The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 13: Republican China 1912-1949, Part 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

THE EARLY WAR YEARS 1937-I938 64I

22 January 1938, Chiang Kai-shek and Yen Hsi-shan reluctantly approved

the establishment of the Chin-Ch'a-Chi Border Region. Of all the bases

established by the CCP behind Japanese lines, it was the only one to

achieve formal central government recognition. Simultaneous with the

development of

CCC,

Ho Lung's 120th Division was active in north-west

Shansi - an area almost as poor and backward as SKN - in what was

to become the Shansi-Suiyuan (Chin-Sui) base. Chin-Sui was important

primarily as a strategic corridor linking the Yenan area with bases farther

east, and as a shield partially protecting the north-east quadrant of SKN.

Liu Po-ch'eng moved his 129th Division into the T'ai-hang mountains

of south-east Shansi, near its boundaries with Hopei and Honan. This

region, together with a part of western Shantung, became the Chin-

Chi-Lu-Yii base (CCLY). For most of the war, this was really two loosely

integrated bases, one west of the Ping-Han railway line, the other to the

east. Later to develop was the peninsular Shantung base, further from

the main strength of the 8RA, where struggles between Communists,

Japanese, puppets, local forces, and units affiliated with the central

governments were very complex.

In Central China, certain differences from North China slowed the

development of CCP influence. In the areas attacked most forcefully by

Japan, especially the Yangtze delta and the Shanghai-Nanking axis, local

administration often broke down, order disintegrated, and armed bands

of all types quickly appeared, just as in the north. Here too, the Japanese

paid scant attention at first to occupying the regions through which they

passed. But elsewhere, Central China was somewhat less disrupted by the

Japanese invasion. Local and provincial administrations continued to

function, often in contact with Nationalist-controlled Free China. In those

parts of Anhwei and Kiangsu north of the Yangtze River which had not

been directly subject to Japanese attack, Nationalist armies remained,

without retreating. South of the Yangtze in the Chiang-nan area, though

most Nationalist forces retreated at

first,

some units were soon reintroduced

and more followed. Many of these forces were either elements of the

Central Armies or closely associated with Chiang Kai-shek, unlike the

regional 'inferior brands' of military

{tsa-p'ai chiiri)

in trie 8RA's

areas.

This

region had been, after all, the core area of KMT power, the Nationalists

were very sensitive about intrusions, and they were in a better position

to thwart such efforts.

Although the New Fourth Army was smaller and for several years less

effective than the Eighth Route Army, Mao Tse-tung and Liu Shao-ch'i

were soon to call for aggressive base-building throughout this area,

especially north of the Yangtze. Officially, the Nationalists assigned to

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

642 THE CHINESE COMMUNIST MOVEMENT, I937-I945

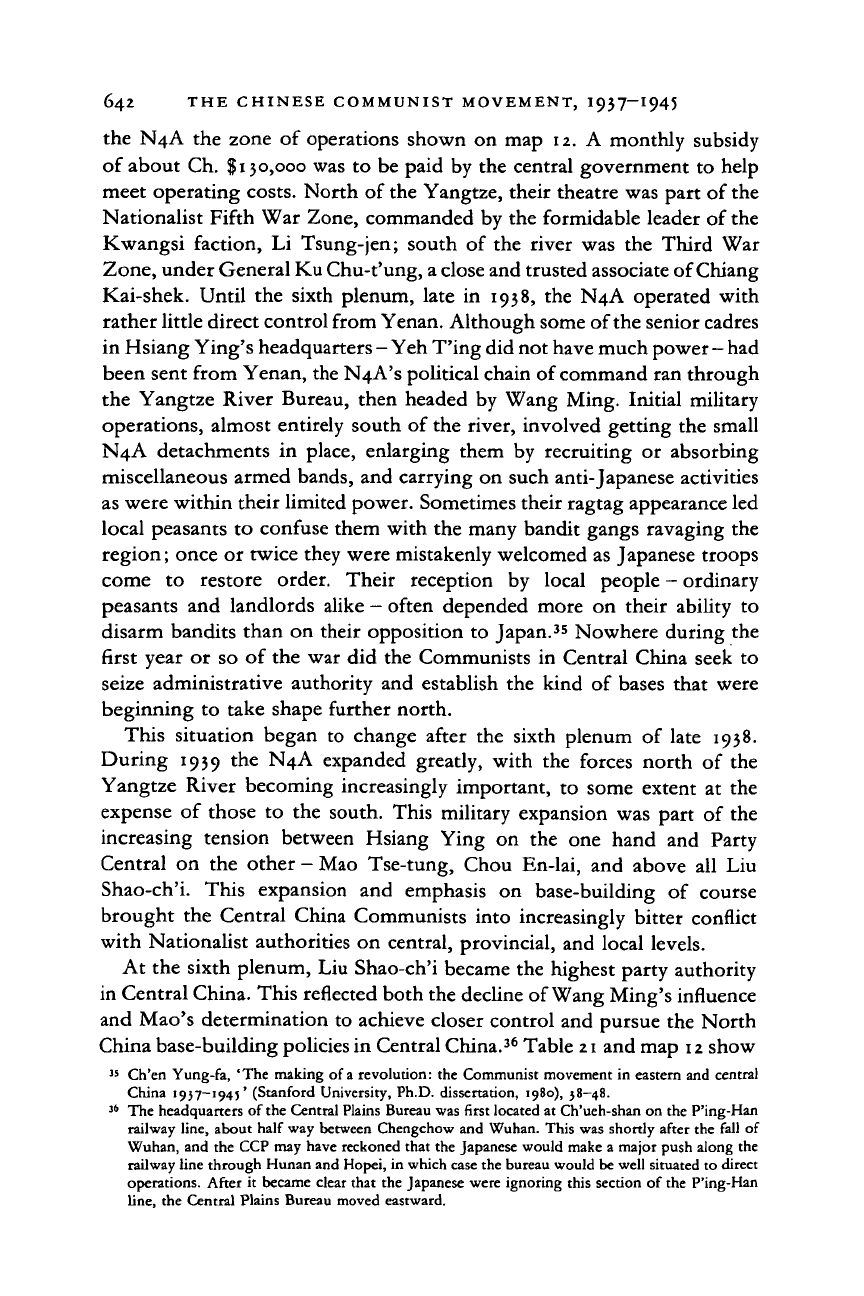

the N4A the zone

of

operations shown on map 12.

A

monthly subsidy

of about Ch. $130,000 was to be paid by the central government to help

meet operating costs. North of the Yangtze, their theatre was part of the

Nationalist Fifth War Zone, commanded by the formidable leader of the

Kwangsi faction,

Li

Tsung-jen; south

of

the river was the Third War

Zone, under General Ku Chu-t'ung, a close and trusted associate of Chiang

Kai-shek. Until the sixth plenum, late

in

1938, the N4A operated with

rather little direct control from Yenan. Although some of the senior cadres

in Hsiang Ying's headquarters

-

Yeh T'ing did not have much power - had

been sent from Yenan, the N4A's political chain of command ran through

the Yangtze River Bureau, then headed by Wang Ming. Initial military

operations, almost entirely south of the river, involved getting the small

N4A detachments

in

place, enlarging them

by

recruiting

or

absorbing

miscellaneous armed bands, and carrying on such anti-Japanese activities

as were within their limited power. Sometimes their ragtag appearance led

local peasants to confuse them with the many bandit gangs ravaging the

region; once or twice they were mistakenly welcomed as Japanese troops

come

to

restore order. Their reception

by

local people

-

ordinary

peasants and landlords alike

—

often depended more

on

their ability

to

disarm bandits than on their opposition to Japan.

35

Nowhere during the

first year

or

so

of

the war did the Communists in Central China seek

to

seize administrative authority and establish the kind

of

bases that were

beginning to take shape further north.

This situation began

to

change after the sixth plenum

of

late 1938.

During 1939 the N4A expanded greatly, with the forces north

of

the

Yangtze River becoming increasingly important,

to

some extent

at

the

expense

of

those

to

the south. This military expansion was part

of

the

increasing tension between Hsiang Ying

on the

one hand

and

Party

Central

on

the other

-

Mao Tse-tung, Chou En-lai, and above

all

Liu

Shao-ch'i. This expansion

and

emphasis

on

base-building

of

course

brought the Central China Communists into increasingly bitter conflict

with Nationalist authorities on central, provincial, and local levels.

At the sixth plenum, Liu Shao-ch'i became the highest party authority

in Central China. This reflected both the decline of Wang Ming's influence

and Mao's determination to achieve closer control and pursue the North

China base-building policies in Central China.

36

Table

21

and map 12 show

" Ch'en Yung-fa, ' The making of

a

revolution: the Communist movement in eastern and central

China 1937—1945' (Stanford University, Ph.D. dissertation, 1980), 38-48.

36

The headquarters of the Central Plains Bureau was first located at Ch'ueh-shan on the P'ing-Han

railway line, about half way between Chengchow and Wuhan. This was shortly after the fall of

Wuhan, and the CCP may have reckoned that the Japanese would make a major push along the

railway line through Hunan and Hopei, in which case the bureau would be well situated to direct

operations. After

it

became clear that the Japanese were ignoring this section of the P'ing-Han

line,

the Central Plains Bureau moved eastward.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE EARLY WAR YEARS I937—1938 643

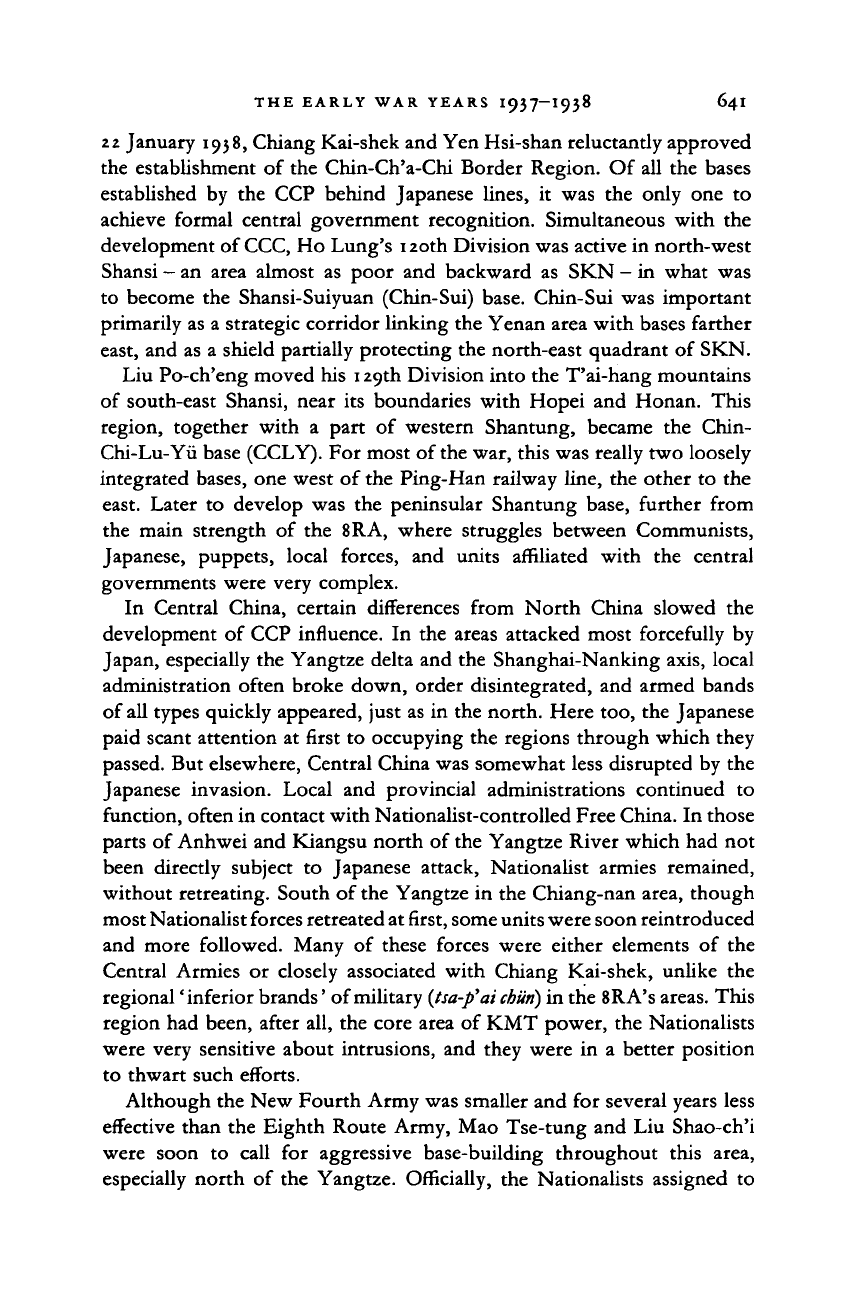

TABLE 21

New

Fourth

Army

{late

ipjp)

Headquarters

CO: Yeh Ting. Vice CO/Political Officer: Hsiang Ying. Chief of

Staff:

Chang Yun-i.

Head, Political Dept.: Yuan Kuo-p'ing. Vice-head: Teng Tzu-hui.

South Yangtze

Command

(formed July 1939)

1st Detachment. CO: Ch'en I. Efforts to expand east and south of Lake T'ai during 1939 were

not very successful. Most of these forces were transferred north of the Yangtze River,

March—June 1940.

2nd Detachment. CO: Chang Ting-ch'eng. In early 1939, Lo Ping-hui led part of these forces

across the Yangtze to help form the 5 th Detachment, placed under his command.

3rd Detachment. CO: T'an Chen-lin.

North

Yangtze Command

(formed July 1939). CO: Chang Yun-i.

4th Detachment. CO: Tai Chi-ying. Originally formed from Communist remnants surviving

north of Wuhan in the Ta-pieh mountains of Hupei (near Huang-an), the old O-Yii-Wan

soviet. Led by Kao Ching-t'ing, a former poor peasant butcher. Kao resisted N4A orders,

discipline; refused collaboration with KMT forces. He reluctantly moved east to Lake Chao

(Anhwei), was denounced as a 'tyrannical warlord', and was executed in April 1939 by order

of Yeh Ting after a public trial. Some elements of the 4th Det. were sent to help form the

j

th Det. The 4th Det. served mainly as a training unit.

jth Detachment. CO: Lo Ping-hui. Formed in spring 1939 at Lu-chiang, SW of Lake Chao;

moved to Lai-an/Iiu-ho area on the Kiangsu-Anhwei border, opposite Nanking, in July

1939.

In late 1939, moved further east to the Lake Kao-yu/Grand Canal area in Kiangsu. ;th

Det. saw much combat with both Nationalists and Japanese.

6th Detachment. CO: P'eng Hsueh-feng. Formed in the summer of 1939 from elements sent

south into Honih from the 8RA. Absorbed many local armed groups and stragglers from

Nationalist armies. In early 1940, moved from eastern Honan (Tai-k'ang/Huai-yang)

eastward into northern Anhwei. 6th Det. was the main military and base-building force in

northern Anhwei and northern Kiangsu.

Note: in recent years Kao Ching-t'ing has been posthumously rehabilitated; it is said he was traduced

and wrongly executed in 1939.

Sources:

from material in Ch'en Yung-fa, ch. 2, and Johnson,

Peasant

nationalism,

124—32.

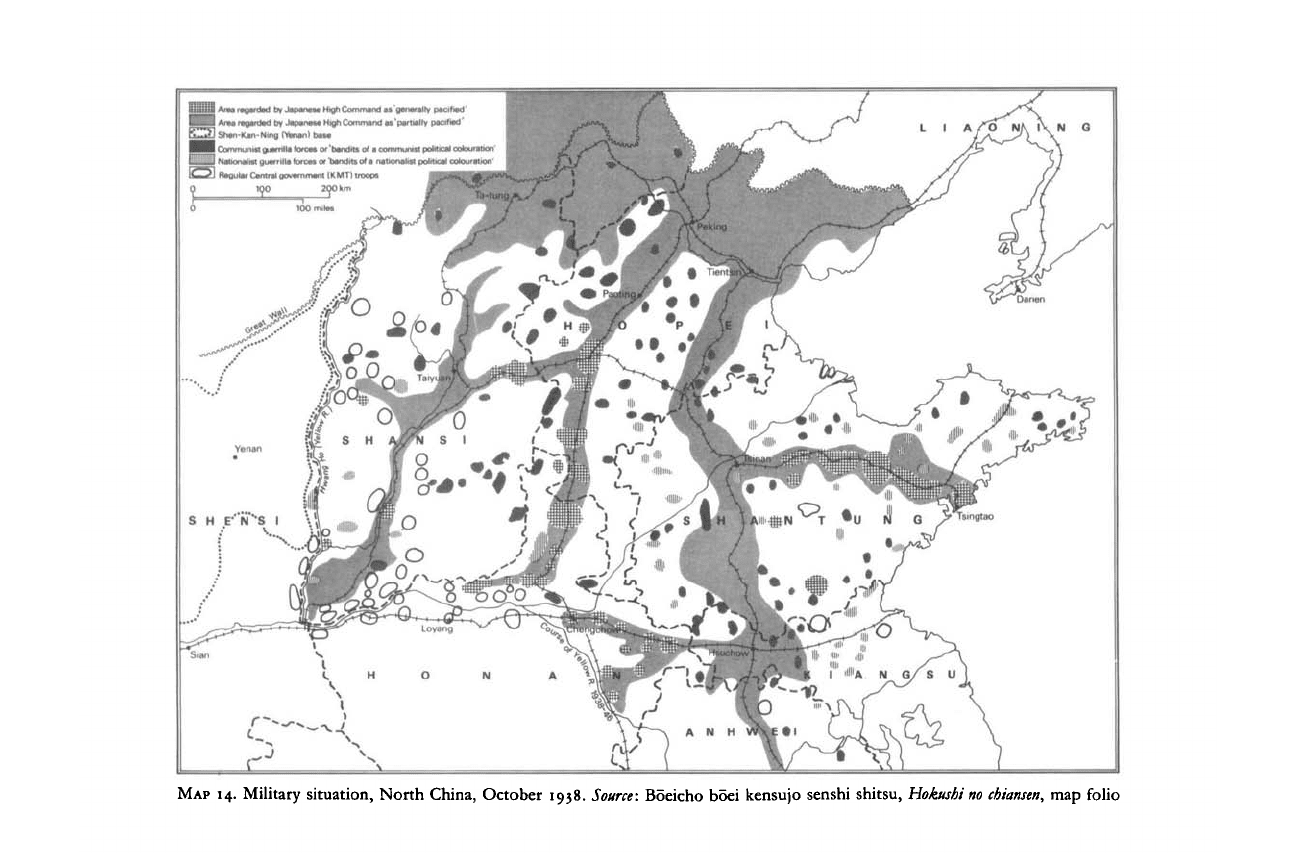

the N4A's deployments during the first two years of the war - a general

movement toward the east and north, further behind Japanese lines and

away from the Nationalist rear areas. The most important of the other

military forces affiliated with the N4A was the Honan-Hupei assault

column led by Long March veteran Li Hsien-nien, which took up

positions near those originally occupied by the 4th Detachment, north

of Wuhan astride the P'ing-Han railway line. Li Hsien-nien's column was

not made a formal part of the N4A until 1941, in the reorganization that

followed the New Fourth Army incident. Much further east, and south

of the Yangtze River, were two local semi-guerrilla groups, the Chiang-nan

Anti-Japanese Patriotic Army and the Chiang-nan Assault Column led

by Kuan Wen-wei. Kuan, a local CCP leader (from Tan-yang) who until

1937 had lost touch with the party, helped open up a corridor through

which N4A elements could pass north of the river, across Yang-chung

Island. Both these units and the 1st Detachment contested with the

Chungking-affiliated Loyal National Salvation Army.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

100 miles

200km

K UA N G S U

Huaiyin

• Yench^ing

^Paoying

Tientsin-Pukowl LHungtse

Railway

A N HJWE I

'ungming I

Shanghai

•

Kuangte

(T

Shabhsing

I A N

MAP

12. Disposition and movements of the New Fourth Army, to late 1940.

Source:

Johnson,

Peasant nationalism

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

1

'•-•••••

•'•- U =, H U N

KWEICHOW

; Kweiyang

6 km 300

IRTH CHINA

t Shensi-Kansu-Ninghsia (Shen-Kan-Ning)

Z Shansi-Suiyuan (Cnin-Sui)

3. Shansi-Chahar-Hopei (Chin-Ch'a-Chi)

SSISSSSX}

SISSS

6. Shantung

CENTRAL CHINA

7.

NorthAnhwei (HuaHpei) 11. South

Kiangsu

(Su-nan)

8NorthKiangsu(Su-pei)

12.

Central

Anhwei Mfen-ohung)

9.Central

Kiangsu(Su-chung)

n

East Chekiang(Che-tung)

ntSouthAnnweilHuai-nanr 14. Hupeh-Hunan-Anhwei

SOUTH CHINA (C^Vu-Wan)

ISLKwangtung (Tung-chiang) 16. Hainan (Ch'iung-yai)

MAP

13.

Communist bases

as

claimed overall (late. 1944).

Source:

Van

Slyke,

Chinese

Communist

movement,

xii-xiii. This map has been prepared from CCP sources dated August

and October 1944.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

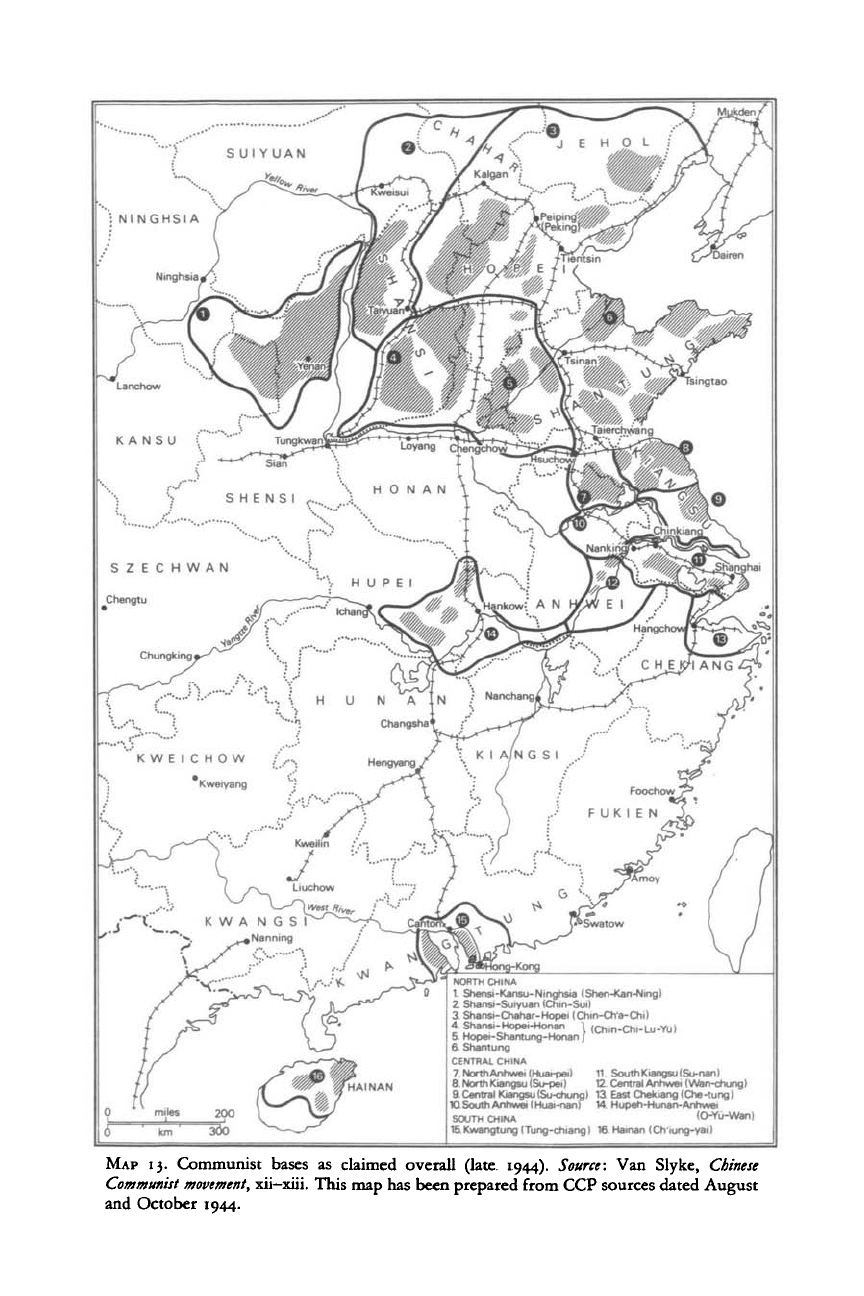

646 THE CHINESE COMMUNIST MOVEMENT, 1937-1945

Map

13

shows

the

approximate location

of

the Communist bases,

but

like most simplified

CCP

maps prepared late

in the war for

public

consumption, this

map

shows large, contiguous areas under Communist

control. This is quite misleading. The bases were in widely different stages

of development

and

consolidation, from

SKN and

CCC

in

the

north

to

the

two

shadowy

and

insubstantial guerrilla zones

not far

from Canton.

A more realistic

but

still simplified picture would show three kinds

of

territories,

all

quite fluid,

(i)

Zones

in

which

the

CCP had created

a

fairly

stable administration, able

to

function openly

and

institute reforms that

were quite frankly less than revolutionary

but

nevertheless more

far-

reaching and deeply rooted

in

local society than any Chinese government

had previously achieved. These core areas were islands within

the

larger

expanse

of

bases shown

on

unclassified CCP maps.

(2)

More ambivalent

regions, often referred

to in

Communist sources

as

' guerrilla areas'

and

in Japanese sources

as

'neutral zones'. These might contain several types

of forces: Communists,

KMT

elements, local militia, bandits, puppet

forces.

In

these guerrilla areas,

the

CCP

sought allies

on the

basis

of

immediate sharing

of

common interests. They

did

only preliminary

organizational work, and attempted only modest reform. (3) Areas subject

in varying degrees

to

Japanese control. Cities, larger towns,

and

main

communications corridors were

the

Japanese counterparts

of

the CCP's

core areas, alongside which lay

a

fluctuating penumbra

of

territory where

the Japanese

and

puppet forces held

the

upper hand.

In North China, especially,

the

railway lines both defined

and

divided

the major base areas. Chin-Ch'a-Chi lay

to

the east

of

the Tatung-Taiyuan

line,

and north of the Cheng-Tai. The core areas of

the

base were separated

from each other by the P'ing-Han, the P'ing-Sui, and the Peiping-Mukden

lines.

With variations, this pattern

was

repeated

in

the

other base areas.

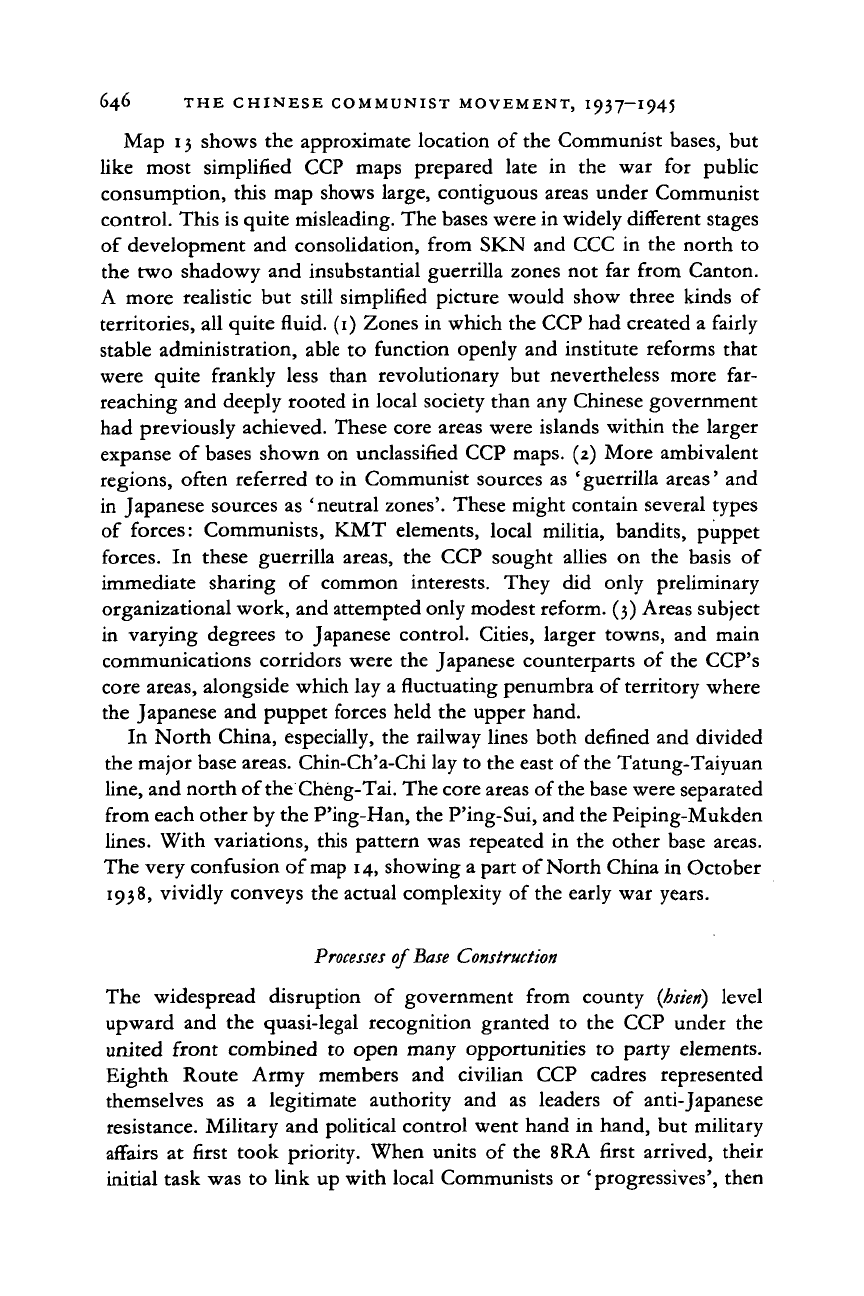

The very confusion

of

map

14, showing a part of North China

in

October

1938,

vividly conveys the actual complexity

of

the early

war

years.

Processes

of

Base Construction

The widespread disruption

of

government from county

(bsieri)

level

upward

and the

quasi-legal recognition granted

to

the CCP

under

the

united front combined

to

open many opportunities

to

party elements.

Eighth Route Army members

and

civilian

CCP

cadres represented

themselves

as a

legitimate authority

and as

leaders

of

anti-Japanese

resistance. Military

and

political control went hand

in

hand,

but

military

affairs

at

first took priority. When units

of

the 8RA

first arrived, their

initial task was

to

link up with local Communists

or

' progressives', then

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

3

AIM

regarded by Japanese High Command as'goneralry pacified'

I

ATM

regarded by Japanese High Command w'partially pacified'

D Shan-Kan-Ning Manan) basa

I Communitt guerrilla forces or 'bandits of a communist political colouration'

u Nationalist guarrilla forces or oonditsof a nationfiltst political colourvtion'

U Regular Central govammant (KMT) troops

iqo 200km

100 mites

MAP

14. Military situation, North China, October

1938.

Source:

Boeicho boei kensujo senshi shitsu,

Hokusbi no

cbiansen,

map folio

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

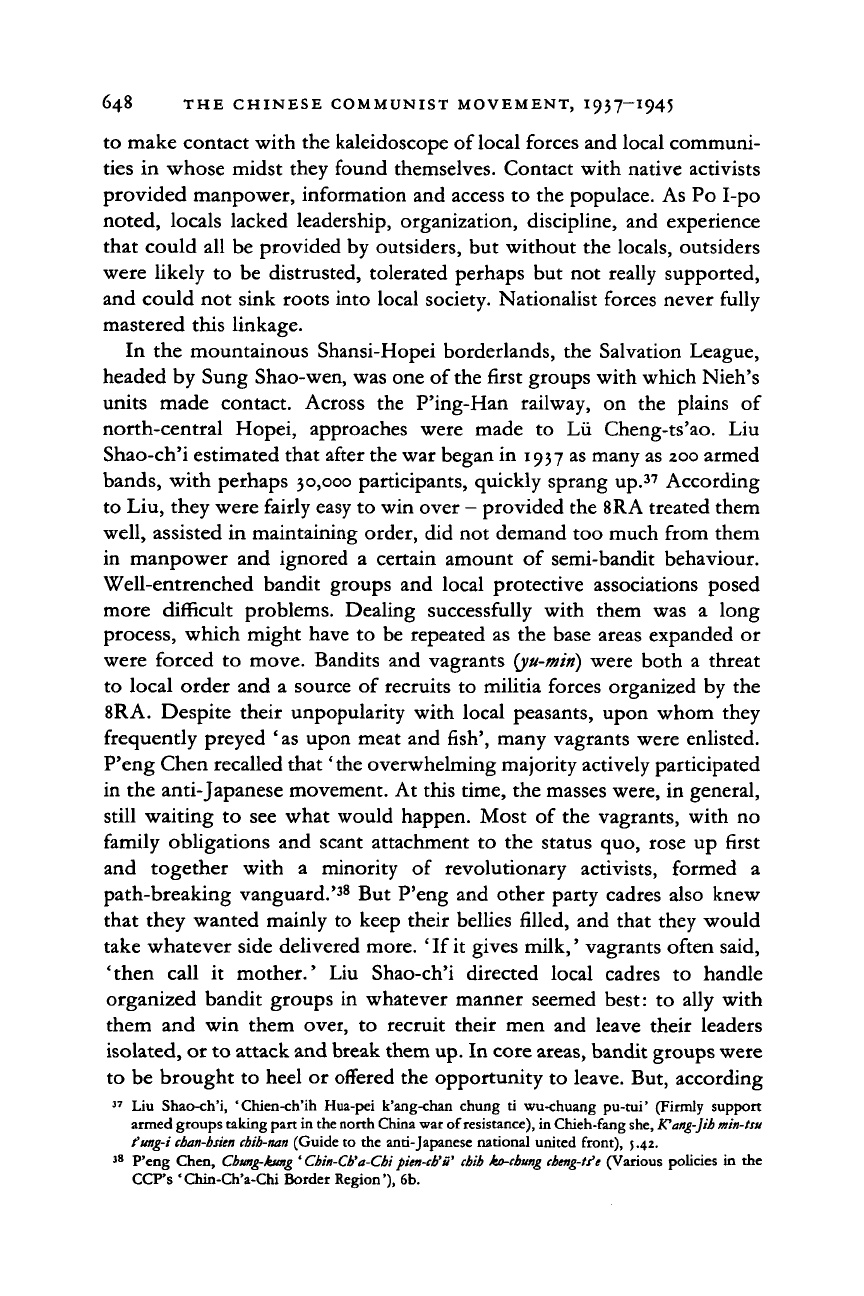

648 THE CHINESE COMMUNIST MOVEMENT, 1937-1945

to make contact with the kaleidoscope of local forces and local communi-

ties

in

whose midst they found themselves. Contact with native activists

provided manpower, information and access to the populace. As Po I-po

noted, locals lacked leadership, organization, discipline, and experience

that could all be provided by outsiders, but without the locals, outsiders

were likely

to

be distrusted, tolerated perhaps but not really supported,

and could not sink roots into local society. Nationalist forces never fully

mastered this linkage.

In the mountainous Shansi-Hopei borderlands, the Salvation League,

headed by Sung Shao-wen, was one of the first groups with which Nieh's

units made contact. Across

the

P'ing-Han railway,

on the

plains

of

north-central Hopei, approaches were made

to Lii

Cheng-ts'ao.

Liu

Shao-ch'i estimated that after the war began in 1937 as many as 200 armed

bands,

with perhaps 30,000 participants, quickly sprang up.

37

According

to Liu, they were fairly easy to win over

-

provided the 8RA treated them

well, assisted in maintaining order, did not demand too much from them

in manpower and ignored

a

certain amount

of

semi-bandit behaviour.

Well-entrenched bandit groups and local protective associations posed

more difficult problems. Dealing successfully with them was

a

long

process, which might have

to

be repeated as the base areas expanded

or

were forced

to

move. Bandits and vagrants (ju-min) were both

a

threat

to local order and

a

source of recruits to militia forces organized by the

8RA. Despite their unpopularity with local peasants, upon whom they

frequently preyed '

as

upon meat and fish', many vagrants were enlisted.

P'eng Chen recalled that 'the overwhelming majority actively participated

in the anti-Japanese movement. At this time, the masses were, in general,

still waiting

to

see what would happen. Most

of

the vagrants, with

no

family obligations and scant attachment

to

the status quo, rose up first

and together with

a

minority

of

revolutionary activists, formed

a

path-breaking vanguard.'

38

But P'eng and other party cadres also knew

that they wanted mainly to keep their bellies filled, and that they would

take whatever side delivered more. ' If it gives milk,' vagrants often said,

' then call

it

mother.'

Liu

Shao-ch'i directed local cadres

to

handle

organized bandit groups

in

whatever manner seemed best:

to

ally with

them and win them over,

to

recruit their men and leave their leaders

isolated, or to attack and break them up. In core areas, bandit groups were

to be brought to heel or offered the opportunity to leave. But, according

37

Liu

Shao-ch'i, 'Chien-ch'ih Hua-pei k'ang-chan chung

ti

wu-chuang pu-tui' (Firmly support

armed groups taking part

in

the north China war of resistance), in Chieh-fang she, ICang-Jib min-tsu

fung-i cban-bsien cbib-nan (Guide

to the

anti-Japanese national united front), j.42.

38

P'eng

Chen,

Cbimg-kimg

'

Cbin-Cb'a-Cbi

pien-cb'S'

cbib ko-cbimg cbtng-tt'e (Various

policies

in the

CCP's 'Chin-Ch'a-Chi Border Region'), 6b.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE EARLY WAR YEARS I937-I938 649

to Liu, 'if local bandits active in the enemy-occupied area are strong

enough to wreck the enemy's order, and if the anti-Japanese forces are

relatively weak there, then we should persuade and unite with the

bandits'.

39

This kind of united front with lumpen elements added

manpower and weapons, and gradually reduced disorder in the base areas.

Local associations were a more difficult problem than bandits, according

to Liu Shao-ch'i, who noted their long history in China and the impetus

added by wartime conditions. The Red Spears, the Heaven's Gate Society,

and joint village associations

(lien-chuang-hui)

were all 'pure self-defence

organizations sharing the goals of resisting exorbitant taxes and levies and

harassment by army units or bandits'. Generally controlled by local elites

and 'politically neutral', they could summon mass support because they

appealed to the 'backward and narrow self-interests' of the peasantry

while the secret societies added superstitious beliefs to other forms of

influence. They were ready to fight all intruders, including anti-Japanese

guerrilla forces. Moreover, if a small force settled in their vicinity, they

often attacked it for its weapons, even if it posed no threat. The

associations had no permanent military organization but could respond

to a summons with 'a very large military force', so long as the action took

place in their local area.

Liu Shao-ch'i summarized the approaches that had proved most

effective, (i) Take no rash action. (2) Strictly observe discipline; make

no demands and do not provoke them, but be very watchful. (3)

Scrupulously avoid insulting their religious beliefs or their leaders; show

respect. (4) When they are harassed by the Japanese or by puppets, help

in driving them away. (5) Win their confidence and respect by exemplary

behaviour and assist them in various ways. (6) Most important, carry on

patient education, propaganda and persuasion in order to raise their

national consciousness, to lead them into the anti-Japanese struggle, and

to provide supplies voluntarily to guerrilla forces. (7) Seek to break up

associations that serve the Japanese. (8) Do not help the associations to

grow, especially in the base areas or in guerrilla zones. (9) In enemy-

occupied territories, help push the associations' self-defence struggles in

the direction of the anti-Japanese movement. Finally, Liu noted that

sometimes superstition could be turned to advantage. Some secret

societies believed that Chu Te, commander of the Eighth Route Army,

must be descended from their patron deity and founder of the Ming

dynasty, Chu Yuan-chang. Relations between these secret societies and

local 8RA units were particularly good. In short, said Liu, 'in many

regions of North China, the anti-Japanese united front in rural villages

35

Liu Shao-ch'i,

'

Chien-ch'ih', 45-6.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

65O THE CHINESE COMMUNIST MOVEMENT,

depends mainly

on

how our relations and work with the associations

is

handled'.

40

Thus the intrusion of Communist influence behind Japanese lines did

not

in the

first instance depend upon nationalism, socio-economic

programmes

or

ideology.

In

fact,

it

was quite feasible

for

possessors

of

military power

to

live

off the

Chinese countryside with

a

different

ideology,

or

with no ideology

at

all, as the following description

of

Sun

Tien-ying makes clear:

One

of

his [Sun's] lieutenants said

to

me, '

The

reason we have an army is so

that everyone gets to eat,' the implication being that whether or not they fought

was unimportant. From the beginning

of

the war

to

the end

of

the war,

he

manoeuvred between the Communists and the central government, even going

over to the Japanese for a time... When the war broke out, he rounded up his

former associates

to

fight Japan. The central government designated his force

the New Fifth Army, with headquarters

in

Lin-hsien, Honan

...

Because

of

connections with the secret societies

(J>ang-hni),

he had contacts everywhere, so

of course

it

was easy to do business and manage things. Although Lin-hsien

is

a small, out-of-the-way place, even goods from Shanghai could be bought and

enjoyed.

41

Everywhere, the CCP viewed military and political control as the essential

prior condition for all other work. The distinction between consolidated,

semi-consolidated and guerrilla zones measured the different degrees

of

such control. At an early stage, the situation might be described as 'open',

in the sense that individuals and groups in society had a variety of options

which the CCP was unable

to

prevent them from exercising.

In

these

circumstances, the united front recognized the party's relative weakness,

and

it

relied mainly

on

persuasion, accommodation, infiltration

and

education.

At the other extreme was

a

'closed' situation,

in

which the CCP was

powerful enough

to

define the options and

to

shape both the incentives

and the costs of choice in such a way as to produce the desired behaviour.

If necessary

the

party could impose coercive sanctions, even violence,

upon those who opposed it. As this control was achieved and deepened,

a kind of political revolution took place, even without any change as yet

in social

and

economic structure.

The

party

and its

followers were

wresting power from the traditional rural power holders, but establishment

of control was

a

gradual and uneven process, influenced

by

terrain,

by

local society, and

by

the presence

of

competing

or

hostile forces. Even

in

the

most successful

of

the base areas, Chin-Ch'a-Chi, progress was

difficult. The masses did not spontaneously rally to the Communist side.

«

Ibid.

48.

41

Ch'ii Chih-sheng,

ICang-cban

tbi-li (A personal account of the war of resistance), 37.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008