Perrie M. (ed.) The Cambridge History of Russia, Volume 1: From Early Rus’ to 1689

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

jonathan shepard

served as a kind of victory monument to Vladimir’s role in the conversion of

his people.

The middle Dnieper is the region where Rus’ churchmen’s rhetoric con-

cerning ‘new Christian people, the elect of God’ rings most true. In order

to protect his cult centre, Vladimir established new settlements far into the

steppe, taking advantage of the black earth’s fertility. Kievitself was enlarged to

enclose some 10 hectares within a formidable earthen rampart and ramparts

of similar technique were raised to the south of the town. The construction of

barriers and strongholds along the main tributaries of the Dnieper brought a

new edge to Rus’ relations with the nomads. Although never unproblematic,

these had hitherto involved constant trading and had more often than not

been peaceable. There was now, according to the Primary Chronicle, ‘great and

unremitting strife’

34

and although Kiev was secure, even the largest of the for-

tified towns shielding it came under pressure from the Pechenegs. Belgorod,

south-west of Kiev, underwent a prolonged siege. It did not, however, fall and

this owed something to the layers of unfired bricks forming the core of the

ramparts, which still stand between five and six metres high. They enclosed

some 105 hectares, and a very high level of organisation was needed to supply

the inhabitants. The princely authorities adapted techniques from the Byzan-

tine world, not only brick- and glass-making but also plans for large cisterns

and a beacon system perhaps fuelled by naphtha. Few new towns matched

Belgorod or Pereiaslavl’ in size and many settlements lacked ramparts, the

nearbyforts serving as places of refuge. But the grain and other produce grown

by the farmers fed the cavalrymen and horses stationed in the forts, sickles

and ploughshares were manufactured in the smithies, and nexuses of trade

burgeoned. Finds of glazed tableware and, in substantial quantities, amphorae

and glass bracelets attest the prosperity of the settlements’ defenders. The

risks of voyages to Byzantium were mitigated – though never dispelled –

by ramparts beside the Dnieper and a large fortified harbour near the River

Sula’s confluence with the Dnieper, at Voin. Cavalry could escort boats to the

Rapids, and from the late tenth century the Byzantine government let the Rus’

establish a trading settlement in the Dnieper estuary.

The middle Dnieper region had not been densely populated before

Vladimir’s reign. He is represented by the Primary Chronicle as rounding up

‘the best men’ from among the Slav and Finnish inhabitants of the forest

zone and installing them in his settlements.

35

The newcomers to the hundred

34 PVL,p.56.

35 PVL,p.54.

68

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The origins of Rus’ (c.900–1015)

or more forts and settlements in the great arc protecting Kiev were prime

targets for evangelisers, as well as raiders. Divine intervention supporting

princely leadership was in constant demand, and one of the few bishoprics

quite firmly attributable to Vladimir’s reign is that of Belgorod. At Vasil’ev

Vladimir founded a church and held a great feast in thanksgiving, after hiding

under its bridge from pursuing Pechenegs. The apparent intensity of pastoral

care and the deracination of most of the population from northern habitats

made inculcation of Christian observances the more effective. Judging by the

funerary rituals in the burial grounds of these settlements, few flagrantly

pagan practices persisted. Barrows were not heaped over graves in cemeter-

ies within a 250-kilometre radius of Kiev, or in regions such as the Cherven

towns where Christianity was already well established. Elsewhere barrows

were much more common, although heaped over plain Christian burials.

The small circular barrows often contained pottery, ashes and food symbol-

ising – if not left over from – funeral feasts, occasions of which the Church

disapproved.

The regions and key points where Vladimir’s conversion transformed the

landscape, physically as well as figuratively, were finite but the number of per-

sons affected was considerable. New Christian communities were instituted

in the middle Dnieper region and existing ones in the trading network mas-

sively reinforced, especially in the northern towns frequented by Christians

from the Scandinavian world. Novgorod was made an episcopal see. Churches

were most probablybuiltand priests appointed in Smolensk and Polotsk,albeit

without resident bishops. Even in north-eastern outposts, Christianity became

the cult of retainers and other princely agents, and it appealed to locals traf-

ficking with them and aspiring to raise their own status. At Uglich on the

upper Volga (as at Smolensk, Pskov and Kiev itself ) the pagan burial grounds

were destroyed in the wake of Vladimir’s conversion and in the first quarter of

the eleventh century a church dedicated to Christ the Saviour was built. Soon

members of the elite began to fill St Saviour’s graveyard in strict accordance

with Church canons. Vladimir’s tribute collectors and other itinerant agents

did not just owe allegiance in return for treasure such as his new-fangled sil-

ver coins, share-outs of tribute and sumptuous feasts featuring silver spoons,

important as these were (for examples of Vladimir’s silver coins, see Plate 2).

They had religious affiliations with him: greed, ambition and concern for indi-

vidual survival in life and after death fused with loyalty to the prince. Vladimir

probably saw the advantages of instilling the faith into the next generation.

There is no particular reason to doubt that the children of ‘notable families’

69

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

jonathan shepard

were taken off to be instructed in ‘book learning’ while their mothers, ‘still

not strong in the faith...weptforthem as if they were dead’.

36

The wording of the Primary Chronicle seems to treat book learning as more

or less synonymous with studying the Scriptures and the new religion, and

Vladimir stood to gain moral stature from enlightening his notables’ children.

One should not, however, suppose that the literacy which boys – maybe also

girls – of his elite obtained was of much application to everyday governance.

The administrative and ideological underpinnings of princely rule were still

quite rudimentary, even if Vladimir loved his ‘retainers and consulted them

about the ordering of the land, about wars and about the law of the land’.

37

The ‘land of Rus” was an archipelago of largely self-regulating communities.

Extensive groupings in the north were still considered tribes, most notoriously

the Viatichi. It was mainly in Vladimir’s new fortresses and settlements in

the middle Dnieper region that princely commanders, town governors and

agents were numerous enough to intervene in the affairs of ordinary people;

the standing alert against the nomads required as much. But even there the

officials seem to have had little occasion to issue deeds or written judgements.

Nordo theyseem tohave playeda commanding role inadjudicating disputes or

enforcinglaws.Therehad long beensome sense of duelegalprocess among the

Rus’. Procedures for making amends for insults, injuries, thefts and killings

inform the tenth-century treaties with the Byzantines. However, practical

measures for conflict resolution of mutually inimical parties fell far short of

upholding an inherently ethical code, of punishing upon Christian principle

actions deemed sinful. A hint of attitudes towards justice as a non-negotiable

quality is offered by a passage in the Primary Chronicle, perhaps first set down

before Vladimir’s reign passed from living memory. Vladimir’s bishops urged

punitive action against robbers, for ‘you have been appointed by God to punish

evil-doers’. Vladimir gave up exacting fines in compensation for offences (viry)

but later he reverted to ‘the ways of his father and grandfather’.

38

The story

shows awareness in Church circles that Rus”s ‘new Constantine’

39

had only

limited conceptions concerning his authority.

Vladimir’s regime rested less on elaborate institutional frameworks or jus-

tifications in law than on well-oiled patronage mechanisms and the aura with

whichhispaternal ancestryinvestedhim.Thebloodof a murderedhalf-brother

on one’s hands could be offset by imposing a well-ordered public cult. In every

36 PVL,p.53.

37 PVL,p.56.

38 PVL,p.56.

39 PVL,p.58.

70

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The origins of Rus’ (c.900–1015)

other way, family blood and concomitant bonds were assets that Vladimir

exploited to the full. His maternal uncle, Dobrynia, seems to have been a

mainstay and there is no sign of the multiplicity of ‘princes’ or magnates

attested for the middle Dnieper in the mid-tenth century. The losses incurred

during Sviatoslav’s campaigns and his sons’ internecine strife may have cleared

what was always a hazardous deck. In any case, Vladimir quite soon came to

rely on his own sons in what was probably a new variant of collective, fam-

ily, leadership. He was not the first Rus’ prince to assign sons to distant seats

of authority, but he seems to have carried this out on a wider scale than his

predecessors. Twelve sons are named and associated with seats by the Primary

Chronicle, a likely evocation of the twelve Apostles. The actual number of sons

assigned to towns may well have been greater, since the distinction between

those born in wedlock rather than to a concubine was not sharply drawn. That

Vladimir was the father was what mattered: they could deputise for him in

a variety of places. If it is unsurprising that a son was installed in Novgorod,

the failure to grace Pskov – the town of Vladimir’s grandmother and proba-

bly a longstanding seat of authority – with a prince of its own is noteworthy.

So is the assignment of sons to towns which, though of fairly recent origin,

had proved to be potential power bases, Polotsk and Turov. When Iziaslav,

Vladimir’s first assignee to Polotsk, died in 1001, his son was permitted to take

his place and, in effect, put down the roots of a hereditary branch of princes

there;Iziaslav’smother had been Rogneda,daughter of Rogvolod. Presumably

Vladimir calculated that so strongly rooted a regime would block any future

bids for Polotsk by outsiders. Princes were also sent to locales whose ties with

the urban network had not been specifically ‘political’. For example, Rostov

was only developed into a large town in the 980sor990s, when the local inhabi-

tants were mainly the Finnic Mer. The newly fortified town was dignified with

a resident prince, Iaroslav, and an oaken church was subsequently built. Some

places of strategic importance but lacking recent princely associations were

not assigned a prince. It was a governor who had to cope with Viking-type

raids on Staraia Ladoga and the town suffered conflagrations, at the hands of

Erik Haakonson in 997 and of Sveinn Haakonson early in 1015.

Sveinn raided down ‘the East Way’ at a time when the shortcomings of

Vladimir’s regime were becoming plain. Ties between father and sons could

hold together for a generation of peace, but they were not immune from jock-

eying for prominence and ultimate succession. By around 1013 Vladimir’s rela-

tions with one leading son, Sviatopolk, were so fraught that he was removed

from his seat in Turov and imprisoned. And, ominously, Vladimir’s relations

with the occupant of the most important seat after Kiev itself deteriorated

71

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

jonathan shepard

drastically. In 1014 Iaroslav, now prince of Novgorod, held back the annual

payment due from that city to Kiev and Vladimir began detailed preparations

for the march north. The fact that Vladimir was on such bad terms with two

of his foremost sons suggests that thoughts about the succession were in the

air. Iaroslav ‘sent overseas and brought over Varangians’ for what promised to

be outright war.

40

However, Vladimir fell ill, putting off the expedition, and

on 15 July 1015 he died.

Essentially, the vast ‘land of Rus” was a family unit, with all the affinities

and tensions germane to that term, and there were no effective ritual or legal

mechanisms making for a generally accepted succession. Once the family

‘patriarch’ died, these uncertainties could only be resolved by a virtual free-

for-all between the more or less eligible sons of Vladimir. The coming of

Christianity fostered economic well-being, fuller settlement of the Black Earth

region and cultural advance, while a kind of ‘cult of personality’ now invested

Vladimir, accentuating the aura of princely blood. Over the centuries there

would scarcely ever be a question of persons who were not his descendants

seizing thrones for themselves in Rus’. This was partly due to force of custom

and princely retinues’ force majeure. But there was also symbiosis amounting

to consensus across diverse populations and urban centres with a positive

interest in the status quo – and in the profits to be had from long-distance

trading. For these members of Rus’, the tale of the summoning of Riurik from

overseas had resonance. The regime fashioned by Vladimir could maintain

order of a sort. There was no other overriding authority, no well-connected

senior churchmen to knock princely heads together. But given the remarkable

make-up of Christian Rus’, how could it have been otherwise?

40 PVL,p.58.

72

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

4

Kievan Rus’ (1015–1125)

simon franklin

The period from 1015 to 1125, from the death of Vladimir Sviatoslavich to

the death of his great-grandson Vladimir Vsevolodovich (known as Vladimir

Monomakh), has long been regarded as the Golden Age of early Rus’: as an age

of relatively coherent political authority exercised by the prince of Kiev over

a relatively coherent and unified land enjoying relatively unbroken economic

prosperity and military security along with the first and best flowerings of a

new native Christian culture.

1

One reason for the power of the impression lies in the nature of the native

sources. This is the age in which early Rus’, so to speak, comes out from under

ground, whenarchaeological sources are supplemented by native writings and

buildingsandpictureswhichsurvivetothepresent.Fromthemid-eleventh cen-

tury onwards, in particular, the droplets of sources begin to turn into a steady

trickle and then into a flow. Before c.1045 we possess no clearly native narrative,

exegeticor administrative documents. By 1125 wehavethe first sermons,saints’

lives, law codes, epistles and pilgrim accounts, as well as a rapidly increasing

quantity of brief letters on birch bark and of scratched graffiti on church walls

and miscellaneous objects.

2

Before the death of Vladimir Sviatoslavich no

component of our main narrative source, the Primary Chronicle (Povest’ vre-

mennykh let) is clearly derived from contemporary Rus’ witness; by the early

twelfth century, when the chronicle was compiled, its authors could incorpo-

rate several decades of contemporary native narratives and interpretations.

No building from the age of Vladimir Sviatoslavich or earlier survived above

ground into the modern age. Monumental buildings from the mid-eleventh

1 On this as the ‘Golden Age’ see e.g. Boris Rybakov, Kievan Rus (Moscow: Progress Pub-

lishers, 1984), pp. 153–241. Other general accounts of the period: George Vernadsky, Kievan

Russia,7th printing (NewHavenand London: Yale University Press,1972); Simon Franklin

and Jonathan Shepard, The Emergence of Rus 750–1200 (London and New York: Longman,

1996), pp. 183–277.

2 On written sources see Simon Franklin, Writing, Society and Culture in Early Rus c.900–1300

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002).

73

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

simon franklin

to early twelfthcenturies can still be seen today – in varying states of complete-

ness – the length of Rus’, from Novgorod in the north to Kiev and Chernigov in

the south. Still more survived until the mid-twentieth century, when theywere

destroyed either by German invaders or by Stalinist zealots.

3

These early writ-

ings and buildings came to acquire – and in some cases were clearly intended

to convey – an aura of authority, a kind of definitive status as cultural and

political and ideological models, as the foundations of a tradition.

Between1015 and 1125, then, forsubsequent observersRus’emerged into the

light, and immediately contemplated and celebrated its own enlightenment.

Such perceptions are real and significant facts of cultural history. However,

their documentary accuracy is debatable and our own retelling of the period

is necessarily somewhat grubbier than the image.

Dynastic politics

Political legitimacy in Rus’ resided in the dynasty. The ruling family managed

to create an ideological framework for its own pre-eminence which was main-

tained without serious challenge for over half a millennium. To this extent

the political structure was simple: the lands of the Rus’ were, more or less

by definition, the lands claimed or controlled by the descendants of Vladimir

Sviatoslavich (or, in more distant genealogical legend, by the descendants of

the ninth-century Varangian Riurik). But the simplicity of such a formulation

hides its potential complexity in practice. It is one thing to say that legiti-

macy resided in the dynasty, quite another to determine how power should be

defined and allocated within it. Legitimacy was vested in the family as a whole,

not in any individual member of it. Power was distributed and redistributed,

claimed and counter-claimed, among members of a continually expanding

kinship group, not passed intact and by automatic right from father to son.

The political history of the period thus reflects, above all, the interplay of two

factors, the dynastic and the regional: on the one hand the issue of precedence

or seniority within the ruling family; on the other hand – as a consequence of

the distribution of power – the increasingly entrenched and often conflicting

regional interests of its local branches.

The changing patterns of internal politics are most graphically shown at

moments of strain resulting from disputes over succession. Succession took

place both ‘vertically’ from an older generation to a younger, and ‘laterally’

3 See e.g. WilliamCraft Brumfield, A History of Russian Architecture (Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 1993), pp. 9–33.

74

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Kievan Rus’ (1015–1125)

betweenmembersof thesamegeneration,frombrothertobrother orcousinto

cousin. Three times between1015 and 1125 the dynasty had to adjust to ‘vertical’

succession: in 1015 on the death of Vladimir himself; in 1054 on the death of his

son Iaroslav, and in 1093 on the death of his grandson Vsevolod (see Table 4.1).

On each occasion the adjustment to ‘vertical’ succession introduced a fresh set

of ‘lateral’ problems among potential successors in the next generation, and

on each occasion the solutions were slightly different. Through looking at the

sequenceof adjustments to changesofpowerwecan follow the development of

a set of conventions and principles which, though never neat or fully consistent

in their application, are the closest we get to a political ‘system’.

4

In1015 Vladimir’ssons werescatteredaround the extremitiesof the lands, for

it had been his policy to consolidate family control over the tribute-gathering

areas by allocating each of his sons to a regional base. One was given Turov,

to the west, on the route to Poland; another had the land of the Derevlians,

the immediate north-western neighbours of the Kievan Polianians; one was

installed at Novgorod in the north, another at the remote southern outpost of

Tmutorokan’, beyond the steppes, overlooking the Straits of Kerch between

the Black Sea and the Azov Sea. There were a couple of postings in the north-

east, at Rostov and Murom, and one in Polotsk in the north-west. This was

Vladimir’s framework for ensuring that each of his sons had autonomous

means of support and that the family as a whole could establish and maintain

the territorial extent of its dominance.

On Vladimir’s death this structure collapsed. Despite their remoteness from

each other, the regional allocations were clearly not regarded as substitutes

for central power (if we regard the middle Dnieper region as the ‘centre’). The

only exception was Polotsk, where Vladimir’s son Iziaslav had already died

and had been succeeded by his own son Briacheslav: there is no indication that

Briacheslav competed with his uncles,and this is the first recorded example of a

regional allocation coming to be treated as the distinct patrimony of a particu-

lar branch of the family. RelationsbetweenVladimir’s survivingsons, however,

were more turbulent. Three were murdered (two of them, Boris and Gleb,

wenton to become venerated as saints),

5

and three more – Sviatopolk of Turov,

4 On the political conventions of the dynasty see Nancy Shields Kollmann, ‘Collateral

Succession in Kievan Rus”, HUS 14 (1990): 377–87; Janet Martin, Medieval Russia 980–1584

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), pp. 21–35; Franklin and Shepard, The

Emergence of Rus,pp.245–77.

5 On the early cult see Gail Lenhoff, The Martyred Princes Boris and Gleb: A Socio-Cultural

Study of the Cult and the Texts (Columbus, Oh.: Slavica, 1989); Paul Hollingsworth, The

Hagiography of Kievan Rus’ (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1992), pp. xxvi–

lvii.

75

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

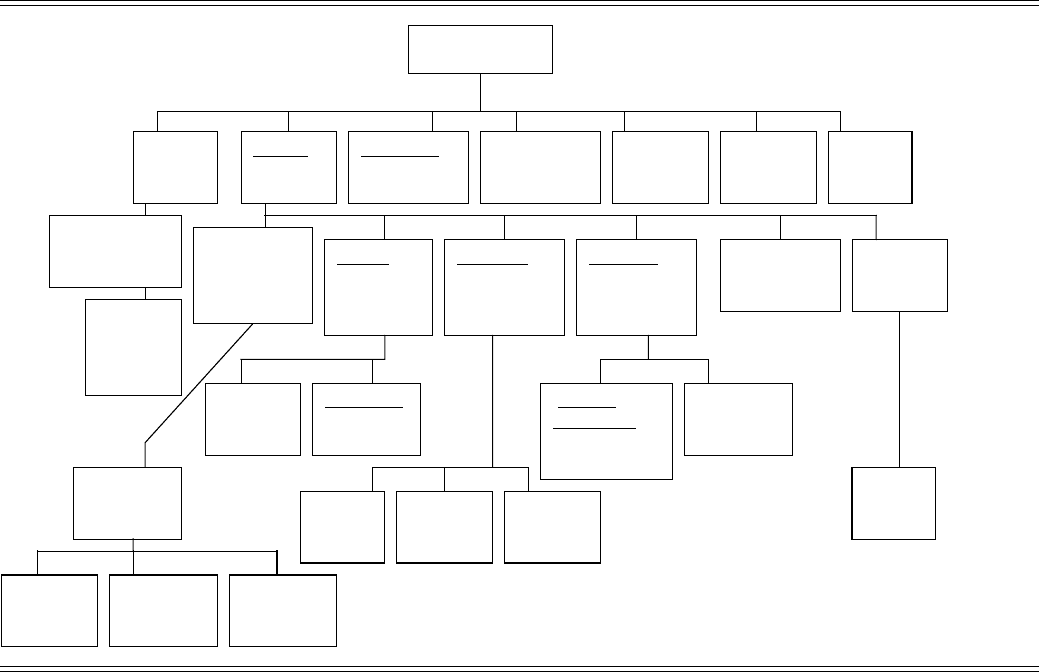

Table 4.1. From Vladimir Sviatoslavich to Vladimir Monomakh (princes of Kiev underlined)

VLADIMIR

Iziaslav

d. 1001

Iaroslav

d. 1054

Sviatopolk

d. 1019

Sviatoslav

d. 1015

Mstislav

d. 1034/6

Boris

d. 1015

Gleb

d. 1015

Briacheslav

d. 1044

Iziaslav

d. 1101

Polotsk

Vladimir

d. 1052

Iziaslav

d. 1078

Sviatoslav

d. 1076

Vsevolod

d. 1093

Viacheslav

d. 1057

Igor’

d. 1060

Rostislav

d. 1067

Riurik

d. 1092

Volodar

d. 1124

Vasilko

d. 1124

Sviatopolk

d. 1113

Iaropolk

d. 1086

David

d. 1112

Oleg

d. 1115

David

d. 1123

Iaroslav

d. 1129

Vladimir

Monomakh

d. 1125

Rostislav

d. 1093

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Kievan Rus’ (1015–1125)

Iaroslav of Novgorod, and Mstislav of Tmutorokan’ – emerged as the princi-

pal combatants. From their widely dispersed power bases each used his own

regional resources and contacts to reinforce the campaign for a secure place at

thecentre.Sviatopolk formedan alliance with the kingofPoland,whosemulti-

national force occupied Kiev for a while; Iaroslav augmented his local Nov-

gorodian forces with Scandinavian mercenaries who helped him eventually to

defeat and expel Sviatopolk; Mstislav gathered conscripts from his tributaries

in the northern Caucasus, with whose aid he was able (in 1024) to negotiate an

agreement with Iaroslav: he (Mstislav) would occupy Chernigov and would

control the ‘left-bank’ lands (east of the Dnieper), while Iaroslav would control

the ‘right bank’ lands including Kiev and Novgorod. Only on Mstislav’s death

(in 1034 or 1036) did Iaroslav revert to his father’s status as sole ruler.

6

Thus the death of Vladimir was followed by multiple fratricide, three years

of dynastic war, a further seven years of periodic armed conflict, then a decade

ofcoexistencebeforethefinalresolutionwhenjust one of Vladimir’snumerous

sons – Iaroslav – was left alive and at liberty. We can (and scholars do) speculate

as to how the succession in 1015 ‘should have’ worked. For such speculations to

have any value, we need to be reasonably confident of three things: (i) that we

know the seniority of his sons; (ii) that we know Vladimir’s own wishes; and

(iii) that we know what in principle constituted dynastic propriety at the time.

But we know none of these things. Even if we did, and even if we could thereby

in theory extrapolate a system to which his sons were meant to adhere, their

actions demonstrate that any notional system failed to function. For practical

purposes no such system existed.

The next change of generations, on Iaroslav’s death in 1054, was more

orderly. Like Vladimir, Iaroslav allocated regional possessions to his sons.

UnlikeVladimir–accordingto thePrimaryChronicle–hespecifiedahierarchyof

seniority both within the dynasty and between the regional allocations, and he

laid down some principles of inter-princely relations. The chronicle presents

Iaroslav’s arrangements in the form of what purports to be his deathbed

‘Testament’ to his sons, though it is possible that the document itself was

composed retrospectively.

7

6 Franklin and Shepard, The Emergence of Rus,pp.183–207. The precise course of events is

contentious: see e.g. I. N. Danilevskii, Drevniaia Rus’ glazami sovremennikov i potomkov

(IX–XII vv.) (Moscow: Aspekt Press, 1998), pp. 336–54;A.V.Nazarenko,Drevniaia Rus’ na

mezhdunarodnykh putiakh. Mezhdistsiplinarnye ocherki kul’turnykh, torgovykh, politicheskikh

sviazei IX–XII vekov (Moscow: Iazyki russkoi kul’tury, 2001), pp. 451–503.

7 Povest’ vremennykh let (hereafter PVL), ed. D. S. Likhachev and V. P. Adrianova-Peretts, 2

vols. (Moscow and Leningrad: AN SSSR, 1950), vol. i,p.108. See Martin Dimnik, ‘The

“Testament” of Iaroslav “the Wise”: A Re-Examination’, Canadian Slavonic Papers 29

(1987): 369–86.

77

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008