Siegel S., Siegel B. The Encyclopedia Of Hollywood

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

women, but they weren’t the “right” papers, and she didn’t

reach the diehard fans the way Parsons and Hopper did.

Unlike the other two columnists, Graham tended to report

facts rather than rumor. Perhaps her love affair with the ail-

ing F. Scott Fitzgerald during the last four years of his life

also made her far more aware of the fact that people live in

exceedingly fragile glass houses.

The power of all three of these women was such that the

movies themselves could hardly ignore them. Parsons

appeared as herself in Hollywood Hotel (1937), Without Reser-

vations (1946), and Starlift (1951). Hopper played herself in

Breakfast in Hollywood (1946), Sunset Boulevard (1950), and

The Oscar (1966). Graham did them both one better by hav-

ing

DEBORAH KERR

play her in the film version of her rela-

tionship with Fitzgerald, The Beloved Infidel (1959).

The power of these three gossip columnists began to

wane with the end of the

STUDIO SYSTEM

in the late 1940s

and 1950s, or, rather, it was diminished by fierce competition

from newer, younger gossip columnists who were in touch

with the changing nature of celebrity worship. A younger

generation was interested in TV stars, rock ’n’ rollers, and

sports personalities as well as movie stars.

Columnists such as Walter Winchell, Earl Wilson, Ed

Sullivan, Dorothy Kilgallen, Cholly Knickerbocker, and oth-

ers grew in popularity during the 1940s and 1950s.

In more recent years, gossip columnists such as Liz

Smith, Rona Barrett, Cindy Adams, Suzy, and Claudia

Cohen have held sway. None of them are gossip columnists

who concern themselves solely with the movies as did the big

three of gossip’s golden era.

Ironically, gossip has never been more widely dissemi-

nated than it is today. From tabloids such as The National

Enquirer and The Star to slick magazines such as People and

Us, and from TV shows such as Entertainment Tonight, the

amount of gossip emanating out of Hollywood is staggering.

It is, however, rather tame compared to the often outlandish

and mean-spirited stories that were written during the days

of Parsons and Hopper.

Grable, Betty (1916–1973) Though neither a great

talent nor a ravishing beauty, her famous pin-up pose during

World War II helped her to become an unlikely sex star. Her

persona as the slightly sexy girl-next-door made her a popu-

lar actress-singer-dancer in 1940s light musicals, as well as

Hollywood’s highest paid female star.

Her stardom didn’t come easily. Grable and her mother

left St. Louis for Los Angeles when the young girl was 12 years

old. She studied dance and, pushed by her mother, appeared in

the chorus of her first musical, Let’s Go Places, in 1930. She can

be spotted in dozens of films of the 1930s, either in the chorus

or in speciality numbers, but none of the studios thought she

had sufficient star quality to carry her own films.

At one time or another during the decade, she danced and

sang for Goldwyn, RKO, and Paramount, but not until she

married former child star

JACKIE COOGAN

in 1937 did she

begin to receive press attention. The marriage ended in 1940,

but her career began its upswing from about the time she

appeared on Broadway in the hit musical Du Barry Was a

Lady. This time,

TWENTIETH CENTURY

–

FOX

took a gamble

on her, and it paid off handsomely.

Down Argentine Way (1940) and Tin Pan Alley (1940)

launched her starring career. Much was made of her legs by

the press and the public, and she obliged both during World

War II by posing for a photo that became a favorite of Amer-

ican G.I.s. It was so popular, in fact, that Fox titled one of her

films Pin-Up Girl (1944). As a major publicity stunt, Fox also

insured Grable’s gams for $1 million with Lloyd’s of London.

Grable’s films were mostly backstage musicals, such as

Coney Island (1943) and Sweet Rosie O’Grady (1943). The films

don’t hold up very well, but they were extremely successful at

the time of their release. After the war ended, she was still at

the top of the heap with The Dolly Sisters (1946). But the end

for Grable was coming. After a series of pleasant, if nonde-

script, musicals that paired her with Dan Dailey, MGM was

reaching the height of its golden musical period with stars

such as

JUDY GARLAND

,

FRED ASTAIRE

,

GENE KELLY

, and

FRANK SINATRA

and directors of the calibre of

VINCENTE

MINELLI

and

STANLEY DONEN

. Neither Fox nor Grable

could compete, and box office fell off drastically.

Grable’s last shining moment was in How to Marry a Mil-

lionaire (1953), in which she appeared with

LAUREN BACALL

and

MARILYN MONROE

. According to the 1960 biography

Marilyn Monroe, written by Maurice Zolotow, Grable

reportedly told the blonde bombshell, “Honey, I’ve had it.

Go get yours. It’s your turn now.”

She appeared in just a handful of films in the 1950s, and

made her living in nightclubs and dinner theaters thereafter,

making a triumphant return to Broadway as a replacement

Dolly in Hello, Dolly! before dying of lung cancer at the age

of 56.

Graham, Sheilah See

GOSSIP COLUMNISTS

.

Grant, Cary (1904–1986) Possessing an exquisitely

charming voice, dashing good looks, and rakish nonchalance,

Cary Grant was the epitome of sophistication; yet he never

came across as effete or snobbish. He was also a comforting

screen presence whose image never seemed to change. In a

variation on The Picture of Dorian Gray, Cary Grant seemed

to preserve his youth while his audiences grew older. Also, if

never considered a versatile or masterful actor, he played

“Cary Grant” to perfection.

Born Archibald Leach in Bristol, England, to divorced

parents, the future actor lived in extreme poverty, scraping

for a living like a character out of a Dickens novel. It has

often been said that Archie Leach deliberately turned himself

into the urbane Cary Grant as a means of obliterating any

memory of his past.

While a teenager, he joined an acrobatic act and came to

America with them in 1920. He quit the act in the United

States and hit the vaudeville circuit with a mind-reading rou-

tine. None too successful in America, he returned to England

in 1923 and broke into the theater, playing modest roles in

GRABLE, BETTY

178

musical comedies. Spotted on the London stage, he was hired

for an Oscar Hammerstein musical on Broadway called

Golden Dawn.

His stage career was soon well established. With the

advent of sound motion pictures, Grant (like so many other

stage-trained actors) saw an opportunity to make big money.

He went to Hollywood but managed only to get a job at

Paramount feeding lines to an actress who was being screen-

tested. The actress remains unknown; Grant was discovered.

He had been right—there was big money to be made in Hol-

lywood; his starting salary was $450 per week.

His first film was a musical, This Is the Night (1932), in

which he had a modest role. In a string of films he had sup-

porting parts, including the heavy who nearly destroys

MAR

-

LENE DIETRICH

in Blonde Venus (1932) and

MAE WEST

’s foil

in She Done Him Wrong (1933) and I’m No Angel (1933). He

kept getting plenty of work, but he hadn’t truly become a star,

as evidenced by his having to wear a moustache in The Last

Outpost (1935).

1936 was the year that Grant suddenly began to shine at

the box office. As is often the case, a combination of the right

script, the right chemistry between costars, and the right

director made an actor who had previously appeared in 20

films suddenly catch on with the public. The movie was

Sylvia Scarlett; his costar was

KATHARINE HEPBURN

; and the

director was

GEORGE CUKOR

.

But Grant’s contract was finished with Paramount before

Sylvia Scarlett was released. He was a free agent when he sud-

denly became a major star. In a unique arrangement, Grant

signed a nonexclusive contract with two studios, Columbia

and RKO, and he even managed to win script approval. He

was now master of his own fate, and very few stars have ever

chosen their films more wisely than Cary Grant.

Grant worked with Hollywood’s most inspired directors.

As a consequence, the actor starred in a substantial number of

top-notch movies. For instance, Grant appeared in

HOWARD

HAWKS

’s wonderful screwball comedies Bringing Up Baby

(1938), His Girl Friday (1940), I Was a Male War Bride (1949),

and Monkey Business (1952). He also distinguished himself in a

Hawks drama, Only Angels Have Wings (1939).

When it came to drama, though, Grant was at his best in

the films of

ALFRED HITCHCOCK

, appearing in some of the

master’s best films, Suspicion (1941), Notorious (1946), To Catch

a Thief (1955), and North by Northwest (1959).

Grant worked with other great directors as well, such as

George Stevens (Gunga Din, 1939), George Cukor (Holiday,

1938, and The Philadelphia Story, 1940), Leo McCarey (The

Awful Truth, 1937, and An Affair to Remember, 1957), and

FRANK CAPRA

(Arsenic and Old Lace, 1944).

The number of quality films in which Cary Grant starred

is staggering, and he was rarely between hit movies during his

long career—with only one exception. In 1953–54, after one

mediocre film, Dream Wife (1953), he disappeared from

movie screens for nearly two years; it was generally assumed

that none of the studios wanted a 50-year-old leading man

(despite his youthful appearance). But the real reason he was

absent from movie screens for two years had nothing to do

with his lack of appeal: he had agreed to star in two films, but

both deals fell through because of Grant’s own ambivalence

about the parts. Had he actually played those two roles, there

may have been that many more quality films to add to his

already impressive list. The movies he was supposed to

appear in were Sabrina (1954) and A Star Is Born (1954).

Grant remained immensely popular throughout the late

1950s, and well into the 1960s. His last film, Walk Don’t Run

(1966), was a money-maker. But Grant was offered the direc-

torship of the Fabergé cosmetics company, and he opted to

leave his movie career while he was still on top.

Very few actors have walked away from the limelight as

Grant did. Even

JIMMY CAGNEY

returned to films after a 20-

year retirement. But not Grant. He was America’s best-look-

ing senior citizen, and movie fans the world over lamented

his abandoning the silver screen.

Somehow, in all his years in Hollywood, Grant had never

received an Oscar, but the academy belatedly rectified that

error by presenting the actor with a special award “for his

unique mastery of the art of screen acting.” Certainly, there

was hardly another actor who made it seem so easy.

Once, a few years before his death, he had forgotten his

ticket to a charity fund-raiser, so he went to the ticket taker

and explained his problem, telling the woman that he was

Cary Grant. She shook her head, saying “That’s impossible.

You don’t look like Cary Grant.” To which the imperturbable

actor replied smiling, “Who does?”

See also

SCREWBALL COMEDY

.

Grapes of Wrath, The The socially and politically con-

scious classic 1940 film that proved that controversy could be

big business. The movie was both a courageous undertaking,

because of its prolabor stance, and also a beautifully written,

acted, photographed, and directed work of lasting power.

Based on the John Steinbeck novel of the same name, The

Grapes of Wrath was bought outright by

DARRYL F

.

ZANUCK

of

TWENTIETH CENTURY

–

FOX

for $100,000. Unlike most

authors, who generally despise the film versions of their

work, Steinbeck had a grudging respect for the adaptation of

his Pulitzer Prize–winning book by Zanuck, director

JOHN

FORD

, and screenwriter

NUNNALLY JOHNSON

.

The Grapes of Wrath documented the devastation of the

early 1930s drought that carved the Dust Bowl on large areas

of the lower Midwest and the poor Okies who lost their land

in cruel foreclosures. The movie version of the story was nec-

essarily trimmed, with characters eliminated and a long flood

scene removed. Nonetheless, the spirit of the novel was

maintained by following the fortunes of one Oklahoma fam-

ily, the Joads.

Few in the film industry felt that a movie could be made

from such a controversial novel. Zanuck, to his credit, felt

otherwise, and hired one of the best directors available, John

Ford, once he had a script he liked. Ford, himself, was

attracted to the story because it was so much like the famine

in Ireland that had affected his own family.

Casting the film was the next problem. Ford wanted the

thin and brittle Beulah Bondi for Ma Joad, but Zanuck

wanted the film cast with Fox contract players, and Jane

GRAPES OF WRATH, THE

179

Darwell was his choice for the Joad family matriarch;

Zanuck had his way. Though Darwell won an Oscar for Best

Supporting Actress as Ma Joad, there are critics who still feel

that she’s the weakest member of the cast. Zanuck, however,

also wanted either

DON AMECHE

or

TYRONE POWER

, Fox’s

two biggest male stars, to play Tom Joad, the idealistic hero

of the movie. Ford wanted

HENRY FONDA

, and Fonda

wanted the part, as well. To get the role, the actor had to

agree to a seven-year contract with Fox.

The final cast for The Grapes of Wrath included Henry

Fonda (Tom Joad), Jane Darwell (Ma Joad), John Carra-

dine (Casey), Charley Grapewin (Grampa Joad), Dorris

Bowdon (Rosasharn), Russell Simpson (Pa Joad), and John

Qualen (Muley).

Ford sought an artful authenticity in The Grapes of Wrath,

which he more than received from his actors, none of whom

wore makeup. Cinematographer

GREGG TOLAND

captured

the poverty of the Okies in harsh black-and-white shots that

seemed almost documentarylike. At the same time, he

showed the destruction of the land by dust storms in a series

of startlingly bleak scenes.

After the movie was shot, Zanuck added a new ending to

the film. Originally, it was to have ended with Tom Joad

heading up over a hill, a symbol of (among other things) the

labor movement. That scene was kept, but Zanuck wrote Ma

Joad’s final speech that included the memorable sentiment:

“We’re the people that live. Can’t nobody wipe us out.” The

original ending was more ambivalent. Zanuck’s change added

a bit of hopefulness.

When the movie opened, it met with immediate and

unequivocal praise. That praise has never diminished. The

movie represents one of Hollywood’s shining moments of

courage coupled with cinematic expertise and art.

In addition to Jane Darwell’s

ACADEMY AWARD

, the

movie brought John Ford the Oscar for Best Director. The

film was nominated for Best Picture and made Henry Fonda,

nominated for Best Actor, a star of the first order, firmly

establishing his noble, honest, and upright image.

Great Train Robbery, The This seminal film in the

development of the art of moviemaking was directed by

Edwin S. Porter in 1903. The Great Train Robbery was the

longest movie of its day at 12 minutes, and it told a cohesive

story using intercutting, a panning shot, and a famous close-

up—a cowboy shooting his gun into the camera lens—at the

end of the film. None of these filmmaking techniques were

new—Porter, himself, had pioneered their use in his earlier

films—but it was the first time that they had been used all at

once and to such dramatic effect. The Great Train Robbery was

a huge hit and remained one of the most popular movies of

the early silent era, shown and reshown for more than a

decade before its artistry was finally overshadowed by the

growing sophistication of directors such as

D

.

W

.

GRIFFITH

.

The Great Train Robbery told a simple story of a band of vil-

lains who sneak aboard a train, rob it, and are then chased on

horseback by a posse until they are gunned down in the woods

while dividing up their loot. Shot in the wilds of New Jersey

with what was then a massive cast of 40, the movie established

the direction and content of future westerns, incorporating

the classic elements of the chase and the showdown.

Porter, though a genuine innovator, was ultimately more

concerned with the mechanics rather than the art of

moviemaking. Yet his contribution to the early growth of the

cinema cannot be underestimated.

Greenstreet, Sydney See

THE MALTESE FALCON

.

Grier, Pam (1949– ) Pam Grier is a tall, talented, beau-

tiful African-American actress who has been appearing in films

since 1970, but she has been misused, miscast, and overlooked

for good roles. In part, this is because she early on was the

queen of the

BLAXPLOITATION FILMS

in which she assumed the

persona of a woman whose physicality poses threats to drug

dealers and ne’er-do-wells of every sort, but it is also because

there are few good parts for African-American women.

Born in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, Grier was the

daughter of an air force mechanic whose work took him to

England and Germany. The family eventually settled in Den-

ver, Colorado, where she was, at the age of 18, first runner-

up in the Colorado Miss Universe pageant. She signed with

an agent and moved to Los Angeles, where she worked at

ROGER CORMAN

’s studios. Thanks to Corman, she made her

film debut in Beyond the Valley of the Dolls (1970), followed by

The Big Doll House (1971), in which she played one of several

convicts attempting a jail break. The success of this film led

to a sequel, The Big Bird Cage (1972), with a similar cast of

characters. The following year she appeared in Scream, Blac-

ula, Scream, playing a voodoo priestess. Her first significant

role, as the nurse in Coffy (1973), had her feigning drug

addiction to find and take revenge on the drug dealers

responsible for her sister’s addiction and death.

This role established her in the blaxploitation genre, and in

Foxy Brown (1974) she played essentially the same role, going

undercover as a prostitute to again seek vengeance, this time

for the deaths of her boyfriend and her brother. A cult icon and

role model for blacks and women, she was incredibly popular,

gracing the covers of Ms. and New York magazines. (She also

posed nude for Playboy.) Similar roles were as a detective in

Sheba, Baby and as an investigative photographer/reporter in

Friday Foster (both 1975). Perhaps aware that she was in dan-

ger of being permanently typecast, she appeared with

RICHARD PRYOR

in Greased Lightning (1977), a film about a

race-car driver, and then she stopped making films.

After a four-year hiatus, she resurfaced as a murderous

prostitute in the critically acclaimed Fort Apache, the Bronx

(1981), but aside from another significant role in Above the

Law (1988), most of her appearances were in small parts or in

starring roles in made-for-television films; most of them con-

cerned drugs. The only exception was her role as marathon-

runner

BRUCE DERN

’s lover in On the Edge (1986).

In the 1990s, she was reunited with fellow blaxploitation

stars

JIM BROWN

, Fred Williamson, and Richard Roundtree

in Original Gangstas (1996), in which the quartet reprised

GREAT TRAIN ROBBERY, THE

180

their roles and overcame the bad guys. The following year, in

the title role in Jackie Brown, which

QUENTIN TARANTINO

, a

fan, wrote for her, she played a sexy, seen-it-all flight atten-

dant who works for an arms dealer but wants to get out of the

racket. For her role, she received a Golden Globe nomina-

tion and praise from the critics. Since then, she has appeared

as a detective in the comedy Jawbreakers (1999), as the girl-

friend of

HARVEY KEITEL

in Holy Smoke (1999), and in the

horror film Bones (2000).

Griffith, D. W. (1875–1948) Unquestionably, the sin-

gle most-important filmmaker in Hollywood history, Griffith

understood the potential for artistic expression in the fledg-

ling movie business and with a ready supply of creativity and

ingenuity fashioned a visual language for telling stories in

moving pictures.

David Wark Griffith was the son of Colonel “Roaring

Jake” Griffith, a Confederate hero of the Civil War who went

bankrupt and died when Griffith was 10 years old. The boy

had to do his best to help his family survive, working as a

clerk in a store and at several other odd jobs, but he wanted

to be a writer and a dramatist. His luck in those arenas was

not very great, and he had to make his living as an actor. Call-

ing himself Lawrence Griffith because he was ashamed of the

way he earned his money, he toured the country in small

stock companies, often supplementing his meager income

with odd jobs.

In 1907, broke and in desperate need of employment (he

had married in 1906), Griffith took a stab at the movie busi-

ness, hoping to sell his story ideas. He went first to the Edi-

son studio and sought out

EDWIN S

.

PORTER

, a pioneering

director who, four years earlier, had made

THE GREAT TRAIN

ROBBERY

. Porter wasn’t interested in Griffith’s stories, but he

offered him a job as a movie actor.

For a stage actor, working in the movies was the ultimate

humiliation, but Griffith swallowed his pride and took the

job, appearing in Rescued from an Eagle’s Nest (1907).

GRIFFITH, D. W.

181

The most influential director in the history of film is D. W. Griffith, who almost singlehandedly invented the language of the

cinema.

(PHOTO COURTESY OF MOVIE STAR NEWS)

In 1908, Griffith was still trying to sell his story ideas, this

time to the

BIOGRAPH

company. They bought his stories and

hired him as an actor, as well.

Biograph was a small, not terribly successful film com-

pany in 1908, but Griffith took an interest in directing and

was given the opportunity with a film called The Adventures of

Dolly (1908).

G

.

W

. “

BILLY

”

BITZER

wasn’t Griffith’s camera-

man on the film, but he did offer helpful advice, and the two

men worked together afterward for 16 years in unarguably

cinema’s most important artistic union. At the time, however,

Bitzer didn’t think very much of Griffith. “Judging the little

I had caught from seeing his acting,” Bitzer later remarked,

“I didn’t think he was going to be so hot.”

The Adventures of Dolly, however, became a hit, and Grif-

fith quickly took over the creative reins of Biograph. Accord-

ing to Iris Barry’s famous monograph on Griffith published

by the Museum of Modern Art, “all of Biograph’s films from

June 1908 until December 1909 were made by Mr. Griffith,

and all the important ones thereafter until 1913.”

Biograph prospered like never before. By 1911, Griffith

had dropped the name Lawrence and forever after used his full

name David Wark Griffith; he was finally proud of his work.

From the very beginning at Biograph, Griffith experi-

mented and developed the language of film. In For Love of

Gold (1908), he changed the camera setup in the middle of a

scene, bringing it closer to the actors. It had never been done

before. With Bitzer, he also created the fade-in, the fade-out,

and numerous other technical storytelling tools.

As he directed Bitzer to take more and more close-ups,

Griffith understood that the new art form needed a new kind

of actor whose face could stand the scrutiny of the camera.

He hired teenagers, such as

MARY PICKFORD

,

MABEL NOR

-

MAND

, Mae Marsh, Blanche Sweet, and Dorothy and

LIL

-

LIAN GISH

, all of whom would become major movie stars.

In 1909, in The Lonely Villa, he further developed the use

of cross-cutting between scenes. It was a technique that

would come to glorious fruition in Griffith’s masterpiece, The

BIRTH OF A NATION

(1915).

Griffith not only extended the language of motion pic-

tures, but he also extended their length. He was the first to

shoot a two-reel film (each reel was 10 minutes long), and he

kept making his films longer until The Birth of a Nation

reached the unheard of length of 12 reels.

Griffith had to leave Biograph in 1913 to continue his

artistic growth. When he left, he took Bitzer with him as well

as his loyal stock company of actors. He soon began work on

the film that would change the course of moviemaking, The

Birth of a Nation.

He had budgeted The Birth of a Nation at $30,000, but it

cost nearly $100,000. It was of no matter; Griffith’s movie

was a colossal hit, earning an estimated $18 million. But

because of attacks on the film due to its racist elements, Grif-

fith felt compelled to show his tolerance by making Intoler-

ance (1916), a hugely expensive epic on the evils on hatred.

For all its grandeur, the film was a financial disaster. A

pacifist movie made just as America was being primed to

enter World War I, it didn’t stand a chance. Griffith lost a

fortune. The film, however, remains a testament to his

incredible vision. The sets, the huge cast, and the enormous

spectacle of the movie were truly awesome and remain so

even by today’s standards. Though Intolerance was a failure in

America, the film played for 10 continuous years in the

USSR, and it clearly influenced the work of

CECIL B

.

DEMILLE

, Abel Gance, and

FRITZ LANG

.

In 1919, Griffith joined with the other great silent-screen

giants

CHARLIE CHAPLIN

, Mary Pickford, and

DOUGLAS

FAIRBANKS

to form

UNITED ARTISTS

. Griffith’s first film for

the new company was Broken Blossoms (1919) with Lillian

Gish and

RICHARD BARTHELMESS

. It was an achingly simple

story of interracial love that played to large audiences and

excellent reviews. It is considered an important movie in the

development of film art because of its subtle attention to

visual detail.

He followed that success with several other films, the

most popular being Way Down East (1920) and Orphans of the

Storm (1922). In 1924, he made America, a sweeping story of

the Revolutionary War, but financial considerations finally

drove him out of independent production, and his career

went into serious decline.

One would think that the coming of talkies would have lit-

erally sounded the death knell for any hope of a Griffith

comeback, but he made Abraham Lincoln in 1930, and the film

received good reviews and did respectable business. However,

his next film, The Struggle (1931), was a bomb. Griffith retired

from the movie business, though he reputedly had some

involvement in One Million Years

B

.

C

., a 1940 film.

He died a forgotten man in 1948, but he has since been

remembered and honored. As critic Andrew Sarris wrote in

The American Cinema, “The cinema of Griffith, after all, is no

more outmoded than the drama of Aeschylus.”

grip The crew of a film is divided into two groups, the

electricians and the grips. Electricians are responsible for

providing power for the lighting equipment, and the grips

handle everything else. In the theater, a grip would be

referred to as a stagehand. In essence, grips are laborers who

carry out a multitude of jobs on a movie set. Often, the grips

are subdivided by their job functions, such as construction

grips, lighting grips, dolly grips (the people responsible for

laying the dolly tracks and also moving the dolly during the

shoot), and so on.

The origin of grip is rather prosaic. The word was first

used to describe laborers who literally “grip” scenery, scaf-

folding, lighting diffusers, and so on in the course of their job.

The person in charge of all the grips is known as the key grip,

whose assistant is the grip best boy.

The key grip’s relative station on the set of a film is

equal to that of the gaffer, who is the chief electrician. The

key grip works in tandem with the gaffer and reports to the

cinematographer (or director of photography). The key

grip’s job title did not come into being because it is a key

position (though it is), but because the key grip has tradi-

tionally been the person who carries the keys for various

locked storage spaces.

See also

BEST BOY

;

DOLLY

;

GAFFER

.

GRIP

182

Hackman, Gene (1931– ) A prolific character actor

and star, Hackman has quietly become one of Hollywood’s

most highly regarded performers. If it seems as if the actor has

always been middle-aged, it’s because he didn’t emerge as a

star until he was nearly 40 years old. Despite a haggard, every-

man appearance—or rather because of it—he has been Holly-

wood’s actor of choice in a wide variety of films for more than

three decades. Though he hasn’t been in a great many box-

office blockbusters, even in commercial failures he wins the

plaudits of critics because he plays his roles so skillfully.

Hackman grew up in a lower–middle-class household in

Illinois and quit school when he was 16 to join the marines.

After his stint in the service, he spent years doing everything

from driving trucks to selling shoes before eventually settling

into a vagabond existence working as an assistant director for

a series of small TV stations. Meanwhile, Hackman had been

nurturing his dream of acting. He had obviously seen the tal-

ent on many a local TV show and had been unimpressed.

In his early thirties, long after most aspiring actors have

given up their show business quests, Hackman decided to take

the performing plunge. He studied at the famous Pasadena

Playhouse, where he and fellow student

DUSTIN HOFFMAN

were voted “least likely to succeed.” Undaunted, he went to

New York to try to break into the theater. Thanks to his unac-

torish looks, he soon found modest success in small Off-

Broadway productions and in television, eventually leading to

a starring role in Any Wednesday on Broadway in 1964.

His good reviews in the hit comedy brought the offer of a

small role in Lilith (1964). It was his first important film role

(his movie debut was in a tiny role in Mad Dog Coll, 1961).

Other small character parts followed in films such as Hawaii

(1966) and First to Fight (1967). The big breakthrough, how-

ever, came when

WARREN BEATTY

, who had starred in Lilith,

chose Hackman to play his brother, Buck, in

BONNIE AND

CLYDE

(1967). The controversial film was a hit that boosted

the careers of a great many people, and Hackman garnered a

nomination as Best Supporting Actor for his performance.

Hackman had emerged as a legitimate character actor,

but he had yet to achieve star status. After working in support

of such luminaries as

ROBERT REDFORD

in Downhill Racer

(1969) and

BURT LANCASTER

in The Gypsy Moths (1969), he

was given a rare costarring role with

MELVYN DOUGLAS

in I

Never Sang for My Father (1970). The critics raved about

Hackman’s complex performance, and he was honored yet

again with an Oscar nomination as Best Supporting Actor.

Finally, in 1971, when he played obsessed, uncouth New

York cop “Popeye” Doyle in The French Connection, every-

thing fell into place. The movie was a smash with both crit-

ics and filmgoers and, suddenly, at the age of 40. Hackman

had become a star and the recipient of an Oscar as Best Actor.

He had found the secret of his future success: Play both

heroes and villains as vulnerable, human characters.

After The French Connection, Hackman’s career in the

early 1970s consisted mostly of good roles in good films that

did not fare well with anyone but the critics. The all-star dis-

aster film The Poseidon Adventure (1972) aside, he starred in

such highly regarded movies as Michael Ritchie’s Prime Cut

(1972), Scarecrow (1973), and Francis Ford Coppola’s post-

Godfather masterpiece, The Conversation (1974). Despite good

notices, however, Hackman was in need of a hit. He went

back to the well to recreate Popeye Doyle in French Connec-

tion II (1975), which proved to be a success.

Unfortunately, the second half of the 1970s became a rel-

ative wasteland for Hackman. Except for Night Moves (1975),

a good movie that failed at the box office, most of his other

vehicles were often poor films that were also big commercial

losers. By the end of the decade he was playing Lex Luthor

in Superman (1978) and Superman II (1980).

In the early 1980s Hackman starred with Barbra

Streisand in the little-known but wonderful comedy All Night

183

H

Long (1981). Again, he was well reviewed, but the film went

nowhere. Finally, in 1983, Hackman fired up the public in

one of the first Vietnam-related movies, Uncommon Valor

(1983), which became a sleeper hit. Since then, whether suc-

cessful or not, either his films or his performances (or both)

have generally been critically acclaimed. With a prodigious

output during the mid- to late 1980s, he delighted filmgoers

with brilliant characterizations in films as varied as Under Fire

(1983), Misunderstood (1984), Twice in a Lifetime (1985),

Hoosiers (1986), Bat 21 (1988), Another Woman (1988), Missis-

sippi Burning (1988), and The Package (1989).

Hackman’s standout role of the 1990s was as Little Bill

Daggett in

CLINT EASTWOOD

’s revisionist, postmodern

western Unforgiven (1992). Little Bill was the sheriff of Big

Whiskey, intent upon brutalizing any gunman who might

venture into his jurisdiction; he was equally concerned about

building himself a house, but he is not a proper carpenter or

sheriff. There is black humor in his failures on both counts.

In The Quick and the Dead (1995), he plays another lawman

named Herod, the archvillain who runs a town called

Redemption in a film that overflows with allegory.

Some other villainous roles include those in The Firm

(1993), that of a corrupt lawyer; Absolute Power (1997), that of

a lecherous, murderous U.S. president; and The Chamber

(1996), that of a white supremacist charged with murder. In

Under Suspicion (2000), he played a lawyer accused of the rape

and murder of two 12-year-old girls. In Heartbreakers (2001),

he plays a wheezing tobacco tycoon who is likely to become

a murder victim.

Hackman has also fallen into a number of military roles.

In Crimson Tide (1995), he played the commander of the sub-

marine USS Alabama who clashes with

DENZEL WASHING

-

TON

over an order to fire the sub’s missiles. In Behind Enemy

Lines (2001), a similar kind of conflict exists between the inex-

perienced young soldier (Owen C. Wilson) and Hackman as

an experienced admiral who wants everything by the book.

Another phase of leadership was in The Replacements (2000), in

which Hackman played a professional football coach.

Hackman also revealed a flair for comedy in The Birdcage

(1996), playing an obtuse right-wing senator whose daughter

is about to marry the son of a gay nightclub owner (

ROBIN

WILLIAMS

). In The Royal Tenenbaums (2002), he played a self-

ish, disbarred attorney attempting to reconcile himself with

his dysfunctional family. In 2003 he played another sinister

attorney in Runaway Jury. Of the more than 75 movies Hack-

man has made, six have grossed more than $100 million.

Hanks, Tom (1956– ) An actor specializing in comedy

who became one of the great young talents of the 1980s. Com-

pared to the likes of

JAMES STEWART

and

JACK LEMMON

,

Hanks is an everyman with whom audiences can easily identify.

HANKS, TOM

184

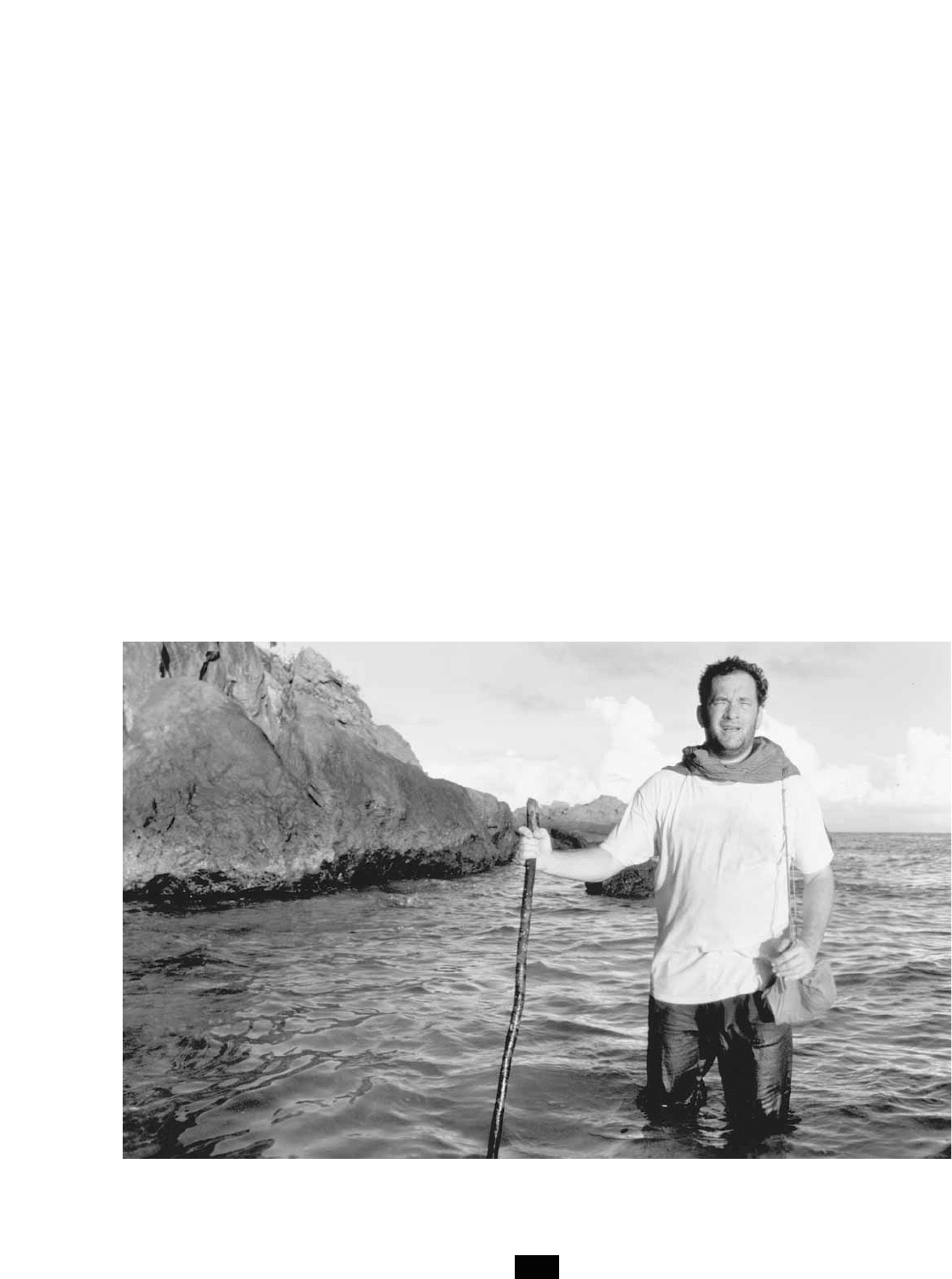

Tom Hanks in Cast Away (2000) (PHOTO COURTESY TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX AND DREAMWORKS)

A gifted light comedian, he can break your heart just as easily

as make you laugh. Good looking in a boyish, unthreatening

way, he has starred in an average of two movies per year since

1984, when he made his film debut in the hit comedy Splash.

Hanks began his acting career as an intern at the Great

Lakes Shakespeare Festival in Cleveland, Ohio, acting in

such plays as The Taming of the Shrew and The Two Gentlemen

of Verona. After brief stints on the stage in both New York and

Los Angeles, he won a starring role in the ABC-TV sitcom

Bosom Buddies, which ran for two years in the early 1980s.

After scoring in Splash, a film that earned more than $60

million, Hanks went on to star in a series of movies that were

extremely variable in both their quality and their box-office

appeal. Though Bachelor Party (1984) earned $40 million, The

Man with One Red Shoe (1985) and Every Time We Say Good-

bye (1986) were box-office failures. Volunteers (1985) and The

Money Pit (1986) both found a modest following, but the film

that got the attention of both the critics and the paying pub-

lic was Nothing in Common (1986), which was the first movie

that showed Hanks capable of reaching deeper, richer emo-

tions underneath his comic persona.

During this period of growth, Hanks often worked with

other strong comic performers, such as John Candy in Volun-

teers, Jackie Gleason in Nothing in Common, and

DAN

AYKROYD

in Dragnet (1987). When given the opportunity to

carry a major motion picture on his own shoulders, he did

not disappoint. After

ROBERT DE NIRO

could not settle on

contractual terms to play Josh Baskin in Big (1988), the role

fell to Hanks, and it brought him both a blockbuster hit that

earned more than $100 million and his first Academy Award

nomination for Best Actor. In that same year, he electrified

the critics with his dazzling performance as a self-destructive

stand-up comedian in Punchline. Unfortunately, the movie

was not the commercial success its producer (and costar)

SALLY FIELD

had hoped it would be. Equally disappointing

for critics was Burbs (1989), but Hanks continued to impress

even when his films didn’t quite match his talent.

The same could be said for his next four films, Turner and

Hooch (1989), Joe Versus the Volcano (1990), Bonfire of the Van-

ities (1990), and Radio Flyer (1992). Better and more popular

features would follow, starting with A League of Their Own

(1992) in which he played a drunken baseball has-been hired

to manage a women’s baseball team. His next picture, with

MEG RYAN

, who was first cast with him in Joe Versus the Vol-

cano, was Sleepless in Seattle (1993), perhaps the most success-

ful romantic comedy of the decade. The two would reprise

their romantic chemistry in the comedy You’ve Got Mail

(1998), based on The Shop around the Corner (1940).

To balance such performances, Hanks starred in 1993 as

a lawyer afflicted with AIDS in Philadelphia (with

DENZEL

WASHINGTON

). This required some courage because other

actors who had played homosexuals had their careers

destroyed as a consequence, but Hanks survived the role

unscathed, perhaps because of what he describes as his “like-

ability-charming factor.” For his performance, Hanks earned

his first Oscar, as well as a Golden Globe Award.

Another courageous role was that of the mentally handi-

capped Forrest Gump in the film directed by

ROBERT

ZEMECKIS

in 1994. As a result of this role, Hanks won back-to-

back Oscars, matching

SPENCER TRACY

’s achievement in 1937

and 1938, the only other actor to be so recognized to date.

Hanks had always wanted to play an astronaut and was

therefore attracted to the role of Jim Lovell in Apollo 13

(1995), another box-office success, grossing $172 million. In

1996 Hanks tried his hand at writing, directing, and produc-

ing, with That Thing You Do, a pleasant movie that covered its

costs but fell short of his other successes. He returned to a

patriotic role in

STEVEN SPIELBERG

’s Saving Private Ryan,

one of the top-grossing films of 1998. (It made $190 million

in comparison to the $356 million made by Forrest Gump,

Hanks’s most successful film.) Hanks was less successful crit-

ically and financially with Cast Away (2000), though the film

earned $109 million and Hanks earned a Best Actor Academy

Award nomination. Some critics were disappointed by this

shipwreck movie with philosophical issues that were never

quite resolved. Audiences loving Hanks did not seem to

notice, however. In Catch Me If You Can (2002), Hanks plays

a nerdy FBI agent hot on the trail of a young con artist played

by

LEONARDO DICAPRIO

and was directed by the ever-popu-

lar Steven Spielberg.

Harlow, Jean (1911–1937) Previously in films, the

vamp usually had dark hair, while the “good” girl was blonde,

but Harlow added a new dimension: Her platinum blonde

hair was so unique and (for the 1930s) her gowns so low-cut

that the expression “blonde bombshell” was coined to

describe her. She was modern, vulgar, and wonderfully funny.

Here was a woman who seemed to want sex as much as a man

does. Harlow brought to the movies a healthy sex appeal that

was both shocking and liberating in its time.

Born Harlean Carpenter to a middle-class family, she

ran away from home to get married at 16. After the mar-

riage failed, she went to Hollywood and worked as an extra,

eventually winning a small part in Moran of the Marines

(1928). Other tiny roles followed, most notably in The Love

Parade (1929).

Nothing came of her work until

HOWARD HUGHES

got a

glimpse of her. Hughes wanted her for Hell’s Angels (1930),

his epic air-war movie that had been two years in the making

but had to be reshot because of the advent of sound. Hughes,

always quick to spot a beauty, saw her potential and signed

her to star in his film as the woman who comes between the

two heroes.

Hell’s Angels was a big hit, partly because of the remark-

able aerial display in the movie and partly because Harlow

was so sexy. Hughes had her under a long-term contract and

proceeded to loan her to other studios for lead roles, notably

to Warner Bros. for Public Enemy (1931). She was also loaned

to Columbia, where she starred in

FRANK CAPRA

’s Platinum

Blonde (1931), a movie clearly titled to best take advantage of

her peculiar hair color.

Hughes finally sold her contract to MGM for $60,000.

She appeared in two MGM films without causing much of a

ripple until Red Dust (1932) with

CLARK GABLE

. The two

stars ignited sexual fires, making the rather daring movie a

HARLOW, JEAN

185

blockbuster hit. Harlow and Gable were a hot team; they

were paired together a total of five times in just six years, and

all of their films drew big crowds.

After Red Dust, Harlow was the Hollywood sex goddess,

and, as such, she was a perfect foil for the purposefully stuffy

cast in MGM’s all-star film Dinner at Eight (1933), just as she

was the perfect victim in the aptly titled Bombshell (1933).

She could play tough (Riff Raff, 1935) or she could play

funny (Suzy, 1936). But no matter what she played, the slinky

star had one hit after another. There was no reason to believe

she might not have an extremely long career. Tragedy struck,

however, when Harlow was only 26 years old. She had been

filming Saratoga (1937) when she fell ill and then suddenly

died of uremic poisoning. The movie was finished with a

double and went on to become a great hit precisely because

it was the sexy star’s last movie.

See also

SEX SYMBOLS

:

FEMALE

.

Harris, Ed (1950– ) For most of his film career Ed

Harris has not been a leading man, but in his secondary roles

he has had outstanding success, having received two Oscar

nominations as Best Supporting Actor. He was also nomi-

nated for an Oscar as Best Actor in Pollock (2000), a film that

he also directed, has also received an Obie, and has been

nominated for a Tony for his theatrical performances. He has

also won awards for his television work.

Born in Englewood, New Jersey, he enrolled at Colum-

bia University but transferred to the University of Oklahoma

when his family moved to that state. At Oklahoma he studied

acting, and then he went to Los Angeles, where he attended

the California Institute of the Arts. He made his film debut

in Coma (1978) and has appeared in at least one film every

year since then.

During the 1980s, he was in about 20 films, some of them

made for television. Among the best were Under Fire and The

Right Stuff (both 1983) and Sweet Dreams (1985), the Patsy

Cline biopic, in which he played the singer’s husband. In the

role, he was a hard-drinking womanizer who could not deal

with his wife’s success.

In the 1990s his roles and his films improved dramati-

cally. He played a detective in China Moon (1991) and in

Absolute Power (1997) and a sheriff in Needful Things (1993);

he played on the other side of the law in Just Cause (1994) as

an incarcerated serial killer and State of Grace (1990) as a gang

leader. He also had good roles in Nixon and Apollo 13 (both

1995), Glengarry Glen Ross (1992), and The Firm (1993). In

The Rock (1996) he was a decorated general who leads some

of his former soldiers to capture Alcatraz; he was appropri-

ately fanatic and vicious.

The Truman Show (1998) allowed him to exercise his

authoritarian skills in the role of Christof, the producer and

director of the reality television show in which

JIM CARREY

unwittingly stars. Because of the way he is photographed, he

appears as a kind of god overseeing and controlling his own

universe. For his performance, he was nominated for a Best

Supporting Actor Oscar and won a Golden Globe and the

National Board of Review award for Best Supporting Actor.

His leading roles during the decade were in Running Mates

(1992) as a presidential candidate, replete with girlfriend,

who has a past, and in Stepmom (1998), as a divorced dad with

two kids.

HARRIS, ED

186

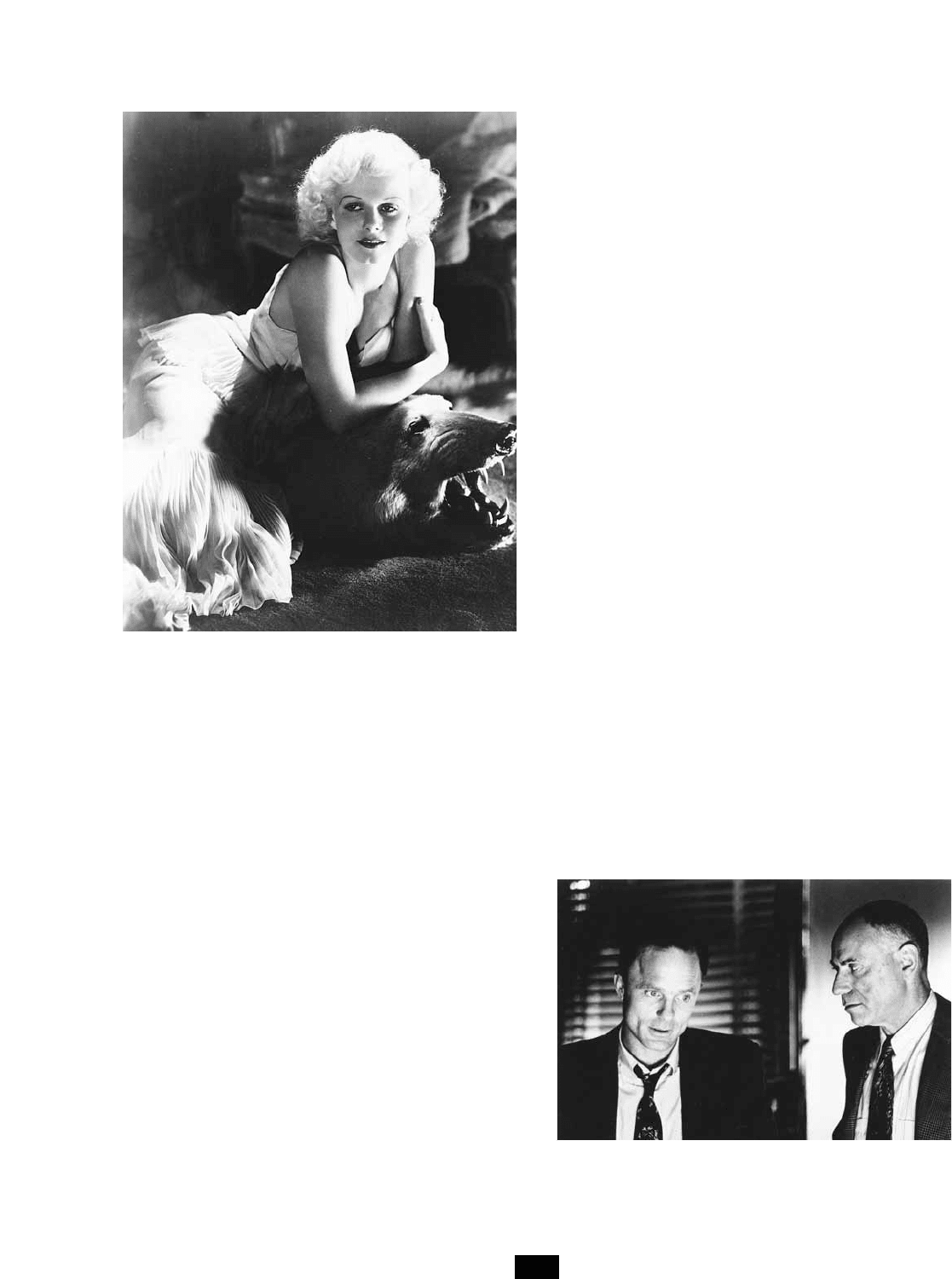

Jean Harlow was the sound era’s first major sex symbol. She

brought an earthiness to the screen to which audiences

responded—especially when she played her roles for laughs.

(PHOTO COURTESY OF THE SIEGEL COLLECTION)

Ed Harris (left) in Glengarry Glen Ross (1992) (PHOTO

COURTESY NEW LINE CINEMA)

In 2000, he produced and directed Pollock, a biopic about

the painter Jackson Pollock, an alcoholic and tormented

genius. In the film, Harris runs the gamut of emotions and

expresses the self-destructive urges that led to Pollock’s

death. He was again nominated for an Oscar, this time for

Best Actor. In 2001, he played the imaginary federal agent of

John Nash’s hallucinations in the award-winning A Beautiful

Mind and in 2003 was again nominated for Best Supporting

Actor Oscar and Golden Globe awards in the critically

acclaimed The Hours (2002).

Hart, William S. (1870–1946) There were quite a few

silent western movie stars, but William S. Hart was the first to

bring a sense of authenticity to the genre.

Hart grew up in the West, counting many Sioux Indians

among his childhood friends. He hated the misrepresentation

of the West in the early one- and two-reelers that had

become so vastly popular. After touring as a stage actor, he

went to Hollywood to make the kinds of westerns he thought

ought to be made.

He played the bad guy in his first film appearance. The

movie was a two-reeler titled His Hour of Manhood (1914). He

was already 44 years old but, with rugged good looks and a

seriousness of purpose that bespoke integrity, it didn’t take

him long to catch on. In the same year as his debut, he starred

in his first film, The Bargain (1914).

One of his best early movies was Hell’s Hinges (1916), and

audiences responded to it (and most of the rest of his films)

because of the gritty details, the credible action, and Hart’s

no-nonsense persona (although he sometimes looked as grim

as Buster Keaton’s old stone face). Hart’s dedication to his

subject matter led him not only to star in his own films but

also often to write, direct, and produce them. Except for

CLINT EASTWOOD

, Hart was the last major western star to

take such complete control of his movies.

Hart was the number-one western star in the late teens

and early 1920s. By the mid-1920s, his popularity began to

fade. He decided to make one last movie, Tumbleweeds (1925),

and it was his masterpiece. The movie was a major hit, but

Hart, discouraged with the movie business and the general

direction of the western, decided to retire. His last film

appearance was in 1939 when he filmed an introduction for

the reissue of Tumbleweeds. He had an excellent speaking

voice and surely could have had a talkie career, but Hart had

left the business while he was still on top and he never

expressed any regrets.

See also

WESTERNS

.

Hathaway, Henry (1898–1985) He was a dependable,

efficient, and unpretentious director of mostly “

A

”

MOVIE

s

for more than 40 years during the sound era. Though never

in the same league as such directors as

JOHN FORD

and

HOWARD HAWKS

, Hathaway brought a direct and lively com-

petence to large-scale action films (especially westerns) and a

gritty, no-nonsense style to mystery/suspense/crime films.

Born into a theatrical family in California (his father was

a theater manager, and his mother was an actress), Hathaway

began his career in the movies as a child actor in 1908,

appearing in more than 400 one- and two-reelers, many of

them for director

ALLAN DWAN

. After a stint in the army

during World War I, Hathaway returned to Hollywood and

began to work behind the camera as a property man and later

as an assistant director for the likes of Paul Bern,

JOSEF VON

STERNBERG

, and Victor Fleming.

He began his directorial career with a string of

RAN

-

DOLPH SCOTT

“B” movie westerns in 1932, the first of

which was Heritage of the Desert. His big break came in

1935 when he was assigned to direct

GARY COOPER

in The

Lives of a Bengal Lancer. It was the first major Hollywood

movie about India, and Hathaway’s grasp of the difficult

project and his solid storytelling abilities garnered him not

only a big box-office success but also the respect of his

bosses at Paramount.

Hathaway established a well-earned reputation for deal-

ing with unusual or difficult films. He had a way of keeping

his stories on track despite all the peripheral razzmatazz. He

demonstrated his ability time and again in films such as the

bizarre romantic fantasy Peter Ibbetson (1935) and the first of

many Hollywood pseudo-documentary thrillers, The House

on 92nd Street (1945). He directed the untried

MARILYN

HATHAWAY, HENRY

187

Silent western star William S. Hart brought a gritty realism

to his films, but he was not without a sense of humor. That

old chestnut about cowboys kissing their horses can finally

be put to rest: Clearly, it was the horses who did the kissing.

(PHOTO COURTESY OF THE SIEGEL COLLECTION)