Tomlinson B.R. The New Cambridge History of India, Volume 3, Part 3: The Economy of Modern India, 1860-1970

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

AGRICULTURE,1860-I95O

43

The

sole check on landlord power under this system in its original

form

was the requirement to pay the land revenue in

full.

By this means

the Company intended to ensure

that

only capable and efficient men

would

hold the title of zamindar. Those who could not make a profit

on their estates would be sold up to make good any arrears,

thus

ensuring the survival of the fittest through the active market in land. As

it

turned

out, many existing zamindars could not work the new system

properly. Economic conditions were disturbed by depression and the

aftermath of, the great famine of

1769-70;

furthermore, the

effective

power

of many zamindars to extract

rent

from their

tenants

and to

control their

officials

was often small. Between 1794 and 1807 the lands

on which 41 per cent of the government's revenue depended changed

hands at fairly low prices, although within twenty years or so a stable

landed interest had been established, and the 'rule of property' created

in

Bengal.

As

an instrument for agricultural improvement the Permanent

Settlement was a failure. The break-up of old estates put land and

power

into the hands of smaller landlords, mainly drawn from the rural

gentry

that

had grown up around local administration, service indus-

tries and trade. While some zamindars did invest in agricultural

improvements, and in promoting new crops such as indigo, the bulk of

their income came from rents. Whereas the Bengal Government had

thought

that

the

level

of land revenue assessment would leave a profit

margin of about 10 per cent for efficient landlords, by the 1830s the

profits on estates administered by the Court of Wards were often

higher

than

the revenue demand.

18

Below

the landlords substantial

peasants and under-proprietors also profited by the control of agri-

cultural output and the manipulation of social power. Yet by the 1830s,

in many

parts

of eastern India, rural population

levels

were such

that

the bulk of cultivators were dependent on non-farm income to survive.

The

spread of high-value cash crops

that

required labour-intensive

cultivation,

such as sugar and mulberry and, to a lesser extent, indigo,

opium and even rice for urban consumption, increased demand for

labour in some areas, but the rewards of this enterprise were usually

skewed

towards those who controlled land, credit and employment.

This

was especially a problem in those areas where imports of textiles

18

Marshall,

Bengal,

p. 152.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE

ECONOMY

OF MODERN INDIA

44

had displaced local handicraft workers, thus swelling the agricultural

workforce.

Zamindari settlements, on the lines of the Permanent Settlement in

Bengal,

were imposed in other areas of central, northern and south-

western India

that

the British acquired during the early nineteenth

century.

After

1820, however, the great settlements of most of north-

western, western and southern India were conducted on a very

different basis,

that

of a new

ryotwari

system of land settlement and

taxation

that

vested control of the land in the hands of peasants (ryots),

eliminating 'parasitic' landlords and stimulating growth through direct

assessments

that

rewarded careful husbandry. The ryotwari system

required a direct, temporary settlement with the cultivator, or with a

village-level

intermediary responsible for paying rent in the past. In the

large

areas of northern India where this new system was imposed after

1820,

tenurial arrangements were made with

village

zamindars holding

pattidari rights, or with joint-owning brotherhoods (bhaiachara),

that

had the right to raise revenue before British rule. Elsewhere, notably in

western and southern India where such groups did not appear to exist,

individual

or joint settlements were made with peasant proprietors

who

claimed to have traditionally paid revenue and managed land

rights in each

village.

Under these arrangements the state became the

landlord and the cultivator or

village

proprietary body was designated

the tenant, holding a lease granted for a

fixed

period at a

fixed

rent.

Settlements were renewed, upon resurveying, at thirty-year intervals;

in the meantime proprietary and cultivating rights in land were

alienable,

and proprietors could be sold up for failure to pay their rent.

In designing the ryotwari settlements of the 1820s, 1830s and 1840s

officials

drew directly on Ricardo's theory of rent, as adapted to Indian

conditions by James

Mill,

Holt Mackenzie and

John

Stuart

Mill,

who

were

highly placed in the Company's London administration. Utili-

tarian doctrine held

that

rent was an 'unearned increment' which

represented the advantages of productivity and fertility enjoyed by

good

lands over bad. Land revenue was the state's share of this rent,

and could be

fixed

'scientifically' by careful survey and settlement

that

would

establish the product of each agricultural holding, enabling the

state to leave the cultivator enough to meet the costs of production,

subsistence and productive investment. The

level

of the revenue

demand was initially

fixed

at nine-tenths of output before 1820, then

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

AGRICULTURE,

1860-I95O

45

modified

to two-thirds in 1833. The declared aim of the ryotwari

settlements was to revitalise the rural economy by setting cultivating

peasant brotherhoods free from the depredations of corrupt state

functionaries and greedy landlords. British

officials

believed

that

abolishing

intermediaries, demanding payment of land revenue in cash,

pitching these demands at a

level

high enough to ensure

that

only the

competent survived, and creating a land market fuelled by the sale of

the assets of defaulting ryots, were all essential

parts

of this pro-

gramme. The purpose of radical reform was to overthrow an old elite

seen as enervated and non-productive, and to encourage the emergence

of

enterprising farmers who would secure a proper

return

to capital

within

the limits of

village

corporate rights. This was not to be achieved

simply

by laissez-faire, however. The Utilitarians saw an important

role for the state as the provider of social overhead capital and a

redistributor of resources, and they remained ambivalent in their

attitude to the development of rural capitalism in India. For these

reasons James

Mill

and his associates held out against

giving

private

property rights in land, and insisted on trying to regulate the rental

rate;s charged by occupancy ryots to those beneath them.

Direct

revenue assessments of this type put tremendous strains on

the administrative capacity of the Company and its British

officials.

Calculating

the 'scientific'

rent

meant careful surveys of individual

fields,

and an accurate assessment of the market rental value of the land

where no such market yet existed. Surveys and settlements

that

tried to

impose Ricardian

rent

theory in any rigorous way ran into insuperable

theoretical and practical difficulties, aggravated by the use of Indian

subordinates who had their own preferences and contacts among the

surveyed.

Thus by the 1840s the Bombay Government, for one, had

deliberately abandoned the

rent

doctrine in favour of precedent as the

basis of settlement

policy.

Even so revenue demands tended to be

cripplingly

high, and the export-oriented sectors of the agricultural

economy

suffered further from a major price depression in the late

1830s

and early 1840s. In 1838 half of the arable land in the Bombay

Deccan

was reported to be waste, while elsewhere falling prices,

collapsing

trade

and a series of financial crises led to a general

depression, which frustrated hopes

that

agricultural development

would

follow

the introduction of ryotwari principles.

The

early land settlements in

northern

and western India were later

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE

ECONOMY

OF MODERN INDIA

f>'i 'KASHMIR

1

TRAVANCORE

and COCHIN

1000km

~500 miles

k

_ _ *

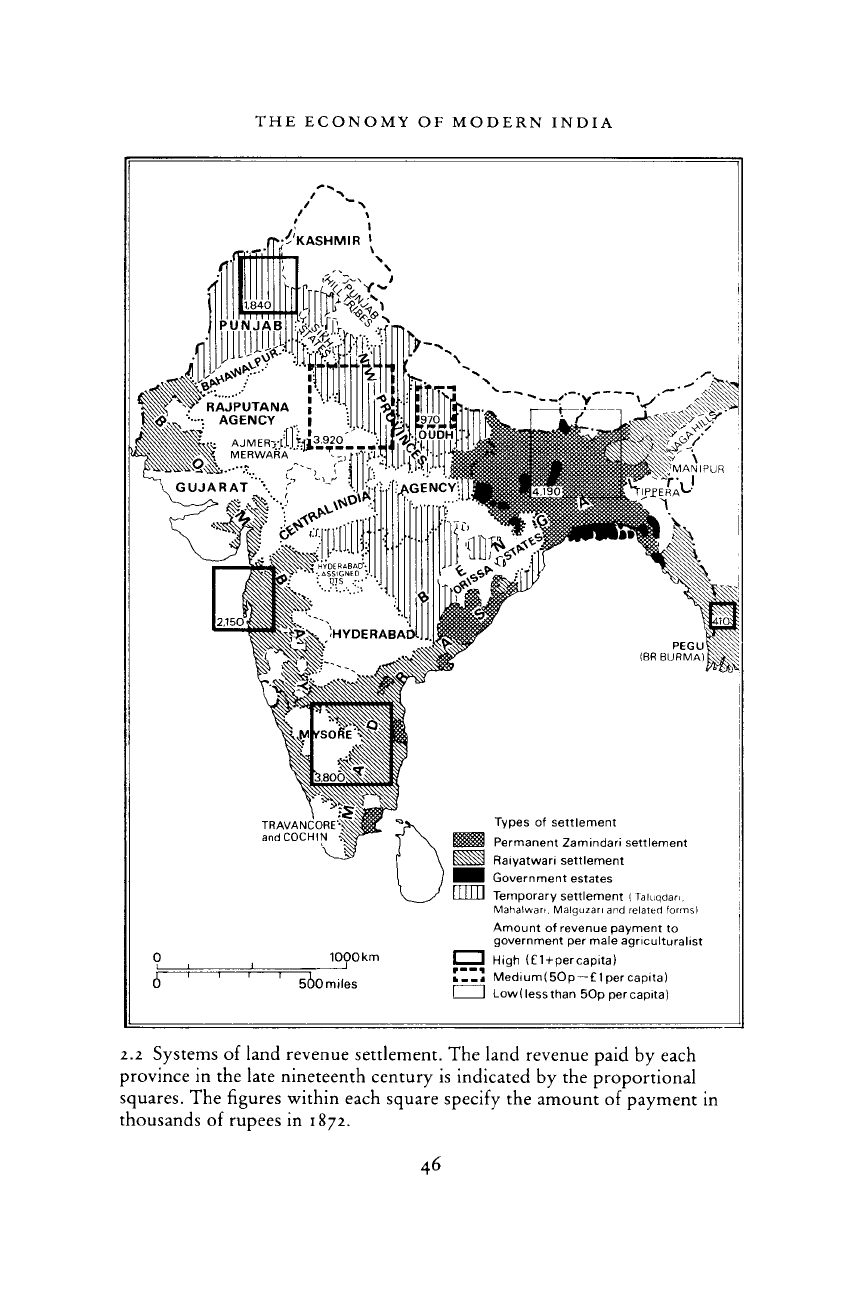

Types of settlement

Permanent Zamindari settlement

Raiyatwari settlement

Government estates

Temporary settlement

(Taiuqdan.

Mahalwan,

Malguzari and related forms)

Amount of revenue payment to

government per male agriculturalist

High

(£1

+ percapita)

Medium(50p—£1 per capita)

Low (less than 50p per capita)

2.2 Systems of land revenue settlement. The land revenue paid by each

province in the late

nineteenth

century is indicated by the proportional

squares. The figures within each

square

specify the

amount

of payment in

thousands

of rupees in 1872.

46

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

AGRICULTURE,

1860-I95O

47

widely

acknowledged to have been both onerous and inequitable. As

the Administration Report of the North-Western Provinces (later the

United

Provinces, now Uttar Pradesh) for 1882-3 confessed,

It is now generally

admitted

that

the

proportion

of the

rental

left to the

proprietors

by the old pre-1857

assessments

in the N.W. Provinces was

much

less

than

was

absolutely necessary to provide for the

support

of themselves and

their

families,

bad

debts,

expenses of

management,

and vicissitudes of season.

19

British

administrators were becoming aware of the destructive effects

of

their new administrative system by the middle decades of the

nineteenth century. Land settlements were now modified in pitch and

methodology,

with a statutory limitation of the revenue demand to

half

the rental assets laid down for the whole country in 1864. In the

Bombay

Deccan, in particular, new settlements in the 1840s based on

more sensitive criteria and a lower tax, encouraged agricultural recov-

ery

directly. However, raising adequate amounts of revenue remained

a

major concern of British land

policy,

especially as the costs of

administration rose after 1870. The main systems of land revenue

that

were

to last for the rest of the colonial period were now in place; their

geographical

coverage, and the revenue burdens associated with them,

are shown in map 2.2.

Even

with a more pragmatic approach to revenue assessment, the

ryotwari

system had a distruptive impact on rural society. The

village-level

propritors with whom the British were dealing in most

parts

of India were distinguished as holders of proprietary,

rather

than

cultivating,

rights. They represented the local elite with whom pre-

vious

rulers had made agreements to farm revenues or collect taxes.

Such

groups often reinforced their local influence by acquiring a place

in

the local administrative hierarchy, usually as

village

headmen or

village

accountants (who had the duty of registering landholdings).

These

posts in Bombay and Madras in particular, brought remunera-

tion partly through dues in cash and kind and partly through rights to

revenue-exempt

inam

land. Even in

northern

India many

village

proprietors

lived

largely on the profits of their role as local revenue and

political

managers for the state,

rather

than

from direct rental income

or agricultural production.

In most of the ryotwari areas at the time of British conquest

19

Quoted in

Eric

Stokes, The

English

Utilitarians

and

India,

Oxford,

1959,

p. 133.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE

ECONOMY

OF MODERN INDIA

possession

of government

office

remained the key to economic super-

iority

in the

village.

Like

the zamindars of

Bengal,

the

village

pro-

prietors of

northern,

western and southern India had used an implicit

licence

from the state, backed up by military leadership, kinship ties,

custom, and sometimes caste and ritual systems, to manage local

society.

But although this role had an economic function, and could

secure economic rewards, it was not based

solely,

or mainly, on

economic

criteria. Only where mamland ratios were unusually high (as

in the 'wet' irrigated regions of the great river deltas) could local

landlords exercise immediate command over agriculture by direct

control of labour through dependent tenancies. Elsewhere, the less

clear-cut

and more delicately balanced systems of

rural

social, political

and economic relations were submitted to great

strains

as a result of the

imposition of British rule. Military service was no longer an option for

most local elites and population increases diminished the shares of

proprietary rights for each inheritor. The Company's demand for

regular (and

rather

high) revenue payments was a considerable burden,

especially

in the 1830s when cash prices for agricultural produce

fluctuated

wildly.

The

village

proprietors and superior ryots with

whom

the revenue settlements were made did not necessarily control

either the marketing network inside or outside the locality, or have

access

to the liquid resources

that

were now so vital to meet

fixed

revenue payments

that

had to be paid in cash and could no longer be

renegotiated annually. As a result the

rate

of

attrition

among such

groups was quite high and

there

was a considerable volume of transfers

of

land titles, especially in

north

India.

The

creation of a land market in India in the first half of the

nineteenth century was identified by nationalist historians as one of the

most drastic effects of colonial rule

that

acted, especially in

north

India

and

Bengal,

as a mechanism for transferring control of land out of

traditional proprietors into the

hands

of merchants and moneylenders

(mahajans). As demand for export crops such as sugar, indigo and

cotton rose in the 1820s and 1830s, so the use of credit to finance

agricultural

trade

and production increased. Cash revenue payers also

borrowed extensively, especially since tax demands rarely coincided

with

harvest-times. These developments certainly

gave

merchants and

moneylenders a greatly enlarged function in the

rural

economy, and in

some

parts

of

northern

India revenue rights in up to 10 per cent of

48

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

AGRICULTURE,1860-1950

villages

changed hands, although they usually came under the control

of

service gentry groups

rather

than

traders.

20

However, the

sig-

nificance

of these developments can be exaggerated. The largest

volume

of transfers of proprietary rights took place in the confused

years before 1820. Where moneylenders and merchants did acquire

proprietary rights in the 1830s it was usually in settlement of debts, or

to secure an institutional link with

village

markets. Often such titles

were leased back to their previous holders, in

return

for a tighter

business connection. In poorer regions

there

were few rental profits to

be had, and management could not be exercised without customary

power. In the rural uprisings of 1857 the communities involved most

extensively

in the revolt were led by

village

brotherhoods

that

had

succeeded in maintaining their independence from outside incursions.

British

officials

imported much ideology and many misconceptions

to their analysis of the Indian rural economy in the first half of the

nineteenth century. Perhaps the most important and lasting of these

was

the notion

that

the Indian rural economy was made up of

self-sufficient

and self-governing

village

'republics', which required no

exchange

economy with the outside world, and were linked to it only

by

the extraction of political

tribute

in the form of taxation. This

analysis dominated nineteenth-century thinking about rural economic

development because it could be adapted to fit a wide range of

intellectual prejudices and preconceptions. To paternalists it justified

the imposition of British rule and taxation as a more

'civilised'

form of

traditional government. To radical modernizers in the British admin-

istration trained in classical political economy, especially those con-

cerned with land

rent

and revenue schemes based on Utilitarian

principles, it pointed the way forward for releasing the pent-up

energies of the Indian people, by transforming institutions, taxing the

inefficient

out of business, and creating economic incentives for

cultivators. It also provided a convenient stick with which to beat the

landlords, who could be seen as leeches sucking the surplus out of the

peasantry.

The

English Utilitarians who formulated the administrative prin-

ciples

by which the British raj was governed in the 1830s and 1840s

wanted to transform traditional India from the bottom up. Their

20

Kessinger,

'North

India',

CEHI11,

p. 264;

Stokes,

Peasant

and Raj, p. 86.

49

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE

ECONOMY

OF

MODERN

INDIA

greatest critic, Karl Marx, shared their prejudices to a large extent and

argued

that

Company rule in these decades was dissolving 'these small

semi-barbarian communities by blowing up their economical basis',

and bringing the 'greatest, and to speak the

truth,

the only

social

revolution ever heard of in

Asia'.

21

To Marx the consequences of the

social

revolution unleashed by British rule were not very happy, a

view

shared by many later conservative commentators on British policy.

This

contrast between 'traditional' village India, built around non-

material values, self-sufficiency and continuity, and the 'modern'

countryside of markets, social differentiation and rural exploitation,

continued to

haunt

analyses of South Asian agriculture throughout the

colonial

period and beyond, achieving perhaps its most pervasive

influence in the selection of community development programmes to

secure agricultural growth under the Indian five-year plans of the

1950s

and early 1960s. However, the distinction it was built on was

largely

false as we have seen, for it misinterpreted or overlooked the

large and significant continuities between 'traditional' and 'modern'

economic institutions in the Indian rural economy of the eighteenth

and nineteenth centuries.

The

staple units of analysis

that

colonial officials devised to identify

and categorise rural systems of production have now largely been

abandoned by historians of the agrarian economy. Many of those

whom

the British identified as landowners had the right to raise

taxation,

rather

than

the capacity to cultivate the soil; such land-

ownership was usually less important in giving access to scarce

resources

than

was land control, which is much harder to identify in

the aggregate. Such control was closely bound up with the working of

the rural labour and capital markets, especially the supply of credit, but

analyses of the structure and workings of these markets must go far

beyond simple categories

that

can be derived from, or applied to,

generalised data. Most disconcerting of all, perhaps, is

that

many

individual cultivating households cannot be identified unambiguously

by

the conventional labels of 'landlord',

'tenant',

'labourer', 'creditor',

'debtor', and so on. Many examples exist of household survival

strategies

that

involved a wide range of economic activities, often

21

These

phrases

occur in Marx's articles for the New

York

Daily

Tribune

published

in

1853,

cited

in

Stokes,

Peasant and Raj, p. 24.

50

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

AGRICULTURE,

1860-I95O

combining

some ownership with tenancy or sharecropping, and even

labour, and with employment in the

urban

or

rural

handicraft sector as

well

as in cultivation.

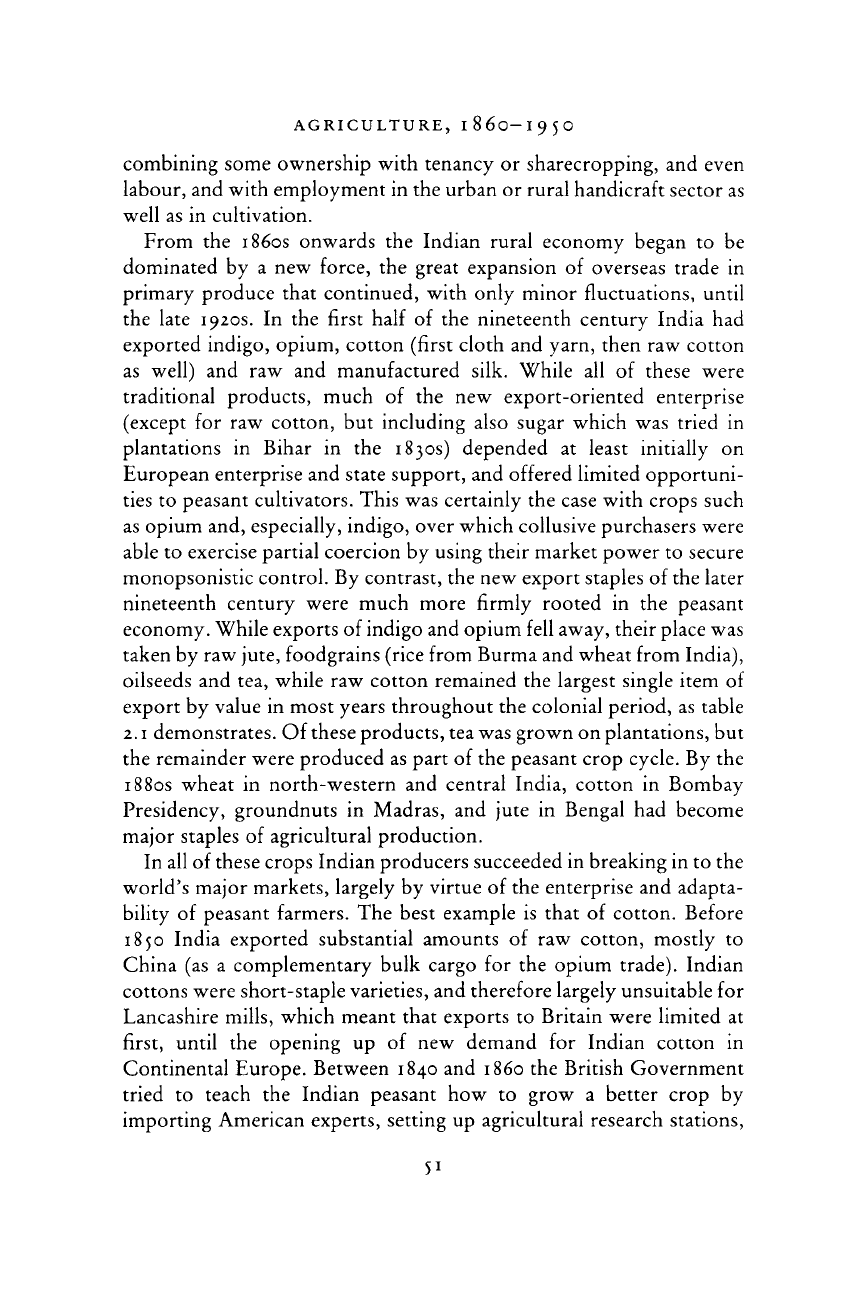

From the

1860s

onwards the Indian

rural

economy began to be

dominated by a new force, the great expansion of overseas

trade

in

primary produce

that

continued, with only minor fluctuations, until

the late

1920s.

In the first half of the nineteenth century India had

exported indigo, opium, cotton (first cloth and yarn,

then

raw cotton

as

well)

and raw and manufactured silk. While all of these were

traditional products, much of the new export-oriented enterprise

(except

for raw cotton, but including also sugar which was tried in

plantations in Bihar in the

1830s)

depended at least initially on

European enterprise and

state

support, and offered limited opportuni-

ties to peasant cultivators. This was certainly the case with crops such

as opium and, especially, indigo, over which collusive purchasers were

able to exercise partial coercion by using their market power to secure

monopsonistic control. By contrast, the new export staples of the later

nineteenth century were much more firmly rooted in the peasant

economy.

While exports of indigo and opium

fell

away, their place was

taken by raw jute, foodgrains (rice from Burma and wheat from India),

oilseeds

and tea, while raw cotton remained the largest single item of

export by value in most years throughout the colonial period, as table

2.1

demonstrates. Of these products, tea was grown on plantations, but

the remainder were produced as

part

of the peasant crop

cycle.

By the

1880s

wheat in north-western and central India, cotton in Bombay

Presidency,

groundnuts in Madras, and jute in Bengal had become

major staples of agricultural production.

In all of these crops Indian producers succeeded in breaking in to the

world's

major markets, largely by virtue of the enterprise and adapta-

bility

of peasant farmers. The best example is

that

of cotton. Before

1850

India exported substantial amounts of raw cotton, mostly to

China

(as a complementary bulk cargo for the opium trade). Indian

cottons were short-staple varieties, and therefore largely unsuitable for

Lancashire mills, which meant

that

exports to Britain were limited at

first, until the opening up of new demand for Indian cotton in

Continental Europe. Between

1840

and

i860

the British Government

tried to teach the Indian peasant how to grow a

better

crop by

importing American experts, setting up agricultural research stations,

5i

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

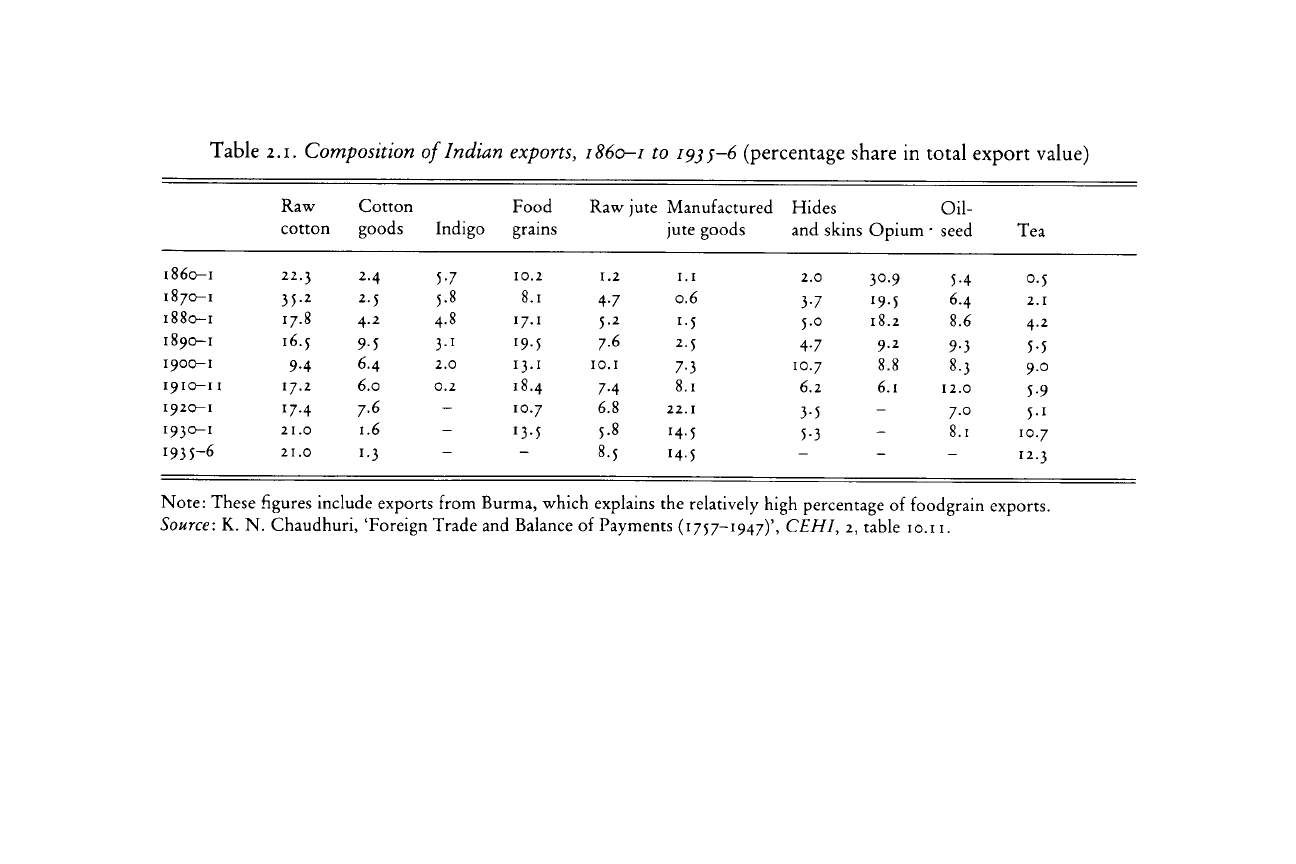

Table

2.1. Composition

of

Indian

exports, 1860-1

to

1935-6

(percentage

share

in

total export value)

Raw

Cotton

Food

Raw

jute Manufactured

Hides

Oil-

cotton

goods

Indigo

grains

jute goods

and skins Opium

'

'

seed

Tea

1860-1

22.3

2-4

5-7

10.2

1.2

1.1

2.0

30.9

5-4

0.5

1870-1

35-2

M

5.8 8.1

4-7

0.6

3-7

19-5

6.4

2.1

1880-1

17.8

4-2

4

.8

17.1

5-2

J-5

5-o

18.2

8.6

4-2

I890-I

16.5

9-5

3-

1

J

9-5

7.6

M

4-7

9-2

9-3

5-5

I900-I

9-4

6.4

2.0

13.i

10.i

7-3

10.7

8.8

8.

3

9.0

I9IO-II

17.2

6.0

0.2

18.4

7-4

8.1

6.2

6.1

12.0

5-9

I920-I

17-4

7.6

-

10.7

6.8

22.1

3-5

-

7-o

5-i

1930-1

21.0

1.6

-

5.8

14-5

5-3

-

8.1

10.7

1935-6

21.0

J

-3

8.

5

J

4-5

-

—

—

12.3

Note:

These figures include exports from Burma, which explains

the

relatively high percentage

of

foodgrain exports.

Source:

K.

N.

Chaudhuri, 'Foreign Trade and Balance

of

Payments

(1757-1947)',

CEHI,

2,

table

10.11.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008