It may only take a couple of weeks to hire such a building

and equip it ready for use.

4 It may be possible to amend catchment areas between schools to try to balance an increas-

ing population in one area against a declining population in another. Such changes may

require lengthy consultation processes.

5 In the longer term new classrooms or even new schools may have to be built. The planning,

consultation, approval, commissioning, tendering, building and equipping process may

take 1 to 5 years depending on the scale of the new build. (Long-term capacity planning –

see Chapter 6.)

Knowing the range of options managers can then decide the timescale for their forecasts;

indeed several forecasts might be needed for the short term, medium term and long term.

In essence forecasting is simple

In essence forecasting is easy. To know how many children may turn up in a local school

tomorrow you can use the number that turned up today. In the long term in order to fore-

cast how many primary-aged children will turn up at a school in five years’ time one need

simply look at the birth statistics for the current year for the school’s catchment area, see

Figure S6.1.

However, such simple extrapolation techniques are prone to error and indeed such approaches

have resulted in some local governments committing themselves to building schools which 5

or 6 years later, when complete, had few children and other schools bursting at the seams with

temporary classrooms and temporary teachers, often resulting in falling morale and declining

educational standards. The reason why such simple approaches are prone to problems is that

there are many contextual variables (see Figure S6.2) which will have a potentially significant

impact on, for example, the school population five years hence. For example:

1 One minor factor in developed countries, though a major factor in developing countries,

might be the death rate in children between birth and 5 years of age. This may be depend-

ent upon location with a slightly higher mortality rate in the poorer areas compared to the

more affluent areas.

2 Another more significant factor is immigration and emigration as people move into or

out of the local area. This will be affected by housing stock and housing developments and

the ebb and flow of jobs in the area and the changing economic prosperity in the area.

M06B_SLAC0460_06_SE_C06B.QXD 10/21/09 13:39 Page 169

Part Two Design

170

Figure S6.2 Some of the key causal variables in predicting child populations

3 One key factor which has an impact on the birth rate in an area is the amount and type

of the housing stock. City-centre tenement buildings tend to have a higher proportion of

children per dwelling, for example, than suburban semi-detached houses. So, not only will

existing housing stock have an impact on the child population but so also will the type of

housing developments under construction, planned and proposed.

Approaches to forecasting

There are two main approaches to forecasting. Managers sometimes use qualitative methods

based on opinions, past experience and even best guesses. There is also a range of qualitative

forecasting techniques available to help managers evaluate trends and causal relationships

and make predictions about the future. Also, quantitative forecasting techniques can be used

to model data. Although no approach or technique will result in an accurate forecast a com-

bination of qualitative and quantitative approaches can be used to great effect by bringing

together expert judgements and predictive models.

Qualitative methods

Imagine you were asked to forecast the outcome of a forthcoming football match. Simply

looking at the teams’ performance over the last few weeks and extrapolating it is unlikely to

yield the right result. Like many business decisions the outcome will depend on many other

factors. In this case the strength of the opposition, their recent form, injuries to players on

both sides, the match location and even the weather will have an influence on the outcome.

A qualitative approach involves collecting and appraising judgements, options, even best guesses

as well as past performance from ‘experts’ to make a prediction. There are several ways this

can be done: a panel approach, the Delphi method and scenario planning.

Qualitative forecasting

Quantitative forecasting

M06B_SLAC0460_06_SE_C06B.QXD 10/21/09 13:39 Page 170

Panel approach

Just as panels of football pundits gather to speculate about likely outcomes so too do politicians,

business leaders, stock market analysts, banks and airlines. The panel acts like a focus group

allowing everyone to talk openly and freely. Although there is the great advantage of several

brains being better than one, it can be difficult to reach a consensus, or sometimes the views

of the loudest or highest status may emerge (the bandwagon effect). Although more reliable

than one person’s views the panel approach still has the weakness that everybody, even the

experts, can get it wrong.

Delphi method

Perhaps the best-known approach to generating forecasts using experts is the Delphi method.

This is a more formal method which attempts to reduce the influences from procedures

of face-to-face meetings. It employs a questionnaire, e-mailed or posted to the experts. The

replies are analysed and summarized and returned, anonymously, to all the experts. The

experts are then asked to re-consider their original response in the light of the replies and

arguments put forward by the other experts. This process is repeated several more times to

conclude with either a consensus or at least a narrower range of decisions. One refinement

of this approach is to allocate weights to the individuals and their suggestions based on,

for example, their experience, their past success in forecasting, other people’s views of their

abilities. The obvious problems associated with this method include constructing an appro-

priate questionnaire, selecting an appropriate panel of experts and trying to deal with their

inherent biases.

1

Scenario planning

One method for dealing with situations of even greater uncertainty is scenario planning.

This is usually applied to long-range forecasting, again using a panel. The panel members

are usually asked to devise a range of future scenarios. Each scenario can then be discussed

and the inherent risks considered. Unlike the Delphi method scenario planning is not neces-

sarily concerned with arriving at a consensus but looking at the possible range of options

and putting plans in place to try to avoid the ones that are least desired and taking action to

follow the most desired.

Quantitative methods

There are two main approaches to qualitative forecasting, time series analysis and causal

modelling techniques.

Time series examine the pattern of past behaviour of a single phenomenon over time

taking into account reasons for variation in the trend in order to use the analysis to forecast

the phenomenon’s future behaviour.

Causal modelling is an approach which describes and evaluates the complex cause–effect

relationships between the key variables (such as in Figure S6.2).

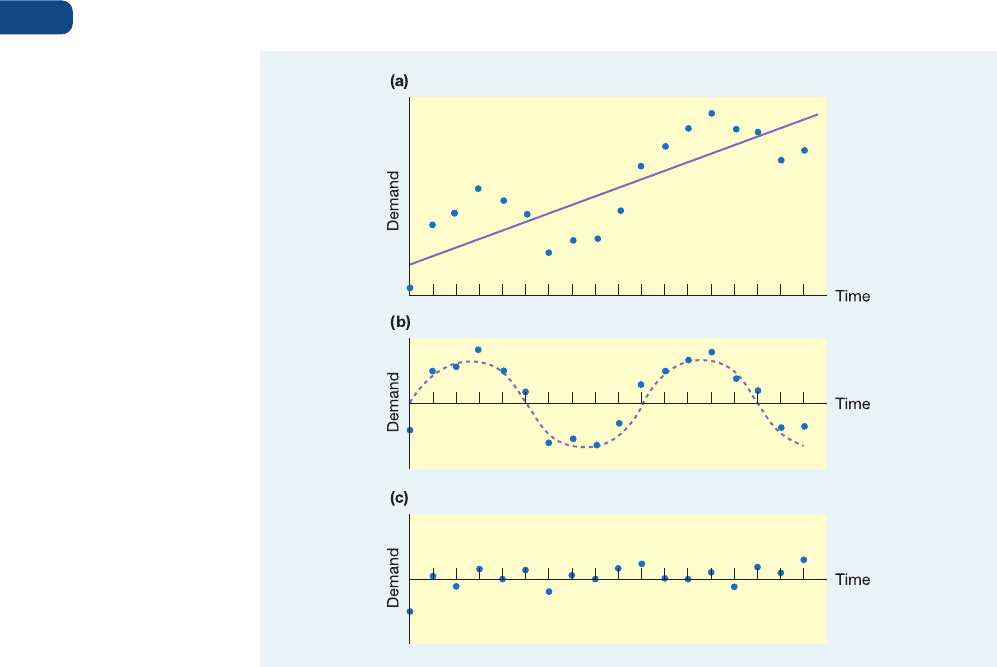

Time series analysis

Simple time series plot a variable over time by removing underlying variations with assign-

able causes use extrapolation techniques to predict future behaviour. The key weakness with

this approach is that it simply looks at past behaviour to predict the future ignoring causal

variables which are taken into account in other methods such as causal modelling or qualita-

tive techniques. For example, suppose a company is attempting to predict the future sales of

a product. The past three years’ sales, quarter by quarter, are shown in Figure S6.3(a). This

series of past sales may be analysed to indicate future sales. For instance, underlying the series

might be a linear upward trend in sales. If this is taken out of the data, as in Figure S6.3(b),

we are left with a cyclical seasonal variation. The mean deviation of each quarter from the

trend line can now be taken out, to give the average seasonality deviation. What remains is

Supplement to Chapter 6 Forecasting

171

Delphi methods

Scenario planning

Time series analysis

Causal modelling

M06B_SLAC0460_06_SE_C06B.QXD 10/21/09 13:39 Page 171

the random variation about the trends and seasonality lines, Figure S6.3(c). Future sales may

now be predicted as lying within a band about a projection of the trend, plus the seasonality.

The width of the band will be a function of the degree of random variation.

Forecasting unassignable variations

The random variations which remain after taking out trend and seasonal effects are without

any known or assignable cause. This does not mean that they do not have a cause, however,

but just that we do not know what it is. Nevertheless, some attempt can be made to forecast

it, if only on the basis that future events will, in some way, be based on past events. We will

examine two of the more common approaches to forecasting which are based on projecting

forward from past behaviour. These are:

● moving-average forecasting;

● exponentially smoothed forecasting.

Moving-average forecasting

The moving-average approach to forecasting takes the previous n periods’ actual demand

figures, calculates the average demand over the n periods, and uses this average as a forecast

for the next period’s demand. Any data older than the n periods plays no part in the next

period’s forecast. The value of n can be set at any level, but is usually in the range 4 to 7.

Example – Eurospeed parcels

Table S6.2 shows the weekly demand for Eurospeed, a Europe-wide parcel delivery company.

It measures demand, on a weekly basis, in terms of the number of parcels which it is given

to deliver (irrespective of the size of each parcel). Each week, the next week’s demand is

Moving-average

forecasting

Exponentially smoothed

forecasting

Part Two Design

172

Figure S6.3 Time series analysis with (a) trend, (b) seasonality and (c) random variation

M06B_SLAC0460_06_SE_C06B.QXD 10/21/09 13:39 Page 172

Supplement to Chapter 6 Forecasting

173

Table S6.2 Moving-average forecast calculated over a

four-week period

Week Actual demand Forecast

(thousands)

20 63.3

21 62.5

22 67.8

23 66.0

24 67.2 64.9

25 69.9 65.9

26 65.6 67.7

27 71.1 66.3

28 68.8 67.3

29 68.4 68.9

30 70.3 68.5

31 72.5 69.7

32 66.7 70.0

33 68.3 69.5

34 67.0 69.5

35 68.6

forecast by taking the moving average of the previous four weeks’ actual demand. Thus if the

forecast demand for week t is F

t

and the actual demand for week t is A

t

, then

F

t

=

For example, the forecast for week 35:

F

35

=

= 68.6

Exponential smoothing

There are two significant drawbacks to the moving-average approach to forecasting. First,

in its basic form, it gives equal weight to all the previous n periods which are used in the

calculations (although this can be overcome by assigning different weights to each of the n

periods). Second, and more important, it does not use data from beyond the n periods over

which the moving average is calculated. Both these problems are overcome by exponential

smoothing, which is also somewhat easier to calculate. The exponential smoothing approach

forecasts demand in the next period by taking into account the actual demand in the current

period and the forecast which was previously made for the current period. It does so accord-

ing to the formula

F

t

= α A

t− 1

+ (1 − x)F

t− 1

where α = the smoothing constant.

The smoothing constant α is, in effect, the weight which is given to the last (and therefore

assumed to be most important) piece of information available to the forecaster. However,

the other expression in the formula includes the forecast for the current period which

included the previous period’s actual demand, and so on. In this way all previous data has a

(diminishing) effect on the next forecast.

Table S6.3 shows the data for Eurospeed’s parcels forecasts using this exponential smooth-

ing method, where α = 0.2. For example, the forecast for week 35 is:

F

35

= 0.2 × 67.0 + 0.8 × 68.3 = 68.04

(72.5 + 66.7 + 68.3 + 67.0)

4

A

t− 2

+ A

t− 3

+ A

t− 4

4

M06B_SLAC0460_06_SE_C06B.QXD 10/21/09 13:39 Page 173