Barr-Melej P. Reforming Chile: Cultural Politics, Nationalism, and the Rise of the Middle Class (ENG)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

162 For Culture and Country

In a 1920 manifesto, the Catholic association stated that reformers were

reviving church-state animosity that, to some extent, had been soothed dur-

ing the late nineteenth century. It chided the PR for believing it is ‘‘Chile’s

intellectual axis’’ and argued it ‘‘has not yet reached the cultural level of

respecting the conscience of others, making it clear that its patriotism has

been too weak for it to refrain from expressing unjust hatred against the

church.’’ On secularization of Chilean society, the association noted, ‘‘As

patriots we reject it, because we know that all of the great labors in Chile

have been done with the decisive cooperation of the church. . . . To us, the

patria without religion would not be what it is today.’’

∫∂

This statement

captures the conservative bloc’s belief that God and nation were wed. Any

notable expansion of the secular state was considered a threat to the very

underpinnings of the patria. National salvation in the face of the social

question and cultural problems, conservatives thought, had a religious solu-

tion. As the reader will recall, intellectual Juan Enrique Concha, a leading

defender of church power, argued that the ‘‘teaching of Christ, practiced by

the individual and respected and supported by the State and its laws’’ could

save Chile from disintegration.

∫∑

To the chagrin of its conservative opposition, the passage of the Law of

Obligatory Primary Instruction on August 26, 1920, which took effect exactly

six months later, forever expanded the secular state’s power in Chilean cul-

ture, while President Alessandri’s close attention to pedagogical matters

gave reformers great hope regarding cultural democratization.

∫∏

Cheering

crowds took to the streets of Santiago on August 29, including a large group

of teachers and students from local normal, primary, and secondary schools

that triumphantly marched to La Moneda.

∫π

One joyful reformer, writing in

the government’s Revista de Educación Primaria, noted in early 1921 that the

new law ‘‘has been established and has struck a hard blow to ignorance.’’ The

state’s new education policy, he goes on to state, is ‘‘in harmony with the

vigor of the race, with the fertility of our valleys, with the enormous wealth

of our soil, with the inexhaustible springs of our rugged mountains.’’

∫∫

It is certainly difficult to gauge whether or not obligatory primary educa-

tion dealt an immediate ‘‘hard blow’’ to illiteracy, given that literacy climbed

steadily during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The adult literacy

rate already had risen from 13.5 percent in 1854 to approximately 25 percent in

1885. It stood at 50 percent in 1920, 56 percent in 1930, and climbed to roughly

85 percent by 1960.

∫Ω

What these figures do not show, however, is that literacy

made a marked advance within the lower classes during the early twentieth

century, while the elite held a monopoly on literacy during much of the

For Culture and Country 163

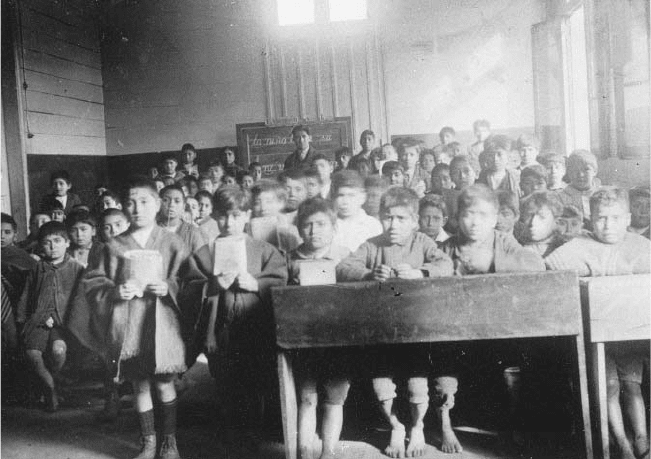

Children assembled for a photo at a public primary school, ca. 1920. The school’s location is

unknown. (Courtesy of Eduardo Devés)

nineteenth century. The law did have an instantaneous effect on matricula-

tion figures. In August 1920, there were 289,148 pupils officially enrolled in

primary schools. The number rose to 376,930 by August 1921.

Ω≠

Darío Salas,

the author of El problema nacional, served as general director of primary

instruction during this enrollment boom.

The Law of Obligatory Primary Instruction was far more effective in cities

than in rural areas, where enforcement proved difficult. The law stipulated

that all hacendados with properties larger than 2,000 hectares and valued over

500,000 pesos were required to operate, mostly at their personal expense, a

primary school if the number of elementary-age children on their land num-

bered more than twenty. Many landowners skirted this responsibility. In

1924, the Ministry of Justice and Public Instruction admitted that the new

law ‘‘has not borne the fruits that were expected’’ and asked provincial gov-

ernors, intendants, and mayors to coordinate with local carabineros in mat-

ters of enforcement.

Ω∞

Bureaucrats continued to complain about enforce-

ment problems in 1930. Juan Saavedra, the director of education of the

province of Bío-Bío, for example, wrote to the ministry in June of that year

about the fundo Santa Rosa, owned by María Gana, widow of a Mr. Dufeu. It

was a property of more than 4,000 hectares and was valued at 2 million pesos

164 For Culture and Country

and did not have a primary school. The report states that more than 100

young children went without education—a clear sign of the owner’s ‘‘lack of

interest in the well-being of the children of her inquilinos.’’

Ω≤

Other land-

owners, however, immediately complied with the law, including one Luis

Mitrovich, owner of the haciendas San Vicente and Santa Rosa in the prov-

ince of Aconcagua.

Ω≥

Such rural schools established on fundos under the Law

of Obligatory Primary Instruction were free, subject to periodic inspections

by government officials, and received a modicum of material support from

the ministry.

The extended conflict over cultural democratization in the form of obliga-

tory primary education demonstrated a division between members of social

blocs who thought about culture and ‘‘nation’’ in different ways. In public

debates, many reform-minded proponents of the measure espoused a ‘‘pro-

gressive nationalism’’ that included members of the lower classes in their

imagined national community. In response, traditionalists defended their

cultural privilege and, at times, questioned the patriotism and political mo-

tives of reformers. Despite such efforts to the contrary, cultural democrati-

zation was making great headway by the end of the Parliamentary Republic,

and obligatory primary schooling was an important element. The idea of

requiring elementary-level instruction, however, did not command all the

energy of reformers during the three decades it was debated. They also

worked to open night schools for adults and similar centers of cultural

diffusion, as did others concerned with educating the working class.

Proletarians as Pupils: Night Schooling and Popular Libraries

It was a widely shared opinion among pedagogical reformers, including

Letelier, that children were essentially dry sponges waiting to be soaked with

academic knowledge, analytic tools, and, as we shall see, ideology. Adults, on

the other hand, were rightly considered the product of personal experience,

observation, and deliberate instruction realized over the course of many

years. Although reformers understood that children were ideal subjects for

socialization and acculturation, they did not want to abandon adults to

what they considered to be the malfeasance of ignorance, which facilitated

the pernicious programs of both manipulative revolutionaries and reaction-

aries. Thus, reformers actively engaged in adult education through mostly

unofficial channels during the Parliamentary Republic as part of their cul-

tural political project. It is important to stress here that Radicals were not

For Culture and Country 165

alone on this crusade. Recabarren, the founder of the Socialist Workers

Party, was an outspoken supporter of education for both children and

adults of the working class, and unions and federations, often with the assis-

tance of the Chilean Federation of Students, or FECh, formed their own

small schools. Indeed, working-class organizations, mutual aid societies,

and other groups initiated important literacy programs among workers.

Ω∂

The idea of adult education for workers was first proposed in an official

setting by reformers at the National Pedagogical Congress in 1889. In atten-

dance were the major education figures of the era, including Dr. Federico

Puga, minister of justice and public instruction for President Balmaceda.

Coupled with a resolution that called for obligatory primary education, the

pedagogical congress endorsed the idea of state-run adult night schools with

the same basic curricular structure as public primary schools. It was sug-

gested, moreover, that such adult schools could work in conjunction with

working-class organizations to spur matriculation and, if enrollments re-

mained low, prizes and other incentives could be offered to lure students.

Ω∑

As was the case with required elementary instruction, night schooling for

working adults did not materialize in the short term despite the minister’s

direct participation in the pedagogical congress. Frustrated but not de-

feated, many reformers took night schooling into their own hands. The

absence of obligatory elementary instruction before 1920 and the relative

exclusivity of the liceos motivated reformers to find alternate means of edu-

cating the masses. In 1895, La Lei called on all liberals of good conscience to

join its campaign for adult night schools for members of the working class,

the ‘‘only solid base for political power and all civilizing and progressive

projects.’’ The newspaper also declared, ‘‘The slogan on our glorious flag

should be ‘Work for Popular Instruction.’ ’’

Ω∏

With little interest shown by

government leaders regarding adult education, the founding of private

night schools became a common occurrence. Radicals proved especially suc-

cessful in this cultural endeavor.

On an autumn day in 1907, the Radical Assembly of Nuñoa (a middle-class

barrio of Santiago) met to discuss important national issues. Education was

on the agenda, and talk soon gravitated to the importance of adult night

schools. In the midst of the exchange, one member suggested that, given the

state’s indolence, the assembly should establish a night school of its own.

Strongly enthused by the suggestion, assembly members immediately orga-

nized a collection drive at the local Radical Club, where party members often

met to socialize, dine, and imbibe con gusto. The first classes at the Radi-

cal Assembly’s adult school—presumably taught by party volunteers—were

166 For Culture and Country

held at the Radical Club that same night.

Ωπ

In light of the fact that Nuñoa

had no working-class neighborhoods or, for that matter, an industrial capac-

ity, Radicals most likely found it difficult to recruit prospective students,

though there were some rural workers in the surrounding area (given the

barrio’s location on the then outskirts of the capital). While Radicals taught

adults in Nuñoa, the University of Chile and the AEN offered special courses

and conferences for workers at night and on weekends. With strong support

from the university’s rector, Valentín Letelier, the University Extension pro-

gram began in 1907 and soon merged with the AEN’s program of ‘‘popular

conferences,’’ which was established that same year under the direction of

Amanda Labarca Hubertson, renowned educator, feminist, AEN member,

Radical, and wife of the criollista Guillermo Labarca Hubertson. The exten-

sion’s corps of teachers was large, and a great many conferences were offered

during the mid- and late Parliamentary Republic.

Ω∫

In 1911, the University Extension, in conjunction with the AEN, offered

instruction in five areas—Chilean history, civic education, the ‘‘sociability of

workers,’’ domestic economy, and industrial education. Instruction took

place at various locales established by working-class organizations, such the

La Unión Artisan Society and the La Universal Society, and was imparted by

teachers who ‘‘have contributed in the most noble and exalted way to the

culture and the enhancement of the patria.’’ As Amanda Labarca described,

the AEN enthusiastically assisted the extension ‘‘as a means to expand and

carry through our action in the bosom of the working-class community,

creating closer ties between it and professors, and to give an exclusively su-

perior character to the courses and conferences of the University of Chile.’’

ΩΩ

Among the courses offered in 1912 were ‘‘Economic Patriotism’’ taught by

Alberto Edwards (a Liberal chieftain); ‘‘Theater as an Educational Institu-

tion’’ by Víctor Domingo Silva (author and Radical); ‘‘Chilean Life on the

Nitrate Pampa’’ by the criollista Baldomero Lillo; ‘‘Nationalist Politics’’ by

Guillermo Subercaseaux; ‘‘The New Phase of Science in Chilean Teaching

and Education’’ by Encina; and ‘‘Socioeconomics’’ by Aguirre Cerda.

∞≠≠

The

total number of conferences organized by the extension in Santiago during

the middle and later years of the Parliamentary Republic is very impressive,

as are attendance figures. Between October 1907 and January 1917, there were

178 conferences (regrettably, no attendance figures are available for those

years). From 1917 through 1920, thirty-four conferences reportedly drew

31,050 people, while during the years 1921–25 another thirty-six conferences

recorded a total audience of 36,750. Thus, according to figures compiled by

For Culture and Country 167

the AEN, the average University Extension conference between 1917 and 1925

drew just under 1,000 people.

∞≠∞

As the Parliamentary Republic’s demise drew nearer, private adult schools

continued to function alongside the University Extension.

∞≠≤

In July 1918, the

Francisco Bilbao Center, an organization of teachers in the city of Los An-

geles, successfully petitioned the Ministry of Justice and Public Instruction

for use of a primary school for adult instruction at night. The teachers asked

for permission on the grounds that they realized the ‘‘ignorant state in

which the working classes live’’ and desired to contribute to the ‘‘progress of

our masses.’’ The center, moreover, pledged to install electrical lighting at

the school at no cost to the government. Minister Aguirre Cerda gave final

approval to the plan.

∞≠≥

A year later, the Third Company of Firemen of

Santiago declared its intention to open a night school on the premises of the

Alberto Reyes Primary School in the name of ‘‘justice and liberty.’’ The

ministry’s director of primary instruction, Darío Salas, endorsed the idea,

which was later authorized by Aguirre Cerda.

∞≠∂

Along with the aforemen-

tioned School of Workers established by Pedro Bannen at the turn of the

century, such privately operated schools complemented the pedagogical

mission reformers assigned as their own.

Privately organized night schools were joined by state-operated night

schools during Alessandri’s first administration. By 1936, forty-three public

night schools around the country maintained an enrollment of 2,857, while

eighty-eight private establishments boasted a total of 5,687 students.

∞≠∑

In

the large scheme of Chilean education, the number of night schools and

their enrollments were but minuscule portions of the country’s pedagogical

complex. This does not mean, however, that night schooling was irrelevant.

The University Extension and the AEN did not operate schools but nonethe-

less offered courses and conferences that served a similar pedagogical role

during the later years of the Parliamentary Republic (such events were not

officially sanctioned by the ministry). Together with the University Exten-

sion and AEN, night schools taught literacy skills and basic knowledge to

many workers who, in the nineteenth century, would not have been offered

the promise of education. Reformers, especially Radicals, were leaders in this

area.

Assisting night school teachers in their cultural project were the founders

and operators of ‘‘popular libraries,’’ which generally catered to the margin-

ally literate members of the working class. Although no official count of

popular libraries was undertaken, the number most likely remained small

168 For Culture and Country

during the Parliamentary Republic.

∞≠∏

One such library was the Santa Lucía

popular library, opened by Onofre Herrera Labbé in 1906. This downtown

Santiago site, which was personally funded and staffed by Herrera, operated

from 8 to 10 p.m. and averaged about fifteen readers per night. In 1908, Santa

Lucía accommodated 3,327 readers (including returning users), was open 223

days, and boasted a total of 5,000 volumes. No fees were required. Herrera’s

devotion to after-hours education drew strong praise from the reformist

press: ‘‘Among the gold medallions they are stamping out in La Moneda for

the upcoming centennial celebration, one should be destined for this self-

sacrificing educator and public servant.’’

∞≠π

To those like Salas and Alessandri who fought for obligatory primary

education, or members of Nuñoa’s Radical Assembly who surrendered their

evenings to teach adults, or the operator of the Santa Lucía popular library,

cultural democratization was a necessary factor in the creation of an inclu-

sive democracy and interclass cohesion in a modernizing society. The diffu-

sion of literacy and basic knowledge, they believed, served to level Chile’s

cultural playing field and create a stronger nation—a nation that included

the once dismissed lower classes. Thus, reformers in the pedagogical sphere,

much like the criollistas in literary culture, articulated a cultural politics that

redefined the parameters of culture and ‘‘nation’’ by eschewing traditionalist

constructions of both that pervaded society during the Portalian and Parlia-

mentary republics. This criollo Kulturkampf of the late nineteenth and early

twentieth centuries saw conservatives defend the Catholic Church’s cultural

role in society and once again underscored the lingering discord between

conservatives and liberals in Chilean political culture. Liberal Party mem-

bers tended to side with Radicals on matters of cultural democratization but

were, for the most part, quiet partners (Alessandri was the most important

exception). Radical bureaucrats, politicians, intellectuals, and teachers led

the protracted effort that ultimately scored major gains in public policy.

These gains may be seen not only as pedagogical and cultural advances but

also as political ones. That is to say, middle-class reformers benefited di-

rectly in terms of their class’s political power from the state bureaucracy’s

amplification, which, of course, accompanied the greater reach of public

instruction.

It is more than reasonable to assert that parlamentarista oligarchs generally

displayed little interest in domestic cultural matters, although Conserva-

tives vociferously fought to protect the Catholic Church’s customary cul-

tural domain. Radicals became leading figures at the University of Chile and

controlled its Public Instruction Council, which oversaw public schooling at

For Culture and Country 169

the secondary level. Outside the government, both the AEN and the SNP

(founded in 1909) were laden with PR members. Some correligionarios, such as

Salas, Aguirre Cerda, and Guillermo Labarca, were members of both organi-

zations.

∞≠∫

Leftist leaders, who worked within their mutual aid societies and

syndicates to spread literacy, were absent from top posts in the pedagogical

establishment and key pedagogical associations during most of the Parlia-

mentary Republic. It was not until the 1920s that leftist educators formed

significant unions, such as the General Association of Teachers (Asociación

General de Profesores, or AGP), while others joined the SNP.

Parliamentary-era reformers not only used their considerable influence

within the pedagogical complex to pursue cultural democratization but also

moved to infuse nationalist teachings into the official curriculum. National-

ism, they believed, would neutralize revolutionary ideas, restrain the forces

of reaction, and perpetuate Chile’s singular Latin American democracy. At

the liceo level, the Radical-dominated Public Instruction Council made the fi-

nal decisions regarding course offerings and guidelines and used this power,

at the behest of the AEN and other interests, to instate ‘‘civic education’’—a

course on citizenship with decidedly nationalist overtones—officially as a

core subject in 1912. What followed was a slew of decrees and protocols

governing nationalist instruction in the classroom that culminated with the

so-called Plan de Chilenidad (Chileanness Plan), which was inaugurated in

1941 by the FP government of Aguirre Cerda.

This page intentionally left blank

Debemos recordar que la base angular de las primeras

nacionalidades del mundo ha estado en la escuela.

La Nación, July 24, 1920

Teaching the ‘‘Nation’’ ∏

When middle-class reformers of the Parliamentary Republic argued in favor

of obligatory primary instruction, they enveloped their appeals in the recog-

nizable idiom of nationalism. For more than three decades, members of

the National Education Association (AEN), Darío Salas, Arturo Alessandri

Palma, and others defended cultural democratization on the grounds of

promoting national and racial fortitude. They imagined a Chile in which

culture, in the pedagogical sense of the term, would somehow counteract

modernization’s centrifugal social forces. But reformers were convinced that

nationalism was more than a discursive weapon to be wielded on the bat-

tlefield of cultural politics. Like culture, nationalism was viewed by many as

a social mortar—an ideological link between Chileans who may otherwise

have shared little in common.

As early industrialization and the growing export sector rapidly diversified

the country’s socioeconomic landscape, revolutionary ideas made headway

in the cities as the social question intensified and the state proved that

repression remained a political option. In response to the changing condi-

tions around them, reform-minded mesocrats called for the incorporation

of nationalist (or what often was referred to, in that era, as ‘‘patriotic’’)

teachings into the required curriculum. Public schooling, they believed, not

only fought the plague of ignorance to ensure democracy, order, and prog-

ress but also was a cultural instrument capable of inculcating children of

diverse socioeconomic backgrounds with notions of national solidarity and