Barr-Melej P. Reforming Chile: Cultural Politics, Nationalism, and the Rise of the Middle Class (ENG)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

132 Prose, Politics, and Patria

even as) campesinos—just ones with land titles and unmitigated power.

Middle-class intellectuals had accentuated the countryside’s chilenidad, and

landowners found personal significance in that idea, regardless of its origi-

nal intent. Thus, landowners could easily arrive at the conclusion that Marx-

ists who wanted to unionize the countryside were alien to the campo and

were anti-Chilean for seeking to disrupt time-tested rural lifeways and tradi-

tions. Reformers shared this opinion to some extent but found a place for

campesino lifeways and traditions in a populistic discourse that differed

from the status quo discourse of alessandrista landowners.

By the early 1930s, criollista stories and huaso imagery were common in the

pages of El Campesino. In a decade that saw the short-lived Socialist Republic

of 1932 and the founding of the PS the next year, some notions found in

criollismo, such as dedicated labor and tranquillity, appealed to the landown-

ing elite searching for some way to defend their political turf and justify

rural socioeconomic relations. In El Campesino, the SNA turned to criollista

short stories to make its own, interpreted political and nationalist state-

ment. Federico Gana’s ‘‘La señora,’’ a story written in 1899 that was included

in the 1916 anthology Días de campo and published in El Campesino’s April 1933

edition, describes a visit to a Central Valley hacienda where the mayordomo,

the huaso Daniel Rubio, was raised by the estate’s señora.

Ω∞

Found destitute

as a young boy, Rubio was fed, educated, and unofficially adopted by the

landowning family. Rubio never left the estate, never married, and later

assumed full care of the señora after her husband’s death. The visitor, im-

pressed by the harmony and interpersonal commitments of hacienda life,

remarks that he is touched in some profound way: ‘‘The birds sang with

happiness. The fresh morning air seemed to infuse me with liveliness, a

strange force. I thought that this happiness, which seemed to overflow with

the first rays of the sun, had come from the outstretched hand of that

man.’’

Ω≤

Gana’s huaso protagonist reflects a singular morality and unmatched

sense of responsibility considered typical of the rural experience. The SNA’s

landowners, it seems, found in ‘‘La señora’’ a defense of deference and pater-

nalism, a facet of inquilino-patrón socioeconomic relations that had contrib-

uted to rural stability (and inquilino subservience) since the colonial period.

The vision of an authentic pastoral life served the discursive needs of the

landowning class, which at that time was defending traditional rural society

amid unionization and calls for agrarian reform.

Ω≥

Oligarchs and middle-class reformers established not only a precarious

political accord in the early 1930s but also a superficial meeting of the minds

regarding what constituted lo chileno; both groups found great national and

Prose, Politics, and Patria 133

cultural value beyond the city’s edge. A 1932 editorial in the Boletín de la

Sociedad Nacional de Agricultura, for example, states that a ‘‘return to agricul-

ture today seems a unanimous aspiration. Everyone focuses their sight on

mother earth with the hope that she returns to us good times lost during

these years of universal ruin.’’ The editorial calls for a ‘‘return to the search

for the simple life.’’

Ω∂

Yet, as La chica del Crillón broke book-selling records in

the mid-1930s, the political alliance between reformist mesocrats and the

more conservative alessandristas crumbled. The rupture between reformers

and alessandrismo included a rush by both blocs to stake claims to rural

imagery. Landowners, conscious of the mesocracy’s political intentions in

the upcoming presidential election of 1938, began to criticize ‘‘urban’’ con-

ceptions of lo rural and claimed the campo as their exclusive domain. By

doing so, landowners believed their candidate, Gustavo Ross Santa María,

would be considered an authentic national persona—a true leader of the real

Chilean people, the campesinos.

In an October 1937 address over the SNA-owned radio station, a land-

owner spokesman suggested that urban intellectuals seeking to capture the

essence of rural life were participating in a somewhat bogus venture. He

stated that ‘‘for the huasos of the Cordillera [the Andes], the city man is a

gringo’’ and that ‘‘to go to the countryside with the perception of a Kodak

[camera] serves to capture only exteriors, to produce imitations.’’ Only land-

owners and rural workers, the speaker argued, really understood the campo’s

essence. The spokesman then posed a simple question: ‘‘Let us ask: does the

writer have any mission to complete in the countryside?’’

Ω∑

The comments

are insightful when placed within the context of the growing political rift

between alessandrista landowners and reformers of the urban middle class.

Though the Conservative, Liberal, and Radical parties had combined to

clinch Alessandri’s victory over Socialist Marmaduke Grove and Communist

Elías Lafertte in 1932, Radicals soon believed that Alessandri’s failure to

launch an extensive reform agenda represented a relapse of oligarchic rule

reminiscent of the Parliamentary Republic. The alessandrista Right, mean-

while, increasingly feared the possibilities of a populist candidate and his

electoral victory in the presidential elections of 1938. Aware that Radical

reformers ‘‘with a mission to complete’’ could potentially curtail landowner

power, the SNA made it clear that urban intellectuals visiting the campo (to

arouse political support for frentismo?) or merely imagining the countryside

were unwelcome gringos, a foreign species.

It must be noted that none other than Eduardo Barrios (1884–1963), a

criollista who became a landowner in the Andean foothills east of Santiago in

134 Prose, Politics, and Patria

the 1930s thanks to high-paying civil service posts and money gained from

winning two national lotteries, gave the SNA radio address in question.

Ω∏

Barrios was the most conservative criollista of the genre’s second generation,

and his political interests squared with those of the traditional landowning

class after he became a self-made and self-styled hacendado. But Barrios’s

politics were never cut and dry, as his long ties to Ibáñez attest. The former

fundo administrator was minister of education for the dictator Ibáñez in the

late 1920s as well as during Ibáñez’s elected presidential administration in

the 1950s. Barrios also headed the National Library during his long public

life. He began writing short stories in the 1920s but did not publish his most

notable novel, Gran señor y rajadiablos, until 1948. In general, it was well re-

ceived, but some reform-minded intellectuals, including Barrios’s acquain-

tance Ernesto Montenegro, were critical of the novel’s conservative over-

tones. As Montenegro recalled, ‘‘In my view, when Barrios invokes with

exaggerated fervor the virtues of a paternalistic caste, like he does in Gran

señor y rajadiablos, he has left the domains of his experience to rise to the level

of abstraction, of political philosophy.’’

Ωπ

For our purposes here, taking

Barrios into account reminds us that literary genres, by nature of their

creative dimensions, seldom exhibit rigid uniformity, as Pierre Bourdieu

suggests.

Ω∫

As the 1938 presidential election approached, conservative landowning

interests—and the alessandrista campaign in general—hoarded huaso imagery.

In October, the SNA published a special issue of El Campesino to celebrate the

association’s one-hundredth anniversary. What was normally a publication

devoted to more practical topics, such as labor and property issues, became a

public relations portfolio of the nation’s rural heritage. The huaso cowboy is

visible throughout. An article on horses and horsemanship shows huasos,

including children, in perfect command of their beasts.

ΩΩ

Others are pic-

tured sitting tall in their saddles, gazing over the rural landscape.

∞≠≠

After

thumbing through numerous pages of photos depicting hardworking and

seemingly content huasos, one comes across an article on inquilinos. The piece,

an excerpt from the book Agricultura chilena by Luis Correa Vergara, flatly

states that ‘‘the inquilino system is not as bad as many people think.’’ It goes

on to cite Claudio Gay, who favorably compared inquilinos to other fundo

laborers in the mid-nineteenth century. In short, the SNA sought to con-

vince the ever expanding reading public that huasos and other campesinos

were doing just fine, regardless of what frentistas were saying about poor

rural conditions.

The landowning class and its candidate went so far as to embrace the huaso

Prose, Politics, and Patria 135

as an unofficial campaign symbol for the election. At campaign stops, horse-

men whom the press and Ross’s political operatives called huasos—perhaps

inquilinos ‘‘invited’’ to the events by their landowners, or the landowners

themselves—often greeted the alessandrista candidate.

∞≠∞

In August, during

Ross’s final campaign swing through the southern Central Valley, some

thirty-five hundred huasos are said to have paraded in Linares in his honor.

El Diario Ilustrado reported that huasos from numerous nearby haciendas

gathered at the city’s athletic field to pay homage. The newspaper, a vo-

ciferous supporter of Ross, quoted Linares’s PL leader Nicanor Pinochet as

saying: ‘‘Here [in the countryside] we all know that the Popular Front is

the enemy of the patria.’’

∞≠≤

Pinochet construed urban space—with all its

problems, including the social question—as the FP’s domain. Moreover, in

Maule, the native land of Latorre, Ross witnessed a twenty-minute proces-

sion of huasos. El Diario Ilustrado reported that ‘‘huasos paraded behind a large

Chilean flag . . . and passing in front of the balcony where Ross was located,

the parading huasos lifted their sombreros and burst out in cries of victory.’’

∞≠≥

In this way, then, images and symbolism so typical of the criollista imagina-

tion were discursive elements of a conservative nationalism that the SNA,

alessandristas, and rossistas habitually professed during the 1930s. The un-

abashed cosmopolitanism so typical of the Parliamentary Republic’s aristoc-

racy had, over the course of a few years, given way to a nationalism espoused

by an oligarchic establishment desperate to sustain hegemony.

The FP was quick to comment on Ross’s huaso support. The newspaper

Frente Popular, reporting on Ross’s stop in Curicó, stated that pro-Ross

huasos, ‘‘sent there from neighboring fundos, assaulted the local office of the

PS, located a few meters from Curicó Station and the police station.’’ The

huasos then ‘‘defaced the house of a known frentista, which, according to his

report, belongs to Mr. Gregorio Contreras.’’

∞≠∂

Clearly, some huasos operated

under the influence of their Ross-supporting landowners, Frente Popular

indicates. A year earlier, the newspaper had called the rural lower class a

realm of ‘‘reaction’’ but inferred that overbearing and oppressive landowners

were to blame, not workers.

∞≠∑

Bellicose and apparently obedient campesinos

aside, FP intellectuals and politicians viewed huasos in a rather positive light.

With the PR on board after 1936, frentistas employed the huaso mystique and

ruralesque imagery in a populistic discourse that, among other things, in-

cluded a call for the fundamental transformation of rural social relations

and conditions.

The spectacle at the Caupolicán Theater in 1939, discussed at the begin-

ning of this chapter, points to the high value placed on campesino heritage

136 Prose, Politics, and Patria

by the FP’s intelligentsia. Another example of this tendency is a remarkable

photo of huasos on horseback with clenched fists raised over their heads,

which appeared in Frente Popular on the eve of the 1938 presidential election.

The accompanying caption reads: ‘‘Huasos who came from Province of Co-

quimbo as authentic ambassadors of the rural lower class, who proclaimed

Aguirre Cerda their candidate in the March for Democracy in La Serena

under the banner ‘Agriculturists will vote for an agriculturist.’ [Aguirre

Cerda came from a moderately successful landowning family.] Those pic-

tured [in the photo] are part of the column from the Communist Party.’’

∞≠∏

In essence, not only are the ubiquitous huasos displayed as representatives of

the rural working class, but Frente Popular (primarily a mouthpiece of the

Communist and Socialist parties) would have its readers believe that campe-

sinos were participants in frentismo’s national(ist) movement and national

political affairs.

As one would expect, moderate frentistas shied away from the notion of

revolutionary huasos. They did, however, contribute to the ruralesque rhet-

oric that surrounded Aguirre Cerda’s candidacy. Born in the village of Po-

curo near the town of Los Andes in the northern Central Valley province of

Aconcagua, Aguirre Cerda is known to have felt a certain affinity for his rural

roots. Though primarily seen by his contemporaries as the candidate of the

urban masses, Aguirre Cerda (also known as ‘‘Don Tinto,’’ a reference to his

ownership of a vineyard) drew praise for his supposedly authentic link to the

campo. A late 1938 Zig-Zag article described the son of a small landowner in

the following terms: ‘‘Don Pedro is the traditional Chilean, an archetype of

our people. He is the Chilean who loves his country. . . . Chile lifts him to tri-

umph because Chile is the people, the Popular Front; and Chile is also Don

Pedro, born in the countryside of Pocuro.’’ The edition goes on to state that

‘‘governed by him, we will feel more Chilean, more attached to our land

and mountains’’ and that he represents ‘‘the Chile . . . of the poncho, the

dark-skinned [los morenos], the rural, the hard-working, and the friend of

liberty.’’

∞≠π

With Aguirre Cerda’s victory over Ross, mesocrats not only emerged as the

dominant political force in the country but also could now fully employ the

ever expanding governmental bureaucracy to champion chilenidad and en-

courage sentiments of national/cultural authenticity brought to public at-

tention by the criollistas. Progressive nationalist representations of pastoral

life—sanctioned by the state—became ‘‘official’’ components of Chilean na-

tional identity during the early years of the FP. In 1939, the new government

Prose, Politics, and Patria 137

published a compilation of freehand drawings and descriptive passages that

essentially sanctioned the huaso as a national archetype. Written by Carlos

del Campo for the tourist bureau of the Ministry of Development, Huasos

chilenos hails the horseman as the cornerstone of society and identifies him

as typically or authentically Chilean. Written in Spanish with accompanying

English translation, Huasos chilenos includes mention of the festive rodeos,

the zamacueca, and the skilled horsemanship of huasos. The cowboy is, ac-

cording to del Campo, quite a hero: ‘‘With his wide-brimmed sombrero, his

vividly colored chamanto, high boots and clinking spurs, he is, in the midst of

our panorama, a handsome and energetic representative of the race.’’

∞≠∫

Rodeos and Zamacuecas

Ruralesque notions of lo nacional were not restricted to political discourses

and electoral struggles. By the 1930s, they were detectable in everyday cul-

tural practices, including those of the urban elite. What once was laughable

became fashionable; what was rural became national and nationalist. The

decade saw a tremendous assortment of spectacles with rural themes de-

signed to lure urban audiences. In 1930, the anniversary celebration of the

founding of San Bernardo (just south of Santiago) included cuecas danced by

participants who showed a ‘‘real mastery for the classical national dance.’’

∞≠Ω

The 1935 Independence Day celebration in Santiago’s Cousiño Park also had

a notably rural flavor: ‘‘We noticed the presence of huasos on horseback,’’ El

Diario Ilustrado reported. ‘‘This year, there was a rejuvenation of the Chilean

cueca, which is definitely banished from our aristocratic salons. We had seen

it banished . . . [and] poorly replaced by tangos, fox trots, one-steps, rumbas,

and cariocas.’’

∞∞≠

The zamacueca may not have made it into the Union Club

but nonetheless was given national importance by the conservative press.

∞∞∞

Twenty-five years earlier, El Diario Ilustrado had reported entirely different

Independence Day festivities. Among other things, the newspaper covered a

government-sponsored centennial dinner (French cuisine was on the menu)

and a symphony that played classical music atop Santa Lucía Hill in down-

town Santiago.

∞∞≤

Zamacuecas were also important in another forum in which lo rural was

celebrated: the rodeo. Large crowds of campesinos, middle-class profession-

als, and aristocrats filled midcentury rodeo arenas, cheering huasos who pa-

raded the flag and danced zamacuecas before and after performing feats of

138 Prose, Politics, and Patria

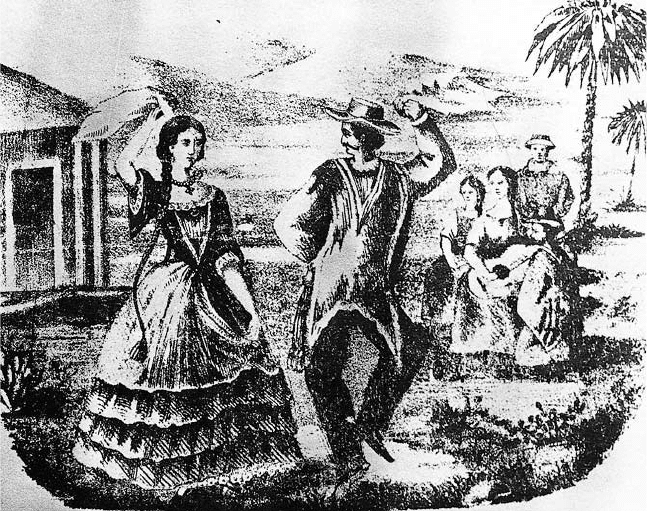

The zamacueca (or cueca), depicted in this early-twentieth-century illustration, became widely

regarded as Chile’s national folk dance during early decades of the century. Today, cuecas are

danced at public and private celebrations of all sorts and figure prominently in the festive

Independence Day celebrations each September. (Courtesy of the Consocio Periodístico, S.A.

[Copesa], and La Tercera, Santiago)

horsemanship. The travel diary of Erna Fergusson describes the pageantry of

a rodeo held in the early 1940s. The North American’s detailed account

begins with a horde of huaso horsemen, dressed in colorful patriotic attire,

anxiously waiting inside the rodeo arena, or medialuna.

∞∞≥

One by one, the

horsemen took turns chasing young steers. Fergusson notes that they were

‘‘as handsome a lot of men as one would wish to see, completely at ease with

their mounts, comfortable with each other and the onlookers.’’

∞∞∂

By the

time of Fergusson’s trip, Chilean rodeos, which began during the colonial

period as seasonal roundups of cattle from the outskirts of the haciendas,

had been transformed from a laborious duty for inquilinos into a ritual

thought to demonstrate cultural singularity and the nation’s heritage. To-

day, huaso associations throughout the country regularly sponsor rodeos,

including the remarkable Huaso Club of Arica, founded in 1968 in the once

Peruvian, nonagricultural, and arid north! But there are no inquilinos among

these contemporary huasos. Agrarian reform in the 1960s and 1970s did away

Prose, Politics, and Patria 139

with Chile’s service tenantry, leaving ‘‘huaso tradition’’ in the hands of prom-

inent families and urban professionals with small parcelas (plots) who, from

time to time, give up their cellular telephones for bridles.

The Limits of Discourse

A hallmark of early frentismo, progressive nationalism’s populistic and anti-

imperialist underpinnings certainly dovetailed with the PR’s strategies to

combat the elite’s power, further national economic development by curtail-

ing foreign capital, and mobilize the lower classes in support of the FP. But

as rural unionization expanded during the Aguirre Cerda presidency, Radi-

cals proved there were strict limits to what lower-class Chileans could do as

valued members of the patria. In late 1939 and 1940, Aguirre Cerda pleased

landowners, including the SNA, by moving against ‘‘professional agitators’’

in the countryside and suspending rural unionization, in exchange for the

former oligarchy’s support in the Congress for frentista programs.

∞∞∑

In the

press, leftists ardently condemned any suppression of rural unionization,

but the FP’s Socialists and Communists nevertheless agreed with Radicals

to suspend it. Socialists, in return, received important administrative posts,

and a congressional proposal to outlaw the PCCh was defeated.

∞∞∏

On the

surface of things, the FP parties seemed to have made a short-term conces-

sion for long-term legislative gain. However, in the case of the PR’s decision

to suspend union organizing in the countryside, we should not underesti-

mate the consequence of Radicalism’s history of anti-Marxist sentiment.

One can easily imagine Radical reformers of the early FP fearing that peons

and huasos were in danger of being corrupted by detachments of very con-

vincing rabble-rousers of revolution (Edwards Bello’s La chica del Crillón

warns of this very problem). One writer vigilant of labor organizing in the

countryside observed in 1940 that ‘‘communist agitators have shown intel-

ligence in attacking this stronghold of reaction first, for the guaso is, in

reality, the bourgeois of the masses.’’

∞∞π

As minister of the interior under Aguirre Cerda, criollista and Radical boss

Guillermo Labarca signed a circular on August 17, 1940, that directed na-

tional police to make extraordinary efforts to arrest those in the countryside

suspected of harboring or fomenting sentiments that, in his words, would

‘‘only lead to the creation of an environment of social unrest.’’ In a written

statement sent to police director Oscar Reeves Leiva, the criollista states that

revolutionary elements also cause the ‘‘formation of unnecessary and unac-

140 Prose, Politics, and Patria

ceptable hatreds that bring with them grave consequences for our patria.’’

∞∞∫

The countryside, he reasoned, should remain a tranquil place—as depicted in

his cuentos published nearly four decades earlier. As faithful Radicals, Aguirre

Cerda and Guillermo Labarca believed that state-based reform was the only

acceptable political option. The criollistas, the reader will recall, did not sanc-

tion the idea of politicized campesinos. Like the outspoken Zola, who had

vehemently defended Dreyfus in late-nineteenth-century France, Guillermo

Labarca demonstrated that his art and politics were commensurate.

∞∞Ω

In their many cuentos and novels, Guillermo Labarca and other middle-

class intellectuals of the criollista movement conveyed ideas and sentiments

with populistic intonations that were congruent to a Radical project that

was antirevolutionary and antioligarchic. Some criollistas were members of

the PR, and others were not, but collectively they participated in the mold-

ing of a new cultural and national consciousness that was considerably more

democratic than conceptions of culture and ‘‘nation’’ prevalent among the

elite of the Portalian and Parliamentary republics. While an urban reader-

ship consumed criollismo and many grew fond of the campo and its campesi-

nos, reformers in the realm of public education were also busily rethinking

and remaking Chile. They, too, profoundly shaped the cultural sphere and

professed a nationalism that was progressive and populistic as they maneu-

vered between the forces of revolution and reaction.

Gobernar es educar.

valentín letelier, La lucha por la cultura, 1895

For Culture and Country ∑

Middle-Class Reformers in Public Education

When reflecting on the education of the young Émile, Jean-Jacques Rous-

seau remarked that ‘‘plants are shaped by cultivation and men by educa-

tion. . . . We are born weak, we need strength; we are born totally unprovided,

we need aid; we are born stupid, we need judgment. Everything we do not

have at our birth and which we need when we are grown is given us by

education.’’

∞

Like the eighteenth-century philosopher whose ideas helped

shape the ideology of the French Revolution (and Latin American indepen-

dence revolutions, for that matter), middle-class Chileans associated with

the Radical Party (PR) and other reformist groups of the late nineteenth and

early twentieth centuries were astutely aware of education’s remarkable po-

tential for molding present and future generations. Many prominent teach-

ers, bureaucrats, politicians, and intellectuals shared the belief that educa-

tion was a necessary component of modernization, a linchpin of liberal

democracy, and a key to social peace across class lines. But properly executed

instruction, they held, went beyond the teaching of reading, writing, arith-

metic, history, foreign languages, physical education, or scientific knowl-

edge; it entailed carefully orchestrated programs of ideological coaching

that bestowed upon pupils concepts of Chilean singularity, national soli-

darity, and citizenship.

While reform-minded criollistas posed alternatives to elitist conceptions