West B.A., Murphy F.T. A Brief History of Australia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF AUSTRALIA

120

Not long after the AAPA folded in New South Wales, the last

recorded mass murder of Aboriginal people in Australia took place in

the Northern Territory, near Alice Springs. This event is today known

as the Coniston Massacre. It began as a series of “punitive expeditions”

against the Warlpiri people led by Mounted Constable George Murray

reginaLd waLter saunders

w

hile this period was very difficult for many Aboriginal people

in Australia, a few individuals were able to rise above the insti-

tutional racism. One such person was Reginald Saunders, Australia’s

first Aboriginal commissioned military officer. Saunders joined the

Australian Imperial Force (AIF) in April 1940, soon after Australia

entered World War II, and was quickly identified as a natural leader.

Within six weeks he was promoted to lance corporal; three months

later he was a sergeant.

Saunders was sent first to Libya and then to Greece, withdrawing

to Crete in July 1941. When the allies were forced to evacuate Crete,

leaving behind several hundred troops, Saunders was driven into hid-

ing for almost a year. His dark complexion, however, enabled him to

pass as Mediterranean until he was secretly taken off the island by a

British submarine.

Soon after his return home in 1942, Saunders was sent to fight in

the Owen Stanley Range in New Guinea. It was during this time that

he was nominated for promotion to a commissioned rank, a level

never before offered to an Indigenous Australian. After 16 weeks of

officer training in Victoria, Saunders was redeployed in New Guinea

in November 1944 and spent the remainder of the war in command

of a unit of 30 other Australians. After the war Saunders took a break

from the life of a soldier and worked various jobs, until 1950 and the

start of the Korean War, when he returned to the army. He was

captain of the Third Battalion and fought with distinction at Kapyong

and Maryamsam.

After the war Saunders left the army. He eventually moved to

Sydney, where he took up the position of liaison and public relations

officer for the Australian Government’s Office of Aboriginal Affairs.

In 1971, decades after Saunders’s service to Australia, he was awarded

the honor of Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE). In

1985, five years before his death, he was also appointed to the Council

of the Australian War Memorial.

121

REALIGNMENT

in retaliation for the killing of a white dingo trapper. The official num-

ber of Aboriginal people killed is 32, while the unofficial count is at

least twice that number (Wilson and O’Brien 2003). Such retaliatory

expeditions began early in the colonial period (1790) under the direc-

tion of Governor Arthur Phillip “to infuse an universal terror” (Wilson

and O’Brien 2003) in response to Aboriginal attacks on white people or

property. By 1928 police and vigilante acts of retribution had become

so common and disproportionate that the government was increasingly

required to respond with lengthy public investigations. As a result of

this delayed government action, the 1928 Coniston Massacre stands as

the last recorded massacre in Australian history. Though all Europeans

involved in the Coniston killings were cleared of any wrongdoing, the

Northern Territory no longer officially supported “punitive expedi-

tions,” opting instead that white courts settle disputes with Indigenous

people. Unfortunately, in the vast majority of instances, these courts

proved no more just to Aboriginal people.

The Depression

The global financial and political landscape shifted dramatically after

World War I. Power swung to the United States, while the creation

of new nations in Europe dramatically changed the flow of trade and

exchange of currency. One result of this transformation was a short

but deep recession in Australia, in 1920 (Murray in Masson 1993, xv).

Although the economy quickly rallied on the back of the sheep and

steady wheat production, notice had been served: Australia was too

dependent on external demand for its raw materials and international

loans for maintaining its public works. With the stock market crash

of 1929, the country’s export- and loans-driven economy stood no

chance of shielding itself from the events sweeping most of Europe and

the United States. The economic depression of the 1930s saw massive

unemployment, poverty, and deprivation in all Australian cities and

rural communities.

This major world event had its roots in the war. On both the win-

ning and the losing sides, many countries funded the cost of the war by

abandoning gold as the standard by which they valued their currency

and instead simply printed money. Such measures led to inflation that

continued far beyond the conflict, even when the gold standard was

reinstituted. After the war Germany again tried to solve its financial prob-

lems by printing more money, setting off hyperinflation. In addition, the

defeated Axis powers of Austria-Hungary and Germany were unable to

pay the unrealistically high reparations required of them under the Treaty

A BRIEF HISTORY OF AUSTRALIA

122

of Versailles. This failure to pay also contributed to budget problems in

the recipient countries, Britain and France. Another problem for Britain

was a return to the gold standard at too high a rate, which rendered

exports too expensive and overseas demand too low to continue produc-

tion. With a widespread slump in manufacturing, unemployment rose

and remained high in the years leading up to the depression. In contrast,

the U.S. dollar was undervalued, encouraging exports and contributing

to an unsound economic boom and a credit bubble that resulted in the

crash of the stock market in 1929 (Pettinger 2009).

Australia was inextricably caught up in these events because of the

sudden slump in prices for its two main exports, wool and wheat, and

the drying up of loans from London. In the 1920s wool accounted for

40 percent and wheat 15 percent of total exports, with other agricul-

tural products making up the remainder (Murray 1993, xvi). Gold was

no longer being found at prewar rates and other mineral industries

were not yet fully developed. With little self-generated revenue, the

newly elected Labor prime minister, James Scullin, faced a difficult task

in 1929–30 in convincing conservative London financiers, who had lost

significant investments on Wall Street, to fund public works projects in

a former colony where strong union sympathies often clashed with the

interests of investors.

In rural areas small towns built around the business of supplying

farms had no buyers for their goods. Thousands in the country and

city went bankrupt and various large companies went into liquidation.

Unlike that today, the system of unemployment insurance was woe-

fully inadequate to support individuals or keep families together, and

retirement benefits were nonexistent except for government or bank

employees. Australia at the time did not yet have a federal social welfare

system; rather, each state administered its own scheme separately. Only

Queensland provided monetary unemployment insurance, but resi-

dency had to have been established for six months to be eligible. The

other states provided vouchers that allowed the unemployed to collect

small amounts of food (Murray in Masson 1993, xii). In addition, in all

states unemployment aid was not given to young people living at home

if the family had any other form of income. As a result, many people

took to the road in search of work with nothing more than the clothes

on their back and a “swag,” or sleeping bag, for sleeping under the stars

(Murray in Mason 1993, xiii).

Despite our knowledge that life was difficult for many in Australia

in this period, it is a complex matter to give exact figures of the num-

ber of poor and unemployed. Defining who constituted the Australian

123

REALIGNMENT

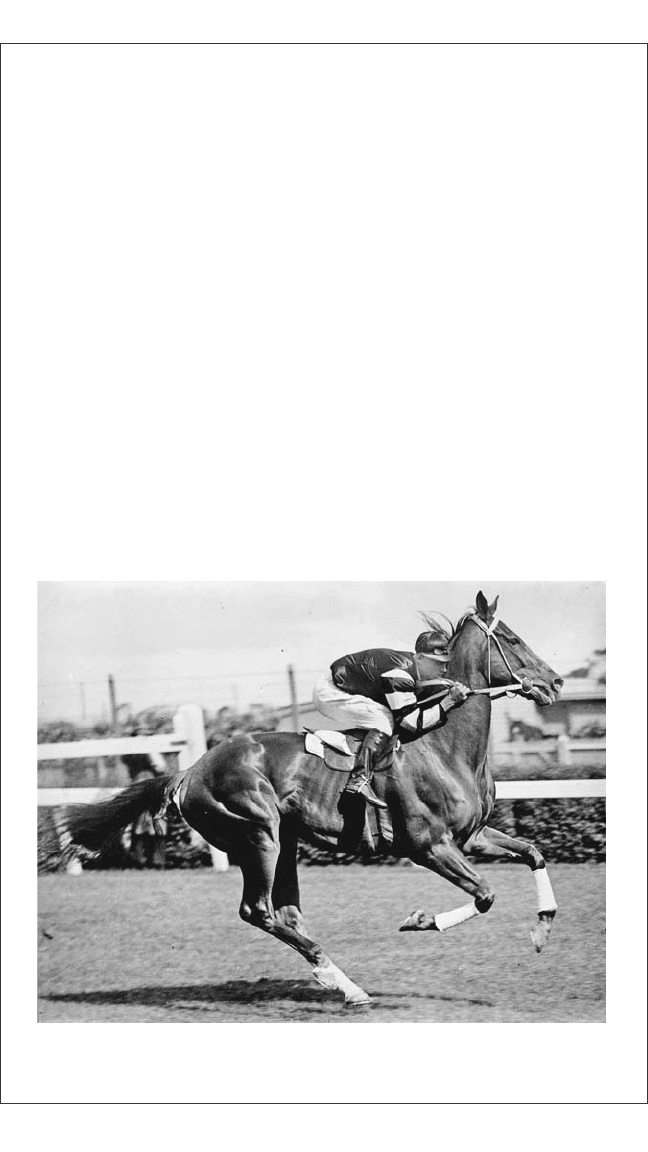

phar Lap

d

uring the height of the depression, Australians turned to vari-

ous forms of entertainment to cushion the difficulties caused

by the worst financial downturn in the modern history of capitalism.

One of the greatest of these diversions was Phar Lap, a racehorse

with an astounding 73 percent win rate, whose name means “light-

ning” in Thai.

Phar Lap’s story begins in New Zealand, where he was born, but

continues in Australia where the trainer Harry Telford took him after

his purchase by an American, David Davis, for the paltry sum of about

US$130. On April 28, 1929, Phar Lap proved his purchase price was

a bargain when he won his first race, the relatively minor Rosehill

Maiden Juvenile Handicap. From there Phar Lap’s reputation grew

along with his prize money. After making his owners just AU£182 in

his first year of racing, Phar Lap went on to earn a total of AU£70,125

over the course of four years, with major wins in the Melbourne Cup,

Victoria Derby, AJC Derby, W. S. Cox Plate (twice) in Australia, and

the Agua Caliente Handicap in Tijuana, Mexico. Along with Phar Lap’s

The jockey Jim Pike riding Phar Lap at Melbourne’s Flemington Racetrack, circa

1930

(Pictures Collection, State Library of Victoria)

(continues)

A BRIEF HISTORY OF AUSTRALIA

124

workforce in the 1930s entailed simply counting the number of trade

union members in each state. Unemployment statistics were collected

by counting the number of union members out of work. This method,

while straightforward, was far too simplistic to capture the true picture

of the economic downturn because it left out various sectors of the

population, including school leavers not yet registered with a union,

part-time workers who would have preferred to be working full time,

most women, and Aboriginal people. Nonetheless, these figures do give

some insight into the startling trends. For example, unemployment

in the 1920s averaged around 7 percent, while by the early 1930s the

figure was around 32 percent. Unemployment was most severe in New

South Wales, where 34 percent of trade union members were out of

work, and South Australia was not far behind, at 32.5 percent. Of all the

states agricultural Queensland was the least affected, with 18.8 percent

unemployment (Murray in Mason 1993, xxvii).

In order to gain the confidence of London investors and get his coun-

try’s economy moving again, Prime Minister Scullin allowed a delegation

from the Bank of England, led by Otto Niemeyer, to enter Australia in

late 1930 to assess the country’s financial situation for themselves. At

numerous victories, the “big, plain looking, cheap-priced underdog”

(Equal Marketing 2006) became a phenomenon during the depression

because both he and his trainer, Telford, were seen by the Australian

public as “battlers.” With their victories over wealthy owners and

horses that had been purchased for 10 times the price, the pair repre-

sented to Australians that hard work and perseverance could prevail

in the end, even during times of depression.

Phar Lap’s reputation only increased when his life was tragically

cut short after his miraculous win at Agua Caliente. Phar Lap died

a painful death in Menlo Park, California, just days after this victory.

At the time Australians suspected that Americans had poisoned their

beloved horse after he defeated their best entrants at Agua Caliente.

Hair analyses in 2006 confirming that Phar Lap had a large amount of

arsenic in his system at the time of death only confirmed what many

Australians had suspected.

Source: Equus Marketing. “The Phar Lap Story” (2006). Available online. URL:

http://www.pharlap.com.au/thestory. Accessed May 21, 2009.

phar Lap (continued)

125

REALIGNMENT

the same time Scullin sailed to the United Kingdom to participate in the

1930 Imperial Conference from which the Statute of Westminster, which

abolished Britain’s power to supersede Australian law, emerged; unfor-

tunately, it proved to be an inopportune time for Scullin to be absent.

Just prior to his five months overseas the government’s deputy leader

and treasurer, Edward Granville (Ted) Theodore, was forced to step

down while under investigation for fraud; simultaneously, Niemeyer’s

presence caused resentment and suspicion from the Left faction within

the Labor Party. As the depression worsened, Australia was without its

leader, deputy leader, and treasurer, while overseas bankers were making

decisions about investments that could make or break the economy.

Scullin returned from the Imperial Conference in January 1931 and

reinstated his deputy, but the factional fighting over this and other

issues had left the party in disarray. Some cabinet members supported

Niemeyer’s assessment that Australia was living beyond its means

and needed to scale spending back significantly. Others demonized

Niemeyer as a representative of callous bankers, intent on sucking the

working classes dry.

The combination of losing a quarter of an Australian generation in

World War I, followed by the Great Depression a mere decade later, left

those who rejected Niemeyer’s assessment significantly disillusioned

with distant powers’ ability to manage world events and, indeed, with

Australia’s involvement in them. One of the key figures representing

those who felt betrayed and resentful of these distant financiers was the

Labor premier of New South Wales, John Thomas (Jack) Lang. Lang

wielded a great deal of influence as the premier of the country’s largest

state by population. He argued for postponement of debt repayments

to overseas bondholders, some of which was war debt to be paid to

Britain. This position was very popular with the general public, espe-

cially traditional Labor voters from the union movement.

On the other side, several cabinet members argued that Australia

had to limit spending. One of those who put forward this case most

vehemently was Joseph Lyons, minister for posts, works, and railways,

who supported Niemeyer’s recommendations wholeheartedly. Lyons

was joined by the majority of state premiers, aside from Lang, whose

“Premiers’ Plan” called for significant cuts in government expenditure

in the areas of greatest financial drain, especially wages and pensions

for government workers.

Scullin was in a bind, torn between supporting the “Langites,” on

one side, and the majority of Australian state premiers in their endorse-

ment of Niemeyer’s recommendations, on the other. In the end, not

A BRIEF HISTORY OF AUSTRALIA

126

wanting to risk the country’s ability to attract future loans, Scullin sided

with the premiers and began cutting back on infrastructure projects

and payments to government employees. For example, the railways

at this time suffered huge financial losses with the fall in business and

so were forced to make large-scale wage and staff cuts; job losses for

nonpermanent government staff were also very high. Other areas of

government spending, including pensions for the elderly, war widows,

and dependents, were reduced, and government bonds lost much of

their value.

In many ways the “Premiers’ Plan” marked the end for Scullin. His

own party was irreparably split between pro-Lang union demands to

increase government spending and postpone overseas debt repayment,

on the one side, and the financially conservative premiers demanding

exactly the opposite, on the other. Eventually, although Scullin had

taken up Niemeyer’s plan, Joseph Lyons and several other conservatives

abandoned the party and, along with the National Party, formed the

United Australia Party (UAP), the predecessor of today’s Liberal Party.

And then, on November 21, 1931, five Labor Party members who had

supported the Langites over the government crossed the floor of the

federal parliament in a vote of no confidence in their own government

and brought the troubled Scullin administration to an end. In the fed-

eral election that followed in December 1931, Joseph Lyons became the

new prime minister as head of the UAP. In coalition with the conserva-

tive Country Party, the UAP held a comfortable majority in parliament.

Lyons went on to lead Australia through the depression; he died in

office in 1939, on the brink of World War II.

Western Australia’s Challenge to National Unity

Although Western Australia federated with Australia in 1901 on the

heels of a successful referendum, very early on many in the state, espe-

cially farmers, began to suspect that they had made the wrong choice

(Molony 2005, 263). From 1906 when the Western Australian legis-

lature first voted in favor of secession, through the 1930s “the ‘yell of

the secessionist’ was loud” in that state (Molony 2005, 263). The two

issues that contributed most directly to the dissatisfaction felt by many

Western Australians were the distance from the “business and power

interests of its eastern cousins” and tariffs that made “it hard for WA

to sell its primary exports on a world market where it had no protec-

tion” (Constitutional Centre of Western Australia 2008). Organized

protest began anew in 1926 with the formation of the Secession League

and continued with the more successful Dominion League of Western

127

REALIGNMENT

Australia after 1930. The secessionists were opposed by the state’s few

industrialists in the Federal League, formed in 1931, and by those who

lived in the gold districts. Both of these constituents benefited from

their ties to the commercial centers in the country’s east and saw little

benefit in aligning themselves with farmers and graziers.

Finally, when a scapegoat was being sought for the economic diffi-

culties of the depression in 1933, the conservative Western Australian

government, which had supported the secessionists, called for a refer-

endum on the issue. The issue passed with 68 percent of the 237,198

votes cast. With more than 91 percent of eligible voters participating,

only gold miners rejected the notion en masse (Constitutional Centre

of WA 2008). Interestingly, at the same election the conservative and

prosecessionist government of James Mitchell was swept from power

and replaced by the Labor Party under Philip Collier, which had

opposed secession (National Council for the Centenary of Federation

2008).

Despite the overwhelming vote in favor, Western Australians’ bid for

independence did not eventuate. A delegation of prosecessionists was

dispatched from Western Australia in 1934 to present the case for “ ‘res-

toration’ of the State to ‘its former status as a separate and distinct self-

governing colony in the British Empire’ ” (Constitutional Centre of WA

2008). They spent two years in London trying to gain access to a full

parliamentary review of their argument, but a joint committee from the

Houses of Commons and Lords rejected the “petition on the grounds

that the British Parliament could not act without the Australian Federal

Parliament’s approval” (Constitutional Centre of WA 2008). After this

failure the secessionist movement largely disintegrated; however, even

today small numbers of Western Australians continue to chafe at the

financial and legal bounds of remaining in the Commonwealth.

Australian Landscape

In the years between 1920 and 1946 Australians compounded the

effects of European migration on the continent’s fragile environment

with larger and larger infrastructure projects, leading to further degra-

dation of indigenous flora and fauna. Certainly dozens of smaller mar-

supials were already under threat with the introduction of the domestic

cat at an unknown time prior to the First Fleet in 1788, probably from

Dutch ships; the wild rabbit in 1839; and the fox in 1845; sheep and

cattle also successfully competed for food and water in much of the

continent, further damaging indigenous flora and fauna. In this later

A BRIEF HISTORY OF AUSTRALIA

128

period, however, “the destruction of habitat accelerated spectacularly

as the twentieth century’s technological revolution got under way”

(Andrewartha and Birch 1986, 182).

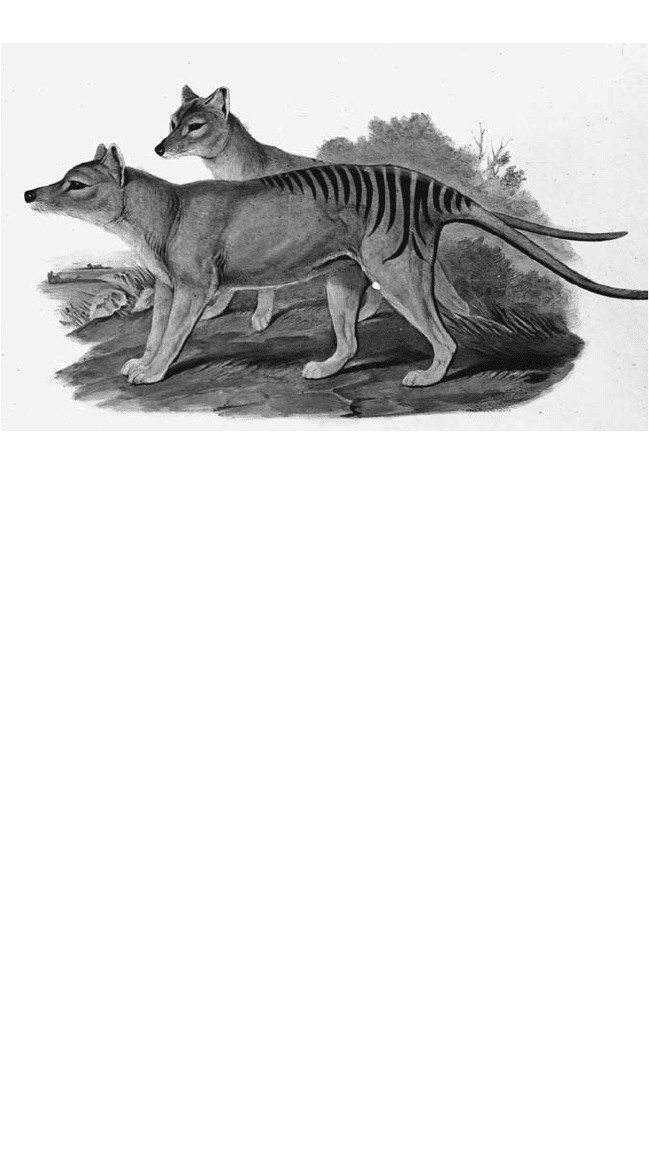

A key symbol of this destruction was the death in 1936 of the last

Tasmanian tiger, or thylacine, the largest carnivorous marsupial to

have survived into the 20th century. Starting in 1830 the various colo-

nial and state governments that administered Tasmania (Van Diemen’s

Land) put bounties on the tiger, mainly because of the threat it posed to

household animals and stock. In 1909 after 2,184 bounties were paid,

the practice was finally ended and the tiger sought primarily by zoos

wanting an example of the animal for their collections; the last one was

captured for this purpose in 1933. The last known survivor died in cap-

tivity at the Hobart zoo in September 1936, chained outside and dying

of the cold (Tasmania Parks and Wildlife Service 2008). Occasionally

people in both Tasmania and on the mainland, where they are believed

to have become extinct about 7,000 years ago, claim to have seen a

thylacine, but no sighting has been verified since the 1930s.

A second important ecological development occurred in the mid-

1930s with the introduction of a prolific nonnative species. In 1935 the

Australian Bureau of Sugar Experimental Stations imported 100 cane

toads, Bufo marinus, from Hawaii in an attempt to control several spe-

cies of beetle that were damaging Queensland’s lucrative sugar industry.

Thylacines were also known as Tasmanian marsupial wolves and Tasmanian tigers before

their extinction in the 1930s.

(Pictures Collection, State Library of Victoria)

129

REALIGNMENT

The first release of 100 toads near Cairns, Queensland, was followed a

month later by release of 3,000 more onto sugar plantations throughout

northern Queensland, despite the lack of evidence that they did any-

thing to limit the beetle population. It has since been proven that the

toads have no effect on the beetle problem.

Even at the time several environmentalists, such as the museum cura-

tor Roy Kinghorn and the government entomologist W. W. Froggatt,

protested the introduction, but to no avail (Australian Museum Online

2003). Today their warnings seem prescient. The toad population, in

the millions and spreading around Australia at a rate of about a mile

per year, endangers indigenous wildlife in three ways: competition for

food, eating small animals, and poison glands, which cause everything

that eats the toad itself to die very quickly of heart failure (National

Heritage Trust 2004). So far, efforts to control the toad have met with

almost no success, and it remains one of the most dangerous of the

continent’s invasive pests.

In addition to this kind of experimentation, the first half of the 20th

century saw the completion of many large infrastructural projects that

further symbolized European Australians’ desire to control and tame

their fragile environment. The Hume Dam was begun in November

1919 in an effort to control flooding from the Murray River and to har-

ness water for irrigation and domestic and industrial use. In 1936 the

completed dam was the largest in the Southern Hemisphere and second

largest in the world at the time, at 131 feet (40 meters) high and 5,300

feet (1,615 meters) long; the resulting reservoir held 407 billion gallons

(15,420 Gl) of water. Since that time, however, changes to the dam

and drought have affected the water levels and led to a perception that

the lake is “dry and empty,” despite the nearly four square miles (10

sq. km) of water available for boating, water skiing, fishing, and other

recreational activities (Border Mail 2008).

The dam and resulting lake have also been blamed for significant

environmental damage along the course of the Murray River. The river’s

natural cycle is to run very high and cold in winter and then peter out

to almost nothing in the hot, dry summer months. Indigenous fish and

plant life were adapted to that cycle, and with its disruption such native

species as the Murray cod and mangrove swamps have come under

threat. The multistate management of the entire Murray basin, which

is located in New South Wales, Victoria, and South Australia, has also

led to considerable disagreement over how best to deal with the envi-

ronment, as well as water disputes, and the threat to the basin and its

ecology continues to this day.