Ripper J. American Stories: Living American History. Volume 2: From 1865

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

A PALETTE OF PROGRESSIVES

79

5

A Palette of Progressives

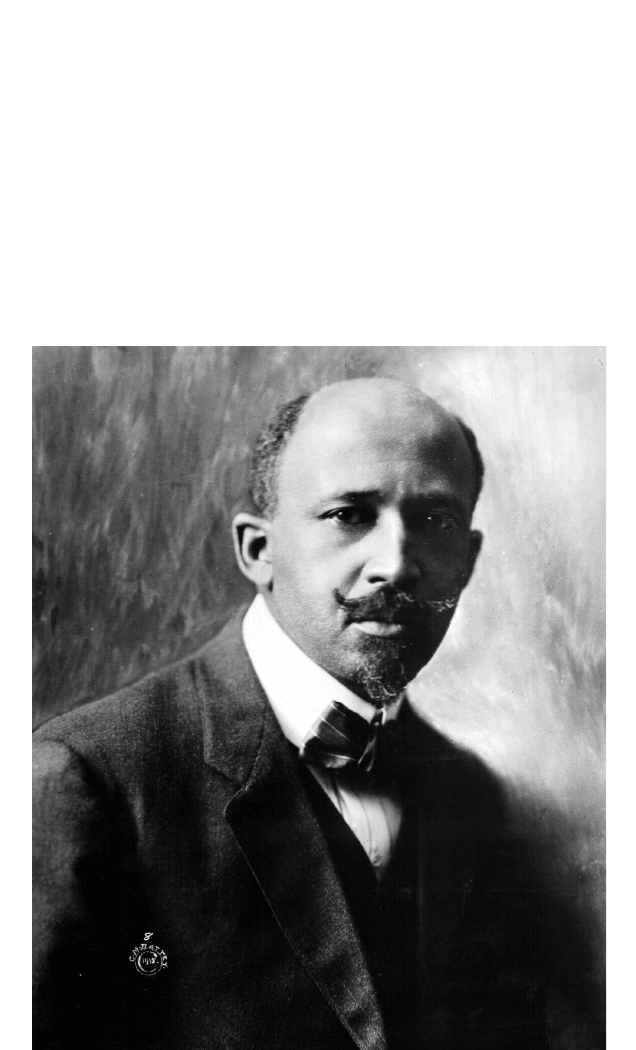

W.E.B. DuBois (C.M. Battey/Getty Images)

AMERICAN STORIES

80

The “Full Dinner Pail” and the “Square Deal”:

Theodore Roosevelt as President

During his successful presidential campaign in 1900, William McKinley and

his vice presidential running mate, Theodore Roosevelt, assured the electorate

a “full dinner pail,” plenty of food to eat along with all the other trimmings

of prosperity. In 1904, voters elected Theodore Roosevelt president after he

offered them a “square deal,” a slogan less well defined than a table spread

with food, but seeming nevertheless to promise the sort of fairness and good-

governance upon which Roosevelt staked his reputation. How well did he

deliver?

In

1900 there were 8,000 automobiles registered in the United States. By

1910, there were 458,000 registered automobiles. The dragging farm prices of

the 1890s had rebounded, and the average wage earner saw about a 20 percent

increase in wages over that same time, up to about $600 annually. Electricity

continued to fan out from cities to suburbs, though most rural areas would

have to wait until the 1930s and 1940s for electric power. Starting in 1907,

well-funded government specialists trained to weed out diseased meats and

dangerous drugs began inspecting food and pharmaceuticals. During a 1902

strike for higher wages, the federal government supported Pennsylvania coal

miners. First in Wisconsin, and then elsewhere in the Midwest and West,

legislatures wrote new forms of direct political action into law—referendums,

initiatives, primaries, and recalls—giving voters the chance to vote on laws,

propose new laws, choose candidates for elective office, and yank politicians

out of office. And there was more fun to be had in America, too.

Bicycles by the millions whirred over brick roads and country lanes. In-

n

ovative diamond-shaped frames and improved tires provided the convenience

and comfort needed to get women riding, even in a skirt. Susan B. Anthony,

the famous suffragist also famous for her stick-in-the-mud seriousness, said

bicycles had “done a great deal to emancipate women. I stand and rejoice every

time I see a woman ride by on a wheel.”

1

The leader of the Women’s Christian

Temperance Union, Frances Willard—noted for her sparkling advocacy of

a dry country—got such a boost from bicycle riding that she promoted its

delights in an 1895 book, A Wheel Within a Wheel: How I Learned to Ride the

Bicycle. Willard was sure that if women catapulted themselves onto the backs

of bikes, they could also spin a proper campaign to attain full citizenship,

namely the right to vote. She remembered being imprisoned by apparel on her

sixteenth birthday, “the hampering long skirts . . . with their accompanying

corset and high heels; my hair was clubbed up with pins.” Dutiful to tradition,

Willard stayed “obedient to the limitations thus imposed” by stifling clothes

and inhibiting expectations, but almost four decades later, overwhelmed by

81

A PALETTE OF PROGRESSIVES

overwork and grief for her mother’s death and needing “new worlds to conquer,

I determined that I would learn the bicycle.” What started out as an energizing

diversion soon became a means to convey her messages: “I also wanted to

help women to a wider world, for I hold that the more interests women and

men can have in common, in thought, word, and deed, the happier will it be

for the home. Besides, there was a special value to women in the conquest of

the bicycle by a woman in her fifty-third year.”

2

Besides inspiring women,

biking was a bonanza for industrialists, tinkerers, and retailers: Americans

purchased more than 10 million bicycles by 1900. And what better way to get

exercise than to pedal over to the nearest movie house? Tally’s Electric Theater

opened in 1902 in Los Angeles, the first building consecrated to movies and

movies alone, though the sixty-seven stately vaudeville buildings operating

in the nation by 1907 also showed movies—that ultimate freedom from care

and worry, if only for an hour or two. Americans were devising ways to make

themselves happy and rich at the same time.

It

would seem that Theodore Roosevelt at least presided over a “square

deal,” however much of it he may have been responsible for.

Not everyone in America had the chance to pedal the latest-model bicycle

or sink into the plush upholstery of a palatial vaudeville house. In particular,

European-Americans continued to shove African-Americans away from the

good jobs, the seven-gabled, oak-shaded neighborhoods, and the good fun

of this glittery, consumer-oriented, plentiful land of illusions. The Fourteenth

and Fifteenth Amendments guaranteed full civil rights to black people, and

the 1875 Civil Rights Act prevented any one individual from denying “the

full and equal enjoyment of any of the accommodations, advantages, facili-

ties,

and privileges of inns, public conveyances on land or water, theaters and

other places of public amusement” to any other citizen because of “race” or

“color.”

3

In 1883, however, the Supreme Court struck down the 1875 law, say-

ing that the regulation of individual behavior was a state matter. This ruling

left southern blacks at the mercy of white-controlled legislatures.

Then,

in its 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson ruling, the Supreme Court allowed

for a legally segregated America. An 1890 law in Louisiana stipulated that

railroad companies provide separate seating for whites and blacks—the only

exception allowing for black nurses tending to white babies. Homer Adolph

Plessy, a light-skinned mulatto with one-eighth African ancestry, donated

his body to test the law. In 1892, police summarily arrested Plessy for sitting

in the white seating, and his case made its way through the appeals system.

Eight Supreme Court justices ruled in favor of the Louisiana law, disagreeing

with the “assumption that the enforced separation of the two races stamps the

colored race with a badge of inferiority.” The only dissenting justice was John

Marshall Harlan of Kentucky. Although a former slave owner, Harlan had no

AMERICAN STORIES

82

trouble understanding the Constitution. He called the Louisiana segregation

law “hostile to both the spirit and the letter of the Constitution of the United

States” and deliberately intended to create the “legal inferiority [of] a large

body of American citizens”—which is precisely what happened.

4

The lie of

“separate but equal” became many white Americans’ favored illusion.

In 1890, when Louisiana passed the law segregating railroad cars, there

were sixteen black legislators in that state. By 1910 there were none. What

had been discrimination in practice became discrimination by law as southern

schools, water fountains, hotels, hospitals, public bathrooms, restaurants,

parks, and every other conceivable public place became racially divided, usu-

a

lly with the black facilities inferior in construction and amenities. Separation

itself was often a worse sting, though the leaking tarpaper roofs and the bit-

ing

chill of winter in the windblown hovels that served as African-American

primary schools inflicted their own pain. State and local officials prevented

African-Americans from registering to vote by using poll taxes, monetary

fees that most poor people—white or black—simply could not afford. Of-

ficials

also used literacy tests, which allowed the white examiners to interpret

a written passage in such a way as to pass or fail anyone they chose. And

they implemented “grandfather clauses” that permitted an illiterate man to

vote only if his father or grandfather had been registered prior to 1867 (when

not a single black person could vote). In these ways—and through violent

intimidation—white southerners prevented most black southerners from vot-

ing.

The dinner pail was at best half full in black America.

In the decades leading up to the Civil War, many white women, casting

their lot with the suffering slaves, had struggled for the immediate end to

slavery. When slavery ended with the Thirteenth Amendment, these fighting

abolitionists (like Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who had organized the Seneca

Falls Convention in 1848) expected to receive their own full citizenship rights,

especially the vote. Instead, the proposed Fifteenth Amendment specifically

omitted women, giving the vote only to men. Feelings of fury and betrayal

seeped into Elizabeth Stanton and her ally Susan B. Anthony, and they cam-

paigned against passage of the amendment.

In

1865, sensing a national mood favorable to black suffrage but opposed

to woman suffrage, Stanton wrote, “The representative women of the nation

have done their uttermost for the last thirty years to secure freedom for the

negro . . . it becomes a serious question whether we had better stand aside

and see ‘Sambo’ walk into the kingdom first.”

5

Her old friend and ally, Fred-

erick Douglass, naturally took offense at the “Sambo” reference, and they

split ways. In 1895, five years after leading suffragists created the National

American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), they excluded African-

American women from the annual convention held in Atlanta. The difficulty

83

A PALETTE OF PROGRESSIVES

of convincing people that women were suited to full citizenship turned many

white suffragists into pragmatists—if black women had to be excluded in

order to gain southern support, so be it.

The

remaining obstacles to female enfranchisement were many. Nearly

everyone felt that politics were corrupt and would corrupt women in turn. The

liquor industry’s brewers, distillers, saloon owners, and distributors rightly

feared that voting women would march to the ballot boxes and check “prohibi-

tion.”

Conservative women did not want to upset the traditional social order.

Many southerners assumed that any increase in the franchise would somehow

lead to a reversal of Jim Crow. Stanton, Anthony, and many of their white

suffragist sisters gave in to segregation in order to advocate for their primary

cause: getting the vote for themselves.

I

n 1908, when only four states—all in the West—had given women the vote,

President Roosevelt gave his opinion of enfranchising women. “Personally,”

he said to an Ohio member of NAWSA, “I believe in woman’s suffrage, but

I am not an enthusiastic advocate of it, because I do not regard it as a very

important matter.” He did not, however, think suffrage would “produce any of

the evils feared”—like siphoning women away from motherhood and into the

pigpen of politics. Roosevelt envisioned equality of spirit but not of action. “I

believe,” he wrote, “that man and woman should stand on an equality of right,

but I do not believe that equality of right means identity of functions.” There

were, in Roosevelt’s opinion, proper realms for women and men, and women

should be active at home because “the usefulness of woman is as the mother

of the family.”

6

Reality, however, had already antiquated his beliefs.

Argonia, Kansas, elected the nation’s first woman mayor, Susanna Salter,

in 1887. Seven years later, in 1894, voters elected three women to Colorado’s

state legislature. In 1902, women were more than 50 percent of the undergradu-

ate

students at the University of Chicago. All sorts of career fields opened

up to women: journalism, law, medicine, research, teaching, retail, clerical,

labor agitation, business ownership. Most middle-class working women quit

their jobs upon marriage, but poor women—white and black—generally had

to continue working, the average salary of the average husband being insuf-

ficient to support a family

.

Jane Addams, the pioneering social worker in Chicago who ran Hull House,

was America’s most respected reformer, and her star did not crash until she

spoke out as a pacifist during World War I. Unlike Addams, who never married,

Madam C.J. Walker—born Sarah Breedlove—knew family and fame. Born

to African-American sharecroppers, orphaned, early widowed, and remar-

ried,

Madam Walker concocted a scalp tonic that regenerated hair (or at least

cleaned the follicles well enough to let frustrated locks through to the light of

day). The lotion generated a fortune for her, and she toured the country setting

AMERICAN STORIES

84

up beauty schools and salons. During World War I, she raised bonds for the

war effort, keeping clear of Jane Addams’s descent into disrepute. Although

Madam Walker was an exception to the rule of impoverished black oppres-

sion,

she demonstrated the strength and will power of the socially damned.

As she put it, “I have built my own factory on my own ground.”

7

Neither

African-Americans nor women—and Madam Walker was both—passively

accepted the half-lives that white men offered as broken tokens of an elusive

American dream.

Defining “Pr

ogressivism”: Roosevelt and Robert La Follette

Historians usually dub the first fifteen years of the twentieth century “the

Progressive Era.” What does this phrase mean? In part it is historians’ ac-

ceptance

of a word, “progressive,” that certain politicians of the time applied

to themselves. Robert La Follette—congressman, then governor, and finally

senator from Wisconsin—called himself a “progressive” while, as governor,

he battled against others in Wisconsin who wanted to stymie his efforts to

make democracy direct. Ten years later, in 1912, Theodore Roosevelt, in a bid

to regain his old job, formed a new political party, the Progressive, or “Bull

Moose,” Party. He had suffered through the presidency of his old friend Wil-

liam

Howard Taft—whom Roosevelt did not think had the mettle that a chief

executive needed. Now Roosevelt draped himself in a “progressive” aura. If

Teddy Roosevelt and Battling Bob La Follette were both “progressives,” did

they share more than the name? How did their behavior define the term?

Since the 1890s, farmers, including the Wisconsin dairy farmers who were

La Follette’s constituency, and small communities regularly complained about

the seemingly arbitrary prices set by railroad companies. Governor La Follette

took up their cause with the theatrical flourish expected from a former Shake-

spearean

actor (who as a young man decided he was too short for the stage).

La Follette enlisted the data-rich testimony of professors from the University

of Wisconsin. Academics had founded the new fields of sociology, economics,

and anthropology on a shared premise: human society could be understood

and improved. La Follette realized the credibility that trained scholars could

bring to his case, and his ploy worked: in 1905 the Wisconsin Railroad Com-

mission

got the authority to oversee railroads and to modify their rates. (Then

again, the professors from the university demonstrated in their reports that

the railroads were not as capricious as La Follette and his constituents had

argued. Academics were already hard at work upsetting everybody.)

As president, Roosevelt more than once relied on similar tactics: coercing

recalcitrant lawmakers into going along with his ideas in the threatened (and

sometimes revealed) face of evidence compiled by experts. When Sinclair

85

A PALETTE OF PROGRESSIVES

Lewis’s book The Jungle was published in 1906, the public grabbed the first

25,000 hot copies and read them with dismay. The Chicago meatpacking

industry apparently had no standards other than to sell “everything but the

squeal.” And “everything” seemed to include rat poison, rat bodies, rat dung,

and any other fleshy matter that happened to end up in a meat grinder. Neither

the public nor Congress had been wholly unaware of the meatpackers’ lax

standards, but Sinclair’s imagery turned enough stomachs to throw the issue

directly into Congress’s lap. When certain legislators resisted passing laws

to better regulate conditions in the stockyards, slaughterhouses, and canning

factories, Roosevelt ordered a commission to immediately investigate and

produce a report. The report came in two parts, the first of which had fewer

disgusting details. Roosevelt released this to the newspapers and threatened

to release the second half, which could have scandalized anyone opposed to

new regulations. On January 1, 1907, the Meat Inspection Act passed, giving

$3 million more to fund the previously cash-poor meat inspectors. The Pure

Food and Drug Act, which established the Food and Drug Administration

(FDA), also became law. While Roosevelt had used La Follette’s tactics to

improve the safety of food and drugs, he resorted to backroom deal making to

convince oppositional congressman to strengthen the government’s oversight

of railroads. Roosevelt was as comfortable wielding the scientific lingo of

progressive reformers as he was chewing cigars with congressmen he may

not have liked but whose votes he needed.

B

elieving that corporate growth was inevitable and often beneficial, Roos-

e

velt was not opposed to big corporations as a rule, although he did think trusts

and mammoth companies ought to be regulated, particularly the railroads.

He shared this peeve with La Follette. Besides, Roosevelt wanted to court

southern voters into the Republican Party, and southern farmers yowled about

the railroads. So there was political capital to be won by lassoing companies

like the Southern Pacific. As it turned out, Roosevelt’s lasso could not really

restrain a railroad. In order to strengthen the Interstate Commerce Commission

(ICC) through the Hepburn Act of 1906, Roosevelt and his congressional al-

lies

had to agree to a disappointing proviso: federal courts could veto any rate

adjustments that the ICC made. That was politics at its most stereotyped—in

order to get anything done, so much water got added to laws that they leaked.

But still Roosevelt could present himself as having made progress with regard

to unfair shipping rates.

F

rom the politicians’ point of view, then, being a progressive meant adjust-

ing

the laws or creating new ones in such a way that government oversaw

business, economy, and labor with an eye toward fairness for all. Except for

the 4 to 6 percent of voters who voted for the Socialist Party ticket, most

Americans—including typical progressives—thought capitalism was a work-

AMERICAN STORIES

86

able arrangement, one that rewarded thrift, hard work, ingenuity, skill, and a

sprig of luck: all parts of the American character. Progressives might differ

in the extent of government involvement they sought (La Follette thought the

Hepburn Act was weak and not worth much), but they generally agreed on

establishing safeguards and basic rules of conduct in order to stabilize what

was obviously becoming the greatest economy ever known.

A

person could be a progressive but not an elected official. Though the Con-

stitution

had created a representative republic rather than a direct democracy,

that did not mean that Americans were prevented from participating as they

saw fit. With the emergence of national magazines and newspapers, a citizen

could stoke the hot embers of public opinion just as surely from an editor’s

desk as from a governor’s. Ida Tarbell demonstrated the power of the citizen’s

pen in her running history of John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil (which led

in 1911 to a “trust-busting” that separated Standard Oil into thirteen smaller

companies, one of which is known today as Exxon-Mobil). Other citizens

also used the press, along with their business and political contacts, to adjust

society. Jane Addams, Madam C.J. Walker, Booker T. Washington, and W.E.B.

DuBois were all progressives, each in her or his own way, though not one of

them ever held elective office.

Different Paths to Progress: Booker T. Washington, W.E.B.

DuBois, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Frances Willard

In 1895 at the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta, Georgia,

a handsome ex-slave named Booker T. Washington took the podium and

spoke a two-part harmony that led to his ascendancy as a premier spokes-

m

an for African-American rights. (However, not all African-descended

citizens of America recognized Washington’s leadership.) Under a southern

sun, Washington did his best to reassure a largely white audience in order

to gain their cooperation. Jim Crow was setting in, sometimes in the ugliest

ways imaginable. Many whites used lynching as a public tool and spectacle,

a kind of macabre sport. Audiences of white families numbering in the tens,

hundreds, and thousands (including children) would arrive at a prearranged

destination (often advertised by railroads) and participate in the hanging,

burning, mutilation, and butchering of black men. It was common for white

people to rush a tied-up black man, cut off his ears, cut off his nose, pour oil

onto the kindling underneath him, and cheer as he burned. Then they would

dig through the ashes for body-part souvenirs. Photos were taken. The pho-

tos

got turned into postcards. Between 1882 and 1901, at least 2,000 people

were lynched in the United States, 90 percent of them black and nearly all

in the South. Booker T. Washington knew his people’s plight, and he knew

87

A PALETTE OF PROGRESSIVES

that white people were speeding up segregation, so he reached for an accom-

modation, a compromise.

At

the heart of Washington’s speech lay this thought: “In all things that are

purely social we can be as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all

things essential to mutual progress.” Blacks will accept social segregation in

return for jobs—that is what his speech boiled down to. It was folly to recruit

foreign immigrants to work in the South’s growing factories, Washington told

the whites in the audience, because there was already an eager, trustworthy

pool of available laborers—African-Americans. And it was folly, Washington

said to the black people in the audience, to expect to be elected mayor or made

president of a bank. “We shall prosper,” he said, “in proportion as we learn to

dignify and glorify common labour, and put brains and skill into the common

occupations of life.” Work in the fields, he told his black listeners. Work in

the factories, and for now, forget the loftier dreams: “No race can prosper till

it learns that there is as much dignity in tilling a field as in writing a poem.

It is at the bottom of life we must begin, and not at the top. Nor should we

permit our grievances to overshadow our opportunities.”

8

This was a message

that white supremacists could accept. This was not a message that all black

people thought proper or fitting. W.E.B. DuBois labeled Washington’s speech

“the Atlanta Compromise,” a phrase that could be interpreted as compliment

or criticism—or both.

9

W.E.B. DuBois emerged as Washington’s leading African-American critic.

While Booker T. Washington was establishing the Tuskegee Institute in Ala-

bama,

the center of the cotton South, DuBois earned a PhD at Harvard (the

first African-American to do so) and set to work writing one essay or book

after another. At Tuskegee, Washington taught what were considered practi-

cal,

applicable skills like agricultural science and machining. Washington’s

educational efforts certainly had their successes: from 1900 to 1910, African-

American literacy improved by half, up to 70 percent. At nearby Atlanta Uni-

versity

, DuBois framed a theory of race advancement in which he proposed

that a “talented tenth” of African-Americans receive top-notch educations

and then lead the rest of the race to success and equality, even if they had to

do so without the cooperation of white people.

10

Both men wanted the same

thing for African-Americans, but at least in public they advocated separate

paths, and they used radically different language.

In DuBois’s 1903 book The Souls of Black Folk, he called Booker T.

Washington’s methods a “programme of industrial education, conciliation of

the South, and submission and silence as to civil and political rights.” Protest-

ing

that “narrow” vision, DuBois favored instead the example of Frederick

Douglass, who had “bravely stood for the ideals of his early manhood,—

ultimate

assimilation through self-assertion, and no other terms.” Douglass,