Caballero B. (ed.) Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Technology and Nutrition. Ten-Volume Set

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

infects cattle, and S. suihominis from pigs cause human

infections if beef and pork have been undercooked.

Even though domesticated or wild cats are hosts to

Toxoplasma gondii this organism can cause foodborne

infections in humans through consumption of under-

cooked pork or mutton.

0041 Prokaryotic cyanobacteria and blue–green algae are

microorganisms, as are the benthic and the planktonic

algae. These are used as food and are very expensive in

restaurants in different parts of the world. However,

some of these can produce very toxic compounds that

may be transported to mussels, clams, and small herb-

ivorous fish. Shellfish are not harmed or affected by

these high levels of toxins, but a number of distinct

illnesses from these sources are now recognized as

a result. The illnesses they cause include paralytic

shellfish poisoning, neurotoxic shellfish poisoning,

diarrheal shellfish poisoning, amnestic shellfish

poisoning, and ciguatera fish poisoning. The dinofla-

gellates Gonyaulax catenella and G. tamarensis (now

Alexandrium) cause paralytic shellfish poisoning.

Some cyanobacteria, including Microcystis, Ana-

baena, and Aphanizomenon, are main constituents

of algal blooms in lakes, ponds, and reservoirs, and

can easily contaminate water drunk by animals and

man. It is worth noting here that protozoa are import-

ant in assisting in the breakdown of organic matter in

ruminant nutrition.

Microorganisms Exploited by Man for

Food

0042 The fact that microorganisms can transform organic

matter was not known until the middle of the nine-

teenth century. However, man had used certain mi-

crobial metabolic processes, since prehistoric times,

for the preparation of food and drink, e.g., in the

production of beers and wine, the leavening of

bread, and the manufacture of vinegar, cheese, butter,

and, more recently, yogurt. The advent of microbiol-

ogy has led to the development of entirely new indus-

tries based on the use of microorganisms not

previously exploited by man. In wine production,

the grapes are pressed, and the mulch yeast, molds,

and bacteria derived from the surface of the ripe

grapes, including the so-called true wine yeast,

Saccharomyces cerevisiae var. ellipsoids, start the

fermentation process.

0043The soil has a rich reservoir of microorganisms,

and many of these microbial strains have been ex-

ploited for use in industrial production of enzymes,

amino acids, antibiotics, enzymes, and vitamins that

are used in the food industry.

0044Modern yogurt processing involves inoculating

milk with Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactoba-

cillus bulgaricus. For the production of Russian

kefir, milk is inoculated with kefir grain, which is

essentially symbiotically growing Lactobacillus and

yeasts. Indian Idhi (Dosai) used in south India is

essentially fermented by Leuconostoc mesenteroides,

but Streptococcus faecalis is also present and contrib-

utes to its acidic content.

0045In West Africa, the use of naturally fermented

acidic porridges and dough forms the basis of their

staple ‘ethnic foods’. Gari (a fermented and fried

cassava grit) is prepared from an acid-fermented

ground cassava. The principal fermenter is Coryne-

bacterium manihot, which hydrolyzes the starch, pro-

ducing lactic acid and formic acid (evolving heat).

At the optimum fermentation temperature of 35

C,

any cyanide-containing sugars present in the cassava

(Manihot utilissima) are hydrolyzed, removing

the cyanide. As the product becomes more acidic

(around pH 4.25), a yeast-like fungus Geotrichum

candidum (also found in Camembert cheese) de-

velops. Other acid porridges are made from millet

and maize (ogi and koko), maize and wheat

(mahewu), and sorghum. Production of ogi and

mahewu proceeds better at temperatures of about

50

C, which also favors the rapid development of

Lactobacillus delbrueckii.

0046Edible mushrooms and some types of seaweed can

be considered as foods that are themselves microor-

ganisms. Mushrooms are the fruiting bodies of the

fungi and are mainly the stalk surmounted by the cap,

which in reality is a mass of closely packed hyphae.

tbl0003 Table 3 Foodborne pathogenic protozoa

Organism Foodsource Illness

Giardia lamblia Contaminated water, food contaminated by

food-handlers, contaminated vegetables

Giardiasis, nonbacterial diarrhea

Entamoeba histolytica Drinking water and foods Amebiasis

Cryptosporidium parvum Raw milk and sausage, and any food

touched by infected food-handlers

Intestinal, tracheal and pulmonary cryptosporidiosis

Cyclospora cayetanensis,

Acanthamoeba spp.

and Naegleria fowleri

Food, water, fresh fruits and vegetables

(basil, berries, mesclun lettuce)

Cyclosporiasis infection of small intestines,

diarrhea, weight loss, nausea, stomach cramps,

muscle ache, vomiting, fatigue

3884 MICROBIOLOGY/Classification of Microorganisms

0047 Many lactic acid bacteria occur normally in milk

and are responsible for souring. They produce large

amounts of acid, which inhibits the subsequent devel-

opment of other microorganisms. The manufacture

of cheese involves two main steps: curding and

ripening, and this ripening step is carried out by the

action of various bacteria and fungi. Ripening of

the curd is a complex process: Cheddar and ordinary

American cheese is ripened by lactic acid bacteria in

the curd. As these organisms die, proteolytic and fat-

splitting enzymes are released from the cells, slowly

breaking down the milk fat and proteins with the

formation of materials that impart the characteristic

cheese flavor. The so-called mold-ripened cheeses

such as blue cheese and Camembert are produced by

inoculating the curd with special kinds of fungi,

which develop either throughout the curd, as in blue

cheese, or over its surface, as in Camembert. Swiss

cheese is ripened by propionic acid bacteria, which

ferment the lactic acid present in the curd to propi-

onic acid, acetic acid, and carbon dioxide. The ‘holes’

in Swiss cheese are produced by carbon dioxide and

the characteristic flavor by propionic acid.

0048 Butter manufacture is also in part a microbio-

logical process, since the microbial souring of the

cream is desirable for a good subsequent separation

of the butterfat during the churning process. Certain

lactic acid bacteria found on plant materials are re-

sponsible for souring processes that occur in the prep-

aration of pickles. Some lactic acid bacteria belonging

to the genus Leuconostoc produce large amounts

of the extracellular polysaccharide dextran from

sucrose.

0049 In the Far East and Pacific, seaweed has been used

as a source of food for millennia. Seaweed’s diversi-

fied composition makes it far superior to higher

plants nutritionally being rich in polysaccharides,

minerals (especially iodine), and vitamins, and con-

taining 33–35% total fiber. The green alga Ulva

lactuca (sea lettuce) is occasionally used fresh in

salads, and members of the family Fucaceae like

Fucus spp. (also called rockweed or bladderwrack)

and Ascophyllum spp. are used in animal feeds. Rock-

weeds have been used in recipes like clambakes, as

flavorings, and as teas. Laminaria longicruris (oar-

weed or kelp) is a useful source of algin in oriental

markets, sold as ‘kombu’ in health food stores, or

may be cooked as vegetables or added to soup. Lami-

naria digitata is used as a vegetable and as flavoring in

baked beans. Red algae of the Porphyra spp. have

seen various uses as a seasoning, in soups, and as a

constituent of leven bread.

0050 Microorganisms have been used to produce certain

foods, beverages, condiments, and animal feeds, and

recently, several new commercial microbial processes

have been developed. These include the production of

single-cell proteins from microbes to supplement

animal feeds, mushrooms (Agaricus campestris) for

human foods from agricultural wastes (from beet and

cane sugar molasses), microbial rennet for cheese

making, meat-like flavorings using Chinese soy

sauce and Japanese miso processes (employing Asper-

gillus soyae and Aspergillus oryzae) xantha, and some

vitamins. Algae have also been used as a source of

single-cell protein, and the genera Chlorella and Sce-

nedesmus have been grown for food in Japan. Spiru-

lina species have been eaten for many years by the

inhabitants of the northern shores of Lake Chad in

Africa and by the Aztec Indians in Mexico.

See also: Bacillus: Occurrence; Food Poisoning;

Clostridium: Occurrence of Clostridium perfringens;

Detection of Clostridium perfringens; Food Poisoning by

Clostridium perfringens; Occurrence of Clostridium

botulinum; Contamination of Food; Escherichia coli:

Food Poisoning; Food Poisoning by Species other than

Escherichia coli; Food Poisoning: Classification; Listeria:

Listeriosis; Microbiology: Classification of

Microorganisms; Detection of Foodborne Pathogens and

their Toxins; Mycotoxins: Classifications; Salmonella:

Salmonellosis

Further Reading

Adams MR and Moss MO (2000) Food Microbiology.

Cambridge: The Royal Society of Chemistry.

Anonymous (2001) The Bad Bug Book: Foodborne Patho-

genic Microorganisms and Natural Toxins Handbook.

US Food & Drug Administration Center for Food Safety

and Applied Nutrition. College Park, MD, USA: US

Government Printing Office.

Chan EC and McManus EA (1965) Distribution, character-

isation and nutrition of marine microorganisms from the

algae Polysiphonia lanosa and Ascophyllum nodosum.

Canadian Journal of Microbiology 5: 409–420.

Garrity GM (ed.) (2001) Bergey’s Manual of Systematic

Bacteriology. New York: Springer-Verlag.

Lucas JA (1998) Plant Pathology and Plant Pathogens.

Oxford: Blackwell Science.

Microbial Processes: Promising Technologies for Develop-

ing Countries (1979) Washington, DC: National Acad-

emy of Sciences.

Philips CA (1997) Preserving food: a chance in the atmos-

phere. Biologist 44(2): 301–303.

Stanier RY, Doudoroff M and Adelberg EA (1972) General

Microbiology. London: Macmillan.

Stephen J and Pietrowski RA (1981) Bacterial Toxins.

Walton-on-Thames, UK: Thomas Nelson.

Wheeler BEJ (1969) An Introduction to Plant Diseases.

London: John Wiley.

White S and Keleshian M (1994) A Field Guide to Econom-

ically Important Seaweeds of Northern New England.

University of Maine/University of New Hampshire Sea

Grant Marine Advisory Program.

MICROBIOLOGY/Classification of Microorganisms 3885

Detection of Foodborne

Pathogens and their Toxins

J W Austin and F J Pagotto, Bureau of Microbial

Hazards, Ottawa, Canada

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Background

0001 Microbiologists often need to enumerate bacteria in

food samples or determine the presence or absence of

low numbers of specific foodborne pathogens or their

toxins. Detection and quantification of foodborne

pathogens and their toxins are necessary for several

reasons. The most obvious application is for inspec-

tion of consumer foods to determine their quality

and/or safety. Pathogen detection and enumeration

are also necessary for determination of possible

sources of contamination during development of a

Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point plan.

Enumeration of bacteria, or detection of specific

toxins, is necessary for assessing the growth potential

of pathogens in foods.

0002 Traditional techniques have relied upon either

direct detection using microscopy or, more com-

monly, cultural methods that involve growth of

microorganisms in selective and/or differential cul-

ture media. Traditional techniques are still used but

are gradually being replaced by more rapid methods

employing detection of specific antigens (i.e., im-

munoassays) or DNA sequences (i.e., nucleic acid

hybridization or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) ).

These latter methods are very specific and allow

detection of specific pathogens within minutes or

hours, compared with days using traditional cultural

techniques. While these newer methods do not re-

quire microbial growth and allow for more rapid

detection, they typically detect both viable and non-

viable microorganisms. When it is desirable to know

if viable microorganisms are present, a culture

method is preferred.

Direct Detection Using Light Microscopy

0003 Light microscopy allows useful magnifications up to

1000 times and allows examination of food samples

for the presence of bacteria and the morphology of

the contaminants. Direct microscopic counts involve

smearing a known volume of specimen over a defined

area of a microscope slide or counting chamber, fixing

and staining the specimen, and counting bacterial

cells. This method is useful only for samples with at

least 10

6

bacteria per milliliter. The best-known

example of direct microscopic counts is the Breed

smear, which is used to enumerate bacteria in milk.

The numbers of bacterial cells in several fields are

counted and averaged to obtain the count of bacteria

in the original sample.

0004The direct epifluorescent filter technique involves

concentration of microorganisms on membrane

filters to increase the limit of detection, followed by

detection of specific microorganisms using a fluores-

cent label. Depending upon the fluorochrome used,

the technique can be used for several applications.

When stained with acridine orange, for example,

viable cells generally fluoresce orange–red, whereas

nonviable cells fluoresce green. Fluorescently tagged

antibodies specific for bacterial surface antigens can

be used to identify specific bacteria.

Cultural Techniques

0005Cultural techniques usually involve several steps, in-

cluding enrichment for the target organism, isolation

using selective and differential media, and finally

identification of the isolate using phenotypic or geno-

typic analysis. Cultural methods such as the most

probable number (MPN) technique and plate counts

are used to isolate and enumerate microorganisms in

foods.

Enrichment

0006Preenrichment media are designed to increase the

numbers of the target organism, without suppressing

the growth of other organisms. Preenrichment may

allow repair of damaged organisms and encourage

multiplication of the target organism from a few

cells to 10

5

or more per milliliter over a specified

period of time. Selective enrichment media are then

employed to increase the numbers of the target organ-

ism, relative to the other bacteria in the specimen, by

using chemical, physical, or biological methods that

favor the growth or survival, or effect the physical

separation of the target organism. Physical enrich-

ment methods may make use of conditions such as

growth temperature, heat treatment, or size charac-

teristics of specific organisms. Chemical enrichment

methods may employ antibiotics or specific toxic

agents to suppress the growth of unwanted bacteria,

while allowing the growth of the target organism.

Selective agents include antibiotics, dyes, detergents,

and various organic and inorganic chemicals.

Differential Media

0007Once the numbers of the target organism are in-

creased during various enrichment steps, isolation is

attempted using differential plating media, often in-

corporating selective agents. Differential media allow

3886 MICROBIOLOGY/Detection of Foodborne Pathogens and their Toxins

the target microorganism to be distinguished from

other microorganisms based on a recognizable reac-

tion produced by the growth of the target microor-

ganism. There are many media that include pH

indicators to allow for a visual detection of changes

in pH as a result of the metabolic reactions that take

place as the bacteria grow on the media. Commonly

used indicators include bromophenol blue (red in

acid; blue in alkaline), methyl red (red in acid; yellow

in alkaline), bromocresol green (yellow in acid; blue in

alkaline), and phenolphthalein (colorless in acid;

red in alkaline). Bacterial colonies that exhibit the

expected reaction are streaked on nonselective

media to ascertain purity. Pure cultures are then char-

acterized by genotypic or phenotypic methods to

obtain a positive identification.

MPN

0008 The MPN technique involves making replicate dilu-

tions of a sample in an appropriate liquid growth

medium and incubating for growth. The sample is

diluted until aliquots are estimated to contain one

viable cell each. Some aliquots will contain a single

viable cell, whereas others will not contain a viable

cell. Theoretically, a single cell will grow and cause

turbidity or will be recorded via a biochemical reac-

tion giving recognizable changes in the medium. The

tubes showing no growth have presumably not

received a single cell capable of growth. By counting

the number of positive and negative tubes at each

dilution, and referring to statistical tables, the MPN

can be determined. The MPN technique is useful

when the organism cannot be grown on solid

medium, if it is easily overgrown by other bacteria,

or if it produces a unique substance that can be

assayed in broth. An example is determination of

numbers of Clostridium botulinum in a sample by

dilution, followed by detection of botulinum neuro-

toxin in the cultures using the mouse bioassay.

Direct Plate Counts

0009 Direct plating on solid agar media allows isolation of

single clones of bacterial cells, in addition to deter-

mination of numbers of bacteria in a sample. Dilu-

tions of food samples are evenly spread on to solid

growth media and incubated to allow formation of

discrete colonies. Alternatively, dilutions of samples

can be mixed with melted agar and poured into Petri

plates. Such ‘pour plates’ give rise to colonies within

the agar that can be counted to enumerate the bacter-

ial cells in the original sample. As a rule, to obtain

accurate results, the lower number of colonies per

plate is often specified as 20 (lower numbers give

less statistically significant results), whereas the

upper limit is usually 200 colonies per plate (higher

numbers are difficult to count, and colonies may

coalesce).

Physiological Tests

0010The presence of a particular microorganism may be

indicated by detection of a metabolic product or toxin

unique to that organism. Proteolytic strains of

Clostridium botulinum are phenotypically identical

to C. sporogenes, with the exception that the former

produced botulinum neurotoxin. Detection of botuli-

num neurotoxin with the mouse bioassay is an

example of a physiological test to indicate the

presence of a specific microorganism.

Dye Reduction

0011Dye-reduction assays use dyes to estimate the number

of viable cells that are present in certain food prod-

ucts. The most commonly used dyes are methylene

blue and resazurin. Supernatants of food products are

prepared and are added to predetermined solutions of

methylene blue or resazurin. Dye reduction time, in-

versely proportional to the number of cells in the

sample, causes a color change from blue to white

(methylene blue) or slate blue/pink to white (resa-

zurin). In foods that do not contain many inherent

reductive compounds, the dye reduction assay is

comparable with the standard plate count method.

The most common food analyzed is milk.

Bioluminescence

0012Bioluminescence-based methods for the detection of

bacteria can be divided into two: adenosine triphos-

phate (ATP) measurement, and lux gene technology.

Extraction and measurement of bacterial ATP can be

indicative of the number of organisms present in a

sample. The firefly luciferin–luciferase system is the

most commonly used method. In the presence of ATP,

the enzyme luciferase causes light emission, which

can be readily measured using a luminometer. The

amount of light emitted is directly proportional to

the amount of ATP in the sample. Specific inhibitors

are often used to destroy nonbacterial sources of ATP

in food samples. The assay is attractive in determin-

ation of microbial load owing to its rapidity in

obtaining results (usually within 10 min).

0013Some marine bacteria, such as Vibrio fischeri and

V. harveyi, are able to luminesce, and the genes en-

coding this capacity have been characterized. Coding

for the bacterial luciferase, the luxA and luxB genes

have been inserted in species-specific bacteriophages.

The bacteriophages are not metabolically active and

do not emit light. However, when the bacteriophages

attach themselves to their target (for example, a Sal-

monella typhimurium-specific bacteriophage would

only attach itself to S. typhymurium if it were present

MICROBIOLOGY/Detection of Foodborne Pathogens and their Toxins 3887

in the sample), the phage genetic material becomes

inserted into the bacterial cell, where it can replicate

and cause the host cell to luminesce. The reaction

between luciferase and a long-chain aliphatic alde-

hyde substrate (such as dodecanal) provided exogen-

ously in the sample results in the production of light.

Immunoassays

Agglutination

0014 Agglutination reactions involve particulate antigens

capable of binding antibody molecules. Since anti-

body molecules are multivalent, suspended particu-

late antigens form large clumps or aggregates, easily

visible without magnification, when exposed to spe-

cific antibodies. Antibodies that cause this reaction

are referred to as agglutinins. Agglutination assays

can be used to determine concentrations of specific

antibodies in a patient’s immune sera. A constant

amount of a suspended particulate antigen is added

to a series of tubes containing a twofold dilution of

patient’s immune serum, and the titer of antibody in

the serum is the reciprocal of the highest serum dilu-

tion showing agglutination of the particulate antigen.

Agglutination reactions are routinely used for identi-

fication and serotyping of a wide range of bacterial

foodborne pathogens.

Passive Agglutination

0015 Whereas agglutination allows the use of particulate

antigens to determine concentrations of antibodies in

sera, passive Agglutination allows the determination

of the presence and concentration of soluble antigens.

In passive particle (indirect) agglutination, soluble

antigens are coupled to large particles such as eryth-

rocytes or latex spheres. When specific antibodies are

added to coated erythrocytes or latex spheres, anti-

body bridges are formed between the particles, and

agglutination occurs. By addition of a constant

amount of coated particles to various dilutions of

antisera, the titer of antibodies to the antigen used

to coat the particles can be determined.

0016 Alternatively, to determine the concentration of a

soluble antigen, particles can be coated with antibody

specific to the soluble antigen and added to dilutions

of sample containing the soluble antigen. Agglutin-

ation of the antibody-coated particles indicates the

presence of the soluble antigen.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

0017 ELISA uses antibodies linked to enzymes to detect

nanogram to picogram amounts of antigen. ELISAs

rely on the fact that antigens or antibodies can

be bound to a solid support, and antibodies can be

coupled to enzymes without the enzyme losing activ-

ity or the antibody losing binding activity. Enzymes

coupled to antibodies include alkaline phosphatase,

horse-radish peroxidase, and b-galactosidase. Bound

antibody–enzyme conjugates are detected by the for-

mation of a colored reaction product produced by the

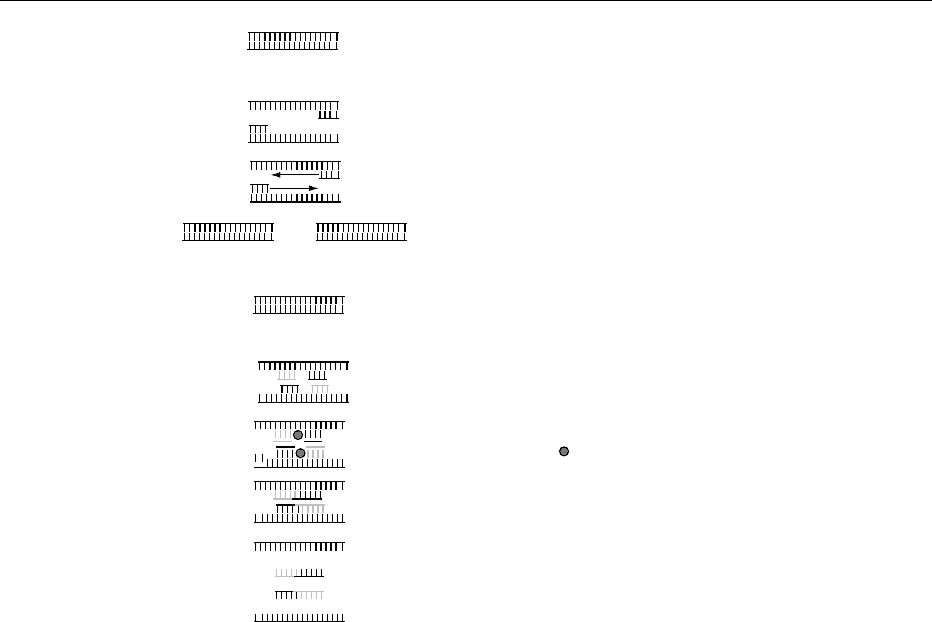

enzyme. Two basic ELISA methods are used: the

double antibody sandwich ELISA (or direct ELISA,

Figure 1), for detection of soluble antigen, and the

indirect immunosorbent ELISA, used for measuring

presence and concentration of antibody in sera.

0018The double antibody sandwich, or direct ELISA,

employs a capture antibody immobilized to a micro-

titer plate. The capture antibody ‘captures’ specific

soluble antigens and immobilizes them on to the

microtiter plate. A reporter antibody binds to the cap-

tured antigen to complete the ‘sandwich.’ This re-

porter antibody is conjugated to an enzyme (e.g.,

alkaline phosphatase or peroxidase), allowing detec-

tion of the reporter antibody. If the specific soluble

antigen is not present, the sandwich of the capture

antibody–antigen–reporter antibody does not form,

and the reporter antibody is not available to produce

a colored reaction product.

Immunofluorescence

0019Antibodies can also be coupled to fluorescent dyes,

allowing detection of bound antibodies by fluores-

cence. Immunofluorescence can be used as a rapid

procedure to detect a specific agent in a specimen

containing a mixture of microorganisms. In the

Sample suspected of containing

antigen of interest (example, a

foodborne pathogen) added

Antibody binds specific antigen

only. Wash away unbound and

unspecific antigens

Add conjugated enzyme-labeled (E)

antibody specific for antigen, wash,

and add substrate for enzyme

Color intensity produced by

enzymatic reaction is proportional

to antigen concentration in sample

Antibodies specific to antigen

bound to solid support

(microtiter plate)

fig0001Figure 1 Direct ELISA assay.

3888 MICROBIOLOGY/Detection of Foodborne Pathogens and their Toxins

direct fluorescent antibody technique, a smear of

the sample is incubated with a solution containing

specific antibody that is directly labeled with a fluor-

escent dye. After allowing the fluorescent antibodies

to bind to the microorganisms, unbound fluorescent

antibodies are removed by washing, and fluorescent

bacteria are observed by epifluorescence light micro-

scopy. The indirect fluorescent antibody technique is

similar, but the smear is first incubated with un-

labeled antibody. Bound antibody is then detected

by incubation with a second fluorescent-labeled

antibody against the immunoglobulin of the animal

species used for the preparation of the initial

antibody.

Immunomagnetic Separation

0020 Immunomagnetic separation involves coupling of

biological macromolecules, such as specific anti-

bodies, to superparamagnetic iron oxide (Fe

3

O

4

) par-

ticles. Superparamagnetic particles exhibit magnetic

properties when placed within a magnetic field but

have no residual magnetism when removed from the

magnetic field. This technology has been incorpor-

ated to make uniform porous polystyrene spheres,

approximately 2–5 mm in diameter, with an even

dispersion of magnetic Fe

3

O

4

throughout the bead.

These magnetic beads are coated with a thin poly-

styrene shell that encases the magnetic material and

provides a defined chemical surface area for the ad-

sorption of coupling of molecules such as antibodies

and streptavidin.

0021 The magnetic particles are added to a heteroge-

neous suspension to bind to the desired target (bac-

terial cells, viruses, proteins, nucleic acids, etc.) and

form a complex composed of the magnetic particle

and target. A magnet is used to immobilize the mag-

netic particles complexed with the target against the

vessel wall, and the remainder of the material is re-

moved. Washing steps to remove food material and

other microorganisms are easily performed while the

particle–target complex is retained. The target then

can be detected using conventional immunoassays,

pipetting or streaking on to agar culture media, or

by using nucleic acid-based methodologies, as the

magnetic particles do not interfere with other

methods of detection.

Nucleic Acid-based Detection and Typing

DNA Probes

0022 Under the proper conditions, a single-stranded DNA

molecule will hybridize selectively with a complemen-

tary sequence of DNA, forming double-stranded

DNA. If the reformed double helix is composed of

DNA strands from different sources it is referred to as

a ‘hybrid.’ The use of a labeled single-stranded DNA

molecule (i.e., a DNA probe) allows detection of

specific, complementary, nucleic acid sequences.

DNA probes can be designed at varying levels of

specificity to detect to species level, or beyond species

level to particular pathogenic strains. Hybridization

is a very specific method and has been used to detect

several specific foodborne pathogens.

0023For hybridization to occur between a DNA probe

and the target sequence, the double-stranded target

DNA must be denatured into two separate strands by

an increase in temperature. When the temperature is

lowered, the strands will reform a double helix if

strands contain similar sequences. The temperature

and salt concentration used for hybridization are crit-

ical. If the temperature is too low, hybrids can be

formed by strands that are not exactly complemen-

tary (low stringency). If the temperature is too high,

strands that are exactly complementary may not hy-

bridize, resulting in a negative reaction. The salt con-

centration is also adjusted to increase or decrease the

stringency of the hybridization. Together, tempera-

ture and salt concentrations are used to optimize the

hybridization conditions so that only the probe and a

filter-bound nucleic acid that is highly homologous to

that probe will bind to each other.

PCR and Other Amplification-based Methods

0024PCR (Figure 2a) is used for in vitro amplification of

specific sequences of DNA. Specific sequences can be

detected by amplification up to several million times.

The amplified DNA can be visualized by electrophor-

esis on an agarose gel, followed by staining with

ethidium bromide. The PCR reaction requires two

oligonucleotide primers, complementary to sequences

on opposite DNA strands. The two strands of the

target DNA are separated by an increase in tempera-

ture (94

C), and the primers are allowed to anneal to

the complementary sequences in the denatured target

DNA at a reduced temperature (50–70

C). A ther-

mally stable DNA polymerase from the thermophilic

bacterium Thermus aquaticus (Taq polymerase, al-

though other polymerases may be used) is used to

synthesize the second strands. Two double-stranded

DNA molecules have now been created from a single

double-stranded molecule. The process is repeated,

with each amplification step doubling the number of

strands of target DNA.

0025Immuno-PCR combines the powerful amplifica-

tion of PCR with antibodies to detect specifically

low levels of antigens. This method is similar to

an ELISA, but the reporter antibody is linked to a

DNA fragment that can be amplified by PCR.

Immuno-PCR has been shown to be 10

2

–10

5

-fold

MICROBIOLOGY/Detection of Foodborne Pathogens and their Toxins 3889

more sensitive than standard ELISA methods and has

been used to detect antigens such as hormones, tumor

markers, botulinum neurotoxin, and viral antigens.

0026 Several techniques that employ PCR-based DNA

fingerprinting of microorganisms have been de-

veloped in the last decade. PCR-based DNA finger-

printing is based on binding of primers to regions of

DNA followed by the generation of species or strain-

specific PCR amplification products. Randomly amp-

lified polymorphic DNA assay (RAPD), also referred

to as arbitrarily primed PCR, employs a single short

(typically 10 base pairs) primer that is not targeted

to any specific bacterial DNA sequence. At low

annealing temperatures, the primer hybridizes at

multiple random chromosomal locations and initiates

DNA synthesis. Owing to its arbitrary nature, RAPD-

PCR is susceptible to technical variation which may

cause problems in reproducibility.

0027 The ligase chain reaction (LCR, Figure 2b) uses

two contiguous oligonucleotides that are joined by

DNA ligase upon perfect hybridization to their target.

The ligated probes are then amplified via thermal

cycling with complementary oligonucleotides. LCR

is better suited than PCR for diagnostic purposes,

although there still remain few data comparing the

two techniques in clinical settings. LCR makes use of

known sequences for the sole purpose of detection,

and this aspect makes it attractive for detection of

foodborne pathogens. PCR, however, generates new

DNA or RNA molecules that may require further

verification or characterization (such as RFLP or

direct sequencing). Although no report exists describ-

ing LCR as a detection system for foodborne patho-

gens, a major advantage would be the high specificity

of the assay. Automation of any amplification-based

method makes such technologies attractive for diag-

nostic laboratories.

0028Nucleic acid sequence-based amplification, or

NASBA, is a technique that amplifies RNA and

DNA targets as antisense, single-stranded RNA by

the concurrent activity of reverse transcriptase,

RNase H, T7 RNA polymerase, and two primers.

NASBA is commonly used to determine HIV load in

clinical samples. However, the technology should be

applicable to food microbiology. Recently, a method

for detection of viable oocysts of Cryptosporidium

parvum in environmental samples using the NASBA

technique was described. Another report described

the use of NASBA to detect Escherichia coli isolates,

which included enterohemorrhagic serotype

Denature to separate strands of DNA

(a)

(b)

Denature to separate strands of DNA

Double stranded DNA template

Double stranded DNA template

Add labeled primers (oligonucleotides) which

hybridize to single stranded target DNA

Two copies of original DNA template made. Each

cycle doubles the amount of specific DNA present

Add primers (oligonucleotides) which hybridize to

single stranded target DNA

Extension of primers by DNA polymerase results in

addition of nucleotides to single stranded template DNA

Ligation via enzymatic sealing of the nick between the

primers by DNA ligase ( )

Two new double stranded DNA targets made

Denature four target strands and repeat. Detect

products based on label used (fluorescence,

enzymatic substrate, etc.)

fig0002 Figure 2 Diagrammatic differences between (a) PCR and (b) LCR. PCR generates a new target via synthesis of new DNA, whereas

LCR joins primers that become the new target DNA molecules.

3890 MICROBIOLOGY/Detection of Foodborne Pathogens and their Toxins

0157:H7. A 140-fg amount of total RNA could be

amplified reproducibly to give a clear, detectable

signal. In addition, a single E. coli cell in a sample

could be detected in less than 14 h.

Pulsed-field Gel Electrophoresis (PFGE)

0029 When bacterial DNA is digested with restriction

enzymes that cut at a small number of sites within

the genome (usually five to 20), high-molecular-

weight fragments of DNA are obtained. These large

fragments of DNA can be separated in a pulsed elec-

tric field, where the direction of the electric field is

alternated between forward and reverse directions,

with the forward pulse being longer in duration

than the reverse pulse. Alternatively, contour-

clamped homogeneous electric field gel electrophor-

esis, where a hexagonal arrangement of six electrodes

are used to generate uniform electric fields at 120

to

each other, can be used to separate DNA molecules as

large as 3 million bases. When the agarose gel is

stained with ethidium bromide, a restriction map

is obtained with the pattern specific to individual

bacterial isolates.

0030 PFGE is highly discriminatory, capable of distin-

guishing between isolates within the same species or

serotype. The major limitations of PFGE include the

requirements for technical skill, sophisticated equip-

ment, and the long duration until completion of the

analysis. Not all strains of bacteria can be typed using

PFGE because of degradation of DNA as a result of

extracellular DNase production or the resistance of

cell walls of some bacteria to lysis. Equally, some

organisms may not yield sufficient discriminatory

information using PFGE.

Ribotyping

0031 Ribotyping makes use of ribosomal RNA gene re-

striction pattern analysis to discriminate between

bacterial isolates. Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) is present

in ribosomes of all bacterial cells and is composed of

molecules of three different sizes: 23S, 16S, and 5S.

The DNA encoding for rRNA is highly conserved

among closely related bacteria, making ribotying

less discriminatory than other DNA-typing proced-

ures. Ribotyping involves isolation of total bacterial

DNA followed by digestion of the DNA with specific

restriction enzymes. The digested DNA is separated

by electrophoresis on an agarose gel and transferred

on to a nylon or nitrocellulose membrane. The DNA

fragments on the membrane are then probed with

labeled DNA fragments complementary to the

rRNA gene sequences. After probing, each fragment

of bacterial DNA containing a ribosomal RNA

gene will be highlighted, creating a fingerprint pat-

tern. An automated ribotyping system is available

from DuPont Qualicon that allows identification of

bacterial isolates, beyond the species level, in ap-

proximately 8 h.

DNA Sequencing

0032Automated DNA sequencing procedures now allow

rapid sequencing of extended DNA sequences. This

has facilitated sequencing of entire genomes, includ-

ing the human genome. Perhaps the ultimate bacterial

identification procedure of the future will be genome

sequencing. Certainly, current technologies allow for

rapid amplification and sequencing of the genes, such

as the 16S rRNA of bacterial isolates. Because 16S

rRNA genes are conserved among isolates of the same

species, yet vary between species, phylogenetic trees

describing their evolutionary relationships have been

described. Indeed, the universal phylogenetic tree de-

scribing the phylogeny of the living world has been

based on 16S or 18S rRNA comparative sequence

analysis.

See also: Clostridium: Occurrence of Clostridium

botulinum; Botulism; Immunoassays: Principles;

Radioimmunoassay and Enzyme Immunoassay;

Microbiology: Classification of Microorganisms;

Microscopy: Light Microscopy and Histochemical

Methods; Nucleic Acids: Properties and Determination;

Physiology; Vibrios: Vibrio cholerae; Vibrio

parahaemolyticus; Vibrio vulnificus

Further Reading

Barbour WM and Tice G (1997) Genetic and immuno-

logic techniques for detecting foodborne pathogens

and toxins. In: Dolye MP, Beuchat LR and Montville

TJ (eds) Food Microbiology. Fundamentals and Fron-

tiers. Washington, DC: American Society for Micro-

biology.

Farber JM (1996) An introduction to the hows and whys

of molecular typing. Journal of Food Protection 59:

1091–1101.

Hill WE and Jinneman KC (2000) Principles and applica-

tions of genetic techniques for detection, identification,

and subtyping of food-associated pathogenic micro-

organisms. In: Lund BM, Baird-Parker TC and Gould

GW (eds) The Microbiological Safety and Quality of

Food. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen.

Holbrook R (2000) Detection of microorganisms in

foods – Principles of culture methods. In: Lund BM,

Baird-Parker TC and Gould GW (eds) The Microbio-

logical Safety and Quality of Food. Gaithersburg, MD:

Aspen.

Koch AL (1981) Growth measurement. In: Gerhardt P,

Murray RGE, Costilow RN et al. (eds) Manual of

Methods for General Bacteriology. Washington, DC:

American Society for Microbiology.

MICROBIOLOGY/Detection of Foodborne Pathogens and their Toxins 3891

Krieg NR (1981) Enrichment and isolation. In: Gerhardt P,

Murray RGE, Costilow RN et al. (eds) Manual of

Methods for General Bacteriology. Washington, DC:

American Society for Microbiology.

Schweitzer B and Kingsmore S (2001) Combining nucleic

acid amplification and detection. Current Opinions in

Biotechnology 12: 21–27.

Sharpe AN (2000) Detection of microorganisms in foods:

Principles of physical methods for separation and asso-

ciated chemical and enzymological methods of detec-

tion. In: Lund BM, Baird-Parker TC and Gould GW

(eds) The Microbiological Safety and Quality of Food.

Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen.

MICROCAPSULES

C Thies, Washington University, St. Louis, MO, USA

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Background

0001 Microencapsulation is the coating of small solid par-

ticles, liquid droplets, or gas bubbles with a thin film

of coating or shell material. Although no officially

approved definition of a microcapsule exists, most

workers use the term microcapsule to describe par-

ticles with diameters between 1 and 1000 mm that

contain a desired ingredient of some sort. Particles

smaller than 1 mm are called nanoparticles; particles

greater than 1000 mm can be called microgranules or

macrocapsules.

0002 Many terms have been used to describe the con-

tents of a microcapsule: active agent, actives, core

material, fill, internal phase, nucleus, and payload.

Many terms have also been used to describe the ma-

terial from which capsules are formed: carrier,

coating, membrane, shell, or wall. For the sake of

consistency, in this article, the material being encap-

sulated is called the core material, and the material

from which the capsule is formed is called the shell

material.

0003 Several reviews discuss the general features of

microencapsulation technology, including encapsula-

tion techniques and applications not discussed here. A

number of authors have reviewed the preparation of

microcapsules that contain food components and the

application of microcapsules to food products.

0004 An understanding of microencapsulation technol-

ogy and the potential contribution that microcapsules

can make to food products rests on a knowledge of

mass transport phenomena, properties of coating ma-

terials, and an understanding of processes by which

small particles are produced. Since the primary pur-

pose of microencapsulation is to control in some

manner mass transport behavior, the shell of a micro-

capsule must control diffusion of material either from

a microcapsule or into a microcapsule (Figure 1). The

shell can provide protection of sensitive food com-

ponents such as flavors, vitamins, or salts from

oxygen, water, light and heat, convert difficult-to-

handle liquids into free-flowing powders readily in-

corporated into various foods or isolate specific food

components during storage.

0005In most cases, food components concentrated

inside microcapsules are released as the food is con-

sumed or during a food preparation step. Release is

achieved by destroying the integrity of the microcap-

sule shell. This is done by dissolving it in water,

melting it, or mechanically rupturing it. There are

cases where no release of core material is desired

until after the food has been ingested and is present

in the digestive system. Perhaps, the intent is for the

core material carried by a microcapsule never to be

released. In these latter situations, the capsule shell

must remain intact throughout the food preparation

and ingestion steps.

0006In order to develop microcapsules with shells that

function as intended, it is essential to understand the

fundamentals of mass transport through shell mater-

ials from which microcapsules are formed, especially

under use conditions. In many cases, the shell is thin,

perhaps having a thickness of a few micrometers or

less. Thus, the morphology or structure of a capsule

shell has a significant impact on microcapsule per-

formance. Overall, capsule morphology also affects

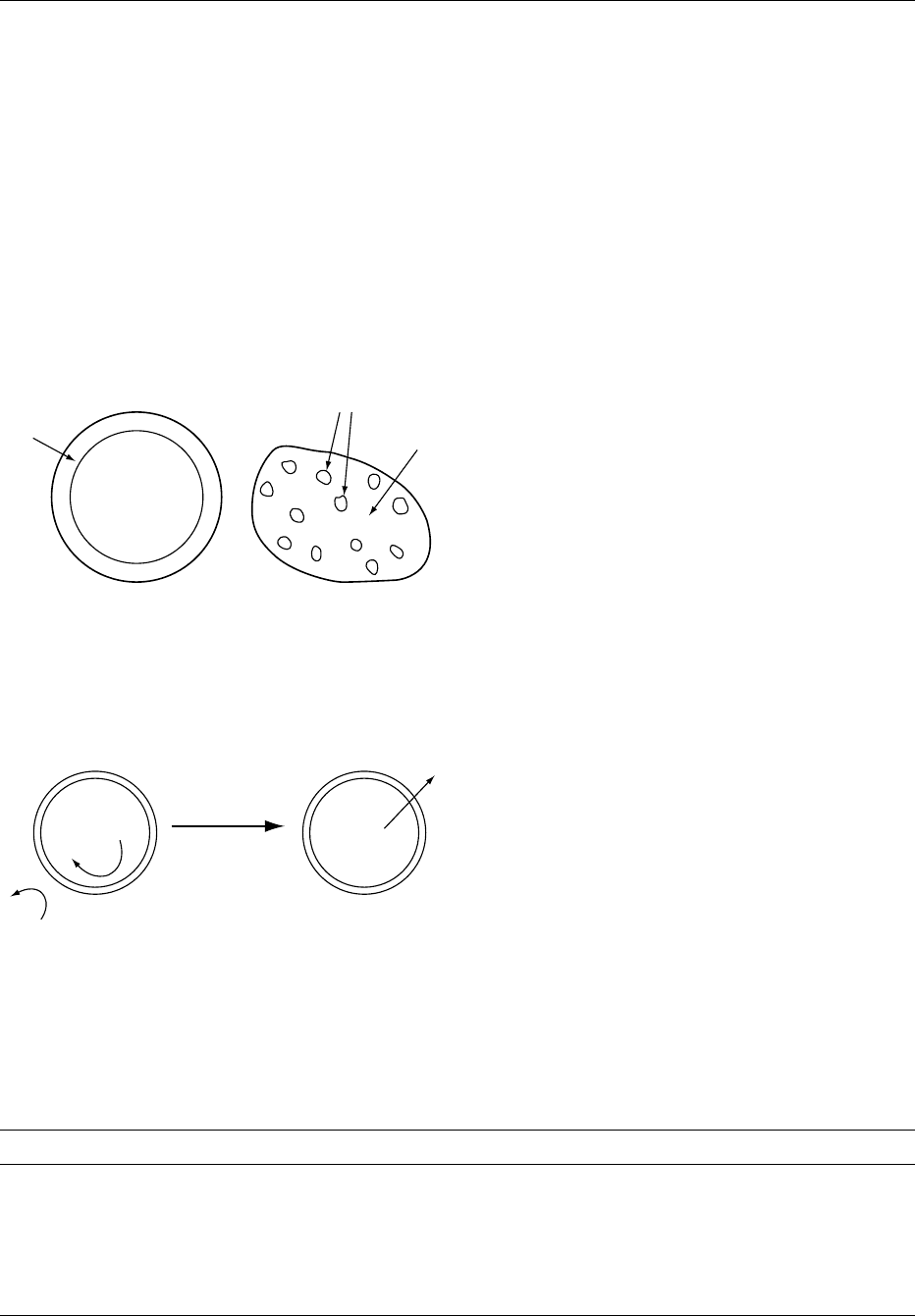

capsule performance. The geometry of a microcap-

sule sample can vary significantly and often is a func-

tion of the process by which the microcapsule was

formed. Figure 2 illustrates two typical capsule struc-

tures, with Figure 2a representing a continuous core/

shell capsule in which a single continuous shell of

uniform thickness surrounds a continuous spherical

region of core material, and Figure 2b representing a

multinuclear capsule in which a number of small

domains of core material are distributed uniformly

throughout a matrix of shell material.

0007During the development of microcapsules for a

specific food application, it is tacitly assumed that a

food-grade microcapsule shell material with suitable

3892 MICROCAPSULES

barrier and fabrication properties is available at an

economically viable price. Proper selection of such

materials requires an appreciation of the properties

of candidate coating materials and requires an under-

standing of materials science. Significantly, few, if

any, candidate capsule shell materials are able to

provide all desired functions economically, so com-

promises must consistently be made when selecting

specific shell materials for a given application.

0008 Table 1 lists representative examples of capsule

shell materials currently used to produce microcap-

sules for commerical food products, and the chemical

class to which the shell material belongs, the encap-

sulation process typically used to produce micro-

capsules with each shell material and frequent

food applications. Although gelatin–gum arabic com-

plex coacervate capsules treated with glutar-

aldehyde are approved for limited consumption of

selected food flavors, they are not approved for

general food use (see Figure 3). Shell material costs

vary greatly. As expected, the food industry favors

the cheapest acceptable shell materials that are

capable of providing desired performance, are avail-

able in commercial quantities, and are approved by

the FDA.

Microencapsulation Processes

General Comments

0009Many microencapsulation processes exist. Some are

based exclusively on physical phenomena. Some util-

ize polymerization reactions to produce a capsule

shell. Others combine physical and chemical phenom-

ena. Because there are so many encapsulation tech-

niques, it is logical to make an effort to attempt to

categorize or classify them in some manner, thereby

providing a means of identifying the concepts on

which various encapsulation technologies are based.

Many authors do this by identifying encapsulation

processes as either chemical or mechanical processes.

This author prefers to classify them as Type A or Type

B processes, since so-called mechanical or physical

processes actually may involve a chemical reaction,

and so-called chemical processes may rely exclusively

on physical phenomena. Table 2 lists representative

examples of Type A and B processes. Type A pro-

cesses are processes in which microcapsules are im-

mersed in a liquid-filled stirred tank or tubular

reactor throughout the encapsulation procedure. In

a Type B process, a gas phase is involved at some stage

of the encapsulation process. Microcapsules are

formed by spraying droplets of coating material on

a core material being encapsulated, solidifying liquid

droplets sprayed or ejected into a gas phase, gel-

ling droplets sprayed or ejected into a liquid bath, or

(a)

Core

material

Shell

material

Core material

Shell

material

(b)

fig0001 Figure 1 Two structures characteristic of many commercial

microcapsules: (a) continuous core/shell structure; (b) multi-

nuclear.

Components

of surrounding

environment:

O

2

, H

2

O, light

Storage Release

Trigger

event

Core Core

fig0002 Figure 2 Ideal storage and release behavior properties de-

sired for many capsules used by the food industry. Courtesy

Thies Technology.

tbl0001 Table 1 Shell materials used to produce commercially significant microcapsules

Shellmaterial Chemical class Encapsulation process Applications

Gum arabic Polysaccharide Spray drying Food flavors

Derivatized starch Polysaccharide Spray drying Food flavors

Gelatin Protein Spray drying Vitamins

Whey protein Protein Spray drying Fats

Maltodextrins Low-molecular-weight carbohydrates Spray drying and desolvation Food flavors

Hydrogenated vegetable oils Glycerides Fluidized bed Assorted food ingredients

Complex coacervation Protein–polysaccharide complex Complex coacervation Assorted flavors

MICROCAPSULES 3893