Snoman R. Dance Music Manual: Tools, Toys, and Techniques

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

PART 1

Technology and Theory

204

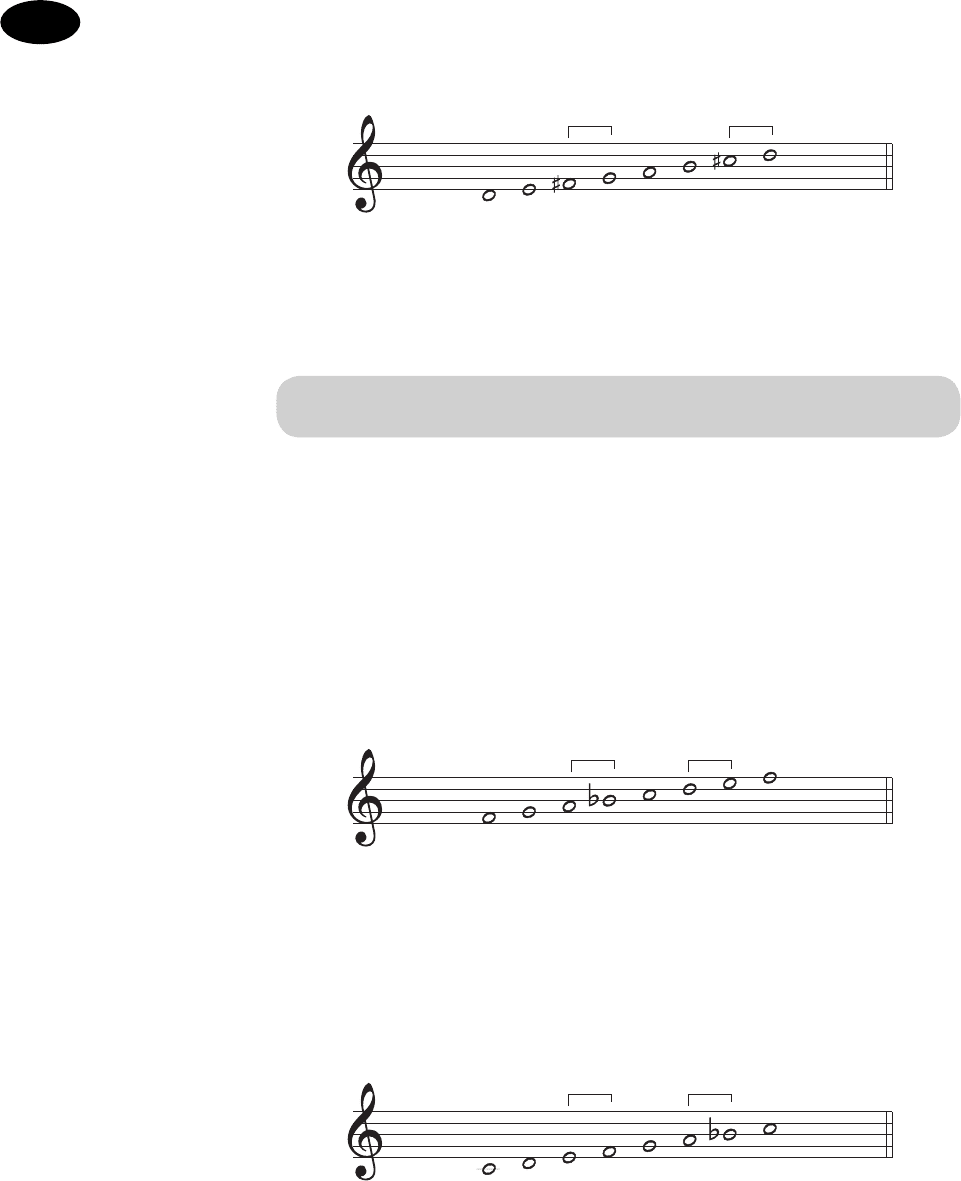

Semitone Semitone

F# B

DC#DE

AG

Say that you’ve written a melody in C and you pitch it up 5 semitones to F.

This essentially means that F becomes the root note and the pattern of tones

changes to the Lydian mode spacing:

Tone – Tone – Tone – Semitone – Tone – Tone – Semitone

Again, this looks fi ne on paper, but there’s a problem with simply pitching it

up to F because if the original riff in the key of C is simply pitched up to F, any

note that was originally an F would become an A# and any note that was origi-

nally an E would become an A. In other words, F has become A sharp. In this

event, the black keys are no longer referred to as sharps; instead they’re referred

to as fl ats, which are identifi ed by a ‘b ’ , as in B b .

Because the black keys on the keyboard can be either sharps ( #) or fl ats ( b ),

depending on the key of the song or melody, they are sometimes referred to

as ‘enharmonic equivalents ’. Of course, depending on where the scale is con-

structed the black keys will be sharp or fl at, but they can never be a mixture of

the two.

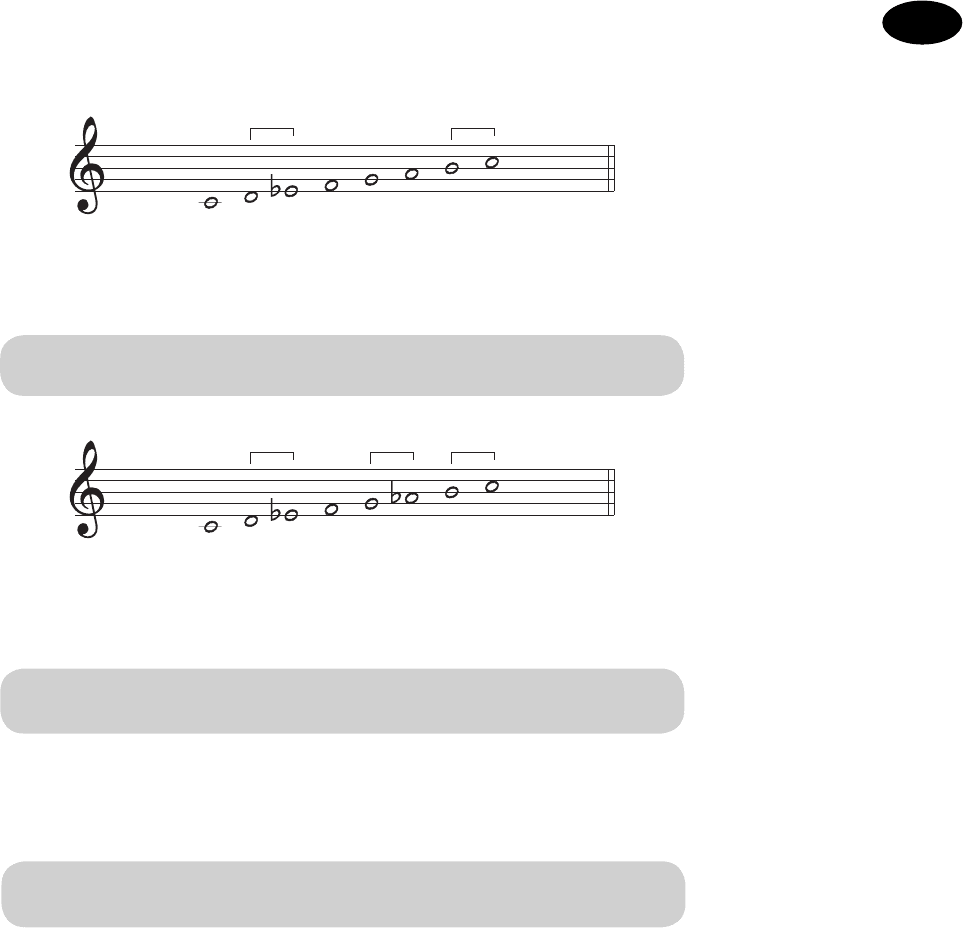

Semitone Semitone

FBb

GEDA

CF

MINOR SCALES

Along with the major scale, there are three minor scales consisting of the ‘har-

monic’ minor, ‘natural’ minor and the ‘melodic’ minor. These are based around

exactly the same principles as the major scale, with the only difference being

the order of the tones and semitones. As a result , each of these minor scales

has a unique pattern associated with it.

Semitone Semitone

F

DCE

GBAC

Music Theory

CHAPTER 10

205

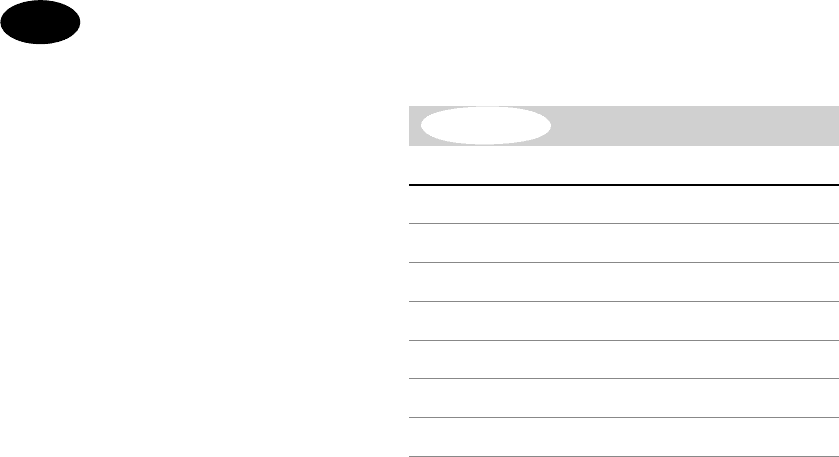

Semitone Semitone

FDCE

ABGC

The harmonic minor scale has semitones at the scale degrees of 2 –3, 5 –6 and

7–8. Thus they all follow the pattern:

Tone – Semitone – Tone – Tone – Semitone – Tone – Semitone – Semitone

Semitone SemitoneSemitone

FDCE ABGC

The natural minor scale has semitones at the scale degrees of 2 –3 and 5 –6.

Thus they all follow the pattern:

Tone – Semitone – Tone – Tone – Semitone – Tone – Tone

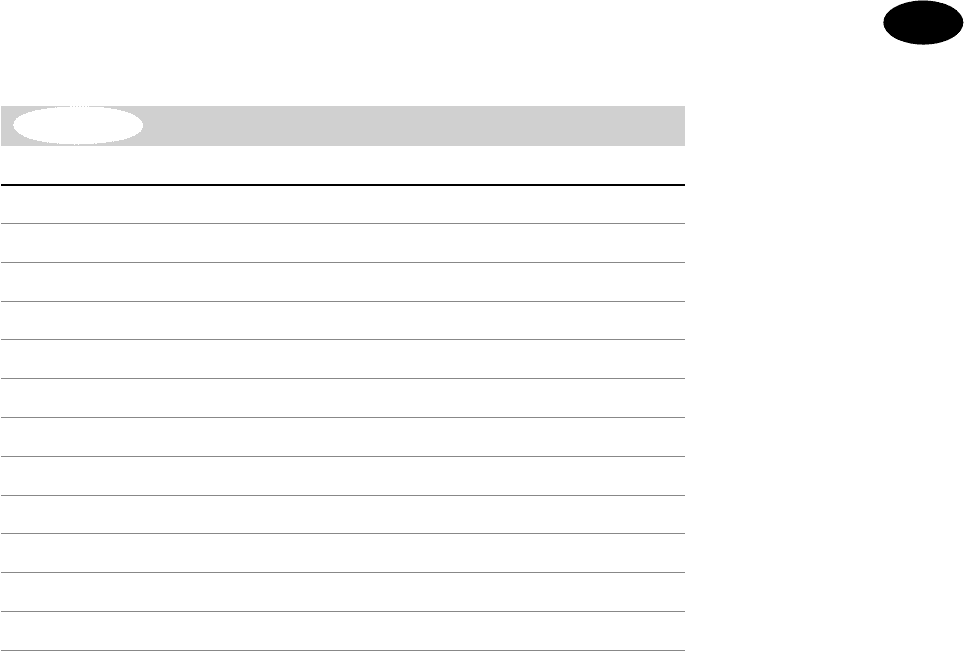

The melodic minor has semitones at the scale degrees of 2 –3 and 7 –8 when

ascending, but reverts back to the natural minor when descending. Thus they

will all follow the pattern of:

Tone – Semitone – Tone – Tone – Tone – Tone – Semitone

Generally speaking, the harmonic minor scale is used to create basic minor

chord structures that are used to harmonize with riffs or melodies that are writ-

ten using the melodic and natural minor scales. Every major key will have a

related minor and every minor will have a related major, but this doesn’t mean

that the closest relationship to the key of C major, for example, would be C

minor. Instead, the major and minor keys that have the most notes in common

with one another are most closely related.

For instance, the closest related minor to C major is A minor because it has the

most notes in common. As a guideline, you can defi ne a minor from a major by

building it from the sixth degree of the scale; a major can be constructed from the

PART 1

Technology and Theory

206

minor scale by building from the third degree of the minor scale. The structures

of major and minor scales are often referred to as modes. Rather than describing

a melody or song by its key, it’s usual to use its modal term ( Table 10.2 ).

Modes are incredibly important to grasp because they will often determine the

emotion the music conveys. This isn’t due to some scientifi c reasoning but because

it’s our instinctive reaction to subconsciously reference everything we do, hear or

see with past events. Indeed, it’s impossible for us to listen to a piece of music

without subconsciously referencing it against every other piece we’ve ever heard.

This is why we may feel immediately attracted to or feel at ‘home’ with some

records but not with others. For instance, most dance music is written in the

major Ionian mode. If it were written in the minor Aeolian mode the mood

would seem much more serious.

CHORDS

There’s much more to music than understanding the various scales and modes

since no matter what key you play if only one note was played at a time it

would be rather boring to listen to. Indeed, it’s the interaction between numer-

ous notes played simultaneously that provides music with its real interest.

More than one note played simultaneously is referred to as a harmony, and the

difference in the pitch between the two played notes is known as the ‘interval ’.

Intervals can be anything from just one semitone to above an octave apart. It

should go without saying that the sonic quality of a sound varies and multi-

plies with each additional note that’s played.

Each different interval is given its own name. For example, harmonies that

utilize three or more notes are known as chords. The size of these intervals

infl uence the ‘feel’ of the chord being played and some intervals will create a

more pleasing sound than others. Intervals that produce a pleasing sound are

called consonant chords, while those less pleasing are called dissonant chords.

Modes

Key Name Mode

C Tonic Major (Ionian)

D Supertonic Dorian

E Mediant Phrygian

F Subdominant Lydian

G Dominant Mixolydian

A Submediant Minor (Aeolian)

B Subtonic Locrian

Table 10.2

Music Theory

CHAPTER 10

207

The combination of the two together can be used to create tension in music,

so each is of equal importance when you are writing a track. Indeed, creating

a track using nothing but consonant chords results in a track that sounds quite

insipid, while creating a track with only dissonant chords will make the music

sound unnatural. The two must be mixed together sympathetically to create the

right amount of tension and release. To help clarify this, Table 10.3 shows the

relationship between consonant and dissonant chords, and the interval names

over an octave.

Intervals of more than 12 semitones that span the octave have a somewhat dif-

ferent effect.

Nevertheless, to better understand how chords are constructed we need to

jump back to the beginning of the chapter and look at the layout of C major.

Using this chart we can look at the simplest chord structure – the triad. As the

name suggests, this consists of three notes and is constructed from the fi rst,

third and fi fth degree notes from the major scale that forms the root note of

the chord.

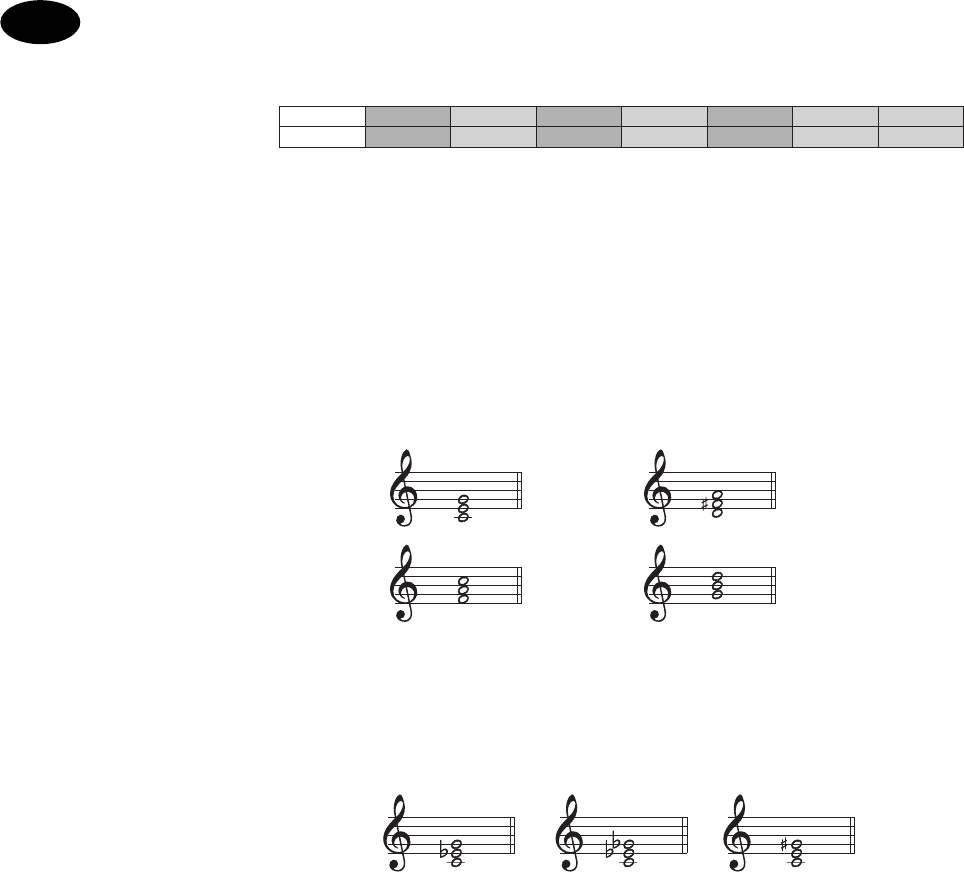

You can see from Figure 10.2 that the root note of the C major scale is C, which

corresponds to the fi rst degree. To create the C major triad, the third and fi fth

degree notes must be added, giving us the chord C –E–G (or fi rst, third and fi fth

Interval Relationships

Interval Semitones Apart Description

Unison Same note Strongly consonant

Minor second One Strongly dissonant

Major second Two Mildly dissonant

Minor third Three Strongly consonant

Major third Four Strongly consonant

Perfect fourth Five Consonant or dissonant

Tritone Six Mildly dissonant

Perfect fi fth Seven Strongly consonant

Minor sixth Eight Mildly consonant

Major sixth Nine Consonant

Minor seventh Ten Mildly dissonant

Major seventh Eleven Dissonant

Table 10.3

PART 1

Technology and Theory

208

degree). This major triad is the most basic and common form of chord and is

often referred to as ‘CMaj’.

As before, this chord template can be moved to any note of the scale; thus there

is a whole scale of chords available. For example, a chord from the root key of G

would consist of the notes G –B–D. Similarly a triad in the root key of F would

result in F –A–C. This also means that in a triad with a root key of D, E, A or B, the

third tone will always be a sharp.

Pitch C D E F G A B

Degree 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

FIGURE 10.2

Grid of the C major scale

C major D major

F major G majo

r

In addition, there are three variations to the major triad chord: the ‘minor’,

‘ diminished’ and ‘augmented’ triads. Each of these works on a similar principle

as the major triad, with the difference that for the minor and diminished triad,

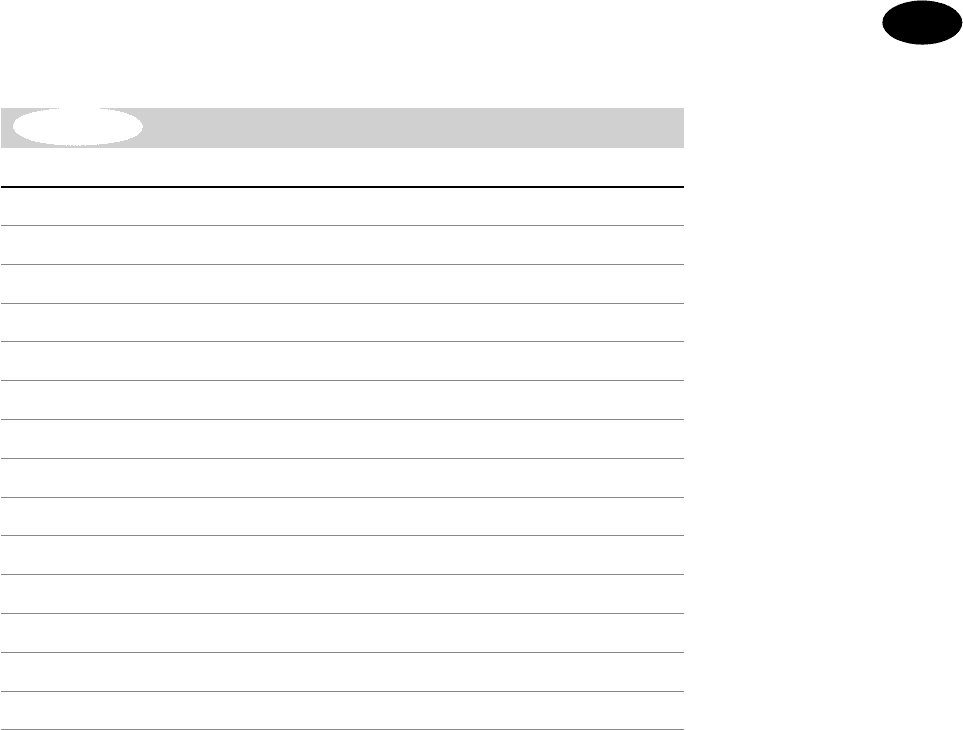

the third tone is lowered by one semitone (Figure 10.3) .

Minor Diminished Augmented

FIGURE 10.3

Variations to the major

triad

For instance, taking the major triad C –E–G from the root key of C and lowering

the third tone gives us the notes in the minor triad C –Eb – G. For a diminished

triad we do the same again, but this time both the third and fi fth tone are low-

ered, resulting in C –Eb – Gb. Finally, to create an augmented triad we increase

the fi fth note by a semitone, producing C –E–G#. These and other basic chord

groups are shown in Table 10.4 .

So, to recap:

■ To create a major triad, take the fi rst-, third- and fi fth-degree notes of the

scale.

■ To create a minor triad, lower the third degree by a semitone.

Music Theory

CHAPTER 10

209

■ To create a diminished triad, lower the third and fi fth degrees by a

semitone.

■ To create an augmented triad, raise the fi fth degree by a semitone.

These examples in Table 10.4 show single chords. In a musical context, the

transition between these chords is what gives music its unique character and

sense of movement. To introduce this sense of movement, the centre note of

the chord (the third degree) is inverted or moved as the chords progress. This

means that while both the fi rst and fi fth degrees of the chord remain 7 semi-

tones apart, the third often moves around to create intervals. For instance, mov-

ing the third degree up a semitone creates an interval known as a major third,

whereas if it were positioned or moved to 3 semitones above the root note, it

would become a minor third. Inversions are created in much the same way and

provide a great way for the chords to move from one to the next.

Inversions are created when one of the notes is moved by a melodically suit-

able degree. How this is achieved is largely down to experimentation. As an

example, if we are writing a tune using the chord of C, we can transpose the

fi rst degree (C) up an octave so that the E becomes the root note, to create

Basic Chord Groups

Chord/Root Major Minor Diminished Augmented

C C–E–G

C –Eb – G C–Eb – Gb

C –E–G#

D D–F#–A D–F–A

D –F–Ab

D –F#–A#

E E–G#–B E–G–B E–G–Bb E–G#–C

F F–A–C F–Ab–C F–Ab–B F–A–C#

G G–B–D G–Bb–D G–Bb–Db G–B–D#

A A–C#–E A–C–E A–C–Eb A–C#–F

B B–D#–F# B–D–F# B–D–F B–D#–G

C# (enharmonic Db) C#–E# (F) –G# C#–E–G# C#–E–G C#–E# (F) –A

Db Db–F–Ab Db–E–Ab Db–E–G Db–F–A

Eb Eb–G–Bb Eb–Gb–Bb Eb–Gb–A Eb–G–B

F# (enharmonic Gb) F# A# C# F#–A–C# F#–A–C F#–A#–D

Gb Gb–Bb–Db Gb–A–Db Gb–A–C Gb–Bb–D

Ab Ab–C–Eb Ab–B–Eb Ab–B–D Ab–C–E

Bb Bb–D–F Bb–Db–F Bb–Db–E Bb–D–F#

Table 10.4

PART 1

Technology and Theory

210

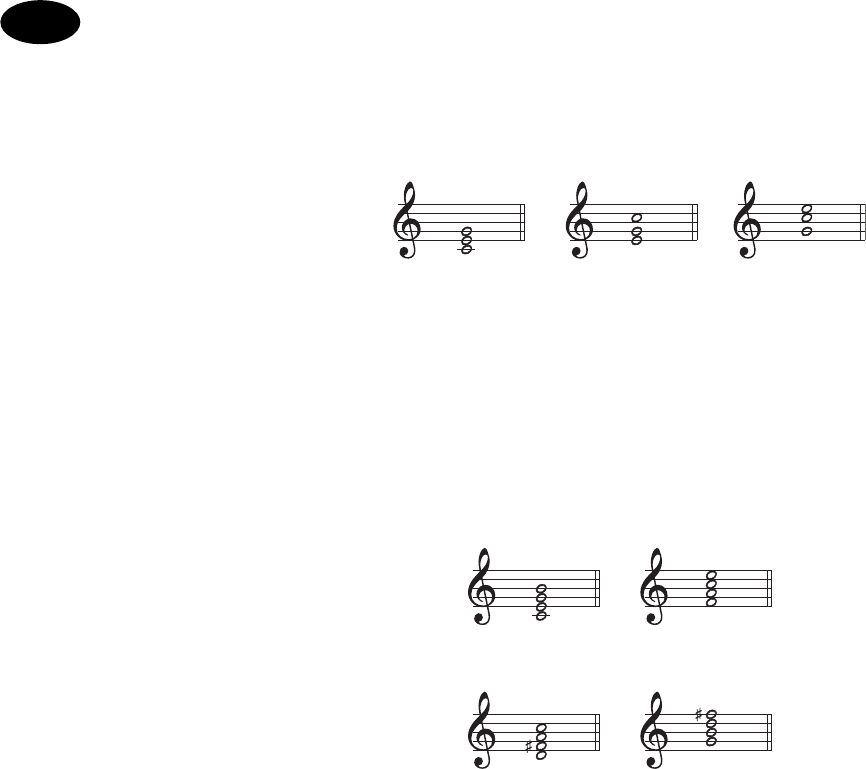

what’s called a ‘fi rst inversion ’. Next, we can transpose the E up an octave, leav-

ing the G as the root. This creates a second inversion .

C maj First

Second

This kind of progression is especially suitable for pads or strings that need to

smoothly change as the track progresses without capturing too much unwanted

attention. That said, any movement of any degree within the chord might be used

to create chord progressions, which, as mentioned, is down to experimentation.

Simple triad chords, such as those shown in Table 10.4 , are only the beginning. The

next step up is to add another note, creating a four-note chord. The most commonly

used four-note chord sequences extend the major triad by introducing a seventh

degree note, which results in a 1 –3–5–7 degree pattern ( C–E–G–B in C major).

CF

D G

It is, however, uncommon for four-note chords to be employed in dance music

because major and minor sevenths are more synonymous with Jazz music. That

said, you should experiment with different chord progressions as the basis for

musical harmony. For those who still feel a little unsure about the construction

of chords, listed below are some popular chords:

C –Eb–G–A

C –Eb–G–D

C –Eb–G–Bb–F

C –Eb–G–Bb–D

C –Eb–G–Bb–D–F–A

C –Eb–G–B–D

C –Eb–F#–Bb–D

C –Eb–F#

C –Eb–F#–A–B

C –E–G#–B

Music Theory

CHAPTER 10

211

C –E–G–B

C –E–G#

C –F–G–Bb–C#–A

C –F–G

C –F–G–Bb–D

C –E–G–B–D

C –E–G–B–D–F#

C –E–F#–Bb

C –E–G#–Bb

C –E–G–Bb–C

C –E–F#–Bb–C#

C –E–G#–Bb–C#

C –E–G–Bb–D–F#

C –E–G–Bb–Eb–F#

C –E–G–Bb–C#–A

C –E–G–A

C –E–G–D

C –E–G–Bb–D

C –Eb–G–A–D

C –Eb–G–Bb

C –Eb–G–Bb–A

C –Eb–G–Bb–D–F

C –Eb–G–B

C –Eb–F#–Bb

C –Eb–F#–Bb–D–F

C –Eb–F#–A

C –E–F#–B

C –E–G–B–F#

C –E–G–B–A

C –F–G–Bb–C#

C –F–F#–B

C –F–G–Bb

C –F–G–Bb–D–A

C –E–G–B–D–A

C –E–G–B–D–F#–A

C –E–F#–Bb–D

C –E–G#–Bb–D

C –E–G–Bb–Eb

C –E–Ab–Bb–Eb

C –E–G–Bb–F#

C –E–G–Bb–C#–F#

C –E–F#–Bb–D–A

C –E–G–Bb–D–F#–A

C –E–G–D–A

C –E–G–Bb

C –E–G–Bb–D–A

PART 1

Technology and Theory

212

Once the basic chords are laid down, you can begin to construct a bass line

around them. This is not necessarily how all music is formed, but it is com-

mon practice to derive a chord structure from the bass or melody or vice versa,

and it’s useful to prioritize the instruments in the track in this way. Generally,

whichever instrument is laid down fi rst depends on the genre of music.

While there are no absolute rules to how music is written – or at least aren’t any

as far as I know – it’s best to avoid getting too carried away programming complex

melodies when they don’t form an essential part of the music. Although music

works on the principle of contrast, having too many complicated melodies and

rhythms playing together will not necessarily produce a great track; you’ll probably

end up with a collection of instruments that all are fi ghting to be noticed.

For example, a typical hands in the air trance with big, melodic, synthetic leads

doesn’t require a complex bass melody because the lead is so intricate. The bass

in these tracks is kept very simple. Because of this, it makes sense to work on

the melodic lead fi rst, to avoid putting too much rhythmical energy into the

bass. If you work on the bass fi rst you may make it too melodic and harmoniz-

ing the lead to sit will be much more diffi cult. In our example, it may detract

from the trance lead rather than enhance it.

If, however, you construct the most prominent part of the track fi rst – in this

case the melodic synthesizer motif – it’s likely that you’ll be more conservative

when it comes to the bass. If the chord structure is fashioned fi rst, this problem

does not rear its ugly head because chord structures are relatively simple and

this simplicity will give you the basic ‘key’ from which you can derive both the

melody and bass to suit the genre of music you are writing.

FAMILIARITY

As already discussed, the subconscious reference we apply to everything we

hear is inevitable, so it pays to know the chord progressions that we are all

familiar with. Chord progressions that have never been used before tend to

alienate listeners. Arguably most clubbers want familiar sounds that they’ve

heard a thousand times before and are not interested in originality – an obser-

vation that will undoubtedly stir up some debate. Nevertheless, it’s true to say

that each genre – techno, trance, drum ‘n’ bass, chill out, hip-hop, and house –

is based around same theme. Indeed, whether we choose to accept it or not,

this is how they are categorized into sub genres. This is not to say that you

should attempt to copy other artists but it does raise a number of questions

about originality.

The subject of originality is a multifaceted and thorny issue and often a cause of

heated debate among musicians. Although the fi ner points of musical analysis

are beyond the scope of this book, we can reach some useful conclusions by

looking at it briefl y. L. Bernstein and A. Marx are two people who have made

large discoveries in this area and are often viewed as the founders of musi-

cal analysis. They believed that if any musical piece is taken apart there will

Music Theory

CHAPTER 10

213

be aspects of it that are similar to most other records. Whether this is because

musicians are often infl uenced by somebody else’s style is a subject for debate,

but while the similarities are not immediately obvious to the casual listener,

to the musician these similarities can be used to form the basis of musical

compositions.

We can very roughly summarize their discoveries by examining the musical scale.

As we’ve seen, there are 12 major and 12 minor keys, each of which consists

of eight notes. What’s more, there are three basic major and three basic minor

chords in each key. Thus, sitting at a keyboard and attempting to come up with

an original structure is unlikely. When you do eventually come up with a pro-

gression that you believe sounds ‘right’, it sounds this way because you’ve sub-

consciously recognized the structure from another record.

This is why chord structures can often trigger an emotional response in you. In

fact, in many cases you’ll fi nd that most dance hits have used a series of very

familiar underlying chord progressions. While the decoration around these

progressions may be elaborate and different in many respects, the underlying

harmonic structure is very similar and seldom moves away from a basic three-

chord progression. Whether you wish to follow this train of thought is entirely

up to you, but there’s nothing wrong with forming the bass and melody

around a popular chord structure then removing the chords later on. In fact,

popular chord structures are often a good starting point if inspiration takes a

holiday and you’re left staring at a blank sequencer window.

MUSICAL RELATIONSHIP

It’s vital that the chords, bass and melody of any music style work together

and complement one another. Of these three elements, the most important

relationship is between the bass and the melody, so we’ll examine this fi rst.

Generally, the bass and melody can work together in three possible ways:

parallel, oblique or contrary motion.

Parallel motion is when the bass line follows the same direction as the melody.

This means that when the melody rises in pitch the bass rises too, but it does

not follow it at an exact interval. If both the melody and bass rise by a third

degree, the resulting sound will be too synchronized and ‘programmed’ and

will lose all of its feeling. Rather, if the melody rises by a third and the bass

by a fi fth or alternate thereof, the two instruments will sound like two voices

rather than one. Also, the bass should borrow some aspects from the progres-

sion of the melody but should not play the same riff.

When the melody and bass work together in oblique motion, either the mel-

ody or the bass moves up or down in pitch while the other instrument remains

where it is. When the music is driven by the melody, such as trance, the melody

moves while the bass remains constant. In genres such as house, where the bass

is often quite funky with plenty of movement, the melody remains constant

while the bass dances around it.