Biermann Ch. Handbook of Pulping and Papermaking

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

514

24.

OPTICAL PROPERTIES OF PAPER

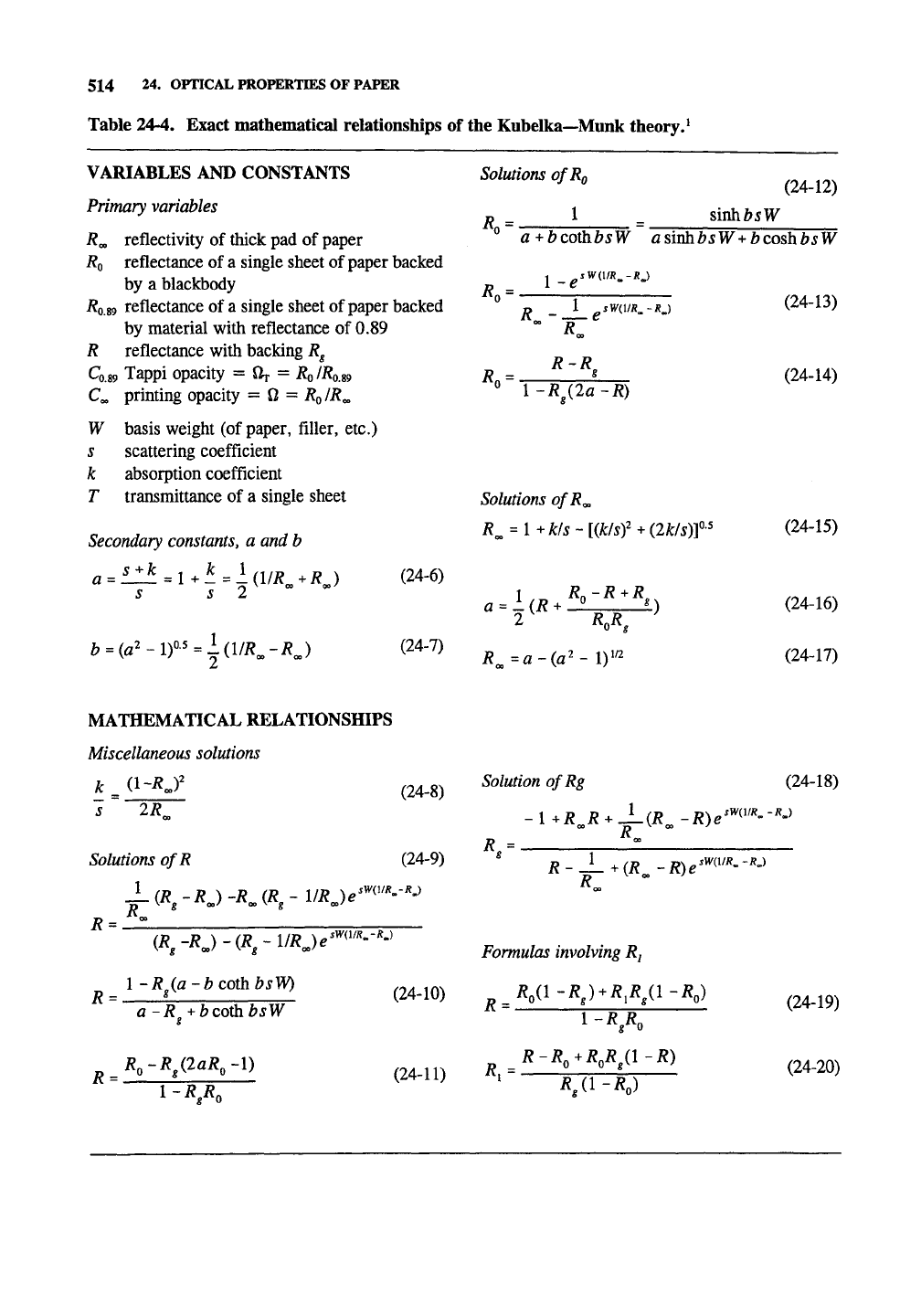

Table 24-4. Exact mathematical relationships

of

the Kubelka—Mmik theory.^

VARIABLES AND CONSTANTS

Primary variables

R^

reflectivity

of

thick pad

of

paper

RQ

reflectance

of

a single sheet

of

paper backed

by

a

blackbody

i?o.89 reflectance

of

a single sheet

of

paper backed

by material with reflectance

of

0.89

R reflectance with backing

Rg

Q.89 Tappi opacity

= Or =

-^0/^0.89

C«,

printing opacity

= Q =

RQ

//?„

W basis weight

(of

paper, filler,

etc.)

s scattering coefficient

k absorption coefficient

T transmittance

of a

single sheet

Secondary

constants,

a

and

b

a =

— =

l^!i=^l(im^R)

s

s 2 ^ ^

b

=

(a'-ir

=

^(VR^-RJ

(24-6)

(24-7)

Solutions

O/RQ

(24-12)

R.

1

sivihbsW

R,

® a+bcoihbsW asmhbsW

+

bcoshbsW

«" l-R(2a-R)

Solutions

ofR^

R^

=

l+k/s-[(k/sf

+

i2k/s)f-^

a^iiR.^^Z^l^)

R^^a-ia^-iy

(24-13)

(24-14)

(24-15)

(24-16)

(24-17)

MATHEMATICAL RELATIONSHIPS

Miscellaneous solutions

s

2R_

(24-8)

Solutions

ofR

(24-9)

J?

J.(R^-RJ-R^(R^-l/RJe

sW(VR^-RJ

R

=

(Rg-RJ-iRg-l/RJe

1

-R^(a-bcoihbsW)

a-Rg+bco±bsW

sWiVR^-RJ

R,-RaaR^-l)

!-/?/„

(24-11)

Solution

ofRg (24-18)

R^

1^R^R^±(R^-R)e''''''''-'''

R-±^(R^-R)e'''''^'^-'''

R_

Formulas involving

R,

(24-10)

^ R,il-R^)^R,R^il-R,)

l-R,Ro

R-R,*R,R^(l-R)

/?,=.

RA^-Ro)

(24-19)

(24-20)

APPENDIX 515

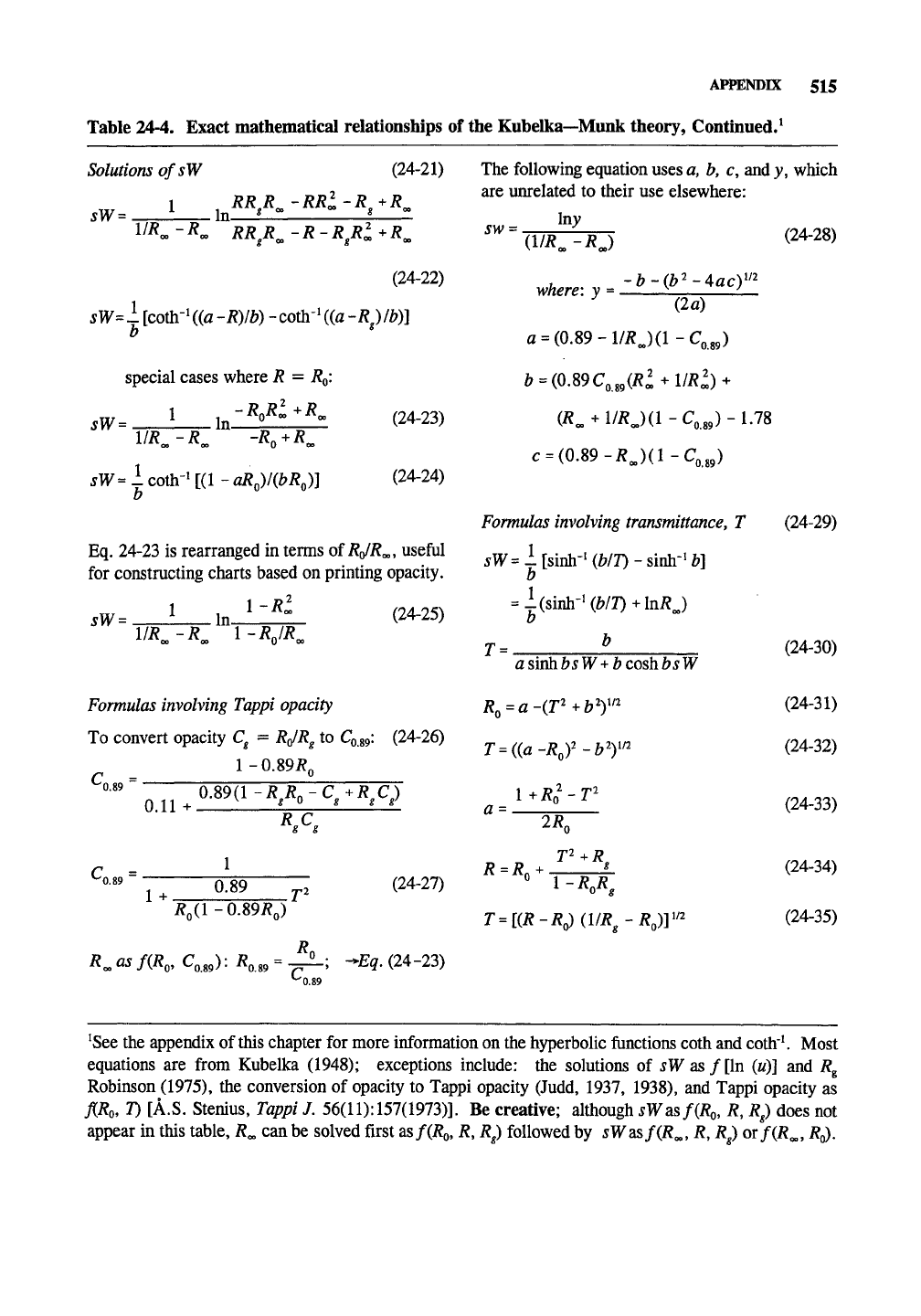

Table 24-4. Exact mathematical relationships of the Kubelka—Munk theory, Continued.^

Solutions

ofsW

(24-21)

sW--

1 RRR-RRl-R^+R„

In

l/^oo -^oo RRR^ -R-RRl

+

R^

(24-22)

sW= 1

[coth-'

((a

-R)lb) -

coihr'

{{a

-R)

/b)]

b *

special cases where R =

RQ.

1 -R.RI+R^

sW= i In—2.J: 1

IIR^-R^ -Ro^R^

(24-23)

OO 00

sW=-

coth-' [(1 - aR^)/(bR^)] (24-24)

b

Eq. 24-23 is rearranged in terms ofRo/Ro., useful

for constructing charts based on printing opacity.

sW=

I

In-

1-R:

!//?„-/?„ 1-V^„

(24-25)

Formulas involving

Tappi opacity

To convert opacity C^ = RJR^ to Co.g,: (24-26)

1 - 0.89i?„

0.11 +

"'•'' , . 0-89 ^

(24-27)

/f„(l-0.897?„)

/f„

«„ fli /(/?„, C„3,): it„^ = » ;

->Eq.

(24-23)

'-'0.89

The following equation uses

a,

b, c, and y, which

are unrelated to their use elsewhere:

sw-

lay

(IIR^-RJ

(24-28)

where:

y

••

-b-(b^-4acy'^

(2a)

fl

=

(0.89-l/ifJ(l-C„„)

b

=

(0.&9C,^{Rl^l/Rl)*

iR„ *

l/RJH-C,

J-IJ8

c

=

(0.89-RJ(l-C,J

Formulas involving

transmittance,

T (24-29)

sW=-

[sinh-'

iJblT)

- sinh"'

b]

b

= -(sinh-'(W7)

b

T - ^

^In^J

asiviibsW+b

coshbsW

R^

=

a-(T^+by

T^iia-R.y-b'y

l+Ro-T"^

0 =

2«o

i?=/?„ + L

r=[(/?-i?j

(1//?-

R.)]'"

(24-30)

(24-31)

(24-32)

(24-33)

(24-34)

(24-35)

^See the appendix of

this

chapter for more information on the hyperbolic functions coth and coth ^ Most

equations are from Kubelka (1948); exceptions include: the solutions of sW as /[In (u)] and R^

Robinson (1975), the conversion of opacity to Tappi opacity (Judd, 1937, 1938), and Tappi opacity as

J{Ro,

T) [A.S. Stenius, Tappi J.

56(11):

157(1973)].

Be creative; although sWd&fiR^, R,

R^)

does not

appear in this table, R^ can be solved first as/(i?o, ^, R) followed by sWzs>f{R^, R,

R^)

or/(/?«.,

RQ),

25

WOOD AND FIBER-GROWTH AND ANATOMY

25.1 INTRODUCTION

It is interesting to detail the development of

the entire tree, or woody plants in general, but this

information is of little use to the practicing pulp

and paper scientist. Unfortunately, the terms to

describe various plant tissues are somewhat arbi-

trary in this limited context; nevertheless, the

features of cell types can be used to distinguish

various species without the need to understand the

entire woody plant as a single organism.

This chapter presents an overview of the

anatomy of the wood of temperate softwoods and

hardwoods. The growth characteristics of tropical

species are somewhat different, especially in

regard to growth rings, and a few examples are

included as examples of this vast resource. Most

tropical woods are hardwoods, but a few soft-

woods are commercially important. Softwoods are

"designed" to resist the drought of winter where

water exists as ice and is not available.

Detailed anatomies of softwoods, hardwoods,

and some nonwood fiber sources are each consid-

ered in their own separate chapters. An overview

of

the

growth of wood is considered in this chapter

to give some context to wood anatomy. The

anatomy of various woods is important for several

reasons. For example, the characteristics of

papermaking fibers depend much upon their

anatomy. The pulping characteristics of various

fiber sources are dependent upon their species and

growing conditions.

One should review the fundamental concepts

presented in Chapter 2 if the terminology is

unclear in this chapter; Chapter 2 also has tables

of wood properties and chemical compositions.

Flat or plain sawn wood has a tangential

surface as the widest surface. Quartersawn boards

have a radial surface as the widest surface.

Letters are often used to indicate which plane of

the wood to observe to see a particular feature

including x for cross sectional, r for radial, and t

for tangential surfaces. Some features are ob-

served in individual fibers.

Traditionally wood has been used locally in

manufacturing processes even if the final products

have been transported some distance. More and

more, however, wood is being bought and sold on

the international market as local supplies dwindle

in many locations. Because of this trend, much

information on global supply and properties of

many internationally important woods is included

in this chapter. As wood becomes a more valu-

able material, its properties become even more

important. Wood quality and the manipulation of

wood quality are becoming increasingly important.

Woody

plants

There are over 500 species of softwood and

over 12,000 species of hardwoods (dicotyledons,

plants containing seeds with two leaves, that are

woody) worldwide. In the U.S. there are about 30

softwood and 50 hardwood species of commercial

importance. This number is increasing as wood

becomes in higher demand. For example, some

Populus species were not used commercially until

it was realized that they had good papermaking

qualities. Even red gum, Liquidambar styraciflua,

was considered to be a weed tree before 1900 until

methods were developed to properly kiln dry it.

About two—thirds of the commercial species used

for lumber have appreciable use in pulp and paper,

but others are also considered in this chapter as

common commercial species which may enter the

pulp mill.

All woody plants are perennial, i.e., live for

a number of

years.

They have stems consisting of

xylem and phloem tissues that conduct water and

nutrients. The xylem is lignified and constitutes

the wood. Their stems live and thicken by grow-

ing outward from the cambium each year. Al-

though most paper has more softwood fiber than

hardwood fiber, the anatomy and number of

hardwoods often make them more difficult to

identify than softwood. Woody plants can also be

classified as trees, shrubs, or liana (climbing

vines).

Dendrology is the study of woody plants.

Some herbaceous (nonwoody) plants (such as

cereal straws and bagasse) are important sources

of fiber for paper products in various countries.

516

INTRODUCTION 517

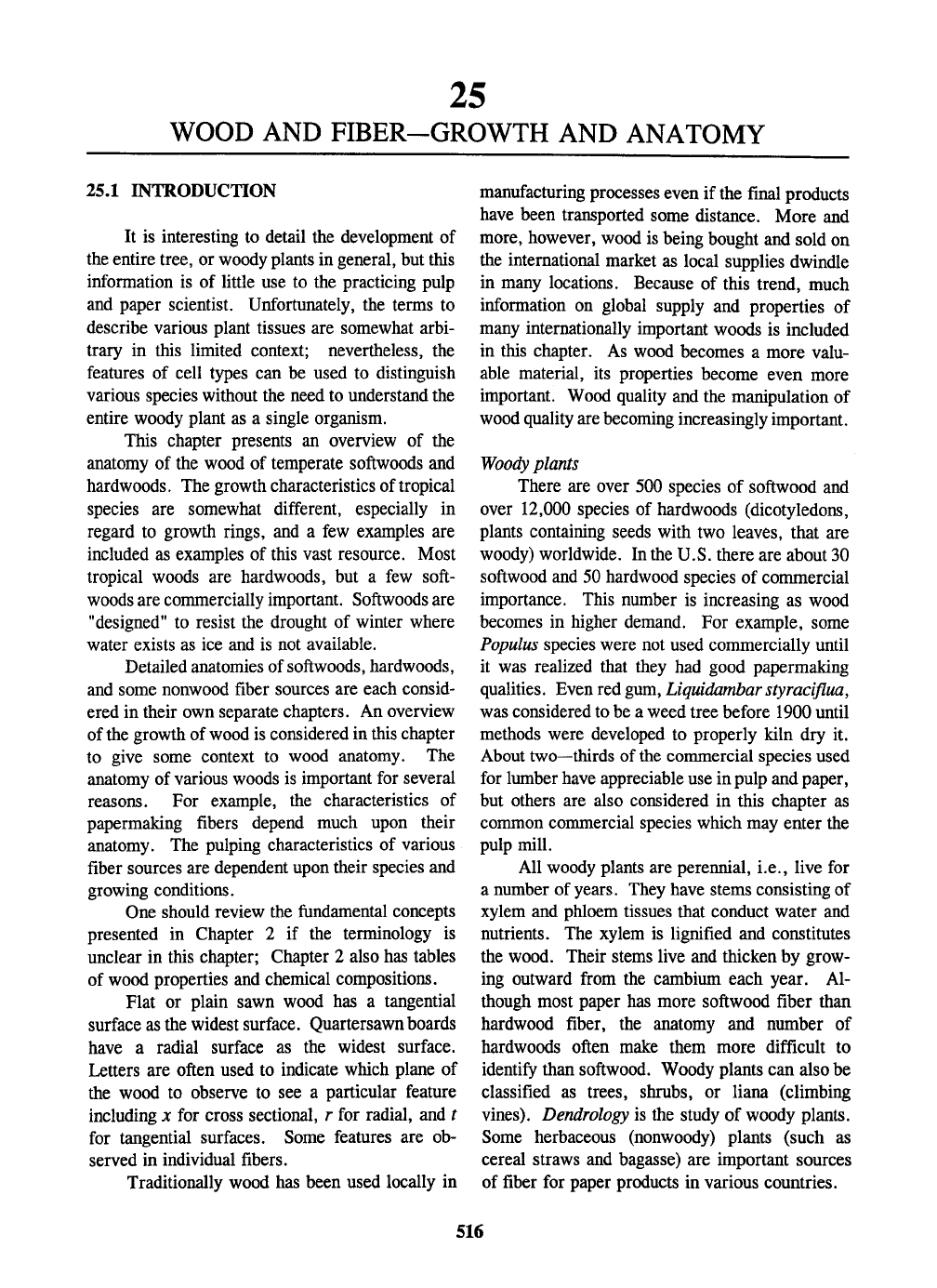

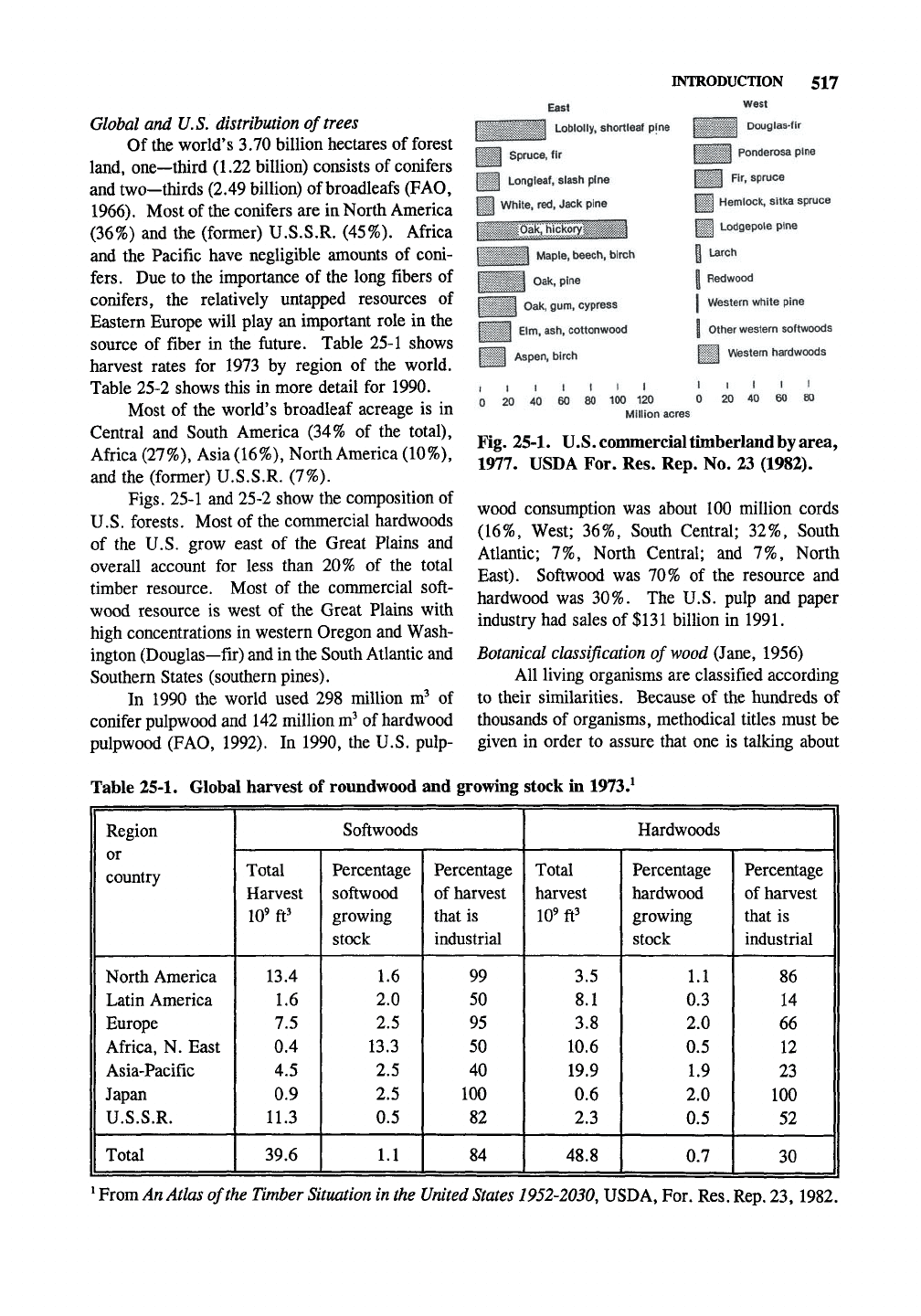

Global and U.S. distribution of trees

Of the world's 3.70 billion hectares of forest

land, one—third (1.22 billion) consists of conifers

and two—thirds (2.49 billion) of broadleafs (FAO,

1966).

Most of the conifers are in North America

(36%) and the (former) U.S.S.R. (45%). Africa

and the Pacific have negligible amounts of coni-

fers.

Due to the importance of the long fibers of

conifers, the relatively untapped resources of

Eastern Europe will play an important role in the

source of fiber in the future. Table 25-1 shows

harvest rates for 1973 by region of the world.

Table 25-2 shows this in more detail for 1990.

Most of the world's broadleaf acreage is in

Central and South America (34% of the total),

Africa (27%), Asia (16%), North America (10%),

and the (former) U.S.S.R. (7%).

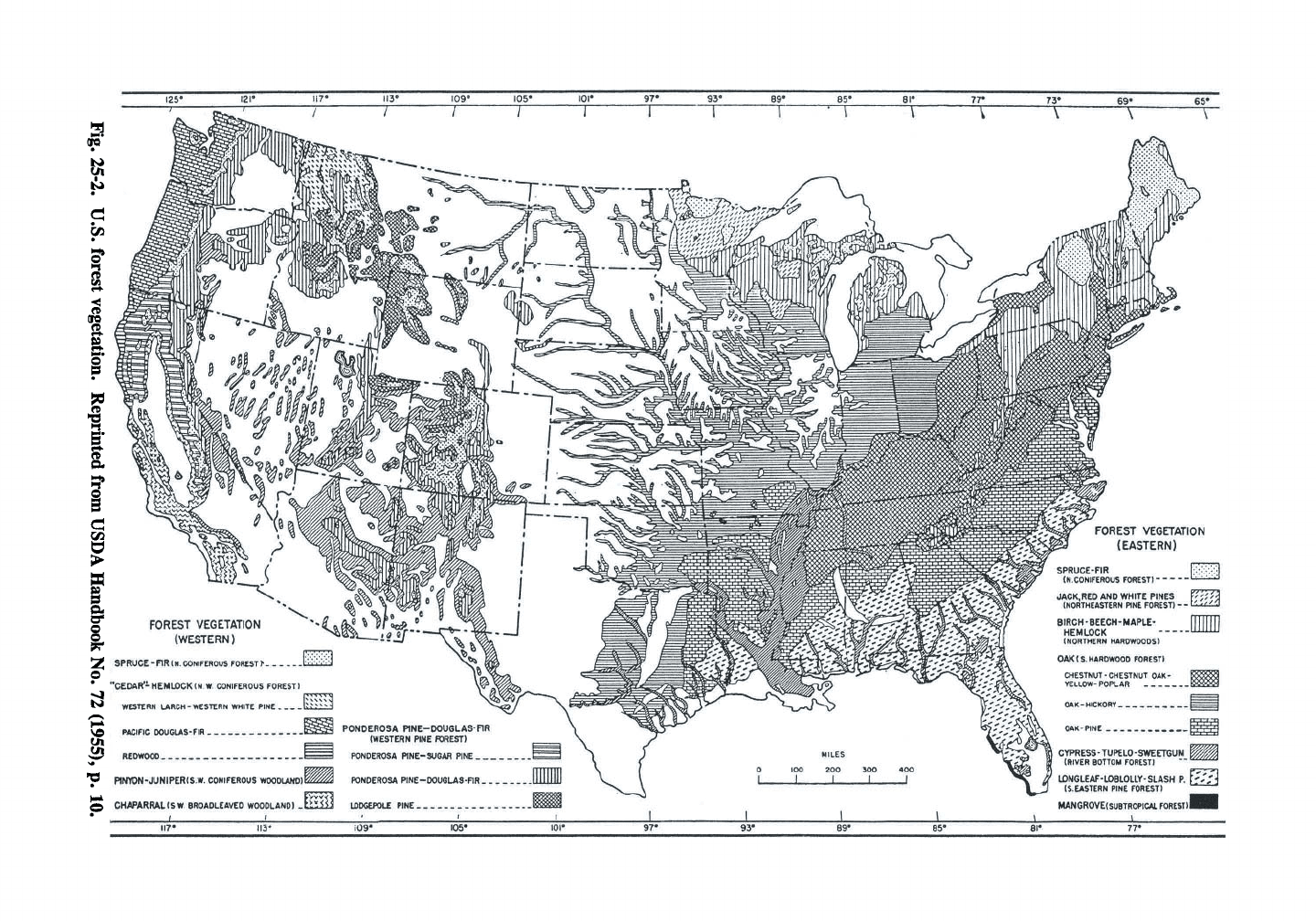

Figs.

25-1 and 25-2 show the composition of

U.S.

forests. Most of the commercial hardwoods

of the U.S. grow east of the Great Plains and

overall account for less than 20% of the total

timber resource. Most of the commercial soft-

wood resource is west of the Great Plains with

high concentrations in western Oregon and Wash-

ington (Douglas—fir) and in the South Atlantic and

Southern States (southern pines).

In 1990 the world used 298 million m^ of

conifer pulpwood and 142 million

m^

of hardwood

pulpwood (FAO, 1992). In 1990, the U.S. pulp-

West

rjf^<^\ S^ Loblolly, shortleaf pine [^yfvg^ Douglas-fir

Y^M Spruce, fir

[ni Longleaf. slash pine

Fl White, red, Jack pine

rr>sEy.

n!j^ ponderosa pine

\f^'t\

Fir, spruce

PI Hemlock, sItka spmce

pi Lodgepole pine

I Urch

I Redwood

I Western white pine

I Other western softwoods

P2 Western hardwoods

till

20 40 60 80

I Maple, t>eech, birch

\^t:^ oak, pine

Oak, gum, cypress

Elm,

ash, cottonwood

Y^'^l Aspen, birch

I I I I t I I I

0 20 40 60 80 100 120 0

Million acres

Fig. 25-1. U.S.coimnercialtimberlandbyarea,

1977. USDA For. Res. Rep. No. 23 (1982).

wood consumption was about 100 million cords

(16%,

West; 36%, South Central; 32%, South

Atlantic; 7%, North Central; and 7%, North

East).

Softwood was 70% of the resource and

hardwood was 30%. The U.S. pulp and paper

industry had sales of

$131

billion in 1991.

Botanical

classification

of

wood

(Jane, 1956)

All living organisms are classified according

to their similarities. Because of the hundreds of

thousands of organisms, methodical titles must be

given in order to assure that one is talking about

Table 25-1. Global harvest of roundwood and growing stock in 1973.^

Region

or

country

North America

Latin America

Europe

Africa, N. East

Asia-Pacific

Japan

1

U.S.S.R.

Total

Softwoods

Total

Harvest

10'ft'

13.4

1.6

7.5

0.4

4.5

0.9

11.3

39.6

Percentage

softwood

growing

stock

1.6

2.0

2.5

13.3

2.5

2.5

0.5

1.1

Percentage

of harvest

that is

industrial

99

50

95

50

40

100

82

84

Hardwoods

Total

harvest

10'ft'

3.5

8.1

3.8

10.6

19.9

0.6

2.3

48.8

Percentage

hardwood

growing

stock

1.1

0.3

2.0

0.5

1.9

2.0

0.5

0.7

Percentage

of harvest

that is

industrial

86

14

66

12

23

100

52

1

30

1

^

From An Atlas of the Timber

Situation

in the

United States

1952-2030,

USDA, For. Res. Rep, 23, 1982.

518 25. WOOD AND FIBER--GROWTH AND ANATOMY

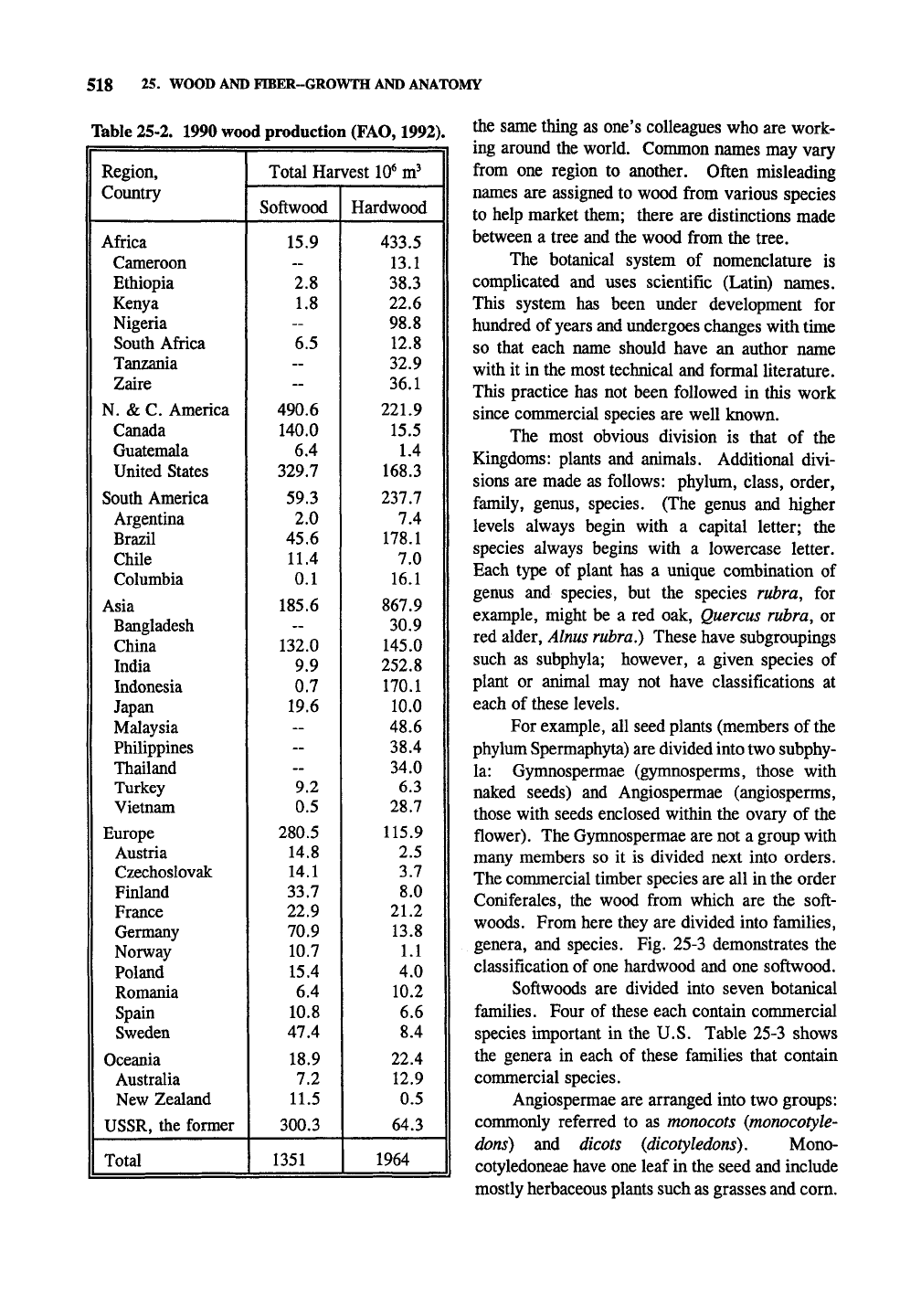

Table 25-2. 1990 wood production (FAO, 1992).

Region,

Country

Africa

Cameroon

Ethiopia

Kenya

Nigeria

South Africa

Tanzania

Zaire

N.

& C. America

Canada

Guatemala

United States

South America

Argentina

Brazil

Chile

Columbia

Asia

Bangladesh

China

India

Indonesia '

Japan

Malaysia

Philippines '

Thailand

Turkey

Vietnam

Europe

Austria

Czechoslovak

Finland

France

Germany

Norway

Poland

Romania

Spain

Sweden

Oceania

Australia

New Zealand

1 USSR, the former

I Total

Total Harvest

10^

m^

||

Softwood

15.9

""

2.8

1.8

-

6.5

~

-

490.6

140.0

6.4

329.7

59.3

2.0 '

45.6

11.4

0.1

185.6 1

1

132.0

9.9

0.7

19.6

-

-

—

9.2

0.5

280.5

14.8

14.1

33.7

22.9

70.9

10.7

15.4

6.4

10.8

47.4

18.9

7.2

11.5

300.3

1 1351

Hardwood [|

433.5

13.1

38.3

22.6

98.8

12.8

32.9

36.1

221.9

15.5

1.4

168.3

237.7

7.4

178.1

7.0

16.1

867.9

30,9

145.0

252.8

170.1

10.0

48.6

38.4

34.0

6.3

28.7

115.9

2.5

3.7

8.0

21.2

13.8

1.1

4.0

10.2

6.6

8.4

22.4

12.9

0.5

64.3

1964

the same thing as one's colleagues who are work-

ing around the world. Common names may vary

from one region to another. Often misleading

names are assigned to wood from various species

to help market them; there are distinctions made

between a tree and the wood from the tree.

The botanical system of nomenclature is

complicated and uses scientific (Latin) names.

This system has been under development for

hundred of

years

and undergoes changes with time

so that each name should have an author name

with it in the most technical and formal literature.

This practice has not been followed in this work

since commercial species are well known.

The most obvious division is that of the

Kingdoms: plants and animals. Additional divi-

sions are made as follows: phylum, class, order,

family, genus, species. (The genus and higher

levels always begin with a capital letter; the

species always begins with a lowercase letter.

Each type of plant has a unique combination of

genus and species, but the species rubra, for

example, might be a red oak, Quercus rubra, or

red alder,

Alnus

rubra.) These have subgroupings

such as subphyla; however, a given species of

plant or animal may not have classifications at

each of these levels.

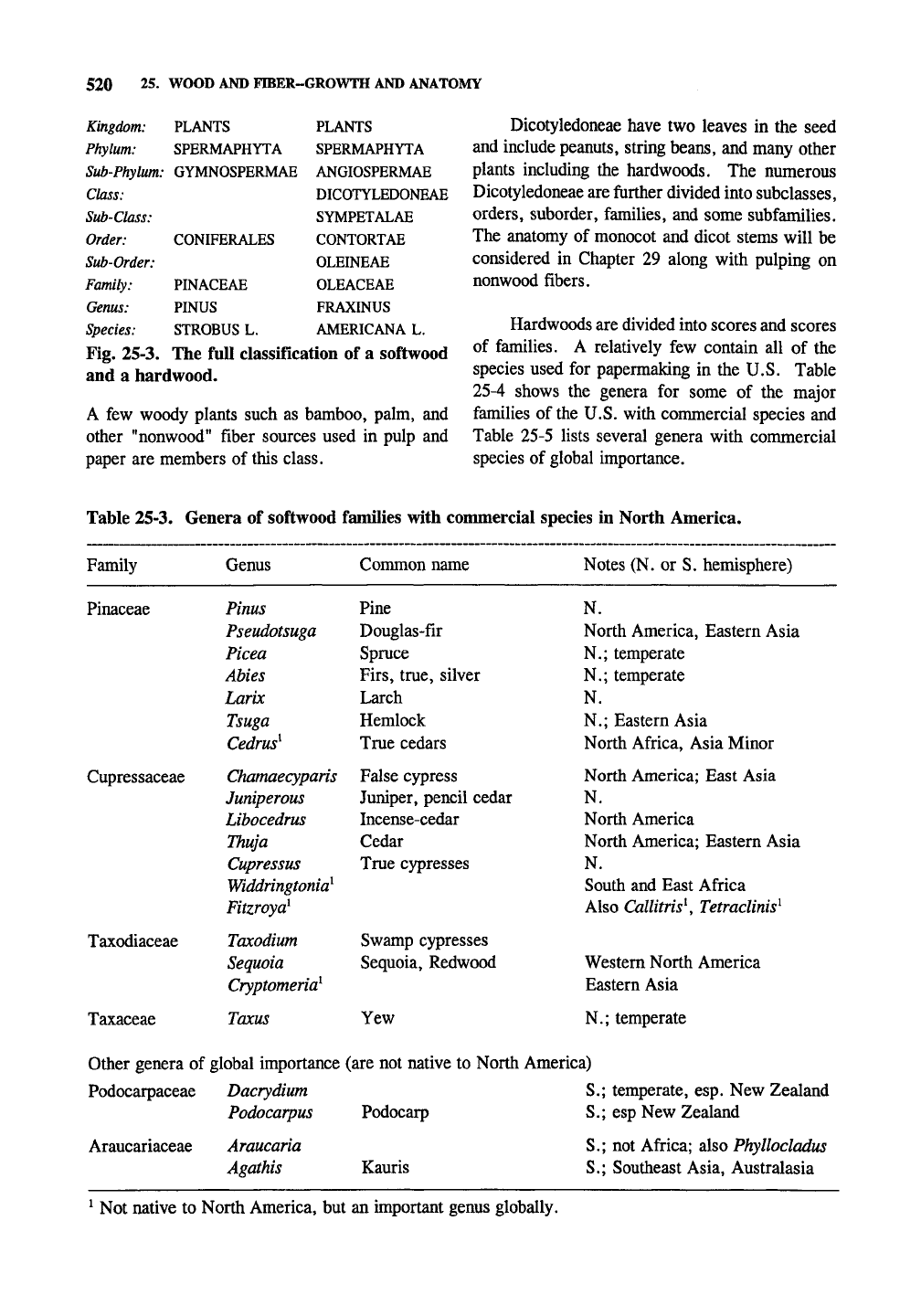

For example, all seed plants (members of

the

phylum Spermaphyta) are divided

into

two subphy-

la:

Gymnospermae (gymnosperms, those with

naked seeds) and Angiospermae (angiosperms,

those with seeds enclosed within the ovary of the

flower). The Gymnospermae are not a group with

many members so it is divided next into orders.

The commercial timber species are all in the order

Coniferales, the wood from which are the soft-

woods. From here they are divided into families,

genera, and species. Fig. 25-3 demonstrates the

classification of one hardwood and one softwood.

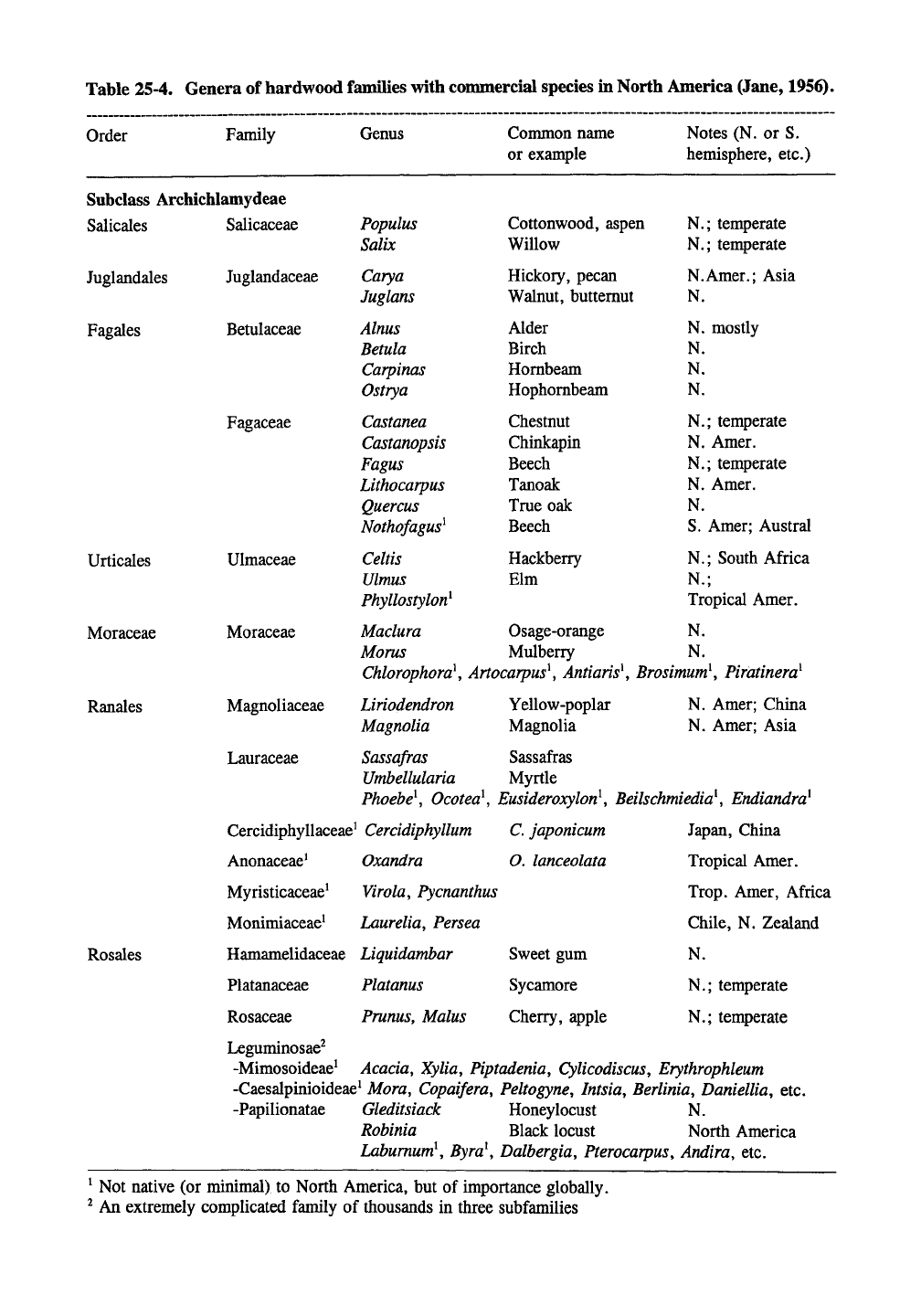

Softwoods are divided into seven botanical

families. Four of these each contain commercial

species important in the U.S. Table 25-3 shows

the genera in each of these families that contain

commercial species.

Angiospermae are arranged into two groups:

conmionly referred to as monocots (monocotyle-

dons) and dicots (dicotyledons). Mono-

cotyledoneae have one leaf in the seed and include

mostly herbaceous plants such

as

grasses and corn.

Fig. 25-2. U.S. forest vegetation. Reprinted from USDA Handbook No. 72 (1955), p. 10.

520 25. WOOD AND FIBER-GROWTH AND ANATOMY

Kingdom:

Phylum:

Sub-Phylum:

Class:

Sub-Class:

Order:

Sub-Order:

Family:

Genus:

Species:

Fig. 25-3.

PLANTS

SPERMAPHYTA

GYMNOSPERMAE

CONIFERALES

PINACEAE

PINUS

STROBUS L.

PLANTS

SPERMAPHYTA

ANGIOSPERMAE

DICOTYLEDONEAE

SYMPETALAE

CONTORTAE

OLEINEAE

OLEACEAE

FRAXINUS

AMERICANA L.

The full classification of a softwood

and a hardwood.

A few woody plants such as bamboo, palm, and

other "nonwood" fiber sources used in pulp and

paper are members of this class.

Dicotyledoneae have two leaves in the seed

and include peanuts, string beans, and many other

plants including the hardwoods. The numerous

Dicotyledoneae are further divided into subclasses,

orders, suborder, families, and some subfamilies.

The anatomy of monocot and dicot stems will be

considered in Chapter 29 along with pulping on

nonwood fibers.

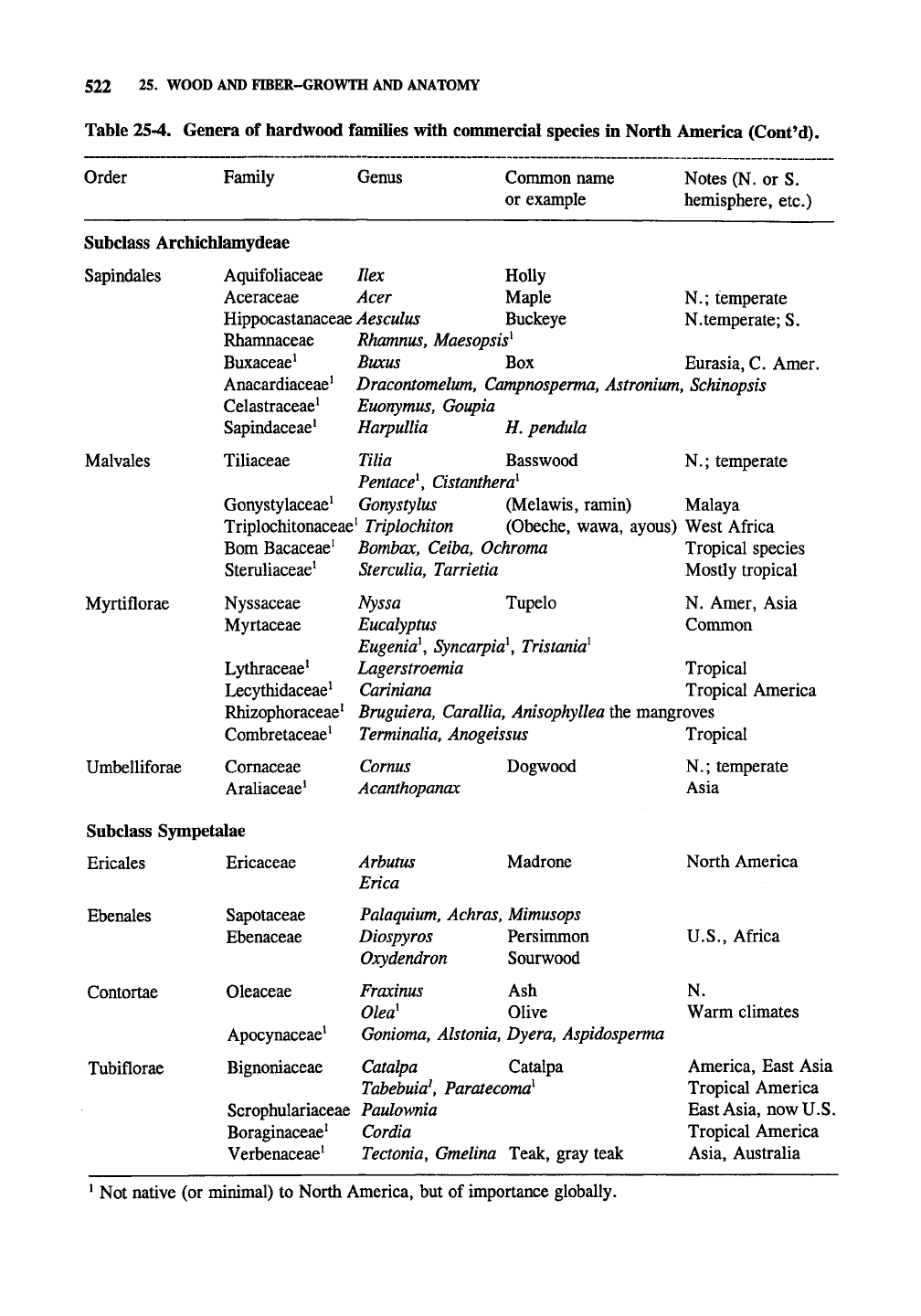

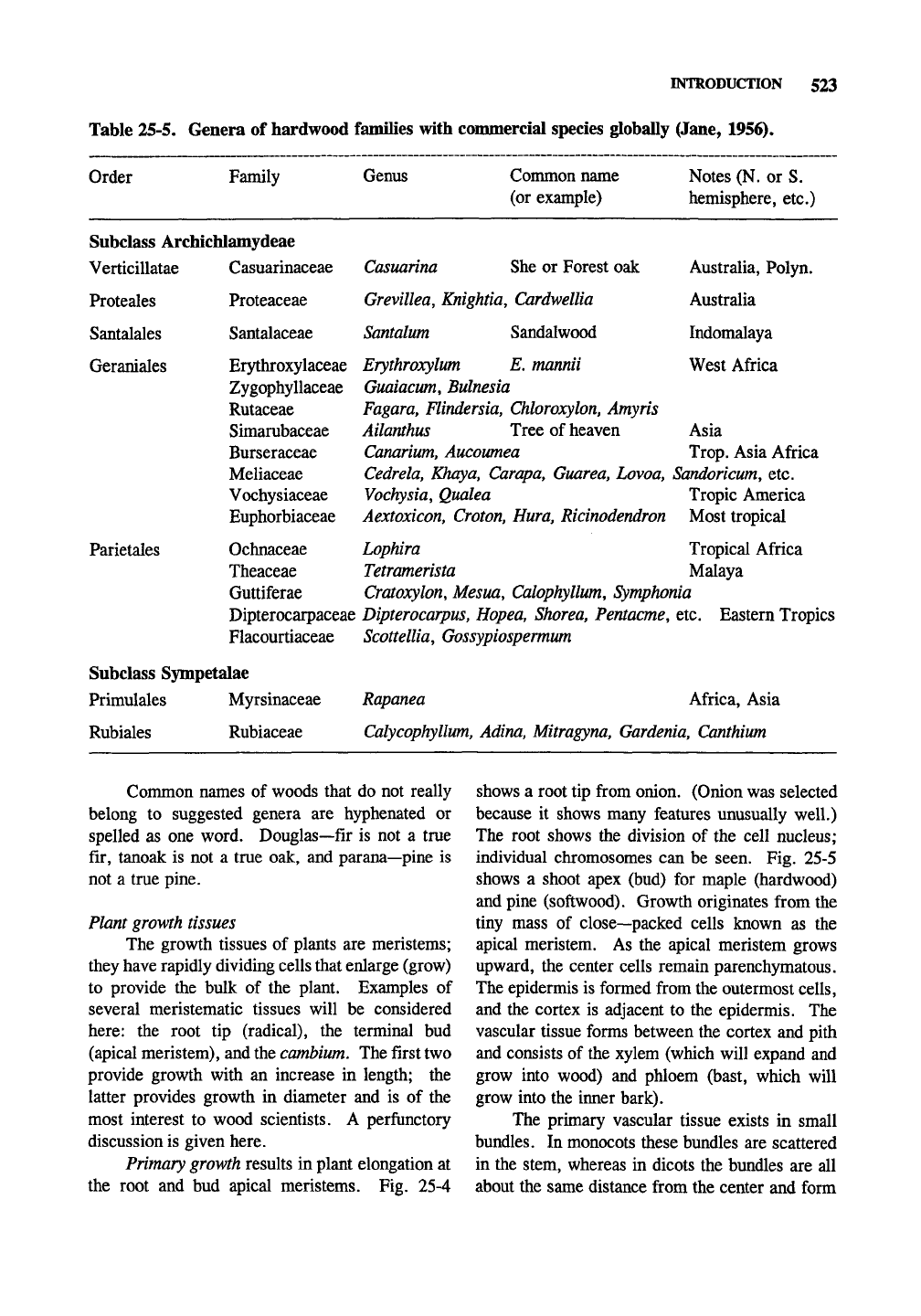

Hardwoods are divided into scores and scores

of families. A relatively few contain all of the

species used for papermaking in the U.S. Table

25-4 shows the genera for some of the major

families of the U.S. with commercial species and

Table 25-5 lists several genera with commercial

species of global importance.

Table 25-3. Genera of softwood families with commercial species in North America.

Family

Pinaceae

Cupressaceae

Taxodiaceae

Taxaceae

Genus

Pinus

Pseudotsuga

Picea

Abies

Larix

Tsuga

Cedrus^

Chamaecyparis

Juniperous

Libocedrus

Thuja

Cupressus

Widdringtonia^

Fitzroya}

Taxodium

Sequoia

Cryptomeria^

Taxus

Common name

Pine

Douglas-fir

Spruce

Firs,

true, silver

Larch

Hemlock

True cedars

False cypress

Juniper, pencil cedar

Incense-cedar

Cedar

True cypresses

Swamp cypresses

Sequoia, Redwood

Yew

Notes (N. or S. hemisphere)

N.

North America, Eastern Asia

N.;

temperate

N.;

temperate

N.

N.;

Eastern Asia

North Africa, Asia Minor

North America; East Asia

N.

North America

North America; Eastern Asia

N.

South and East Africa

Also Callitris\

Tetraclinis^

Western North America

Eastern Asia

N.;

temperate

Other genera of global importance (are not native to North America)

Podocarpaceae

Araucariaceae

Dacrydium

Podocarpus

Araucaria

Agathis

Podocarp

Kauris

S.; temperate, esp. New Zealand

S.; esp New Zealand

S.; not Africa; also Phyllocladus

S.; Southeast Asia, Australasia

^

Not native to North America, but an important genus globally.

Table 25-4. Genera of hardwood families with commercial species in North America (Jane, 1956).

Order

Family

Subclass Archichlamydeae

Salicales

Juglandales

Fagales

Urticales

Moraceae

Ranales

Salicaceae

Juglandaceae

Betulaceae

Fagaceae

Ulmaceae

Moraceae

Magnoliaceae

Lauraceae

Genus

Populus

Salix

Carya

Juglans

Alnus

Betula

Carpinas

Ostrya

Castanea

Castanopsis

Fagus

Lithocarpus

Quercus

Nothofagus^

Celtis

Ulmus

Phyllostylon^

Madura

Moms

Chlorophora\

Liriodendron

Magnolia

Sassafras

Common name

or example

Cottonwood, aspen

Willow

Hickory, pecan

Walnut, butternut

Alder

Birch

Hornbeam

Hophombeam

Chestnut

Chinkapin

Beech

Tanoak

True oak

Beech

Hackberry

Elm

Notes (N. or S.

hemisphere, etc.)

N.;

temperate

N.;

temperate

N.Amer.; Asia

N.

N.

mostly

N.

N.

N.

N.;

temperate

N.

Amer.

N.;

temperate

N.

Amer.

N.

S. Amer; Austral

N.;

South Africa

N.;

Tropical Amer.

Osage-orange N.

Mulberry N.

Artocarpus\ Antiaris\ Brosimum\

Piratinera^

Yellow-poplar

Magnolia

Sassafras

N.

Amer; China

N.

Amer; Asia

Umbellularia Myrtle

Phoebe^,

Ocotea^,

Eusideroxylon\ Beilschmiedia\

Endiandra^

Cercidiphyllaceae^

Cercidiphyllum

C.

japonicum

Anonaceae^ Oxandra O. lanceolata

Myristicaceae^ Virola,

Pycnanthus

Monimiaceae^ Laurelia, Persea

Rosales Hamamelidaceae Liquidambar Sweet gum

Platanaceae Platanus Sycamore

Rosaceae Prunus, Malus Cherry, apple

Leguminosae^

-Mimosoideae^ Acacia, Xylia, Piptadenia,

Cylicodiscus,

Erythrophleum

-Caesalpinioideae^ Mora,

Copaifera,

Peltogyne, Intsia,

Berlinia,

Daniellia, etc

-Papilionatae Gleditsiack Honeylocust N.

Robinia Black locust North America

Labumum\ Byra\ Dalbergia,

Pterocarpus,

Andira, etc.

^

Not native (or minimal) to North America, but of importance globally.

^ An extremely complicated family of thousands in three subfamilies

Japan, China

Tropical Amer.

Trop.

Amer, Africa

Chile, N. Zealand

N.

N.;

temperate

N.;

temperate

522 25. WOOD AND FIBER--GROWTH AND ANATOMY

Table 25-4. Genera of hardwood families with commercial species in North America (Cont'd).

Order

Family

Genus

Common name

or example

Notes (N. or S.

hemisphere, etc.)

Subclass Archichlamydeae

Sapindales

Malvales

Myrtiflorae

Umbelliforae

N.;

temperate

N.temperate; S.

Aquifoliaceae Ilex Holly

Aceraceae Acer Maple

Hippocastanaceae Aesculus Buckeye

Rhamnaceae

Rhamnus,

Maesopsis^

Bwcus Box Eurasia, C. Amer.

Dracontomelum,

Campnosperma,

Astronium,

Schinopsis

Euonymus,

Goupia

Harpullia H, pendula

Buxaceae*

Anacardiaceae

Celastraceae^

Sapindaceae^

Tiliaceae

N.;

temperate

Tilia Basswood

Pentace\

Cistanthera}

Gonystylaceae^ Gonystylus (Melawis, ramin) Malaya

Triplochitonaceae^ Triplochiton (Obeche, wawa, ayous) West Africa

Bom Bacaceae^ Bombax, Ceiba, Ochroma Tropical species

Steruliaceae^ Sterculia, Tarrietia Mostly tropical

Nyssaceae

Myrtaceae

Lythraceae^

Lecythidaceae^

Rhizophoraceae^

Combretaceae^

Cornaceae

Araliaceae^

Tupelo

N.

Amer, Asia

Common

Nyssa

Eucalyptus

Eugenia\ Syncarpia\

Tristania}

Lagerstroemia Tropical

Cariniana Tropical America

Bruguiera, Carallia,

Anisophyllea

the mangroves

Terminalia,

Anogeissus

Tropical

Cornus

Acanthopanax

Dogwood

N.;

temperate

Asia

Subclass Sympetalae

Ericales Ericaceae

Ebenales

Contortae

Tubiflorae

Sapotaceae

Ebenaceae

Oleaceae

Apocynaceae^

Bignoniaceae

Arbutus

Erica

Madrone

Palaquium,

Achras,

Mimusops

Diospyros Persimmon

Oxydendron Sourwood

Fraxinus Ash

Olea^ Olive

Gonioma,

Alstonia,

Dyera, Aspidosperma

Catalpa Catalpa

Tabebuia\

Paratecoma^

Scrophulariaceae Paulownia

Boraginaceae^ Cordia

Verbenaceae^ Tectonia, Gmelina Teak, gray teak

North America

U.S.,

Africa

N.

Warm climates

America, East Asia

Tropical America

East Asia, now U.S.

Tropical America

Asia, Australia

^

Not native (or minimal) to North America, but of importance globally.

INTRODUCTION 523

Table 25-5. Genera of hardwood families with commercial species globally (Jane, 1956) •

Order

Family

Genus

Common name

(or example)

Notes (N. or S.

hemisphere, etc.)

Subclass Archichlamydeae

Verticillatae Casuarinaceae

Proteales Proteaceae

Santalales Santalaceae

Geraniales Erythroxylaceae

Zygophyllaceae

Rutaceae

Simarubaceae

Burseraceae

Meliaceae

Vochysiaceae

Euphorbiaceae

Parietales Ochnaceae

Theaceae

Guttiferae

Dipterocarpaceae

Flacourtiaceae

Subclass Sympetalae

Primulales Myrsinaceae

Rubiales Rubiaceae

Casuarina She or Forest oak Australia, Polyn.

Grevillea,

Knightia,

Cardwellia Australia

Santalum

Sandalwood

Erythroxylum E,

mannii

Guaiacum,

Bulnesia

Fagara,

Flindersia,

Chloroxylon,

Amyris

Ailanthus Tree of heaven

Canarium,

Aucownea

Cedrela, Khaya, Carapa,

Guarea,

Lovoa,

Vochysia,

Qualea

Aextoxicon,

Croton,

Hura,

Ricinodendron

Indomalaya

West Africa

Asia

Trop.

Asia Africa

Sandoricum,

etc.

Tropic America

Most tropical

Lophira Tropical Africa

Tetramerista Malaya

Cratoxylon,

Mesua,

Calophyllum,

Symphonia

Dipterocarpus, Hopea,

Shorea,

Pentacme, etc. Eastern Tropics

Scottellia,

Gossypiospermum

Rapanea Africa, Asia

Calycophyllum,

Adina,

Mitragyna,

Gardenia, Canthiwn

Common names of woods that do not really

belong to suggested genera are hyphenated or

spelled as one word. Douglas—fir is not a true

fir, tanoak is not a true oak, and parana—pine is

not a true pine.

Plant

growth

tissues

The growth tissues of plants are meristems;

they have rapidly dividing cells that enlarge (grow)

to provide the bulk of the plant. Examples of

several meristematic tissues will be considered

here:

the root tip (radical), the terminal bud

(apical meristem), and the

cambium.

The first two

provide growth with an increase in length; the

latter provides growth in diameter and is of the

most interest to wood scientists. A perfunctory

discussion is given here.

Primary growth results in plant elongation at

the root and bud apical meristems. Fig. 25-4

shows a root tip from onion. (Onion was selected

because it shows many features unusually well.)

The root shows the division of the cell nucleus;

individual chromosomes can be seen. Fig. 25-5

shows a shoot apex (bud) for maple (hardwood)

and pine (softwood). Growth originates from the

tiny mass of close—packed cells known as the

apical meristem. As the apical meristem grows

upward, the center cells remain parenchymatous.

The epidermis is formed from the outermost cells,

and the cortex is adjacent to the epidermis. The

vascular tissue forms between the cortex and pith

and consists of the xylem (which will expand and

grow into wood) and phloem (bast, which will

grow into the inner bark).

The primary vascular tissue exists in small

bundles. In monocots these bundles are scattered

in the stem, whereas in dicots the bundles are all

about the same distance from the center and form