Nigel S., Chambers S., Johnson R. Operations Management

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Part Three Planning and control

484

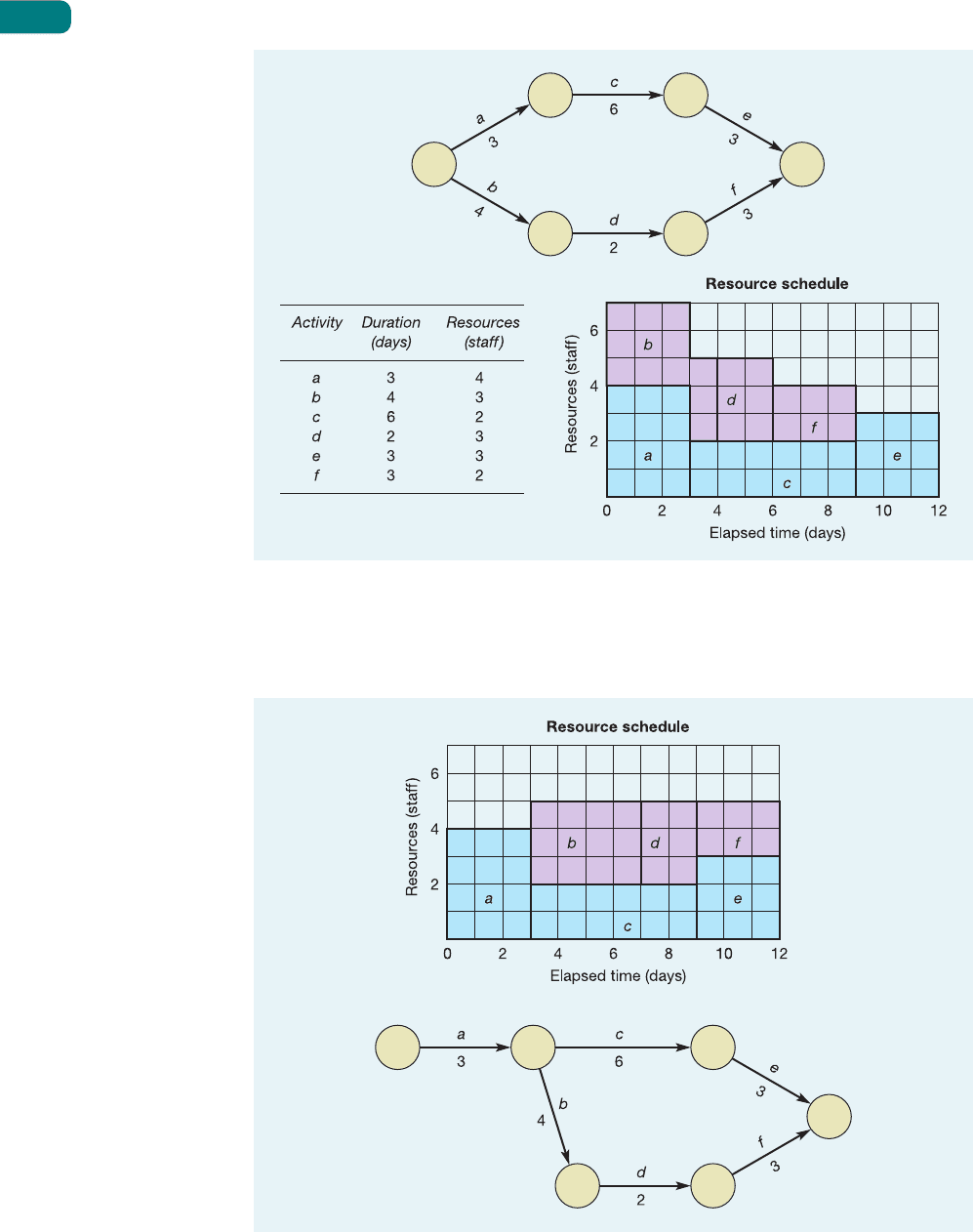

Figure 16.22 Resource profile of a network assuming that all activities are started as soon as

possible

Figure 16.23 Resource profile of a network with non-critical activities delayed to fit

resource constraints; in this case this effectively changes the network logic to make all

activities critical

M16_SLAC0460_06_SE_C16.QXD 10/20/09 15:22 Page 484

Crashing networks

Crashing networks is the process of reducing time spans on critical path activities so that the

project is completed in less time. Usually, crashing activities incurs extra cost. This can be as

a result of:

● overtime working;

● additional resources, such as manpower;

● subcontracting.

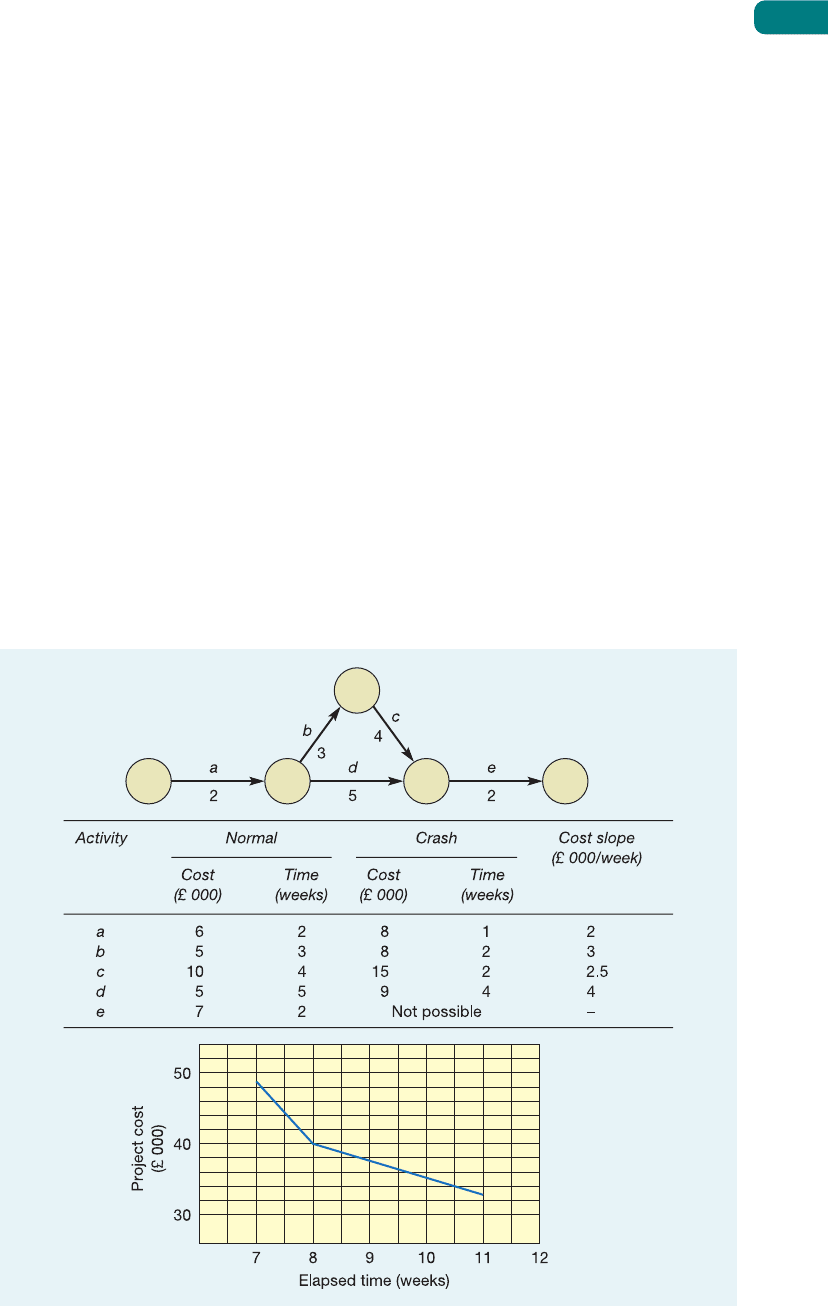

Figure 16.24 shows an example of crashing a simple network. For each activity the dura-

tion and normal cost are specified, together with the (reduced) duration and (increased)

cost of crashing them. Not all activities are capable of being crashed; here activity e cannot

be crashed. The critical path is the sequence of activities a, b, c, e. If the total project time is

to be reduced, one of the activities on the critical path must be crashed. In order to decide

which activity to crash, the ‘cost slope’ of each is calculated. This is the cost per time period

of reducing durations. The most cost-effective way of shortening the whole project then is

to crash the activity on the critical path which has the lowest cost slope. This is activity a, the

crashing of which will cost an extra £2,000 and will shorten the project by one week. After

this, activity c can be crashed, saving a further two weeks and costing an extra £5,000. At this

point all the activities have become critical and further time savings can only be achieved by

crashing two activities in parallel. The shape of the time–cost curve in Figure 16.24 is entirely

typical. Initial savings come relatively inexpensively if the activities with the lowest cost slope

are chosen. Later in the crashing sequence the more expensive activities need to be crashed

and eventually two or more paths become jointly critical. Inevitably by that point, savings in

time can only come from crashing two or more activities on parallel paths.

Crashing

Chapter 16 Project planning and control

485

Figure 16.24 Crashing activities to shorten project time becomes progressively more expensive

M16_SLAC0460_06_SE_C16.QXD 10/20/09 15:22 Page 485

Computer-assisted project management

For many years, since the emergence of computer-based modelling, increasingly sophisticated

software for project planning and control has become available. The rather tedious computa-

tion necessary in network planning can relatively easily be performed by project planning

models. All they need are the basic relationships between activities together with timing

and resource requirements for each activity. Earliest and latest event times, float and other

characteristics of a network can be presented, often in the form of a Gantt chart. More signi-

ficantly, the speed of computation allows for frequent updates to project plans. Similarly, if

updated information is both accurate and frequent, such a computer-based system can also

provide effective project control data. More recently, the potential for using computer-based

project management systems for communication within large and complex projects has been

developed in so-called Enterprise Project Management (EPM) systems.

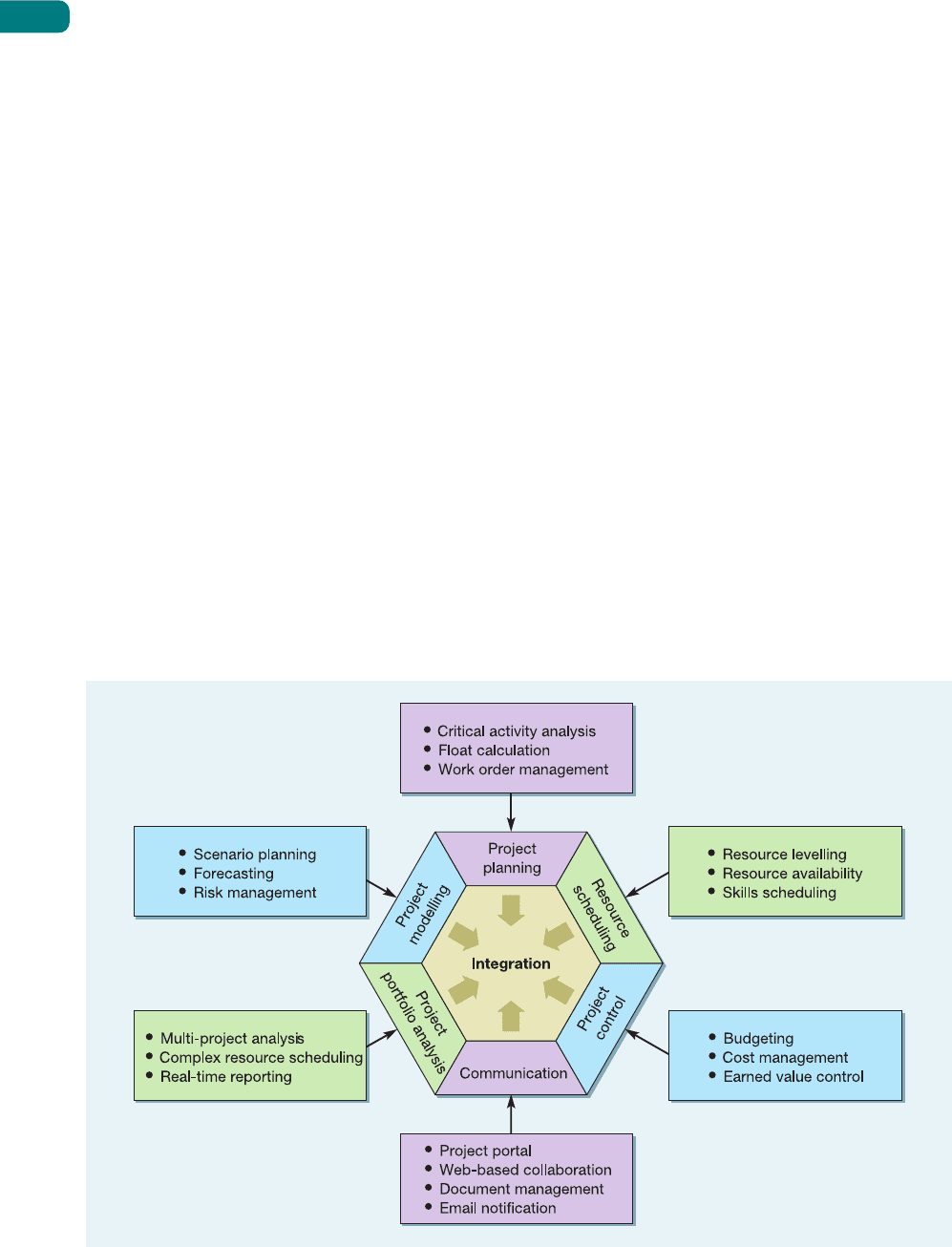

Figure 16.25 illustrates just some of the elements that are integrated within EPM systems.

Most of these activities have been treated in this chapter. Project planning involves critical path

analysis and scheduling, an understanding of float, and the sending of instructions on when

to start activities. Resource scheduling looks at the resource implications of planning decisions

and the way a project may have to be changed to accommodate resource constraints. Project

control includes simple budgeting and cost management together with more sophisticated

earned value control. However, EPM also includes other elements. Project modelling involves

the use of project planning methods to explore alternative approaches to a project, identify-

ing where failure might occur and exploring the changes to the project which may have to

be made under alternative future scenarios. Project portfolio analysis acknowledges that,

for many organizations, several projects have to be managed simultaneously. Usually these

share common resources. Therefore, not only delays in one activity within a project affect

other activities in that project, they may also have an impact on completely different projects

Part Three Planning and control

486

Figure 16.25 Some of the elements integrated in enterprise project management systems

Enterprise Project

Management

M16_SLAC0460_06_SE_C16.QXD 10/20/09 15:22 Page 486

which are relying on the same resource. Finally, integrated EPM systems can help to com-

municate, both within a project and to outside organizations which may be contributing

to the project. Much of this communication facility is web-based. Project portals can allow

all stakeholders to transact activities and gain a clear view of the current status of a project.

Automatic notification of significant milestones can be made by e-mail. At a very basic level,

the various documents that specify parts of the project can be stored in an online library.

Some people argue that it is this last element of communication capabilities that is the most

useful part of EPM systems.

Chapter 16 Project planning and control

487

Summary answers to key questions

Check and improve your understanding of this chapter using self assessment questions

and a personalised study plan, audio and video downloads, and an eBook – all at

www.myomlab.com.

➤ What is a project?

■ A project is a set of activities with a defined start point and a defined end state, which pursues

a defined goal and uses a defined set of resources.

■ All projects can be characterized by their degree of complexity and the inherent uncertainty in

the project.

■ Project management has five stages, four of which are relevant to project planning and control:

understanding the project environments, defining the project, planning the project, technical

execution of the project (not part of project planning and control) and project control.

➤ Why is it important to understand the environment in which a project

takes place?

■ It is important for two reasons. First, the environment influences the way a project is carried

out, often through stakeholder activity. Second, the nature of the environment in which a pro-

ject takes place is the main determinant of the uncertainty surrounding it.

➤ How are projects planned and controlled?

■ Projects can be defined in terms of their objectives (the end state which project manage-

ment is trying to achieve), scope (the exact range of the responsibilities taken on by project

management), and strategy (how project management is going to meet the project objectives).

➤ What is project planning and why is it important?

■ Project planning involves five stages.

– Identifying the activities within a project;

– Estimating times and resources for the activities;

– Identifying the relationship and dependencies between the activities;

– Identifying the schedule constraints;

– Fixing the schedule.

➔

M16_SLAC0460_06_SE_C16.QXD 10/20/09 15:22 Page 487

Part Three Planning and control

488

Introduction

Anuar Kamaruddin, COO of United Photonics Malaysia

(EPM), was conscious that the project in front of him was

one of the most important he had handled for many years.

The number and variety of the development projects under

way within the company had risen sharply in the last few

years, and although they had all seemed important at the

time, this one – the ‘Laz-skan’ project – clearly justified the

description given it by the President of United Photonics

Corporation, the US parent of UPM, ‘the make or break

opportunity to ensure the division’s long term position in

the global instrumentation industry’.

The United Photonics Group

United Photonics Corporation had been founded in the

1920s (as the Detroit Gauge Company), a general instru-

ment and gauge manufacturer for the engineering industry.

By expanding its range into optical instruments in the early

1930s, it eventually moved also into the manufacture of

Case study

United Photonics Malaysia Sdn Bhd

Source: Corbis/Eric K K Yu

■ Project planning is particularly important where complexity of the project is high. The inter-

relationship between activities, resources and times in most projects, especially complex ones,

is such that unless they are carefully planned, resources can become seriously overloaded at

times during the project.

➤ What techniques can be used for project planning?

■ Network planning and Gantt charts are the most common techniques. The former (using either

the activity-on-arrow or activity-on-node format) is particularly useful for assessing the total

duration of a project and the degree of flexibility or float of the individual activities within the

project. The most common method of network planning is called the critical path method (CPM).

■ The logic inherent in a network diagram can be changed by resource constraints.

■ Network planning models can also be used to assess the total cost of shortening a project

where individual activities are shortened.

➤ What is project control and how is it done?

■ The process of project control involves three sets of decisions: how to monitor the project

in order to check its progress, how to assess the performance of the project by comparing

monitored observations to the project plan, and how to intervene in the project in order to make

the changes which will bring it back to plan.

■ Enterprise Project Management systems can be used to integrate all the information needed

to plan and control projects.

M16_SLAC0460_06_SE_C16.QXD 10/20/09 15:22 Page 488

high-precision and speciality lenses, mainly for the photo-

graphic industry. Its reputation as a specialist lens manu-

facturer led to such a growth in sales that by 1969 the

optical side of the company accounted for about 60 per

cent of total business and it ranked as one of the top two

or three optics companies of its type in the world. Although

its reputation for skilled lens-making had not diminished

since then, the instrument side of the company had come

to dominate sales once again in the 1980s and 1990s.

UPM product range

UPM’s product range on the optical side included lenses

for inspection systems which were used mainly in the

manufacture of microchips. These lenses were sold both

to the inspection system manufacturers and to the chip

manufacturers themselves. They were very high-precision

lenses; however, most of the company’s optical products

were specialist photographic and cinema lenses. In addi-

tion about 15 per cent of the company’s optical work was

concerned with the development and manufacture of ‘one

or two off’ extremely high-precision lenses for defence

contracts, specialist scientific instrumentation, and other

optical companies. The Group’s instrument product range

consisted largely of electromechanical assemblies with an

increasing emphasis on software-based recording, display

and diagnostic abilities. This move towards more software-

based products had led the instrument side of the business

towards accepting some customized orders. The growth

of this part of the instrumentation had resulted in a special

development unit being set up: the Customer Services Unit

(CSU) which modified, customized or adapted products

for those customers who required an unusual application.

Often CSU’s work involved incorporating the company’s

products into larger systems for a customer.

In 1995 United Photonics Corporation had set up its

first non-North American facility just outside Kuala Lumpur

in Malaysia. United Photonics Malaysia Sdn Bhd (UPM)

had started by manufacturing subassemblies for Photonics

instrumentation products, but soon had developed into a

laboratory for the modification of United Photonics products

for customers throughout the Asian region. This part of the

Malaysian business was headed by T.S. Lim, a Malaysian

engineer who had taken his postgraduate qualifications at

Stanford and three years ago moved back to his native KL

to head up the Malaysian outpost of the CSU, reporting

directly to Bob Brierly, the Vice-President of Development,

who ran the main CSU in Detroit. Over the last three years,

T.S. Lim and his small team of engineers had gained quite

a reputation for innovative development. Bob Brierly was

delighted with their enthusiasm. ‘Those guys really do know

how to make things happen. They are giving us all a run for

our money.’

The Laz-skan project

The idea for Laz-skan had come out of a project which

T.S. Lim’s CSU had been involved with in 2004. At that

time the CSU had successfully installed a high-precision

Photonics lens into a character recognition system for a

large clearing bank. The enhanced capability which the lens

and software modifications had given had enabled the bank

to scan documents even when they were not correctly

aligned. This had led to CSU proposing the development

of a ‘vision metrology’ device that could optically scan a

product at some point in the manufacturing process, and

check the accuracy of up to twenty individual dimensions.

The geometry of the product to be scanned, the dimensions

to be gauged, and the tolerances to be allowed, could all

be programmed into the control logic of the device. The

T.S. Lim team were convinced that the idea could have

considerable potential. The proposal, which the CSU team

had called the Laz-skan project, was put forward to Bob

Brierly in August 2004. Brierly both saw the potential value

of the idea and was again impressed by the CSU team’s

enthusiasm. ‘To be frank, it was their evident enthusiasm

that influenced me as much as anything. Remember that the

Malaysian CSU had only been in existence for two years at

this time – they were a group of keen but relatively young

engineers. Yet their proposal was well thought out and, on

reflection, seemed to have considerable potential.’

In November 2004 Lim and his team were allocated

funds (outside the normal budget cycle) to investigate the

feasibility of the Laz-skan idea. Lim was given one further

engineer and a technician, and a three-month deadline

to report to the board. In this time he was expected to

overcome any fundamental technical problems, assess

the feasibility of successfully developing the concept into

a working prototype, and plan the development task that

would lead to the prototype stage.

The Lim investigation

T.S. Lim, even at the start of his investigation, had some firm

views as to the appropriate ‘architecture’ for the Laz-skan

project. By ‘architecture’ he meant the major elements of the

system, their functions, and how they related to each other.

The Laz-skan system architecture would consider five major

subsystems: the lens and lens mounting, the vision support

system, the display system, the control logic software, and

the documentation.

T.S. Lim’s first task, once the system’s overall architec-

ture was set, was to decide whether the various com-

ponents in the major subsystems would be developed

in-house, developed by outside specialist companies from

UPM’s specifications, or bought in as standard units and

if necessary modified in-house. Lim and his colleagues

made these decisions themselves, while recognizing that

a more consultative process might have been preferable.

‘I am fully aware that ideally we should have made more

use of the expertise within the company to decide how units

were to be developed. But within the time available we

just did not have the time to explain the product concept,

explain the choices, and wait for already busy people to come

up with a recommendation. Also there was the security

Chapter 16 Project planning and control

489

➔

M16_SLAC0460_06_SE_C16.QXD 10/20/09 15:22 Page 489

Part Three Planning and control

490

Figure 16.26

M16_SLAC0460_06_SE_C16.QXD 10/20/09 15:22 Page 490

system was complicated, there was no great uncertainty in

the individual activities, or therefore the schedule of com-

pletion. If more funds were allocated to their development,

some tasks might even be completed ahead of time.

3 The control software (events 20 to 26, 28)

The control software represented the most complex task,

and the most difficult to plan and estimate. In fact, the soft-

ware development unit had little experience of this type of

work but (partly in anticipation of this type of development)

had recently recruited a young software engineer with

some experience of the type of work which would be

needed for Laz-skan. He was confident that any technical

problems could be solved even though the system needs

were novel, but completion times would be difficult to pre-

dict with confidence.

aspect to think of. I’m sure our employees are to be trusted

but the more people who know about the project, the more

chance there is for leaks. Anyway, we did not see our deci-

sions as final. For example, if we decided that a component

was to be bought in and modified for the prototype build-

ing stage it does not mean that we can’t change our minds

and develop a better component in-house at a later stage.’

By February 2005, TS’s small team had satisfied themselves

that the system could be built to achieve their original tech-

nical performance targets. Their final task before reporting

to Brierly would be to devise a feasible development plan.

Planning the Laz-skan development

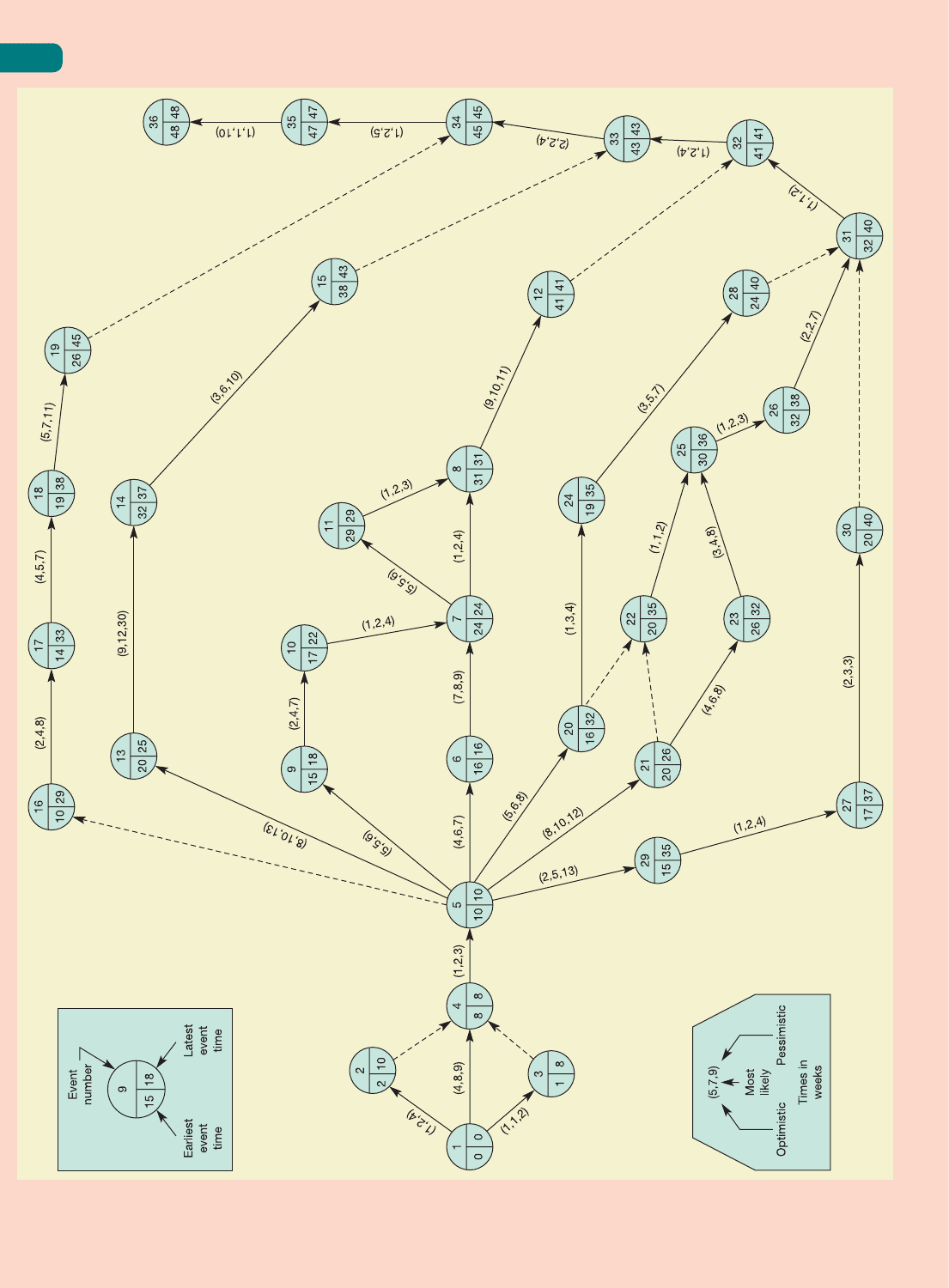

As a planning aid the team drew up a network diagram

for all the major activities within the project from its start

through to completion, when the project would be handed

over to Manufacturing Operations. This is shown in Fig-

ure 16.26 and the complete list of all events in the diagram

is shown in Table 16.4. The duration of all the activities in

the project were estimated either by T.S. Lim or (more often)

by him consulting a more experienced engineer back in

Detroit. While he was reasonably confident in the estimates,

he was keen to stress that they were just that – estimates.

Two draughting conventions on these networks need

explanation. The three figures in brackets by each activity

arrow represent the ‘optimistic’, ‘most likely’ and ‘pessimistic’

times (in weeks) respectively. The left-side figure in the event

circles indicates the earliest time the event could take place

and the figure in the right side of the circles indicates the

latest time the event could take place without delaying the

whole project. Dotted lines represent ‘dummy’ activities.

These are nominal activities which have no time associated

with them and are there either to maintain the logic of the

network or for draughting convenience.

1 The lens (events 5-13-14-15)

The lens was particularly critical since the shape was com-

plex and precision was vital if the system was to perform

up to its intended design specification. T.S. Lim was relying

heavily upon the skill of the Group’s expert optics group in

Pittsburg to produce the lens to the required high tolerance.

Since what in effect was a trial and error approach was

involved in their manufacture, the exact time to manufac-

ture would be uncertain. T.S. Lim realized this.

‘The lens is going to be a real problem. We just don’t

know how easy it will be to make the particular geo-

metry and precision we need. The optics people won’t

commit themselves even though they are regarded as

some of the best optics technicians in the world. It is a

relief that lens development is not amongst the “critical

path” activities.’

2 Vision support system (events 6-7-8-12, 9-5, 11)

The vision support system included many components which

were commercially available, but considerable engineer-

ing effort would be required to modify them. Although the

development design and resting of the vision support

Chapter 16 Project planning and control

491

Table 16.4 Event listing for the Laz-skan project

Event number Event description

1 Start systems engineering

2 Complete interface transient tests

3 Complete compatibility testing

4 Complete overall architecture block and

simulation

5 Complete costing and purchasing tender

planning

6 End alignment system design

7 Receive S/T/G, start synch mods

8 Receive Triscan/G, start synch mods

9 Complete B/A mods

10 Complete S/T/G mods

11 Complete Triscan/G mods

12 Start laser subsystem compatibility tests

13 Complete optic design and specification,

start lens manufacture

14 Complete lens manufacture, start lens

housing S/A

15 Lens S/A complete, start tests

16 Start technical specifications

17 Start help routine design

18 Update engineering mods

19 Complete doc sequence

20 Start vision routines

21 Start interface (tmsic) tests

22 Start system integration compatibility

routines

23 Coordinate trinsic tests

24 End interface development

25 Complete alignment integration routine

26 Final alignment integration data

consolidation

27 Start interface (tmnsic) programming

28 Complete alignment system routines

29 Start tmnsic comparator routines

30 Complete (interface) trinsic coding

31 Begin all logic system tests

32 Start cycle tests

33 Lens S/A complete

34 Start assembly of total system

35 Complete total system assembly

36 Complete final tests and dispatch

➔

M16_SLAC0460_06_SE_C16.QXD 10/20/09 15:22 Page 491

4 Documentation (events 5-16-17-18-19)

A relatively simple subsystem, ‘documentation’ included

specifying and writing the technical manuals, maintenance

routines, online diagnostics, and ‘help desk’ information. It

was a relatively predictable activity, part of which was sub-

contracted to technical writers and translation companies

in Kuala Lumpur.

5 Display system (events 29-27-30)

The simplest of the subsystems to plan, the display system,

would need to be manufactured entirely out of the com-

pany and tested and calibrated on receipt.

Market prospects

In parallel with T.S. Lim’s technical investigation, Sales and

Marketing had been asked to estimate the market potential

of Laz-skan. In a very short time, the Laz-skan project had

aroused considerable enthusiasm within the function, to the

extent that Halim Ramli, the Asian Marketing Vice President,

had taken personal charge of the market study. The major

conclusions from this investigation were:

(a) The global market for Laz-skan type systems was

unlikely to be less than 50 systems per year in 2008,

climbing to more than 200 per year by 2012.

(b) The volume of the market in financial terms was more

difficult to predict, but each system sold was likely to

represent around US$300,000 of turnover.

(c) Some customization of the system would be needed

for most customers. This would mean greater emphasis

on commissioning and post-installation service than

was necessary for UPM’s existing products.

(d) Timing the launch of Laz-skan would be important.

Two ‘windows of opportunity’ were critical. The first

and most important was the major world trade show in

Geneva in April 2006. This show, held every two years,

was the most prominent show-case for new pro-

ducts such as Laz-skan. The second related to the

development cycles of the original equipment manu-

facturers who would be the major customers for

Laz-skan. Critical decisions would be taken in the fall

of 2006. If Laz-skan was to be incorporated into these

companies’ products it would have to be available

from October 2006.

The Laz-skan go ahead

At the end of February 2005 UPM considered both the

Lim and Ramli reports. In addition estimates of Laz-skan’s

manufacturing costs had been sought from George

Hudson, the head of Instrument Development. His estimates

indicated that Laz-skan’s operating contribution would be

far higher than the company’s existing products. The board

approved the immediate commencement of the Laz-skan

development through to prototype stage, with an initial

development budget of US$4.5 m. The objective of the

project was to, ‘build three prototype Laz-skan systems to

be “up and running” for April 2006’.

The decision to go ahead was unanimous. Exactly how

the project was to be managed provoked far more discus-

sion. The Laz-skan project posed several problems. First,

engineers had little experience of working on such a major

project. Second, the crucial deadline for the first batch of

prototypes meant that some activities might have to be

been accelerated, an expensive process that would need

careful judgement. A very brief investigation into which

activities could be accelerated had identified those where

acceleration definitely would be possible and the likely

cost of acceleration (Table 16.5). Finally, no one could agree

either whether there should be a single project leader,

which function he or she should come from, or how senior

the project leader should be. Anuar Kamaruddin knew that

these decisions could affect the success of the project,

and possibly the company, for years to come.

Questions

1 Who do you think should manage the Laz-skan

Development Project?

2 What are the major dangers and difficulties that will be

faced by the development team as they manage the

project towards its completion?

3 What can they do about these dangers and difficulties?

Part Three Planning and control

492

Table 16.5 Acceleration opportunities for Laz-skan

Activity Acceleration Likely maximum Normal most

cost activity time, likely time

(US$/week) with acceleration (weeks)

(weeks)

5–6 23,400 3 6

5–9 10,500 2 5

5–13 25,000 8 10

20–24 5,000 2 3

24–28 11,700 3 5

33–34 19,500 1 2

M16_SLAC0460_06_SE_C16.QXD 10/20/09 15:22 Page 492

Chapter 16 Project planning and control

493

These problems and applications will help to improve your analysis of operations. You

can find more practice problems as well as worked examples and guided solutions on

MyOMLab at

www.myomlab.com.

The activities, their durations and precedences for designing, writing and installing a bespoke computer

database are shown in Table 16.6. Draw a Gantt chart and a network diagram for the project and calculate the

fastest time in which the operation might be completed.

A business is launching a new product. The launch will require a number of related activities as follows – hire

a sales manager (5 weeks), require the sales manager to recruit sales people (4 weeks), train the sales people

(7 weeks), select an advertising agency (2 weeks), plan an advertising campaign with the agency (4 weeks),

conduct the advertising campaign (10 weeks), design the packaging of the product (4 weeks), set up packing

operation (12 weeks), pack enough products for the launch stock (8 weeks), order the launch quantity of

products from the manufacturer (13 weeks), select distributors for the product (9 weeks), take initial orders from

the distributors (3 weeks), dispatch the initial orders to the distributors (2 weeks). (a) What is the earliest time

that the new product can be introduced to the market? (b) If the company hire trained salesmen who do not

need further training, could the product be introduced 7 weeks earlier? (c) How long could one delay selecting

the advertising agency?

In the example above, if the sales manager cannot be hired for 3 weeks, how will that affect the total project?

In the previous example, if the whole project launch operation is to be completed as rapidly as possible, what

activities must have been completed by the end of week 16?

Identify a project of which you have been part (for example moving apartments, a holiday, dramatic production,

revision for an examination, etc.). (a) Who were the stakeholders in this project? (b) What was the overall project

objective (especially in terms of the relative importance of cost, quality and time)? (c) Were there any resource

constraints? (d) Looking back, how could you have managed the project better?

Identify your favourite sporting team (Manchester United, the Toulon rugby team, or if you are not a sporting

person, choose any team you have heard of). What kind of projects do you think they need to manage? For

example, merchandising, sponsorship, etc. What do you think are the key issues in making a success of

managing each of these different types of project?

6

5

4

3

2

1

Problems and applications

Table 16.6 Bespoke computer database activities

Activity Duration Activities that must

(weeks) be completed before

it can start

1 Contract negotiation 1 –

2 Discussions with main users 2 1

3 Review of current documentation 5 1

4 Review of current systems 6 2

5 Systems analysis (a) 4 3, 4

6 Systems analysis (b) 7 5

7 Programming 12 5

8 Testing (prelim) 2 7

9 Existing system review report 1 3, 4

10 System proposal report 2 5, 9

11 Documentation preparation 19 5, 8

12 Implementation 7 7, 11

13 System test 3 12

14 Debugging 4 12

15 Manual preparation 5 11

M16_SLAC0460_06_SE_C16.QXD 10/20/09 15:22 Page 493