The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 3: Medieval Japan

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

THE PATH TO ASHIKAGA LEGITIMACY 189

In the winter of 1351-2, Tadayoshi was captured and killed, presum-

ably by poisoning on Takauji's orders. But Tadayoshi's death only

increased the anti-Takauji sentiment in the Kanto. It was not until the

spring of 1355 that Takauji, after perhaps the most destructive battle

of the civil war, in which several sections of the city were destroyed,

retook Kyoto conclusively.

Takauji died in 1358 and was succeeded as head of the Ashikaga

house and shogun by Yoshiakira, then in his twenty-eighth year. As

might be expected, the second shogun at first had trouble keeping the

Ashikaga forces in line, but the intensity of the civil war had subsided.

The most powerful shugo houses capable of opposing the Ashikaga -

the Shiba, Uesugi, Ouchi, and Yamana - had settled their differences

and had joined forces with the bakufu. Yoshiakira died in 1368, to be

succeeded by his ten-year-old son Yoshimitsu, who lived to preside

over the most flourishing era of the Muromachi bakufu.

THE PATH TO ASHIKAGA LEGITIMACY

One of the major accomplishments of the Ashikaga house was its

success in legitimizing the post of shogun within a polity still legally

under the sovereign authority of the emperor. We have already noted

that Minamoto Yoritomo, the first shogun, did not depend solely on

the title of shogun to establish his legitimacy.

14

Rather, it was the Hojo

regents who built up the importance of the title as a device through

which to exercise leadership over the bushi class. After Yoritomo's

death, the office of shogun became identified with the powers that

Yoritomo had acquired both as the foremost military leader and by

virtue of the high ranks and titles bestowed on him by the court.

Although the office of shogun never received written definition or

legal formulation, under the Ashikaga the title was recognized as giv-

ing to its recipient and holder the status of chief of the military estate

(buke no toryo), the keeper of the warriors' customary law, and the

ultimate guarantor of the land rights of the bushi class.

The concept of buke rule, in the context of the imperial tradition of

civil government, was the subject of considerable discussion in

fourteenth-century Japan. Political philosophers in both Kyoto and

Kamakura were fully aware of the issues raised by the emergence of

military rule. Godaigo's Kemmu restoration, and the long drawn-out

14 Jeffrey P. Mass, Warrior Government in Early Medieval Japan: A Study of the Kamakura

Bakufu, Shugo, and Jito (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1974). Also see his

chapter in this volume.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

190 THE MUROMACHI BAKUFU

civil war that followed, naturally stimulated attempts at special plead-

ing on both sides. One of the foremost efforts to address the issue of

imperial rule was the Jinno

shotoki,

written between 1339 and 1343 by

Kitabatake Chikafusa, a supporter of Godaigo in exile.

Chikafusa began with the premise that the

tenno

line, by means of

correct succession from the Sun Goddess, was "a transcendent source

of virtue in government, which was above criticism."

15

On the other

hand, individual emperors were accountable for their private acts and

could be criticized if their intrusion into political and military affairs

should have unfortunate results. According to Chikafusa, not even

Godaigo was above criticism. Having failed to recognize the changed

nature of the time, his appointments to office and his rewards to

courtiers and military leaders had been capricious, and the results

proved harmful to the state.

Statements justifying military rule, written from the point of view of

the buke class, were even more direct. The court aristocracy, they

claimed, had had their day and had failed. It was the destiny of the

samurai estate, through its ability

(kiryd),

to bring the state back to a

peaceful and well-administered condition. This essentially was what

Ashikaga Takauji asserted when he prayed publicly before the

Shinomura Hachiman Shrine of

Tamba.

The same premise underlines

the preamble to the Kemmu

shikimoku

of 1336.

16

Neither statement

was critical of the emperor or his court but, rather, of the maladminis-

tration of the Hojo regents. As to what constituted good government,

the obvious answer was the maintenance of peace, law, and order, a

condition in which all the people could prosper. The basic intent of the

Kemmu shikimoku was to offer guidelines on how to achieve good

government.

17

Even more philosophically explicit on what constitutes good govern-

ment is a document known as

Toji-in goisho

(Takauji's testament) and

written in 1357, though most likely not by Takauji.

18

This document

sets forth in a Confucian manner the proposition that the state

(tenka)

is not the possession of any person, neither emperor nor shogun, but

of itself and that rulers must conform to the "essence of the polity"

(tenka no

kokoro).

Within the tenka, the task of the shogun and his

followers is to ensure peace.

15 H. Paul Varley, Imperial Restoration in Medieval Japan (New York: Columbia University

Press,

1971). 16 Shigaku

kenkyu

no (April 1971): 72-97.

17 Henrik Carl Trolle Steenstrup, "Hojd Shigetoki (1198-1261) and His Role in the History of

Political and Ethical Ideas in Japan" (Ph.D. diss., Harvard University, 1977), p. 236.

18 Ibid., p. 234.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE PATH TO ASHIKAGA LEGITIMACY I91

One is struck by the pragmatic spirit of these general statements on

government and statecraft. They clearly stand on a middle ground in

placing military rule into the context of

a

polity that included both an

emperor and a large court

(kuge)

community. No model excluded the

emperor. Nor was there any thought to bring

kuge

and

buke

together

into a single ruling class. Buke remained a separate branch of the

aristocracy. The shogun, though recognized as chief of the warrior

estate, was never conceived of as a self-proclaimed or self-appointed

official. The office of shogun was an imperial appointment. Even

though the emperor personally might be a creature of the military

hegemon, having been assisted to the throne by a victorious military

leader, investiture as shogun was an act that only the emperor and his

courtiers could perform.

Political ideas of this sort were reflected in the real world. The

struggle that preceded the final Ashikaga military victory shaped the

complex interdependence between buke and kuge interests. Takauji

had depended on the imperial patent to legitimate his chastisement of

Nitta Yoshisada, his own brother, and his natural son Tadafuyu. He

had installed Emperor Komyo, who in turn had named him seii tai

shogun.

In the years that followed, the court community became al-

most totally reliant on military government to preserve its livelihood;

yet military leaders avidly competed for apparently hollow court ranks

and functionally meaningless court titles. No matter how powerful a

military hegemon, if he aspired to recognition as ruler of the entire

country, he needed more than a conquering army. He needed also a

sufficiently high court status to demonstrate publicly his right to rule.

Having settled in Kyoto, the Ashikaga house was quickly assimi-

lated into the high aristocracy, that is, into the select group of families

of third court rank and above who were known as

kugyo.

The third

shogun, Yoshimitsu, best illustrates the capacity of the Ashikaga lead-

ers to penetrate court society. Having attained the first court rank in

1380 at age twenty-two, he received successively higher appointments

until attaining in 1394 the highest court title available, that of prime

minister

(daijd

daijin).

Yoshimitsu's successive steps up the ladder of

court rank were accompanied by his adoption of

a

commensurate life-

style.

In 1378, the Ashikaga house had built a residential palace in the

grand manner at Muromachi, soon referred to as the Palace of Flowers

(Hana no gosho). This complex of buildings occupied twice the space

of the imperial palace that had been built for the emperor by Takauji

as

a

grand gesture of patronage. When in 1381 Yoshimitsu managed to

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

192

THE

MUROMACHI BAKUFU

entertain Emperor Goenyu

in his own

residence,

the

occasion

con-

firmed his status

as

kugyo.

That Yoshimitsu fully understood this

is

revealed

in his

conscious adoption

of

two

separate ciphers,

one for use

as

a

member

of the

military aristocracy

and the

other

as a

courtier.

Increasingly from this time

on, he

used

the

latter almost exclusively.

After

his

successful reconciliation

of

the

rival branches

of

the impe-

rial house

in

1392, Yoshimitsu was

in the

most exalted position

in

both

the

kuge

and the

buke worlds.

A

supreme patron

of

the

arts,

he is

best

remembered

for his

Kitayama villa

and its

centerpiece,

the

Golden

Pavilion, built between

1397 and 1407. In 1408 he

made known

his

hopes of having his son Yoshitsugu receive

a

ceremonial standing com-

parable

to

that

of

an imperial prince, thus setting

in

motion

the

rumor

that

he

intended

to

gain

for the

Ashikaga house access

to the

imperial

throne

itself. But

Yoshimitsu died shortly thereafter.

Historians continue to debate whether Yoshimitsu

did in

fact intend

to usurp

the

throne

and

whether

he

could have succeeded. There

is

not enough documentation

to

settle

the

issue

on the

basis

of

written

evidence.

The

fact that he

did not do

so

and

that his

son and

successor

Yoshimochi dissuaded

the

court from bestowing

on his

father

the

posthumous title

of

daijo-hoo

(priestly retired monarch) indicates that

an overt

act

of usurpation would have been difficult, if not impossible,

to carry

out.

But whether

or not

Yoshimitsu intended

to

displace the emperor,

he

and

his

successors

as

shogun

did

preside over

the

demise

of

the tradi-

tion of imperial rule

as it

had been

up to

that point. As Nagahara Keiji

pointed

out so

clearly,

by

this time,

the

warrior aristocracy

had ab-

sorbed

the

functions

of

the imperial government over which

the

tenno

and

the

kuge

had

presided. Yoshimitsu possessed

all the

formal rights

of rulership:

to

grant

or

withdraw holdings

in

land,

to

staff posts

in

central

and

provincial administrations, to establish central

and

provin-

cial courts,

and to

maintain

the

flow

of

taxes. Yoshimitsu

as

chief of

the buke

had

achieved

a

general takeover

of the

functional organs

of

government.

19

Can

it

then

be

said that Yoshimitsu

had

attained

the

status

of

mon-

arch?

As

shogun,

and

hence chief

of the

buke estate,

and as

prime

minister,

and

thus

the

highest-ranking official

of the

noble estate,

he

held

the

credentials of ultimate authority

in

both. Under the Ashikaga,

19 Nagahara Keiji, "Zen-kindai

no

tenno,"

in

Rekishigaku kenkyu

467 (April 1979): 37-45.

In

English,

see

Peter Amesen, "The Provincial Vassals

of

the Muromachi Bakufu,"in Jeffrey P.

Mass

and

William B. Hauser, eds., TheBakufu in Japanese

History

(Stanford,

Calif.:

Stanford

University Press, 1985),

pp.

125-6.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

SHOGUN, SHUGO, PROVINCIAL ADMINISTRATION 193

the shogun had become more powerful than any previous secular

official. But he was not sovereign, nor were his peers likely to have

permitted him to become such.

The monarchical issue is raised in yet another context. Yoshimitsu's

acceptance in 1402 of a mission from China that brought to the shogun

documents investing him as "King of Japan" and calling on him to

adopt the Ming imperial calendar. How did Yoshimitsu justify his

break with the Japanese tradition of refusing to acknowledge the sover-

eignty of a foreign country? Certainly trade was a major consideration.

But a final assessment of the encounter may not rest in the field of

trade. Tanaka Takeo, for instance, suggests that involvement in trade

with the continent was a conscious effort by Yoshimitsu to project

Japan into the mainstream of East Asian affairs, an effort to gain

recognition as a member of the wider East Asian community. Within

Japan, the shogun's successful negotiations with China became a

means to confirm the principle that as chief of the military estate, he

had full control of Japan's foreign affairs. Yoshimitsu had in fact

shielded the emperor from facing the actuality of

a

letter of investiture

from the Ming emperor. But he also made clear that the emperor need

not be troubled by diplomatic affairs in the future.

20

SHOGUN, SHUGO, AND PROVINCIAL ADMINISTRATION

It is sometimes claimed that Takauji, in his effort to attract and hold

shugo-giadc

warriors in his command, gave away resources vital to the

sustenance of his own position as shogun. But the reverse is more

likely true. By adding to the stature ofshugo as provincial administra-

tors,

he added equally to the reach of the bakufu's authority. And as

long as they worked together in a context that admitted the shogun's

primacy, the growth of

shugo

power in the provinces was to the advan-

tage of the bakufu's rule.

At the outset of

his

attack on the Hojo, Takauji depended primarily

on members of the Ashikaga house, cadet branches, and direct retain-

ers for support in the field. His first appointments to

shugo

were

picked from among house retainers like the Ko brothers and were

placed over provinces in the Kanto where the Ashikaga already had

some reliable bases. As the war spread and Takauji was widely op-

posed by rival military houses, he was obliged to name trustworthy

20 Takeo Tanaka, with Robert Sakai, "Japan's Relations with Overseas Countries," in Hall and

Toyoda,

eds.,

Japan in The

Mwromachi

Age, p. 178.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

194

THE MUROMACHI BAKUFU

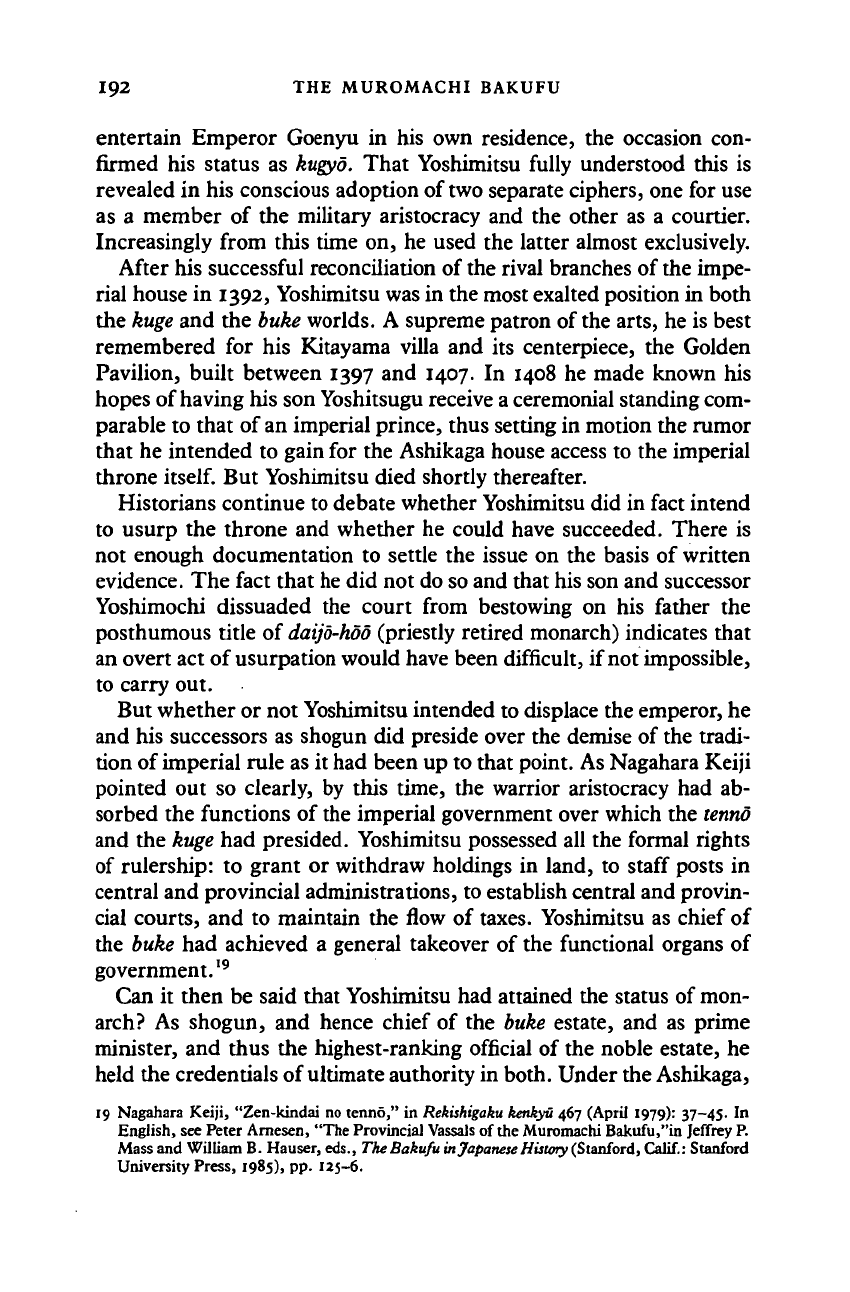

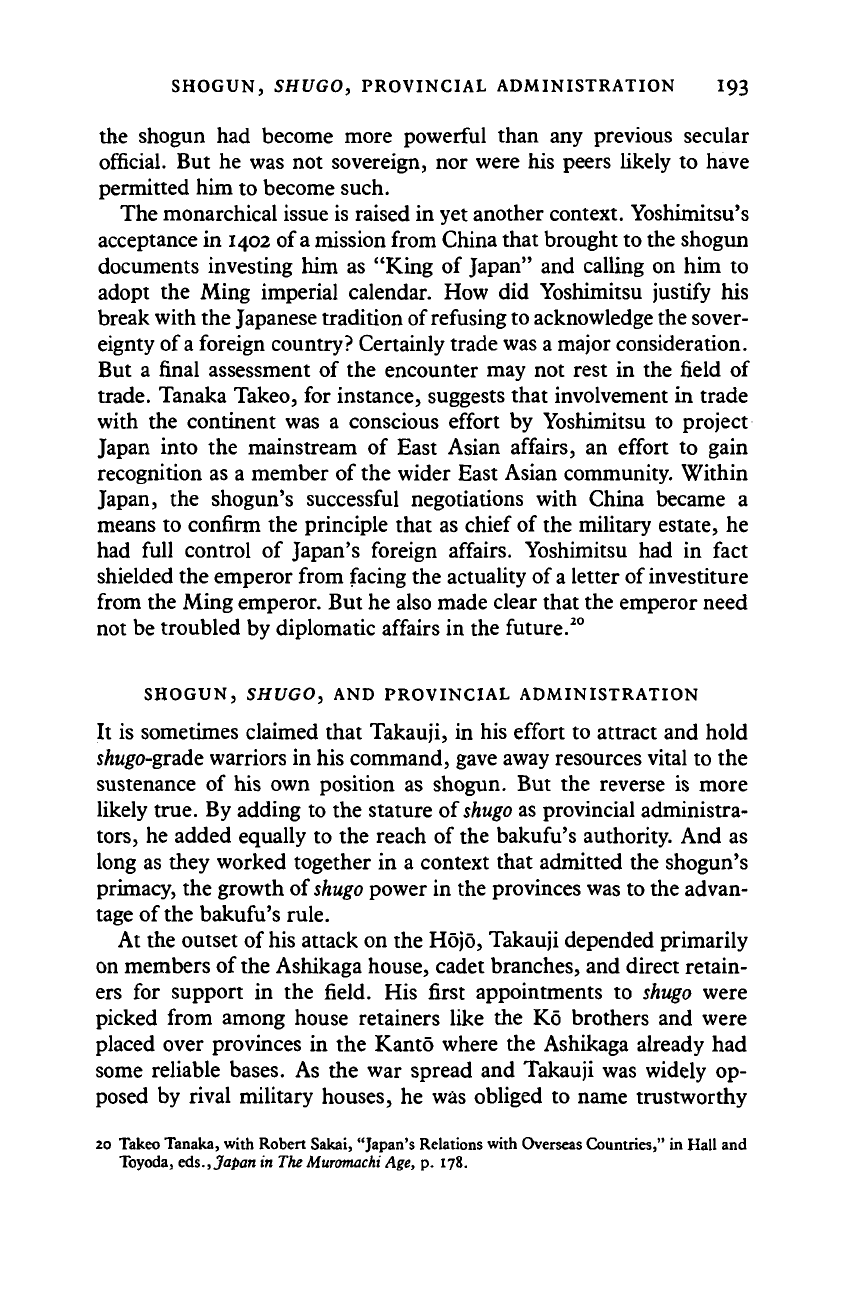

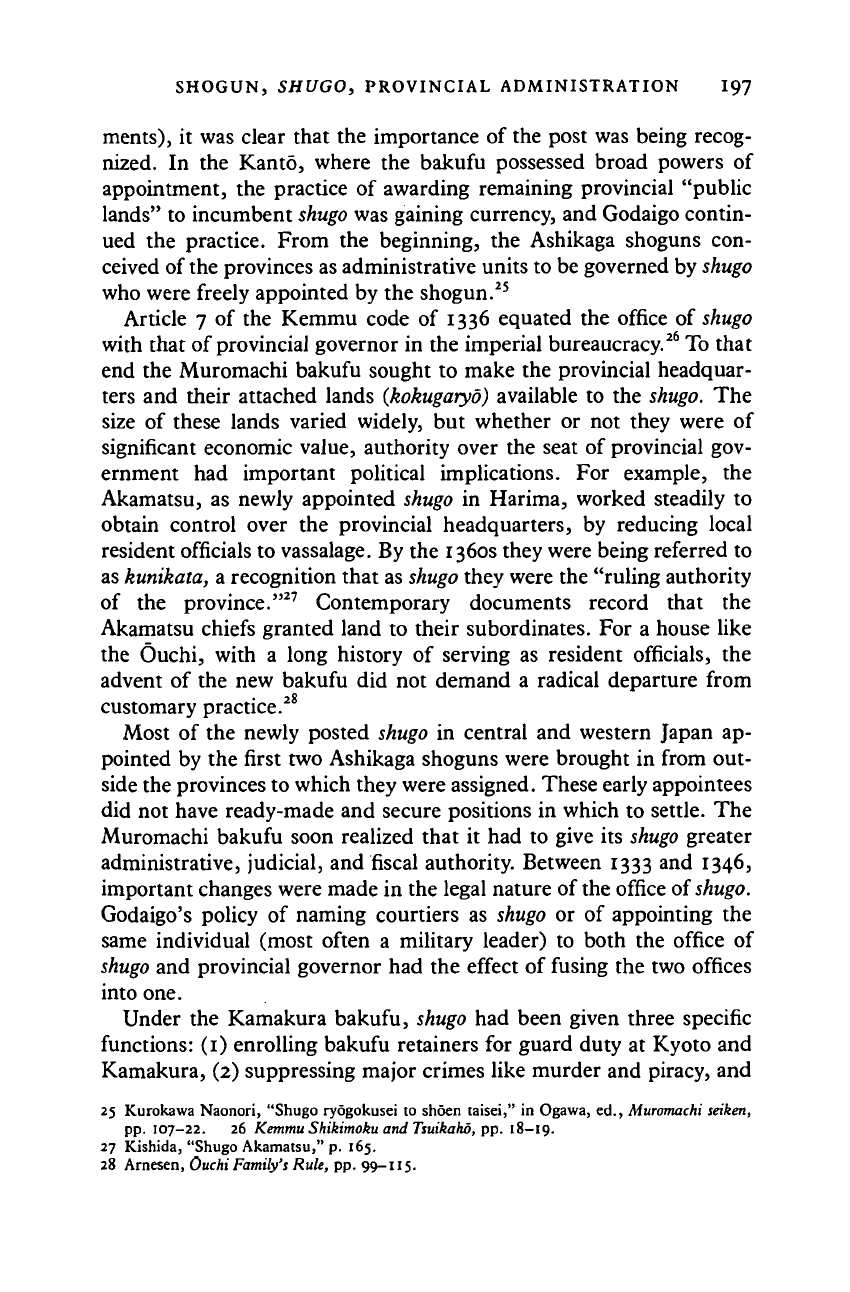

TABLE 4.2

Control of provinces by Ashikaga

collaterals

and other families, ca. 1400

Province

Yamashiro

Yamato

Kawachi

Izumi

Settsu

Iga

Ise

Shima

Owari

Mikawa

Totomi

Suruga

Omi

Mino

Hida

Shinano

Wakasa

Echizen

Kaga

Noto

Etchu

Echigo

Tamba

Family

Bakufu

Kofukuji

Hatakeyama

Niki

Hosokawa

Yamana

Toki

Toki

Shiba

Isshiki

Imagawa

Imagawa

Kyogoku

Toki

Kyogoku

Shiba

Isshiki

Shiba

Togashi

Hatakeyama

Hatakeyama

Uesugi

Hosokawa

Province

Tango

Tajima

Inaba

Hoki

Izumo

Iwami

Iki

Harima

Mimasaka

Bizen

Bitchu

Bingo

Aki

Suo

Nagato

Kii

Awaji

Awa

Sanuki

Iyo

Tosa

Family

Isshiki

Yamana

Yamana

Yamana

Kyogoku

Yamana

Kyogoku

Akamatsu

Akamatsu

Akamatsu

Hosokawa

Hosokawa

Shibukawa

Ouchi

Ouchi

Hatakeyama

Hosokawa

Hosokawa

Hosokawa

Kawano

Hosokawa

collaterals and friendly allies to all the provinces.

21

Between 1336 and

1368 the composition of the Ashikaga house band changed dramati-

cally as a number of the cadet houses who joined the Tadayoshi faction

were destroyed and as new allies were put in places of trust. Naturally

Takauji sought to bring as many provinces as possible under

shugo

appointed from among Ashikaga kinsmen. By the end of the four-

teenth century, of the provinces of central Japan, twenty-three were

held by Ashikaga collaterals, twenty by noncollaterals, and two by

institutions, as can be seen from Table 4.2" (see also Maps 4.2 and

4-3).

It is natural to assume that the collateral houses were the most

important in the eyes of the shogun. But as events proved, the

21 Imatani Akira, "Koki Muromachi bakufu no kenryoku kozo - tokuni sono senseika ni

tsuite," in Nihonshi kenkyukai shiryo kenkyu bukai ed., Chusei Nihon no rekishizo (Osaka:

Sogensha, 1978), pp. 154-183 reveals how in certain strategic but precariously held provinces

in central Japan, like Settsu, Yamato, and Izumi, shugo were appointed by kori (districts) for

strategic reasons.

22 These figures were developed from the listings of

shugo

appointments by Sugiyama Hiroshi in

Dokushi

soran

(Tokyo: Jimbutsu oraisha, 1966), pp. 115-18.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

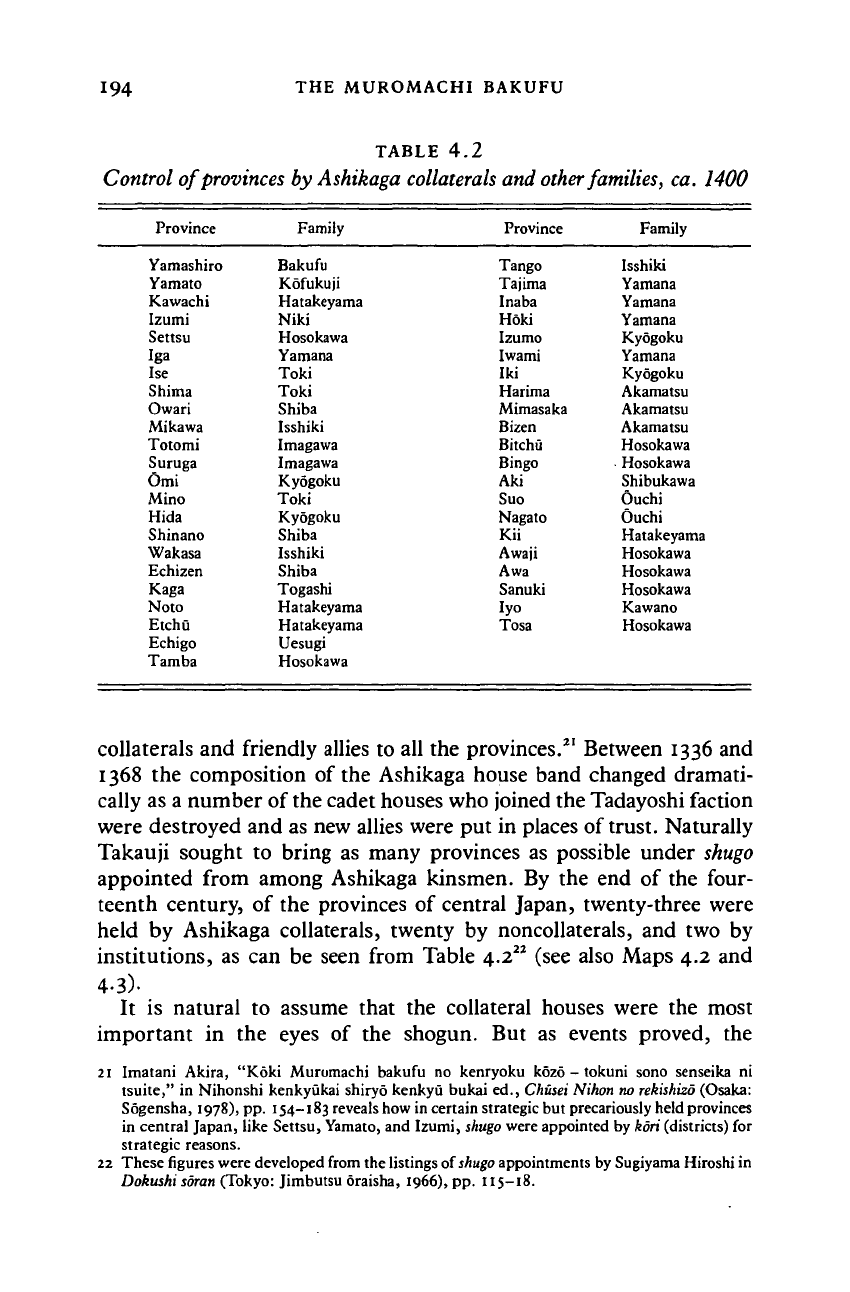

H050l<A>/A .SHIBUKT^WA.

SHIBA^

.21 gCWZEN

22.

OWA.RJ

23 SHIN^NO

Map 4.2 Provinces in central bloc held by Ashikaga collateral shugo,

ca. 1400.

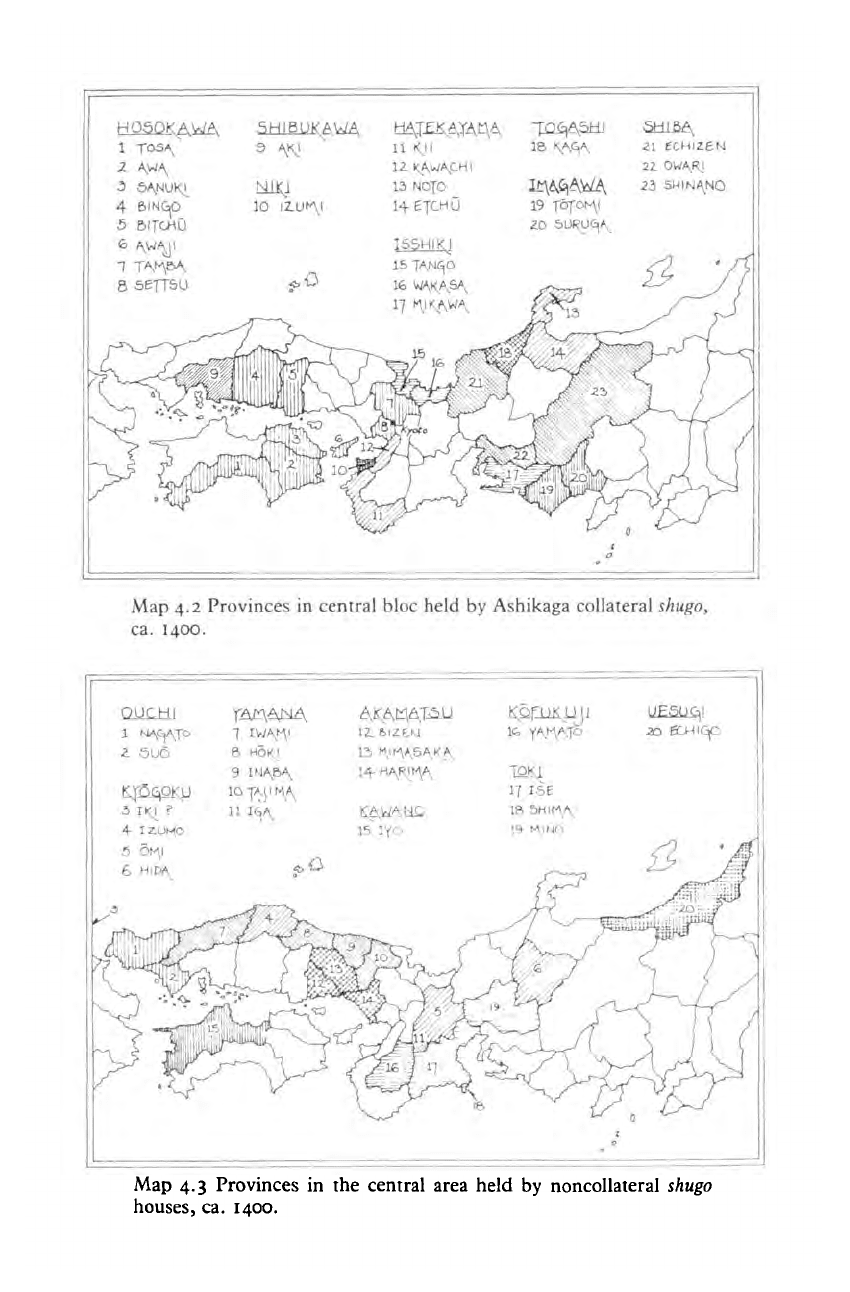

nuci-ji

1 NAfyyjo

Z. 5U6

3 riq ?

4- IZJJHP

5 ON\l

YA.^\AJ\I^

7

IWAI^I

6 HOK^I

9 IMA.BA,

10-pyiN\A^

11 1^

^^^^

nL_J_ /

i^liliiiir^v

V

A

12.

BIZEM

15

15

;<» ^%

5-<-

I /^

•~S

IS

IS

17

18

19

\"^

IS

YAtycic

(AINO

r^"—

B/

5 3D g»IGp

1 y

CTK(

IP 1>J

is

0

1*^

t

0

o

Map 4.3 Provinces in the central area held by noncollateral shugo

houses, ca. 1400.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

196 THE MUROMACHI BAKUFU

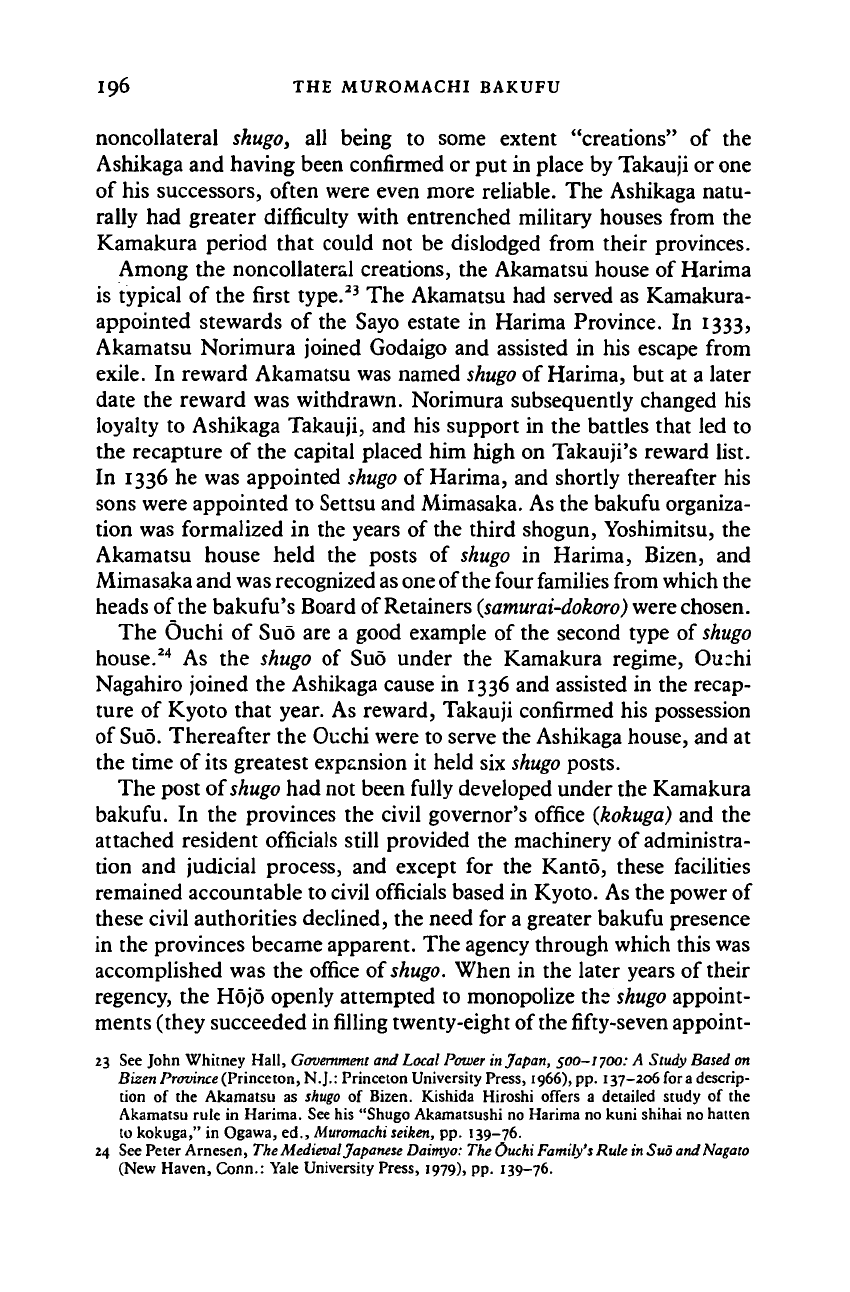

noncollateral shugo, all being to some extent "creations" of the

Ashikaga and having been confirmed or put in place by Takauji or one

of his successors, often were even more reliable. The Ashikaga natu-

rally had greater difficulty with entrenched military houses from the

Kamakura period that could not be dislodged from their provinces.

Among the noncollateral creations, the Akamatsu house of Harima

is typical of the first type.

23

The Akamatsu had served as Kamakura-

appointed stewards of the Sayo estate in Harima Province. In 1333,

Akamatsu Norimura joined Godaigo and assisted in his escape from

exile. In reward Akamatsu was named

shugo

of Harima, but at a later

date the reward was withdrawn. Norimura subsequently changed his

loyalty to Ashikaga Takauji, and his support in the battles that led to

the recapture of the capital placed him high on Takauji's reward list.

In 1336 he was appointed

shugo

of Harima, and shortly thereafter his

sons were appointed to Settsu and Mimasaka. As the bakufu organiza-

tion was formalized in the years of the third shogun, Yoshimitsu, the

Akamatsu house held the posts of

shugo

in Harima, Bizen, and

Mimasaka and

was

recognized

as one

of

the

four families from which the

heads of the bakufu's Board of Retainers

(samurai-dokoro)

were chosen.

The Ouchi of Suo are a good example of the second type of

shugo

house.

24

As the shugo of Suo under the Kamakura regime, Ou;hi

Nagahiro joined the Ashikaga cause in 1336 and assisted in the recap-

ture of Kyoto that year. As reward, Takauji confirmed his possession

of

Suo.

Thereafter the Ouchi were to serve the Ashikaga house, and at

the time of its greatest expansion it held six

shugo

posts.

The post of

shugo

had not been fully developed under the Kamakura

bakufu. In the provinces the civil governor's office

(kokuga)

and the

attached resident officials still provided the machinery of administra-

tion and judicial process, and except for the Kanto, these facilities

remained accountable to civil officials based in Kyoto. As the power of

these civil authorities declined, the need for a greater bakufu presence

in the provinces became apparent. The agency through which this was

accomplished was the office of

shugo.

When in the later years of their

regency, the Hojo openly attempted to monopolize the

shugo

appoint-

ments (they succeeded in

filling

twenty-eight of the

fifty-seven

appoint-

23 See John Whitney Hall,

Government

and Local Power

in

Japan, 500-1700: A Study Based on

Bizen Province (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1966), pp. 137-206 fora descrip-

tion of the Akamatsu as shugo of Bizen. Kishida Hiroshi offers a detailed study of the

Akamatsu rule in Harima. See his "Shugo Akamatsushi no Harima no kuni shihai no hatten

to kokuga," in Ogawa, ed.,

Muromachi

seiken,

pp. 139-76.

24 See Peter Arnesen,

The

Medieval Japanese Daimyo:

The Ouchi Family's

Rule

in

Suo and Nagato

(New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1979), pp. 139-76.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

SHOGUN, SHUGO, PROVINCIAL ADMINISTRATION I97

ments),

it was clear that the importance of the post was being recog-

nized. In the Kanto, where the bakufu possessed broad powers of

appointment, the practice of awarding remaining provincial "public

lands"

to incumbent

shugo

was gaining currency, and Godaigo contin-

ued the practice. From the beginning, the Ashikaga shoguns con-

ceived of the provinces as administrative units to be governed by shugo

who were freely appointed by the shogun.

25

Article 7 of the Kemmu code of 1336 equated the office of shugo

with that of provincial governor in the imperial bureaucracy.

26

To that

end the Muromachi bakufu sought to make the provincial headquar-

ters and their attached lands (kokugaryo) available to the shugo. The

size of these lands varied widely, but whether or not they were of

significant economic value, authority over the seat of provincial gov-

ernment had important political implications. For example, the

Akamatsu, as newly appointed shugo in Harima, worked steadily to

obtain control over the provincial headquarters, by reducing local

resident officials to vassalage. By the 1360s they were being referred to

as kunikata, a recognition that as

shugo

they were the "ruling authority

of the province."

27

Contemporary documents record that the

Akamatsu chiefs granted land to their subordinates. For a house like

the Ouchi, with a long history of serving as resident officials, the

advent of the new bakufu did not demand a radical departure from

customary practice.

28

Most of the newly posted shugo in central and western Japan ap-

pointed by the first two Ashikaga shoguns were brought in from out-

side the provinces to which they were assigned. These early appointees

did not have ready-made and secure positions in which to settle. The

Muromachi bakufu soon realized that it had to give its shugo greater

administrative, judicial, and fiscal authority. Between 1333 and 1346,

important changes were made in the legal nature of the office of shugo.

Godaigo's policy of naming courtiers as shugo or of appointing the

same individual (most often a military leader) to both the office of

shugo and provincial governor had the effect of fusing the two offices

into one.

Under the Kamakura bakufu, shugo had been given three specific

functions: (1) enrolling bakufu retainers for guard duty at Kyoto and

Kamakura, (2) suppressing major crimes like murder and piracy, and

25 Kurokawa Naonori, "Shugo ryogokusei to shoen taisei," in Ogawa, ed., Muromachi seiken,

pp.

107-22. 26 Kemmu Shikimoku and Tsuikaho, pp. 18-19.

27 Kishida, "Shugo Akamatsu," p. 165.

28 Arnesen, Ouchi Family's Rule, pp. 99-115.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

198 THE MUROMACHI BAKUFU

(3) punishing treason. In 1346, the Muromachi bakufu added two

more important powers. The first conferred the right to deal with the

unlawful cutting of crops - a favorite act of

akuto

bands. The second,

in practical terms, meant the right to carry out the bakufu's orders to

confiscate or redistribute land rights. Together, these legal provisions

gave the

shugo

the authority to exercise major judicial and fiscal pow-

ers that heretofore had been exercised by organs of

the

central govern-

ment.

29

But a number of specific military privileges were still to be

defined.

Considering the amount of warfare that accompanied the establish-

ment of the Muromachi bakufu, it is not surprising that the acquisi-

tion of supply and support resources would be a primary concern.

Those military leaders who, like Takauji or Yoshisada, commanded

large house bands, were under constant pressure to underwrite the

military expenditures of their followers. Takauji's practice was either

to dip into his own family holdings or to promise grants from future

acquisitions by conquest. Neither of these sources was fully reliable,

nor were land grants in themselves easily or quickly converted into

economic products-in-hand.

A

more immediate source of support thus

was needed. The answer was to invoke the precedent of the wartime

commissariat surtax.

It had been customary for some time for warriors in the field, or

after an extended engagement, to receive from the central authority

the right to collect commissariat rice

(hydro-mai)

from designated ar-

eas.

For example, after his victory over the Taira in 1185, Minamoto

Yoritomo was empowered to use the newly created military land stew-

ards to collect a nationwide tax of three

sho

per

tan

of cultivated land -

about a 3 percent charge on the annual harvest - for commissariat

support. When Takauji recaptured Kyoto in 1336, he issued permits

to some of his followers to collect extraordinary imposts on certain

types of land in areas in which warfare had actually taken place. These

permits were issued specifying the lands to which the tax right per-

tained as military provisions

(hyoro-ryosho).

The permits were to be

temporary. But privileges of this sort were more easily granted than

withdrawn. Before long, the taking of the "military's share" of the

country's annual product was institutionalized through the practice of

the shugo-levied half-tax (hatvzei).

The adoption of half-tax procedures illustrates the conflicting de-

mands placed on early Muromachi bakufu

policy.

The first supplemen-

29 Kurokawa, "Shugo ryogokusei,", pp. 117-19.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008