Banner A. The Calculus Lifesaver: All the Tools You Need to Excel at Calculus

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

426 • Techniques of Integration, Part Two

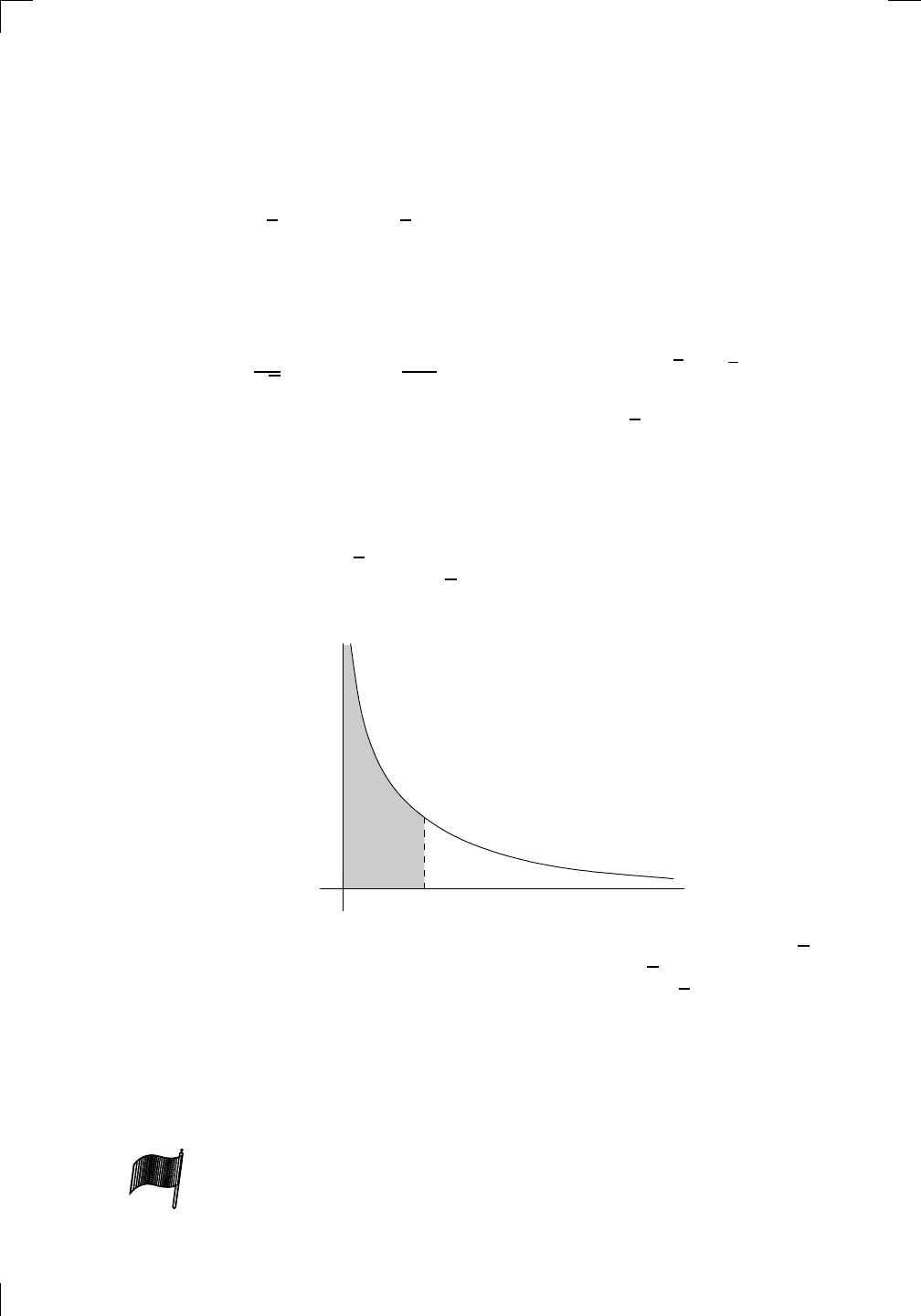

Remember, this only applies when x > 0. We’ll revisit this example in Sec-

tion 19.3.6 to see how to take care of the case when x ≤ 0.

19.3.4 Completing the square and trig substitutions

Now, one other important point before we summarize the situation. From

time to time, you might want to solve an integral involving an odd power

of

√

±x

2

+ ax + b. That is, you now have a linear term ax to complicate

matters. The technique is simple: complete the square first and substitute

to get it into one of the three types that we’ve investigated. For example, to

evaluate

PSfrag

replacements

(

a, b)

[

a, b]

(

a, b]

[

a, b)

(

a, ∞)

[

a, ∞)

(

−∞, b)

(

−∞, b]

(

−∞, ∞)

{

x : a < x < b}

{

x : a ≤ x ≤ b}

{

x : a < x ≤ b}

{

x : a ≤ x < b}

{

x : x ≥ a}

{

x : x > a}

{

x : x ≤ b}

{

x : x < b}

R

a

b

shado

w

0

1

4

−

2

3

−

3

g(

x) = x

2

f(

x) = x

3

g(

x) = x

2

f(

x) = x

3

mirror

(y = x)

f

−

1

(x) =

3

√

x

y = h

(x)

y = h

−

1

(x)

y =

(x − 1)

2

−

1

x

Same

height

−

x

Same

length,

opp

osite signs

y = −

2x

−

2

1

y =

1

2

x − 1

2

−

1

y =

2

x

y =

10

x

y =

2

−x

y =

log

2

(x)

4

3

units

mirror

(x-axis)

y = |

x|

y = |

log

2

(x)|

θ radians

θ units

30

◦

=

π

6

45

◦

=

π

4

60

◦

=

π

3

120

◦

=

2

π

3

135

◦

=

3

π

4

150

◦

=

5

π

6

90

◦

=

π

2

180

◦

= π

210

◦

=

7

π

6

225

◦

=

5

π

4

240

◦

=

4

π

3

270

◦

=

3

π

2

300

◦

=

5

π

3

315

◦

=

7

π

4

330

◦

=

11

π

6

0

◦

=

0 radians

θ

hypotenuse

opp

osite

adjacen

t

0

(≡ 2π)

π

2

π

3

π

2

I

I

I

I

II

IV

θ

(

x, y)

x

y

r

7

π

6

reference

angle

reference

angle =

π

6

sin

+

sin −

cos

+

cos −

tan

+

tan −

A

S

T

C

7

π

4

9

π

13

5

π

6

(this

angle is

5π

6

clo

ckwise)

1

2

1

2

3

4

5

6

0

−

1

−

2

−

3

−

4

−

5

−

6

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

2π

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

3

π

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

3

π

2

π

π

2

y =

sin(x)

1

0

−

1

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

2π

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

2

π

3

π

2

π

π

2

y =

sin(x)

y =

cos(x)

−

π

2

π

2

y =

tan(x), −

π

2

<

x <

π

2

0

−

π

2

π

2

y =

tan(x)

−

2π

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

π

2

3

π

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

3

π

2

π

y =

sec(x)

y =

csc(x)

y =

cot(x)

y = f(

x)

−

1

1

2

y = g(

x)

3

y = h

(x)

4

5

−

2

f(

x) =

1

x

g(

x) =

1

x

2

etc.

0

1

π

1

2

π

1

3

π

1

4

π

1

5

π

1

6

π

1

7

π

g(

x) = sin

1

x

1

0

−

1

L

10

100

200

y =

π

2

y = −

π

2

y =

tan

−1

(x)

π

2

π

y =

sin(

x)

x

,

x > 3

0

1

−

1

a

L

f(

x) = x sin (1/x)

(0 <

x < 0.3)

h

(x) = x

g(

x) = −x

a

L

lim

x

→a

+

f(x) = L

lim

x

→a

+

f(x) = ∞

lim

x

→a

+

f(x) = −∞

lim

x

→a

+

f(x) DNE

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) = L

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) = ∞

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) = −∞

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) DNE

M

}

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) = M

lim

x

→a

f(x) = L

lim

x

→a

f(x) DNE

lim

x

→∞

f(x) = L

lim

x

→∞

f(x) = ∞

lim

x

→∞

f(x) = −∞

lim

x

→∞

f(x) DNE

lim

x

→−∞

f(x) = L

lim

x

→−∞

f(x) = ∞

lim

x

→−∞

f(x) = −∞

lim

x

→−∞

f(x) DNE

lim

x →a

+

f(

x) = ∞

lim

x →a

+

f(

x) = −∞

lim

x →a

−

f(

x) = ∞

lim

x →a

−

f(

x) = −∞

lim

x →a

f(

x) = ∞

lim

x →a

f(

x) = −∞

lim

x →a

f(

x) DNE

y = f (

x)

a

y =

|

x|

x

1

−

1

y =

|

x + 2|

x +

2

1

−

1

−

2

1

2

3

4

a

a

b

y = x sin

1

x

y = x

y = −

x

a

b

c

d

C

a

b

c

d

−

1

0

1

2

3

time

y

t

u

(

t, f(t))

(

u, f(u))

time

y

t

u

y

x

(

x, f(x))

y = |

x|

(

z, f(z))

z

y = f(

x)

a

tangen

t at x = a

b

tangen

t at x = b

c

tangen

t at x = c

y = x

2

tangen

t

at x = −

1

u

v

uv

u +

∆u

v +

∆v

(

u + ∆u)(v + ∆v)

∆

u

∆

v

u

∆v

v∆

u

∆

u∆v

y = f(

x)

1

2

−

2

y = |

x

2

− 4|

y = x

2

− 4

y = −

2x + 5

y = g(

x)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

−

1

−

2

−

3

−

4

−

5

−

6

y = f (

x)

3

−

3

3

−

3

0

−

1

2

easy

hard

flat

y = f

0

(

x)

3

−

3

0

−

1

2

1

−

1

y =

sin(x)

y = x

x

A

B

O

1

C

D

sin(

x)

tan(

x)

y =

sin(

x)

x

π

2

π

1

−

1

x =

0

a =

0

x

> 0

a

> 0

x

< 0

a

< 0

rest

position

+

−

y = x

2

sin

1

x

N

A

B

H

a

b

c

O

H

A

B

C

D

h

r

R

θ

1000

2000

α

β

p

h

y = g(

x) = log

b

(x)

y = f(

x) = b

x

y = e

x

5

10

1

2

3

4

0

−

1

−

2

−

3

−

4

y =

ln(x)

y =

cosh(x)

y =

sinh(x)

y =

tanh(x)

y =

sech(x)

y =

csch(x)

y =

coth(x)

1

−

1

y = f(

x)

original

function

in

verse function

slop

e = 0 at (x, y)

slop

e is infinite at (y, x)

−

108

2

5

1

2

1

2

3

4

5

6

0

−

1

−

2

−

3

−

4

−

5

−

6

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

2π

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

3

π

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

3

π

2

π

π

2

y =

sin(x)

1

0

−

1

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

2π

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

2

π

3

π

2

π

π

2

y =

sin(x)

y =

sin(x), −

π

2

≤ x ≤

π

2

−

2

−

1

0

2

π

2

−

π

2

y =

sin

−1

(x)

y =

cos(x)

π

π

2

y =

cos

−1

(x)

−

π

2

1

x

α

β

y =

tan(x)

y =

tan(x)

1

y =

tan

−1

(x)

y =

sec(x)

y =

sec

−1

(x)

y =

csc

−1

(x)

y =

cot

−1

(x)

1

y =

cosh

−1

(x)

y =

sinh

−1

(x)

y =

tanh

−1

(x)

y =

sech

−1

(x)

y =

csch

−1

(x)

y =

coth

−1

(x)

(0

, 3)

(2

, −1)

(5

, 2)

(7

, 0)

(

−1, 44)

(0

, 1)

(1

, −12)

(2

, 305)

y =

1

2

(2

, 3)

y = f(

x)

y = g(

x)

a

b

c

a

b

c

s

c

0

c

1

(

a, f(a))

(

b, f(b))

1

2

1

2

3

4

5

6

0

−

1

−

2

−

3

−

4

−

5

−

6

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

2π

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

3

π

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

3

π

2

π

π

2

y =

sin(x)

1

0

−

1

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

2π

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

2

π

3

π

2

π

π

2

c

OR

Lo

cal maximum

Lo

cal minimum

Horizon

tal point of inflection

1

e

y = f

0

(

x)

y = f (

x) = x ln(x)

−

1

e

?

y = f(

x) = x

3

y = g(

x) = x

4

x

f(

x)

−

3

−

2

−

1

0

1

2

1

2

3

4

+

−

?

1

5

6

3

f

0

(

x)

2 −

1

2

√

6

2

+

1

2

√

6

f

00

(

x)

7

8

g

00

(

x)

f

00

(

x)

0

y =

(

x − 3)(x − 1)

2

x

3

(

x + 2)

y = x ln

(x)

1

e

−

1

e

5

−

108

2

α

β

2 −

1

2

√

6

2

+

1

2

√

6

y = x

2

(

x − 5)

3

−

e

−

1/2

√

3

e

−

1/2

√

3

−

e

−3/2

e

−

3/2

−

1

√

3

1

√

3

−

1

1

y = xe

−

3x

2

/2

y =

x

3

− 6

x

2

+ 13x − 8

x

28

2

600

500

400

300

200

100

0

−

100

−

200

−

300

−

400

−

500

−

600

0

10

−

10

5

−

5

20

−

20

15

−

15

0

4

5

6

x

P

0

(

x)

+

−

−

existing

fence

new

fence

enclosure

A

h

b

H

99

100

101

h

dA/dh

r

h

1

2

7

shallo

w

deep

LAND

SEA

N

y

z

s

t

3

11

9

L

(11)

√

11

y = L

(x)

y = f (

x)

11

y = L

(x)

y = f(

x)

F

P

a

a +

∆x

f(

a + ∆x)

L

(a + ∆x)

f(

a)

error

d

f

∆

x

a

b

y = f(

x)

true

zero

starting

approximation

b

etter approximation

v

t

3

5

50

40

60

4

20

30

25

t

1

t

2

t

3

t

4

t

n

−2

t

n

−1

t

0

= a

t

n

= b

v

1

v

2

v

3

v

4

v

n

−1

v

n

−

30

6

30

|

v|

a

b

p

q

c

v(

c)

v(

c

1

)

v(

c

2

)

v(

c

3

)

v(

c

4

)

v(

c

5

)

v(

c

6

)

t

1

t

2

t

3

t

4

t

5

c

1

c

2

c

3

c

4

c

5

c

6

t

0

=

a

t

6

=

b

t

16

=

b

t

10

=

b

a

b

x

y

y = f(

x)

1

2

y = x

5

0

−

2

y =

1

a

b

y =

sin(x)

π

−

π

0

−

1

−

2

0

2

4

y = x

2

0

1

2

3

4

2

n

4

n

6

n

2(

n−2)

n

2(

n−1)

n

2

n

n

=

2

width

of each interval =

2

n

−

2

1

3

0

I

I

I

I

II

IV

4

y

dx

y = −

x

2

− 2x + 3

3

−

5

y = |−

x

2

− 2x + 3|

I

I

I

I

Ia

5

3

0

1

2

a

b

y = f (

x)

y = g(

x)

y = x

2

a

b

5

3

0

1

2

y =

√

x

2

√

2

2

2

dy

x

2

a

b

y = f(

x)

y = g(

x)

M

m

1

2

−

1

−

2

0

y = e

−

x

2

1

2

e

−1/4

f

av

y = f

av

c

A

M

0

1

2

a

b

x

t

y = f (t)

F (x )

y = f (t)

F (x + h)

x + h

F (x + h) − F (x)

f(x)

1

2

y = sin(x)

π

−π

−1

−2

y =

1

x

y = x

2

1

2

1

−1

y = ln|x|

θ

a

x

a

x

p

a

2

− x

2

3

x

p

9 − x

2

p

x

2

+ a

2

x

a

p

x

2

+ 15

x

√

15

x

p

x

2

− a

2

a

x

p

x

2

− 4

2

Z

(x

2

− 4x + 19)

−5/2

dx,

first complete the square (see Section 1.6 of Chapter 1 for a reminder of how

to do this):

x

2

− 4x + 19 = (x

2

− 4x + 4) − 4 + 19 = (x − 2)

2

+ 15.

So the integral we want is actually

Z

((x − 2)

2

+ 15)

−5/2

dx.

Now let t = x − 2, so dt = dx, and in t-land the integral becomes

Z

(t

2

+ 15)

−5/2

dt,

which we have already done earlier in Section 19.3.2! The answer was (replac-

ing the old x by t)

1

225

t

√

t

2

+ 15

−

t

3

3(t

2

+ 15)

3/2

+ C,

so replacing t now by x − 2, we see that

Z

(x

2

− 4x + 19)

−5/2

dx =

1

225

x − 2

√

x

2

− 4x + 19

−

(x − 2)

3

3(x

2

− 4x + 19)

3/2

+ C.

The moral of the story, both here and when using partial fractions, is that

a quadratic with a linear term can be made into a quadratic without one by

completing the square and substituting.

19.3.5 Summary of trig substitutions

To summarize the three main types we’ve looked at, here’s a table that shows

the appropriate substitutions and triangles for each type:

PSfrag

replacements

(

a, b)

[

a, b]

(

a, b]

[

a, b)

(

a, ∞)

[

a, ∞)

(

−∞, b)

(

−∞, b]

(

−∞, ∞)

{

x : a < x < b}

{

x : a ≤ x ≤ b}

{

x : a < x ≤ b}

{

x : a ≤ x < b}

{

x : x ≥ a}

{

x : x > a}

{

x : x ≤ b}

{

x : x < b}

R

a

b

shado

w

0

1

4

−

2

3

−

3

g(

x) = x

2

f(

x) = x

3

g(

x) = x

2

f(

x) = x

3

mirror

(y = x)

f

−

1

(x) =

3

√

x

y = h

(x)

y = h

−

1

(x)

y =

(x − 1)

2

−

1

x

Same

height

−

x

Same

length,

opp

osite signs

y = −

2x

−

2

1

y =

1

2

x − 1

2

−

1

y =

2

x

y =

10

x

y =

2

−x

y =

log

2

(x)

4

3

units

mirror

(x-axis)

y = |

x|

y = |

log

2

(x)|

θ radians

θ units

30

◦

=

π

6

45

◦

=

π

4

60

◦

=

π

3

120

◦

=

2

π

3

135

◦

=

3

π

4

150

◦

=

5

π

6

90

◦

=

π

2

180

◦

= π

210

◦

=

7

π

6

225

◦

=

5

π

4

240

◦

=

4

π

3

270

◦

=

3

π

2

300

◦

=

5

π

3

315

◦

=

7

π

4

330

◦

=

11

π

6

0

◦

=

0 radians

θ

hypotenuse

opp

osite

adjacen

t

0

(≡ 2π)

π

2

π

3

π

2

I

I

I

I

II

IV

θ

(

x, y)

x

y

r

7

π

6

reference

angle

reference

angle =

π

6

sin

+

sin −

cos

+

cos −

tan

+

tan −

A

S

T

C

7

π

4

9

π

13

5

π

6

(this

angle is

5π

6

clo

ckwise)

1

2

1

2

3

4

5

6

0

−

1

−

2

−

3

−

4

−

5

−

6

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

2π

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

3

π

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

3

π

2

π

π

2

y =

sin(x)

1

0

−

1

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

2π

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

2

π

3

π

2

π

π

2

y =

sin(x)

y =

cos(x)

−

π

2

π

2

y =

tan(x), −

π

2

<

x <

π

2

0

−

π

2

π

2

y =

tan(x)

−

2π

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

π

2

3

π

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

3

π

2

π

y =

sec(x)

y =

csc(x)

y =

cot(x)

y = f (

x)

−

1

1

2

y = g(

x)

3

y = h

(x)

4

5

−

2

f(

x) =

1

x

g(

x) =

1

x

2

etc.

0

1

π

1

2

π

1

3

π

1

4

π

1

5

π

1

6

π

1

7

π

g(

x) = sin

1

x

1

0

−

1

L

10

100

200

y =

π

2

y = −

π

2

y =

tan

−1

(x)

π

2

π

y =

sin(

x)

x

,

x > 3

0

1

−

1

a

L

f(

x) = x sin (1/x)

(0 <

x < 0.3)

h

(x) = x

g(

x) = −x

a

L

lim

x

→a

+

f(x) = L

lim

x

→a

+

f(x) = ∞

lim

x

→a

+

f(x) = −∞

lim

x

→a

+

f(x) DNE

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) = L

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) = ∞

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) = −∞

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) DNE

M

}

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) = M

lim

x

→a

f(x) = L

lim

x

→a

f(x) DNE

lim

x

→∞

f(x) = L

lim

x

→∞

f(x) = ∞

lim

x

→∞

f(x) = −∞

lim

x

→∞

f(x) DNE

lim

x

→−∞

f(x) = L

lim

x

→−∞

f(x) = ∞

lim

x

→−∞

f(x) = −∞

lim

x

→−∞

f(x) DNE

lim

x →a

+

f(

x) = ∞

lim

x →a

+

f(

x) = −∞

lim

x →a

−

f(

x) = ∞

lim

x →a

−

f(

x) = −∞

lim

x →a

f(

x) = ∞

lim

x →a

f(

x) = −∞

lim

x →a

f(

x) DNE

y = f (

x)

a

y =

|

x|

x

1

−

1

y =

|

x + 2|

x +

2

1

−

1

−

2

1

2

3

4

a

a

b

y = x sin

1

x

y = x

y = −

x

a

b

c

d

C

a

b

c

d

−

1

0

1

2

3

time

y

t

u

(

t, f(t))

(

u, f(u))

time

y

t

u

y

x

(

x, f(x))

y = |

x|

(

z, f(z))

z

y = f (

x)

a

tangen

t at x = a

b

tangen

t at x = b

c

tangen

t at x = c

y = x

2

tangen

t

at x = −

1

u

v

uv

u +

∆u

v +

∆v

(

u + ∆u)(v + ∆v)

∆

u

∆

v

u

∆v

v∆

u

∆

u∆v

y = f (

x)

1

2

−

2

y = |

x

2

− 4|

y = x

2

− 4

y = −

2x + 5

y = g(

x)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

−

1

−

2

−

3

−

4

−

5

−

6

y = f (

x)

3

−

3

3

−

3

0

−

1

2

easy

hard

flat

y = f

0

(

x)

3

−

3

0

−

1

2

1

−

1

y =

sin(x)

y = x

x

A

B

O

1

C

D

sin(

x)

tan(

x)

y =

sin

(x)

x

π

2

π

1

−

1

x =

0

a =

0

x

> 0

a

> 0

x

< 0

a

< 0

rest

position

+

−

y = x

2

sin

1

x

N

A

B

H

a

b

c

O

H

A

B

C

D

h

r

R

θ

1000

2000

α

β

p

h

y = g(

x) = log

b

(x)

y = f (

x) = b

x

y = e

x

5

10

1

2

3

4

0

−

1

−

2

−

3

−

4

y =

ln(x)

y =

cosh(x)

y =

sinh(x)

y =

tanh(x)

y =

sech(x)

y =

csch(x)

y =

coth(x)

1

−

1

y = f (

x)

original

function

in

verse function

slop

e = 0 at (x, y)

slop

e is infinite at (y, x)

−

108

2

5

1

2

1

2

3

4

5

6

0

−

1

−

2

−

3

−

4

−

5

−

6

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

2π

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

3

π

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

3

π

2

π

π

2

y =

sin(x)

1

0

−

1

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

2π

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

2

π

3

π

2

π

π

2

y =

sin(x)

y =

sin(x), −

π

2

≤ x ≤

π

2

−

2

−

1

0

2

π

2

−

π

2

y =

sin

−1

(x)

y =

cos(x)

π

π

2

y =

cos

−1

(x)

−

π

2

1

x

α

β

y =

tan(x)

y =

tan(x)

1

y =

tan

−1

(x)

y =

sec(x)

y =

sec

−1

(x)

y =

csc

−1

(x)

y =

cot

−1

(x)

1

y =

cosh

−1

(x)

y =

sinh

−1

(x)

y =

tanh

−1

(x)

y =

sech

−1

(x)

y =

csch

−1

(x)

y =

coth

−1

(x)

(0

, 3)

(2

, −1)

(5

, 2)

(7

, 0)

(

−1, 44)

(0

, 1)

(1

, −12)

(2

, 305)

y =

1

2

(2

, 3)

y = f (

x)

y = g(

x)

a

b

c

a

b

c

s

c

0

c

1

(

a, f(a))

(

b, f(b))

1

2

1

2

3

4

5

6

0

−

1

−

2

−

3

−

4

−

5

−

6

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

2π

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

3

π

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

3

π

2

π

π

2

y =

sin(x)

1

0

−

1

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

2π

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

2

π

3

π

2

π

π

2

c

OR

Lo

cal maximum

Lo

cal minimum

Horizon

tal point of inflection

1

e

y = f

0

(

x)

y = f(

x) = x ln(x)

−

1

e

?

y = f(

x) = x

3

y = g(

x) = x

4

x

f(

x)

−

3

−

2

−

1

0

1

2

1

2

3

4

+

−

?

1

5

6

3

f

0

(

x)

2 −

1

2

√

6

2

+

1

2

√

6

f

00

(

x)

7

8

g

00

(

x)

f

00

(

x)

0

y =

(

x − 3)(x − 1)

2

x

3

(

x + 2)

y = x ln

(x)

1

e

−

1

e

5

−

108

2

α

β

2 −

1

2

√

6

2

+

1

2

√

6

y = x

2

(

x − 5)

3

−

e

−

1/2

√

3

e

−

1/2

√

3

−

e

−3/2

e

−

3/2

−

1

√

3

1

√

3

−

1

1

y = xe

−

3x

2

/2

y =

x

3

− 6

x

2

+ 13x − 8

x

28

2

600

500

400

300

200

100

0

−

100

−

200

−

300

−

400

−

500

−

600

0

10

−

10

5

−

5

20

−

20

15

−

15

0

4

5

6

x

P

0

(

x)

+

−

−

existing

fence

new

fence

enclosure

A

h

b

H

99

100

101

h

dA/dh

r

h

1

2

7

shallo

w

deep

LAND

SEA

N

y

z

s

t

3

11

9

L

(11)

√

11

y = L

(x)

y = f (

x)

11

y = L

(x)

y = f (

x)

F

P

a

a +

∆x

f(

a + ∆x)

L

(a + ∆x)

f(

a)

error

d

f

∆

x

a

b

y = f (

x)

true

zero

starting

approximation

b

etter approximation

v

t

3

5

50

40

60

4

20

30

25

t

1

t

2

t

3

t

4

t

n

−2

t

n

−1

t

0

= a

t

n

= b

v

1

v

2

v

3

v

4

v

n

−1

v

n

−

30

6

30

|

v|

a

b

p

q

c

v(

c)

v(

c

1

)

v(

c

2

)

v(

c

3

)

v(

c

4

)

v(

c

5

)

v(

c

6

)

t

1

t

2

t

3

t

4

t

5

c

1

c

2

c

3

c

4

c

5

c

6

t

0

=

a

t

6

=

b

t

16

=

b

t

10

=

b

a

b

x

y

y = f (

x)

1

2

y = x

5

0

−

2

y =

1

a

b

y =

sin(x)

π

−

π

0

−

1

−

2

0

2

4

y = x

2

0

1

2

3

4

2

n

4

n

6

n

2(

n−2)

n

2(

n−1)

n

2

n

n

=

2

width

of each interval =

2

n

−

2

1

3

0

I

I

I

I

II

IV

4

y

dx

y = −

x

2

− 2x + 3

3

−

5

y = |−

x

2

− 2x + 3|

I

I

I

IIa

5

3

0

1

2

a

b

y = f (x)

y = g(x)

y = x

2

a

b

5

3

0

1

2

y =

√

x

2

√

2

2

2

dy

x

2

a

b

y = f (x)

y = g(x)

M

m

1

2

−1

−2

0

y = e

−x

2

1

2

e

−1/4

f

av

y = f

av

c

A

M

0

1

2

a

b

x

t

y = f(t)

F (x )

y = f(t)

F (x + h )

x + h

F (x + h) − F (x)

f(x)

1

2

y = sin(x)

π

−π

−1

−2

y =

1

x

y = x

2

1

2

1

−1

y = ln|x|

θ

a

x

a

x

p

a

2

− x

2

3

x

p

9 − x

2

p

x

2

+ a

2

x

a

p

x

2

+ 15

x

√

15

x

p

x

2

− a

2

a

x

p

x

2

− 4

2

Section 19.3.6: Technicalities of square roots and trig substitutions • 427

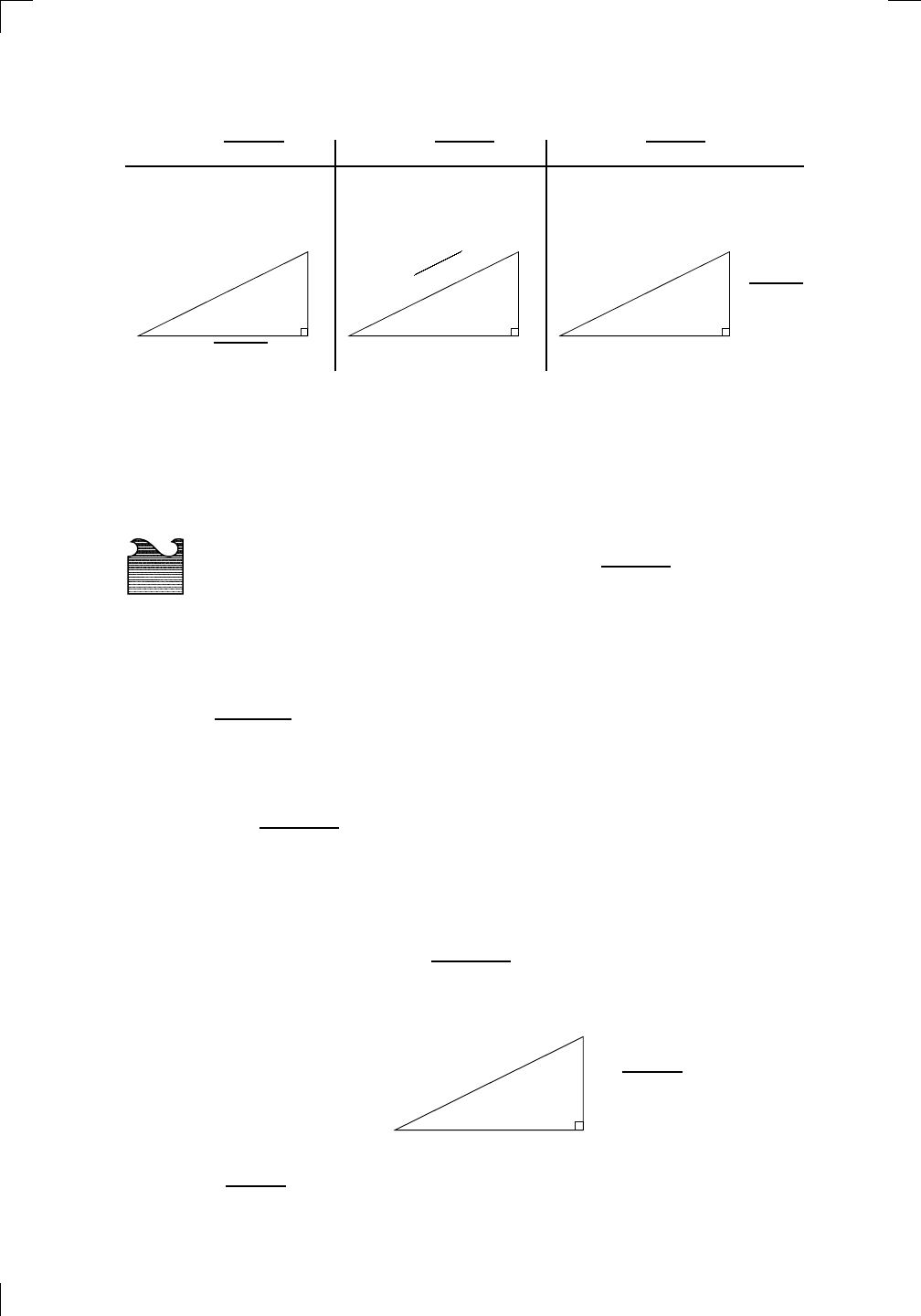

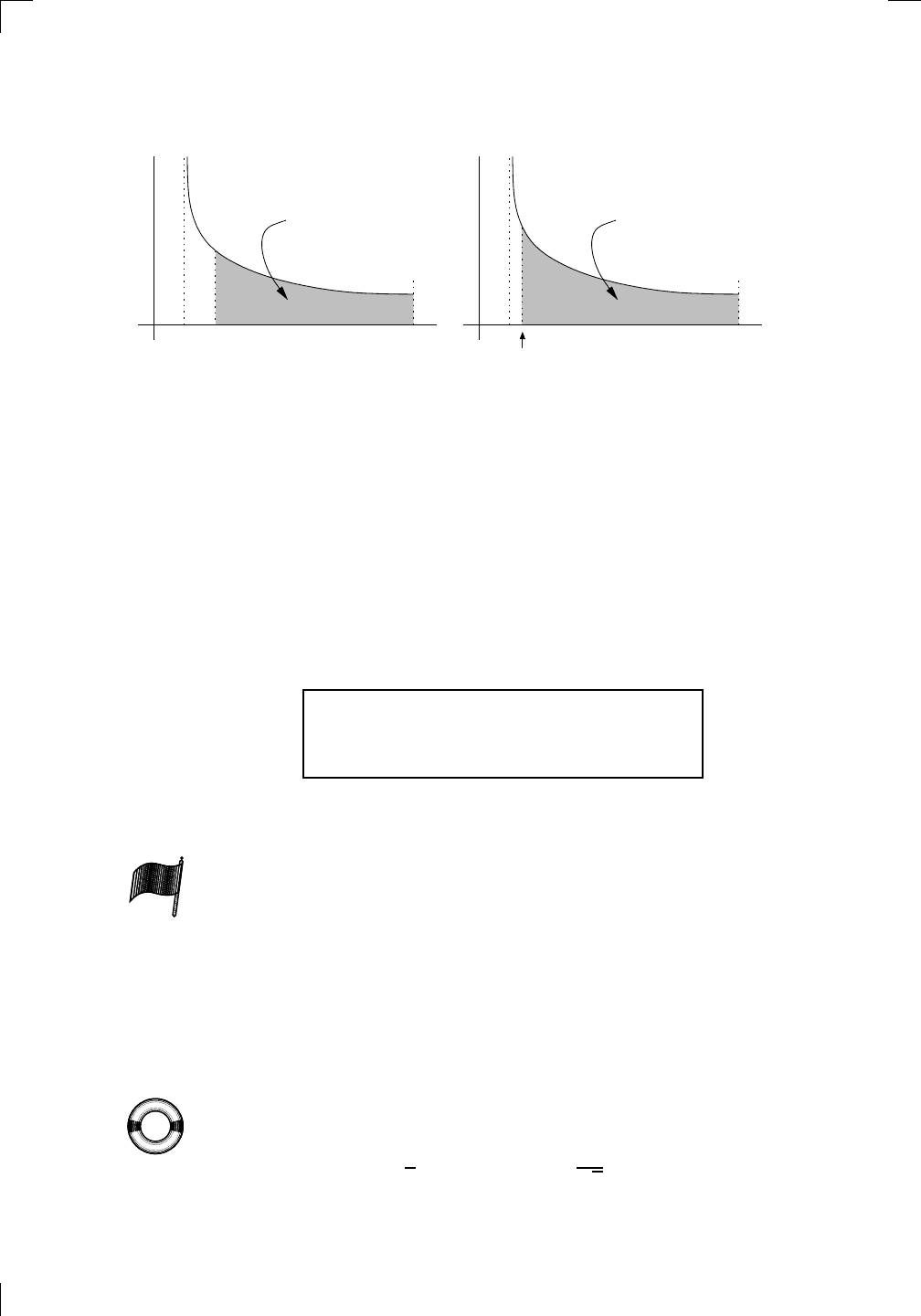

Type 1:

p

a

2

− x

2

Type 2:

p

x

2

+ a

2

Type 3:

p

x

2

− a

2

Set x = a sin(θ) Set x = a tan(θ) Set x = a sec(θ)

dx = a cos(θ) dθ dx = a sec

2

(θ) dθ dx = a sec(θ) tan(θ) dθ

a

2

− x

2

= a

2

cos

2

(θ) x

2

+ a

2

= a

2

sec

2

(θ) x

2

− a

2

= a

2

tan

2

(θ)

PSfrag

replacements

(

a, b)

[

a, b]

(

a, b]

[

a, b)

(

a, ∞)

[

a, ∞)

(

−∞, b)

(

−∞, b]

(

−∞, ∞)

{

x : a < x < b}

{

x : a ≤ x ≤ b}

{

x : a < x ≤ b}

{

x : a ≤ x < b}

{

x : x ≥ a}

{

x : x > a}

{

x : x ≤ b}

{

x : x < b}

R

a

b

shado

w

0

1

4

−

2

3

−

3

g(

x) = x

2

f(

x) = x

3

g(

x) = x

2

f(

x) = x

3

mirror

(y = x)

f

−

1

(x) =

3

√

x

y = h

(x)

y = h

−

1

(x)

y =

(x − 1)

2

−

1

x

Same

height

−

x

Same

length,

opp

osite signs

y = −

2x

−

2

1

y =

1

2

x − 1

2

−

1

y =

2

x

y =

10

x

y =

2

−x

y =

log

2

(x)

4

3

units

mirror

(x-axis)

y = |

x|

y = |

log

2

(x)|

θ radians

θ units

30

◦

=

π

6

45

◦

=

π

4

60

◦

=

π

3

120

◦

=

2

π

3

135

◦

=

3

π

4

150

◦

=

5

π

6

90

◦

=

π

2

180

◦

= π

210

◦

=

7

π

6

225

◦

=

5

π

4

240

◦

=

4

π

3

270

◦

=

3

π

2

300

◦

=

5

π

3

315

◦

=

7

π

4

330

◦

=

11

π

6

0

◦

=

0 radians

θ

hypotenuse

opp

osite

adjacen

t

0

(≡ 2π)

π

2

π

3

π

2

I

I

I

I

II

IV

θ

(

x, y)

x

y

r

7

π

6

reference

angle

reference

angle =

π

6

sin

+

sin −

cos

+

cos −

tan

+

tan −

A

S

T

C

7

π

4

9

π

13

5

π

6

(this

angle is

5π

6

clo

ckwise)

1

2

1

2

3

4

5

6

0

−

1

−

2

−

3

−

4

−

5

−

6

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

2π

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

3

π

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

3

π

2

π

π

2

y =

sin(x)

1

0

−

1

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

2π

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

2

π

3

π

2

π

π

2

y =

sin(x)

y =

cos(x)

−

π

2

π

2

y =

tan(x), −

π

2

<

x <

π

2

0

−

π

2

π

2

y =

tan(x)

−

2π

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

π

2

3

π

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

3

π

2

π

y =

sec(x)

y =

csc(x)

y =

cot(x)

y = f(

x)

−

1

1

2

y = g(

x)

3

y = h

(x)

4

5

−

2

f(

x) =

1

x

g(

x) =

1

x

2

etc.

0

1

π

1

2

π

1

3

π

1

4

π

1

5

π

1

6

π

1

7

π

g(

x) = sin

1

x

1

0

−

1

L

10

100

200

y =

π

2

y = −

π

2

y =

tan

−1

(x)

π

2

π

y =

sin(

x)

x

,

x > 3

0

1

−

1

a

L

f(

x) = x sin (1/x)

(0 <

x < 0.3)

h

(x) = x

g(

x) = −x

a

L

lim

x

→a

+

f(x) = L

lim

x

→a

+

f(x) = ∞

lim

x

→a

+

f(x) = −∞

lim

x

→a

+

f(x) DNE

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) = L

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) = ∞

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) = −∞

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) DNE

M

}

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) = M

lim

x

→a

f(x) = L

lim

x

→a

f(x) DNE

lim

x

→∞

f(x) = L

lim

x

→∞

f(x) = ∞

lim

x

→∞

f(x) = −∞

lim

x

→∞

f(x) DNE

lim

x

→−∞

f(x) = L

lim

x

→−∞

f(x) = ∞

lim

x

→−∞

f(x) = −∞

lim

x

→−∞

f(x) DNE

lim

x →a

+

f(

x) = ∞

lim

x →a

+

f(

x) = −∞

lim

x →a

−

f(

x) = ∞

lim

x →a

−

f(

x) = −∞

lim

x →a

f(

x) = ∞

lim

x →a

f(

x) = −∞

lim

x →a

f(

x) DNE

y = f(

x)

a

y =

|

x|

x

1

−

1

y =

|

x + 2|

x +

2

1

−

1

−

2

1

2

3

4

a

a

b

y = x sin

1

x

y = x

y = −

x

a

b

c

d

C

a

b

c

d

−

1

0

1

2

3

time

y

t

u

(

t, f (t))

(

u, f (u))

time

y

t

u

y

x

(

x, f (x))

y = |

x|

(

z, f(z))

z

y = f(

x)

a

tangen

t at x = a

b

tangen

t at x = b

c

tangen

t at x = c

y = x

2

tangen

t

at x = −

1

u

v

uv

u +

∆u

v +

∆v

(

u + ∆u)(v + ∆v)

∆

u

∆

v

u

∆v

v∆

u

∆

u∆v

y = f(

x)

1

2

−

2

y = |

x

2

− 4|

y = x

2

− 4

y = −

2x + 5

y = g(

x)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

−

1

−

2

−

3

−

4

−

5

−

6

y = f (

x)

3

−

3

3

−

3

0

−

1

2

easy

hard

flat

y = f

0

(

x)

3

−

3

0

−

1

2

1

−

1

y =

sin(x)

y = x

x

A

B

O

1

C

D

sin(

x)

tan(

x)

y =

sin

(x)

x

π

2

π

1

−

1

x =

0

a =

0

x

> 0

a

> 0

x

< 0

a

< 0

rest

position

+

−

y = x

2

sin

1

x

N

A

B

H

a

b

c

O

H

A

B

C

D

h

r

R

θ

1000

2000

α

β

p

h

y = g(

x) = log

b

(x)

y = f(

x) = b

x

y = e

x

5

10

1

2

3

4

0

−

1

−

2

−

3

−

4

y =

ln(x)

y =

cosh(x)

y =

sinh(x)

y =

tanh(x)

y =

sech(x)

y =

csch(x)

y =

coth(x)

1

−

1

y = f(

x)

original

function

in

verse function

slop

e = 0 at (x, y)

slop

e is infinite at (y, x)

−

108

2

5

1

2

1

2

3

4

5

6

0

−

1

−

2

−

3

−

4

−

5

−

6

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

2π

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

3

π

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

3

π

2

π

π

2

y =

sin(x)

1

0

−

1

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

2π

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

2

π

3

π

2

π

π

2

y =

sin(x)

y =

sin(x), −

π

2

≤ x ≤

π

2

−

2

−

1

0

2

π

2

−

π

2

y =

sin

−1

(x)

y =

cos(x)

π

π

2

y =

cos

−1

(x)

−

π

2

1

x

α

β

y =

tan(x)

y =

tan(x)

1

y =

tan

−1

(x)

y =

sec(x)

y =

sec

−1

(x)

y =

csc

−1

(x)

y =

cot

−1

(x)

1

y =

cosh

−1

(x)

y =

sinh

−1

(x)

y =

tanh

−1

(x)

y =

sech

−1

(x)

y =

csch

−1

(x)

y =

coth

−1

(x)

(0

, 3)

(2

, −1)

(5

, 2)

(7

, 0)

(

−1, 44)

(0

, 1)

(1

, −12)

(2

, 305)

y =

1

2

(2

, 3)

y = f(

x)

y = g(

x)

a

b

c

a

b

c

s

c

0

c

1

(

a, f (a))

(

b, f (b))

1

2

1

2

3

4

5

6

0

−

1

−

2

−

3

−

4

−

5

−

6

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

2π

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

3

π

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

3

π

2

π

π

2

y =

sin(x)

1

0

−

1

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

2π

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

2

π

3

π

2

π

π

2

c

OR

Lo

cal maximum

Lo

cal minimum

Horizon

tal point of inflection

1

e

y = f

0

(

x)

y = f (

x) = x ln(x)

−

1

e

?

y = f(

x) = x

3

y = g(

x) = x

4

x

f(

x)

−

3

−

2

−

1

0

1

2

1

2

3

4

+

−

?

1

5

6

3

f

0

(

x)

2 −

1

2

√

6

2

+

1

2

√

6

f

00

(

x)

7

8

g

00

(

x)

f

00

(

x)

0

y =

(

x − 3)(x − 1)

2

x

3

(

x + 2)

y = x ln

(x)

1

e

−

1

e

5

−

108

2

α

β

2 −

1

2

√

6

2

+

1

2

√

6

y = x

2

(

x − 5)

3

−

e

−

1/2

√

3

e

−

1/2

√

3

−

e

−3/2

e

−

3/2

−

1

√

3

1

√

3

−

1

1

y = xe

−

3x

2

/2

y =

x

3

− 6

x

2

+ 13x − 8

x

28

2

600

500

400

300

200

100

0

−

100

−

200

−

300

−

400

−

500

−

600

0

10

−

10

5

−

5

20

−

20

15

−

15

0

4

5

6

x

P

0

(

x)

+

−

−

existing

fence

new

fence

enclosure

A

h

b

H

99

100

101

h

dA/dh

r

h

1

2

7

shallo

w

deep

LAND

SEA

N

y

z

s

t

3

11

9

L

(11)

√

11

y = L

(x)

y = f (

x)

11

y = L

(x)

y = f(

x)

F

P

a

a +

∆x

f(

a + ∆x)

L

(a + ∆x)

f(

a)

error

d

f

∆

x

a

b

y = f(

x)

true

zero

starting

approximation

b

etter approximation

v

t

3

5

50

40

60

4

20

30

25

t

1

t

2

t

3

t

4

t

n

−2

t

n

−1

t

0

= a

t

n

= b

v

1

v

2

v

3

v

4

v

n

−1

v

n

−

30

6

30

|

v|

a

b

p

q

c

v(

c)

v(

c

1

)

v(

c

2

)

v(

c

3

)

v(

c

4

)

v(

c

5

)

v(

c

6

)

t

1

t

2

t

3

t

4

t

5

c

1

c

2

c

3

c

4

c

5

c

6

t

0

=

a

t

6

=

b

t

16

=

b

t

10

=

b

a

b

x

y

y = f(

x)

1

2

y = x

5

0

−

2

y =

1

a

b

y =

sin(x)

π

−

π

0

−1

−2

0

2

4

y = x

2

0

1

2

3

4

2

n

4

n

6

n

2(n−2)

n

2(n−1)

n

2n

n

= 2

width of each interval =

2

n

−2

1

3

0

I

II

III

IV

4

y

dx

y = −x

2

− 2x + 3

3

−5

y = |−x

2

− 2x + 3|

I

II

IIa

5

3

0

1

2

a

b

y = f (x)

y = g(x)

y = x

2

a

b

5

3

0

1

2

y =

√

x

2

√

2

2

2

dy

x

2

a

b

y = f(x)

y = g(x)

M

m

1

2

−1

−2

0

y = e

−x

2

1

2

e

−1/4

f

av

y = f

av

c

A

M

0

1

2

a

b

x

t

y = f(t)

F (x )

y = f(t)

F (x + h)

x + h

F (x + h) − F (x)

f(x)

1

2

y = sin(x)

π

−π

−1

−2

y =

1

x

y = x

2

1

2

1

−1

y = ln|x|

θ

a

x

a

x

p

a

2

− x

2

3

x

p

9 − x

2

p

x

2

+ a

2

x

a

p

x

2

+ 15

x

√

15

x

p

x

2

− a

2

a

x

p

x

2

− 4

2

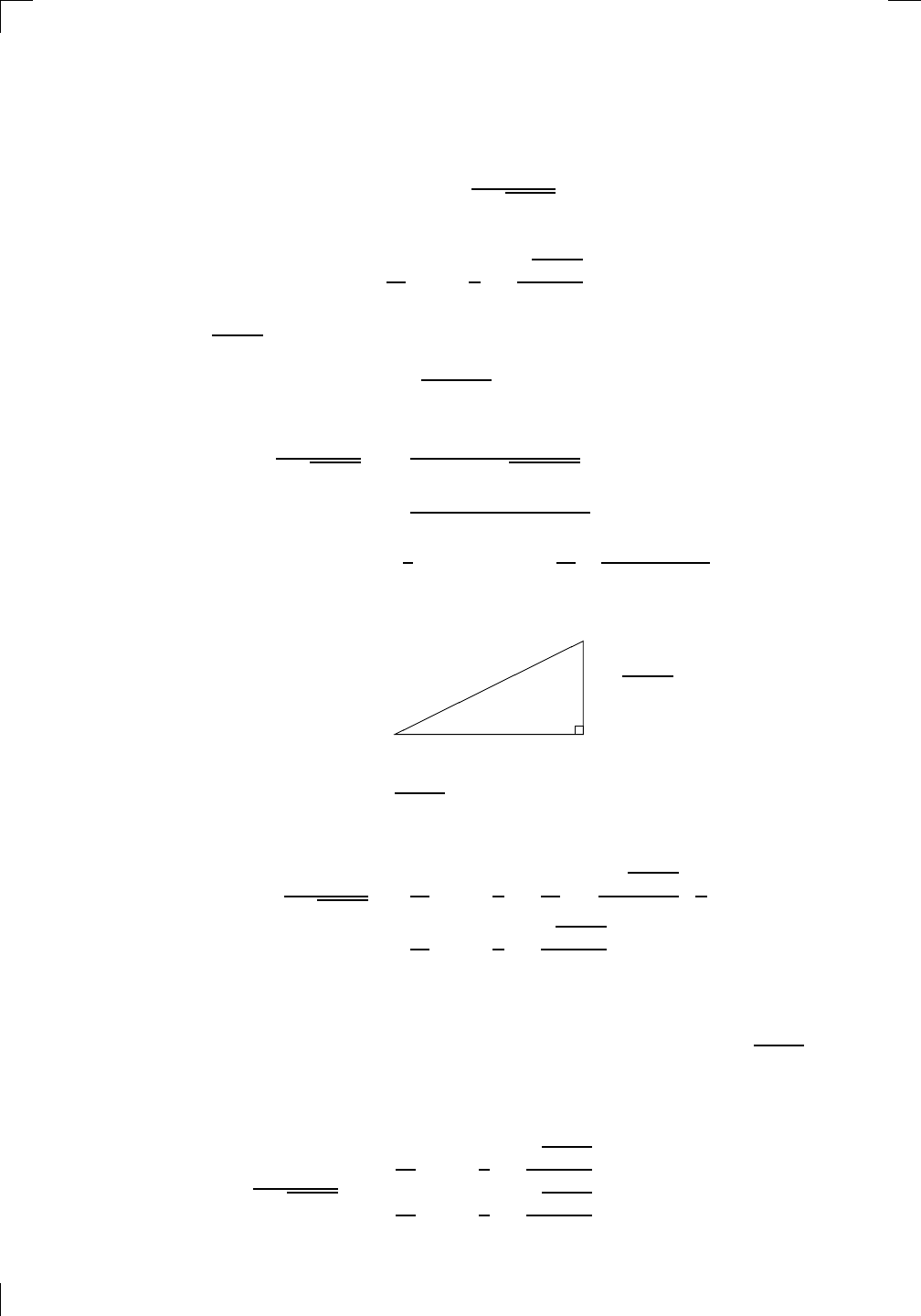

a

x

p

a

2

− x

2

PSfrag

replacements

(

a, b)

[

a, b]

(

a, b]

[

a, b)

(

a, ∞)

[

a, ∞)

(

−∞, b)

(

−∞, b]

(

−∞, ∞)

{

x : a < x < b}

{

x : a ≤ x ≤ b}

{

x : a < x ≤ b}

{

x : a ≤ x < b}

{

x : x ≥ a}

{

x : x > a}

{

x : x ≤ b}

{

x : x < b}

R

a

b

shado

w

0

1

4

−

2

3

−

3

g(

x) = x

2

f(

x) = x

3

g(

x) = x

2

f(

x) = x

3

mirror

(y = x)

f

−

1

(x) =

3

√

x

y = h

(x)

y = h

−

1

(x)

y =

(x − 1)

2

−

1

x

Same

height

−

x

Same

length,

opp

osite signs

y = −

2x

−

2

1

y =

1

2

x − 1

2

−

1

y =

2

x

y =

10

x

y =

2

−x

y =

log

2

(x)

4

3

units

mirror

(x-axis)

y = |

x|

y = |

log

2

(x)|

θ radians

θ units

30

◦

=

π

6

45

◦

=

π

4

60

◦

=

π

3

120

◦

=

2

π

3

135

◦

=

3

π

4

150

◦

=

5

π

6

90

◦

=

π

2

180

◦

= π

210

◦

=

7

π

6

225

◦

=

5

π

4

240

◦

=

4

π

3

270

◦

=

3

π

2

300

◦

=

5

π

3

315

◦

=

7

π

4

330

◦

=

11

π

6

0

◦

=

0 radians

θ

hypotenuse

opp

osite

adjacen

t

0

(≡ 2π)

π

2

π

3

π

2

I

I

I

I

II

IV

θ

(

x, y)

x

y

r

7

π

6

reference

angle

reference

angle =

π

6

sin

+

sin −

cos

+

cos −

tan

+

tan −

A

S

T

C

7

π

4

9

π

13

5

π

6

(this

angle is

5π

6

clo

ckwise)

1

2

1

2

3

4

5

6

0

−

1

−

2

−

3

−

4

−

5

−

6

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

2π

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

3

π

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

3

π

2

π

π

2

y =

sin(x)

1

0

−

1

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

2π

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

2

π

3

π

2

π

π

2

y =

sin(x)

y =

cos(x)

−

π

2

π

2

y =

tan(x), −

π

2

<

x <

π

2

0

−

π

2

π

2

y =

tan(x)

−

2π

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

π

2

3

π

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

3

π

2

π

y =

sec(x)

y =

csc(x)

y =

cot(x)

y = f(

x)

−

1

1

2

y = g(

x)

3

y = h

(x)

4

5

−

2

f(

x) =

1

x

g(

x) =

1

x

2

etc.

0

1

π

1

2

π

1

3

π

1

4

π

1

5

π

1

6

π

1

7

π

g(

x) = sin

1

x

1

0

−

1

L

10

100

200

y =

π

2

y = −

π

2

y =

tan

−1

(x)

π

2

π

y =

sin(

x)

x

,

x > 3

0

1

−

1

a

L

f(

x) = x sin (1/x)

(0 <

x < 0.3)

h

(x) = x

g(

x) = −x

a

L

lim

x

→a

+

f(x) = L

lim

x

→a

+

f(x) = ∞

lim

x

→a

+

f(x) = −∞

lim

x

→a

+

f(x) DNE

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) = L

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) = ∞

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) = −∞

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) DNE

M

}

lim

x

→a

−

f(x) = M

lim

x

→a

f(x) = L

lim

x

→a

f(x) DNE

lim

x

→∞

f(x) = L

lim

x

→∞

f(x) = ∞

lim

x

→∞

f(x) = −∞

lim

x

→∞

f(x) DNE

lim

x

→−∞

f(x) = L

lim

x

→−∞

f(x) = ∞

lim

x

→−∞

f(x) = −∞

lim

x

→−∞

f(x) DNE

lim

x →a

+

f(

x) = ∞

lim

x →a

+

f(

x) = −∞

lim

x →a

−

f(

x) = ∞

lim

x →a

−

f(

x) = −∞

lim

x →a

f(

x) = ∞

lim

x →a

f(

x) = −∞

lim

x →a

f(

x) DNE

y = f (

x)

a

y =

|

x|

x

1

−

1

y =

|

x + 2|

x +

2

1

−

1

−

2

1

2

3

4

a

a

b

y = x sin

1

x

y = x

y = −

x

a

b

c

d

C

a

b

c

d

−

1

0

1

2

3

time

y

t

u

(

t, f (t))

(

u, f (u))

time

y

t

u

y

x

(

x, f (x))

y = |

x|

(

z, f(z))

z

y = f(

x)

a

tangen

t at x = a

b

tangen

t at x = b

c

tangen

t at x = c

y = x

2

tangen

t

at x = −

1

u

v

uv

u +

∆u

v +

∆v

(

u + ∆u)(v + ∆v)

∆

u

∆

v

u

∆v

v∆

u

∆

u∆v

y = f(

x)

1

2

−

2

y = |

x

2

− 4|

y = x

2

− 4

y = −

2x + 5

y = g(

x)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

−

1

−

2

−

3

−

4

−

5

−

6

y = f (

x)

3

−

3

3

−

3

0

−

1

2

easy

hard

flat

y = f

0

(

x)

3

−

3

0

−

1

2

1

−

1

y =

sin(x)

y = x

x

A

B

O

1

C

D

sin(

x)

tan(

x)

y =

sin

(x)

x

π

2

π

1

−

1

x =

0

a =

0

x

> 0

a

> 0

x

< 0

a

< 0

rest

position

+

−

y = x

2

sin

1

x

N

A

B

H

a

b

c

O

H

A

B

C

D

h

r

R

θ

1000

2000

α

β

p

h

y = g(

x) = log

b

(x)

y = f(

x) = b

x

y = e

x

5

10

1

2

3

4

0

−

1

−

2

−

3

−

4

y =

ln(x)

y =

cosh(x)

y =

sinh(x)

y =

tanh(x)

y =

sech(x)

y =

csch(x)

y =

coth(x)

1

−

1

y = f(

x)

original

function

in

verse function

slop

e = 0 at (x, y)

slop

e is infinite at (y, x)

−

108

2

5

1

2

1

2

3

4

5

6

0

−

1

−

2

−

3

−

4

−

5

−

6

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

2π

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

3

π

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

3

π

2

π

π

2

y =

sin(x)

1

0

−

1

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

2π

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

2

π

3

π

2

π

π

2

y =

sin(x)

y =

sin(x), −

π

2

≤ x ≤

π

2

−

2

−

1

0

2

π

2

−

π

2

y =

sin

−1

(x)

y =

cos(x)

π

π

2

y =

cos

−1

(x)

−

π

2

1

x

α

β

y =

tan(x)

y =

tan(x)

1

y =

tan

−1

(x)

y =

sec(x)

y =

sec

−1

(x)

y =

csc

−1

(x)

y =

cot

−1

(x)

1

y =

cosh

−1

(x)

y =

sinh

−1

(x)

y =

tanh

−1

(x)

y =

sech

−1

(x)

y =

csch

−1

(x)

y =

coth

−1

(x)

(0

, 3)

(2

, −1)

(5

, 2)

(7

, 0)

(

−1, 44)

(0

, 1)

(1

, −12)

(2

, 305)

y =

1

2

(2

, 3)

y = f(

x)

y = g(

x)

a

b

c

a

b

c

s

c

0

c

1

(

a, f (a))

(

b, f (b))

1

2

1

2

3

4

5

6

0

−

1

−

2

−

3

−

4

−

5

−

6

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

2π

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

3

π

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

3

π

2

π

π

2

y =

sin(x)

1

0

−

1

−

3π

−

5

π

2

−

2π

−

3

π

2

−

π

−

π

2

3

π

5

π

2

2

π

2

π

3

π

2

π

π

2

c

OR

Lo

cal maximum

Lo

cal minimum

Horizon

tal point of inflection

1

e

y = f

0

(

x)

y = f (

x) = x ln(x)

−

1

e

?

y = f(

x) = x

3

y = g(

x) = x

4

x

f(

x)

−

3

−

2

−

1

0

1

2

1

2

3

4

+

−

?

1

5

6

3

f

0

(

x)

2 −

1

2

√

6

2

+

1

2

√

6

f

00

(

x)

7

8

g

00

(

x)

f

00

(

x)

0

y =

(

x − 3)(x − 1)

2

x

3

(

x + 2)

y = x ln(

x)

1

e

−

1

e

5

−

108

2

α

β

2 −

1

2

√

6

2

+

1

2

√

6

y = x

2

(

x − 5)

3

−

e

−

1/2

√

3

e

−

1/2

√

3

−

e

−3/2

e

−

3/2

−

1

√

3

1

√

3

−

1

1

y = xe

−

3x

2

/2

y =

x

3

− 6

x

2

+ 13x − 8

x

28

2

600

500

400

300

200

100

0

−

100

−

200

−

300

−

400

−

500

−

600

0

10

−

10

5

−

5

20

−

20

15

−

15

0

4

5

6

x

P

0

(

x)

+

−

−

existing

fence

new

fence

enclosure

A

h

b

H

99

100

101

h

dA/dh

r

h

1

2

7

shallo

w

deep

LAND

SEA

N

y

z

s

t

3

11

9

L

(11)

√

11

y = L

(x)

y = f (

x)

11

y = L

(x)

y = f(

x)

F

P

a

a +

∆x

f(

a + ∆x)

L

(a + ∆x)

f(

a)

error

d

f

∆

x

a

b

y = f(

x)

true

zero

starting

approximation

b

etter approximation

v

t

3

5

50

40

60

4

20

30

25

t

1

t

2

t

3

t

4

t

n

−2

t

n

−1

t

0

= a

t

n

= b

v

1

v

2

v

3

v

4

v

n

−1

v

n

−

30

6

30

|

v|

a

b

p

q

c

v(

c)

v(

c

1

)

v(

c

2

)

v(

c

3

)

v(

c

4

)

v(

c

5

)

v(

c

6

)

t

1

t

2

t

3

t

4

t

5

c

1

c

2

c

3

c

4

c

5

c

6

t

0

=

a

t

6

=

b

t

16

=

b

t

10

=

b

a

b

x

y

y = f(

x)

1

2

y = x

5

0

−

2

y =

1

a

b

y =

sin(x)

π

−

π

0

−

1

−

2

0

2

4

y = x

2

0

1

2

3

4

2

n

4

n

6

n

2(n−2)

n

2(n−1)

n

2n

n

= 2

width of each interval =

2

n

−2

1

3

0

I

II

III

IV

4

y

dx

y = −x

2

− 2x + 3

3

−5

y = |−x

2

− 2x + 3|

I

II

IIa

5

3

0

1

2

a

b

y = f (x)

y = g(x)

y = x

2

a

b

5

3

0

1

2

y =

√

x

2

√

2

2

2

dy

x

2

a

b

y = f(x)

y = g(x)

M

m

1

2

−1

−2

0

y = e

−x

2

1

2

e

−1/4

f

av

y = f

av

c

A

M

0

1

2

a

b

x

t

y = f(t)

F (x )

y = f(t)

F (x + h)

x + h

F (x + h) − F (x)

f(x)

1

2

y = sin(x)

π

−π

−1

−2

y =

1

x

y = x

2

1

2

1

−1

y = ln|x|

θ

a

x

a

x

p

a

2

− x

2

3

x

p

9 − x

2

p

x

2

+ a

2

x

a

p

x

2

+ 15

x

√

15

x

p

x

2

− a

2

a

x

p

x

2

− 4

2

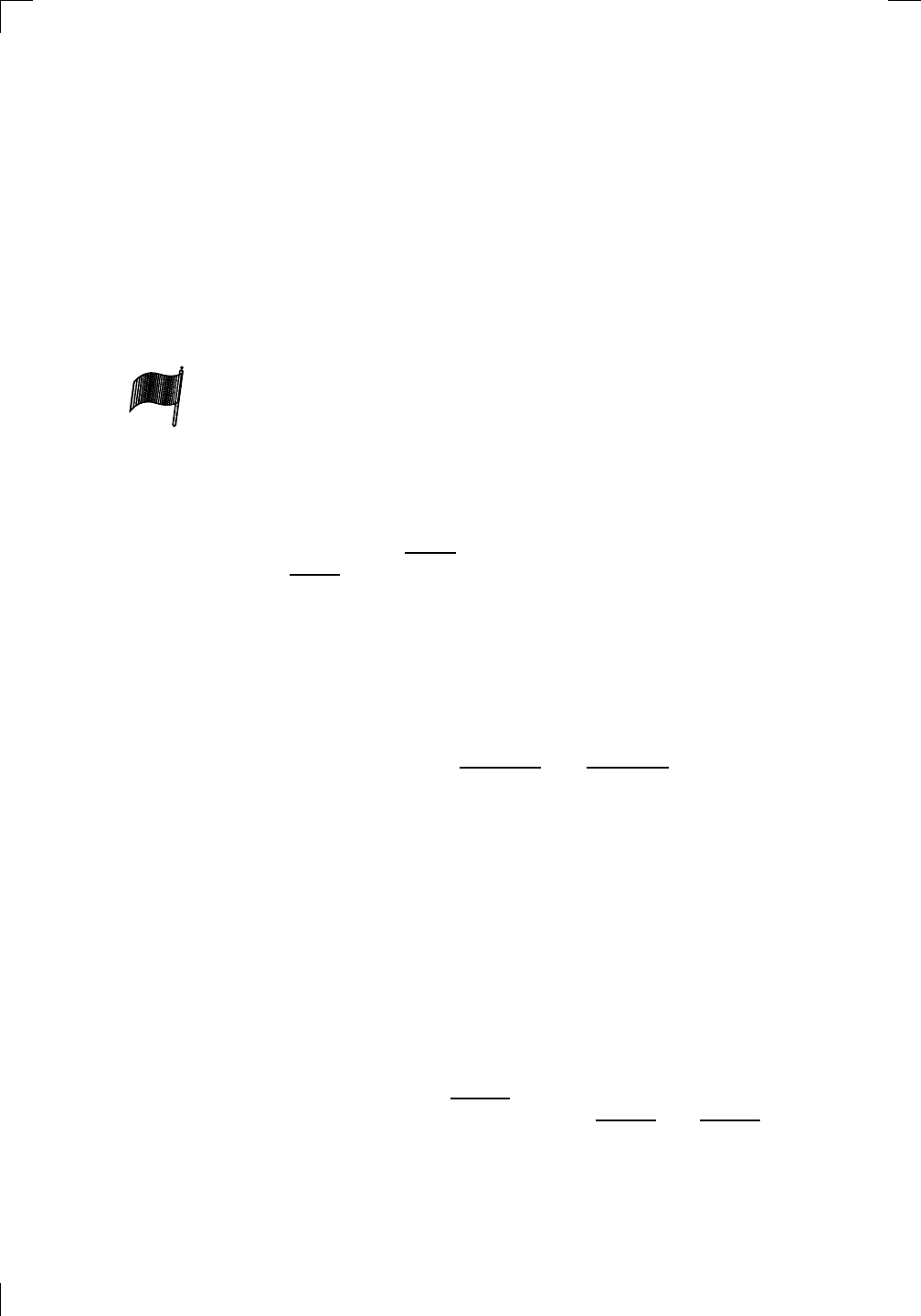

p

x

2

+ a

2

x

a

PSfrag

replacements

(

a, b)

[

a, b]

(

a, b]

[

a, b)

(

a, ∞)

[

a, ∞)

(

−∞, b)

(

−∞, b]

(

−∞, ∞)

{

x : a < x < b}

{

x : a ≤ x ≤ b}

{

x : a < x ≤ b}

{

x : a ≤ x < b}

{

x : x ≥ a}

{

x : x > a}

{

x : x ≤ b}

{

x : x < b}

R

a

b

shado

w

0

1

4

−

2

3

−

3

g(

x) = x

2

f(

x) = x

3

g(

x) = x

2

f(

x) = x

3

mirror

(y = x)

f

−

1

(x) =

3

√

x

y = h

(x)

y = h

−

1

(x)

y =

(x − 1)

2

−

1

x

Same

height

−

x

Same

length,

opp

osite signs

y = −

2x

−

2

1

y =

1

2

x − 1

2

−

1

y =

2

x

y =

10

x

y =

2

−x

y =

log

2

(x)

4

3

units

mirror

(x-axis)

y = |

x|

y = |

log

2

(x)|

θ radians

θ units

30

◦

=

π

6

45

◦

=

π

4

60

◦

=

π

3

120

◦

=

2

π

3

135

◦

=

3

π

4

150

◦

=

5

π

6

90

◦

=

π

2

180

◦

= π

210

◦

=

7

π

6

225

◦

=

5

π

4

240

◦

=

4

π

3

270

◦

=

3

π

2

300

◦

=

5

π

3

315

◦

=

7

π

4

330

◦

=

11

π

6

0

◦

=

0 radians

θ

hypotenuse

opp

osite

adjacen

t

0

(≡ 2π)

π

2

π

3

π

2

I

I

I

I

II

IV

θ

(

x, y)

x

y

r

7

π

6

reference

angle

reference

angle =