Walsh J.E. A Brief History of India

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF INDIA

302

brought prosperity to India’s urban middle classes and were backed by

the business classes, whose support the BJP was courting. Over the next

fi ve years the BJP introduced probusiness policies that further liberal-

ized and privatized India’s economy. The government cut taxes on capi-

tal gains and dividends. It began the privatization of state-controlled

companies. It eased limits on the percentage of Indian companies that

could be controlled by foreign investors. It removed import restrictions

on more than 700 types of goods. New labor laws were proposed to

make it easier for companies to fi re employees and contract out work.

But although a commitment to improve rural water supplies, housing,

and education had been part of the BJP’s initial agenda, the party offered

reform proposals in these areas only in its 2004 (election-year) budget.

Nuclear Strategy

Although the BJP had had to give up parts of its agenda to form the

governments of 1998 and 1999, the party was determined to make good

on long-standing pledges to strengthen India militarily and as a world

CAMPAIGNS OF HATE

T

he years 1998 and 1999 saw 116 attacks against Christians in

India, more than at any time since independence. The violence

was worst in the tribal areas of Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, and Orissa.

In Orissa members of the Bajrang Dal were implicated in inciting a

mob attack that killed an Australian missionary and his two young

sons. In Gujarat attacks reached their peak during Christmas week

1998 into January 1999. A rally on December 25 in a tribal region

of southeastern Gujarat was organized by a local Hindu extremist

group. Anti-Christian slogans were shouted by 4,000 people, some

of which were recorded on tape. “Hindus rise Christians run,” the

mob shouted. “Whoever gets in our way Will be ground to dust . . .

Who will protect our faith? Bajrang Dal, Bajrang Dal.” The rally was

followed by forced conversions of Christian tribals to Hinduism and

attacks on churches, missionary schools, and Christian and Muslim

shops.

Source: Quotation from Human Rights Watch. Politics by Other Means: Attacks

against Christians in India. October 1999. Available online. URL: http://www.

hrw.org/reports/1999/indiachr/. Accessed February 10, 2010.

001-334_BH India.indd 302 11/16/10 12:42 PM

303

power. In response to Pakistan’s testing of a medium-range missile,

the government authorized the explosion of fi ve underground nuclear

tests. Pakistan immediately exploded its own nuclear device, but in fall

1998 world pressure forced both countries to declare moratoriums on

nuclear tests and to open talks on Kashmir. Again in April 1999 both

nations tested ballistic missiles in a new round of saber-rattling. By

1999 the Indian government was spending $12 billion to fund equip-

ment and salaries for 1 million people in the Indian army, navy, and air

force and an additional 1 million staff in paramilitary units.

Kargil, the Fifty-Day War

By 1999 as many as 12 militant Muslim groups were fi ghting to free

Kashmir from India’s control, most supported economically and mili-

tarily by Pakistan. Among these groups were also Kashmiri separat-

ists, groups that wanted to establish Kashmir as an independent state.

In May 1999, shepherds in the Kargil district of India’s Jammu and

Kashmir spotted armed militants (Kashmiri and Pakistani) in Pathan

dress infi ltrating the mountaintops. Two weeks later the Indian air

force and army swarmed into the region. Through all of June, Indian

forces fought to clear the intruders from the occupied mountaintops. By

July, the Indian army had driven the insurgents back across the Line of

Control drawn up by the United Nations in 1972 for a new cease-fi re in

Kashmir. Approximately 500 Indian soldiers died in the Kargil War and,

according to Indian reports, an estimated 2,000 of the enemy also died.

Indian patriotic sentiment in favor of the Kargil soldiers was extremely

high in the year following the war; soldiers’ coffi ns were displayed in

Rise (and Fall) of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)

1984 1989 1991 1996 1998 1999 2004 2009

Seats in

Lok Sabha 2 85 119 161 182 182 138 116

Percent of

national vote 7.4 11.5 20.11 20.29 25.59 23.75 22.16 18.84

Source: Hasan, Zoya, ed. Parties and Party Politics in India (New Delhi: Oxford University

Press, 2002), pp. 478–480, 509; Jaffrelot, Christophe, and Gilles Verniers. “India’s 2009

Elections: The Resilience of Regionalism and Ethnicity.” In South Asia Multidisciplinary

Academic Journal 3 (2009). Available online. URL: http://samaj.revues.org/index2787.

html. Accessed June 21, 2010.

INDIA IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY

001-334_BH India.indd 303 11/16/10 12:42 PM

A BRIEF HISTORY OF INDIA

304

public places throughout the country and in New Delhi a tribute to the

war and the dead soldiers—The Fifty Day War—was enacted for 10

days in January 2000. In 2000, the BJP increased defense spending by

28 percent, an increase justifi ed by the confl ict of the preceding year.

Gujarat Earthquake, 2001

On the morning of Republic Day (January 26), the city of Bhuj in the

Kutch region of the state of Gujarat was hit by an earthquake that

would come to be reported as the second largest in India’s recorded

history. (The largest earthquake was reported to have occurred in

1737.) The quake, caused by the release of pressure from tectonic

plate movements, was said to have measured 7.9 on the Richter scale.

It leveled 95 percent of the town of Bhuj and killed more than 12,000

people in the region of Kutch alone and as many as 20,000 people

overall. More than 1 million homes in the region were destroyed or

damaged and more than 600,000 people were left homeless. Shocks

from the quake were felt throughout northwestern India and the bor-

dering regions of Pakistan; in the commercial capital of Ahmedabad,

50 multistory buildings were said to have collapsed. Traveling in the

region in late October 2001, Narendra Modi (1950– ), an RSS pra-

charak and protégé of BJP leader Advani, now chief minister of Gujarat

as a result of a BJP state victory, urged a quick return to economic and

trade normalization.

Terrorism and Military Mobilization

On December 22, 2000, a Pakistan-based militant group attacked New

Delhi’s 17th-century Red Fort, killing one soldier and two civilians.

Almost one year later, on December 13, 2001, fi ve armed terrorists

in a car attacked New Delhi’s Parliament complex; the fi ve attackers

and seven police and staff were killed. Both attacks were believed to

have been planned by Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT), a Pakistan-based ter-

rorist group. In October 2002 Kashmiri militants killed 38 people in

Kashmir’s parliament.

Vajpayee’s government increased the Indian army presence on

Kashmir’s border, and Pakistan did the same. By 2002 the two countries

had 1 million soldiers mobilized on the border. By January 2003 each

country had expelled the other’s political envoy, and both were threat-

ening retaliation if the other side began a nuclear confl ict. If Pakistan

used nuclear weapons against India, said the Indian defense minister

George Fernandez at the time, Pakistan would be “erased from the

001-334_BH India.indd 304 11/16/10 12:42 PM

305

INDIA IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY

world map” (Duff-Brown 2003). By 2003 deaths in the Kashmir insur-

gency were estimated to have reached 38,000–60,000.

Then in 2004, as the BJP called for new elections, Prime Minister

Vajpayee called for the resumption of dialogue with Pakistan. On May

8, shortly before voting began, Vajpayee announced the restoration of

both diplomatic and transportation ties between India and Pakistan and

said a new round of peace talks would begin soon.

Gujarat Violence

The BJP distanced itself from the VHP in the election cycles that fol-

lowed the demolition and violence of the Babri Masjid campaign. The

VHP also found its activities curtailed immediately after 1992 by vari-

ous government restrictions and bans on its activities. But by the late

1990s the VHP had again returned to its earlier themes, the building

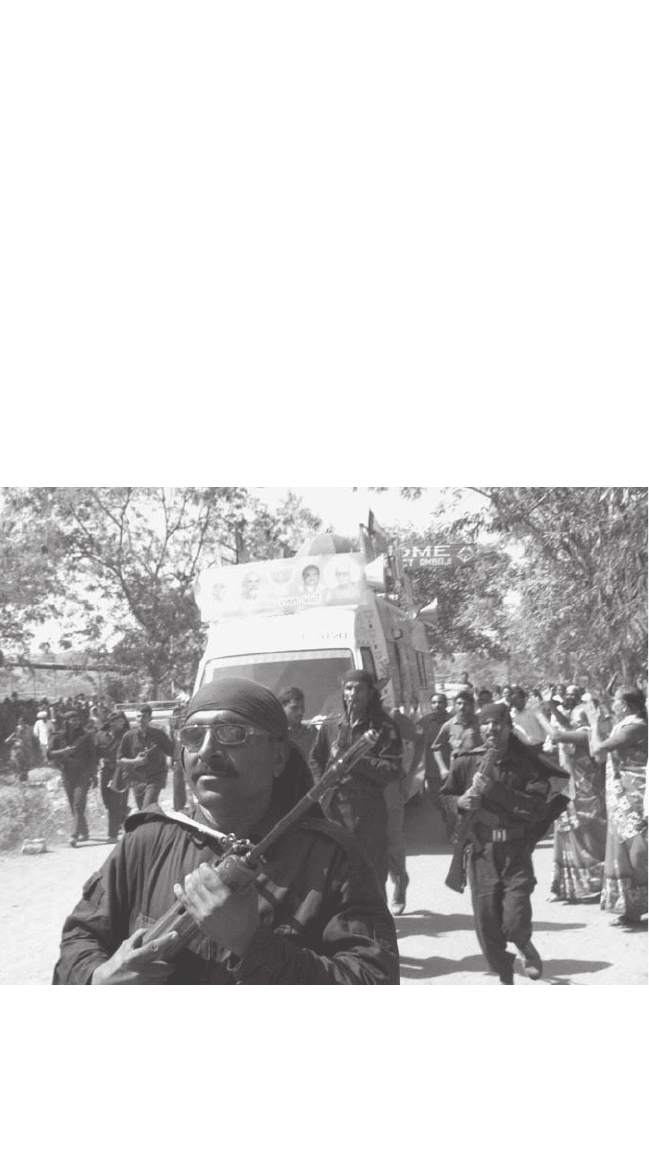

Modi’s Pride Yatra, Gujarat 2002. Black Cat Indian commandos (members of India’s elite

National Security Guard) protect Gujarat chief minister Narendra Modi’s “chariot” north of

Ahmedabad. Modi’s Pride Yatra—a procession that traveled throughout Gujarat—was part

of an election campaign calculated to appeal to Hindu nationalist sentiments in the after-

math of the state’s worst Hindu-Muslim riots since partition.

(AP/Wide World Photos)

001-334_BH India.indd 305 11/16/10 12:42 PM

A BRIEF HISTORY OF INDIA

306

of the Ram temple at Ayodhya and the dismantling of Muslim religious

structures in places such as Kashi (Benares) and Mathura.

In 2002, in the aftermath of Muslim terrorist attacks, the VHP put

forward plans for the celebration of the 10-year anniversary of the Babri

Masjid demolition. It set March 15 as the deadline for stone pillars to

be brought to Ayodhya. Although the Supreme Court ordered construc-

tion stopped two days before the deadline, activists continued to travel

between Ayodhya and the western Indian state of Gujarat (among other

places). In February 2002 a clash between Hindu volunteers returning

from Ayodhya and Muslim vendors at the Godhra rail station in Gujarat

led to the train being burned; 58 Hindus died, many women and children.

The confl ict began the worst Hindu-Muslim riots seen in India since

partition. In Gujarat more than 1,000 people died, mostly Muslims, in

violent clashes that occurred almost daily for the next several months.

The violence included rapes, murder, and burned homes. In Gujarat’s

MUSLIMS IN INDIA AFTER

PARTITION

T

he 2001 census identifi ed more than 138 million Muslims in India,

accounting for 13.4 percent of the population. Indian Muslims live

in all of India’s states and union territories but constitute a majority

in none. In northern and central interior India, rural Muslims work as

small farmers or landless laborers; in towns and cities, as artisans or

in middle- and lower-middle-class urban occupations. On the western

and southwestern coasts, in contrast, numerous prosperous Muslim

business communities and sects are found. Urdu is the fi rst language of

almost half of India’s Muslims; the rest speak regional languages such

as Assamese, Bengali, Gujarati, and Tamil, among others. Most Indian

Muslims belong to the Sunni sect of Islam.

To date, a separate Muslim personal law code from before indepen-

dence regulates Indian Muslims’ lives. This code was fi rst challenged

in 1985 by an Indian Supreme Court ruling that awarded alimony to

a divorced Muslim woman, Shah Bano Begum. Protests by orthodox

Muslims at the time forced the government to reverse the court’s

ruling and to guarantee that sharia law (orthodox Islamic customary

practices) would remain secular law for Indian Muslims. But since the

Shah Bano case Hindu nationalists have repeatedly demanded a uni-

001-334_BH India.indd 306 11/16/10 12:42 PM

307

INDIA IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY

state capital, Ahmedabad, more than 100,000 Muslims fl ed their homes

for refugee camps.

Reports suggested that police did little to stop the violence, much

of which was not spontaneous but planned and carried out under the

direction of local Hindu nationalist groups. The BJP had controlled the

Gujarat state government since 1998. It had “saffronized” (appointed

Sangh Parivar supporters to) district and regional boards and removed

an earlier prohibition against civil servants joining the RSS. The

state’s chief minister at the time was the BJP leader Narendra Modi.

Newspaper reports after the riots suggested the state had systematically

kept its Muslim police offi cers out of the fi eld and that 27 senior offi -

cers who had taken action against the rioting had been punished with

transfers. Before the Gujarat riots political observers had predicted that

the BJP’s ineffective running of the state would cost them the govern-

ment, but in the December 2002 state elections, after campaigning

form civil law code, arguing that a separate Muslim code amounts to

preferential treatment.

Communal violence is probably the single greatest concern of Indian

Muslims today, particularly in northern India. Before 1947, communal

riots were “reciprocal,” equally harming Hindus and Muslims. Since 1947,

however, riots have become more one-sided, with “the victims mainly

Muslims, whether in the numbers of people killed, wounded or arrested.”

Starting in the late 1980s and continuing to the present, Hindu national-

ist campaigns have precipitated communal violence on a scale not seen

since partition. Rioting across northern India occurred in 1990–92, in

Bombay in 1993, and in Gujarat in 2002. In the same period armed con-

fl ict between India and Pakistan over Kashmir, as well as Muslim terrorist

attacks within India itself, only compounded communal tensions.

As India’s largest and most visible religious minority, it seems likely that

Indian Muslims will remain the target of Hindu nationalist rhetoric and

agitation for the foreseeable future. The defeat of the BJP government in

2004 and 2009, however, and the rise of low-caste political movements

in the late 20th and early 21st centuries may offer poor rural and urban

Indian Muslims an alternative path to political infl uence—one that may be

used without compromising their religious identities.

Source: quotation from Khalidi, Omar. Indian Muslims since Independence (New

Delhi: Vikas, 1995), p. 17.

001-334_BH India.indd 307 11/16/10 12:42 PM

A BRIEF HISTORY OF INDIA

308

aggressively on a Hindutva platform, Modi was returned to offi ce with

a large state majority.

Elections of 2004

Prime Minister Vajpayee called for early national elections in May

2004 hoping to benefi t from the momentum of the 2003 state elec-

tions, which had produced victories for the BJP in three out of the

SONIA GANDHI STEPS FORWARD

In the years since Rajiv Gandhi left us, I had chosen to remain a

private person and live a life away from the political arena. My

grief and loss have been deeply personal. But a time has come

when I feel compelled to put aside my own inclinations and step

forward. The tradition of duty before personal considerations

has been the deepest conviction of the family to which I belong.

(Quoted in Dettman 2001)

A

lthough the Italian-born Sonia Gandhi was offered the leadership

of the Congress Party almost immediately after the assassina-

tion of her husband in 1991, she spent the six years following his death

in political seclusion, refusing to speak publicly about politics. Only at

the end of 1997, as a badly disorganized Congress was preparing to

contest the 1998 Lok Sabha elections, did Sonia Gandhi indicate her

willingness to campaign. Although Congress lost to the BJP’s coalition

in those elections, it managed to hold onto 141 seats, an accomplish-

ment many attributed to Sonia Gandhi (Frontline 1998). She became

the president of the Congress Party in May of that year and went on

to lead her party to victory in the 2004 elections. Facing a barrage

of criticism for her foreign origins, she chose not to become prime

minister after the elections, an offi ce taken instead by Manmohan

Singh. She continued as head of the Congress Party, however,

and continued to speak out on behalf of the poor and against

communalism.

Sources: Athreya, Venkatesh. “Sonia Effect Checks BJP Advance.” Frontline 15,

no. 4 (Feb. 21–Mar. 6 1998). Available online. URL: http://www.hinduonnet.

com/fl ine/fl 1504/15040060.htm. Accessed February 12, 2010; Dettman,

Paul R. India Changes Course: Golden Jubilee to Millennium (New York: Praeger,

2001), p. 9.

001-334_BH India.indd 308 11/16/10 12:42 PM

309

INDIA IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY

four contested states, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Chhattisgarh.

Congress, still the BJP’s major rival in the coalition politics of the last

20 years, had won only the state of Delhi. Campaigning for the 2004

elections the BJP focused on India’s strong (now globalized) economy,

on improved relations with Pakistan, and on its own competent gov-

ernment. The main theme of the BJP’s campaign was “India Shining,”

a media blitz on which the BJP alliance spent $20 million and which

emphasized the economic prosperity and strength India had achieved

under BJP rule. One glossy poster showed a smiling yellow-sari-clad

woman playing cricket: the caption read, “You’ve never had a better

time to shine brighter” (Zora and Woreck 2004). Later commentators

suggested that rural Indians, who had shared in little of the recent

economic growth, might have been surprised to learn that India had

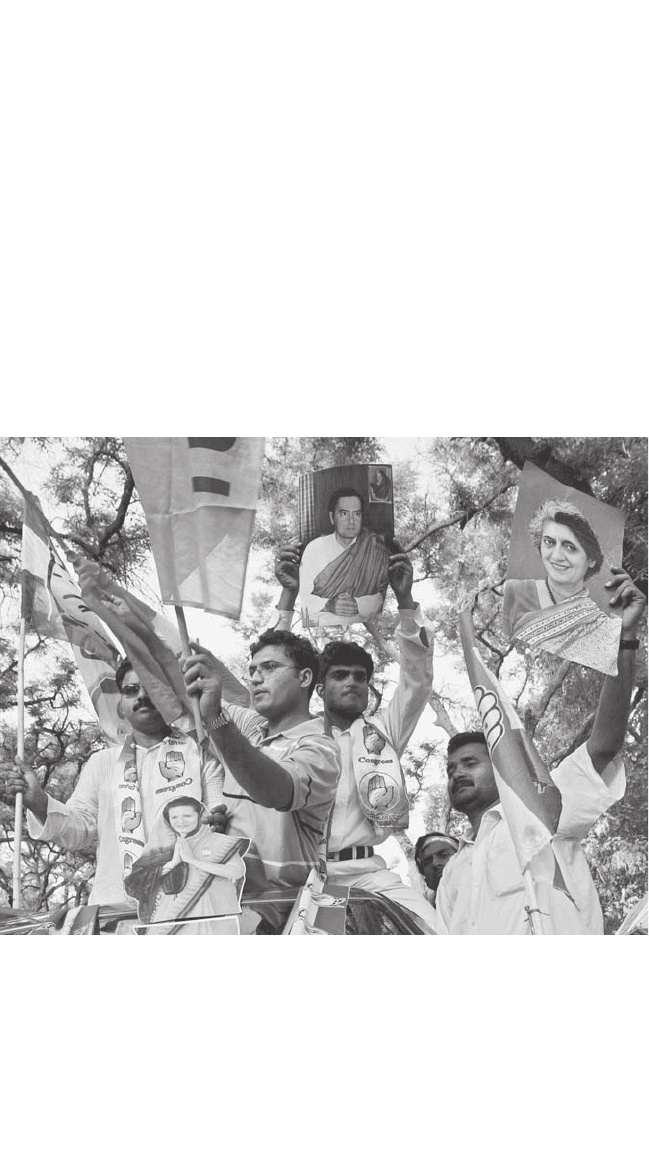

Congress victory celebration, New Delhi 2004. Jubilant Congress supporters parade images of

three Gandhis—Sonia, Rajiv, and Indira—in a victory procession following the May national

elections. But while Italian-born Sonia Gandhi was widely credited with bringing about the

Congress victory, a virulent antiforeign campaign by BJP leaders prevented her from accepting

the offi ce of prime minister. Instead Manmohan Singh, an internationally known economist

and second in authority within the Congress, became India’s prime minister.

(AP/Wide World

Photos)

001-334_BH India.indd 309 11/16/10 12:42 PM

A BRIEF HISTORY OF INDIA

310

already achieved prosperity. During the campaign Sonia Gandhi,

president of the Congress Party and widow of Rajiv Gandhi, criticized

the BJP’s waste of money on the campaign. Gandhi pointed out that

the majority of India did not share the lifestyle lauded in the BJP ads,

and she instead campaigned on a platform promising employment and

economic betterment for India’s poor.

Most political pundits predicted a BJP victory, but the party lost

badly in the 2004 elections. The BJP had, postelection, 138 Lok Sabha

seats (down from 182 in 1999) and only 22 percent of the national vote.

Meanwhile, the Congress Party, whose demise many had thought immi-

nent, won 145 Lok Sabha seats and 26 percent of the national vote. The

BJP was voted out of power in Gujarat, the state where its communal

policies had been victorious only two years before.

Approximately 390 million votes were cast in the 2004 election, 56 per-

cent of India’s 675 million registered voters. Later analyses of the Congress

victory pointed out that in India the poor vote in greater proportions

than the country’s upper and middle classes. Vajpayee, who resigned as

prime minister immediately, would later call the India Shining campaign

a major mistake. Gandhi, whose campaigning was seen as a major factor

in the Congress victory, refused to become prime minister. (BJP members

of Parliament had campaigned vigorously against the idea of a person of

Urban v. Rural Turnout in National Elections

Year of Percent of Percent of

Election Urban Voters Rural Voters

1977 61.4 57.2

1980 58.3 53.9

1984 64.0 63.0

1989 61.3 60.8

1991 53.8 56.1

1996 54.6 57.8

1998 57.7 61.5

1999 53.7 60.7

2004 53.1 58.9

Source: Based on poll data from CSDS Data Unit. Christophe, and Peter van der Veer, eds.

Patterns of Middle Class Consumption in India and China (New Delhi, Sage 2008), p. 37.

001-334_BH India.indd 310 11/16/10 12:42 PM

311

INDIA IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY

“foreign origin” holding the prime minister’s offi ce.) Instead Manmohan

Singh, the Sikh economist responsible for starting India’s globalization in

1991, became India’s fi rst non-Hindu prime minister.

The “Exceptional” Pattern of Indian Voting

In most Western democracies, the rule holds true that the higher one’s

economic bracket, the more likely one is to vote. However, as Christophe

Jaffrelot discusses in a recent article “Why Should We Vote?” (2008),

in India the reverse is true. In the 2004 U.S. election, for instance, 63.5

percent of those earning $10,000 (or less) did not vote, while only 21.7

percent of those earning $150,000 missed voting. In India, however, in

the 2004 Lok Sabha elections, the percentage of the “rich” who voted

was 56.7, while the percentage of the “very poor” who voted was 59.3.

The pattern is even more marked when comparing rural to urban voters:

In every national election since 1991, Jaffrelot notes, rural voters turned

out to vote in higher percentages than urban voters. And in urban states,

such as Delhi, the difference can be even more pronounced: In the 2003

state elections in Delhi, 60 percent of the poor and very poor voted, while

only 48.3 percent of the rich and very rich voted.

Some analysts have suggested that the rich and middle class in India

have become “disenchanted” with democracy, believing along with BJP

leader Vajpayee that “the present system of parliamentary democracy

has failed to deliver the goods” (Rediff Special 1996). India’s govern-

ment, it is suggested, has been taken over by cult leaders and mass

protests: “Strikes, shutdowns, marches, and fasts” now determine pub-

Rich v. Poor Turnout (Delhi State Elections, 2003)

Percent of Percent of

Social Class Voters Nonvoters

Very poor 60.0 40.0

Poor

Lower middle class 53.6 46.4

Middle class

Rich 48.3 51.7

Very Rich

Source: Based on poll data from 2003 state elections in Delhi. Jaffrelot, Christophe, and

Peter van der Veer, eds. Patterns of Middle Class Consumption in India and China (New

Delhi: Sage, 2008), p. 37.

001-334_BH India.indd 311 11/16/10 12:42 PM