Weingast B.R., Wittman D. The Oxford Handbook of Political Economy

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

742 economic geography

dramatically through time, and part of the economic geography story is that these

changes have been important in shaping the world economy. How are they changing

now? Some modes of interaction have become very much cheaper; falling air-freight

rates mean that around 30 per cent of US imports now go by air. However, studies

based on these data indicate an implicit willingness to pay for time saved at the rate

of around 0.5 per cent of the value of goods shipped for each day saved, indicating the

massive premium on proximity (Hummels 2001). Information and communication

technology means that some activities—those that can be digitized—can now be

shipped at essentially zero cost. However, the share of expenditure going on digitally

supplied services is extremely small, partly because once an activity is digitized it also

becomes cheap. Indeed the argument can be made that the economic importance of

distance has increased. This is because expenditure has shifted to sectors where trade

across wide distances is difficult, such as personal services, creative industries, design,

and media, all activities in which proximity and face-to-face contact are important.

What are the implications of these costs of spatial interaction for the economic

structure and income levels of remote economies? They have direct effects of increas-

ing import prices and depressing export earnings in remote economies. Impacts on

income and on the structure of activity can be derived by identifying the “market

access” of locations (Harris 1954). Recent studies take into account the fact that it is

not only market access, but also the costs of imported goods and equipment that are

important for income.

3

They find that distance-based measures of access to markets

and to suppliers are a statistically robust and quantitatively important determinant of

a country or region’s per capita income, even when other factors (such as institutions

and education) are controlled for. For example, Redding and Venables (2003)find

that halving the market access of a country—loosely interpreted as doubling the

distance between a country and its main markets—reduces per capita income by

around 25 per cent.

3 Agglomeration Mechanisms

.............................................................................

Given the cost of spatial interactions, what pattern of economic activity do we expect

to see in the world economy? The assumptions of neoclassical economics imply

that activities will be dispersed, and spread quite evenly across locations. This is

because production that is not subject to increasing returns to scale will be broken

up to supply local demands. In the limit, this is “backyard capitalism”—a little bit of

everything is produced in everyone’s backyard. Clearly, this is not a good description

of the world, and the key problem lies in the treatment of returns to scale. Only in

the presence of increasing returns is there a trade-off between producing everywhere

(low trade costs but small scale) and producing in few locations (high trade costs

³ See for example Leamer 1997; Hanson 1998; Redding and Venables 2004.

anthony j. venables 743

and low production costs). Essentially, efficiency (from the division of labor, inter

alia) is limited by the extent of the market, and the extent of the market is shaped

by geography. Once this is recognized it is possible—although not automatic—that

spatial clustering and agglomeration will occur.

3.1 Market Size and Labor Mobility

A satisfactory and tractable model of increasing returns to scale—and the concomi-

tant imperfectly competitive market structures—entered common use in economics

in the 1970sand1980s, and was taken up rapidly in industrial, international, and

spatial economics. As noted above, increasing returns to scale force firms to choose

where to locate production (as opposed to putting some production everywhere).

Rather unsurprisingly it turns out that, other things being equal, it is more profitable

to produce in a place with good market access than one with bad market access. For

example, suppose that there are two locations (countries or cities), one with a larger

population than the other, and that trade between them is possible, although costly.

The larger location then has better market access (more consumers can be accessed at

low cost) and will be the more attractive location for production. Firms are attracted

to the location, bidding up wages (and the prices of other inputs such as land) until,

in equilibrium, both locations are equally profitable but the larger one pays higher

wages. The advantages of good market access have been shifted to workers and other

factors of production.

The next stage in the argument is clear. Locations with large populations have good

market access so offer high wages; if labor is mobile, then high wages will attract

inward migration, in turn giving them large population and good market access. As

Krugman’s (1991a) “core–periphery” model showed, it is possible that two locations

are ex ante identical, but in equilibrium all activity will agglomerate in just one of

them. Positive feedback (from population to market size to firms’ location to wages

to population) creates this agglomeration force. Pulling in the opposite direction are

forces for dispersion, such as variation in the prices of immobile factors of production

(e.g. land) and the need to supply any consumers who remain dispersed. The resultant

economic geography is determined by the balance between these forces.

The story outlined above is simple, but provides an economical way of explaining

the uneven dispersion of economic activity across space. There are two key messages

that come from this and more sophisticated economic geography models. One is that

even if locations are ex ante identical, ex post they can be very different. “Cumulative

causation” forces operate so that very small differences in initial conditions can trans-

late into large differences in outcomes, as initial advantage is reinforced by the actions

of economic agents. The other message is that there is path dependence and “lock-

in.” Once established, an agglomeration will be robust to changes in the environment.

For example, a change in circumstances may mean that a city is in the “wrong place.”

However, it is not rational for any individual to move, given that others remain in the

established agglomeration.

744 economic geography

3.2 Linkages and Externalities

While the preceding sub-section outlined agglomeration mechanisms based on pop-

ulation movement, most other mechanisms are based on efficiency gains in pro-

duction. This literature dates from Marshall (1890), who described three types of

mechanism, each of which has now been developed in the modern literature.

The first is based on linkages between firms. Firms that supply intermediate goods

want to locate close to downstream customer firms (the same market size effect as we

saw in the previous sub-section) and the downstream firms want to locate close to

their suppliers. In Marshall’s words:

Subsidiary trades grow up in the neighbourhood, supplying it with implements and materials,

organising its traffic, and in many ways conducing to the economy of its material ... the

economic use of expensive machinery can sometimes be attained in a very high degree in a

district in which there is large aggregate production of the same kind ...subsidiary industries

devoting themselves each to one small branch of the process of production, and working it

for a great many of their neighbours, are able to keep in constant use machinery of the most

highly specialised character, and to make it pay its expenses.

These ideas were the subject of a good deal of attention in the development economics

literature of the 1950sand1960s, as writers such as Myrdal (1957) and Hirschman

(1958) focused on the role of backward linkages (demands from downstream firms

to their suppliers) and forward linkages (supply from intermediate producers to

downstream activities) in developing industrial activity. But as we saw above, rig-

orous treatment requires that the concepts are placed in an environment with in-

creasing returns to scale. This was done by Venables (1996), who showed how the

interaction of these linkages does indeed create a positive feedback, so tending to

cause clustering of activity. If linkages are primarily intrasectoral then there will

be clustering of firms in related activities, as described in much of the work of

Porter (1990). Alternatively, if the linkages are intersectoral then the forces may

lead to clustering of manufacturing as a whole. We return to this case in Section 4

below.

The second of Marshall’s mechanisms is based on a thick labour market:

A localized industry gains a great advantage from the fact that it offers a constant market for

skill. Employers are apt to resort to any place where they are likely to find a good choice of

workers with the special skill which they require; while men seeking employment naturally go

to places where there are many employers who need such skill as theirs and where therefore

it is likely to find a good market. The owner of an isolated factory, even if he has good access

to a plentiful supply of general labour, is often put to great shifts for want of some special

skilled labour; and a skilled workman, when thrown out of employment in it, has no easy

refuge.

In the modern literature this idea has surfaced in a number of forms. One is risk-

pooling (Krugman 1991b), as risks associated with firm-specific shocks are pooled by

a cluster of firms and workers with the same specialist skills. Another is that incentives

to acquire skills are enhanced if there are many potential purchasers of such skills,

anthony j. venables 745

avoiding the “hold-up” problem that may arise if workers find themselves faced with

a monopsony purchaser of their skills.

4

The third mechanism is geographically concentrated technological externalities:

The mysteries of the trade become no mystery; but are as it were in the air ... Good work is

rightly appreciated, inventions and improvements in machinery, in processes and the general

organisation of the business have their merits promptly discussed; if one man starts a new idea,

it is taken up by others and combined with suggestions of their own; and thus it becomes the

source of further new ideas.

This idea is applied in much of the regional and urban literature (see for example

Henderson 1974), as well as in some older trade literature (Ethier 1979), and there

is debate as to the extent to which these effects operate within or between sectors

(as argued by Jacobs 1969). It is perhaps best viewed as a black box for a variety of

important yet difficult-to-model proximity benefits.

4 Patterns of Development

.............................................................................

With these building blocks in place, we now turn to their implications for the location

of activity and for spatial disparities in economic performance.

4.1 The Great Divergence

Once these clustering forces are put in a full general equilibrium model of trade and

location, what happens, and what predictions are derived for spatial disparities? A

sweeping view of world history is provided by the model of Krugman and Venables

(1995) which studies the effects of falling trade costs on industrial location and income

levels. Their model has just two countries (North and South), endowed with equal

quantities of internationally immobile labor. There are two production sectors, per-

fectly competitive agriculture and manufacturing. Manufacturing is monopolistically

competitive, with firms operating under increasing returns to scale, and also contains

forward and backward linkages arising as firms produce and use intermediate goods

as well as producing final output.

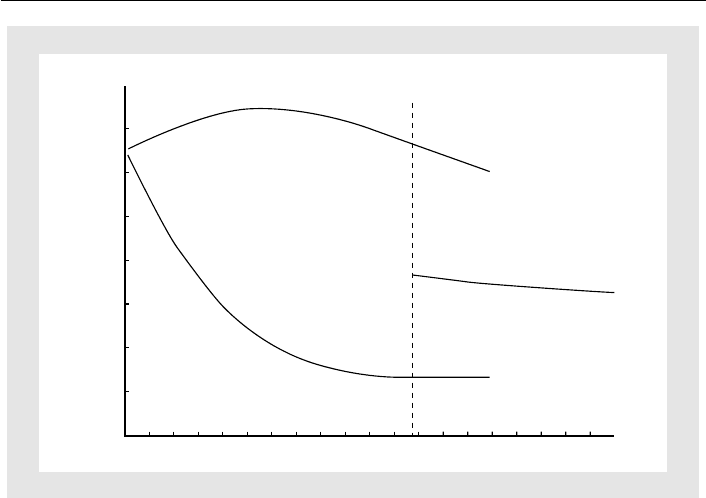

The Krugman and Venables story is summarized in Figure 41.1, which has trade

costs on the horizontal axis and real wages in North and South on the vertical axis. At

veryhightradecoststhetwoeconomieshavethesamewagerates(w

N

= w

S

), reflect-

ing the fact that they are identical in all respects. The linkages between manufacturing

firms create a force for agglomeration but when trade costs are high these are domi-

nated by the need for firms to operate in each country to supply local consumers. As

trade costs fall (moving left on the figure) so the possibility of supplying consumption

⁴ For a recent survey see Duranton and Puga 2004.

746 economic geography

Real

wages,

Trade costs

w

S

w

N

w

N

= w

S

w

N

, w

S

A

1.0 1.2 1.4 1.6 1.8

1.0

0.9

0.8

Fig. 41.1 History of the world

through trade rather than local production develops, and clustering forces become

relatively more important. At point A clustering forces come to dominate, and the

equilibrium with equal amounts of manufacturing in each country becomes unstable;

ifonefirmrelocatesfromStoNthenitraises the profitability of firms in N and

reduces the profitability of remaining firms in S, causing further firms to follow.

Four forces are at work. Two are dispersion forces: by moving to N the firm raises

wages in N and increases supply to N consumers, these forces tending to reduce

profitability of firms in N. But against this there are two agglomeration forces. A

firm that moves increases the size of the N market (the backward linkage, creating a

demand for intermediate goods). It also reduces the costs of intermediates in N (the

forward linkage, since it offers a supply of intermediates). The last two effects come

to dominate and we see agglomeration of industry in one country, raising wages as

illustrated.

5

For a range of trade costs below A, the world necessarily has a dichotomous

structure. Wages are lower in S, but it does not pay any firm to move to S as to

do so would be to forgo the clustering benefits of large markets and proximity to

suppliers that are found in N. However, as trade costs fall it becomes cheaper to ship

intermediate goods; linkages matter less so the location of manufacturing becomes

more sensitive to factor price differences. Manufacturing therefore starts to move to

S and the equilibrium wage gap narrows. In this model wage gap goes all the way to

factor price equalization when trade is perfectly free—the “death of distance.”

⁵ There is a range in which agglomeration (with w

N

>w

S

) and dispersion (with w

N

= w

S

)areboth

stable equilibria. See Fujita, Krugman, and Venables 1999 for details.

anthony j. venables 747

The model is intended to be suggestive of some of the forces driving the “great

divergence” of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Between 1750 and 1880 western

Europe’s share of world manufacturing production went from less than 20 per cent

to more than 65 per cent; together with North America, their share approached

75 per cent in the interwar period, before falling back to around 50 per cent by the

beginning of the twenty-first century. Per capita incomes diverged, and are only now

showing—for some regions—convergence. The model provides a single mechanism

that can capture both these phases. Falling transport costs in a setting in which there

are agglomeration forces in industry means that one region—the North—comes to

deindustrialize the South and create inequality in the world economy. Only once

transport costs become low enough—the globalization phase—does industry flow

back and income convergence take place.

Of course, other mechanisms are also important, and there is probably a com-

plementarity between mechanisms. Levels of education and institutional quality are

determinants of income, but are in turn determined by income. The incentives to

invest in education or develop institutions that support modern economic activity

are low in an economy that is unable to compete with imports from the Northern

manufacturing cluster.

4.2 Migration and the New World

The nineteenth century saw mass emigration from Europe to the new worlds of the

Americas and Australasia. Just one of these booming regions—the northeast of the

USA—made a successful transition from agriculture to manufacturing. Why was this

so? The historical literature gives a number of explanations, largely based around

institutional quality. Differing colonial legacies are important (North, Summerhill,

and Weingast 2000), as are the different patterns of land tenure supported by climatic

as well as colonial factors (Engerman and Sokoloff 1997). What additional and com-

plementary mechanisms are provided by new economic geography?

Once again, it is helpful to think in a very stylized way in order to draw out some

possibilities.

6

Suppose that there is an established economic center with manufactur-

ing activity (Europe) and some number of other locations (in the New World) that

can trade with the center. The new locations have high land–labor ratios, so export

primary products and import manufactures. This endowment ratio also means that

they offer high wages, attracting an inflow of migrants. The question is, at what

stage—if at all—do these new economies attract manufacturing activity? The an-

swer depends on trade costs (including tariff policies), market size, and competition

from other sources of supply. Suppose that all New World economies are identical

to each other, and all attracting immigrants at the same rate. Then there comes a

point at which the local market is large enough to support manufacturing. How-

ever, simultaneous growth of manufacturing in all of these regions is not a possible

⁶ ThisdrawsonCraftsandVenables2003.

748 economic geography

outcome—there would be oversupply of manufactures. Given the presence of ag-

glomeration forces, what happens is that if one region gets just slightly ahead (perhaps

by random chance) then cumulative causation forces take over. This region attracts

manufacturing at the expense of the others, and is the only one of the New World

regions to industrialize. The region also becomes more attractive for migrants, so

attains larger population and economic size. The world supply of manufactures is

then met by two clusters (Europe and northeast America) with the rest of the world

specialized in agriculture, as in the example of the preceding sub-section. Comparing

Argentina and the USA, North, Summerhill, and Weingast (2000) comment that “no

deus ex machina translates endowments into ...outcomes;” in this simple story one

does, and it plays dice.

Of course, this picture is oversimplified. Competing regions are not identi-

cal ex ante; market size, location, endowments, and institutions are all impor-

tant in determining the success of the modern sector. However, the insight from

the theory is that even if differences in initial conditions are small, they may

translate into large differences in outcomes. A small advantage can give a loca-

tion the advantage of being the next to start industrializing. The industrialization

processisthenrapid—a“take-off” as increasing returns and cumulative causa-

tion cut in. Furthermore, the industrialization of one New World region depresses

the prospects for others, due simply to the overall supply of manufactures in the

world economy. These other regions may experience failed industrialization, or in-

dustrialization that serves only the domestic market and remains internationally

uncompetitive.

4.3 The Spread of Industry: Globalization and Integration

We outline one further application of this line of reasoning, extending the arguments

developedabove.Asglobalizationreducestradecostsitbreaksdownsome(although

not all) of the clustering mechanisms outlined in Section 3, thereby facilitating move-

ment of industry to low wage regions. What form does this “spread of industry” take?

More or less steady convergence, with most countries catching up at a steady rate,

or alternatively rapid growth of some countries, while others stagnate? Comparison

of east Asian performance with much of the rest of the developing world seems to

support the former view, as does the empirical work of Quah (1997)pointingtothe

development of “twinpeaks” in the world income distribution—an emptying of the

low–middle range of the income distribution, as some countries grow fast and others

are left in a low-income group.

The economic geography approach to this should now be apparent, and was

formalized by Puga and Venables (1999).Lettheworldbedividedbetweencoun-

tries that have manufacturing activity and those that do not. Some growth process

is going on in the world economy—e.g. technical progress—which is raising de-

mand for manufactures. This demand growth raises wages in the economies with

manufacturing until at some point it is profitable for a firm to relocate; the cost

anthony j. venables 749

advantages of being in an existing cluster are outweighed by the higher wages this

entails. Where do firms go? If there are linkages between relocating firms then

they will cluster in a single newly emergent manufacturing country. A situation in

which all countries gain a little manufacturing is unstable; the country that gets

even slightly ahead will have the advantage, attracting further firms. Running this

process through time a sequence of countries join the group of high-income na-

tions. Each country grows fast as it joins the club, and is then followed by another

country, and so on. As before, the order in which countries join is determined by

a range of factors to do with endowments, institutions, and geography. Proximity

to existing centers may be an important positive factor, as with development in

eastern Europe and with regions of Mexico, east Asia, and China.

7

Of course, the

strict sequence of countries should not be taken literally. The key insight is that the

growth mechanism does not imply more or less uniform convergence of countries,

as has been argued by some economic growth theorists (e.g. Lucas 2000). Instead,

growth is sequential, not parallel, as manufacturing spreads across countries and

regions.

5 Urban Structures

.............................................................................

We commented earlier that economic geography insights apply at different sectoral

and spatial levels. Sectorally, it offers approaches to thinking about the location of

modern activity as a whole, and also about sectoral clusters of financial, R&D, or

industrial activities. Spatially, it provides insights for international economics, and

also for regional and urban studies. In this section we make a few remarks on the last

of these topics.

Cities can derive their existence from a spatially concentrated endowment (a port

or mineral deposit) or a spatially concentrated source of employment (a seat of

government). But for most modern cities increasing returns to scale—driven by the

agglomeration mechanisms outlined in Section 3—are a key reason for their existence

and for their success. There is considerable evidence that productivity increases with

city size, a doubling of size typically raising productivity by between 3 and 8 per cent,

although the exact mechanism through which this operates remains contentious.

8

Historically, the role of agglomeration was central to Marshall’s account of the success

of some UK cities, and David’s (1989) study of Chicago confirmed that its phenome-

nal growth was founded on agglomeration effects.

Pulling in the opposite direction have been transport costs. Transport costs be-

tween cities and rural areas reduced the market access of cities and made food

supply to large cities costly. And within cities, commuting costs take a large part of

⁷ The implications of market size and trade barriers are investigated by Puga and Venables 1999 who

assess the alternatives of export-oriented versus import-substituting manufacturing development.

⁸ See the survey by Rosenthal and Strange 2004.

750 economic geography

people’s time and expenditure and account for substantial center–edge rent gradients.

Furthermore, city transport systems are frequently congested, so that further city

growth creates negative congestion externalities for residents.

Equilibrium city size is given by the balance of these forces, when individuals are

indifferent between living in alternative locations. However, this private trade-off

between agglomeration economies and diseconomies does not, in general, create an

outcome that is socially efficient. The decision of a migrant to live and work in a

city, or of a firm making its location choice, is based on private returns and fails to

take into account external effects. New entrants to the city do not internalize either

the productivity externalities associated with city growth, or the negative externali-

ties due to congestion. In a city of a given size congestion externalities raise policy

questions for organization of transport and land use. In addition, the fact that these

are reciprocal externalities—each resident exerting effects on all others—may create

coordination failures. It is then difficult to establish new cities or to regenerate city

districts, since there is no incentive for a single small economic agent to move into a

low-rent area.

The presence of these market failures raises important questions about city gov-

ernance. One important strand of literature argues that the externalities can all be

internalized by “private government.” This government is provided by large devel-

opers who develop land, receiving the payoff from city development in the form of

land rent. It turns out that if there is a competitive supply of such developers then

the equilibrium that they support is socially efficient. Rents just cover the subsidies

that are required to align private incentives with public ones—the “Henry George”

theorem (Stiglitz 1977). However, it seems unlikely that there are many situations in

which large developers play this role. Even in countries where such developers have a

significant presence they are typically tightly circumscribed. An efficient outcome can

also be achieved by city governments that are able to tax 100 per cent of land rents,

and in which incumbent city residents vote on subsidy and tax payments in a way

that internalizes externalities. However, these results are typically dependent on the

tax instruments available and on cities’ ability to borrow in perfect capital markets

(Henderson and Venables 2004).

These issues are of importance in countries with established urban structures,

where they are typically manifest in the contexts of urban regeneration, suburban

sprawl, and the development of transport systems. They are vastly more important

in developing countries, where urban population is projected to increase by some

2 billion in the next thirty years. Will this population all go into existing mega-

cities or can new cities be developed? Reciprocal externalities mean that a new

city may be difficult to establish; initial residents do not reap benefits of scale in

the short run and may also be uncertain about the long-run prospects of a new

town. In this case mega-cities may expand vastly beyond the size that is socially

efficient.

Much work remains to be done on the design of economic policy in these sit-

uations. The political economy of implementing it, and in particular the extent to

anthony j. venables 751

which fiscal responsibility and decision-taking should be centralized or devolved,

then becomes crucial.

9

6 Conclusions

.............................................................................

Ideas from new economic geography provide a different lens through which to view

many aspects of the world economy. We suggest that there are several main messages

for students of political economy.

First, the literature suggests that spatial disparities are a normal economic out-

come. These disparities show up in different ways. If labor is fully mobile then income

differences will be eliminated but activity will have a spatially lumpy distribution as

population becomes concentrated in cities. If labor is immobile the disparities may

be manifested through spatial income inequalities. Thus, the approach provides a

rigorous analytical foundation for notions of “core” and “periphery” in the world

economy, as put forward by other writers (e.g. Wallerstein 1974). Of course, the

approach does not claim to be the only mechanism supporting such inequalities.

Endowments of human and physical capital and of natural environment matter, as

does the quality of institutions, emphasized in the work of North (1990), Acemoglu,

Johnson, and Robinson (2001, 2002), and others.

The second message is cumulative causation. If increasing returns to scale are

spatially concentrated then we expect to see regions with small initial advantages

performing substantially better than other regions. There is path dependence so that,

once established, the advantages of these cities, regions, or countries are relatively

difficult to overtake. New economic geography offers an economic basis for cumula-

tive causation and, once again, this mechanism is complementary to others based on

political economy and institutional inertia. The incentives to develop education and

business-friendly institutions are greater in regions where economic opportunities

are larger, while the development of education and institutions are themselves self-

reinforcing processes. Conversely, bad institutions may restrict interaction with the

world economy, increasing a country’s economic remoteness. Interactions between

these mechanisms, all of them operating in a cumulative rather than a linear man-

ner, means that it is difficult—and possibly futile—to seek to quantify the relative

importance of each.

Third, this view of the world suggests that externalities, arising from the ag-

glomeration mechanisms outlined in Section 3, are all pervasive. Individually they

are small—no one individual has a great effect on the productivity of his urban

⁹ See Helsley 2004 for a survey of urban political economy. There is a substantial literature on fiscal

federalism (see the survey by Rubinfeld 1988) although this is typically based in simple environments

without the returns to scale and externalities that are crucial to understanding cities and regional

disparities.