Barr-Melej P. Reforming Chile: Cultural Politics, Nationalism, and the Rise of the Middle Class (ENG)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

122 Prose, Politics, and Patria

Marta Brunet became a significant member of

the criollista cohort upon the appearance of

her first work, Montaña adentro, in 1923. The

native of Chilláan was best known for her

narrative emphasis on women in her cuentos

and novels. (Courtesy of the Archivo Foto-

gráfico, Museo Histórico Nacional, Santiago)

anger building inside, unties and kicks the horse, which gallops away. Bru-

net’s prose reinforces criollismo’s message that campesinos, though poor, are

nonetheless physically and metaphysically linked to the rural landscape—a

space that is authentically Chilean.

Brunet contributed in no small way to criollismo’s popularity among urban

readers in the 1920s and 1930s. Yet some Chileans lamented the lack of a

single, great work of fiction on par with Argentine criollista Ricardo Güiral-

des’s Don Segundo Sombra (1925) that could capture the authentic Chile in a

definitive way. El Diario Ilustrado, which published numerous criollista short

stories and serials in the 1930s, praised Don Segundo Sombra as the ‘‘magnifi-

cent novel of the [Argentine] pampas, which has made us think, almost with

melancholy, of that great Chilean novel, a synthesis of the spirit of our race,

which is so late in arriving.’’

∑∑

In 1934, the criollista Joaquín Edwards Bello

made reference to José Hernández’s classic nineteenth-century Argentine

poem Martín Fierro when he complained: ‘‘What do we have to compare to

it? No, Don Lucas Gómez doesn’t work.’’

∑∏

Despite the lack of Chilean heroes

like the gauchos Segundo Sombra or Martín Fierro, the criollistas already had

begun to reshape Chile’s national identity.

A 1929 article in the Revista de Educación by one PR correligionario recognizes

the importance of lo rural in Chilean national identity. Citing Latorre, Gana,

and other authors, the reformer explains, ‘‘Now that Chileans begin to look

Prose, Politics, and Patria 123

with loving eyes upon the landscape our countryside offers, the beauties of

our ocean and all the magnificence of our native mountains, the writers that

have put forward this admiration feel the jubilation in what is in them a

flame of enthusiasm and love of this rugged land.’’ He goes on to state,

‘‘[These] writers have drawn close to their heart the native landscape, with its

trees, characteristic types, and customs that form the racial idiosyncrasy in

which an able pupil can find all of the avenues on which the highest of

emotions travel.’’

∑π

In an article concerning ‘‘la chilenidad literaria,’’ one critic

in El Diario Ilustrado stated in 1931 that ‘‘it seems as though the place where

chilenidad is most notably manifested is among the lower class, especially in

the countryside’’ and that criollismo’s goal was to produce ‘‘books that are

specifically national.’’

∑∫

Some forty years earlier, the semibarbaric, embar-

rassing, and ridiculed campesino Lucas Gómez (the character in Martínez

Quevedo’s Don Lucas Gómez, o sea, un huaso en Santiago) was a widely popular

representation of the rural underclass’s characteristics. Criollismo did much

to change perceptions of the campo and campesinos in urban society.

The criollista literature of Joaquín Edwards Bello bolstered the genre’s

place in Chile’s cultural life during the 1920s and 1930s. The great-grandson

of Andrés Bello, Edwards Bello (1887–1968) was a member of the affluent

Edwards clan that owned, and owns, the newspaper El Mercurio. He was

raised in Valparaíso before moving to Santiago, where he began a long career

as a journalist and writer of fiction and nonfiction. Coming from the coun-

try’s major port, he arrived in the capital already aware of the social question

and its many implications. Outside criollismo, Edwards Bello expressed his

views while working as a columnist for La Nación (his weekly columns were

quite popular). A member of the PR since 1912, he regularly echoed the ideas

of his party on issues such as education, national characteristics, and patrio-

tism, though he, like Latorre, claimed to be ‘‘apolitical.’’

∑Ω

Edwards Bello

became a widely recognized author upon the publication in 1920 of his first

major book, El roto, a short criollista novel set in urban society that exhibits

naturalism’s considerable penetration into Chilean literary culture.

∏≠

El roto’s appearance coincided with the fervor of a presidential election in

which the AL and Alessandri ran a populistic campaign, and the novel cer-

tainly has something to say about socioeconomic and political problems

addressed by the reformist alessandristas. Filled with descriptions of charac-

ters and objects, the novel focuses on ‘‘humble’’ Chileans, the author ex-

plains. These are the ‘‘rotos’’—urban and rural mestizos, including huasos,

miners, and even ruffians—who are subject to the imperious power of the

elite.

∏∞

Indeed, roto means ‘‘broken’’ or ‘‘damaged.’’ They are the broken peo-

124 Prose, Politics, and Patria

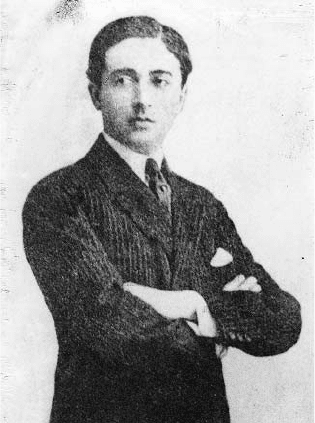

A reformer of aristocratic stock, a young

Joaquín Edwards Bello published his first

major work, El roto, in 1920 and became one

of the foremost Chilean intellectuals of the

1930s and 1940s as a newspaper columnist,

essayist, and novelist. (Courtesy of the

Consocio Periodístico, S.A. [Copesa], and La

Tercera, Santiago)

ple. They are men like Esmeraldo and Fernando. Esmeraldo’s mother raises

him in a brothel, while Fernando is a hard worker with hope for a better life

but learns that upward mobility is illusory in the rigid hierarchy of a tradi-

tional society. The elite, meanwhile, is frivolous and corrupt, as demon-

strated by the character Pantaleón Madroño, a senator, whose morality

(public and private) is quite clearly ‘‘broken.’’

∏≤

As one literary critic noted,

such aspects of society (especially those associated with its underbelly) were

unknown to, or ignored by, the residents of Santiago’s finest neighborhoods

and most opulent homes.

∏≥

The criollista thus expanded the narrative param-

eters of Chile’s social experience and, in the form of the roto, offered readers a

complex look at chilenidad. One also understands from Edwards Bello that

many of the rotos’ negative traits, such a propensity toward violence, gam-

bling, and sexual hedonism, can be attributed to the prevailing socioeco-

nomic, political, and cultural circumstances of the Parliamentary Republic.

Conditions associated with the social question, for example, loom over the

underclass in El roto. Edwards Bello, who is known to have anonymously

wandered through poor neighborhoods to witness living and working con-

ditions for himself, continued to write about this subject in later years.

In 1933, Edwards Bello blamed the ongoing social question on a central

flaw of the Chilean character. While acknowledging the material differences

among social groups, he explains that ‘‘it is easy to live one’s life protesting’’

and that in Chile ‘‘everyone wants what they do not have.’’ He essentially

Prose, Politics, and Patria 125

states that a solution to the social question lay not only in material matters

but also in attitude.

∏∂

A 1932 column explains that a principal national char-

acteristic is envy, which only leads, ‘‘bit by bit, to ruin.’’ Another trait is a

proclivity for disorder, which fertilizes revolutionary thought among work-

ers. Edwards Bello suggests, however, that Chilean workers are not to blame:

‘‘At heart, our pueblo, our popular masses have great worth, more than what

people think. But yes, it is a pueblo poisoned by the evil prophets [perhaps

communists?]. . . . In general, our pueblo, that is so say, the worker, is basically

bourgeois, in the deepest sense.’’

∏∑

The notion that Chilean workers are good

but easily misled commonly circulated among reformers during this era. As

we shall see in subsequent chapters, reformers considered public education a

sphere in which Chileans could be led down a more correct path through the

dissemination of culture and the spread of a nationalist sensibility.

∏∏

The aristocracy was not immune to character flaws either, Edwards Bello

argued. In a 1937 column, the criollista criticized the elite who found no

redeeming values in Chilean civilization—those who ventured abroad and

criticized their homeland. ‘‘The Chilean only rarely knows how to give him-

self importance,’’ he explained. It was common, moreover, for those of the

elite to value Paris or London more than Santiago, and Edwards Bello makes

an example of a ‘‘young girl [who] pretends to be chic, elegant, and modern.

Please don’t think she is a stupid huasa!’’

∏π

With wit and a sharp tongue,

Edwards Bello suggests that the young girl does not want to be identified

with a typical Chilean, a huasa, but rather with a culture foreign to her. Like

Latorre, who in Cuentos del Maule described Chileans who want to act Euro-

pean, Edwards Bello demonstrates a nationalism that values, in a round-

about way, Chile’s authentic traditions and heritage; the huasa is lo chileno

and should not be the subject of ridicule.

The notion of authenticity lies at the heart of La chica del Crillón, which, in

large part, won Edwards Bello the 1943 National Literature Award. The novel

helped lift lo rural (or urban perceptions of it) and the huaso mystique to

national attention and acclaim in the 1930s. La chica del Crillón (the Crillón

was a French-style luxurious hotel in downtown Santiago) is the story of an

upper-class urban girl, Teresa Iturrigorriaga (not her real name, she admits

to the reader), who attempts and fails to maintain the flamboyant and ex-

pensive lifestyle typical of the capital’s elite after her father’s financial ruin

and her mother’s death. Near the end of the novel, Iturrigorriaga, on her

journey near the coastal city of Viña del Mar, confronts Ramón Ortega

Urrutia and is swept off her feet by this man of the countryside with an inner

strength characteristic of criollismo protagonists. He wears huaso attire and,

126 Prose, Politics, and Patria

as the author describes, is a species far ‘‘healthier and stronger . . . than the

weak and sickly men of the city.’’

∏∫

One of Edwards Bello’s contemporaries,

Raúl Silva Castro, commented that Ortega appears in the story as a super-

natural apparition, helping the young woman to fend off the cruelties of

life.

∏Ω

Ortega’s kind demeanor toward the helpless—or hapless—Iturrigorriaga

represents a provincial morality that stands in sharp contrast to the deca-

dence of Santiago.

π≠

Iturrigorriaga warmly describes Ortega in this way: ‘‘His

words were so filled with nobility and security, that I threw caution to the

wind and, sitting on the haunch of his horse, I grabbed the reins and began

to gallop.’’

π∞

From the back of a horse, Ortega introduces Iturrigorriaga to a

wondrous environment she had never explored. As the urban girl states

when Ortega makes his way off into the countryside at dusk, ‘‘An immense,

unknown tenderness made my heart swell. I lay down on the ground with-

out a word; I saw nothing but his shadow slowly getting further away; the

stars were near, near, more near than ever before. A great smell of the

countryside, of grass, of nature, induced sleepiness; far-away frogs sang at

the stream and, at the same time, other sounds of waterfalls, of broken

branches, of nocturnal rodents, of the horses who stomped around search-

ing for grass, formed a concert infinitely more dignified than a jazz band.’’

π≤

To Iturrigorriaga, the harmonies of pastoral life are decidedly more Chilean

than those of the saxophone or trumpet. Like the music of the zamacueca (or

cueca, for short), the symphony of nature is authentic and comforting. Thus,

Ortega, to whom the author ascribes ‘‘huaso’’ traits, and his environment

exemplify what Edwards Bello and others hailed as features of chilenidad.

The Ortega character devised by Edwards Bello is certainly not a ‘‘com-

mon’’ huaso. This horseman is not a poor campesino but rather a more

affluent huaso (similar to Durand’s Miguel Rodríguez in ‘‘Humitas’’) and

even bears the maternal last name Urrutia, an uncommon name among the

lower classes. Ortega is, in fact, not only the ‘‘bourgeois’’ campesino Ed-

wards Bello imagined in his 1932 column in La Nación but also a landowner

with workers under him. How can we explain Edwards Bello’s literary con-

struction of a well-to-do huaso? We see in Ortega the fusion of lower-class,

‘‘huaso’’ characteristics that criollistas cast as typically chileno (including the

horseman’s clothes that make Teresa swoon) with a more affluent represen-

tative of the rural populace—the blending of a populistic and mesocratic

construction with a more prosperous persona. It is clear from his many

writings that Edwards Bello held a high opinion of Chile’s popular classes

but also respected the participation of landowners and other elements of the

Prose, Politics, and Patria 127

elite in a democratic society. Reformers generally shared this view but cer-

tainly envisioned themselves in charge. Of most interest here, however, is the

fact that when Edwards Bello was writing La chica del Crillón, reformers were

coalition partners of Alessandri and had joined Liberals and Conservatives

against the rising Socialists and Communists in the election of 1932. Indeed,

the negative vibes of worker unrest in the countryside form a component of

Edwards Bello’s novel, which says much about the reformers’ and tradi-

tionalists’ meeting of the minds on the issue during the 1930s.

Much to the chagrin of Iturrigorriaga, the campesinos of the region be-

tween Santiago and Viña del Mar are in rebellion, and to make things worse,

there is a railroad strike brewing, making it difficult for people to flee the

instability. In fact, Iturrigorriaga finds herself stranded on a train with dan-

ger all around (campesinos armed with rudimentary weapons!) until she is

rescued from the predicament by Ortega, who comes into sight on horse-

back and takes the naive santiaguina to safety. These campesino rebels stand

in sharp contrast to Ortega, who, Edwards Bello suggests, is more ‘‘Chil-

ean’’—more huaso—than those incited to insurrection (perhaps by commu-

nist agitators or leftist politicians such as Grove or Lafertte?). Thus, this

literary complexity rather effectively reflects the broader political situation

at the time, which saw increased labor unrest in the countryside and a short-

lived Radical-Liberal-Conservative antirevolutionary alliance immediately

after the failed Socialist Republic.

A columnist who reviewed La chica del Crillón for El Diario Ilustrado, a jour-

nalistic voice of the Right, wrote: ‘‘Teresa Iturrigorriaga . . . ends up as a good

young lady in a home without fantasy and with a man in whom she sees cer-

tain moral traits. . . . Does all of this represent a return to the countryside?’’

π≥

It did, symbolically speaking. El Diario Ilustrado’s praise of La chica del Crillón

and the newspaper’s periodic printing of criollista short stories in the 1930s

points to a significant development in the history of genre: the diffusion of

its images and sentiments throughout the public sphere. A nation’s sym-

bolic ‘‘return to the countryside’’ was at hand, and criollismo-inspired rural

aestheticism was to play different roles for competing political interests.

π∂

Interpreting Criollismo: Urban Politics

and Visions of the Countryside

During most of the Parliamentary Republic, three major parties formed the

core of Chile’s political arena: the PL, the PC, and the PR. By the 1930s,

128 Prose, Politics, and Patria

Socialists and their largely middle-class leadership had joined the ongoing

contest, as had the PCCh and the small but boisterous MNS. Thus, politics

became a much more crowded place after the Parliamentary Republic, and

competitors were anxious to build or augment solid electoral constituen-

cies. Images and sentiments like those captured in print by the criollistas

became components of an array of political discourses as interest groups

sought to legitimize further their agendas and ideologies by demonstrating

their approximation to chilenidad. During the 1930s both Right and Left

constructed derivatives of an aestheticism that had originally emerged as

a narrative projection of middle-class reformism. This diffusion demon-

strated the genre’s far-reaching influence in Chilean society, as democratized

concepts of who and what constituted Chile proliferated across class and

party lines, at least discursively. Groups staked claims to the huaso construct

(as well as the generic ‘‘roto’’ to some degree) and asserted that they under-

stood the rural existence more than their competitors. No longer were in-

ferences to authentic huasos and campesino lifeways merely facets of a subtle

narrative strategy infused with a unique cultural and political sensibility.

They became overt components of political discourses and the symbolic

universe of popular culture, and the once ridiculed campesino and his cul-

tural heritage came to represent lo chileno.

In newspapers, magazines, speeches, school textbooks, and other media,

urban Chileans of many political persuasions established discursive and

symbolic ties to a rural existence that many had never directly experienced.

In some cases, a rural identity was manifested in indirect and humorous

ways. Political cartoons in the satirical magazine Topaze, for example, used

huaso figures to represent political groups and often dressed caricatures of

well-known Chilean politicians in huaso clothes. One 1936 cartoon shows

huasos representing both the PC and the FP engaged in a zamacueca folk

dance with a young lady, the PR. Radicals, Topaze suggests, have no problem

socializing with more than one political group, and both Conservatives and

frentistas gaze upon the PR as a possible consort.

π∑

Moreover, Alessandri and

Aguirre Cerda appeared often in Topaze cartoons. A cartoon published in

1938 depicts Aguirre Cerda—with spurs, a chamanto, and the typical huaso

hat—on horseback attempting to rope a steer labeled ‘‘Ibañismo’’ during a

rodeo. The cartoon pokes fun at Aguirre Cerda’s move to gain the support of

Ibáñez and the APL in the 1938 presidential election and presents the na-

tion’s political sphere as a rodeo arena—a rough place with untamed ani-

mals.

π∏

Nearly all prominent political leaders are depicted in huaso attire at

one time or another in Topaze, which demonstrates quite effectively two de-

Prose, Politics, and Patria 129

velopments: the infusion of a rural identity into the overwhelmingly urban

political conversation of the early twentieth century, and signs that ‘‘huaso’’

was becoming a term that also suggested legitimacy. Topaze, it should be

added, poked fun at all political persuasions and was probably the most

humorous political publication of the era.

Of central importance here is how and why political interests constructed

rural identities for themselves and on their own terms. The ensuing tug-of-

war over chilenidad and rural images saw Liberals and Conservatives anchor-

ing one end of the rope, leftist groups that formed the FP anchoring the

opposite end, the PR grabbing on somewhere in between, and other political

groups trying to join the contest. Politicians and intellectuals to the right of

the PR seized on rural imagery with great enthusiasm, though it is impossi-

ble to say with certitude when this first occurred.

ππ

It is clear, however, that

images of huasos and allusions to the cultural worth of the countryside

became most apparent in the early 1930s across the board.

On the far right, the MNS, despite being the most nonrural party one

could possibly imagine, used the huaso to make a political point in the 1930s

(though the image of the urban ruffian, or ‘‘roto,’’ was more prevalent in

National Socialist propaganda). A cartoon published in the party’s maga-

zine, Acción Chilena, depicts a teeter-totter with a gluttonous capitalist on one

side and a hammer- and sickle-wielding Marxist on the other. A huaso, which

represents the MNS, approaches the teeter-totter and violently knocks the

capitalist and Marxist to the ground. The message is clear: the MNS—a truly

Chilean party and defender of the nation’s interest—offers a third way.

π∫

To

be sure, the more mainstream political groups of the 1930s used rural imag-

ery to a much greater extent than did the National Socialists.

Within the alessandrista camp, conservative nationalists, especially mem-

bers of the landowning elite associated with the National Agricultural So-

ciety (SNA), were particularly motivated to use rural social relations as an

example of the authentic Chile, given the fact that unionization began to

spread to the countryside during the 1920s. Landowners acknowledged

criollismo’s aesthetic appeal and used it. To the traditional elite, the lan-

guage of reformers and, in some cases, reform itself became political exigen-

cies. No circumstance convinced landowners of this reality more than rural

unionization.

Although Chilean rural society was bereft of far-reaching structural

change during the 1920s and 1930s, it nonetheless saw the beginning of what,

by the 1960s, became one of Latin America’s most formidable labor move-

ments enthused by revolutionary ideas. The rumbles of lower-class mobili-

130 Prose, Politics, and Patria

zation in the countryside certainly caught the attentions of the major politi-

cal interests between Alessandri’s first administration and the FP. Of course,

different political groups responded to incipient unionization in the coun-

tryside in different ways. As one would think, traditionalist Liberals and

Conservatives grew worried over the prospect of union organizers swarming

throughout the campo. At the same time, the organized Left (and, from time

to time, the Radicals) lauded the onset of what the newspaper Frente Popular

called ‘‘the conquest of the campo.’’

πΩ

Thus, although the working and living

conditions of urban workers had dominated political discussion about the

social question since the latter decades of the nineteenth century, political

groups and their media resources increasingly discussed rural labor after

about 1920, especially during periods of depressed agricultural production.

∫≠

Scholars such as Brian Loveman have studied unionization and varying

responses to it during the 1920s and 1930s. Without reproducing their de-

tailed findings here, it is apparent that the legalization in 1924 of labor

organizing in the countryside began a period of labor conflict that lasted

into the latter half of the century, though Loveman likely overstates the

reach of rural unionism before 1940.

∫∞

The only union to be granted legality

under the law was the Professional Syndicate of the Livestock and Cold-

Storage Industry (Sindicato Profesional de la Industria Ganadera y Frigo-

rífico) of Magallanes. No purely agricultural-based union was formed until

the promulgation of the Labor Code of 1931, though the FOCh remained

busy rallying support among campesinos during the final decade of the Par-

liamentary Republic.

∫≤

With a new labor code on the books during the early

years of Alessandri’s second term, unions became more visible in the coun-

tryside. Among the more prominent rural unions was the Poor Campesino

National Defense League (Liga Nacional de Defensa de Campesinos Pobres),

founded in 1935 by Emilio Zapata, a Trotskyist and congressional deputy. In

response to rural unionization efforts, the SNA officially lobbied the Ales-

sandri government to amend the Labor Code of 1931. In the meantime, land-

owners personally sought to curtail labor organizing on their properties.

∫≥

Alessandri’s posture toward rural labor was, in many ways, a mixed bag of

status quo politics and reformist aspirations. In 1933, the newly established

Ministry of Labor, in the spirit of the Labor Code of 1931, began granting

legal status to all qualified rural unions via an application process. The SNA,

the most powerful landowner-based organization in the country, expressed

its opposition in no uncertain terms, but two government review boards

upheld the grants of legality.

∫∂

Yet Alessandri, concerned with the impact of

rural unionization on landowners and their support for his government,

Prose, Politics, and Patria 131

temporarily suspended the legal inscription of agricultural unions. In 1935,

Alessandri proposed rural reform measures in part to make up for his deci-

sion to suspend legalization proceedings. By the mid-1930s, the Left and

reformist groups (including the PR) supported the idea of agrarian reform

by way of subdividing haciendas, and many within the SNA agreed that

some social reforms were needed to mitigate the possibility of social revo-

lution.

∫∑

They already had endorsed the concept of creating ‘‘new small-

property owners, who, as such, constitute the best base for social tran-

quillity.’’ This was to be done largely by ‘‘colonizing’’ lands not in use rather

than by expropriating existing properties.

∫∏

What Alessandri had in mind,

however, was not acceptable to SNA landowners. A new rural reform statute

was enacted that granted the government more authority over land and

strengthened its hand in matters of expropriation.

∫π

In practice, though,

little became of talk to alter land tenure in the countryside in the 1930s. The

same could be said of the FP’s policy toward rural matters during the presi-

dency of Aguirre Cerda.

The specter of rural unionization and campesino radicalization was a

major concern of the Alessandri government as the Left became more orga-

nized, memories of the Socialist Republic remained fresh, and landowners

pressured Alessandri regarding the legality of rural unions. The Alessandri

administration was particularly troubled by police reports of the spread of

Marxist ideas among the rural working poor. For decades, antirevolutionary

governments had dealt with urban manifestations of revolutionary thought,

and Alessandri himself had established limits to Left-oriented social protest

during his first administration (the massacre at San Gregorio, for example).

During Alessandri’s second presidency, administration officials routinely

investigated landowner complaints regarding ‘‘agitadores’’ (urban unionists

who ‘‘stirred up’’ revolutionary sentiment) in the countryside and sought to

curtail their activities whenever possible.

∫∫

Landowners, meanwhile, also

expressed concern that not enough workers were on hand to harvest the

crops of Central Valley haciendas owing to ongoing urbanization.

∫Ω

While attempting to protect their socioeconomic power amid unioniza-

tion and calls for rural reforms, landowning alessandristas cast themselves

both as campesinos and as authentic representatives of chilenidad.

Ω≠

The

SNA, for example, demonstrated in April 1933 the importance of forging

discursive and symbolic ties to the rural worker and chilenidad by changing

the name of its journal, the Boletín de la Sociedad Nacional de Agricultura, to El

Campesino. The fact that El Campesino was a journal dedicated to the concerns

of landowners suggests that large landowners identified themselves with (or