The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 13: Republican China 1912-1949, Part 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

CHINA S POSTWAR ECLIPSE 541

There were many possibilities, but none of them put China at the centre

of the stage. At the end of the war, China seemed to occupy a back seat

in the drama of world politics and postwar economic development. For

this state of affairs, events inside China, of course, were in large part to

blame. For the Chinese were never able to establish a unified government

through peaceful means. Civil war erupted as soon as Japan surrendered.

China was thrown into chaos, as the Nationalists waged a desperate

struggle to survive the Communists' challenge.

The theme of international cooperation and Chinese willingness to share

the responsibility for world order was reiterated by Nationalist spokesmen

and the press throughout the immediate postwar

years.

These themes fitted

admirably into the Nationalists' domestic programme. The stress on

international solidarity and cooperation implied that other powers would

assist the Nationalist regime in its task of postwar reconstruction. Such

cooperation would enhance the government's prestige. It was absolutely

essential to preserve the framework of international cooperation, for

otherwise dissident elements in the country might turn to foreigners for

help,

or foreign governments might adopt discordant policies toward

China to the detriment of political unity within the country.

71

The Communists meanwhile feared that big-power cooperation would

primarily benefit the recognized government, now re-established at

Nanking, which would seize the opportunity to stamp out dissidence. For

this reason, it was necessary to emphasize, as Mao Tse-tung and others

did in 194

5,

that international cooperation should aim at promoting a truly

representative government in China. They pushed for the establishment

of a coalition government, and welcomed the mediatory effects of General

George C. Marshall, launched in December 1945 and lasting throughout

1946.

At the same time, however, the Communists feared the possibility

that the United States, Britain, and even the Soviet Union might acquiesce

in Nationalist control of China, and believed it important to consolidate

and expand their bases in Manchuria and North China even as they

supported the theme of international cooperation.

72

In time, as Marshall's

efforts at mediation got nowhere and the civil war intensified, the

Communists

came

openly to denounce the idea of international cooperation

as a mask to conceal America's imperialistic ambitions, and to accuse the

Nationalists of having sacrificed national welfare to those ambitions. The

Nationalists, on their part, would turn more and more exclusively to the

United States for support against the Communists. In the process, the ideal

of China's position as a partner in the world arena would be eclipsed by

71

Cbtmg-jangjib-poo, u Sept., 21 and 25 Nov., 1945.

71

See Okabe's and Nakajima's essays in Yonosuke Nagai and Akira Iriye, eds. The origins of the

Cold War

in

Asia.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

54

2

CHINA'S INTERNATIONAL POSITION

that of its position as a member of one or other of the power blocs which

now divided the once cooperative alliance of the big powers.

The erosion of the theme of international cooperation or, to put it

differently, the origins of the American-Soviet Cold War can best be

understood if one recalls that the wartime collaboration had contained

three elements: the popular front, the democratic alliance, and reintegra-

tionism. The victory over Germany and Japan did much to undermine

the rationale for the popular front, although national leaders continued

to pay lip-service to its underlying principle of anti-fascist struggle. That

formulation was now to be applied to the postwar peace settlement to

ensure the eradication of

Axis

militarism. But it was not sufficient to cope

with new postwar problems, such as atomic weapons and anti-colonialism.

In these and related matters, there was a tendency to revert to the

Anglo-American democratic alliance, with its emphasis on the common

interests and orientations of the Western democracies. In both the United

States and Britain, Anglo-American cooperation, rather than Anglo-

American—Soviet collaboration, re-emerged as the most plausible

framework for postwar policy. In the meantime, the theme of

reintegrationism grew in influence now that reconstruction of war-

devastated lands dominated the concerns of governments. Economic

recovery necessitated massive help by the one country that had retained

and even increased its wealth during the war, the United States; and

American officials avidly formulated principles for regional integration

and development, resumption and expansion of global trade, and

restabilization of world finances. By the end of 1946, certain key themes

had emerged: European economic union, Asian regional development,

German and Japanese reintegration. In their emphasis on German and

Japanese recovery and reintegration, these themes recalled the earlier

policy of appeasement with the same emphasis on the development of a

global network of advanced industrial countries freely exchanging goods

and capital among themselves.

The Cold War, in such

a

context, meant the decline of the popular front

and its overshadowing by the other two themes - Anglo-American

cooperation and reintegrationism (appeasement). Clearly, to the extent

that the popular front had been an anti-fascist conception, its decline and

the re-emergence of appeasement were no accident. For, in a sense, the

Cold War implied the replacement of the US-Soviet-British alliance by a

new coalition among the United States, Britain, Germany and Japan.

Where such developments placed China was quite obvious. To be sure,

the Cold War in the sense of American-Soviet antagonism did not initially

make an impact on Asia. Both Chinese Nationalists and Communists were

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CHINA'S POSTWAR ECLIPSE 543

slow

to

apply that framework

to

their country. The Nationalists continued

to stress the theme of global cooperation

up to at

least 1947,

in

the obvious

belief that

the

framework

of

cooperation among America, Britain, Russia

and China still provided

the

best assurance

for

Asian security

and for

Nationalist survival.

One key to

such cooperation,

of

course,

was

Soviet

adherence

to the

1945 treaty.

73

The

Communists,

for

their part,

had

never

reconciled themselves

to

that treaty which provided

for

Moscow's

recognition

of the

Kuomintang regime

as the

legitimate government

of

China. Although they

did not

conceal their ideological affinity with

the

Soviet Union, they were

not

certain

of the

extent

to

which they would

count

on

Russian support against

the

Nationalists.

It

would

be

unrealistic,

then,

to

work

out

their strategy

in the

Chinese civil war

on the

assumption

that Russia would become involved

in

China

as

part

of the

global

confrontation with

the

United States.

As

Okabe Tatsumi

has

shown,

the

Communist leadership devised

a

theory

of an

intermediate zone,

in

between

the two

giant powers, which

was

pictured

as

struggling

for

freedom from American imperialism.

It was

this struggle,

in

Communist

conception, rather than the Cold War, that provided the immediate setting

for

the

Chinese civil

war and

justified

the

strategy

of

an all-out offensive

against

the

forces

of

Chiang Kai-shek.

74

Both Nationalists and Communists were right

in

assuming that the Cold

War was

not of

immediate relevance

to

China

or, for

that matter,

to

Asia

as

a

whole. American-Soviet rivalry

and

antagonism were most evident

in such countries

as

Iran, Greece

and

Turkey

—

areas

in

which

the

United

States was steadily replacing Britain as

the

main power

in

contention with

Russia. After

1947,

moreover,

the

recovery

and

collective defence

of

Western Europe became

the

main objectives

of

American policy, whereas

the Soviet Union responded

to

these initiatives

by

consolidating

its

control over Eastern Europe.

In

such

a

situation Asia remained mostly

in

the

background.

The

picture

was

complicated

by the

postwar waves

of nationalism throughout

the

underdeveloped areas

of

the world, which

manifested themselves most strikingly

in

Asia.

But

Asian nationalism

was

only remotely linked

to

Soviet strategy,

nor

could

it be

neatly fitted into

the Anglo-American strategy

of

containment.

As a

perceptive report

of

the under-secretary's committee

of

the Foreign Office

in

London pointed

out,

We

are

faced.. .with

an

intense nationalism which

is

prickly

in its

internationa\

relationships. Though the idea of pan-Asia, sponsored originally by the Japanese,

creates

the

danger

of

a cleavage between East

and

West, there

is, in

fact, little

73

Cbung-jangjib-pao,

6

Sept. 1947.

74

Okabe's essay

in

Nagai

and

Iriye,

eds.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

544 CHINA S INTERNATIONAL POSITION

or no cohesion between Asiatic countries, and it

is

probably true to say that there

is greater fear, distrust and even dislike between Asiatic neighbours than there

is between Asiatic and Western nations. Nevertheless, Asiatic nationalism is

abnormally sensitive to anything which savours of Western domination or

direction... It is unfortunate that the countries of South East Asia and the Far

East should be passing through this stage of their development at a time when

the Soviet Union is seeking to obtain domination over the whole Eurasian

continent.

75

This situation made it extremely difficult for the United States and Britain

to devise a workable strategy to check the Soviet Union jointly with Asian

countries. Britain, in fact, reduced its commitments in the region by

granting independence to India and Pakistan as early as 1947, signalling

its decline as an Asian power. The United States hesitated to act for fear

that it might be seen

as

an upholder of colonialism. It did little in South-East

Asia other than encourage the European nations to concede more rights

to the indigenous populations. In these circumstances there was little

cohesion in British and American approaches to the Chinese civil war.

The two never coordinated their action as closely there as they did in

Europe or the Middle East; in fact, the United States acted virtually

unilaterally in China, often to the annoyance of British officials.

By 1949, when the Communists established their government in Peking

and their claim to represent the whole of China, America's ' total failure',

as a British official put it, was obvious. It had neither prevented the

Communist take-over nor prepared the ground for accepting the fait

accompli. There was, in fact, no policy. Britain, in contrast, had already

begun reorienting its approach and considering the recognition of the

People's Republic. Officials in London and their representatives in Asia

agreed, at a meeting held in November

1949,

the 'British interests in China

and in Hong Kong demand earliest possible de jure recognition of the

Communist Government in China'. The Foreign Office informed the

United States that 'The Nationalist Government were our former allies

in the war and have been a useful friend in the United Nations. Today

they are no longer representative of anything but their ruling clique and

their control over the remaining metropolitan territories is tenuous.'

Britain had to accept the facts and prepare, through recognition of the

new regime, for the day when China and the Soviet Union would develop

a rift.

76

Here, too, British strategy hinged not so much on Anglo-American

cooperation against the Soviet Union, as in Europe, but on a willingness

to look after its own interests in a possible framework of close ties with

the Chinese. The Cold War as such was not immediately relevant.

75

F

17397/105 5/6109,

in FO

371/76030, Foreign Office Papers.

76

F

16589/1023/10,

in FO

371/75819,

ibid.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CHINA S POSTWAR ECLIPSE 545

After the failure of

the

Marshall mission, the United States government

continued to provide a modicum of support to Chiang Kai-shek. But this

was more in response to domestic pressures within America, where some

erstwhile advocates of the popular front (Max Eastman, Whittaker

Chambers, Freda Utley, et al.) were emerging as Cold Warriors and

accusing others (Alger Hiss, Owen Lattimore,

et al.)

of having been dupes

or, worse, agents of Soviet communism. In order to nullify the criticism

that it was not doing enough to combat communism, the Truman

administration extended economic and military aid, totalling US $3.5

billion, to the Kuomintang regime. But the programme of assistance never

implied a commitment to involve the United States in force on the side

of the Nationalists. Neither the joint chiefs nor the National Security

Council (established in 1947) were willing to spread national resources thin

when it was considered to be of primary importance to concentrate on

the defence of the status quo in Western Europe and parts of the Middle

East.

The Soviet Union also remained extremely cautious about developments

in China. As if to belie the picture of Moscow's collusion with the

Chinese Communists, the USSR continued to deal with the Nationalists

as the government of China, its ambassador travelling with them all the

way to Canton when they were driven out of Nanking. Stalin was reluctant

to support the Communists openly for fear that it might provoke the

United States. He, no more than Truman or Attlee, was willing to extend

the Cold War to China. If anything, the Soviet government sought to

protect its interests in North-east China (Manchuria) by establishing ties

with Kao Kang, chairman of the people's government in the area.

77

What these developments meant was that China, which was to have

played a leading role in Asian and even in world affairs after 1945, entered

a period of eclipse. From 1945 to 1949 it remained outside the major drama

of international politics centring around the Cold War confrontation

between the United States and the Soviet Union. It was allied to neither,

and the two super-powers did not wish to extend their struggle to this

land torn by civil war. The Nationalist leaders, in the meantime, failed

to capitalize on their victory over Japan. They got neither American-Soviet

cooperation, nor an alliance with one of them against the other -

possibilities that would have better ensured their position.

Rather, they were left to their own devices against the increasingly

confident Communists, who took the offensive. Chiang Kai-shek and his

followers in 1949 took the dream of China's big-power status with them

to the island of Taiwan. It would be another twenty years before China,

77

Nakajima's essay in Nagai and Iriye, eds.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

546 CHINA'S INTERNATIONAL POSITION

under a different leadership, would re-emerge on the world arena in the

role of leader of 'the third world'.

Japan, in contrast, was brought back into the international scene much

sooner than its former enemies, or even the Japanese themselves, had

anticipated. The Cold War by definition meant, as noted above, the

discarding of the popular front for reintegrationism, and this was

tantamount to restoring the framework of appeasement of Germany and

Japan. In fact, for postwar US foreign policy, Germany and Japan,

together with Britain and Western Europe, became the cornerstone of

international stability, on the basis of which the Soviet Union and its

associates were to be kept from disrupting the status quo. By 1949,

American-Japanese ties were replacing the United States-Chinese con-

nection as the key to Asian-Pacific affairs.

The story of China's international position from 1931 to 1949 indicates

that Japanese aggression, and the ways in which other nations coped with

it, served steadily to transform the country from being a weak victim of

invasion into a world power, a partner in defining a stable framework

of peace. But the story also reveals that it is more difficult to define a

nation's position in peace than in war. In war, as Clausewitz noted long

ago,

to know who the enemy is defines national politics and policies. In

peace, it is not easy to say who the potential enemies are. Having

bequeathed an enhanced status of the country to their successors, the

Nationalists also left with the Communists the task of defining the

peacetime objectives of the country's foreign policy. In the long

perspective of the twentieth century, which has been convulsed by wars

and revolutions, it remains to be seen if national policies can be defined

and strengthened without war. The Nationalists did not have the

opportunity to answer that question. But it was not altogether their fault.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CHAPTER

11

NATIONALIST CHINA DURING THE

SINO-JAPANESE WAR 1937-1945

It lasted eight

years.

Some fifteen to twenty million Chinese died as a direct

or indirect result.' The devastation of property was incalculable. And after

it

was

over

the

Nationalist government

and

army were exhausted

and

demoralized. Thus

it

inflicted

a

terrible toll

on the

Chinese people

and

contributed directly

to the

Communist victory

in

1949.

The war

with

Japan

was

surely

the

most momentous event

in the

history

of the

Republican

era

in

China.

INITIAL CAMPAIGNS

AND

STRATEGY

I 9

3

7-1 9

3

9

The fighting began

in

darkness, not long before midnight

on

7 July 1937.

Since 1901,

in

accordance with

the

Boxer Protocol,

the

Japanese

had

stationed troops

in

North China between Tientsin

and

Peiping.

And

on

that balmy summer night,

a

company

of

Japanese troops was conducting

field manoeuvres near

the

Lu-kou-ch'iao (Marco Polo Bridge), fifteen

kilometres from Peiping and site

of

a

strategic rail junction that governed

all traffic with South China. Suddenly,

the

Japanese claimed, they were

fired upon

by

Chinese soldiers.

2

A

quick check revealed that one

of

their

1

Precise and reliable figures

do

not exist. Two official estimates:

(i)

Chiang Kai-shek

in

1947 stated

that

the

number

of'

sacrifices'

by

the

military and civilians was

'

ten million'

{cb'ten-wan) —

clearly

a loose approximation.

Kuo-cbia

tsmg-tung-yuan (National general mobilization),

4.

(2) The officially

sancaoacd

Chiang

tsung-t'ungmi-/u (Secret records

of

President Chiang),

15.

199, records 3,311,419

military

and

over 8,420,000 non-combat 'casualties'.

The

number

who

died from war-related

causes

-

starvation, deprivation

of

medicine, increased incidence

of

infectious diseases, military

conscription, conscript labour,

etc.

-

was doubtless very large.

Ho

Ping-ti's estimate

of

1

j-20

million deaths seems credible (Studies on

tie

population

of

China, ij6S-i?;j,

252).

Ch'en Ch'i-t'ien

put

the

total deaths

at

18,$46,000,

but did not

indicate

his

source (Wo-te bui-i

(My

memoirs),

235).

Chiang Kai-shek's

son,

Wego

W.

K.

Chiang, more recently

put the

number

of

casualties'

at

3.2

million

for the

military

and

'some twenty-odd millions'

for

civilians ('Tribute

to our

beloved leader', Part

II,

China Post (Taipei),

29

Oct.

1977,

4).

2

It

has

been stated that

the

initial shooting

may

not

have been

by

soldiers from

the

Wan-p'ing

garrison,

but

from

a

third party, possibly

the

Communists,

who

hoped thereby

to

involve

the

National government

in a war

with Japan.

The

charge

is not,

however, supported

by

firm

evidence.

See

Hata Ikuhiko, Nitchu senso

sbi

(History

of the

Japanese-Chinese

War),

181-3;

Tetsuya Kataoka, Resistance and

revolution

in

China: the Communists and the

second

united front, 54—5;

Alvin

D.

Coox, 'Recourse

to

arms:

the

Sino-Japanese conflict, 1937-1945',

in

Alvin

D.

Coox

and Hilary Conroy, eds. China and Japan:

a

search for

balance since

World

War I,

299.

547

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

548 NATIONALIST CHINA, I937-I945

number was missing, whereupon they demanded entry

to

the nearby

Chinese garrison town of Wan-p'ing to search for him. After the Chinese

refused, they attempted unsuccessfully to storm the town. This was the

initial clash of the war.

That the Japanese must ultimately bear the onus for the war is not in

question; their record

of

aggression against China

at

least since

the

Twenty-one Demands in 1915, and especially since they seized Manchuria

in 1931, was blatant. Yet precisely what happened at Lu-kou-ch'iao and

why

is

still debated. The Chinese have generally contended that

the

Japanese purposely provoked

the

fighting.

The

Japanese goal

was

allegedly

to

detach North China from the authority

of

the Nanking

government;

by

seizing control

of

the Lu-kou-ch'iao-Wan-p'ing area,

they could control access

to

Peiping and thereby force General Sun

Che-yuan, commander of the 29th Army and chairman of the Hopei-Chahar

Political Council, to become a compliant puppet. Moreover, the argument

continues, the Japanese had witnessed the growing unity of the Chinese

and chose

to

establish their domination

of

the Chinese mainland now

before the Nationalists became strong.

Evidence supporting this contention is not lacking. In September 1936,

for example, the Japanese had taken advantage

of

a similar incident

to

occupy Feng-t'ai, which sat astride the railway from Peiping to Tientsin.

Later the same year they had attempted in vain to purchase some 1,000

acres of land near Wan-p'ing for a barracks and airfield. Japanese military

commanders had also become concerned during the spring

of

1937 that

Sung Che-yuan was falling more under the influence

of

Nanking, thus

threatening their position in North China. And, for

a

week prior to the

incident, Peiping had been in a state of tension: rumours announced that

the Japanese would soon strike;

the

continuation

of

Japanese field

exercises for a week at such a sensitive spot as Lu-kou-ch'iao was unusual

and disturbing; pro-Japanese hoodlums were creating disturbances

in

Peiping, Tientsin and Pao-ting. Significantly, too, the Japanese on 9 July

informed the Chinese that the supposedly missing soldier had reappeared,

apparently never having been detained or molested by the Chinese.

3

Japanese documents

of the

period suggest, however, that

the

Japanese neither planned nor desired the incident

at

Lu-kou-ch'iao.

In

1937,

the Tokyo government was pursuing

a

policy emphasizing industrial

development as

a

means of strengthening the foundations of its military

3

Wu Hsiang-hsiang, Ti-erb-t^u

Chung-Jib cban-cbatg sbib

(The second Sino-Japanese War), hereafter

CJCC

1.359-80;

Li Yun-han,

Sung

Cbe-juanju

(b'i-cb'i

k'ang-cban

(Sung Che-yuan and the 7 July

war of resistance), 179-z

12;

Li Yun-han,' The origins of the war: background of the Lukouchiao

incident, July

7,

1937',

in

Paul K. T. Sih, ed. Nationalist China

during

the

Sino-Japanese

War,

>937-'94h 18-27; T. A. Bisson, japan in

China,

1-39.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

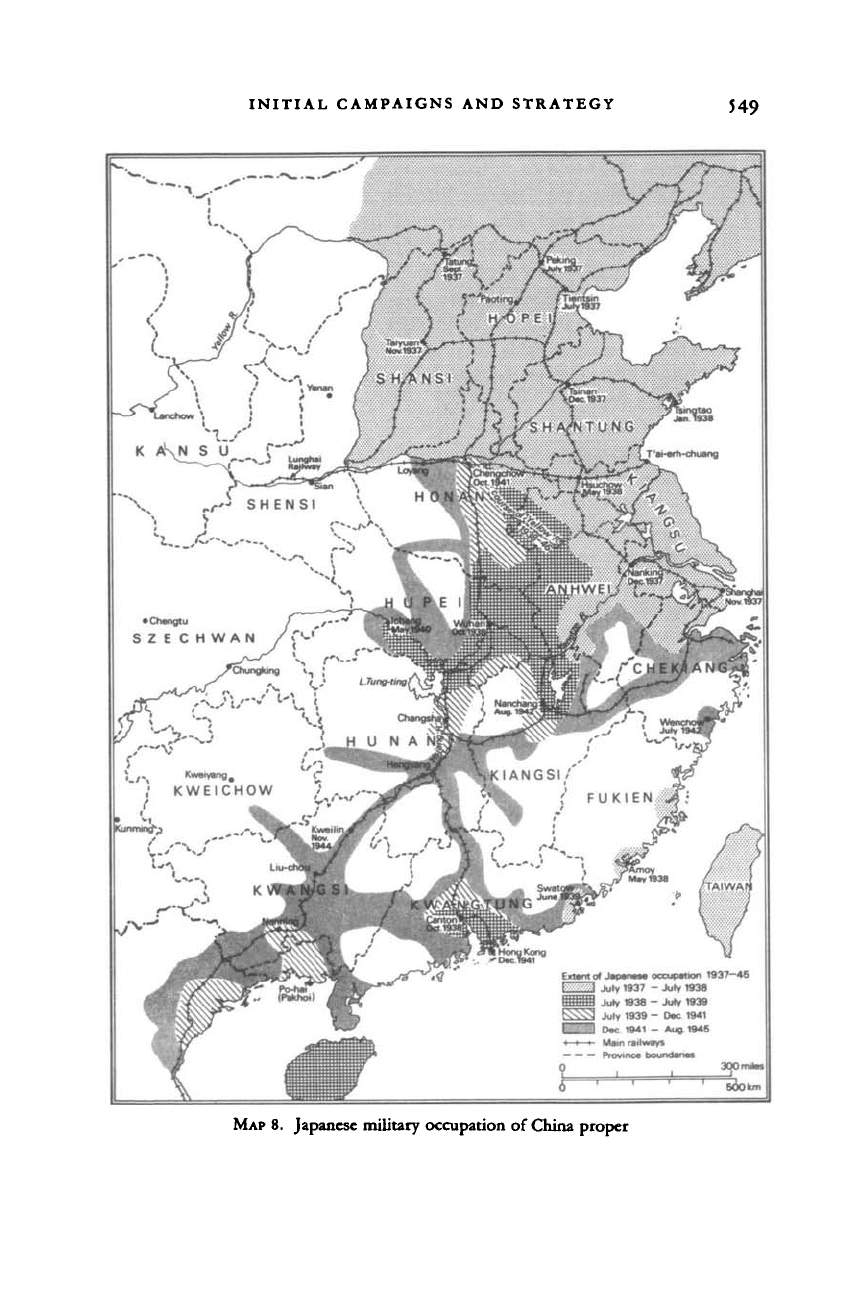

INITIAL CAMPAIGNS AND STRATEGY

549

• Changtu

SZECHWAN

/ p-

Extant

o*

Japanaa* occupation 1937-45

l>>--^vv:1 Juty 1937

-

Juty 1938

IIHIUIII July 1938

-

Juty

1939

KSNS1 July 1939

- Dae

1941

n

Dec

1941

-

Aug.

1945

*

* *

Main

railways

Province boundariaa

i3oton

MAP

8.

Japanese military occupation

of

China proper

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

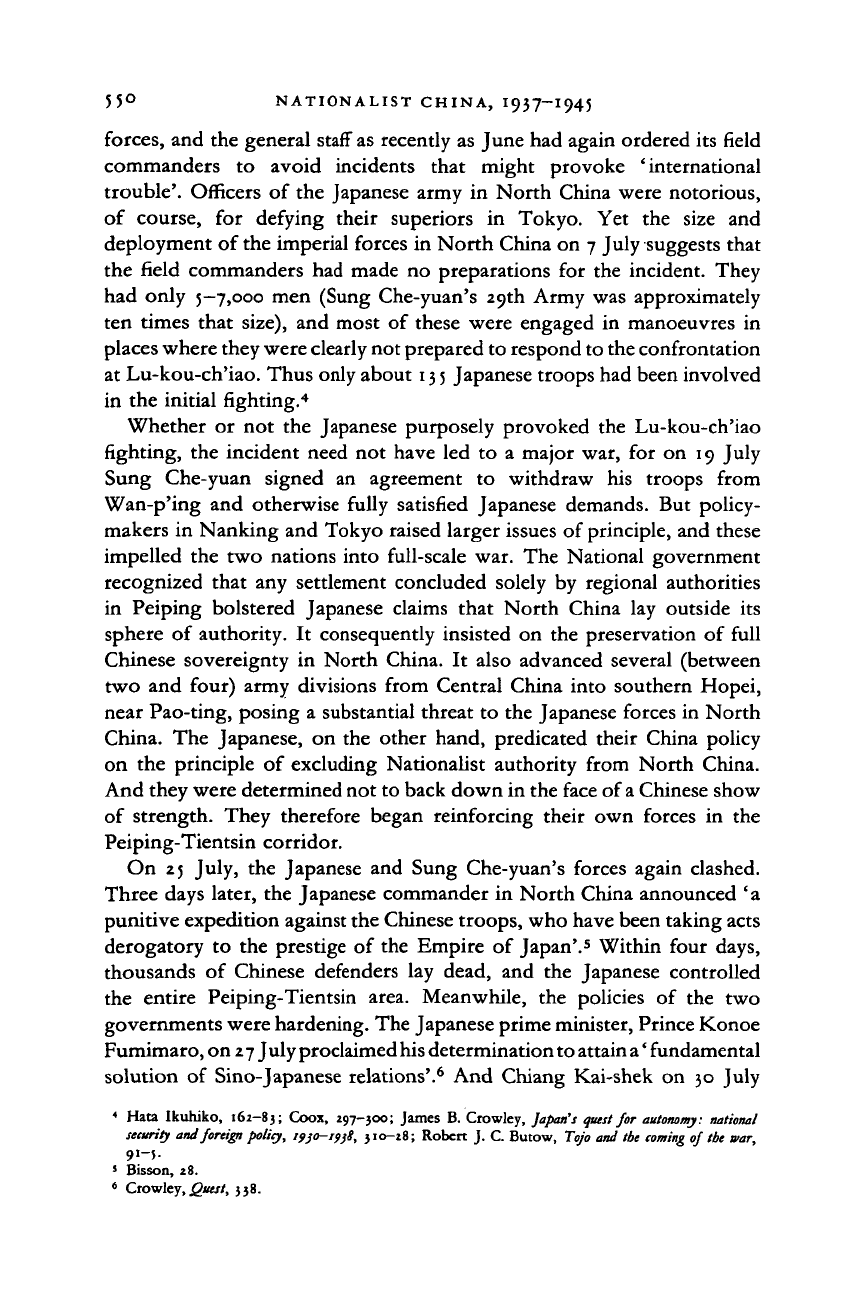

55° NATIONALIST CHINA,

forces, and the general staff

as

recently as June had again ordered its field

commanders to avoid incidents that might provoke 'international

trouble'. Officers of the Japanese army in North China were notorious,

of course, for defying their superiors in Tokyo. Yet the size and

deployment of the imperial forces in North China on 7 July suggests that

the field commanders had made no preparations for the incident. They

had only 5-7,000 men (Sung Che-yuan's 29th Army was approximately

ten times that size), and most of these were engaged in manoeuvres in

places where they were clearly not prepared to respond to the confrontation

at Lu-kou-ch'iao. Thus only about

13 5

Japanese troops had been involved

in the initial fighting.

4

Whether or not the Japanese purposely provoked the Lu-kou-ch'iao

fighting, the incident need not have led to a major war, for on 19 July

Sung Che-yuan signed an agreement to withdraw his troops from

Wan-p'ing and otherwise fully satisfied Japanese demands. But policy-

makers in Nanking and Tokyo raised larger issues of principle, and these

impelled the two nations into full-scale war. The National government

recognized that any settlement concluded solely by regional authorities

in Peiping bolstered Japanese claims that North China lay outside its

sphere of authority. It consequently insisted on the preservation of full

Chinese sovereignty in North China. It also advanced several (between

two and four) army divisions from Central China into southern Hopei,

near Pao-ting, posing a substantial threat to the Japanese forces in North

China. The Japanese, on the other hand, predicated their China policy

on the principle of excluding Nationalist authority from North China.

And they were determined not to back down in the face of

a

Chinese show

of strength. They therefore began reinforcing their own forces in the

Peiping-Tientsin corridor.

On 25 July, the Japanese and Sung Che-yuan's forces again clashed.

Three days later, the Japanese commander in North China announced

' a

punitive expedition against the Chinese troops, who have been taking acts

derogatory to the prestige of the Empire of Japan'.

5

Within four days,

thousands of Chinese defenders lay dead, and the Japanese controlled

the entire Peiping-Tientsin area. Meanwhile, the policies of the two

governments were hardening. The Japanese prime minister, Prince Konoe

Fumimaro, on 2

7

J uly proclaimed

his

determination to attain a' fundamental

solution of Sino-Japanese relations'.

6

And Chiang Kai-shek on 30 July

4

Hata Ikuhiko, 162-83; Coox, 297-300; James B. Crowley, Japan's quest for autonomy: national

security and foreign policy, ifjo-if)t, 310-28; Robert J. C Butow, Tofo and the coming of the war,

91-5.

s

Bisson, 28.

6

Ctoviley,

Quest,

338.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008