Peden G.S. Arms, Economics and British Strategy From Dreadnoughts to Hydrogen Bombs

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

a Ministry of Supply in August 1939 to meet the army’s needs. A

Ministry of Aircraft Production followed in May 1940. Both ministries,

like the Ministry of Munitions in the First World War, recruited busi-

nessmen. However, there were other links between state and industry.

Edgerton estimates that perhaps half of all munitions were produced in

government-owned factories built since the 1930s , or with specialist

machines supplied by the government. Private firms acted as agents

managing governme nt factories, an arrangement that persisted into the

1960s. Shipyards were modernised during the war, largely at govern-

ment expense, with a remarkable extension of welding in place of riv-

eting being the most visible evidence of progress. Defence-related

research and development expanded, building upon the pre-war

experimental facilities of the defence departments and their links with

the arms industry and the universities. The pre-war military-industrial

complex had already developed Asdic and rad ar, and the number of

researchers employed or paid for by the stat e expan ded markedly after

1939. Scientists became established in Whitehall no less securely than

the better-known example of economists.

53

The input of science and technology could be crucial to the quality of

munitions, as the example of radar and other electronic aids showed in

weapons developed for air defence, strategic bombing or anti-submarine

warfare. Thus comparison of the effectiveness of war production in

different countries, or even as between different years, is far from easy,

and certainly not reducible to counting aircraft, guns or ships. After the

war German admirals complained that Germany had lagged behind

the Anglo-Saxon powers in the development of radar in the war at sea;

the same was generally true in the air war.

54

This Allied advantage

influenced the performance of aircraft and ships in ways not revealed by

the usual indicators of armament or speed.

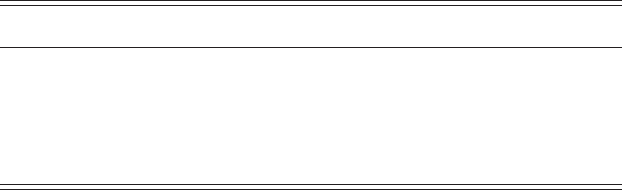

Even wh en one has apparently comparable statistics, as for aircraft

production, the totals have to be broken down, given the very different

requirements that Britain and Germany had for aircraft capable of co-

operating with the navy or army. Table 4.2 gives figures for output of

fighters and bombers, the two principal combat categories, and when

reading them one should remember that the relative cost of fighters and

bombers was roughly in the ratio 1:4. Britain overtook Germany in total

production in 1940, and in bomber production in 1941. Germany

overtook Britain in total production in 1944, on account of a huge surge

53

Edgerton, Warfare State , chs. 2–4. For shipyards, see Lewis Johnman and Hugh

Murphy, British Shipbuilding and the State since 1918: A Political Economy of Decline

(University of Exeter Press, 2002), esp. p. 82

54

Bennett and Bennett, Hitler’s Admirals, pp. 180–1; Overy, Air War, pp. 201–2.

The Second World War 185

in fighter production. Ge rmany had also produced more bombers than

Britain in 1943, but whereas 4,615 of the British ou tput had been heavy

bombers, only 261 Germa n machines came into this category, on

account of delays in developing the He 177.

55

The patterns of output

also reflected strategy: in Britain’s case, emphasis on defensive fighters

in 1940, but increasing emphasis on bombers for the air offensive

against Germany; in Germany’s case, increasing emphasis on fighter

production in response to the Allied air offensive. Output, and the

industrial investment necessary to achieve it, could also reinforce

strategy. When the question arose of whether the strategic air offensive

should continue, given that resources might be better employed in

preparing for a second front, the Air Staff was able to point out in

February 1942 that the aircraft industry was committed to the pro-

duction of heavy bombers, and that a change of policy would disrupt

output and reduce pressure on Germany.

56

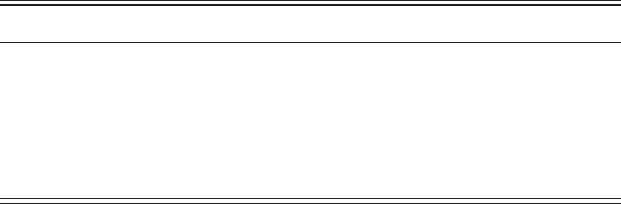

The statistics for tank output seem to show Britain lagging behi nd

Germany (table 4.3). However, British production was on the basis of

supplying 55 divisions, including those of the dominions and allies, and

most of these units were only being formed in 1939–40. Germany used

136 divisions against France and the Low Countries in May 1940; by

Table 4.2. British and German aircraft production, 1939–44

Total Fighters Bombers

Britain

1939 7,940 1,324 1,837

1940 15,049 4,283 3,488

1941 20,094 7,064 4,668

1942 23,672 9,849 6,253

1943 26,263 10,727 7,728

1944 26,461 10,730 7,903

Germany

1939 8,295 1,856 2,877

1940 10,826 3,106 3,997

1941 11,776 3,732 4,350

1942 15,556 5,213 6,539

1943 25,527 11,738 8,589

1944 39,807 28,926 6,468

Sources: Postan, British War Production, pp. 484–5; Webster and Frankland,

Strategic Air Offensive, vol. IV, pp. 494–5.

55

Postan, British War Production, p. 485; Green, Warplanes of the Third Reich, p. 343.

56

Webster and Frankland, Strategic Air Offensive, vol. I, p. 330.

Arms, economics and British strategy186

1941 the German army had a total of 208 divis ions, of which 167 were

full strength.

57

Very roughly, one would expect German output of tanks

to be three times British output, if the German army were to be as

mechanised as the British, but this ratio occurred only in 1944. Indeed,

from 1941 to 1943 the total number of tanks supplied to the British army

from American and United Kingdom sources exce eded total German

production. Whatever may have been the problems with the quality of

tanks available to the British army, there was no lack of quantity.

The issue of quality is one of the themes of Barnett’s controversial

study of Britain’s war-time industrial performance, The Audit of War,in

which he compares Britain very unfavourably with Germany and the

United States in the design, development and production of tanks and

aircraft.

58

As the review of weapons in previous sections shows, there

were serious problems of quality with British tanks, and most of Bar-

nett’s criticisms are justified, although he underestimates the problems

faced by companies that were expected by the War Office and the

Ministry of Supply to be able to switch from manufacturing motor

vehicles or steam locomotives to designing and developing armoured

fighting vehicles. The successful design of the Cromwell and Comet

tanks, by the Birmingham Railway Carriage and Wagon Company and

Leyland Motors Ltd respectively, in the latter part of the war suggests

Table 4.3. Production of tanks and self-propelled artillery on tank chassis, 1939–44

UK production Supplied from overseas

a

Germany

1939 969 0 1,300

1940 1,399 0 2,200

1941 4,841 1,390 5,200

1942 8,611 9,253 9,200

1943 7,476 15,933 17,000

1944 5,000 6,670

b

22,100

Notes:

a

Almost entirely from United States, as most Canadian production was retained in

Canada for training or shipped to the Soviet Union.

b

First six months only. Part of British allocation from production in the United States was

diverted to the American army in the latter part of year – H. Duncan Hall, North American

Supply (London: HMSO, 1955), p. 416.

Sources: Central Statistical Office, Statistical Digest of the War, p. 148, for British figures,

including overseas supplies; Overy, Why the Allies Won, p. 322, for German figures.

57

R. A. C. Parker, Struggle for Survival: The History of the Second World War (Oxford

University Press, 1989), pp. 28, 67.

58

Barnett, Audit of War, pp. 143–58, 161–4.

The Second World War 187

movement along a learning curve. Production of the Cromwell provided

a striking example of oppor tunity cost wh en allocating plant and labour.

The Cromwell Mark III used a 600 h.p. Meteor aero-type engine and

output was governed by the number that the Ministry of Aircraft Pro-

duction was willing to make available to the Ministry of Supply. Con-

sequently, Liberty engines of 375 h.p., which happened to be available,

were used for a Mark II Cromwell that was slower than the Mark III.

59

In the case of aircraft, Barnett makes the British performance seem

worse than it was by using selective comparisons. For example, he lists

six unsuccessful British types of aircraft: the Sabre-powered Hawker

Typhoon and Tempest, and the Westland Welkin fighter, the Bristol

Buckingham medium bom ber and the Vickers Windsor and Warwick

heavy bombers. On the other hand, he mentions only two German

failures, the Heinkel He 177 heavy bomber and the Junkers Ju 288

medium bomber, without commenting on the fact that the failure of the

Heinkel machine deprived Germany of the means of conducting stra-

tegic bombing.

60

There were other unsuccessful German designs.

Focke-Wulf attempted to develop an all-wood fighter, the Ta 154, with

a view to conserving steel and light alloys, and as an answer to the

British Mosquito; however, production had to be abandoned, owing to

problems in procuring suitable wood glue and in arranging satisfactory

sub-contracting of wooden components.

61

Other spectacular failures

included Messerschmitt’s attempt to develop a replacement for its Bf

110 twin-engined fighter, the Me 210, which was abandoned on

account of its poor flying characteristics after 554 had been completed

or were in various stages of construction, and the Me 410, production of

which was ended within two years of it entering service on account of its

vulnerability to American fighters. The Arado Ar 240, which was to

have had night-fighter, high-speed bomber and reconnaissance versions,

was abandoned because of its flying characteristics and teething pro-

blems after a handful of the reconnaissance version had been produced.

The Heinkel He 162, which Barnett describes as one of the first jet

aircraft in service, was issued to squadrons in 1945 but pilots were

instructed to avoid combat pending completion of trials and it never saw

59

Lord Weir to Minister of Supply, n.d. but autumn 1942, Weir Papers 21/2, Churchill

College, Cambridge.

60

Barnett, Audit of War, p. 147. For the problems with the British aircraft mentioned, see

Postan, Hay and Scott, Design and Development, pp. 126–32, who point out that the

Welkin was not a complete failure (it did not go into service because the threat it was

intended to meet, sub-stratosphere bomber attacks, did not materialise), and the

Buckingham was similar in performance to its American contemporary, the Douglas

Invader, and suffered in comparison with its British contemporary, the Mosquito.

61

Green, Warplanes of the Third Reich, pp. 241–5.

Arms, economics and British strategy188

action.

62

It is in the nature of developing advanced aircraft that not all

will succeed, and on balance the British aircraft industry does not seem

to have been more prone to failure than the German.

Sir Alec Cairncross, having compared the British and German aircraft

industries, concluded that German firms had more skilled staff and

superior development facilities, but the planning of aircraft production

was certainly no better in Germany and in some respects, for example

gaps in production runs, a good deal worse. The British practice of

continuing production of obsolescent types was not entirely wasteful,

since use could be made of them as glider-tugs or trainers, for example.

Neither Britain nor Germany, Cairncross thought, could compare with

the United States as regards boldness in planning, speed of execution, or

productivity.

63

Edgerton has pointed out that the American aircraft

industry’s superior productivity reflected longer production runs and

that, while German productivity was higher than British in 1944, when

the Germa ns had concentrated production on a limited range of aircraft,

the reverse was almost certainly the case earlier in the war, when British

output exceeded German output. Studies of the Luftwaffe have con-

cluded that from the 1930s, and for much of the war, the Germans

made sub-optimal use of their resources for aircraft production by

failing to achieve a rational allocation of work to design teams, by setting

unnecessarily high standards for manufacturing minor fittings, and by

wasteful use of raw materials, especially aluminium.

64

The scale of British war production was related to strategy. From

September 1939 to May 1940 some industrial capacity was reserve d for

exports to help to pay for essential imports in a three-year war. In May

1940 the danger of defeat was so pressing that Beaverbrook, the minister

of aircraft production, claimed absolute priority over other calls on

industry. In 1941 the shortage of tanks and anti-tank guns in the

Western Desert became almost as much an emergency requirement as

aircraft had been the year before, and Beaverbrook, transferred to the

Ministry of Supply, once more tried to maximise production. Unfor-

tunately, his reliance on hustle rather than planning, however appro-

priate for running a newspaper like the Daily Express, which he owned,

could be disruptive when it came to supplying the needs of the air force

62

Ibid., pp. 58–62, 366–73, 610–14, 658–63.

63

Alec Cairncross, Planning in Wartime: Aircraft Production in Britain, Germany and the

USA (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1991).

64

Edgerton, ‘Prophet militant’, Twentieth Century British History, 2 (1991), 373–4;

Edward L. Homze, Arming the Luftwaffe: The Reich Air Ministry and the German Aircraft

Industry 1919–39 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1976), pp. 189–91, 212–16,

261–7; Williamson Murray, Luftwaffe (London: Allen and Unwin, 1985), pp. 93–9,

128–9.

The Second World War 189

and army. Targets set for aircraft production were too ambitious and

had to be scaled down; improvisation replaced organisation, and the

aircraft industry ceased to pay attention to instructions from the min-

istry, proceeding on the basis of doing the best they could, like self-

employed tradesmen. It was not until after Beaverbrook had left the

Ministry of Aircraft Production in May 1941 that planning could ensure

that there was consistency in programmes for aircraft and components.

Production did rise in 1940, but it was rising before Beaverbrook took

over, and during 1941 bottlenecks sprang up, mainly on account of

maldistribution of components and materials.

65

As for tank production,

no amount of hustle could produce a quick solution to the problems of

poor design and inexperienced manufacturers.

From March 1941, with the passing of the Lend-Lease Act, British

war production could take increasing account of what could be better

supplied from the United States. The falling off in British tank pro-

duction after 1942 reflected the fact that it was no longer necessary for

Britain to be self-sufficient; on the other hand, continued British pro-

duction was a necessary insurance against a shortfall in American

deliveries. Likewise the fact that British steel production peaked in 1942

and declined by 9.8 per cent by 1944 reflected the shipping shortage,

which made it more sensible to import finished steel from the United

States than to import more bulky iron ore.

66

As in the First World War, the key factor of production was labour.

The introduction of conscription in April 1939 made it possible to

register all workers and to prevent skilled labour and other reserved

categories of men being recruited by the services, in contrast to what had

happened in 1914–1 5. A ceiling of about 2 million was placed on the

size of the army in 1941, to ensure that it did not drain manpower from

munitions production. Under the Emergency Powers (Defence) Act of

22 May 1940, the minister of labour and national service could direct

any person in the United Kingdom to perform any work in any place,

and, although Bevin used his powers with moderation, labour was

transferred to munitions work from firms producing consumer goods.

From 1941 the Board of Trade had powers to close factories so as to

concentrate production of the reduced volume of consumer goods in

fewer firms and to release more labour for munitions work. To prevent

munitions produc tion being disrupted, Bevin took powers in July 1940

to refer disputes causing strikes or lockouts to compulsory arbitration.

65

Cairncross, Planning in Wartime, pp. 7–8, 12–13; Postan, British War Production,

pp. 116, 118, 124, 137–8; Ritchie, Industry and Air Power, pp. 229–30, 234–8.

66

Central Statistical Office, Statistical Digest of the War (London: HMSO, 1951), p. 107.

Arms, economics and British strategy190

To prevent disruption from poaching or turnover of labour, no work er

could leave or be dismissed from any factory scheduled by the Ministry

of Labour and National Service without the minister’s consent after

March 1941. Conscription of labour was introduced gradually by age,

skill and gender, with conscripti on of women being delayed until the

end of 1941, when Bevin felt that public opinion was ready for a m ea-

sure that even Hitler did not impose on Germans.

These powers made it possible to allocate labour according to the

needs of strategy. In May 1940 aircraft production was given the highest

priority for new war workers, but this made for shortages in other pro-

grammes, besides reducing pres sure on aircr aft firms to adopt dilution.

Consequently at the end of September 1940 the War Cabinet decided

that labour must be allocated in proportion to all approved programmes.

Manpower budgeting, toget her with allocation of materials and indus-

trial capacity became the basis of planning the war economy.

67

How-

ever, manpower budgeting was not an exact science. The labour

required to meet the services’ requirements had to be estimated on the

basis of past experience of production, tempered by the knowledge that

man-hours employed in making, say, an aircraft would fall as firms

moved along a learning curve in its production; and by a known ten-

dency of firms and departments to overstate their needs. The final

outcome of the manpo wer budget was decided by the Prime Min ister,

and therefore reflected his view of strategic priorities.

68

It was one thing to mobilise labour; quite another thing to ensure that

it was used efficiently. Dilution, especially in engineering and ship-

building, raised endless problems. Barnett, with some justifi cation, is

highly critical of the shipbuilding industry’s reluctance to accept changes

necessary to increase productivity even in the worst days of the Battle of

the Atlantic.

69

The industry had responded to the inter-war depression

by closing surplus capacity, but with only a very small rise in pro-

ductivity in yards that remained open; indeed, output per man in the

late 1930s was very little, if at all, above wh at it had been before the First

World War.

70

Bevin’s negotiations with the shipyard unions to secure

the optimum use of scarce skilled labour during the war ran up against

distrust that dilution would lower wages and create unemployment once

67

Bullock, Life and Times of Ernest Bevin, vol. II, chs. 1–6; Hancock and Gowing, British

War Economy, chs. 11 and 15; P. Inman, Labour in the Munitions Industries (London:

HMSO, 1957), chs. 7–8.

68

Wilson, Churchill and the Prof, pp. 104–11.

69

Barnett, Audit of War, ch. 6.

70

J. R. Parkinson, ‘Shipbuilding’, in Neil Buxton and Derek Aldcroft (eds.), British

Industry between the Wars: Instability and Industrial Development 1919–1939 (London:

Scolar Press, 1979), pp. 79–102, at p. 87.

The Second World War 191

peace returned. Even when he had the support of a national trade union,

he might be defied by its membe rs at shipyard le vel. For example, the

fitters at Newport, in South Wales, insisted throughout the war on

working in pairs, as was their custom, although in every othe r yard in the

country a fitter would work with a semi-skilled mate.

71

Matters were

worse in coal-mining, where output actually fell during the war, partly

on account of miners being allowed to move out of the industry in 1940,

when export markets in Western Europe were lost, but also because of

the inheritance from the inter-war depression of an ageing and dis-

affected workforce.

72

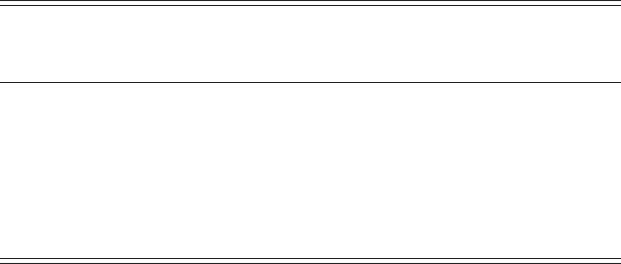

Coal lost more days of work on account of strikes

than any other industry. In industry as a whole strikes were more fre-

quent than they had been in the First World War, but they tended to be

resolved quickly, so that the average annual loss of working days in

1939–45 was about half that of 1914–18. As in the First World War,

industrial relations deteriorated the longer the war went on (see table

4.4); hence a series of white papers in 1944 aimed at maintaining morale

by promises of universal social insurance, a national health service, and

high and stable employment after the war.

73

One group of producers who fared well during the war were farmers,

whose share of national income rose from 1.2 per cent in 1938–9 to 2.4 per

cent in 1944–5. Agriculture had been depressed before the war and the

rapid increase in farmers’ incomes helped to finance the increase in output

necessary if the government’s target of a 25 per cent reduction in food

imports was to be achieved. In fact the eventual reduction was 55 per cent.

Table 4.4. Numbers of days lost in strikes and lockouts in all industries and services, and the

percentage of these that were in coal-mining, 1914–18 and 1939–45

(’000) (%) (’000) (%)

1914 9,878 37.6 1939 1,356 41.7

1915 2,953 55.6 1940 940 53.7

1916 2,446 12.7 1941 1,079 31.0

1917 5,647 20.7 1942 1,527 55.0

1918 5,875 19.8 1943 1,808 49.2

1944 3,714 66.8

1945 2,835 22.6

Source: Source: Department of Employment and Productivity, British Labour Statistics:

Historical Abstract 1886–1968 (London: HMSO, 1971), p. 396.

71

Bullock, Life and Times of Ernest Bevin, vol. II, pp. 61–2.

72

W. H. B. Court, Coal (London: HMSO, 1951).

73

Paul Addison, The Road to 1945: British Politics and the Second World War (London:

Jonathan Cape, 1975), pp. 215–25, 240–8.

Arms, economics and British strategy192

To save shipping space, the Ministry of Agriculture directed farmers to

concentrate on the production of grain, and guaranteed markets and

prices. Agriculture showed that the profit motive and state direction could

be successfully combined to create a more efficient sector.

74

On the other hand, it was realised that profits in industry might

undermine support for the war effort from trade unions or the wider

public. The September 1939 budget introduced an excess profits tax

(EPT) levied at 60 per cent of profits in excess of a standard based on

pre-1938 profits. The Treasury was aware that raising EPT to 100 per

cent would remove all financial incentive from businessmen to make

more efficient use of resources or to take risks with new investment,

since any profit arising from reducing costs would be taken away.

Nevertheless, it was necessary to offset the Emergency Powers

(Defence) Act of May 1940, with its controls over labour, with a

declaration that there would be no profit from the national emergency,

and EPT was raised to 100 per cent. The 1941 budget restored some

incentive to make more efficient use of capital by promising that 20 per

cent of EPT paid during the war would be repaid afterwards, provided

that the refund was ploughed back into a business.

75

Even so, there was

a strong incentive for businessmen to negotiate contracts that would

cover their costs plus a standard profit, and to be content with managing

government factories rather than take risks. Cost-plus was not a good

basis for increasing productivity of labour or plant, making it all the

more important to try to increase productivity through contract proce-

dures that allowed for technical costing by government agents. The view

of the official historian of contracts and finance is that the system

worked in war-time.

76

However, a cost-plus mentality may have taken

root in firms in the aircraft and other industries that would make them

less competitive in peace.

As in the First World War, the Treasury saw the purpose of war

finance as the adjustment of production and consumption so as to

maintain essential supplies for the civil population, while securing the

largest possible proportion of national income for the government. In

1939 the Treasury thought that at least one-half of national income

should be made available for government needs.

77

Table 4.5 shows that

74

Keith A. H. Murray, Agriculture (London: HMSO, 1955), pp. 241, 290, 340, 374–5,

378–9.

75

Peden, Treasury and British Public Policy, pp. 319, 321, 324.

76

William Ashworth, Contracts and Finance (London: HMSO, 1953), esp. p. 242.

77

Sir Richard Hopkins, ‘Draft statement on war finance for the National Joint Advisory

Council on 6th December 1939’, T 175/117, TNA.

The Second World War 193

this target was achieved, partly by a drastic reduction in the consumer’s

share of output, and partly by dis investment: firms’ depreciation funds

were diverted to government loans; plant for civilian use was no t

replaced; and railways and roads were allowed to deteriorate. However,

whereas most of the reduction in the consumer’s share of output in the

First World War had been brought about by inflation caused by gov-

ernment borrowing (and inflation had fuelled industrial discontent over

wages, causing strikes and disrupting production), financial policy in the

Second World War reduced inflation to a minimum. High taxes on

income reduced consumers’ spending power, while price controls and

rationing ensured that essential goods remained affordable and available.

‘Luxuries’, including alcohol and tobacco, which had little or no weight

in the Edwardian working-class cost-of-living index that was still in use,

were taxed heavily to reduce the spending power of people not affected

by income tax. Keynes used national income analysis to advise the

chancellor on how much should be raised from taxation and savings.

However, the disincentive effe ct of high rates meant that incom e tax

could not be raised further after the 1941 budget, when the standard rate

reached 10s (50p) and the top marginal rate of income tax plus surtax,

paid by the very rich, was 19s 6d (97.5p). The introducti on of pay-

as-you-earn (PAYE) made it possible to tax working-class wage-earners

in a way that had not been possible in the First World War, and the policy

of stabilising the cost-of-living index encouraged some moderation on

the part of trade unions in their demands for higher wages.

78

Table 4.5. Percentage shares of national income (NNP), 1938–45

Government

military

expenditure

Government

civil

expenditure

Consumer

expenditure

Net non-war

capital

formation

1938 7 10 78 5

1939 15 9.5 73.5 2

1940 44 8 64 16

1941 54 7 56 17

1942 52 8 52 12

1943 56 7 49 12

1944 54 7 51 12

1945 49 7 54 10

Source: Sidney Pollard, The Development of the British Economy 1914–1990 (London:

Edward Arnold, 1992), p. 174. ª Edward Arnold (Publishers) Ltd.

78

Peden, Treasury and British Public Policy, pp. 320–7.

Arms, economics and British strategy194