The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 13: Republican China 1912-1949, Part 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

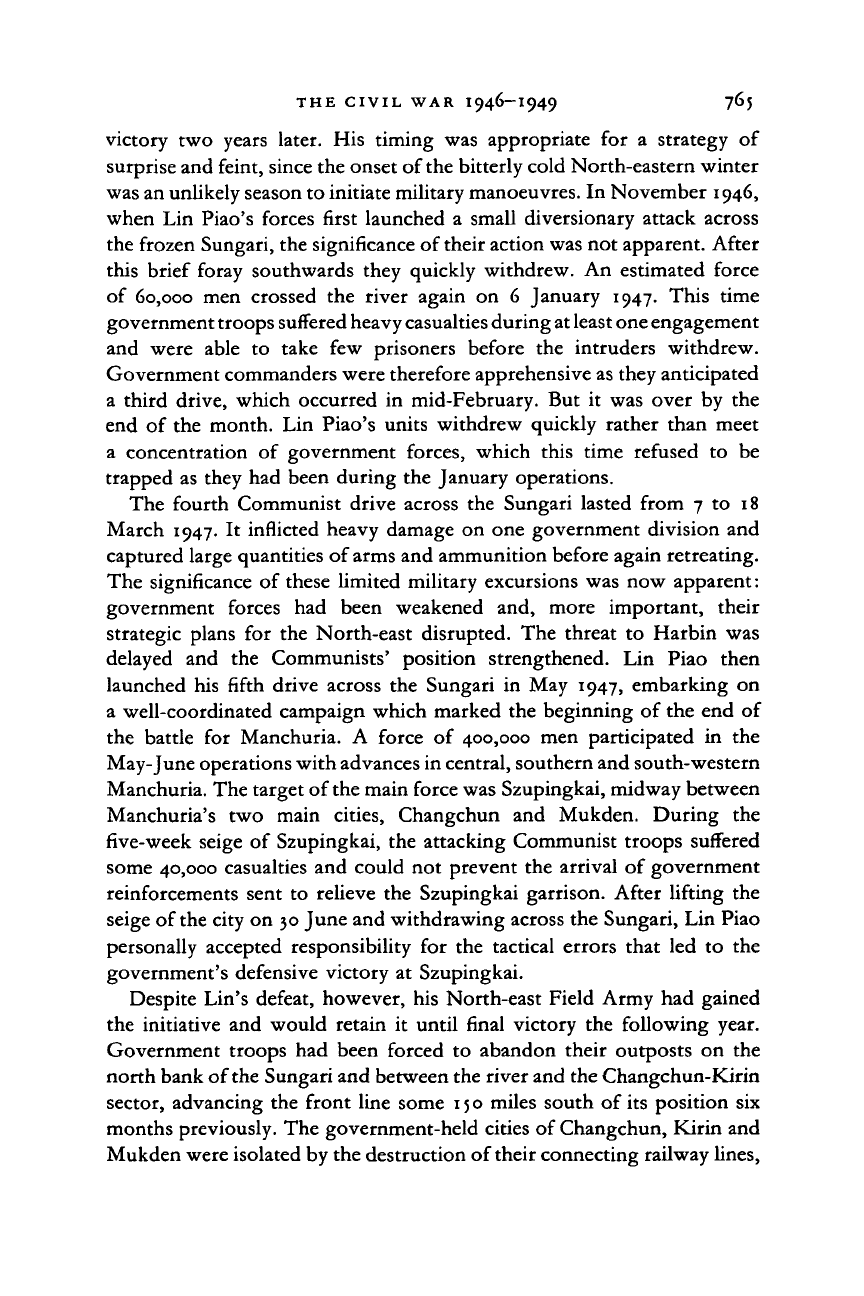

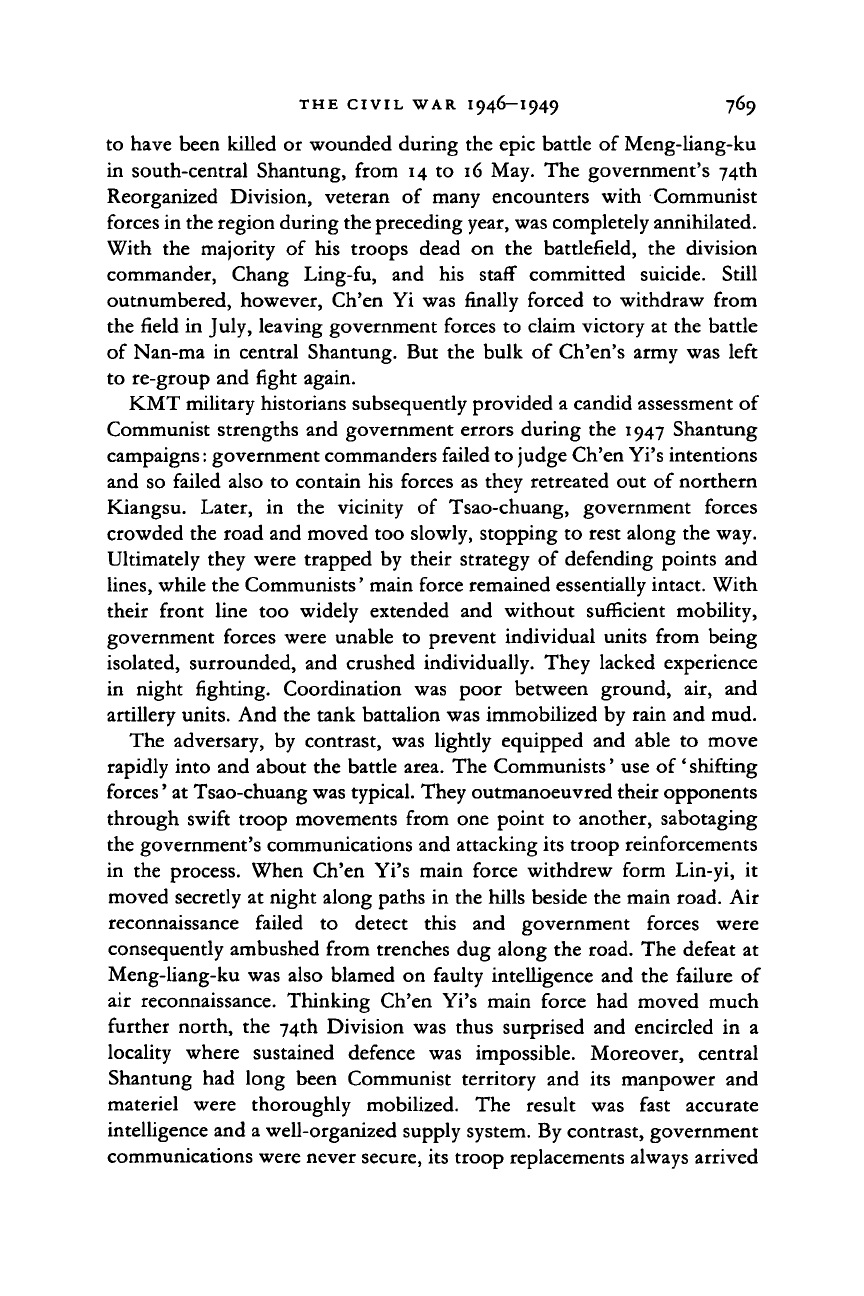

THE CIVIL

WAR

I946-I949

mill

—^

rwuuuuuvi

9

6

Communist areas

Movements of Communist forces

Movements of Nationalist forces

Great Wall

|

200 miles

'

300km

^•-

, -~

e

.-<

L

\7

-*

T'ung

^*~*~*

\

CHAHAJ/

SUIYUAN

'

J£

j /// / ,

ft"

/

SHA-NSI

^ ;

S

J

L

^ J

kuantC*^^^^^^^^^*^

SHENSI

V

u

~

..\.,

\ I

y

_,

\

i

L (

) 1

Y

1

1

I

/

*0

H U

P

E

1

-->

"v. • s.

i.\S

if U-^

Vvr

{

\

V

OPEI

A-henoting

i

^

k

1

han '

""

+/

IS

Us

r^

\

/

/

/

'

~"\\

V

IS

1

^I'engt

f

|)PEKI

r

1

•71

J

A

N

1

(

J)

1

1

<^

J^VE

1

<-"<

^_

VCH

1

V

.

%

N

\

>

^^

Tungliao

Jf^^

1

Jj^S

f

U-**Dairen

GULF

t

OF POHA

\

5 Tsingtao

-

-i i/5r^"j*short

'

r~

\

/ ;

•Changcri'un/

Lip ITtQf

^^^iS^

T^&nol

4 uonenyang)

*\

Antung^

1

<

E

L L 0

SEA

ndl

I

~jp

I

<

r\

*-S

<f>

EKIANG

f

rbi*n

A.

KinnS

"T

jr

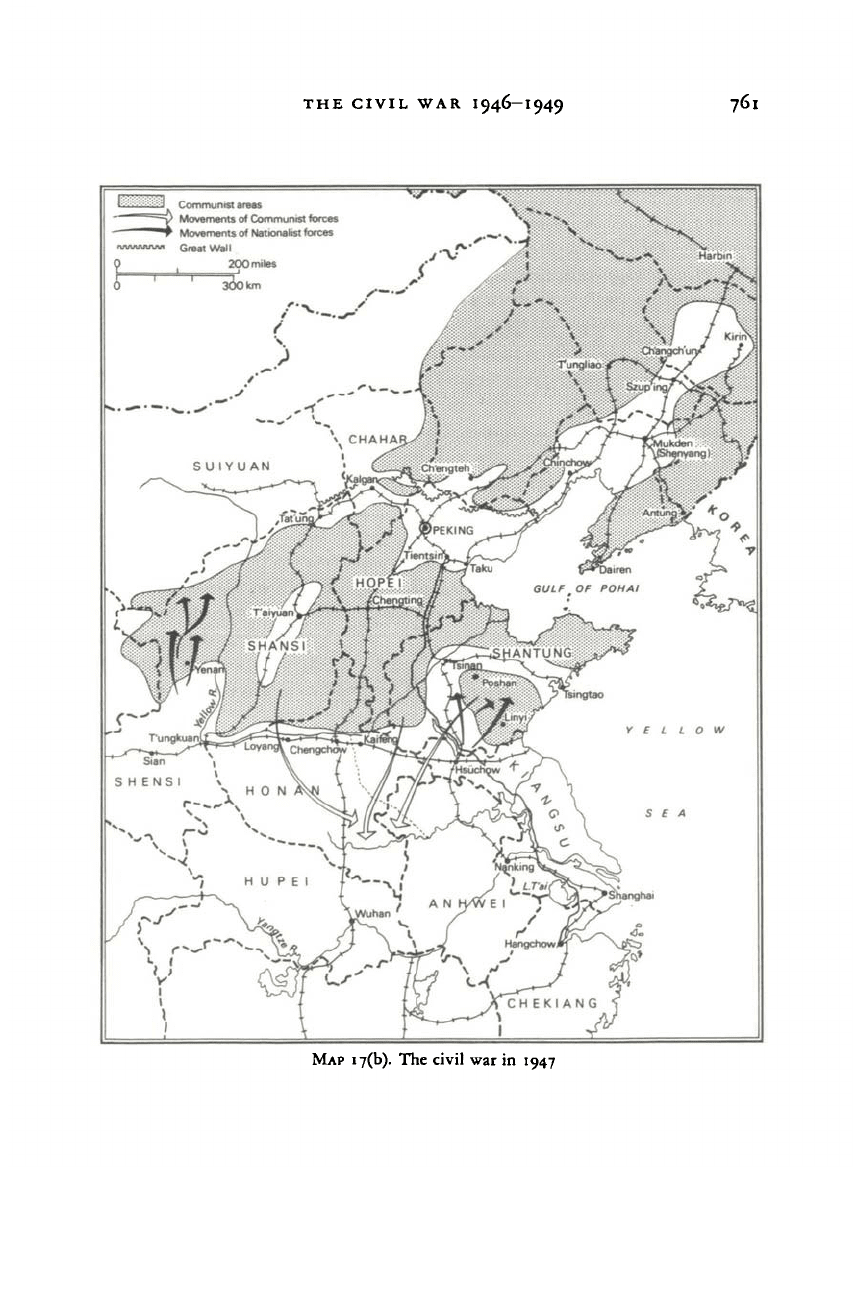

MAP

i7(b).

The

civil

war in 1947

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

762 THE KMT-CCP CONFLICT I945-I949

win,' asserted Mao. 'Acting counter

to it we

shall lose.'

50

Here

in

summary form were the operational principles which would soon become

famous.

The government offensive during the first week of July 1946 moved

to surround Communist units led by Li Hsien-nien and Wang Chen on

the Honan-Hupei border north

of

Hankow. They broke

out of

the

encirclement and made their way back

to

the Communist base area

in

Shensi. The government had eliminated the threat they posed in the area,

but the forces themselves survived to fight another day. In Shantung, the

government declared the Tsinan-Tsingtao line

to

have been cleared of

Communist forces on 17 July. But due to their continuing harassment,

railway traffic still had not resumed by the end of September. Also in July,

government units crossed the Yellow River and moved into southern

Shansi. In the eastern part of the province, however, Communist forces

were able to cut the railway line running from the capital, Taiyuan,

to

Shihchiachuang.

5

'

The July offensive in northern Kiangsu began with government forces

moving north from

the

Yangtze and east from

the

Tientsin-Pukow

railway. At the time, the Communists controlled twenty-nine counties in

the region. By the following spring, government forces had retaken all

the county seats there and county governments were being re-established

under KMT control. Everywhere, the Communists followed the principle

of withdrawing before the advance of

a

superior force. The army regulars

retreated together with most

of

the militia, the party cadres and their

families. This strategy of survival preserved their main forces but at heavy

cost.

Shansi-Hopei-Sbantung-Honan.

Documents captured by government armies

when they had entered one

of

the Communists' major base areas, the

Shansi-Hopei-Shantung-Honan Border Region (Chin-Chi-Lu-Yii),

revealed the extent of the losses suffered there. The government's gains

were both extensive and unanticipated in that region. Of the 64 counties

in the Hopei-Shantung-Honan sub-region, for example, 49 were occupied

by government forces.

Of

the

35

county seats controlled

by the

Communists there in mid-1946, 24 had also fallen by January 1947. The

CCP had not expected this. They had

to

revise their plans and began

preparing for a long-term guerrilla war. Party documents spelled out the

strategy: the Communists' regular army units and militia would remain

intact while the enemy's units were gradually being destroyed. With 80—90

50

Mao Tse-tung,' Concentrate a superior force to destroy the enemy forces one by one', Mao, SW,

4.103-7.

5I

FRUS,

1946,

10.231-3.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE CIVIL WAR I946-I949 763

per cent of his forces on the attack, Chiang Kai-shek had no source of

replacements. ' So long as we keep up our spirits and continue to destroy

Chiang's forces coming into our territory,' noted one of the documents,

'then we will not only stop the enemy's offensive, but must also change

from the defensive to the offensive and restore all of our lost area.'

52

The

strategy was sound, but exhortations were not enough to keep spirits up

during the bleak winter of 1946—7.

The principle of withdrawal as a tactic of guerrilla warfare should have

included the evacuation of the local population as well as the military and

political units, the objective being to save human life, village organization,

and the grain stores. In 1946, however, the villages were not prepared

for the reversion to guerrilla warfare conditions. As a result, cadres and

defence forces fled and unarmed peasants paid with their lives and

property while the village organizations were destroyed. As in northern

Kiangsu, local KMT-sponsored governments were quickly set up to

replace them. Following soon after came the return-to-the-village corps

{hut hsiang

fuari).

These were armed units led by landlords and others bent

on re-establishing their position. They began settling accounts of their

own, seizing back the land and grain that had been distributed by the

Communists to the peasants. Reports of revenge and retaliation

abounded.

53

The documents acknowledge that thousands of peasants were

killed in this region. Destroyed with them during only a few months was

an old Communist base area that had taken nearly a decade to build. In

districts subsequently recaptured, returning Communist forces were

cursed by the peasants for having failed to protect them. The peasants

were unwilling to restore peasant associations, form new militia units, or

even attend an open meeting, so little faith did they have in the staying

power of the Communists in such areas.

54

The plans for another long-term guerrilla war like that waged against

the Japanese did not fully materialize, however, because by May 1947 the

government's offensive had already begun to weaken. Its forces were now

spread too thinly across a vast area, unable to occupy minor keypoints

as the Japanese had been able to do at the height of their penetration of

52

Ch'u tang wei, 'Kuan-yu k'ai-chan ti-hou yu-chi chan yu chun-pei yu-chi chan te chih-shih'

(Directive on developing and preparing guerilla warfare in the enemy's rear), 20 Nov. 1946,

Kurtg-lso t'ung-hsun, ji-.ju-cbi

cban-cbtng

tbuan-bao (Work correspondence, no. 32: special issue on

guerrilla warfare), 49—50; also, Ch'u tang wei, 'Chi-lu-yu wu-ko yueh lai yu-chi chan-cheng te

tsung-chieh yu mu-ch'ien jen-wu' (A summary of the past five months of guerrilla war in

Hopei-Shantung-Honan and present tasks), 2 Feb. 1947,

Kung-tso

fung-bsun,

)2, p. 37.

» For an eyewitness account of these incidents, see Jack Belden,

China shakes the

world,

213-74.

54

'Chi-lu-yu wu-ko yueh...', 42; Kuan-yu k'ai-chan ti-hou...', 48-5

2;

and' P'an Fu-sheng t'ung-chih

tsai ti wei tsu-chih-pu chang lien-hsi hui shang te tsung-chieh fa-yen' (Statement by Comrade

P'an Fu-sheng at a joint conference of organization department heads of the sub-district party

committees), 8 March 1947, in l-cbiu-s^u-cb'i-nien sbang-pan-nien, 38.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

764 THE KMT-CCP CONFLICT I945-I949

this same region. Meanwhile, the main forces of the Communists' regular

army, still largely intact, had stopped retreating and had been able

to

launch a number of small counter-attacks. In Shantung, Communist forces

were beginning to seize the initiative, and in Manchuria they were already

engaging in limited offensives. The party was claiming that a total of ninety

enemy brigades had been destroyed nationwide and that when the figure

reached one hundred the military balance would favour the Communist

side.

55

In fact, the military balance did shift rapidly

in

1947. US military

analysts had predicted in September 1946 that the government offensive

would bog down within a few months due to overly extended communi-

cations lines which would require ever more troops to defend. These same

analysts, however, foresaw

a

protracted stalemate due

to

the superior

training and equipment

of

the government forces: foreign observers

'generally agreed that the Communists cannot win either

in

attack

or

defence

in a

toe-to-toe slugging match with National Government

forces'.

56

No one anticipated the speed and skill with which Communist com-

manders would be able to transform their anti-Japanese guerrilla experience

into campaigns of mobile warfare. The Communists were soon deploying

larger units than they had used against the Japanese to harass and destroy

their enemy's forces piecemeal while preserving and building their own

strength. Losses were replaced by integrating militia units and captured

enemy soldiers into

the

regular armies,

and by

large-scale military

recruiting campaigns that accompanied land reform

in

the Communist

areas in 1946—7. The development of Communist political power in the

countryside that was an integral part of land reform also made possible

the civilian support work necessary to sustain these military operations

in areas that had not borne the brunt of the 1946 government offensive.

The

North-east.

The earliest successful application of this strategy occurred

in Manchuria under the direction of Lin Piao, overall commander in the

North-east. His forces had been pushed north of the Sungari River by

the end of

1946,

and government troops were poised for a spring offensive

against their final objective, Harbin. But Lin then began

a

series

of

hit-and-run raids into government territory, which would allow him

to

seize the initiative in Manchuria by midsummer and culminate in decisive

" Chang Erh, 'Chiu-ko yueh yu-chi chan-cheng tsung-chieh yii chin-hou jen-wu' (A nine-month

summary of the guerrilla war and future tasks), May 1947,

Kuns-tso

funi-hsun 12

10

'« FRUS,

1946,

IO.ZJ5-6.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE CIVIL WAR I946-I949 765

victory two years later. His timing was appropriate for a strategy of

surprise and feint, since the onset of

the

bitterly cold North-eastern winter

was an unlikely season to initiate military manoeuvres. In November 1946,

when Lin Piao's forces first launched a small diversionary attack across

the frozen Sungari, the significance of their action was not apparent. After

this brief foray southwards they quickly withdrew. An estimated force

of 60,000 men crossed the river again on 6 January 1947. This time

government troops suffered heavy casualties during at least one engagement

and were able to take few prisoners before the intruders withdrew.

Government commanders were therefore apprehensive as they anticipated

a third drive, which occurred in mid-February. But it was over by the

end of the month. Lin Piao's units withdrew quickly rather than meet

a concentration of government forces, which this time refused to be

trapped as they had been during the January operations.

The fourth Communist drive across the Sungari lasted from 7 to 18

March 1947. It inflicted heavy damage on one government division and

captured large quantities of

arms

and ammunition before again retreating.

The significance of these limited military excursions was now apparent:

government forces had been weakened and, more important, their

strategic plans for the North-east disrupted. The threat to Harbin was

delayed and the Communists' position strengthened. Lin Piao then

launched his fifth drive across the Sungari in May 1947, embarking on

a well-coordinated campaign which marked the beginning of the end of

the battle for Manchuria. A force of 400,000 men participated in the

May-June operations with advances in central, southern and south-western

Manchuria. The target of the main force was Szupingkai, midway between

Manchuria's two main cities, Changchun and Mukden. During the

five-week seige of Szupingkai, the attacking Communist troops suffered

some 40,000 casualties and could not prevent the arrival of government

reinforcements sent to relieve the Szupingkai garrison. After lifting the

seige of the city on 30 June and withdrawing across the Sungari, Lin Piao

personally accepted responsibility for the tactical errors that led to the

government's defensive victory at Szupingkai.

Despite Lin's defeat, however, his North-east Field Army had gained

the initiative and would retain it until final victory the following year.

Government troops had been forced to abandon their outposts on the

north bank of the Sungari and between the river and the Changchun-Kirin

sector, advancing the front line some

15 o

miles south of its position six

months previously. The government-held cities of Changchun, Kirin and

Mukden were isolated by the destruction of their connecting railway lines,

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

766 THE KMT-CCP CONFLICT I945-I949

some of which were not restored until after the war. Government forces

suffered losses in arms, supplies, manpower, and morale from which they

also never recovered.

57

As the Communists moved on

to

the offensive

in

the North-east and

elsewhere, government armies lapsed into

a

strategy

of

static defence.

Typically they would either withdraw

too

late from over-extended

strongpoints which had ceased to have any strategic value; or they would

remain inside them behind walls and trenches leaving the initiative to their

adversary to lay seige or not as he chose. The cause of the government's

developing Manchurian debacle, according to US military analysts at the

time,

was the initial over-extension of

its

forces and the ineptitude of their

leadership, most notably that of their commander, General Tu Yii-ming.

Yet the transfer of command in the North-east to General Ch'en Ch'eng

in mid-1947, after the Communists' fifth offensive, and his removal in early

1948 after

the

sixth offensive,

did

little

to

retrieve

the

government's

declining fortunes in the region. Its forces were still superior in equipment

and training.

But it

was increasingly apparent that

the

Communists

excelled

in

strategy and tactical application, as well as morale or fighting

spirit and sense of common purpose.

The morale factor naturally had many roots. Besides the negative effects

of corruption, incompetence, and losing strategies on the KMT side was,

especially

in

the North-east, the issue

of

regionalism.

A

key goal

of

the

government's takeover in the North-east after the Second World War was

to prevent the re-emergence there

of

the semi-autonomous power base

dominated by the family of the Old Marshal, Chang Tso-lin. Consequently

the overwhelming majority of the troops sent to the area were units from

elsewhere

in

China. The government partitioned

the

three North-east

provinces into nine administrative divisions and filled virtually all the top

posts therein with outsiders. The government's local allies tended

to be

landlords and others who had collaborated with the Japanese, since these

were the only elements loyal neither to the Communists nor to the Young

Marshal, Chang Hsueh-liang, son and heir apparent

to

Chang Tso-lin.

Perhaps because

of

his continuing popularity, the Young Marshal was

kept under house arrest for his role in kidnapping Chiang Kai-shek during

the Sian incident and was removed

to a

more secure exile

on

Taiwan,

although his release had been widely expected.

57

This account

of

the early Sungari River offensives

is

based

on

the following accounts: Civil war

in China,

194J—10,

tr. Office of the Chief of Military History, US Dept. of the Army, 81-3; Military

campaigns

in

China, 1)24-19)0,

tr.

W. W. Whitson, Patrick Yang and Paul Lai, 12J-9; William

W. Whitson and Huang Chen-hsia, The

Chinese high

command:

a history of Communist military politics,

1927-71,

306-9; and FRUS, 1947, 7.26-7, 36-7, 49-50, 88-9,

130-1,

134-7, 157-9, ><><>-8. 171-3,

178—81,

192—3, 195-6, '98-9, 203, 208-12, 214-17,

240-1.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE CIVIL WAR I946-I949 767

After the Japanese surrender, initial support for the KMT in the

North-east appeared genuine according to contemporary accounts. But the

' southerners' soon wore out their welcome. Resentment created by their

discriminatory takeover policies and the venality of their officials quickly

produced a resurgence of regionalism. Regional loyalties might not have

weighed so heavily had the government's record in the North-east been

less open to criticism. People in the North-east, as in Taiwan, a region

with an even longer history of Japanese rule, were often heard to comment

that Japan had given them better government than the KMT. In

particular, the government's effort against the Communists in the region

could hardly have succeeded without the participation of local leaders.

Yet so great was the KMT suspicion of them and the power they

represented that it spurned even such aid as they were willing to offer.

Li Tsung-jen in his

Memoirs

traces this error to Chiang Kai-shek

himself,

who remained 'prejudiced against native Manchurians'. Thus a locally

formed North-east Mobilization Commission volunteered to organize a

defence force to fight the Communists. But the offer was refused, although

government commanders were never able to organize an effective local

guerrilla force themselves. General Ma Chan-shen, a cavalry officer who

had served under both the Old and Young Marshals, agreed to work with

the government and was made a deputy commander of the North-east

Command, but he

was.

never given anything to do nor any troops to lead.

Meanwhile, government commanders in the North-east were obliged to

rely on 'outsiders' as their major source of troop replacements. Due to

the failure of their recruiting drives in the North-east, government forces

had to bring replacements for their lost and damaged divisions from areas

inside China which could ill afford to lose them.

58

The Communists took full advantage of the popular resentment these

measures aroused. They avoided the central government's arrogant

attitude toward the people of the North-east and used local talent

wherever possible. Most of the surviving units from the old North-east

army of Chang Tso-lin and Chang Hsueh-liang went over to the

Communists, as did one of the latter's younger brothers, General Chang

Hsueh-szu. The Communists welcomed them as allies and allowed them

to retain their identity as a non-Communist force under the overall

command of Lin Piao. As the Communist administered areas expanded,

the North-east Field Army was able to replenish its regular units by

recruiting locally; it organized an effective second-line force of local

irregulars and mobilized more than a million civilian support workers to

serve under its logistics command.

58

Li Tsung-jen, 434; FRUS,

1947,

7.141-2, 144-5, 211-12, 232-5.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

768 THE KMT-CCP CONFLICT I945-1949

A contemporary writer summarized the Communists' successes:

It should be known that

when

the Chinese Communists pull up the railway tracks,

or bury land mines, or explode bombs, it is not the Communists that are doing

it; the common people are doing it for them. The Chinese Communists had no

soldiers in the North-east; now they have the soldiers not wanted by the central

government. The Chinese Communists had no guns; now they have the guns

the central government managed so poorly and sent over to them, and sometimes

even secretly sold to them. The Chinese Communists had no men of

ability;

now

they have the talents the central government has abandoned.

59

There could be few better examples of how poorly the KMT government

was served by its habit of disregarding popular demands and sensibilities.

Shantung. The Communists' retreat

in

the important Kiangsu-Anhwei-

Shantung sector was more difficult

to

reverse than that

in

Manchuria.

Government forces were not

as

over-extended

in

this region, and the

Communists lacked the safe sanctuary for retreat that Lin Piao enjoyed

north of the Sungari. Nevertheless, the commander of Communist forces

in east China, Ch'en Yi, used the same strategy and tactics

to

equal

advantage.

In

Shantung, Communist troops under Hsu Shih-yu were

defeated at Kao-mi in early October 1946, in a relatively large-scale action

fought

for

control

of

the Tsinan-Tsingtao railway. This was reopened

under government control and the Communists were reported

to

have

suffered some 30,000 casualties before retreating northward. Then in early

January 1947, Communist units retreating from northern Kiangsu joined

with others from central Shantung

to

counter-attack their pursuers

at

Tsao-chuang

in

southern Shantung. Government forces were defeated

with the loss of some 40,000 men and twenty-six tanks, with which the

Communists began building an armoured column of their own. Ch'en Yi

could not hold his newly-won positions, but evacuated his headquarters

in Lin-yi county town in time

to

successfully ambush part of the force

sent

to

surround him. The ensuing defeat of government forces

in

the

vicinity of Lai-wu in February cost them another 30,000 men and control

of the Tsinan-Tsingtao railway, which was again closed to through traffic.

The government's answer was a major campaign against Ch'en Yi's base

in the I-meng Mountains during April and May 1947, using some twenty

divisions, about 400,000 men, against an estimated 250,000 Communists.

But government losses were again heavy, including 15,000 men claimed

" Ch'ien Pang-k'ai, 'Tung-pei yen-chung-hsing tsen-yang ts'u-ch'eng-ti?' (What has precipitated

the grave situation

in the

North-east?), Cb'ing-tao

sbib-pao

(Tsingtao times),

19

Feb. 1948,

reprinted in Ktun-cb'a (The obsetver), Shanghai, 27 March 1948, p. 16.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE CIVIL WAR I946—1949 769

to have been killed or wounded during the epic battle of Meng-liang-ku

in south-central Shantung, from 14 to 16 May. The government's 74th

Reorganized Division, veteran of many encounters with Communist

forces in the region during the preceding year, was completely annihilated.

With the majority of his troops dead on the battlefield, the division

commander, Chang Ling-fu, and his staff committed suicide. Still

outnumbered, however, Ch'en Yi was finally forced to withdraw from

the field in July, leaving government forces to claim victory at the battle

of Nan-ma in central Shantung. But the bulk of Ch'en's army was left

to re-group and fight again.

KMT military historians subsequently provided a candid assessment of

Communist strengths and government errors during the 1947 Shantung

campaigns: government commanders failed to judge Ch'en Yi's intentions

and so failed also to contain his forces as they retreated out of northern

Kiangsu. Later, in the vicinity of Tsao-chuang, government forces

crowded the road and moved too slowly, stopping to rest along the way.

Ultimately they were trapped by their strategy of defending points and

lines,

while the Communists' main force remained essentially intact. With

their front line too widely extended and without sufficient mobility,

government forces were unable to prevent individual units from being

isolated, surrounded, and crushed individually. They lacked experience

in night fighting. Coordination was poor between ground, air, and

artillery units. And the tank battalion was immobilized by rain and mud.

The adversary, by contrast, was lightly equipped and able to move

rapidly into and about the battle area. The Communists' use of' shifting

forces' at Tsao-chuang was typical. They outmanoeuvred their opponents

through swift troop movements from one point to another, sabotaging

the government's communications and attacking its troop reinforcements

in the process. When Ch'en Yi's main force withdrew form Lin-yi, it

moved secretly at night along paths in the hills beside the main road. Air

reconnaissance failed to detect this and government forces were

consequently ambushed from trenches dug along the road. The defeat at

Meng-liang-ku was also blamed on faulty intelligence and the failure of

air reconnaissance. Thinking Ch'en Yi's main force had moved much

further north, the 74th Division was thus surprised and encircled in a

locality where sustained defence was impossible. Moreover, central

Shantung had long been Communist territory and its manpower and

materiel were thoroughly mobilized. The result was fast accurate

intelligence and a well-organized supply system. By contrast, government

communications were never secure, its troop replacements always arrived

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

77° THE KMT-CCP CONFLICT I945-I949

late,

and supplies were insufficient. 'Compared with the Communists,'

noted the military historian's account, 'all our intelligence, propaganda,

counter-intelligence and security were inferior.'

60

The second year, 1947-1948: counter-attack

At the end of summer, 1947, Mao evaluated the results of the first year

of the war and spelled out plans for the second. Chiang Kai-shek had

committed 218 of his total 248 regular brigades and had lost over 97 of

them, or approximately 780,000 men by Mao's reckoning. Mao reported

CCP losses as 300,000 men and large amounts of territory occupied by

the advancing government forces. The main task

for

the second year

would

be to

abandon the strategy

of

withdrawal and carry the fight

directly into government territory. The secondary task was to begin taking

back the areas lost during the preceding year and destroy the occupying

forces.

61

Central and North China.

In the

summer

of

1947,

the

Communists

launched the second phase

of

the war with

a

developing nationwide

counter-offensive. Liu Po-cheng, the 'one-eyed general', commander of

the Shansi-Hopei-Shantung-Honan Field Army, on 30 June dramatically

led 50,000 men across the Yellow River

in

south-western Shantung,

diverting government forces from their campaign against Ch'en Yi farther

east. While Ch'en retreated into Shantung, Liu's forces marched across

the Lunghai railway into Honan ending in a thrust 300 miles to the south,

where

he set up a

new base area

in the

Ta-pieh Mountains

on the

Hupei-Honan-Anhwei border,

the

site

of

the

old

O-Yii-Wan soviet

established in the 1920s.

In

a

related action in late August, a smaller force of 20,000 men from

Liu's army led

by

Ch'en Keng crossed the Yellow River

in

southern

Shansi, moving south into the Honan-Shensi-Hupei border area and then

linking up with Liu's columns. A month later, Ch'en Yi led part of his

East China Field Army back through south-western Shantung and into

the Honan-Anhwei-Kiangsu Border Region where they could compensate

for the movement of Liu's army out of the area. The Communists had

thus pushed the war southward into government territory in Central China

and opened

up a

new theatre

of

operations between the Yellow and

Yangtze Rivers. These initiatives brought together the forces

of

Ch'en

60

Civil war in China, 86-99; also, Military campaigns, 139-45; Whitson and Huang, 230-9; and FRUS,

'947,

7-*7>

J8-9.

68

~9> 72-3. >7'~*. *44-

61

Mao Tse-tung, 'Strategy for the second year of the war of liberation', Mao, SW, 4.141-2.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008