Cutle, Timothy: On Voice Exchange

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

191

Journal of Music Theory 53:2, Fall 2009

DOI 10.1215/00222909-2010-002 © 2010 by Yale University

On Voice Exchanges

Timothy Cutler

Abstract The voice exchange is an elementary concept that can help solve some of tonal music’s most dif-

ficult analytical problems. Although many essays allude to the subject of voice exchanges, there have been few

direct investigations of the topic. Why such an important compositional technique has remained on the analytical

sidelines can be argued, but what is not debatable is that an understanding of this ubiquitous contrapuntal maneu-

ver is a necessary component of an overall comprehension of tonal music. Featuring examples ranging from

J. S. Bach to Puccini, this essay examines numerous aspects of the voice exchange and its analytical applications,

including (1) the distinction between functional exchanges and pitch swaps that represent little more than optical

illusions, (2) operative voice exchanges that are difficult or impossible to see in the literal score, (3) exchanges that

underscore networks of motivic parallelisms, (4) long-range exchanges employed as persuasive and powerful orga-

nizing tools, (5) surface chromatic “chaos” explained by underlying exchanges, and (6) the relationship between

voice exchanges and a relatively unexplored nuance of tonal analysis—the inverted cadential six-four chord.

the voice exchange is an elementary concept that can help solve some

of tonal music’s most difficult analytical problems.

1

It is well known, for

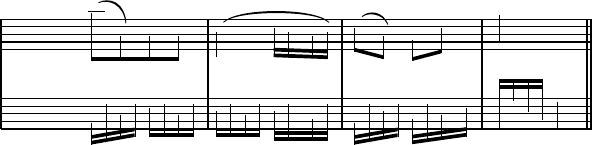

example, that voice exchanges are a common by-product of a harmony’s

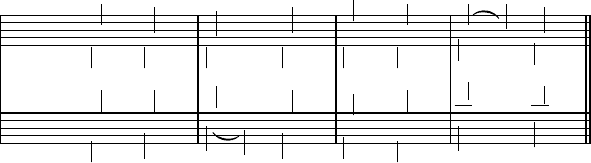

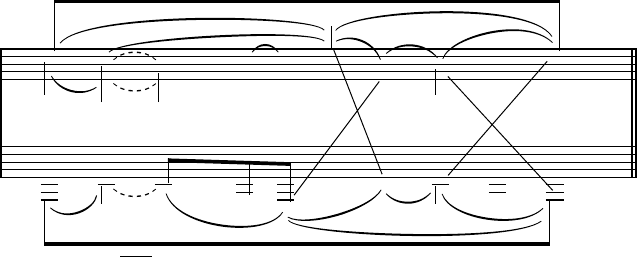

motion from one position to another. Anton Bruckner’s choral work “Tantum

Ergo” no. 4, whose initial motion from root-position to first-inversion tonic

closely resembles the beginning of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata in A≤ major,

op. 110, exemplifies this technique in its most basic form (Example 1). As in

Beethoven’s composition, Bruckner swaps pitches in the outer voices where

they are most audible. And, like Beethoven, Bruckner develops this idea by

unfolding longer exchanges over the entirety of mm. 1–2 as well as from the

second half of m. 2 to the end of m. 3.

2

These latter two examples demon-

strate the voice exchange’s ability to prolong a harmonic entity—in this case

the tonic—when there is intervening material. The interpolative chords are

understood within the context of contrapuntal expansion: The first half of

1 My former teacher William Rothstein used to confound

me by constantly pointing out seemingly random and innoc-

uous voice exchanges. At the time I did not understand the

significance of his observations. Now I do, and this article

is dedicated to him.

2 In the first movement of op. 110, Beethoven features

voice exchanges in each of the opening three measures as

well as a prolonged voice exchange in mm. 5–8. Numer-

ous pieces begin with I–I

6

and a voice exchange, including

J. S. Bach, Chorale no. 169 (Riemenschneider numbering);

Beethoven, Piano Sonata op. 109, mvt. 3, and Violin Sonata

no. 10, op. 96, mvt. 2; Schubert, Impromptu D. 935/3; and

Brahms, “Treue Liebe dauert lange,” op. 33/15.

192

JOUrnAl of MUSIc ThEOrY

m. 2 harmonizes neighboring motions in the tenor and soprano, and the

first half of m. 3 uses a passing chord to support an incomplete neighbor in

the soprano and a neighbor in the tenor—all under the influence of tonic

prolongation.

cutler_01 (code) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/2_cutler Wed May 5 12:09 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 1 of 1 pages

Š

Ý

−

−

−

−

−

−

−

−

‡

‡

ð

ð

ð

ð

\

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

Ł

ð

ð

Ł

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

ð

Ł

Ł

ð

ð

ð

ð

!

Choir

1 Langsam

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Cutler Example 1

Example 1. Bruckner, “Tantum Ergo” no. 4, mm. 1–4

Encountering three instances of voice exchanges within the first three

measures of a piece underscores the notion that this procedure is one of the

most common and important compositional techniques in tonal music. While

numerous authors make passing reference to voice exchanges, there are few

in-depth studies on the topic.

3

As we approach the millennial anniversary of

the voice exchange,

4

I demonstrate that although there is nothing compli-

cated about the fundamental technique itself, its application in various sophis-

ticated musical passages is anything but rudimentary. Specifically, I explore

the following areas: (1) nonfunctional pitch swaps, (2) voice exchanges and

the inverted cadential six-four chord, (3) voice exchanges as motivic indica-

tors, (4) long-range voice exchanges as structural determinants, (5) diatonic

voice exchanges and surface chromaticism, and (6) hidden voice exchanges.

Musical mirages: When a voice exchange isn’t

hunting for voice exchanges can be an addictive pastime, and compositions

offer more examples of analytical fool’s gold than the genuine article. Virtu-

ally all pieces contain hypothetical pitch trades that are irrelevant, dubious,

or nonsensical. For instance, one must navigate through a thicket of conceiv-

able pitch swaps in the second movement of Mozart’s Piano Sonata K. 333.

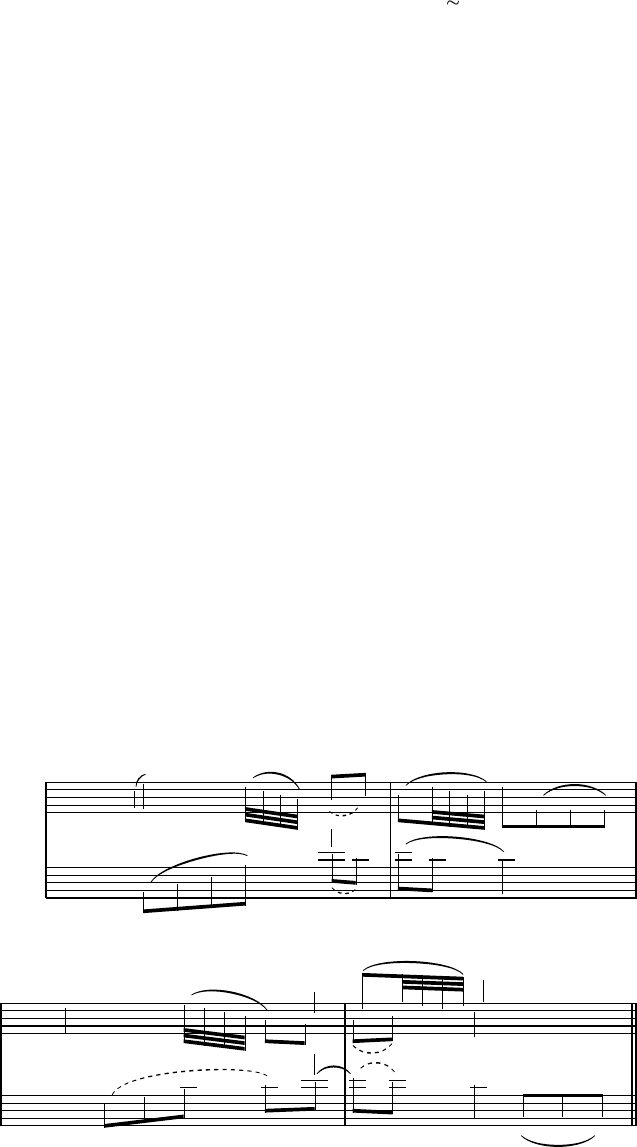

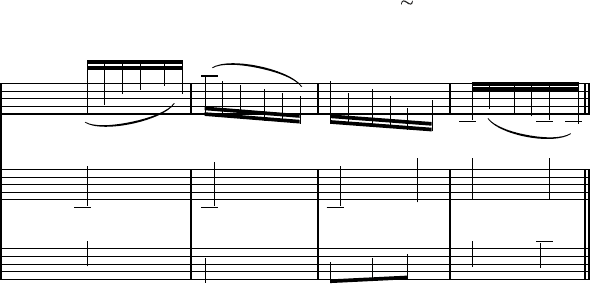

Example 2 posits three interpretations of varying plausibility.

5

Example 2b

3 Among the few essays dealing exclusively with voice

exchanges in common-practice tonality, Parker (1985) traces

the history and seeks a broad definition of the general con-

cept. More recently, Kamien and Wagner (1997) explore a

specific type of voice exchange that was cited previously by

Schenker (1997) and Schachter (1983).

4 According to Parker’s broad definition of voice exchange

(“two or more musical voices exchange the material they

are playing or singing”), this technique has been cited as

far back as the twelfth century (Parker 1985, 31–32). The

remainder of this article refers to the voice exchange in its

more modern theoretical sense.

5 The score is based on the Bärenreiter Urtext of the New

Mozart Edition (New York: Bärenreiter Kassel, 1986).

193

Timothy Cutler On Voice Exchanges

highlights voice exchanges that extend the downbeat harmonies of mm. 14

and 16 as long as possible. however, these pitch swaps are undermined by a

conflict between harmonic rhythm and written meter as well as discrepancies

with the articulation—the left-hand slurring in m. 15 implies that the weak

half of beat 1 functions as a passing element, not as the conclusion of a four-

beat tonic prolongation. Example 2c features voice exchanges that are based

on contour. Even if Mozart’s slurring does not concur fully with this reading,

the resulting harmonic rhythm generates a credible underlying hemiola con-

sisting of tonic and dominant harmonies alternating in multiples of two beats.

This hemiola does not represent the primary metric pattern of the excerpt,

but it does set up a clever interplay with the more straightforward interpre-

tation shown in Example 2d. The principal advantage of this reading is its

simpler harmonic rhythm, with tonic and dominant harmonies changing only

on downbeats. The slurring does not contradict this interpretation, and the

left-hand slur in m. 15 aligns itself with the exchange between the soprano and

tenor. If the final reading is the most direct, and Example 2c shows an added

dimension of metrical nuance, one can categorize Example 2b as an analytical

illusion, a pitch swap that looks plausible on paper but does not resonate with

the musical characteristics of the passage.

One situation that demands restraint transpires when the bass and an

upper voice trade the tonic and dominant scale degrees. This swap may have

little significance when it involves the cadential six-four chord. In the second

movement of Mozart’s Sinfonia concertante K. 364, the outer voices trade

1

ˆ

and 5

ˆ

over a six-measure span (Example 3). Were this to be a functional

cutler_02a (code) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/2_cutler Wed May 5 12:09 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 1 of 1 pages

Ł

�

�

Š

Ý

−

−

−

−

−

−

/

0

/

0

Ł

Ł

ý

\

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł¦

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

�

¦

¹

Ł

l

¼

Ł

l

Ł

l

Š

Ý

−

−

−

−

−

−

¹

Łý

Ł

Ł¦

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

�

�

¦

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

�

�

�

Ł

¹

l

Ł

¼

l

Ł

l

!

!

Piano

14

16

Andante cantabile

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Cutler Example 2a

(a)

Example 2a. Mozart, Piano Sonata K. 333, mvt. 2, mm. 14–17

194

JOUrnAl of MUSIc ThEOrY

cutler_02b (section) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/2_cutler Wed May 5 12:09 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 1 of 1 pages

Š

Ý

−

−

−

−

−

−

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł¦

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

¦

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

¦

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

!

IB

−

:

mm. 14–15

V

6

5

V7

mm. 16–17

I

JMT 53:2 nA-R Job 149-8 Cutler Example 2b

(b)

cutler_02c (section) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/2_cutler Wed May 5 12:09 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 1 of 1 pages

Š

Ý

−

−

−

−

−

−

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł¦

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

¦

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

¦

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

!

IV

6

5

V7 I

(D

(F

F)

D)

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Cutler Example 2c

(c)

cutler_02d (section) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/2_cutler Wed May 5 12:09 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 1 of 1 pages

Š

Ý

−

−

−

−

−

−

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł¦

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

¦

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

¦

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

!

IV

6

5

V7 I

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Cutler Example 2d

(d)

Example 2 (b–d). Mozart, Piano Sonata K. 333, mvt. 2, mm. 14–17

exchange, the downbeats of mm. 116 and 121 would be unified by a com-

mon harmonic element—the tonic. clearly, these two measures do not share

matching functions. Measure 116 expresses stable root-position tonic har-

mony, and m. 121 possesses dominant function in the form of the cadential

six-four. The latter is preceded by predominants, and the c in m. 121 is a

dissonant suspension that requires resolution to the leading tone. Stable 1

ˆ

in

195

Timothy Cutler On Voice Exchanges

cutler_03 (section) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/2_cutler Wed May 5 12:09 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 1 of 1 pages

Š

Ý

−

−

−

−

−

−

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

¦Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

−

−

¦

Ł

Ł

Ł

¦Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

¦

²

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

−

¦

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

−

!

voice exchange?

m. 116 117 118 119 120 121

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Cutler Example 3

Example 3. Mozart, Sinfonia Concertante K. 364, mvt. 2, mm. 116–21

m. 116 has no counterpart in m. 121. This cadential six-four creates a typical

optical illusion: Although two pitches are swapped, no single harmonic entity

is expanded. Therefore, no true voice exchange exists.

This does not imply that two voices cannot trade the tonic and domi-

nant scale degrees in meaningful ways. Brahms composes such an example in

“Meerfahrt,” op. 96/4. heinrich heine’s poem describes two lovers floating

past an enchanted island in a small boat, cast into the endlessly wide sea. The

middle portion of the song is distinguished by a highly chromatic surface

that obscures its diatonic underpinnings (Example 4). After a chromatic voice

exchange connects the opening tonic to the minor dominant in mm. 15–23,

Brahms unfolds the major dominant through upper-voice passing motions

and bass arpeggiation. As the lovers draw nearer to the island from which the

sounds of music grow louder, Brahms pushes the upper line to F in m. 48,

past the more expected E (which would unfold an ascending perfect fourth,

one of the song’s primary motives). The lovers realize that they themselves

are floating past their desired destination, the island, and instead will drift

into the broad sea. It is here in m. 48 that Brahms employs a VII

7

harmony

to initiate a four-measure voice exchange between bass G≥ and upper voice F.

The exchange leads to a VII

4

2

harmony in m. 52 and its resolution to a con-

sonant I

6

4

in the next measure. In order to resolve registrally the prominent

outer voices of the VII

7

(motion to I

6

4

sounds more like inner-voice activity),

Brahms utilizes an operative voice exchange linking I

6

4

and I

5

3

in mm. 53–54.

In this way, bass G≥ in m. 44 eventually ascends to A, and soprano F in m. 48

ultimately descends to E. The fifth of the root-position tonic is implied in

m. 54; it is temporarily displaced by a sixth before it returns in the following

measure. Measures 53–54 contain a legitimate, albeit rare, exchange between

1

ˆ

and 5

ˆ

in the outer voices, unfolding tonic harmony from second inversion

to root position.

6

6 The upper voice in Example 4 outlines an E–F–E neigh-

boring idea spanning mm. 15–54. This expansive gesture

originates from the beginning of the song, where Brahms

highlights E–F≥–E in mm. 2–4 and E–FΩ–E in mm. 14–16.

Likewise, the bassline in mm. 52–54 (F–E–C–A) echoes the

vocal melody in mm. 15–16.

196

JOUrnAl of MUSIc ThEOrY

Metamorphosing meaning: Voice exchanges and the inverted

cadential six-four chord

There is a brief yet noteworthy comment in William rothstein’s “On Implied

Tones” (1991) that went largely unnoticed for fifteen years until rothstein

himself resurrected the thread in “Transformations of cadential Formulae in

the Music of corelli and his Successors” (2006). In the earlier article, roth-

stein examines J. S. Bach’s Sonata in G minor for Unaccompanied Violin,

BWV 1001, as well as accompaniments composed by Schumann and Brahms.

regarding Schumann’s realization of m. 81 in the last movement, rothstein

writes in a footnote, “notice that, in Schumann’s version, the cadential V is

reached by a slide upwards from a 6/3 chord on E-flat. . . . This 6/3, which is

typical of Bach’s own basslines, is best considered an inversion of a cadential

6/4” (1991, 327 n. 50; see Example 5). rothstein’s comment taps into a rela-

tively uncharted theoretical nuance—the cadential six-four chord itself can

appear in inverted form, usually in the guise of a “I

6

” chord.

7

As a result, one

can reconcile passages in which a mechanical calculation of the harmony does

not match its functional implications. rothstein points out that he was not

the first to cite this technique: Schenker comments on the subject in an early

draft of Der Freie Satz.

8

citing compositions by handel, Beethoven, and Brahms,

Schenker writes, “Free composition has sufficient means to compel us to imag-

ine a six-four suspension without needing to present it to us literally; this . . .

leads to many advantages for the voice leading” (rothstein 2006, 268–70).

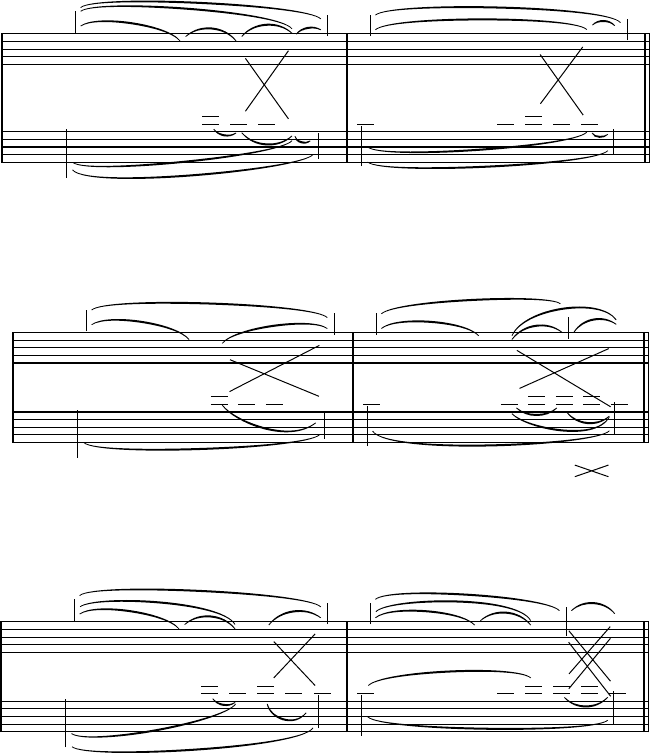

A key feature of inverted cadential six-four chords is the presence,

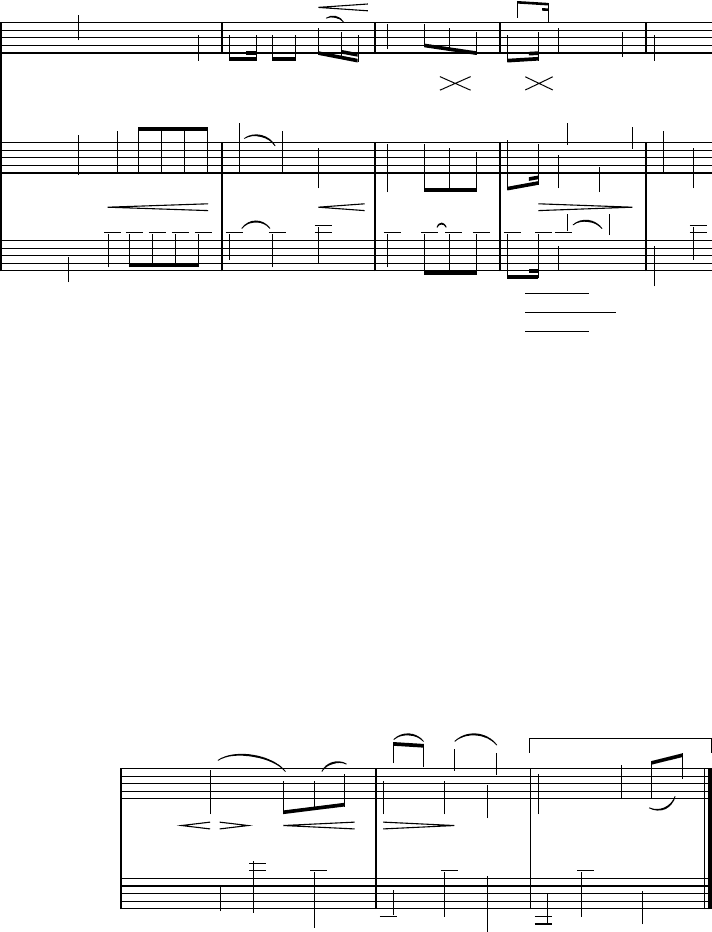

either literal or conceptual, of a voice exchange. The fourth song from Schu-

mann’s Dichterliebe contains an inverted cadential six-four chord with a literal

appearance of a voice exchange (Example 6). After arriving at a half cadence

cutler_04 (section) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/2_cutler Wed May 5 12:09 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 1 of 1 pages

Š

Ý

ð

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

²

Ł²

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

²

²

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

²

²

²Ł

Ł

Ł

�

¦

¦

Ł

Ł²

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł¦

ð

ð

!

()

Ia:

m. 15

V

¦

29

²

40 41 43 44 48 52

I

53

6

4

54

5

3

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Cutler Example 4

Example 4. Brahms, “Meerfahrt,” op. 96/4, mm. 15–54

7 Others who have alluded to inverted cadential six-four

chords include Eric Wen (1999, 287–89) and Allen Cadwal-

lader (1992, 193–94).

8 David Damschroder (2008, 43–45) points out that Heinrich

Christoph Koch made similar comments about these types

of six-four chords in his Handbuch bey dem Studium der

Harmonie (1811).

197

Timothy Cutler On Voice Exchanges

in m. 4, Schumann aims for a perfect authentic cadence four measures later

in the key of the subdominant. In m. 6, the predominant buildup “should”

proceed to a dominant-functioning harmony on the next downbeat. Instead,

one finds an “I

6

” chord. These measures do not, however, represent a plagal

motion from an embellished IV chord to a somewhat stable tonic harmony.

In this excerpt, as well as many others, a voice exchange (as well as the strong

metric location of “I

6

”) guides us to a more accurate harmonic appraisal of the

“I

6

” chord. In m. 7, the exchange of pitches between the outer voices binds

together the visual “I

6

” and actual V

6

4

, fashioning a single harmonic unit. The

“I

6

” tonic label has no meaning here. The downbeat of m. 7 represents an

inverted cadential six-four chord that arrives at its normal and expected posi-

tion through a voice exchange one beat later.

9

Unlike most voice exchanges,

it is the second rather than the first chord that is the primary one.

In this and analogous examples, the inverted cadential six-four has prac-

tical benefits: moving directly to a standard cadential six-four on the downbeat

of m. 7 would create noticeable outer-voice hidden octaves. In some passages,

inverted V

6

4

chords are effective tools for circumventing parallel voice leading.

A traditional V

6

4

in m. 7 of Brahms’s Waltz op. 39/15 would produce parallel

octaves on consecutive downbeats (F–G) and consecutive beats (A≤–G; Exam-

ple 7). In other situations inverted cadential six-four chords are useful for fill-

ing out harmonic texture. Were it not for the inverted form of V

6

4

in Example 8,

the downbeats of mm. 37 and 39 would highlight empty perfect fourths.

10

The voice exchange connecting the inverted and standard versions of

the cadential six-four is often literal. Other times, the exchange is more con-

ceptual, as it is in the Brahms waltz. On the downbeat of m. 7, 3

ˆ

resides in the

Example 5. J. S. Bach (arr. Schumann), Sonata for Unaccompanied Violin BWV 1001, mvt. 4,

mm. 79–82

cutler_05 (section) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/2_cutler Wed May 5 12:10 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 1 of 1 pages

Š

Š

Ý

−

−

−

/

4

/

4

/

4

Ł−

[

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

�

�

−

[

Ł

Ł

¹

¹

Ł

Ł−

¹

¹

Ł

Ł−

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

�

�

−

Ł

Ł

¹

¹

Ł−

Ł

¹

¹

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

�

−

Ł

Ł−

Ł

¹

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

�

¦

[

Ł¦

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

−

[

Ł

Ł−

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

�

�

¦

−

Ł−

!

Violin

Piano

Ic: IV V

6

4

(NOT I

6

)

5

3

I

79 Presto

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Cutler Example 5

9 Another occurrence of II

6

5

–“I

6

” (an inverted cadential

six-four) takes place during a tonicization of G≥ minor in

Chopin’s Etude in E minor, op. 25/5, mm. 57–60. Like Schu-

mann’s excerpt, a literal voice exchange between “I

6

” and

V

6

4

is present in Chopin’s etude. Also see Mozart, String

Quartet K. 421, mvt. 1, mm. 23–24.

10 Mozart’s recomposition of mm. 37–39 is revealing;

while he avoids the empty fourth within the warm con-

fines of F major, Mozart’s traditional cadential six-four in

m. 107 embraces this gloomy sonority in the D-minor

recapitulation.

198

JOUrnAl of MUSIc ThEOrY

bass and 5

ˆ

occurs in the soprano—a reversal of the norm in such contexts.

Although there is no literal voice exchange from the inverted to the tradi-

tional form of the cadential six-four (the latter is not physically present), one

senses that it is implied conceptually.

11

The same is true in the last movement

of Beethoven’s Piano concerto no. 3, op. 37 (Example 9). rothstein writes,

“melody and bass exchange tones on the downbeat of bar 7: The bass B-flat

‘properly’ belongs to the melody, while the melody’s D ‘properly’ belongs to

the bass” (2006, 268). like Example 7, Beethoven’s inverted cadential six-four

averts undesirable parallel octaves in the outer voices (c–D in mm. 6–7).

cutler_06 (section) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/2_cutler Wed May 5 12:10 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 1 of 1 pages

Łý

Ł¦

Š

Š

Ý

²

²

²

/

0

/

0

/

0

Ł

\

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

�

�

\

¾

¾

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

�

�

�

�

¼

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

¹

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

�

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Łý

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

ŁŁ

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

−

Ł

Ł

Ł

ý

¦

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

ý

ý

ý

ý

ý

¦

¦

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

¦

Łý

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

ý

ý

ý

ý

ý

[

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

¦

¦

Łý

ð

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

ý

Ł

Ł

Ł

¦

¦

Ł

�

Ł

�

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

�

�

¾

¾

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

�

�

�

�

!

Voice

Piano

F

A

C:

A

F

II

6

5

G

E

V6

8

4

(NOT I

6

)

E

G

7

3

5I

4

Langsam

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Cutler Example 6

Example 6. Schumann, Dichterliebe, op. 48/4, mm. 4–8

11 Brahms’s sophisticated basslines feature inverted caden-

tial six-four chords with relative frequency. For instance,

inverted V

6

4

chords with conceptual voice exchanges can

be found in “Meerfahrt,” op. 96/4, m. 24; the Concerto for

Violin and Cello op. 102, mvt. 1, m. 427; and Symphony no. 4,

op. 98, mvt. 4, m. 6. For an illustration of an inverted V

6

4

with

a literal voice exchange, see the Violin Sonata no. 2, op. 100,

mvt. 3, m. 11.

cutler_07 (section) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/2_cutler Wed May 5 12:10 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 1 of 1 pages

77777

777777

777777

Š

Ý

−

−

−

−

−

−

−

−

/

0

/

0

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

ý

ý

ý

\

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

l

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

¦

¦

¦

l

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

ý

ý

ý

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

�

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

�

�

!

Piano

IVc: V

6

4

7

I

1.

dolce

6

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Cutler Example 7

Example 7. Brahms, Waltz op. 39/15, mm. 6–8

199

Timothy Cutler On Voice Exchanges

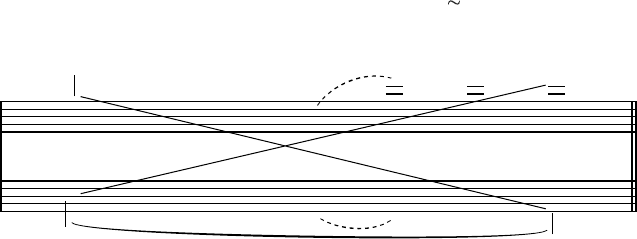

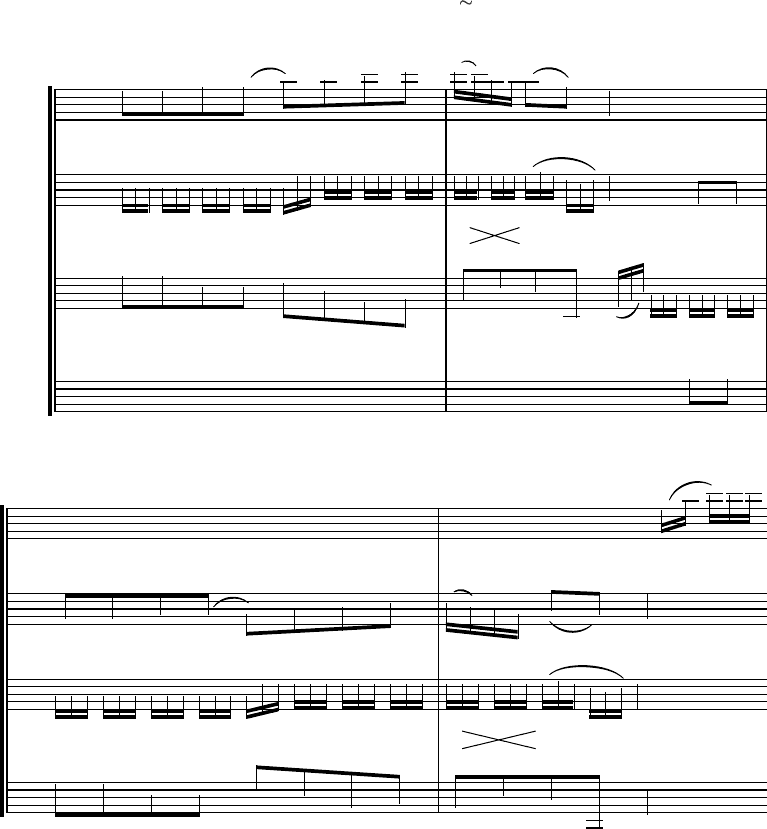

Inverted cadential six-four chords are particularly common in the music

of J. S. Bach. In the first movement of the Violin concerto in A minor, BWV

1041, the harmony prior to m. 145 is unambiguous: First-inversion tonic in

m. 143 is followed by predominant material in m. 144 (Example 10). Due

to harmonic syntax, the growing momentum of the ascending downbeat

bassline, and the strong hypermetrical location of the “I

6

” chord in m. 145,

this downbeat is best understood as an inverted cadential six-four and not a

first-inversion tonic. Within the inverted V

6

4

, 1

ˆ

in the solo violin represents a

dissonant suspension that resolves down by step (with a register transfer) at

cutler_08 (section) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/2_cutler Wed May 5 12:10 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 1 of 1 pages

Š

Š

š

Ý

−

−

−

−

�

�

�

�

Ł

l

\

Ł

\

Ł

l

\

ÿ

ŁŁ

Ł

l

Ł

Ł

l

ŁŁ

Ł

l

Ł

Ł

l

ŁŁ

Ł

Ł

Ł

l

ŁŁ

Ł

Ł

Ł

l

ŁŁ

Ł

l

Ł

Ł

l

ŁŁ

Ł

l

Ł

Ł

l

ŁŁ

Ł

l

Ł

Ł

l

ŁŁ

Ł

Ł

Ł

½

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

l

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

l

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

`

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

�

Ł

¼

Ł

Ł

¹

ŁŁŁ

¼

Ł

l

Ł

Ł

l

\

ŁŁ

Ł

l

Ł

Ł

l

ŁŁ

$

%

Š

Š

š

Ý

−

−

−

−

ÿ

Ł

l

Ł

Ł

l

ŁŁ

Ł

l

Ł

Ł

l

ŁŁ

Ł

l

Ł

Ł

l

ŁŁ

Ł

`

Ł

Ł

l

ŁŁ

Ł

Ł

Ł

l

ŁŁ

Ł

l

Ł

Ł

l

ŁŁ

Ł

l

Ł

Ł

l

ŁŁ

Ł

l

Ł

Ł

l

ŁŁ

½

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

`

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

¾

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

ŁŁ

l

Ł

l

$

%

`

3

Violin I

Violin II

Viola

Cello

F: I6 IV

C

A

V

6

4

A

C

5

3

I

I6 IV

C

A

V

6

4

A

C

5

3

I

36

38

Allegro

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Cutler Example 8

cutler_07 (section) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/2_cutler Wed May 5 12:10 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 1 of 1 pages

77777

777777

777777

Š

Ý

−

−

−

−

−

−

−

−

/

0

/

0

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

ý

ý

ý

\

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

l

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

¦

¦

¦

l

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

ý

ý

ý

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

�

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

�

�

!

Piano

IVc: V

6

4

7

I

1.

dolce

6

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Cutler Example 7

Example 8. Mozart, String Quartet K. 421, mvt. 1, mm. 36–39

200

JOUrnAl of MUSIc ThEOrY

the end of m. 145. Bach’s inverted cadential six-four chord avoids parallel

octaves between the bass (D in m. 144 “should” progress to E on the next

downbeat) and the first violin section. like those in Examples 7 and 9, Bach’s

exchange between inverted and regular forms of the cadential six-four is con-

ceptual because the latter is not literally present.

cutler_09 (section) /home/jobs/journals/jmt/j8/2_cutler Wed May 5 12:10 2010 Rev.2.14 100% By: bonnie Page 1 of 1 pages

Š

Ý

−

−

−

−

−

−

.

0

.

0

Ł

Ł

¦

Ł

Ł

Ł¦

Ł

Ł

Ł

l

Ł

Ł

Ł

l

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł¦

Ł

Ł

Ł

Ł

−

Ł

Ł

Ł−

Ł

Ł

Ł¦

l

Ł

Ł

Ł

l

Ł²

Ł

Ł

�

Ł

Ł

¹

Ł

Ł

¼

�

¹

!

Piano

g: IV V

6

4

5

3

I

5 Allegro

JMT 53:2 A-R Job 149-8 Cutler Example 9

Example 9. Beethoven, Piano Concerto no. 3, op. 37, mvt. 3, mm. 5–8

Within the inverted V

6

4

in m. 145, the bass briefly arpeggiates to 1

ˆ

. Ear-

lier in the movement, there is a less common version of the inverted cadential

six-four chord—a “root-position” inverted cadential six-four, or an apparent

“I

5

3

” harmony. Schenker comments, “The disguise of a six-four suspension

can assume even more drastic forms. Thus, for example, even a root-position

triad, five-three, can under certain circumstances denote nothing other than

a six-four suspension, owing to the progression of the Stufen” (rothstein 2006,

272). Occurrences of “root-position” inverted cadential six-four chords are less

frequent than their six-three counterparts, and conceptual voice exchanges

occur more often than literal ones. Schenker cites “root-position” inverted V

6

4

chords in the first movements of Beethoven’s Piano concerto no. 4, op. 58,

and Brahms’s Piano Quintet op. 34 (rothstein 2006, 272–73). Allen cadwal-

lader refers to this concept in conjunction with the progression I–IV– “I”–V–I.

In some circumstances rhythmic factors suggest that the middle “I

5

3

” is neither

a true root-position tonic nor the upper fifth of the subdominant, but instead

stands for V

6

4

(1992, 197 n. 14).

12

Beginning in m. 102, Bach initiates motion toward an authentic cadence

in D minor (Example 11). As with Example 10, the bassline emphasizes 3

ˆ

in m. 102 and 4

ˆ

in m. 103.

13

In combination with the harmonic progression

(I

6

–II

6

5

), 5

ˆ

“should” appear in the bass on the downbeat of m. 104. Instead, the

bass ascends to the tonic, creating the visual impression of an “I

5

3

” chord. like

some previous examples, bass motion from 4

ˆ

to 1

ˆ

is best explained by voice

leading. In mm. 103–4, the first violins state the theme, including G ascending

to A; this prohibits the same pitches from occurring in the bass due to parallel

12 As shown by Salzer and Schachter (1969, 303), this con-

trapuntal setup occurs in mm. 6–8 of J. S. Bach’s Chorale

no. 217.

13 The weak metric position of the low DΩ’s in mm. 102–3

suggests that they function as arpeggiated offshoots of the

main bass notes, not as a tonic pedal.